East Timor

East Timor (/-ˈtiːmɔːr/ (![]()

Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste

| |

|---|---|

Motto: Unidade, Acção, Progresso (Portuguese) Unidade, Asaun, Progresu (Tetum) (English: "Unity, Action, Progress") | |

.svg.png) | |

| Capital and largest city | Dili 8.55°S 125.56°E |

| Official languages | |

| National languages | |

| Religion (2015 census)[1] |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic[4][5][6] |

| Francisco Guterres | |

| José Maria Vasconcelos | |

| Legislature | National Parliament |

| Independence | |

| 16th century | |

• Independence declared | 28 November 1975 |

| 17 July 1976 | |

• Administered by UNTAET | 25 October 1999 |

• Independence restored | 20 May 2002 |

| Area | |

• Total | 15,007[7] km2 (5,794 sq mi) (154th) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

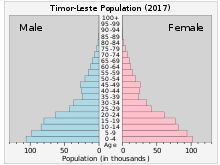

| Population | |

• 2015 census | 1,183,643[8] |

• Density | 78/km2 (202.0/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $7.221 billion |

• Per capita | $5,561[9] |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $3.145 billion |

• Per capita | $2,422[9] |

| HDI (2018) | medium · 131st |

| Currency | United States dollarb Indonesian Rupiah (minor) |

| Time zone | UTC+9 |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +670 |

| ISO 3166 code | TL |

| Internet TLD | .tlc |

Website timor-leste.gov.tl | |

| |

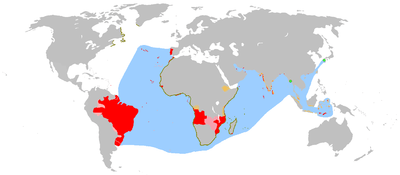

East Timor was colonised by Portugal in the 16th century, and was known as Portuguese Timor until 28 November 1975, when the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin) declared the territory's independence. Nine days later, it was invaded and occupied by the Indonesian military; it was declared Indonesia's 27th province the following year. The Indonesian occupation of East Timor was characterised by a highly violent, decades-long conflict between separatist groups (especially Fretilin) and the Indonesian military.

In 1999, following the United Nations-sponsored act of self-determination, Indonesia relinquished control of the territory. As "Timor-Leste", it became the first new sovereign state of the 21st century on 20 May 2002 and joined the United Nations[15] and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries.[16] In 2011, East Timor announced its intention to become the eleventh member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).[17] It is one of only two predominantly Christian nations in Southeast Asia, the other being the Philippines,[18] as well as the only country of Asia to be located completely in the Southern Hemisphere.[19]

Etymology

"Timor" is derived from timur, the word for "east" in Malay, which became recorded as Timor in Portuguese, thus resulting in the tautological toponym meaning "East East": In Portuguese Timor-Leste (Leste being the word for "east"); in Tetum Timór Lorosa'e (Lorosa'e being the word for "east" (literally "rising sun")). In Indonesian, the country is called Timor Timur, thereby using the Portuguese name for the island followed by the word for "east", as adjectives in Indonesian are put after the noun.

The official names under the Constitution are Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste in English,[20] República Democrática de Timor-Leste in Portuguese,[12] and Repúblika Demokrátika Timór-Leste in Tetum.[13]

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) official short form in English and all other languages is Timor-Leste (codes: TLS & TL), which has been adopted by the United Nations,[21] the European Union,[22] and the national standards organisations of France (AFNOR), the United States (ANSI),[23] United Kingdom (BSI), Germany (DIN), and Sweden (SIS), all diplomatic missions to the country by protocol and the CIA World Factbook.[24]

History

Prehistory

Cultural remains at Jerimalai on the eastern tip of East Timor have been dated to 42,000 years ago, making that location one of the oldest known sites of modern human activity in Maritime Southeast Asia.[25] Descendants of at least three waves of migration are believed still to live in East Timor. The first is described by anthropologists as people of the Veddo-Australoid type. Around 3000 BC, a second migration brought Melanesians. The earlier Veddo-Australoid peoples withdrew at this time to the mountainous interior. Finally, proto-Malays arrived from south China and north Indochina.[26] Hakka traders are among those descended from this final group.[27]

Timorese origin myths tell of ancestors who sailed around the eastern end of Timor arriving on land in the south. Some stories recount Timorese ancestors journeying from the Malay Peninsula or the Minangkabau highlands of Sumatra.[28] Austronesians migrated to Timor, and are thought to be associated with the development of agriculture on the island.

Classical era

Before European colonialism, Timor was included in Indonesian/Malaysian, Chinese and Indian trading networks, and in the 14th century was an exporter of aromatic sandalwood, slaves, honey, and wax. From the 1500s, the Timorese people had military ties with the Luções of present-day northern Philippines.[29][30] It was the relative abundance of sandalwood in Timor that attracted European explorers to the island in the early 16th century.[31] At around that time, European explorers reported that the island had a number of small chiefdoms or princedoms.

Colonial era

Portuguese period (1769–1975)

The Portuguese established outposts in Timor and Maluku. Effective European occupation of a small part of present day East Timor began in 1769, when the city of Dili was founded and the colony of Portuguese Timor declared.[33] A definitive border between the Dutch-colonised western half of the island and the Portuguese-colonised eastern half was established by the Permanent Court of Arbitration of 1914,[34] and it remains the international boundary between the successor states Indonesia and East Timor, respectively. For the Portuguese, East Timor remained little more than a neglected trading post until the late nineteenth century, with minimal investment in infrastructure, health, and education. Sandalwood continued to be the main export crop with coffee exports becoming significant in the mid-nineteenth century.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, a faltering home economy prompted the Portuguese to extract greater wealth from its colonies, which was met with East Timorese resistance.[35]

During World War II, first the Allies and later the Japanese occupied Dili, and the mountainous interior of the colony became the scene of a guerrilla campaign, known as the Battle of Timor. Waged by East Timorese volunteers and Allied forces against the Japanese, the struggle resulted in the deaths of between 40,000 and 70,000 East Timorese.[36] The Japanese eventually drove the last of the Australian and Allied forces out. However, Portuguese control was reinstated after the Japanese surrender at the end of World War II.

Following the 1974 Portuguese revolution, Portugal effectively abandoned its colony in Timor and civil war between East Timorese political parties broke out in 1975.

The Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (Fretilin) resisted a Timorese Democratic Union (UDT) coup attempt in August 1975,[37] and unilaterally declared independence on 28 November 1975. Fearing a communist state within the Indonesian archipelago, the Indonesian military launched an invasion of East Timor in December 1975.[38] Indonesia declared East Timor its 27th province on 17 July 1976.[39] The UN Security Council opposed the invasion and the territory's nominal status in the UN remained as "non-self-governing territory under Portuguese administration".[40]

Indonesian occupation (1975–1999)

Indonesia's occupation of East Timor was marked by violence and brutality. A detailed statistical report prepared for the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor cited a minimum of 102,800 conflict-related deaths in the period 1974–1999, namely, approximately 18,600 killings and 84,200 "excess" deaths from hunger and illness, with an estimated figure based on Portuguese, Indonesian and Catholic Church data of approximately 200,000 deaths.[41] The East Timorese guerrilla force (Forças Armadas da Libertação Nacional de Timor-Leste, Falintil) fought a campaign against the Indonesian forces from 1975 to 1998.

The 1991 Dili Massacre was a turning point for the independence cause and an East Timor solidarity movement grew in Portugal, the Philippines, Australia, and other Western countries.

Following the resignation of Indonesian President Suharto, a UN-sponsored agreement between Indonesia and Portugal allowed for a UN-supervised popular referendum in August 1999. A clear vote for independence was met with a punitive campaign of violence by East Timorese pro-integration militia supported by elements of the Indonesian military. With Indonesian permission, an Australian-led multi-national peacekeeping force (INTERFET) was deployed until order was restored. On 25 October 1999, the administration of East Timor was taken over by the UN through the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET), headed by Sergio Vieira de Mello.[42][43] The INTERFET deployment ended in February 2000 with the transfer of military command to the UN.[44]

Contemporary era

On 30 August 2001, the East Timorese voted in their first election organised by the UN to elect members of the Constituent Assembly.[20][45] On 22 March 2002, the Constituent Assembly approved the Constitution.[20] By May 2002, over 205,000 refugees had returned.[46] On 20 May 2002, the Constitution of the Democratic Republic of East Timor came into force and East Timor was recognised as independent by the UN.[45][47] The Constituent Assembly was renamed the National Parliament and Xanana Gusmão was sworn in as the country's first President after Indonesian occupation. On 27 September 2002, East Timor was renamed Timor-Leste, using the Portuguese language, and was admitted as a member state by the UN.[48]

In 2006, the United Nations sent in security forces to restore order when unrest and factional fighting forced 15 percent of the population (155,000 people) to flee their homes.[49] The following year, Gusmão declined another presidential term, and in the build-up to the mid-year presidential elections there were renewed outbreaks of violence. In those elections, José Ramos-Horta was elected President.[50] In June 2007, Gusmão ran in the parliamentary elections and became Prime Minister. In February 2008, Ramos-Horta was critically injured in an attempted assassination. Prime Minister Gusmão also faced gunfire separately but escaped unharmed. Australian reinforcements were immediately sent to help keep order.[51] In March 2011, the UN handed over operational control of the police force to the East Timor authorities. The United Nations ended its peacekeeping mission on 31 December 2012.[49]

East Timor became a state party to the UNESCO World Heritage Convention on 31 January 2017.[52]

Politics and government

The head of state of East Timor is the President of the Republic, who is elected by popular vote for a five-year term. Although the President's executive powers are somewhat limited, he or she does have the power to appoint the Prime Minister and veto government legislation. Following elections, the President usually appoints the leader of the majority party or coalition as Prime Minister of East Timor and the cabinet on the proposal of the latter. As head of government, the Prime Minister presides over the cabinet.[4][5]

The unicameral East Timorese parliament is the National Parliament or Parlamento Nacional, the members of which are elected by popular vote to a five-year term. The number of seats can vary from a minimum of fifty-two to a maximum of sixty-five. The East Timorese constitution was modelled on that of Portugal. The country is still in the process of building its administration and governmental institutions. Government departments include the Polícia Nacional de Timor-Leste (police), East Timor Ministry for State and Internal Administration, Civil Aviation Division of Timor-Leste, and Immigration Department of Timor-Leste.

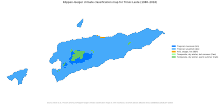

Administrative divisions

East Timor is divided into thirteen municipalities, which in turn are subdivided into 65 administrative posts, 442 sucos (villages), and 2,225 aldeias (hamlets).[53][54]

- Oecusse

- Liquiçá

- Dili

- Manatuto

- Baucau

- Lautém

- Bobonaro

- Ermera

- Aileu

- Viqueque

- Cova Lima

- Ainaro

- Manufahi

Articles 5 and 71 of the 2002 constitution provide that Oecusse be governed by a special administrative policy and economic regime. Law 3/2014 of 18 June 2014 created the Special Administrative Region of Oe-Cusse Ambeno (Região Administrativa Especial de Oecusse, RAEOA).[55]

Foreign relations and military

East Timor is a full member state of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth, an international organisation and political association of Lusophone nations across four continents. In each of those nations, Portuguese is an official language. East Timor sought membership in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2007, and a formal application was submitted in March 2011.[56]

The East Timor Defence Force (Forças de Defesa de Timor-Leste, F-FDTL) is the military body responsible for the defence of East Timor. The F-FDTL was established in February 2001 and comprised two small infantry battalions, a small naval component, and several supporting units.

The F-FDTL's primary role is to protect East Timor from external threats. It also has an internal security role, which overlaps with that of the National Police of East Timor (Polícia Nacional de Timor-Leste, PNTL). This overlap has led to tensions between the services, which have been exacerbated by poor morale and lack of discipline within the F-FDTL.

The F-FDTL's problems came to a head in 2006 when almost half the force was dismissed following protests over discrimination and poor conditions. The dismissal contributed to a general collapse of both the F-FDTL and PNTL in May and forced the government to request foreign peacekeepers to restore security. The F-FDTL is being rebuilt with foreign assistance and has drawn up a long-term force development plan.

Since the discovery of petroleum in the Timor Sea in the 1970s, there have been disputes surrounding the rights to ownership and exploitation of the resources situated in a part of the Timor Sea known as the Timor Gap, which is the area of the Timor Sea which lies outside the territorial boundaries of the nations to the north and south of the Timor Sea.[57] These disagreements initially involved Australia and Indonesia, although a resolution was eventually reached in the form of the Timor Gap Treaty. After declaration of East Timor's nationhood in 1999, the terms of the Timor Gap Treaty were abandoned and negotiations commenced between Australia and East Timor, culminating in the Timor Sea Treaty.

Australia's territorial claim extended to the bathymetric axis (the line of greatest sea-bed depth) at the Timor Trough. It overlapped East Timor's own territorial claim, which followed the former colonial power Portugal and the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea in claiming that the dividing line should be midway between the two countries.

It was revealed in 2013 that the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) planted listening devices to listen to the East Timorese government during negotiations over the Greater Sunrise oil and gasfields. This is known as the Australia–East Timor spying scandal.[58]

Geography

Located in Southeast Asia,[59] the island of Timor is part of Maritime Southeast Asia, and is the largest and easternmost of the Lesser Sunda Islands. To the north of the island are the Ombai Strait, Wetar Strait, and the greater Banda Sea. The Timor Sea separates the island from Australia to the south, and the Indonesian province of East Nusa Tenggara lies to East Timor's west. The total land size is 14,919 km2 (5,760 sq mi). East Timor has an exclusive economic zone of 70,326 km2 (27,153 sq mi).[60]

Much of the country is mountainous, and its highest point is Tatamailau (also known as Mount Ramelau) at 2,963 metres (9,721 ft).[61] The climate is tropical and generally hot and humid. It is characterised by distinct rainy and dry seasons. The capital, largest city, and main port is Dili, and the second-largest city is the eastern town of Baucau. East Timor lies between latitudes 8° and 10°S, and longitudes 124° and 128°E.

The easternmost area of East Timor consists of the Paitchau Range and the Lake Ira Lalaro area, which contains the country's first conservation area, the Nino Konis Santana National Park.[62] It contains the last remaining tropical dry forested area within the country. It hosts a number of unique plant and animal species and is sparsely populated.[63] The northern coast is characterised by a number of coral reef systems that have been determined to be at risk.[64]

Economy

(previous_and_data).png)

.jpg)

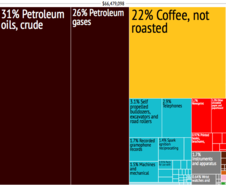

The economy of East Timor is a market economy, which used to depend upon exports of a few commodities such as coffee, marble, petroleum, and sandalwood.[65] It grew by about 10% in 2011 and at a similar rate in 2012.[66]

East Timor now has revenue from offshore oil and gas reserves, but little of it has been spent on the development of villages, which still rely on subsistence farming.[67] As of 2012, nearly half the East Timorese population was living in extreme poverty.[67]

The Timor-Leste Petroleum Fund was established in 2005, and by 2011 it had reached a worth of US$8.7 billion.[68] East Timor is labelled by the International Monetary Fund as the "most oil-dependent economy in the world".[69] The Petroleum Fund pays for nearly all of the government's annual budget, which increased from $70 million in 2004 to $1.3 billion in 2011, with a $1.8 billion proposal for 2012.[68] East-Timor's income from oil and gas stands to increase significantly after its cancellation of a controversial agreement with Australia, which gave Australia half of the income from oil and gas from 2006.[70]

The country's economy is dependent on government spending and, to a lesser extent, assistance from foreign donors.[71] Private sector development has lagged due to human capital shortages, infrastructure weakness, an incomplete legal system, and an inefficient regulatory environment.[71] After petroleum, the second largest export is coffee, which generates about $10 million a year.[71] Starbucks is a major purchaser of East Timorese coffee.[72]

9,000 tonnes of coffee, 108 tonnes of cinnamon and 161 tonnes of cocoa were harvested in 2012 making the country the 40th ranked producer of coffee, the 6th ranked producer of cinnamon and the 50th ranked producer of cocoa worldwide.[73]

According to data gathered in the 2010 census, 87.7% of urban (321,043 people) and 18.9% of rural (821,459 people) households have electricity, for an overall average of 38.2%.[74]

The agriculture sector employs 80% of East Timor's active population.[75] In 2009, about 67,000 households grew coffee in East Timor, with a large proportion of those households being poor.[75] Currently, the gross margins are about $120 per hectare, with returns per labour-day of about $3.70.[75] There were 11,000 households growing mungbeans as of 2009, most of them by subsistence farming.[75]

In the Doing Business 2013 report by the World Bank, East Timor was ranked 169th overall and last in the East Asia and Pacific region. The country fared particularly poorly in the "registering property", "enforcing contracts" and "resolving insolvency" categories, ranking last worldwide in all three.[76]

As regards telecommunications infrastructure, East Timor is the second to last ranked Asian country in the World Economic Forum's Network Readiness Index (NRI), with only Myanmar falling behind it in southeast Asia. NRI is an indicator for determining the development level of a country's information and communication technologies. In the 2014 NRI ranking, East Timor ranked number 141 overall, down from 134 in 2013.[77]

The Portuguese colonial administration granted concessions to the Australia-bound Oceanic Exploration Corporation to develop petroleum and natural gas deposits in the waters southeast of Timor. However, this was curtailed by the Indonesian invasion in 1976. The resources were divided between Indonesia and Australia with the Timor Gap Treaty in 1989.[78] East Timor inherited no permanent maritime boundaries when it attained independence. A provisional agreement (the Timor Sea Treaty, signed when East Timor became independent on 20 May 2002) defined a Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA) and awarded 90% of revenues from existing projects in that area to East Timor and 10% to Australia.[79] An agreement in 2005 between the governments of East Timor and Australia mandated that both countries put aside their dispute over maritime boundaries and that East Timor would receive 50% of the revenues from the resource exploitation in the area (estimated at A$26 billion, or about US$20 billion over the lifetime of the project)[80] from the Greater Sunrise development.[81] In 2013, East Timor launched a case at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague to pull out of a gas treaty that it had signed with Australia, accusing the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) of bugging the East Timorese cabinet room in Dili in 2004.[82] East Timor is part of the Timor Leste–Indonesia–Australia Growth Triangle (TIA-GT).[83]

There are no patent laws in East Timor.[84]

A railway system has been proposed but the current government has yet to approve the proposal due to lack of funds and expertise.

Tourism

Tourism is still of minor importance in East Timor. In 2017, the country was visited by 75,000 tourists.[85] In the last five years tourism has been increasing and the number of hotels and resorts has increased. The government decided to invest in the expansion of the international airport in Dili.

The risk for tourists in East Timor is medium / low, with positive factors being low crime, the occurrence of zero terrorist attacks in the last decades and road safety. Negative factors for tourists include roads in poor condition, mainly in the interior of the country.[86][87]

Demographics

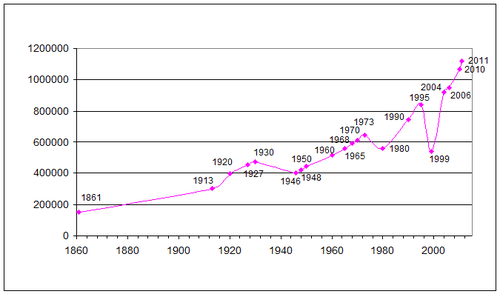

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 555,350 | — |

| 1990 | 747,557 | +3.02% |

| 2001 | 787,340 | +0.47% |

| 2004 | 923,198 | +5.45% |

| 2010 | 1,066,582 | +2.44% |

| 2015 | 1,183,643 | +2.10% |

| Source: 2015 census[88] | ||

East Timor recorded a population of 1,183,643 in its 2015 census.[8]

The CIA's World Factbook lists the English-language demonym for East Timor as Timorese,[89] as does the Government of Timor-Leste's website.[90] Other reference sources list it as East Timorese.[91][92]

The word Maubere,[93] formerly used by the Portuguese to refer to native East Timorese and often employed as synonymous with the illiterate and uneducated, was adopted by Fretilin as a term of pride.[94] Native East Timorese consist of a number of distinct ethnic groups, most of whom are of mixed Austronesian and Melanesian/Papuan descent. The largest Malayo-Polynesian ethnic groups are the Tetum[95] (100,000), primarily in the north coast and around Dili; the Mambai (80,000), in the central mountains; the Tukudede (63,170), in the area around Maubara and Liquiçá; the Galoli (50,000), between the tribes of Mambae and Makasae; the Kemak (50,000) in north-central Timor island; and the Baikeno (20,000), in the area around Pante Macassar.

The main tribes of predominantly Papuan origin include the Bunak (84,000), in the central interior of Timor island; the Fataluku (40,000), at the eastern tip of the island near Lospalos; and the Makasae (70,000), toward the eastern end of the island. As a result of interracial marriage which was common during the Portuguese era, there is a population of people of mixed East Timorese and Portuguese origin, known in Portuguese as mestiços. There is a small Chinese minority, most of whom are Hakka.[96] Many Chinese left in the mid-1970s.[97]

Languages

East Timor's two official languages are Portuguese and Tetum. English and Indonesian are sometimes used.[98] Tetum belongs to the Austronesian family of languages spoken throughout Southeast Asia and the Pacific.[99]

The 2015 census found that the most commonly spoken mother tongues were Tetum Prasa (mother tongue for 30.6% of the population), Mambai (16.6%), Makasai (10.5%), Tetum Terik (6.05%), Baikenu (5.87%), Kemak (5.85%), Bunak (5.48%), Tokodede (3.97%), and Fataluku (3.52%). Other indigenous languages accounted for 10.47%, while 1.09% of the population spoke foreign languages natively.[100]

Under Indonesian rule, the use of Portuguese was banned and only Indonesian was allowed to be used in government offices, schools and public business.[101] During the Indonesian occupation, Tetum and Portuguese were important unifying elements for the East Timorese people in opposing Javanese culture.[102] Portuguese was adopted as one of the two official languages upon independence in 2002 for this reason and as a link to Lusophone nations in other parts of the world. It is now being taught and promoted with the help of Brazil, Portugal, and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries.[103]

According to the observatory of the Portuguese language, the East Timorese literacy rate was 77.8% in Tetum, 55.6% in Indonesian, and 39.3% in Portuguese, and that the primary literacy rate increased from 73% in 2009 to 83% in 2012.[104] Indonesian and English are defined as working languages under the Constitution in the Final and Transitional Provisions, without setting a final date. In 2012, 35% could speak, read, and write Portuguese, which is up significantly from less than 5% in the 2006 UN Development Report. Portuguese is recovering as it is now been made the main official language of Timor, and is being taught in most schools.[98][105] It is estimated that English is understood by 31.4% of the population. East Timor is a member of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth) and of the Latin Union.[106]

Aside from Tetum, Ethnologue lists the following indigenous languages: Adabe, Baikeno, Bunak, Fataluku, Galoli, Habun, Idaté, Kairui-Midiki, Kemak, Lakalei, Makasae, Makuv'a, Mambae, Nauete, Tukudede, and Waima'a.[107] According to the Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger, there are six endangered languages in East Timor: Adabe, Habu, Kairui-Midiki, Maku'a, Naueti, and Waima'a.[108]

Education

East Timor's adult literacy rate in 2010 was 58.3%, up from 37.6% in 2001.[109] At the end of Portuguese rule, illiteracy was at 95%.[110]

The country's main university is the National University of East Timor. There are also four colleges.[111]

Since independence, both Indonesian and Tetum have lost ground as media of instruction, while Portuguese has increased: in 2001 only 8.4% of primary school and 6.8% of secondary school students attended a Portuguese-medium school; by 2005 this had increased to 81.6% for primary and 46.3% for secondary schools.[112] Indonesian formerly played a considerable role in education, being used by 73.7% of all secondary school students as a medium of instruction, but by 2005 Portuguese was used by most schools in Baucau, Manatuto, as well as the capital district.[112]

The Philippines has sent Filipino teachers to East Timor to teach English, so as to facilitate a program between the two countries, under which deserving East Timorese nationals with English language skills will be granted university scholarships in the Philippines.[112]

Health

Religion

.jpg)

According to the 2015 census, 97.57% of the population is Roman Catholic; 1.96% Protestant; 0.24% Muslim; 0.08% Traditional; 0.05% Buddhist; 0.02% Hindu, and 0.08% other religions.[1] A 2016 survey conducted by the Demographic and Health Survey programme showed that Catholics made up 98.3% of the population, Protestants 1.2%, and Muslims 0.3%.[113]

The number of churches has grown from 100 in 1974 to over 800 in 1994,[111] with Church membership having grown considerably under Indonesian rule as Pancasila, Indonesia's state ideology, requires all citizens to believe in one God and does not recognise traditional beliefs. East Timorese animist belief systems did not fit with Indonesia's constitutional monotheism, resulting in mass conversions to Christianity. Portuguese clergy were replaced with Indonesian priests and Latin and Portuguese mass was replaced by Indonesian mass.[114] While just 20% of East Timorese called themselves Catholics at the time of the 1975 invasion, the figure surged to reach 95% by the end of the first decade after the invasion.[114][115] In rural areas, Roman Catholicism is syncretised with local animist beliefs.[116] With over 95% Catholic population, East Timor is currently one of the most densely Catholic countries in the world.[117]

The number of Protestants and Muslims declined significantly after September 1999 because these groups were disproportionately represented among supporters of integration with Indonesia and among the Indonesian civil servants assigned to work in the province from other parts of Indonesia, many of whom left the country in 1999.[118] There are also small Protestant and Muslim communities.[118] The Indonesian military forces formerly stationed in the country included a significant number of Protestants, who played a major role in establishing Protestant churches in the territory.[118] Fewer than half of those congregations existed after September 1999, and many Protestants were among those who remained in West Timor.[118] The Assemblies of God is the largest and most active of the Protestant denominations.[118]

While the Constitution of East Timor enshrines the principles of freedom of religion and separation of church and state in Section 45 Comma 1, it also acknowledges "the participation of the Catholic Church in the process of national liberation" in its preamble (although this has no legal value).[119] Upon independence, the country joined the Philippines to become the only two predominantly Roman Catholic states in Asia, although nearby parts of eastern Indonesia such as West Timor and Flores also have Roman Catholic majorities.

The Roman Catholic Church divides East Timor into three dioceses: the Diocese of Díli, the Diocese of Baucau, and the Diocese of Maliana.[120]

Culture

The culture of East Timor reflects numerous influences, including Portuguese, Roman Catholic and Indonesian, on Timor's indigenous Austronesian and Melanesian cultures. East Timorese culture is heavily influenced by Austronesian legends. For example, East Timorese creation myth has it that an ageing crocodile transformed into the island of Timor as part of a debt repayment to a young boy who had helped the crocodile when it was sick.[121][122] As a result, the island is shaped like a crocodile and the boy's descendants are the native East Timorese who inhabit it. The phrase "leaving the crocodile" refers to the pained exile of East Timorese from their island. East Timor is currently finalising its dossiers needed for nominations in the UNESCO World Heritage List, UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists, UNESCO Creative Cities Network, UNESCO Global Geoparks Network, and UNESCO Biosphere Reserve Network. The country currently has one document in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register, namely, On the Birth of a Nation: Turning points.[123]

Arts

There is also a strong tradition of poetry in the country.[124] Prime Minister Xanana Gusmão, for example, is a distinguished poet, earning the moniker "poet warrior".[125]

Architecturally, Portuguese-style buildings can be found, along with the traditional totem houses of the eastern region. These are known as uma lulik ("sacred houses") in Tetum and lee teinu ("legged houses") in Fataluku. Craftsmanship and the weaving of traditional scarves (tais) is also widespread.

An extensive collection of Timorese audiovisual material is held at the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. These holdings have been identified in a document titled The NFSA Timor-Leste Collection Profile, which features catalogue entries and essays for a total of 795 NFSA-held moving image, recorded sound and documentation works that have captured the history and culture of East Timor since the early 20th century.[126] The NFSA is working with the East Timorese government to ensure that all of this material can be used and accessed by the people of that country.[127]

Cinema and TV drama

In 2009 and 2010, East Timor was the setting for the Australian film Balibo and the South Korean film A Barefoot Dream. In 2013, the first East Timorese feature film, Beatriz's War, was released.[128] Two further feature-length films, Abdul & José and Ema Nudar Umanu, were respectively released on 30 July 2017 through the television network of RTTL[129][130] and on 16 August 2018 at the Melbourne International Film Festival.[131] In 2010, the first East Timorese TV drama, Suku Hali was released.

Cuisine

The cuisine of East Timor consists of regional popular foods such as pork, fish, basil, tamarind, legumes, corn, rice, root vegetables, and tropical fruit. East Timorese cuisine has influences from Southeast Asian cuisine and from Portuguese dishes from its colonisation by Portugal. Flavours and ingredients from other former Portuguese colonies can be found due to the centuries-old Portuguese presence on the island. Due to the East and West combination of East Timor's cuisine, it developed features related to Filipino cuisine, which also experienced an East-West culinary combination.

Sports

Sports organisations joined by East Timor include the International Olympic Committee (IOC), the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF), the International Badminton Federation (IBF), the Union Cycliste Internationale, the International Weightlifting Federation, the International Table Tennis Federation (ITTF), the International Basketball Federation (FIBA), and East Timor's national football team joined FIFA. East Timorese athletes competed in the 2003 Southeast Asian Games held 2003. In the 2003 ASEAN Paralympics Games, East Timor won a bronze medal. In the Athens 2004 Olympic Games, East Timorese athletes participated in athletics, weightlifting and boxing. East Timor won three medals in Arnis at the 2005 Southeast Asian Games. East Timor competed in the first Lusophony Games and, in October 2008, the country earned its first international points in a FIFA football match with a 2–2 draw against Cambodia.[132] East Timor competed at the 2014 Winter Olympics.

Thomas Americo was the first East Timorese fighter to fight for a world boxing title. He was murdered in 1999, shortly before the Indonesian occupation of East Timor ended.[133]

See also

- Outline of East Timor

- Index of East Timor-related articles

References

- "Nationality, Citizenship, and Religion". Government of Timor-Leste. 25 October 2015. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Hicks, David (15 September 2014). Rhetoric and the Decolonization and Recolonization of East Timor. Routledge. ISBN 9781317695356 – via Google Books.

- Adelman, Howard (28 June 2011). No Return, No Refuge: Rites and Rights in Minority Repatriation. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231526906 – via Google Books.

- Shoesmith, Dennis (March–April 2003). "Timor-Leste: Divided Leadership in a Semi-Presidential System". Asian Survey. 43 (2): 231–252. doi:10.1525/as.2003.43.2.231. ISSN 0004-4687. OCLC 905451085.

The semi-presidential system in the new state of Timor-Leste has institutionalized a political struggle between the president, Xanana Gusmão, and the prime minister, Mari Alkatiri. This has polarized political alliances and threatens the viability of the new state. This paper explains the ideological divisions and the history of rivalry between these two key political actors. The adoption of Marxism by Fretilin in 1977 led to Gusmão's repudiation of the party in the 1980s and his decision to remove Falintil, the guerrilla movement, from Fretilin control. The power struggle between the two leaders is then examined in the transition to independence. This includes an account of the politicization of the defense and police forces and attempts by Minister of Internal Administration Rogério Lobato to use disaffected Falintil veterans as a counterforce to the Gusmão loyalists in the army. The December 4, 2002, Dili riots are explained in the context of this political struggle.

- Neto, Octávio Amorim; Lobo, Marina Costa (2010). "Between Constitutional Diffusion and Local Politics: Semi-Presidentialism in Portuguese-Speaking Countries" (PDF). APSA 2010 Annual Meeting Paper. SSRN 1644026. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- Beuman, Lydia M. (2016). Political Institutions in East Timor: Semi-Presidentialism and Democratisation. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317362128. LCCN 2015036590. OCLC 983148216. Retrieved 18 August 2017 – via Google Books.

- "East Timor Geography". www.easttimorgovernment.com.

- "Population by Age & Sex". Government of Timor-Leste. 25 October 2015. Archived from the original on 13 November 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". www.imf.org. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- "Human Development Indices and Indicators: 2018 Statistical update" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- "UNGEGN list of country names" (PDF). United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names. 2–6 May 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- "Constituição da República Democrática de Timor" (PDF). Government of Timor-Leste. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Konstituisaun Repúblika Demokrátika Timór-Leste" (PDF). Government of Timor-Leste. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- CIA (29 November 2012). "East and Southeast Asia:Timor-Leste". The World Factbook. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- United Nations General Assembly. "UNANIMOUS ASSEMBLY DECISION MAKES TIMOR-LESTE 191ST UNITED NATIONS MEMBER STATE". United Nations Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. United Nations. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Taylor-Leech, Kerry (2009). "The language situation in Timor-Leste". Current Issues in Language Planning. 10 (1): 1–68. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- East Timor Bid to Join ASEAN Wins 'Strong Support', Bangkok Post, date: 31 January 2011.

- Cavanaugh, Ray (24 April 2019). "Timor-Leste: A young nation with strong faith and heavy burdens". The Catholic World Report.

- Bada, Ferdinand (29 August 2019). "Countries Located Completely in the Southern Hemisphere". www.worldatlas.com.

- "Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste" (PDF). Government of Timor-Leste. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "United Nations Member States". United Nations. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007.

- "European Union deploys Election Observation Mission to Timor Leste". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- "US Department of State: Timor-Leste". State.gov. 20 January 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- "CIA World Factbook". US Govt. 1 July 2014.

- Marwick, Ben; Clarkson, Chris; O'Connor, Sue; Collins, Sophie (December 2016). "Early modern human lithic technology from Jerimalai, East Timor". Journal of Human Evolution (Submitted manuscript). 101: 45–64. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.09.004. PMID 27886810.

- "Lesson 1 (First Part): Population Settlements in East Timor and Indonesia". University of Coimbra. Archived from the original on 2 February 1999.

- "About Timor-Leste > Brief History of Timor-Leste: A History". Timor-Leste.gov.tl. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. 378. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- Pigafetta, Antonio (1969) [1524]. "First voyage round the world". Translated by J.A. Robertson. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild.

- The former sultan of Malacca decided to retake his city from the Portuguese with a fleet of ships from Lusung in 1525 A.D., SOURCE: Barros, Joao de, Decada terciera de Asia de Ioano de Barros dos feitos que os Portugueses fezarao no descubrimiento dos mares e terras de Oriente [1628], Lisbon, 1777, courtesy of William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994, page 194.

- Leibo, Steven (2012), East and Southeast Asia 2012 (45 ed.), Lanham, MD: Stryker Post, pp. 161–165, ISBN 978-1-6104-8885-3

- "Flags of the World". Fotw.net. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "The Portuguese Colonization and the Problem of East Timorese Nationalism". Archived from the original on 23 November 2006.

- Deeley, Neil (2001). The International Boundaries of East Timor. p. 8.

- Schwarz, A. (1994). A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia in the 1990s. Westview Press. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-86373-635-0.

- "Department of Defence (Australia), 2002, "A Short History of East Timor"". Archived from the original on 3 January 2006. Retrieved 3 January 2007. Access date: 3 January 2007.

- Ricklefs, M. C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1300, Second Edition. MacMillan. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-333-57689-2.

- Jardine, pp. 50–51.

- "Official Web Gateway to the Government of Timor-Leste – Districts". Government of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- "The United Nations and Decolonization". www.un.org.

- Benetech Human Rights Data Analysis Group (9 February 2006). "The Profile of Human Rights Violations in Timor-Leste, 1974–1999". A Report to the Commission on Reception, Truth and Reconciliation of Timor-Leste. Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG). pp. 2–4. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012.

- "One Man's Legacy in East Timor". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "UNITED NATIONS TRANSITIONAL ADMINISTRATION IN EAST TIMOR – UNTAET". United Nations. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Etan/Us (15 February 2000). "UN takes over East Timor command". Etan.org. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "Council endorses proposal to declare East Timor's Independence 20 May 2002". United Nations (Press release). Security Council. 31 October 2001. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "East Timor: More than 1,000 refugees return since beginning of month". ReliefWeb. 10 May 2002. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "Constitution of the Democratic Republic of East Timor". refworld. 20 May 2002. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "Unanimous Assembly decision makes Timor-Leste 191st United Nations member state" (Press release). United Nations. 27 September 2002. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- "UN wraps up East Timor mission". ABC News. 30 December 2012.

- "East Timor May Be Becoming Failed State". London. 13 January 2008. Archived from the original on 13 January 2008.

- "Shot East Timor leader 'critical'". BBC News. 11 February 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "The World Heritage Convention has entered into force for Timor-Leste". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 1 February 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- "Diploma Ministerial No:199/GM/MAEOT/IX/09 de 15 de Setembro de 2009 Que fixa o número de Sucos e Aldeias em Território Nacional Exposição de motivos" (PDF), Jornal da Républica, Série I, N.° 33, 16 de Setembro de 2009, 3588-3620, archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2012

- Population and Housing Census 2015, Preliminary Results (PDF), Direcção-Geral de Estatística, retrieved 15 January 2018

- "Lei N.º 3/2014 de 18 de Junho Cria a Região Administrativa Especial de Oe-Cusse Ambeno e estabelece a Zona Especial de Economia Social de Mercado" (PDF), Jornal da República, Série I, N.° 21, 18 de Junho de 2014, 7334-7341

- "East Timor aims to join ASEAN". Investvine. 30 December 2012. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Richard Baker (21 April 2007). "New Timor treaty 'a failure'". Theage.com.au. The Age Company Ltd. Retrieved 3 January 2010.

- "Timor-Leste activists 'shocked' by Australia's prosecution of spy Witness K and lawyer". The Guardian. 21 July 2018.

- "United Nations". United Nations. Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- Exclusive Economic Zones – Sea Around Us Project – Fisheries, Ecosystems & Biodiversity – Data and Visualization.

- "Mount Ramelau". Gunung Bagging. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- "Nino Konis Santana National Park declared as Timor-Leste's (formerly East Timor) first national park". Wildlife Extra.

- Norwegian energy and Water Resources Directorate (NVE) (2004), Iralalaro Hydropower Project Environmental Assessment

- "ReefGIS – Reefs At Risk – Global 1998". Reefgis.reefbase.org. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- de Brouwer, Gordon (2001), Hill, Hal; Saldanha, João M. (eds.), East Timor: Development Challenges For The World's Newest Nation, Canberra, Australia: Asia Pacific Press, pp. 39–51, ISBN 978-0-3339-8716-2

- "Timor-Leste's Economy Remains Strong, Prospects for Private Sector Development Strengthened". Asian Development Bank. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013.

- Schonhardt, Sara (19 April 2012). "Former Army Chief Elected President in East Timor". The New York Times. The New York Times Company.

- "Observers divided over oil fund investment". IRIN Asia. 18 October 2011.

- "Article IV Consultation with the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste". IMF.

- "East Timor axes Australia border treaty over oil reserves". BBC News. BBC UK. 10 January 2017.

- "U.S. Relations With Timor-Leste". U.S. Department of State. 3 July 2012.

- "The Story of East Timorese Coffee". East Timor Now. 16 January 2018.

- "FAOSTAT". faostat3.fao.org.

- "Highlights of the 2010 Census Main Results in Timor-Leste" (PDF). Direcção Nacional de Estatística. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2013.

- "Expanding Timor – Leste's Near – Term Non – Oil Exports" (PDF). World Bank. August 2010. pp. iii.

- "Doing Business in Timor-Leste". World Bank. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "NRI Overall Ranking 2014" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- "TIMOR GAP TREATY between Australia and the Republic of Indonesia ..." Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements Project. Archived from the original on 16 June 2005. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- "The Timor Sea Treaty: Are the Issues Resolved?". Aph.gov.au. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Geoff A. McKee. "McKee: How much is Sunrise really worth?: True Value of a Timor Sea Gas Resource (26 Mar 05)". Canb.auug.org.au. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- "Prime Minister and Cabinet, Timor-Leste Government – Media Releases". Pm.gov.tp. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation (5 December 2013). "East Timor spying case: PM Xanana Gusmao calls for Australia to explain itself over ASIO raids". Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- "Boosting Growth through the Growth Triangle « Government of Timor-Leste". timor-leste.gov.tl.

- "Gazetteer – Patents". Billanderson.com.au. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- "Keine Lust auf Massentourismus? Studie: Die Länder mit den wenigsten Urlaubern der Welt". TRAVELBOOK. 10 September 2018.

- Humanity, Vision of. "Global Peace Index". Vision of Humanity. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Travel Risk Map — International SOS". www.travelriskmap.com. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "East Timor: Administrative Division". City population.

- "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- "Government of Timor-Leste". Timor-leste.gov.tl. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Dickson, Paul (2006). Labels for Locals: What to Call People from Abilene to Zimbabwe. Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-088164-1.

- "The International Thesaurus of Refugee Terminology". UNHCR & FMO. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- "Maubere" article at the German Wikipedia.

- Fox, James J.; Soares, Dionisio Babo (2000). Out of the Ashes: Destruction and Reconstruction of East Timor. C. Hurst. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-85065-554-1.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. Yale University Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- Berlie, Jean A. (2015), "Chinese in East Timor: Identity, Society and Economy", HumaNetten (35): 37–49, doi:10.15626/hn.20153503

- Constâncio Pinto; Matthew Jardine (1997). East Timor's Unfinished Struggle: Inside the East Timorese Resistance. South End Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-89608-541-1.

- Ramos-Horta, J. (20 April 2012). "Timor Leste, Tetum, Portuguese, Bahasa Indonesia or English?". The Jakarta Post.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- "Language", Population and Housing Census of Timor-Leste, 2015, Timor-Leste Ministry of Finance

- Gross, Max L. (14 February 2008). A Muslim Archipelago: Islam and Politics in Southeast Asia: Islam and Politics in Southeast Asia. Government Printing Office. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-16-086920-4. Alt URL

- Paulino, Vicente (2012). "Remembering the Portuguese Presence in Timor and Its Contribution to the Making of Timor's National and Cultural Identity". In Jarnagin, Laura (ed.). Portuguese and Luso-Asian Legacies in Southeast Asia, 1511–2011. 2. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 106. ISBN 978-981-4345-50-7.

- Bivona, Kristal. "East Timor Pumps Up Portuguese". Language Magazine. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- "O estímulo ao uso da língua portuguesa em Timor Leste e Guiné Bissau". Blog of the International Portuguese Language Institute (in Portuguese). 29 May 2015.

- The Impact of the Language Directive on the Courts in East Timor (PDF) (Report). Dili, East Timor: Judicial System Monitoring Programme. August 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- "Estados Membros". União Latina.

- "Languages of East Timor". Ethnologue.

- "Interactive Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". UNESCO.

- "National adult literacy rates (15+), youth literacy rates (15–24) and elderly literacy rates (65+)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

- Roslyn Appleby (30 August 2010). ELT, Gender and International Development: Myths of Progress in a Neocolonial World. Multilingual Matters. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-84769-303-7.

- Robinson, G. If you leave us here, we will die, Princeton University Press 2010, p. 72.

- "Table 5.7 – Profile Of Students That Attended The 2004/05 Academic Year By Rural And Urban Areas And By District". Direcção Nacional de Estatística. Archived from the original on 14 November 2009.

- "Timor-Leste: Demographic and Health Survey, 2016" (PDF). General Directorate of Statistics, Ministry of Planning and Finance & Ministry of Health. p. 35. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. Yale University Press. p. 381. ISBN 978-0-300-10518-6.

- Head, Jonathan (5 April 2005). "East Timor mourns 'catalyst' Pope". BBC News.

- Hajek, John; Tilman, Alexandre Vital (1 October 2001). East Timor Phrasebook. Lonely Planet. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-74059-020-4.

- East Timor slowly rises from the ashes ETAN 21 September 2001 Online at etan.org. Retrieved 22 February 2008

- International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Timor-Leste. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (14 September 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- "Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste" (PDF). Governo de Timor-Leste.

- "Pope Benedict XVI erects new diocese in East Timor". Catholic News Agency.

- Wise, Amanda (2006). Exile and Return Among the East Timorese. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 211–218. ISBN 978-0-8122-3909-6.

- "The Legend and History of Timor Leste", VisitEastTimo

- "Timor-Leste – Memory of the World Register – United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". www.unesco.org.

- "Literatura timorense em língua portuguesa" [Timorese literature in the Portuguese language]. lusofonia.x10.mx (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 29 September 2019.

- "East Timor's president accepts Xanana Gusmao's resignation". ABC News. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

- NFSA provides insight into Timor-Leste history on nfsa.gov.au

- A connection with Timor-Leste on nfsa.gov.au

- "Fresh start for East Timor's film scene". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- "Abdul & José EN (2017)". FIFO Tahiti. Association FIFO. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ETAN; Media ONE Timor (25 July 2017). "The Stolen Child New Documentary". Media ONE Timor. MediaONETimor.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- "Ema Nudar Umanu". MIFF. Melbourne International Film Festival. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- Madra, Ek (30 October 2008). "World's worst football team happy to win first point". Reuters. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- "Thomas Americo – BoxRec". boxrec.com.

Bibliography

- Cashmore, Ellis (1988). Dictionary of Race and Ethnic Relations. New York: Routledge. ASIN B000NPHGX6

- Charny, Israel W. Encyclopedia of Genocide Volume I. Denver: Abc Clio.

- Dunn, James (1996). East Timor: A People Betrayed. Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- Durand, Frédéric (2006). East Timor: A Country at the Crossroads of Asia and the Pacific, a Geo-Historical Atlas. Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books. ISBN 9749575989.

- Groshong, Daniel J (2006). Timor-Leste: Land of Discovery. Hong Kong: Tayo Photo Group. ISBN 988987640X.

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (1999), Timor Loro Sae: 500 years. Macau: Livros do Oriente. ISBN 972-9418-69-1

- Gunn, Geoffrey C (2011). Historical Dictionary of East Timor. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810867543.

- Hägerdal, Hans (2012), Lords of the Land, Lords of the Sea; Conflict and Adaptation in Early Colonial Timor, 1600–1800. Oapen.org

- Kingsbury, Damien; Leach, Michael (2007). East Timor: Beyond Independence. Monash Papers on Southeast Asia, no 65. Clayton, Vic: Monash University Press. ISBN 9781876924492.

- Hill, H; Saldanha, J, eds. (2002). East Timor: Development Challenges for the World's Newest Nation. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-333-98716-2.

- Leach, Michael; Kingsbury, Damien, eds. (2013). The Politics of Timor-Leste: Democratic Consolidation After Intervention. Studies on Southeast Asia, no 59. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, Southeast Asia Program Publications. ISBN 9780877277897.

- Levinson, David. Ethnic Relations. Denver: Abc Clio.

- Molnar, Andrea Katalin (2010). Timor Leste: Politics, History, and Culture. Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia series, 27. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 9780415778862.

- Rudolph, Joseph R. Encyclopedia of Modern Ethnic Conflicts. Westport: Greenwood P, 2003. 101–106.

- Shelton, Dinah. Encyclopedia of Genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. Thompson Gale.

- Taylor, John G. (1999). East Timor: The Price of Freedom. Australia: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-1-85649-840-1.

- Viegas, Susana de Matos; Feijó, Rui Graça, eds. (2017). Transformations in Independent Timor-Leste: Dynamics of Social and Cultural Cohabitations. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781315534992.

- East Timor: a bibliography, a bibliographic reference, Jean A. Berlie, launched by PM Xanana Gusmão, Indes Savantes editor, Paris, France, published in 2001. ISBN 978-2-84654-012-4, ISBN 978-2-84654-012-4.

- East Timor, politics and elections (in Chinese)/ 东帝汶政治与选举 (2001–2006): 国家建设及前景展望, Jean A. Berlie, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies of Jinan University editor, Jinan, China, published in 2007.

- Mats Lundahl and Fredrik Sjöholm. 2019. The Creation of the East Timorese Economy. Springer.

External links

Government

- Timor-Leste official government website

- Timor-Leste official tourism website

- Chief of State and Cabinet Members

General information

- "Timor-Leste". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- East Timor from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Timor-Leste at Curlie

- East Timor at Encyclopædia Britannica

- East Timor profile BBC News

- Key Development Forecasts for Timor-Leste from International Futures

- Timor Leste Studies Association

| Wikibooks Cookbook has a recipe/module on |

.svg.png)