Constitution of Indonesia

The 1945 State Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia (Indonesian: Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945, UUD '45) is the basis for all laws of Indonesia.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Indonesia |

|

|

| 1945 State Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia | |

|---|---|

A 1946 print edition of the constitution | |

| Original title | Undang-Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945 |

| Jurisdiction | |

| Created | 1 June – 18 August 1945 |

| Presented | 18 August 1945 |

| Ratified | 18 August 1945 |

| Date effective | 18 August 1945 |

| System | Unitary Republic |

| Branches | 3 |

| Head of state | President |

| Chambers | Bicameral (People's Consultative Assembly (MPR); divided into two houses: the People's Representative Council (DPR) and the Regional Representative Council (DPD)) |

| Executive | Cabinet led by the President |

| Judiciary | |

| Federalism | Unitary |

| Electoral college | No |

| Entrenchments | 1 |

| First legislature | 29 August 1945 |

| First executive | 18 August 1945 |

| First court | 18 August 1945 |

| Amendments | 4 |

| Last amended | 11 August 2002 |

| Location | National Archives of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia |

| Commissioned by | Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (PPKI) |

| Author(s) | |

| Signatories | All members of Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (PPKI) |

| Media type | Printed text document |

| Supersedes |

|

The constitution was written in June, July, and August 1945, when Indonesia was emerging from Japanese control at the end of World War II. It was abrogated by the Federal Constitution of 1949 and the Provisional Constitution of 1950, but restored on 5 July 1959.

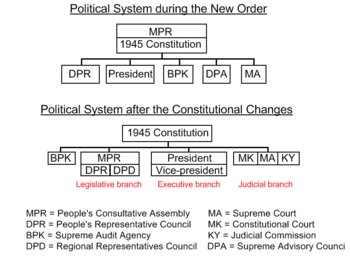

The 1945 Constitution then set forth the Pancasila, the five nationalist principles devised by Sukarno, as the embodiment of basic principles of an independent Indonesian state. It provides for a limited separation of executive, legislative, and judicial powers. The governmental system has been described as "presidential with parliamentary characteristics."[1] Following major upheavals in 1998 and the resignation of President Suharto, several political reforms were set in motion, via amendments to the Constitution, which resulted in changes to all branches of government as well as additional human rights provisions.

History

The writing

The Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies in 1942, defeated the Dutch colonial regime, and occupied it for the duration of World War II. The territory then fell under the jurisdiction of the Japanese Southern Expeditionary Army Group (Nanpo Gun), based in Saigon, Vietnam. The Japanese divided the territory into three military government regions, based on the largest islands: "Sumatra" was under the Japanese 25th Army, "Java" under the Japanese 16th Army and "East Indonesia" (the eastern islands), including part of "Borneo" (Sarawak and Sabah were under the Japanese 38th Army) was under the Imperial Japanese Navy. As the Japanese military position became increasingly untenable, especially after their defeat at the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, more and more native Indonesians were appointed to official positions in the occupation administration.

On 1 March 1945, the 16th Army established the Investigating Committee for Preparatory Work for Independence (Indonesian: Badan Penyelidik Usaha Persiapan Kemerdekaan (BPUPK)), for Java. The 25th Army later established a BPUPK for Sumatra.[2] No such organisation existed for the remainder of Indonesia.

The BPUPK in Java, when established, consisted of 62 members, but there were 68 in the second session. It was chaired by Dr Radjiman Wedyodiningrat (1879–1951). The future president Sukarno and vice-president Mohammad Hatta were among its members. It met in the building that had been used by the Dutch colonial quasi-parliament, the Volksraad ("People's Council") in central Jakarta. It held two sessions, 29 May – 1 June and 10–17 July 1945. The first session discussed general matters, including the philosophy of the state for future independent Indonesia, Pancasila. the philosophy was formulated by nine members of the BPUPK: Sukarno, Hatta, Yamin, Maramis, Soebardjo, Wahid Hasjim, Muzakkir, Agus Salim and Abikoesno.[2] The outcome was something of a compromise, and included an obligation for Muslims to follow Sharia (Islamic law), the so-called Piagam Jakarta (Jakarta Charter) which later changed to the current version of Pancasila. The second session produced a provisional constitution made up of 37 articles, 4 transitory provision and 2 additional provision. The nation would be a unitary state and a republic.

On 26 July 1945, the Allies called for the unconditional surrender of Japan in the Potsdam Declaration. The Japanese authorities, realising they would probably lose the war, began to make firm plans for Indonesian independence, more to spite the Dutch than anything else.[3] On 6 August, an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. On 7 August, the Nanpo Gun headquarters announced that an Indonesian leader could enact a body called the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence (Indonesian: Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (PPKI)). The dropping of a second atomic bomb on Nagasaki, and the Soviet invasion of Manchuria on 9 August prompted the Japanese to surrender unconditionally on 15 August 1945. Sukarno and Hatta declared independence on 17 August 1945, and the PPKI met the following day.[2][4]

In the meeting chaired by Sukarno, the 27 members, including Hatta, Supomo, Wachid Hasjim, Sam Ratulangi and Subardjo, began to discuss the proposed constitution article by article. The Committee made some fundamental changes, including the removal of 7 words from the text of Jakarta Charter which stated the obligation for Muslims to follow Sharia. The new charter then became the preambule of the constitution, and the clause stating that the president must be a Muslim was removed. The historical compromise was made possible in part by the influence of Mohamad Hatta and Tengku Mohamad Hasan. The Committee then officially adopted the Constitution.[2]

Other constitutions

The 1945 Constitution (usually referred to by the Indonesian acronym "UUD'45") remained in force until it was replaced by the Federal Constitution on 27 December 1949. This was in turn replaced by the Provisional Constitution on 17 August 1950. In 1955 elections were held for the People's Representative Council (DPR) as well as for a Constitutional Assembly to draw up a definitive constitution. However, this became bogged down in disputes between nationalists and Islamists, primarily over the role of Islam in Indonesia. Sukarno became increasingly disillusioned by this stagnation and with the support of the military, who saw a much greater constitutional role for themselves, began to push for a return to the 1945 Constitution. This was put to the vote on 30 May 1958 and 2 June 1959, but the motion failed to gain the required two-thirds majority. Finally, on 5 July 1959 President Sukarno issued a decree dissolving the assembly and returning to the 1945 Constitution.[5]

Constitutional amendments

Suharto, who officially became president in 1968, refused to countenance any changes to the Constitution despite the fact that even Sukarno had viewed it as a provisional document.[6] In 1983, the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR) passed a decree stipulating the need for a nationwide referendum to be held before any amendments were made to the Constitution. This led to a 1985 law requiring such a referendum to have a 90% turnout and for any changes to be approved by a 90% vote. Then in 1997, the activist Sri Bintang Pamungkas and two colleagues were arrested and jailed for publishing a proposed modified version of the 1945 Constitution.[7]

With the fall of Suharto and the New Order regime in 1998, the 1983 decree and 1985 law were rescinded and the way was clear to amend the Constitution to make it more democratic. This was done in four stages at sessions of the MPR in 1999, 2000, 2001 and 2002. As a result, the original Constitution has grown from 37 articles to 73, of which only 11% remain unchanged from the original constitution.[8]

The most important of the changes were:[9][10]

- Limiting presidents to two terms of office

- Establishing a Regional Representative Council (DPD), which together with the DPR makes up an entirely elected MPR.

- Purifying and empowering presidential system of government, instead of a semi presidential one.

- Stipulating democratic, direct elections for the president, instead of the president being elected by the MPR

- Reorganizing the mechanism of horizontal relation among state organs, instead of giving the highest constitutional position to the People's Assembly.

- Abolishing the Supreme Advisory Council[11]

- Mandating direct, general, free, secret, honest, and fair elections for the House of Representatives and regional legislatures

- Establishing a Constitutional Court for guarding and defending the constitutional system as set forth in the constitution.

- Establishing a Judicial Commission

- The addition of ten entirely new articles concerning human rights.

Among the above changes, the establishment of Constitutional Court is regarded as a successful innovation in Indonesia constitutional system. The court was established in 2003 by 9 justices head by Professor Jimly Asshiddiqie,a prominent scholar from the University of Indonesia. There are five jurisdictions of the court, i.e. (i) constitutional review of law, (ii) disputes of constitutional jurisdiction between state institutions, (iii) disputes on electoral results, (iv) dissolution of political parties, and (v) impeachment of the president/vice-president. The other icon of success in Indonesian reform is the establishment of the Corruption Eradication Commission which independently fights against corruption and grafts. Corruption in Indonesia is regarded an extraordinary crime.

The legal standing

The 1945 Constitution has the highest legal authority in the country's system of government. The executive, legislative and judicial branches of government must defer to it. The Constitution was originally officially enacted on 18 August 1945. The attached Elucidation, drawn up by Prof. Raden Soepomo (1903–1958), Indonesia's first justice minister, was officially declared to be a part of the Constitution on 5 July 1959. The Preamble, the body of the Constitution and the Elucidation were all reaffirmed as inseparable parts of the Constitution in 1959, and then again in Provisional MPR Decree No. XX/MPRS/1966.[12] However, since the amendments, the Elucidation has not been updated, and still refers to the original document, including parts that have been removed, such as Chapter IV. During the sessions in the People's Assembly, all the ideas setforth in the Elucidation was transformed become articles in the new amendments.[13] Then, final article of the amended Constitution states that the Constitution consists of the Preamble and the articles.[14]

Contents

Preamble

The preamble to the 1945 Constitution of Indonesia contains the Pancasila state philosophy.

Chapter I: Form of state and sovereignty

States that Indonesia is a unitary republic based on law with sovereignty in the hands of the people and exercised through laws.

Chapter II: The People's Consultative Assembly

States that the People's Consultative Assembly is made up of the members of the People's Representative Council and the Regional Representatives Council, all of the members of both bodies being directly elected. The People's Consultative Assembly changes and passes laws, appoints the president, and can only dismiss the president or vice-president during their terms of office according to law.

Chapter III: Executive powers of the state

Outlines the powers of the president. States the requirements for the president and vice-president. Limits the president and vice-president to two terms of office and states that they be elected in a general election. Specifies the impeachment procedure. Includes the wording of the presidential and vice-presidential oath and promise of office.

Chapter IV: Ministers of state

Four short articles giving the cabinet a constitutional basis. The president appoints ministers.

Chapter V: Local government

Explains how Indonesia is divided into provinces, regencies and cities, each with its own administration chosen by general election. The leaders of these administrations are "chosen democratically". Autonomy is applied as widely as possible. The state recognises the special nature of certain regions.

Chapter VI: The People's Representative Council

Its members are elected by general election. It has the right to pass laws, and has legislative, budgeting and oversight functions. It has the right to request government statements and to put forward opinions.

Chapter VII-A: The Regional Representatives Council

An equal number of members is chosen from each province via a general election. The Council can suggest bills related to regional issues to the People's Representative Council. It also advises the House on matters concerning taxes, education and religion.

Chapter VII-B: General elections

General elections to elect the members of the People's Representative Council, the Regional Representatives Council, the president and vice-president and the regional legislatures are free, secret, honest and fair and are held every five years. Candidates for the People's Representative Council and regional legislatures represent political parties: those for the Regional Representatives Council are individuals.

Chapter VIII: Finance

States that the president puts forward the annual state budget for consideration by the People's Representative Council.

Chapter VIII-A: The supreme audit agency

Explains that this exists to oversee the management of state funds. (Cf. Supreme Audit Institution)

Chapter IX: Judicial power

Affirms the independence of the judiciary. Explains the role and position of the Supreme Court as well as the role of the judicial commission. Also states the role of the Constitutional Court.

Chapter IX-A: Geographical extent of the nation

States that the nation is an archipelago whose borders and rights are laid down by law.

Chapter X: Citizens and residents

Defines citizens and residents and states that all citizens are equal before the law. Details the human rights guaranteed to all, including:

- the right of children to grow up free of violence and discrimination

- the right of all to legal certainty

- the right to religious freedom

- the right to choose education, work and citizenship as well as the right to choose where to live

- the right of assembly, association and expression of opinion

- the right to be free from torture

It also states that the rights not to be tortured, to have freedom of thought and conscience, of religion, to not be enslaved, to be recognised as an individual before the law and to not be charged under retroactive legislation cannot be revoked under any circumstances. Furthermore, every person has the right to freedom from discrimination on any grounds whatsoever.

Finally, every person is obliged to respect the rights of others.

Chapter XI: Religion

The nation is based on belief in God, but the state guarantees religious freedom for all.

Chapter XII: National defence

States that all citizens have an obligation and right to participate in the defence of the nation. Outlines the structure and roles of the armed forces and the police.

Chapter XIII: Education and culture

States that every citizen has the right to an education. Also obliges the government to allocate 20 percent of the state budget to education.

Chapter XIV: The national economy and social welfare

States that major means of production are to be controlled by the state. Also states that the state takes care of the poor.

Chapter XV: The flag, language, coat of arms, and national anthem

Specifies the flag, official language, coat of arms, and national anthem of Indonesia.

Chapter XVI: Amendment of the constitution

Lays down the procedures for proposing changes and amending the Constitution. Two-thirds of the members of the People's Consultative Assembly must be present: any proposed amendment requires a simple majority of the entire People's Consultative Assembly membership. The form of the unitary state cannot be changed.

Transitional provisions

States that laws and bodies continue to exist until new ones are specified in this constitution. Calls for the establishment of a Constitutional court before 17 August 2003.

Additional provisions

Tasks the People's Consultative Assembly with re-examining decrees passed by it and its predecessors for their validity to be determined in the 2003 general session.

Notes

- King, Blair A. (30 July 2007). "Constitutional tinkering". Inside Indonesia. Inside Indonesia. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- Kusuma (2004)

- Ricklefs (1982), p. 197

- Ricklefs (1982), pp. 197-198

- Ricklefs (1982), p. 254

- Adnan Buyung Nasution (2001)

- Sri Bintang Pamungkas (1999)

- Denny Indrayana (2008), p331

- Jimly Asshiddiqie (2009)

- Denny Indrayana (2008), pp. 360-381

- Jimly Asshiddiqie (2005)

- Dahlan Thaib (1999)

- Jimly Asshiddiqie(2009)

- Denny Indrayana (2008), pp. 312-313

References

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Adnan Buyung Nasution (2001) The Transition to Democracy: Lessons from the Tragedy of Konstituante in Crafting Indonesian Democracy, Mizan Media Utama, Jakarta, ISBN 979-433-287-9

- Dahlan Thaib, Dr. H, (1999), Teori Hukum dan Konstitusi (Legal and Constitutional Theory), Rajawali Press, Jakarta, ISBN 979-421-674-7

- Denny Indrayana (2008) Indonesian Constitutional Reform 1999-2002: An Evaluation of Constitution-Making in Transition, Kompas Book Publishing, Jakarta ISBN 978-979-709-394-5.

- Jimly Asshiddiqie (2005), Konstitusi dan Konstitutionalisme Indonesia (Indonesia Constitution and Constitutionalism), MKRI, Jakarta.

- Jimly Asshiddiqie (1994), Gagasan Kedaulatan Rakyat dalam Konstitusi dan Pelaksanaannya di Indonesia (The Idea of People's Sovereignty in the Constitution), Ichtiar Baru - van Hoeve, Jakarta, ISBN 979-8276-69-8.

- Jimly Asshiddiqie (2009), The Constitutional Law of Indonesia, Maxwell Asia, Singapore.

- Jimly Asshiddiqie (2005), Hukum Tata Negara dan Pilar-Pilar Demokrasi (Constitutional Law and the Pillars of Democracy), Konpres, Jakarta, ISBN 979-99139-0-X.

- R.M.A.B. Kusuma, (2004) Lahirnya Undang Undang Dasar 1945 (The Birth of the 1945 Constitution),Badan Penerbit Fakultas Hukum Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, ISBN 979-8972-28-7.

- Nadirsyah Hosen, (2007) Shari'a and Constitutional Reform in Indonesia, ISEAS, Singapore

- Saafroedin Bahar,Ananda B.Kusuma,Nannie Hudawati, eds, (1995) Risalah Sidang Badan Penyelidik Usahah Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesian (BPUPKI) Panitia Persiapan Kemerdekaan Indonesia (PPKI) (Minutes of the Meetings of the Agency for Investigating Efforts for the Preparation of Indonesian Independence and the Preparatory Committee for Indonesian Independence), Sekretariat Negara Republik Indonesia, Jakarta

- Sri Bintang Pamungkas (1999), Konstitusi Kita dan Rancangan UUD-1945 Yang Disempurnakan (Our Constitution and a Proposal for an Improved Version of the 1945 Constitution), Partai Uni Demokrasi, Jakarta, No ISBN