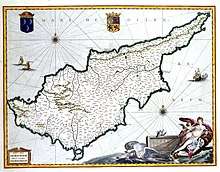

History of the Jews in Cyprus

The history of the Jews in Cyprus dates back at least to the 2nd century BCE, when a considerable community of Jews on the island is first attested.[1] The Jews had close relationships with many of the other religious groups on the island and were seen favourably by the Romans. During the war over the city of Ptolemais between Alexander Jannaeus and Ptolemy IX Lathyros, King of Cyprus, many Jews were killed. During the war the Jewish citizens remained committed in their allegiance to King Lathyros.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Cyprus |

|

|

|

Jewish rebellions and Byzantine rule

The Jews lived well in Cyprus during the Roman rule. During this period, Christianity was preached in Cyprus among the Jews at an early date, St Paul being the first, and the Apostle Barnabas, a native of Cyprus, the second. They attempted to convert the Jews to Christianity. Aristobulus of Britannia The First Bishop of Britain, was the brother of the Apostle Barnabas. Under the leadership of Artemion, the Cypriot Jews participated in the great rebellion against the Romans ruled by Trajan in 117 AD. They sacked Salamis and annihilated the Greek population. According to Dio Cassius, the revolting party massacred 240,000 Cypriot Greeks.[2] According to a late source, written by Eutychius of Alexandria Cypriot Jews attacked Christian monasteries on the island during the reign of Heraclius (610-641).[3]

Twice in 649 and 653, when the population was overwhelmingly Christian, Cyprus was subjected to two raids by Arab forces, which resulted in the capture and abduction into slavery of many Cypriots.[4] One story relates that an enslaved Jew in Syria managed to escape and seek sanctuary on the island, where he converted and settled in Amathus in the late 7th century.[5] Communities of Romaniote Jews from the Byzantine period are known.

Latin Era (1191-1571)

In 1110 CE, Jews were engaged in tax collecting on the island.[3], and Benjamin of Tudela reports that in 1163 there were three distinct Jewish communities in Cyprus, Karaites, Rabbanites and the heretical[6] Epikursin, who observed the Sabbath on Saturday evening.[3] King Peter I enticed Egyptian Jewish traders to come to Cyprus by promising equal treatment for Jews. The Genoese (1373-1463) plundered Jewish property in both Famagusta and Nicosia. In the 16th century, about 2,000 Jews are reported to have been living in Famagusta. When a rumour reached Venice that Joseph Nassi was plotting to betray the Famagusta fortress to the Ottomans, investigations fail to ascertain the veracity of the report, but as a counter-measure the Venetian authorities decided to expel all non-native Jews from the island, leaving the Famagusta community intact.[7]

Ottoman Era (1571-1878)

Cyprus was conquered by the Ottoman Empire after their war with Venice. During Ottoman rule the Jewish community of Cyprus thrived due to the influx of Sephardi Jews from Ottoman lands, who had emigrated en masse to the Ottoman territories after expulsion from Spain in 1492. Famagusta became the main center of the Ottoman Jewish community in Cyprus.

Ottoman rule lasted until 1878, when Cyprus came under British rule.

Modern history

During the last twenty years of the 19th century, several attempts were made to settle Russian and Romanian Jewish refugees in Cyprus. The first attempt, in 1883, was a settlement of several hundred Russians established in Orides near Paphos. In 1885, 27 Romanian families settled on the island as colonists but were not successful in forming communities. Romanian Jews in 1891, again bought land in Cyprus, even though they did not immigrate to the country.[8][9]

Fifteen Russian families under the leadership of Walter Cohen founded a colony in the year 1897 at Margo, with the help of the Ahawat Zion of London and the Jewish Colonisation Association. In 1899, Davis Trietsch, a delegate to the Third Zionist Congress at Basel, in August 1899, attempted to get an endorsement for Jewish colonisation in Cyprus, especially for Romanian Jews. Although, his proposal was refused by the council; Trietsch persisted, convincing two dozen Romanian Jews to immigrate to the land. Twenty-eight Romanian families followed these and received assistance from the Jewish Colonization Association. These settlers established farms at Margo, and at Asheriton. The Jewish Colonisation Association continued to give a small support to the work in Cyprus. Most Jewish communities during the early 1900s (decade) were located in Nicosia. In 1901, the Jewish population of the island was 63 men and 56 women. In 1902, Theodore Herzl presented in a pamphlet to the Parliamentary committee on alien immigration in London, bearing the title "The Problem of Jewish Immigration to England and the United States Solved by Furthering the Jewish Colonisation of Cyprus."

During World War II and the Holocaust, Cyprus played a major role for the Jewish communities of Europe. After the rise of Nazism in 1933, hundreds of Jews escaped to Cyprus. Following the liquidation of the concentration camps of Europe, the British set up a detention camp in Cyprus for Holocaust survivors illegally trying to enter Palestine. From 1946 until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, the British confined 50,000 Jewish refugees on the island. Once the State of Israel was created, most of the refugees moved to Israel. About 2,000 babies were born on the island as they waited to enter Israel.[10]

In 2014 a "Garden of Peace" to commemorate the plight of thousands Jewish refugees imprisoned in British run camps on Cyprus after World War Two was opened in Xylotympou on the east coast of Cyprus.[10]

Today

Israel has had diplomatic relations with Cyprus since Israel's independence in 1948, when Cyprus was a British protectorate. Israel and Cyprus’ associations have continued to expand since 1960, the year of Cyprus’ independence. Despite rankling feelings about side-effects of Turkish-Israel Defense Cooperation, IAF violations of her airspace, and lingering suspicions that Israel had been passing intelligence to Turkey regarding Cyprus's defense systems, Cyprus remained a stalwart friend of Israel throughout the conflicts of recent decades.[11] Today the diplomatic relations between Cyprus and Israel are on a high level reflecting common geopolitical strategies regarding Turkey in particular and economic interests in developing off-shore gas reserves.[12]

Rabbi Arie Zeev Raskin, originally arrived from Israel in Cyprus in 2003 as an emissary of Chabad-Lubavitch. He was sent to the island to help stimulate a Jewish revival.

On September 12, 2005 Rabbi Raskin was formally nominated as the official Rabbi of Cyprus in a ceremony in which guests such as then-Israeli Ambassador, Rabbi Moshe Kotlarsky, Vice Chairman of the Lubavitch educational division at Lubavitch World Headquarters, the Cypriot Education and Culture minister, and Larnaca's deputy mayor Alexis Michaelides. Others included members of the Cypriot government, politicians, diplomats and other prominent members of the local community.

Also in 2005, the Jewish community inaugurated the island's first synagogue, a mikveh (ritual bath), a Jewish cemetery and started a Jewish learning programme in the seaside city of Larnaca.[13] Since 2008, the community oversees the production of a kosher wine, Yayin Kafrisin made of a Cabernet Sauvignon-Grenach Noir blend at the Lambouri winery in Kato Platres, since a Cypriote wine is mentioned in the Torah as a necessary ingredient for the holy incense.[14] As of 2016 the Jewish Community of Cyprus has opened Jewish centers in Larnaca, in Nicosia, in Lemesos and in Ayia Napa offering educational programs for adults, a kindergarten and a Sunday school. The Rabbinate is planning to establish a new larger community center with a museum about the History of the Jews in Cyprus, and a library.[15]

In 2011 Archbishop Chrysostomos II of Cyprus the current leader of the Church of Cyprus signed a declaration that affirms the illegitimacy of the doctrine of collective Jewish guilt for the deicide of Jesus and repudiated the idea as a prejudice 'incompatible with the teaching of the Holy scriptures'.[16]

The Jewish population of Cyprus today (2018) is 3,500.[17]

See also

Bibliography

- Stavros Pantelis, Place of Refuge: A History of the Jews in Cyprus, 2004

- Pieter W. Van der Horst, The Jews of ancient Cyprus in Zutot: Perspectives on Jewish culture Vol. 3, 2004 pp. 110–120

- Gad Freudenthal, Science in medieval Jewish cultures pp. 441-ff. about Cyprus, 2011

- Yitzchak Kerem, "The Jewish and Greek Historical Convivencia in Cyprus; Myth and Reality", Association of European Ideas, Nicosia, Cyprus, 2012

- Benjamin Arbel, "The Jews in Cyprus: New Evidence from the Venetian Period", Jewish Social Studies, 41 (1979), pp. 23–40, reprinted in: Cyprus, the Franks and Venice (Aldershot, 2000).

- Noy, D. et al. Inscriptiones Judaicae Orientis: Vol. III Syria and Cyprus, 2004

- Refenberg, A. A. Das Antike Zyprische Judentum und Seine Beziehungen zu Palästina, Journal of The Palestine Oriental Society, 12 (1932) 209-215

- Nicolaou Konnari, M. and Schabel, C. Cyprus: Society And Culture 1191–1374, pp. 162-ff. 2005

- Falk, A. A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews, p. 315. 1996

- Stillman, N. A. The Jews of Arab Lands, pp. 295-ff. 1979

- Jennings, R. Christians and Muslims in Ottoman Cyprus and the Mediterranean World, 1571–1640, pp. 221-ff. 1993

- Kohen, E. History of the Turkish Jews and Sephardim: Memories of a Past Golden Age, pp. 94–99 on Cyprus. 2007

- Lewis, B. The Jews of Islam, pp. 120-ff. 2014

References

- E. Mary Smallwood, The Jews Under Roman Rule: From Pompey to Diocletian: a Study in Political Relations, BRILL, 2001

- Dio's Rome, Volume 5, Book 68, paragraph 32 'Aspects of the Jewish Revolt in A.D. 115-117,' The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 51, Parts 1 and 2 (1961), pp. 98-104 p.101.

- Alexander Panayotov, 'Jews and Jewish Communities in the Balkans and the Aegean until the twelfth century,' in James K. Aitken, James Carleton Paget (eds.) The Jewish-Greek Tradition in Antiquity and the Byzantine Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2014 pp.54-76 p.74.

- Luca Zavagno Cyprus Between Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages (ca. 600–800): An Island in Transition, Taylor & Francis, 2017 pp.73-79.

- Zavagno pp.84,173.

- Elka Weber Traveling Through Text: Message and Method in Late Medieval Pilgrimage Accounts, Routledge, 2014 p.134

- Benjamin Arbel, Trading Nations: Jews and Venetians in the Early Modern Eastern Mediterranean, BRILL, 1995 pp.62f.

- Yossi Ben-Artzi, 'Jewish rural settlement in Cyprus 1882—1935: a "springboard" or a destiny?,' Jewish History, Vol. 21, No. 3/4 (2007), pp. 361-383

- John M.Shaftesley 'Nineteenth-Century Jewish Colonies in Cyprus,' Transactions & Miscellanies (Jewish Historical Society of England), Vol. 22 (1968-1969), pp. 88-107.

- Nathan Morley,'More than just a footnote to history,' Cyprus Mail 14 August 2016.

- Thomas Diez, The European Union and the Cyprus Conflict: Modern Conflict, Postmodern Union, Manchester University Press 2002 pp.36-39.

- Costas Melakopides, Russia-Cyprus Relations: A Pragmatic Idealist Perspective, Springer 2016 pp.137ff.

- Chabad Lubavitch of Cyprus

- 'First kosher wine from Cyprus,' Jewish Telegraphic Agency 9 April 2008

- Chabad Lubavitch of Cyprus

- 'Cyprus Archbishop meets Chief Rabbi of Israel,' Famagusta Gazette 2011.

- Menelaos Hadjicostis, 'Jewish museum in Cyprus aims to build bridges to Arab world,' Associated Press 6 June 2018.