Gender role

A gender role, also known as a sex role,[1] is a social role encompassing a range of behaviors and attitudes that are generally considered acceptable, appropriate, or desirable for a person based on that person's biological or perceived sex.[2][3] Gender roles are usually centered on conceptions of masculinity and femininity,[2] although there are exceptions and variations. The specifics regarding these gendered expectations may vary substantially among cultures, while other characteristics may be common throughout a range of cultures. There is ongoing debate as to what extent gender roles and their variations are biologically determined, and to what extent they are socially constructed.

Gender roles influence a wide range of human behavior, often including the clothing a person chooses, the profession a person pursues, and the personal relationships a person enters.

Various groups, most notably the feminist movements, have led efforts to change aspects of prevailing gender roles that they believe are oppressive or inaccurate.

The term gender role was first used by John Money and colleagues in 1954, during the course of his study of intersex individuals, to describe the manners in which these individuals expressed that they were male or female even though no clear biological assignment existed.[4]

Background

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines gender roles as "socially constructed roles, behaviors, activities and attributes that a given society considers appropriate for men and women".[5] Debate continues as to what extent gender and gender roles are socially constructed (i.e. non-biologically influenced), and to what extent "socially constructed" may be considered synonymous with "arbitrary" or "malleable".[6][7][8][9][10] Therefore, a concise authoritative definition of gender roles or gender itself is elusive.

In the sociology of gender, the process whereby an individual learns and acquires a gender role in society is termed gender socialization.[11][12][13]

Gender roles are culturally specific, and while most cultures distinguish only two (boy and girl or man and woman), others recognize more. Androgyny, for example, has been proposed as a third gender.[14] An "androgyne" or "androgynous person" is someone with qualities pertaining to both the male and female gender. Other societies have claimed to identify more than five genders,[15][16] and some non-Western societies have three genders: man, woman, and third gender.[17] Some individuals (not necessarily from such a culture) identify with no gender at all.[18]

Many transgender people reject the idea that they constitute a separate third gender, and identify simply as men or women.[19] However, biological differences between (some) trans women and cisgender women have historically been treated as relevant in certain contexts, especially those where biological traits may yield an unfair advantage such as sport.[20]

Gender role is not the same thing as gender identity, which refers to the internal sense of one's own gender, whether or not it aligns with categories offered by societal norms. The point at which these internalized gender identities become externalized into a set of expectations is the genesis of a gender role.[21][22]

Theories of gender as a social construct

According to social constructionism, gendered behavior is mostly due to social conventions. Theories such as evolutionary psychology disagree with that position.

Most children learn to categorize themselves by gender by the age of three.[23] From birth, in the course of gender socialization, children learn gender stereotypes and roles from their parents and environment. Traditionally, boys learn to manipulate their physical and social environment through physical strength or dexterity, while girls learn to present themselves as objects to be viewed.[24] Social constructionists argue that differences between male and female behavior are better attributable to gender-segregated children's activities than to any essential, natural, physiological, or genetic predisposition.[25]

As an aspect of role theory, gender role theory "treats these differing distributions of women and men into roles as the primary origin of sex-differentiated social behavior, [and posits that] their impact on behavior is mediated by psychological and social processes."[26] According to Gilbert Herdt, gender roles arose from correspondent inference, meaning that general labor division was extended to gender roles.[27]

Social constructionists consider gender roles to be hierarchical and patriarchal.[28] The term patriarchy, according to researcher Andrew Cherlin, defines "a social order based on the domination of women by men, especially in agricultural societies".[29]

According to Eagly et al., the consequences of gender roles and stereotypes are sex-typed social behavior because roles and stereotypes are both socially-shared descriptive norms and prescriptive norms.[30]

Judith Butler,[31] in works such as Gender Trouble and Undoing Gender,[32] contends that being female is not "natural" and that it appears natural only through repeated performances of gender; these performances in turn, reproduce and define the traditional categories of sex and/or gender.

Major theorists

Talcott Parsons

Working in the United States in 1955, Talcott Parsons[33] developed a model of the nuclear family, which at that place and time was the prevalent family structure. The model compared a traditional contemporaneous view of gender roles with a more liberal view. The Parsons model was used to contrast and illustrate extreme positions on gender roles. Model A described a total separation of male and female roles, while Model B described the complete dissolution of gender roles.[34]

| Model A – Total role segregation | Model B – Total integration of roles | |

|---|---|---|

| Education | Gender-specific education; high professional qualification is important only for the man | Co-educative schools, same content of classes for girls and boys, same qualification for men and women. |

| Profession | The workplace is not the primary area of women; career and professional advancement is deemed unimportant for women | For women, career is just as important as for men; equal professional opportunities for men and women are necessary. |

| Housework | Housekeeping and child care are the primary functions of the woman; participation of the man in these functions is only partially wanted. | All housework is done by both parties to the marriage in equal shares. |

| Decision making | In case of conflict, man has the last say, for example in choosing the place to live, choice of school for children, buying decisions | Neither partner dominates; solutions do not always follow the principle of finding a concerted decision; status quo is maintained if disagreement occurs. |

| Child care and education | Woman takes care of the largest part of these functions; she educates children and cares for them in every way | Man and woman share these functions equally. |

The model is consciously a simplification; individuals' actual behavior usually lies somewhere between these poles. According to the interactionist approach, gender roles are not fixed but are constantly renegotiated between individuals.[35]

Geert Hofstede

Geert Hofstede, a Dutch researcher and social psychologist who dedicated himself to the study of culture, sees culture as "broad patterns of thinking, feeling and acting" in a society[36] In Hofstede's view, most human cultures can themselves be classified as either masculine or feminine.[37] Masculine culture clearly distinguishes between gender roles, directing men to "be assertive, tough, and focused on material success," and women to "be more modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life."[38] Feminine cultures tolerate overlapping gender roles, and instruct that "both men and women are supposed to be modest, tender, and concerned with the quality of life."[38]

Hofstede's Feminine and Masculine Culture Dimensions states:

Masculine cultures expect men to be assertive, ambitious and competitive, to strive for material success, and to respect whatever is big, strong, and fast. Masculine cultures expect women to serve and care for the non-material quality of life, for children and for the weak. Feminine cultures, on the other hand, define relatively overlapping social roles for the sexes, in which, in particular, men need not be ambitious or competitive but may go for a different quality of life than material success; men may respect whatever is small, weak, and slow.[39]

In feminine cultures, modesty and relationships are important characteristics.[40] This differs from in masculine cultures, where self-enhancement leads to self-esteem. Masculine cultures are individualistic, and feminine cultures are more collective because of the significance of personal relationships.

'The dominant values in a masculine society are achievement and success; the dominant values in a feminine society are caring for others and quality of life'.[41]

John Money

"In the 1950s, John Money and his colleagues took up the study of intersex individuals, who, Money realized, 'would provide invaluable material for the comparative study for bodily form and physiology, rearing, and psychosexual orientation'."[42] "Money and his colleagues used their own studies to state in the extreme what these days seems extraordinary for its complete denial of the notion of natural inclination."[42]

They concluded that gonads, hormones, and chromosomes did not automatically determine a child's gender role.[43] Among the many terms Money coined was gender role, which he defined in a seminal 1955 paper as "all those things that a person says or does to disclose himself or herself as having the status of boy or man, girl or woman."[44]

In recent years, the majority of Money's theories regarding the importance of socialization in the determination of gender have come under intense criticism, especially in connection with the inaccurate reporting of success in the "John/Joan" case, later revealed to be David Reimer.[45][46][47]

Candace West and Don H. Zimmerman

West and Zimmerman developed an interactionist perspective on gender beyond its construction as "roles." For them, gender is "the product of social doings of some sort. undertaken by men and women whose competence as members of society is hostage to its production".[48] They argue that the use of "role" to describe gender expectations conceals the production of gender through everyday activities. Furthermore, roles are situated identities, such as "nurse" and "student," developed as the situation demands, while gender is a master identity with no specific site or organizational context. For them, "conceptualizing gender as a role makes it difficult to assess its influence on other roles and reduces its explanatory usefulness in discussions of power and inequality".[48] West and Zimmerman consider gender an individual production that reflects and constructs interactional and institutional gender expectations.

Biological factors

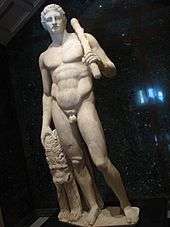

Historically, gender roles have been largely attributed to biological differences in men and women. Although research indicates that biology plays a role in gendered behavior, the extent of its effects on gender roles is less clear.[49][50][51]

One hypothesis attributes differences in gender roles to evolution. The sociobiological view argues that men's fitness is increased by being aggressive, allowing them to compete with other men for access to females, as well as by being sexually promiscuous and trying to father as many children as possible. Women are benefited by bonding with infants and caring for children.[49] Sociobiologists argue that these roles are evolutionary and led to the establishment of traditional gender roles with women in the domestic sphere and men dominant in every other area.[49]

Another hypothesis attributes differences in gender roles to prenatal exposure to hormones. Early research examining the effect of biology on gender roles by John Money and Anke Ehrhardt primarily focused on girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), resulting in higher-than-normal prenatal exposure to androgens. Their research found that girls with CAH exhibited tomboy-like behavior, were less interested in dolls, and were less likely to make-believe as parents.[50][51] A number of methodological problems with the studies have been identified.[52]

Sociologist Linda L. Lindsey critiqued the notion that gender roles are a result of prenatal hormone exposure, saying that while hormones may explain sex differences like sexual orientation and gender identity, they "cannot account for gender differences in other roles such as nurturing, love, and criminal behavior".[49] By contrast, some research indicates that both neurobiological and social risk factors can interact in a way that predisposes one to engaging in criminal behavior (including juvenile delinquency).[53][54]

With regard to gender stereotypes, the societal roles and differences in power between men and women are much more strongly indicated than is a biological component.[55]

Culture

Ideas of appropriate gendered behavior vary among cultures and era, although some aspects receive more widespread attention than others. In the World Values Survey, responders were asked if they thought that wage work should be restricted to only men in the case of shortage in jobs: in Iceland the proportion that agreed with the proposition was 3.6%; while in Egypt it was 94.9%.[56]

Attitudes have also varied historically. For example, in Europe, during the Middle Ages, women were commonly associated with roles related to medicine and healing.[57] Because of the rise of witch-hunts across Europe and the institutionalization of medicine, these roles became exclusively associated with men[57]. In the last few decades these roles have become largely gender-neutral in Western society.[58]

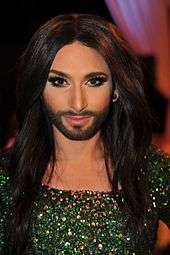

Vern Bullough stated that homosexual communities are generally more tolerant of switching gender roles.[59] For instance, someone with a masculine voice, a five o'clock shadow (or a fuller beard), an Adam's apple, wearing a woman's dress and high heels, carrying a purse would most likely draw ridicule or other unfriendly attention in ordinary social contexts.[60][61][62]

Because the dominant class sees this form of gender expression as unacceptable, inappropriate, or perhaps threatening, these individuals are significantly more likely to experience discrimination and harassment both in their personal lives and from their employers, according to a 2011 report from the Center for American Progress.[63]

Gender roles may be a means through which one expresses one's gender identity, but they may also be employed as a means of exerting social control, and individuals may experience negative social consequences for violating them.[64]

Religion

Different religious and cultural groups within one country may have different norms that they attempt to "police" within their own groups, including gender norms.

Christianity

I Corinthians 11:14 and 15 indicates that long hair is inappropriate for a man but desirable for a woman.

The roles of women in Christianity can vary considerably today (as they have varied historically since the first century New Testament church). This is especially true in marriage and in formal ministry positions within certain Christian denominations, churches, and parachurch organizations.

Many leadership roles in the organized church have been restricted to males. In the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, only men may serve as priests or deacons, and in senior leadership positions such as pope, patriarch, and bishop. Women may serve as abbesses. Most mainstream Protestant denominations are beginning to relax their longstanding constraints on ordaining women to be ministers, though some large groups are tightening their constraints in reaction. Charismatic and Pentecostal churches have embraced the ordination of women since their founding.

Christian traditions that officially recognize "saints", persons of exceptional holiness of life having attained the beatific vision (heaven), include female saints. Most prominent is Mary, mother of Jesus who is highly revered throughout Christianity, particularly in the Catholic and Orthodox churches where she is considered the "Theotokos", i.e. "Mother of God". Women prominent in Christianity have included contemporaries of Jesus, subsequent theologians, abbesses, mystics, doctors of the church, founders of religious orders, military leaders, monarchs and martyrs, evidencing the variety of roles played by women within the life of Christianity. Paul the Apostle held women in high regard and worthy of prominent positions in the church, though he was careful not to encourage disregard for the New Testament household codes, also known as New Testament Domestic Codes or Haustafelen, of Greco-Roman law in the first century.

Islam

According to Dhami and Sheikh, gender roles in Muslim countries are centered on the importance of the family unit, which is viewed as the basis of a balanced and healthy society.[65] Islamic views on gender roles and family are traditionally conservative.

Many Muslim-majority countries, most prominently Saudi Arabia, have interpretations of religious doctrine regarding gender roles embedded in their laws.[66] In the United Arab Emirates, non-Muslim Western women can wear crop tops, whereas Muslim women are expected to dress much more modestly when in public. In some Muslim countries, these differences are sometimes even codified in law.

In some Muslim-majority countries, even non-Muslim women are expected to follow Muslim female gender norms and Islamic law to a certain extent, such as by covering their hair. (Women visiting from other countries sometimes object to this norm and sometimes decide to comply on pragmatic grounds, in the interest of their own safety. For example, in Egypt, women who do not dress "modestly" may be perceived as akin to prostitutes.)

Muhammad described the high status of mothers in both of the major hadith collections (Bukhari and Muslim). One famous account is:

The Qur'an prescribes that the status of a woman should be nearly as high as that of a man.[67] How gender roles are honored is largely cultural. While some cultures encourage men and women to take on the same roles, others promote a more traditional, less dominant role for the women.[68]"A man asked the Prophet: 'Whom should I honor most?' The Prophet replied: 'Your mother'. 'And who comes next?' asked the man. The Prophet replied: 'Your mother'. 'And who comes next?' asked the man. The Prophet replied: 'Your mother!'. 'And who comes next?' asked the man. The Prophet replied: 'Your father'"

Hinduism

Hindu deities are more ambiguously gendered than the deities of other world religions. This informs female and males relations, and informs how the differences between males and females are understood[69]

However, in a religious cosmology like Hinduism, which prominently features female and androgynous deities, some gender transgression is allowed. This group is known as the hijras, and has a long tradition of performing in important rituals, such as the birth of sons and weddings. Despite this allowance for transgression, Hindu cultural traditions portray women in contradictory ways. Women's fertility is given great value, but female sexuality is depicted as potentially dangerous and destructive.[70]

Studies on marriage in the U.S.

The institution of marriage influences gender roles, inequality, and change.[71] In the United States, gender roles are communicated by the media, social interaction, and language. Through these platforms society has influenced individuals to fulfill from a young age the stereotypical gender roles in a heterosexual marriage. Roles traditionally distributed according to biological sex are increasingly negotiated by spouses on an equal footing.

Communication of gender roles in the United States

In the U.S., marriage roles are generally decided based on gender. For approximately the past seven decades, heterosexual marriage roles have been defined for men and women based on society's expectations and the influence of the media.[72] Men and women are typically associated with certain social roles dependent upon the personality traits associated with those roles.[73] Traditionally, the role of the homemaker is associated with a woman and the role of a breadwinner is associated with a male.[73]

In the U.S., single men are outnumbered by single women at a ratio of 100 single women to 86 single men,[74] though never-married men over the age of 15 outnumber women by a 5:4 ratio (33.9% to 27.3%) according to the 2006 U.S. Census American Community Survey. The results are varied between age groups, with 118 single men per 100 single women in their 20s, versus 33 single men to 100 single women over 65.[75]

The numbers also vary between countries. For example, China has many more young men than young women, and this disparity is expected to increase.[76] In regions with recent conflict such as Chechnya, women greatly outnumber men.[77]

In a cross-cultural study by David Buss, men and women were asked to rank the importance of certain traits in a long term partner. Both men and women ranked "kindness" and "intelligence" as the two most important factors. Men valued beauty and youth more highly than women, while women valued financial and social status more highly than men.

Media

In today's society, media saturates nearly every aspect of one's life. It seems inevitable for society to be influenced by the media and what it is portraying.[72] Roles are gendered, meaning that both males and females are viewed and treated differently according to biological sex, and because gendered roles are learned, the media has a direct impact on individuals. Thinking about the way in which couples act on romantic television shows or movies and the way women are portrayed as passive in magazine ads, reveals a lot about how gender roles are viewed in society and in heterosexual marriages.[72] Traditional gendered roles view the man as a “pro-creator, a protector, and a provider,” and the woman as “pretty and polite but not too aggressive, not too outspoken and not too smart.” [78] Media aids in society conforming to these traditional gendered views. People learn through imitation and social-interaction both in the physical world and through the media; television, magazines, advertisements, newspapers, the Internet, etc.[78] Michael Messner argues that "gendered interactions, structure, and cultural meanings are intertwined, in both mutually reinforcing and contradictory ways."[79]

Television's influence on society, specifically the influence of television advertisements, is shown in studies such as that of Jörg Matthes, Michael Prieler, and Karoline Adam. Their study into television advertising has shown that women are much more likely to be shown in a setting in the home compared to men. The study also shows that women are shown much less in work-like settings. This underrepresentation in television advertising is seen in many countries around the world but is very present in developed countries.[80] In another study in the Journal of Social Psychology, many television advertisements in countries around the world are seen targeting women at different times of the day than men. Advertisements for products directed towards female viewers are shown during the day on weekdays, while products for men are shown during weekends. The same article shows that a study on adults and television media has also seen that the more television adults watch, the more likely they are to believe or support the gender roles that are illustrated. The support of the presented gender stereotypes can lead to a negative view of feminism or sexual aggression.[81]

It has been presented in the journal article by Emerald Group Publishing Limited that adolescent girls have been effected by the stereotypical view of women in media. Girls feel pressured and stressed to achieve a particular appearance and there have been highly worrying consequences for the young girls if they fail to achieve this look. These consequences have ranged from anxiety to eating disorders. Young girls in an experiment of this journal article describe pictures on women in advertisements as unrealistic and fake. They are dressed in little and revealing clothing which sexualised the women and expose their thin figures, that are gazed upon by the public, creating an issue with stereotyping in the media.

It has also been presented that children are affected by gender roles in the media. Children's preferences in television characters are most likely to be to characters of the same gender. Because children favor characters of the same gender, the characteristics of the character are also looked to by children.[82] In another journal article by Emerald Group Publishing Limited, the underrepresentation of women in children's television shows between 1930 and 1960 is examined. While studies between 1960 and 1990 show an increase in the representation of women in television, studies conducted between 1990 and 2005, a time when women were considered to be equal to men by some, show no change in the representation of women in children's television shows. Women, being underrepresented in children's television shows, are also often portrayed as married or in a relationship, while men are more likely to be single. This reoccurring theme in relationship status can be reflected in the ideals of children that only see this type of representation.[83]

Social Interaction

Gendered roles in heterosexual marriages are learned through imitation. People learn what society views as appropriate gender behaviors from imitating the repetition of actions by one's role-model or parent of the same biological sex.[78] Imitation in the physical world that impacts one's gendered roles often comes from role-modeling parents, peers, teachers, and other significant figures in one's life. In a marriage, oftentimes each person's gendered roles are determined by his or her parents. If the wife grew up imitating the actions of traditional parents, and the husband non-traditional parents, their views on marital roles would be different.[78] One way people can acquire these stereotypical roles through a reward and punishment system. When a little girl imitates her mother by performing the traditional domestic duties she is often rewarded by being told she is doing a good job. Nontraditionally, if a little boy was performing the same tasks he would more likely be punished due to acting feminine.[78] Because society holds these expected roles for men and women within a marriage, it creates a mold for children to follow.[84]

Changing gender roles in marriage

Over the years, gender roles have continued to change and have a significant impact on the institution of marriage. Gender roles can be defined as the behaviors, values, and attitudes that a society considers appropriate for both male and female.[71] Traditionally, men and women had completely opposing roles, men were seen as the provider for the family and women were seen as the caretakers of both the home and the family.[71] However, in today's society the division of roles are starting to blur. More and more individuals are adapting non-traditional gender roles into their marriages in order to share responsibilities. This revolutionary view on gender roles seeks out equality between sexes. In today's society it is more likely that a husband and wife are both providers for their family. More and more women are entering the workforce while more men are contributing to household duties.[71]

After around the year 1980, divorce rates in the United States stabilized.[85] Scholars in the area of sociology explain that this stabilization was due to several factors including, but not limited to, the shift in gender roles,.The attitude concerning the shift in gender roles can be classified into two perspectives: traditional and egalitarian. Traditional attitudes uphold designated responsibilities for the sexes- wives raise the children and keep the home nice, and men are the breadwinners. Egalitarian attitudes uphold responsibilities being carried out equally by both sexes- wives and husbands are both breadwinners and they both take part in raising the children and keeping the home nice.[86] Over the past 40 years, attitudes in marriages have become more egalitarian.[87] Two studies carried out in the early 2000s have shown strong correlation between egalitarian attitudes and happiness and satisfaction in marriage, which scholars believe lead to stabilization in divorce rates. The results of a 2006 study performed by Gayle Kaufman, a professor of sociology, indicated that those who hold egalitarian attitudes report significantly higher levels of marital happiness than those with more traditional attitudes.[88] Another study executed by Will Marshall in 2008 had results showing that relationships with better quality involve people with more egalitarian beliefs.[89] It has been assumed by Danielle J. Lindemann, a sociologist who studies gender, sexuality, the family, and culture, that the shift in gender roles and egalitarian attitudes have resulted in marriage stability due to tasks being carried out by both partners, such as working late-nights and picking up ill children from school.[90] Although the gap in gender roles still exists, roles have become less gendered and more equal in marriages compared to how they were traditionally.

Changing roles

Throughout history spouses have been charged with certain societal functions.[91] With the rise of the New World came the expected roles that each spouse was to carry out specifically. Husbands were typically working farmers - the providers. Wives typically cared for the home and the children. However, the roles are now changing, and even reversing.[92]

Societies can change such that the gender roles rapidly change. The 21st century has seen a shift in gender roles due to multiple factors such as new family structures, education, media, and several others. A 2003 survey by the Bureau of Labor Statistics indicated that about 1/3 of wives earn more than their husbands.[93]

With the importance of education emphasized nationwide, and the access of college degrees (online, for example), women have begun furthering their educations. Women have also started to get more involved in recreation activities such as sports, which in the past were regarded to be for men.[94] Family structures are changing, and the number of single-mother or single-father households is increasing. Fathers are also becoming more involved with raising their children, instead of the responsibility resting solely with the mother.

According to the Pew Research Center, the number of stay-at-home fathers in the US nearly doubled in the period from 1989 to 2012, from 1.1 million to 2.0 million.[95] This trend appears to be mirrored in a number of countries including the UK, Canada and Sweden.[96][97][98] However, Pew also found that, at least in the US, public opinion in general appears to show a substantial bias toward favoring a mother as a care-taker versus a father, regardless of any shift in actual roles each plays.[99]

Gender equality allows gender roles to become less distinct and according to Donnalyn Pompper, is the reason "men no longer own breadwinning identities and, like women, their bodies are objectified in mass media images."[100] The LGBT rights movement has played a role increasing pro-gay attitudes, which according to Brian McNair, are expressed by many metrosexual men.[101]

Besides North America and Europe, there are other regions whose gender roles are also changing. In Asia, Hong Kong is very close to the USA because the female surgeons in these societies are focused heavily on home life, whereas Japan is focused more on work life. After a female surgeon gives birth in Hong Kong, she wants to cut her work schedule down, but keeps working full time (60-80 hours per week).[102] Similar to Hong Kong, Japanese surgeons still work long hours, but they try to rearrange their schedules so they can be at home more (end up working less than 60 hours)[102]. Although all three places have women working advanced jobs, the female surgeons in the USA and Hong Kong feel more gender equality at home where they have equal, if not more control of their families, and Japanese surgeons feel the men are still in control[102]. A big change was seen in Hong Kong because the wives used to deal with a bad marriage. Now, Chinese wives have been divorcing their husbands when they feel unhappy with their marriages, and are stable financially. This makes the wife seem more in control of her own life, instead of letting her husband control her[103]. Other places, such as Singapore and Taipei are also seeing changes in gender roles. In many societies, but especially Singapore and Taipei, women have more jobs that have a leadership position (ie. A doctor or manager), and fewer jobs as a regular worker (ie. A clerk or salesperson).[103] The males in Singapore also have more leadership roles, but they have more lower level jobs too. In the past, the women would get the lower level jobs, and the men would get all the leadership positions[103]. There is an increase of male unemployment in Singapore, Taipei, and Hong Kong, so the women are having to work more in order to support their families[103]. In the past, the males were usually the ones supporting the family. In India, the women are married young, and are expected to run the household, even if they did not finish school[104]. It is seen as shameful if a woman has to work outside of the house in order to help support the family[104]. Many women are starting jewelry businesses inside their houses and have their own bank accounts because of it. Middle aged women are now able to work without being shameful because they are no longer child bearing.[104]

Gender stereotype differences in cultures: East and West

According to Professor Lei Chang, gender attitudes within the domains of work and domestic roles, can be measured using a cross-cultural gender role attitudes test. Psychological processes of the East have historically been analysed using Western models (or instruments) that have been translated, which potentially, is a more far-reaching process than linguistic translation. Some North American instruments for assessing gender role attitudes include:

- Attitudes Towards Women Scale,

- Sex-Role Egalitarian Scale, and

- Sex-Role Ideology Scale.

Through such tests, it is known that American southerners exhibit less egalitarian gender views than their northern counterparts, demonstrating that gender views are inevitably affected by an individual's culture. This also may differ among compatriots whose 'cultures' are a few hundred miles apart.[105]

Although existing studies have generally focused on gender views or attitudes that are work-related, there has so far not been a study on specific domestic roles. Supporting Hofstede's 1980 findings, that "high masculinity cultures are associated with low percentages of women holding professional and technical employment", test values for work-related egalitarianism were lower for Chinese than for Americans.[106] This is supported by the proportion of women that held professional jobs in China (far less than that of America), the data clearly indicating the limitations on opportunities open to women in contemporary Eastern society. In contrast, there was no difference between the viewpoint of Chinese and Americans regarding domestic gender roles.

A study by Richard Bagozzi, Nancy Wong and Youjae Yi, examines the interaction between culture and gender that produces distinct patterns of association between positive and negative emotions.[107] The United States was considered a more 'independence-based culture', while China was considered 'interdependence-based'. In the US people tend to experience emotions in terms of opposition whereas in China, they do so in dialectical terms (i.e., those of logical argumentation and contradictory forces). The study continued with sets of psychological tests among university students in Beijing and in Michigan. The fundamental goals of the research were to show that "gender differences in emotions are adaptive for the differing roles that males and females play in the culture". The evidence for differences in gender role was found during the socialization in work experiment, proving that "women are socialized to be more expressive of their feelings and to show this to a greater extent in facial expressions and gestures, as well as by verbal means".[107] The study extended to the biological characteristics of both gender groups — for a higher association between PA and NA hormones in memory for women, the cultural patterns became more evident for women than for men.

Communication

Gender communication is viewed as a form of intercultural communication; and gender is both an influence on and a product of communication.

Communication plays a large role in the process in which people become male or female because each gender is taught different linguistic practices. Gender is dictated by society through expectations of behavior and appearances, and then is shared from one person to another, by the process of communication.[108] Gender does not create communication, communication creates gender.[109]

For example, females are often more expressive and intuitive in their communication, but males tend to be instrumental and competitive. In addition, there are differences in accepted communication behaviors for males and females. To improve communication between genders, people who identify as either male or female must understand the differences between each gender.[110]

As found by Cara Tigue (McMaster University in Hamilton, Canada) the importance of powerful vocal delivery for women could not be underestimated, as famously described in accounts of Margaret Thatcher's years in power.)

Nonverbal communication

Hall published an observational study on nonverbal gender differences and discussed the cultural reasons for these differences.[111] In her study, she noted women smile and laugh more and have a better understanding of nonverbal cues. She believed women were encouraged to be more emotionally expressive in their language, causing them to be more developed in nonverbal communication.

Men, on the other hand, were taught to be less expressive, to suppress their emotions, and to be less nonverbally active in communication and more sporadic in their use of nonverbal cues. Most studies researching nonverbal communication described women as being more expressively and judgmentally accurate in nonverbal communication when it was linked to emotional expression; other nonverbal expressions were similar or the same for both genders.[112]

McQuiston and Morris also noted a major difference in men and women's nonverbal communication. They found that men tend to show body language linked to dominance, like eye contact and interpersonal distance, more than women.[113]

Communication and gender cultures

According to author Julia Wood, there are distinct communication 'cultures' for women and men in the US.[114] She believes that in addition to female and male communication cultures, there are also specific communication cultures for African Americans, older people, Native Americans, gay men, lesbians, and people with disabilities. According to Wood, it is generally thought that biological sex is behind the distinct ways of communicating, but in her opinion the root of these differences is gender.[115]

Maltz and Broker's research suggested that the games children play may contribute to socializing children into masculine and feminine gender roles:[116] for example, girls being encouraged to play "house" may promotes stereotypically feminine traits, and may promote interpersonal relationships as playing house does not necessarily have fixed rules or objectives; boys tended to play more competitive and adversarial team sports with structured, predetermined goals and a range of confined strategies.

Communication and sexual desire

Metts, et al.[117] explain that sexual desire is linked to emotions and communicative expression. Communication is central in expressing sexual desire and 'complicated emotional states', and is also the 'mechanism for negotiating the relationship implications of sexual activity and emotional meanings'.

Gender differences appear to exist in communicating sexual desire, for example, masculine people are generally perceived to be more interested in sex than feminine people, and research suggests that masculine people are more likely than feminine people to express sexual interest.[118]

This may be greatly affected by masculine people being less inhibited by social norms for expressing their desire, being more aware of their sexual desire or succumbing to the expectations of their cultures.[119] When feminine people employ tactics to show their sexual desire, they are typically more indirect in nature. On the other hand, it is known masculinity is associated with aggressive behavior in all mammals, and most likely explains at least part of the fact that masculine people are more likely to express their sexual interest. This is known as the Challenge hypothesis.

Various studies show different communication strategies with a feminine person refusing a masculine person's sexual interest. Some research, like that of Murnen,[120] show that when feminine people offer refusals, the refusals are verbal and typically direct. When masculine people do not comply with this refusal, feminine people offer stronger and more direct refusals. However, research from Perper and Weis[121] showed that rejection includes acts of avoidance, creating distractions, making excuses, departure, hinting, arguments to delay, etc. These differences in refusal communication techniques are just one example of the importance of communicative competence for both masculine and feminine gender cultures.

Gender stereotypes

General

A 1992 study tested gender stereotypes and labeling within young children in the United States.[122] Fagot et al. divided this into two different studies, the first investigated how children identified the differences between gender labels of boys and girls, the second study looked at both gender labeling and stereotyping in the relationship of mother and child.[122]

Within the first study, 23 children between the ages of 2 and 7 underwent a series of gender labeling and gender stereotyping tests consisting of showing the children either pictures of males and females or objects such as a hammer or a broom then identifying or labeling those to a certain gender. The results of these tests showed that children under 3 years could make gender-stereotypic associations.[122]

The second study looked at gender labeling and stereotyping in the relationship of mother and child using three separate methods. The first consisted of identifying gender labeling and stereotyping, essentially the same method as the first study. The second consisted of behavioral observations, which looked at ten-minute play sessions with mother and child using gender specific toys.

The third was a series of questionnaires such as an "Attitude Toward Women Scale", "Personal Attributes Questionnaire", and "Schaefer and Edgerton Scale" which looked at the family values of the mother.[122]

The results of these studies showed the same as the first study with regards to labeling and stereotyping.

They also identified in the second method that the mothers' positive reactions and responses to same-sex or opposite-sex toys played a role in how children identified them. Within the third method the results found that the mothers of the children who passed the "Gender Labeling Test", had more traditional family values. These two studies, conducted by Beverly I. Fagot, Mar D. Leinbach and Cherie O'Boyle, showed that gender stereotyping and labeling is acquired at a very young age, and that social interactions and associations play a large role in how genders are identified.[122]

Virginia Woolf, in the 1920s, made the point: 'It is obvious that the values of women differ very often from the values which have been made by the other sex. Yet it is the masculine values that prevail'[123] remade sixty years later by psychologist Carol Gilligan who used it to show that psychological tests of maturity have generally been based on masculine parameters, and so tended to show that women were less 'mature'. Gilligan countered this in her ground-breaking work, In a Different Voice, holding that maturity in women is shown in terms of different, but equally important, human values.[124]

Gender stereotypes are extremely common in society.[126][127] One of the reasons this may be is simply because it is easier on the brain to stereotype (see Heuristics).

The brain has limited perceptual and memory systems, so it categorizes information into fewer and simpler units which allows for more efficient information processing.[128] Gender stereotypes appear to have an effect at an early age. In one study, the effects of gender stereotypes on children's mathematical abilities were tested. In this study of American children between the ages of six and ten, it was found that the children, as early as the second grade, demonstrated the gender stereotype that mathematics is a 'boy's subject'. This may show that the mathematical self-belief is influenced before the age in which there are discernible differences in mathematical achievement.[129]

According to the 1972 study by Jean Lipman-Blumen, women who grew up following traditional gender roles from childhood were less likely to want to be highly educated while women brought up with the view that men and women are equal were more likely to want higher education. This result indicates that gender roles that have been passed down traditionally can influence stereotypes about gender.[130][131]

In a later study, Deaux and her colleagues (1984) found that most people think women are more nurturant, but less self-assertive than men. and that this belief is indicated universally, but that this awareness is related to women's role. To put it another way, women do not have an inherently nurturant personality, rather that a nurturing personality is acquired by whoever happens to be doing the housework.[132]

In a study of gender stereotypes by Jacobs (1991) it was found that parents' stereotypes interact with the sex of their child to directly influence the parents' beliefs about the child's abilities. In turn, parents' beliefs about their child directly influence their child's self-perceptions, and both the parents' stereotypes and the child's self-perceptions influence the child's performance.[133]

Stereotype threat is being at risk of confirming, as self-characteristic, a negative stereotype about one's group.[134] In the case of gender it is the implicit belief in gender stereotype that women perform worse than men in mathematics, which is proposed to lead to lower performance by women.[135]

A review article of stereotype threat research (2012) relating to the relationship between gender and mathematical abilities concluded "that although stereotype threat may affect some women, the existing state of knowledge does not support the current level of enthusiasm for this [as a] mechanism underlying the gender gap in mathematics".[136]

In 2018, Jolien A. van Breen and colleagues conducted research into subliminal gender stereotyping. Researchers took participants through a fictional Moral Choice Dilemma Task, which consisted of eight scenarios "in which sacrificing one person can save several others of unspecified gender. In four scenarios, participants are asked to sacrifice a man to save several others (of unspecified gender), and in four other scenarios they are asked to sacrifice a woman." The results showed that women who identified as feminists were more willing to 'sacrifice' men than women who did not identify as feminists.[137] "If a person wanted to counteract that and ‘level the playing field’, that can be done either by boosting women or by downgrading men”, said van Breen. “So I think that this effect on evaluations of men arises because our participants are trying to achieve an underlying aim: counteracting gender stereotypes."[138]

In the workplace

Gender stereotypes can disadvantage women during the hiring process.[139] It is one explanation for the lack of women in key organizational positions.[140] Management and similar leader positions are often perceived to be "masculine" in type, meaning they are assumed to require aggressiveness, competitiveness, strength and independence. These traits do not line up with the perceived traditional female gender role stereotype.[141] (This is often referred to as the "lack of fit" model which describes the dynamics of the gender bias.[142]) Therefore, the perception that women do not possess these "masculine" qualities, limits their ability to be hired or promoted into managerial positions.

One's performance at work is also evaluated based on one's gender. If a female and a male worker show the same performance, the implications of that performance vary depending on the person's gender and on who observes the performance; if a man performs exceedingly well he is perceived as driven or goal-oriented and generally seen in a positive light while a woman showing a similar performance is often described using adjectives with negative connotations.[143] Female performance is therefore not evaluated neutrally or unbiased and stereotyped in ways to deem their equivalent levels and quality of work as instead of lesser value.

Consequently, that gender stereotype filter leads to a lack of fair evaluation and, in turn, to fewer women occupying higher paying positions. Gender stereotypes contain women at certain, lower levels; getting trapped within the glass ceiling. While the number of women in the workforce occupying management positions is slowly increasing,[144] women currently fill only 2.5% of the higher managerial positions in the United States.[145] The fact that most women are being allocated to occupations that pay less, is often cited as a contributor to the existing gender pay gap.[146][147]

In relation to white women, women of color are disproportionally affected by the negative influence their gender has on their chances in the labor market.[148] In 2005, women held only 14.7% of Fortune 500 board seats with 79% of them being white and 21% being women of color.[145] This difference is understood through intersectionality, a term describing the multiple and intersecting oppressions and individual might experience. Activists during second-wave feminism have also used the term "horizontal oppressions" to describe this phenomenon.[149] It has also been suggested that women of color in addition to the glass ceiling, face a "concrete wall" or a "sticky floor" to better visualize the barriers.[145]

Liberal feminist theory states that due to these systemic factors of oppression and discrimination, women are often deprived of equal work experiences because they are not provided equal opportunities on the basis of legal rights. Liberal feminists further propose that an end needs to be put to discrimination based on gender through legal means, leading to equality and major economic redistributions.[150][151]

While activists have tried calling on Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to provide an equal hiring and promotional process, that practice has had limited success.[152] The pay gap between men and women is slowly closing. Women make approximately 21% less than her male counterpart according to the Department of Labor.[153] This number varies by age, race, and other perceived attributes of hiring agents. A proposed step towards solving the problem of the gender pay gap and the unequal work opportunities is the ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment which would constitutionally guarantee equal rights for women.[154][155][156][157] This is hoped to end gender-based discrimination and provide equal opportunities for women.

Economic and social consequences

If a woman does act according to female stereotypes, she is likely to receive backlash for not being competent enough; if she does not act according to the stereotypes connected to her gender and behaves more androgynous, or even masculine, it is likely to cause backlash through third-party punishment or further job discrimination.[158] Therefore, women are expected to behave in a way that aligns with female gender stereotypes while these stereotypes are simultaneously used to justify their lack of success in an economic context, putting women in the workforce in a precarious, "double bind" situation.[159] A proposed step to relieve women from this issue is the above-mentioned ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, as it would legally further gender equality and prohibit gender-based discrimination[160] regardless if a woman is acting according to female gender stereotypes or in defiance of them.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter identified four types of stereotypes given to professional women via the media. The four stereotypes are, iron maiden, pet, mother, and seductress/sex object.[161] Iron maiden refers to women who are deemed to display too many masculine traits and not enough feminine traits according to her audience. This leads audiences to question the trustworthiness of an iron maiden, because she is seen as strategically playing the field to appease voters. The pet stereotype is given to women who are identified as helpmates, cheerleaders, or mascots, which then leads the audience to see these women as naive or weak and unable to lead without a man's help. If a professional woman is seen as a mother, she is more likely to be seen as compassionate and caring, but also has the capacity to be shrew, punishing, and scolding. Additionally, it is possible for her leadership abilities to be called into question due to perceived conflicts with her maternal responsibilities. The fourth stereotype, seductress, is assigned to women who speak and act rather femininely, or have been victims of sexual harassment. The media tends to focus on the seductress woman's sex appeal and physical appearance in opposition to her policy stances and rhetoric.[162]

A proposed step to relieve women from that double bind is the above-mentioned ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment, as it would further legal gender equality and prohibit gender-based discrimination,[163] regardless if a woman is acting according to female gender stereotypes or in defiance of them.

Implicit gender stereotypes

Gender stereotypes and roles can also be supported implicitly. Implicit stereotypes are the unconscious influence of attitudes a person may or may not even be aware that he or she holds. Gender stereotypes can also be held in this manner.

These implicit stereotypes can often be demonstrated by the Implicit-association test (IAT).

One example of an implicit gender stereotype is that males are seen as better at mathematics than females. It has been found that men have stronger positive associations with mathematics than women, while women have stronger negative associations with mathematics and the more strongly a woman associates herself with the female gender identity, the more negative her association with mathematics.[164]

These associations have been disputed for their biological connection to gender and have been attributed to social forces that perpetuate stereotypes such as aforementioned stereotype that men are better at mathematics than women.[165]

This particular stereotype has been found in American children as early as second grade.[129]

The same test found that the strength of a Singaporean child's mathematics-gender stereotype and gender identity predicted the child's association between individuals and mathematical ability.[166]

It has been shown that this stereotype also reflects mathematical performance: a study was done on the worldwide scale and it was found that the strength of this mathematics-gender stereotype in varying countries correlates with 8th graders' scores on the TIMSS, a standardized math and science achievement test that is given worldwide. The results were controlled for general gender inequality and yet were still significant.[167]

Gender inequality online

An example of gender stereotypes assumes those of the male gender are more 'tech savvy' and happier working online, however, a study done by Hargittai & Shafer,[168] shows that many women also typically have lower self-perceived abilities when it comes to use of the World Wide Web and online navigation skills. Because this stereotype is so well known many women assume they lack such technical skills when in reality, the gap in technological skill level between men and women is significantly less than many women assume.

In the journal article written by Elizabeth Behm-Morawitz video games have been guilty of using sexualised female characters, who wear revealing clothing with an 'ideal' figure. It has been shown, female gamers can experience lower self-efficacy when playing a game with a sexualized female character. Women have been stereotyped in online games and have shown to be quite sexist in their appearances. It has been shown these kind of character appearances have influenced peoples' beliefs about gender capabilities by assigning certain qualities to the male and female characters in different games.[169]

The concept of gender inequality is often perceived as something that is non-existent within the online community, because of the anonymity possible online. Remote or home-working greatly reduces the volume of information one individual gives another compared to face-to-face encounters,[170] providing fewer opportunities for unequal treatment but it seems real-world notions of power and privilege are being duplicated: people who choose to take up different identities (avatars) in the online world are (still) routinely discriminated against, evident in online gaming where users are able to create their own characters. This freedom allows the user to create characters and identities with a different appearance than his or her own in reality, essentially allowing them to create a new identity, confirming that regardless of actual gender those who are perceived as female are treated differently.

In marked contrast to the traditional male-dominated stereotype a study shows that 52% of the gaming audience is made up of women and a minority of gaming characters are women. Only 12% of game designers in Britain and 3% of all programmers are women.[171]

Despite the growing number of women who partake in online communities, and the anonymous space provided by the Internet, issues such as gender inequality, the issue has simply been transplanted into the online world.

Politics and gender issues

In political office

Even though the number of women running for elected office has increased over the last decades, they still only make up 20% of U.S. senators, 19.4% of U.S. congressional representatives and 24% of statewide executives.[172] Additionally, many of these political campaigns appear to focus on the aggressiveness of the female candidate which is often still perceived as a masculine trait.[173] Therefore, female candidates are running based on gender-opposing stereotypes because that predicts higher likelihood of success than appearing to be a stereotypical woman.

Elections of increasing numbers of women into office serves as a basis for many scholars to claim that voters are not biased towards a candidate's gender. However, it has been shown that female politicians are perceived as only being superior when it comes to handling women's rights and poverty, whereas male politicians are perceived to be better at dealing with crime and foreign affairs.[174] That view lines up with the most common gender stereotypes.

It has also been predicted that gender does only highly matter for female candidates that have not been politically established. These predictions apply further to established candidates, stating that gender would not be a defining factor for their campaigns or the focal point of media coverage. This has been disproven by multiple scholars, often based on Hillary Clinton's multiple campaigns for the office of President of the United States.[175][176][177]

Additionally, when voters don't have a lot of information about a female candidate, they are likely to view her as being a stereotypical woman which they often take as a basis for not electing her because they consider typical male qualities as being crucial for someone holding a political office.[178]

Feminism and women's rights

Throughout the 20th century, women in the United States saw a dramatic shift in social and professional aspirations and norms. Following the Women's Suffrage Movement of the late-nineteenth century, which resulted in the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment allowing women to vote, and in combination with conflicts in Europe, WWI and WWII, women found themselves shifted into the industrial workforce. During this time, women were expected to take up industrial jobs and support the troops abroad through the means of domestic industry. Moving from "homemakers" and "caregivers", women were now factory workers and "breadwinners" for the family.

However, after the war, men returned home to the United States and women, again, saw a shift in social and professional dynamics. With the reuniting of the nuclear family, the ideals of American Suburbia boomed. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, middle-class families moved in droves from urban living into newly developed single-family homes on former farmland just outside major cities. Thus established what many modern critics describe as the "private sphere".[179] Though frequently sold and idealized as “perfect living”,[180] many women had difficulty adjusting to the new “private sphere.” Writer Betty Friedan described this discontent as “the feminine mystique.” The “mystique” was derived from women equipped with the knowledge, skills, and aspirations of the workforce, the “public sphere”, who felt compelled whether socially or morally to devote themselves to the home and family.[181]

One major concern of feminism, is that women occupy lower-ranking job positions than men, and do most of the housework.[182] A recent (October 2009) report from the Center for American Progress, "The Shriver Report: A Woman's Nation Changes Everything" tells us that women now make up 48% of the US workforce and "mothers are breadwinners or co-breadwinners in a majority of families" (63.3%, see figure 2, page 19 of the Executive Summary of The Shriver Report).[183]

Another recent article in The New York Times indicates that young women today are closing the pay gap. Luisita Lopez Torregrosa has noted, "Women are ahead of men in education (last year, 55 percent of U.S. college graduates were female). And a study shows that in most U.S. cities, single, childless women under 30 are making an average of 8 percent more money than their male counterparts, with Atlanta and Miami in the lead at 20 percent.".[184] While this study concerned American cities, a global trend is developing, and has now been termed "the reverse gender gap."

Feminist theory generally defines gender as a social construct that includes ideologies governing feminine/masculine (female/male) appearances, actions, and behaviors. An example of these gender roles would be that males were supposed to be the educated breadwinners of the family, and occupiers of the public sphere whereas, the female's duty was to be a homemaker, take care of her husband and children, and occupy the private sphere. According to contemporary gender role ideology, gender roles are continuously changing. This can be seen in Londa Schiebinger's Has Feminism Changed Science, in which she states, "Gendered characteristics - typically masculine or feminine behaviors, interests, or values-are not innate, nor are they arbitrary. They are formed by historical circumstances. They can also change with historical circumstances."[185]

One example of the contemporary definition of gender was depicted in Sally Shuttleworth’s Female Circulation in which the, “abasement of the woman, reducing her from an active participant in the labor market to the passive bodily existence to be controlled by male expertise is indicative of the ways in which the ideological deployment of gender roles operated to facilitate and sustain the changing structure of familial and market relations in Victorian England.”[186] In other words, this shows what it meant to grow up into the roles (gender roles) of a female in Victorian England, which transitioned from being a homemaker to being a working woman and then back to being passive and inferior to males. In conclusion, gender roles in the contemporary sex gender model are socially constructed, always changing, and do not really exist since they are ideologies that society constructs in order for various benefits at various times in history.

Men's rights

.jpg)

The men's rights movement (MRM) is a part of the larger men's movement. It branched off from the men's liberation movement in the early-1970s. The men's rights movement is made up of a variety of groups and individuals who are concerned about what they consider to be issues of male disadvantage, discrimination and oppression.[187][188] The movement focuses on issues in numerous areas of society (including family law, parenting, reproduction, domestic violence) and government services (including education, compulsory military service, social safety nets, and health policies) that they believe discriminate against men.

Scholars consider the men's rights movement or parts of the movement to be a backlash to feminism.[189] The men's rights movement denies that men are privileged relative to women.[190] The movement is divided into two camps: those who consider men and women to be harmed equally by sexism, and those who view society as endorsing the degradation of men and upholding female privilege.[190]

Men's rights groups have called for male-focused governmental structures to address issues specific to men and boys including education, health, work and marriage.[191][192][193] Men's rights groups in India have called for the creation of a Men's Welfare Ministry and a National Commission for Men, as well as the abolition of the National Commission for Women.[191][194][195] In the United Kingdom, the creation of a Minister for Men analogous to the existing Minister for Women, have been proposed by David Amess, MP and Lord Northbourne, but were rejected by the government of Tony Blair.[192][196][197] In the United States, Warren Farrell heads a commission focused on the creation of a "White House Council on Boys and Men" as a counterpart to the "White House Council on Women and Girls" which was formed in March 2009.[193][198]

Related to this is the Father's Rights Movement, whose members seek social and political reforms that affect fathers and their children.[199] These individuals contest that societal institutions such as family courts, and laws relating to child custody and child support payments, are gender biased in favor of mothers as the default caregiver. They therefore are systemically discriminatory against males regardless of their actual caregiving ability, because males are typically seen as the bread-winner, and females as the care-giver.[200]

Gender neutrality

Gender neutrality is the movement to end discrimination of gender altogether in society through means of gender neutral language, the end of sex segregation and other means.

Transgender and cross-dressing

Transgender is the state of one's gender identity or gender expression not matching one's assigned sex.[201] Transgender is independent of sexual orientation; transgender people may identify as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, etc.; some may consider conventional sexual orientation labels inadequate or inapplicable to them. The definition of transgender includes:

- "Denoting or relating to a person whose sense of personal identity and gender does not correspond with their birth sex."[202]

- "People who were assigned a sex, usually at birth and based on their genitals, but who feel that this is a false or incomplete description of themselves."[203]

- "Non-identification with, or non-presentation as, the sex (and assumed gender) one was assigned at birth."[204]

While people self-identify as transgender, the transgender identity umbrella includes sometimes-overlapping categories. These include transsexual; transvestite or cross-dresser; genderqueer; androgyne; and bigender.[205] Usually not included are transvestic fetishists (because it is considered to be a paraphilia rather than gender identification), and drag kings and drag queens, who are performers who cross-dress for the purpose of entertaining. In an interview, celebrity drag queen RuPaul talked about society's ambivalence to the differences in the people who embody these terms. "A friend of mine recently did the Oprah show about transgender youth", said RuPaul. "It was obvious that we, as a culture, have a hard time trying to understand the difference between a drag queen, transsexual, and a transgender, yet we find it very easy to know the difference between the American baseball league and the National baseball league, when they are both so similar."[206]

Sexual orientation

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

Issues

|

|

Academic fields and discourse |

|

|

Sexual orientation is defined by the interplay between a person's emotional and physical attraction toward others.[207] Generally, sexual orientation is broken into the three categories: heterosexual, homosexual and bisexual. By basic definition, the term heterosexual is typically used in reference to someone who is attracted to people of the opposite sex, the term homosexual is used to classify people who are attracted to those of the same sex, and the term bisexual is used to identify those who are attracted to both the same and opposite sexes.[208] Sexual orientation can be variously defined based on sexual identity, sexual behavior and sexual attraction. People can fall anywhere on a spectrum from strictly heterosexual to strictly homosexual.[209]

Scientists do not know the exact cause of sexual orientation, but they theorize that it is caused by a complex interplay of genetic, hormonal, and environmental influences,[210][211][212] and do not view it as a choice.[210][211][213] Although no single theory on the cause of sexual orientation has yet gained widespread support, scientists favor biologically-based theories.[210] There is considerably more evidence supporting nonsocial, biological causes of sexual orientation than social ones, especially for males.[214][215][216] There is no substantive evidence which suggests parenting or early childhood experiences play a role with regard to sexual orientation.[217]

An active conflict over the cultural acceptability of non-heterosexuality rages worldwide.[218][219][220][221][222] The belief or assumption that heterosexual relationships and acts are "normal" is described as heterosexism or in queer theory, heteronormativity. Gender identity and sexual orientation are two separate aspects of individual identity, although they are often mistaken in the media.[223]

Perhaps it is an attempt to reconcile this conflict that leads to a common assumption that one same-sex partner assumes a pseudo-male gender role and the other assumes a pseudo-female role. For a gay male relationship, this might lead to the assumption that the "wife" handled domestic chores, was the receptive sexual partner, adopted effeminate mannerisms, and perhaps even dressed in women's clothing.[224] This assumption is flawed because homosexual couples tend to have more equal roles, and the effeminate behavior of some gay men is usually not adopted consciously, and is often more subtle.[225]

Cohabitating same-sex partners are typically egalitarian when they assign domestic chores.[226] Sometimes these couples assign traditional female responsibilities to one partner and traditional male responsibilities to the other. Same-sex domestic partners challenge traditional gender roles in their division of household responsibilities, and gender roles within homosexual relationships are flexible.[227] For instance, cleaning and cooking, traditionally regarded by many as both female responsibilities, might be assigned to different people. Carrington observed the daily home lives of 52 gay and lesbian couples and found that the length of the work week and level of earning power substantially affected the assignment of housework, regardless of gender or sexuality.[228][229]

In many cultures, gender roles, especially for men, simultaneously act as an indicator for heterosexuality, and as a boundary of acceptable behavior for straight people. Therefore, lesbians, gay men and bisexual people may be viewed as exempt from some or all components of gender roles or as having different "rules" they are expected to follow by society.

These modified "rules" for lesbian, gay and bisexual people may also be oppressive. Morgan examines the plight of homosexuals seeking asylum from homophobic persecution who have been turned away by US customs for "not being gay enough"; not conforming sufficiently to standard (Western) conceptions of the gender roles occupied by gays and lesbians.[230]

Conversely, heterosexual men and women who are not perceived as being sufficiently masculine or feminine, respectively, may be assumed to be, or suspected to be, homosexual, and persecuted for their perceived homosexuality.

Criminal justice

A number of studies conducted since the mid-90s have found direct correlation between a female criminal's ability to conform to gender role stereotypes and the severity of her sentencing, particularly among female murderers.[231][232][233][234] "In terms of the social realities of justice in America, the experiences of diverse groups of people in society have contributed to the shaping of the types of criminals and victims that we have had. Like Andersen and Hill Collins (1998: 4) in their discussion of what they refer to as a 'matrix of domination,' we too conceive that class, race, and gender represent "multiple, interlocking levels of domination that stem from the societal configurations of these structural relationships. These patterned actions, in turn, affecting individual consciousness, group interaction, and individual and group access to institutional power and privileges.'"[235] "Patterns of offending by men and by women are notable both for their similarities and for their differences. Both men and women are more heavily involved in minor property and substance abuse offenses than in serious crimes like robbery or murder. However, men offend at much higher rates than women for all crime categories except prostitution. This gender gap in crime is greatest for serious crime and least for mild forms of lawbreaking such as minor property crimes." [236]

Gender roles in family violence

The ‘Family Violence Framework’ applies gender dynamics to family violence.[237][238] “Families are constructed around relationships that involve obligations and responsibilities, but also status and power”.[237] According to Hattery and Smith, when “masculinity and femininity are constructed…to generate these rigid and narrow gender roles, it contributes to a culture of violence against women”[239] “People with more resources are more likely to be abusive towards those without resources”, meaning that the stronger member of the relationship abuses the weaker partner or family member.[237] However, the fight for power and equality remains – “Intimate partner violence in same-sex couples reveals that the rates are similar to those in the heterosexual community”.[240]

See also

- Anti-gender movement

- Childhood gender nonconformity

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women

- Dominatrix

- Gender advertisement

- Gender and emotional expression

- Gender mainstreaming

- Gender polarization

- Gender policing

- Gender roles in childhood

- Gender roles in non-heterosexual communities

- Gender studies

- Grammatical gender

- Heteropatriarchy

- List of transgender-related topics

- Marriage gap

- Masculism

- Matriarchy

- Media and gender

- Men's movement

- Misandry

- Patriarchy

- Role theory

- Sex and gender distinction

- Sexual inversion (sexology)

- Sexual orientation hypothesis

- Social construction of gender

- Sociology of gender

- Women in Christianity

- Women in Islam

- Yogyakarta Principles

References

- Levesque R.J.R. (2011) Sex Roles and Gender Roles. In: Levesque R.J.R. (eds) Encyclopedia of Adolescence. Springer, New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-4419-1695-2. Retrieved January 22, 2018.

- Alters, Sandra; Schiff, Wendy (2009). Essential Concepts for Healthy Living. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 978-0763756413. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- David S. Gochman (2013). Handbook of Health Behavior Research II: Provider Determinants. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 424. ISBN 978-1489917607. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- Janssen, D.F. (2018). "Know Thy Gender: Etymological Primer". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 47 (8): 2149–2154. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1300-x. ISSN 0004-0002. PMID 30182204.

- "What do we mean by "sex" and "gender"?". WHO.int. World Health Organization. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015. Retrieved 18 August 2015.

- The social construction of race. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/05/the-social-construction-of-race/275974/

- Henry, S. (2009) Social construction of crime. In J. Miller (Ed.), 21st Century criminology: A reference handbook. (pp. 296-306). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:10.4135/9781412971997.n34

- Hacking, I (1999) The social construction of what?. Harvard University Press.

- http://www.aifs.gov.au/conferences/aifs7/francis.html