Lusitanic

Lusitanic is a term used to refer to persons who share the linguistic and cultural traditions of the Portuguese-speaking nations, territories, and populations, including Portugal, Brazil, Macau, Timor-Leste, Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea Bissau and others, as well as the Portuguese diaspora generally.

The term is derived from Lusitanian ('person of Lusitania', Portuguese: Lusitano, Luso, fem. Lusitana, Lusa; from Latin: Lusitanicus, from Lusitania, the name of a Roman province in the Iberian Peninsula, which encompassed most of modern Portugal).

Luso- is a Late Latin prefix used to denote Portugal/Portuguese, in conjunction with another toponym or demonym.

A Lusophone (Portuguese: Lusófono/a) is someone who speaks the Portuguese language, either natively or as an additional language. As an adjective it means 'Portuguese-speaking'. The Lusosphere or Lusophony (Portuguese: Lusofonia), is the totality of Portuguese speakers around the world, and the influence of the language and culture.

Origin

The term derives from the name of one Ibero-Celtic tribe, the Lusitani, that lived in the north-western part of the Iberian Peninsula prior to the Roman conquest; the lands they inhabited were known as Lusitania. The Lusitani were mentioned for the first time, by Livy in the 1st century BCE, as Carthaginian mercenaries who were incorporated in the army of Hannibal when he fought the Romans.[1] Pliny the Elder states in Naturalis Historia (77–79 CE) that the Lusitanians were Celtiberians in particular, and ancestral to the Celtici of Baetica (now western Andalusia, Spain).[2]

The ultimate etymology of Lusitania, like the origin of the Lusitani who gave the province their name, is unclear. By popular etymology in previous centuries, the name was connected to a supposed Roman demigod Lusus (literally 'Game', a personification of gaming found only in late Roman poetry) combined with an unattested "Celtic" word for 'tribe' or 'region': *Lus- + *-tanus, 'tribe of Lusus'. Others connected Lus- with the Celtic god Lugus.[3]

After the conquest of the peninsula (25–20 BCE), Augustus divided it into the southwestern Hispania Baetica and the western Hispania Lusitania, the latter including the territories of the Celtic tribes known as the Astures (in Asturia) and the Gallaeci (in Gallaecia). In 27 BCE, the Emperor Augustus made a smaller division of the province: Asturia and Gallaecia were ceded to the jurisdiction of the new province Tarraconensis, the former remained as Provincia Lusitania et Vettones. The Roman province of Lusitania comprised what is now central and south Portugal and parts of north-central Spain.

Later Portuguese use of the name Lusitania (and derived words) – primarily figurative, poetic, or historical – is parallel to the use of Gallia in France, Britannia in England, Caledonia in Scotland, Hibernia in Ireland, Batavia in the Netherlands, Helvetia in Switzerland, and Germania and Alemannia in Germany (called Deutschland in its own inhabitants' language). Belgium derived its present name from the Roman Belgica. This attachment to ancient Roman placenames was long used to maintain a "Roman connection" as a means of protecting respectability and legitimacy in political systems dominated by the Roman Catholic church and the (primarily Frankish and later German) Holy Roman Empire, which used Latin as an official language, while Latin remained the written language of the educated class until the early modern era. In the case of Portugal, use of Luso-, Lusitan-, and other such derivatives are attested, for example, in the first Portuguese dictionary, Dictionarium ex Lusitanico in Latinum Sermonem", published in 1569, and the epic poem Os Lusíadas, published in 1572. This sort of connection to Classical Antiquity by use of evocative language saw an increase with the rise of Romanticism in the arts during the 19th century. Another Roman-revival term available to the Portuguese is Iberian and Iberio-, but since it refers to the entire Iberian Peninsula, it is used also by and in reference to the Spanish, and thus is less specific.

Indeed, Portugal was only established as a nation in the 12th Century a. C., with Afonso I of Portugal. After the romanization of the Iberian Peninsula, the area that would become Portugal was conquered by Germanic tribes, then by Umayyads and then reconquered by descendants of the Germanic tribes (see the origins of the Portuguese House of Burgundy). Yet, starting on the 16th century a.C., historians, such as André de Resende, started attempts to weave a story of continuity from the Lusitanians (among the many others who occupied the territory that would later become Portugal) to the Portuguese.[4] It is from this period that the habit of referring to the Portuguese as Lusitanians arises, with the first known reference of the Portuguese as Lusitanians dating from the 15th century, by the Bishop of Évora, Garcia de Meneses.[4]

Broader definitions of Lusitanic or Lusitanian may include medieval-to-modern Galicia, because the Portuguese people and Galician people share close linguistic and cultural ties, including pre-Roman Celtic ones. Modern Portuguese and the Galician language both derive from medieval Galician-Portuguese, and the term is a cultural classification more than a historic–geographical definition. Although, in Ancient Roman times, the Gallaeci were not part of Lusitania province, what became the Galician-Portuguese language developed from Vulgar Latin in Gallaecia, which comprised what is now Galicia, as well as north Portugal, the center of the development of post-Roman Portuguese culture.

Portuguese-speaking countries and regions

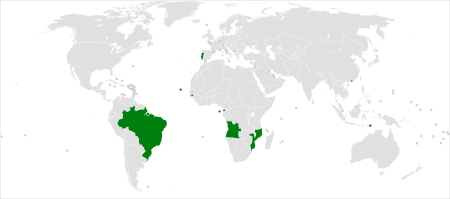

| Portuguese speaking countries |

Lusitanic World |

Portuguese identified as an official or de facto language. |

Today, Portuguese is among the most commonly spoken first languages of the world. During the period of the Portuguese Empire from 1415 to 2002, many people migrated from Portugal to the colonized lands. These settlers brought the Portuguese language, which was the, for the majority of the time, mostly spoken by the government and those of wealth, as the natives, who were generally poor under the regime, retained many of their native languages or created Portuguese Creole Languages.

With the recent fall of the Portuguese Empire, many white Portuguese settlers moved back to Portugal and Portuguese literacy rates dropped. With the establishment of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries and the Instituto Camões, Portuguese has been promoted and special programs have been created to promote Portuguese language and its teaching. Culturally, Portuguese are typically European and are believed to be the one of the longest continuously established population in Europe; they also have small traces of many peoples from the rest of Europe, the Near East and the Mediterranean areas of northern Africa.[5] The Lusitanian countries, including Portugal, are also inhabited by peoples of non-Portuguese ancestry, to widely varying extents.

Language and ethnicities in Portuguese-speaking areas around the world

| Continent/Region | Country/Territory | Languages Spoken [6] | Ethnic Groups [7] | Picture | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | Andorra | Catalan (official) 38.1%, Spanish 39.7%, Portuguese 14.5%, French 8.5% | 36.6% Andorran,33.0% Spanish, 16.3% Portuguese, 6.3% French,7.8% others. | [8][9] | |

| Galicia | Castilian and Galician are the official languages and the languages spoken. Portuguese is observed as a regionally recognised language in some southern isolated areas. | 88% Galician and 12% other Spanish people (9%) and from other countries (3%) |  |

||

| Luxembourg | Luxembourgish (official), French (official), German (official), Portuguese (largest non-official language) | 62% Luxembourger, 38% foreign (over 1/3 of foreign population is Portuguese) | [10] | ||

| Portugal | Portuguese (official), Mirandese (official regional) – (Portuguese is spoken by 100% of the population, over 100% indicates bilingual population). | 96.87% Portuguese and 3.13% legal immigrants (2007) |  |

[11][12] | |

| South America | Brazil | Portuguese (official and most widely spoken language) | white (European ancestry, Ashkenazi Jews, Anusim and Levantine) 53.7%, pardos (brown people, accultured native populations or mixed white, black and/or amerindian, eurasians and gypsies) 38.5%, black 6.2%, other (includes East Asians, South Asians, other Latin Americans, Pacific Islanders and Indigenous Brazilians) 0.9%, unspecified 0.7%. Defined by skin color and not ethnicity. Multiracial people can both self-identify and be accepted as mainly white, black, Asian, Eurasian, Caboclo (meaning Mestizo/Castizo), Gipsy or Amerindian. (2000 census) | .png) |

[13] |

| Africa | Angola | Portuguese (official) – Kikongo, Chokwe, Umbundu, Kimbundu, Ganguela, Kwanyama spoken | Ovimbundu 37%, Kimbundu 25%, Bakongo 13%, mestiço (mixed European and native African) 2%, European 1%, other 22% | [14] | |

| Cape Verde | Portuguese (official) – Cape Verdean Creole (regional) | Creole (mulatto) 71%, African 28%, European 1% |  |

[15] | |

| Equatorial Guinea | Portuguese (official), (Spanish and French are official) | Fang 85.7%, Bubi 6.5%, Mdowe 3.6%, Annobon 1.6%, Bujeba 1.1%, other 1.4% (1994 census) |  |

[16] | |

| Guinea-Bissau | Portuguese (official) – Guinea-Bissau Creole (regional) | African 99% (includes Balanta 30%, Fula 20%, Manjaca 14%, Mandinga 13%, Papel 7%), European and mulatto less than 1% |  |

[17] | |

| Mozambique | Emakhuwa 26.1%, Xichangana 11.3%, Portuguese 8.8% (official; spoken by 27% of population as a second language), Elomwe 7.6%, Cisena 6.8%, Echuwabo 5.8%, other Mozambican languages 32%, other foreign languages 0.3%, unspecified 1.3% (1997 census) | African 99.66% (Makhuwa, Tsonga, Lomwe, Sena, and others), Europeans 0.06%, Euro-Africans 0.2%, Indians 0.08% |  |

[18] | |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | Portuguese (official) | mestiço, angolares (descendants of Angolan slaves), forros (descendants of freed slaves), serviçais (contract laborers from Angola, Mozambique, and Cape Verde), tongas (children of serviçais born on the islands), Europeans (primarily Portuguese) |  |

[19] | |

| Asia | Macau | Portuguese,[20] Cantonese 85.7%, Hokkien 4%, Mandarin 3.2%, other Chinese dialects 2.7%, English 1.5%, Tagalog 1.3%, other 1.6% (2001 census) | Chinese 94.3%, other 5.7% (includes Macanese – mixed Portuguese and Asian ancestry) (2006 census) |  |

[21] |

| East Timor | Tetum (official), Portuguese (official), Indonesian, English | Austronesian (Malayo-Polynesian), Papuan, small Chinese, European (most of Portuguese origin) and mestiço minorities |  |

[22] | |

| Goa | Konkani majority with some Portuguese influence. | Indian | |||

| The CIA World Factbook is in the public domain. Accordingly, it may be copied freely without permission of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).[23] | |||||

Relation to Hispanic and Latino

Lusitanic people have sometimes, especially in the United States, been lumped into the Hispanic label. The term Lusitanic arose because the cultures of Portugal and Spain, and their respective diasporas, though related, are significantly different. Lusitania and the Lusitanians were known long before their conquest by Rome, and their incorporation into the Roman province of Hispania was temporary; both before and after Roman conquest, Lusitania was largely culturally distinct from the rest of Iberia, though the exact geographic center of this culture shifted over time. It is thus argued that Lusitanic people, language, and culture cannot be properly classified as a subset of Hispanic.

In the United States, the term Hispanic was first governmentally adopted by the administration of President Richard Nixon, and today is one of several terms of ethnicity employed to categorize people for various administrative purposes, including census statistics and anti-discrimination laws. The term is defined differently in specific contexts, when defined clearly at all. Most often, it means any person, of any ethnic or racial background(s), of any nationality and of any religion, who has at least one ancestor from the people of Spain. Such a categorization is not exclusive of other ethnicities (one may identify as both European American and Hispanic, as both African American and Hispanic, etc.) In other contexts, it has been used more geographically than ethnically, labeling any person of (or descended from a person of) Spanish-speaking Latin America, whether or not the person has Spanish ancestry (thus including numerous indigenous peoples of the Americas who might otherwise be classified as Native American, if not for the association with Latin American political geography).

Lusitanics are thus not Hispanic for most ethnic categorization purposes in the US, under either definition. However, there are debatably some exceptions. For instance, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission has no official position as to whether or not Lusitanic qualifies as Hispanic,[24] and the State of Florida, for its purposes, classifies Portuguese as Hispanic.[25]

The broader term Latino more often encompasses both Hispanic and Lusitanic.

Lusitanic Americans

Although Portuguese American is more common, the terms Lusitanic American, Lusitanian American (all sometimes hyphenated, especially when used adjectivally), and Luso-American (always hyphenated) are most often used in English to refer to Portuguese-descended people in the United States, and the terms are comparable to African American, Irish American, and similar categorizations. Like all such "hyphenated American" labels, they can be used more broadly to refer to all the Americas generally, and this encompassing sense is more common outside the US. As with the others, more specific national variants exist, e.g. Portuguese Canadian or Luso-Canadian, and Portuguese Brazilian or Luso-Brazilian.

In Brazilian Portuguese, the cognate terms are used with the broad meaning. A Luso-americano (feminine: Luso-americana), with a capital L, is anyone in the Americas with a Portuguese ethnic background. The adjective luso-americano/a (lower case) refers to Portuguese culture in the Western Hemisphere.

With regard to Portuguese culture more broadly: Lusitano/a, or Luso/a for short, defines anyone of Portuguese descent or origin, while lusitano/a is the corresponding cultural adjective; these are equivalent to English Lusitanic. A Lusophone (Lusófono/a) is any speaker of the Portuguese language (more literally in Portuguese a falante português), native or otherwise; lusófono/a is the adjectival form in Portuguese (it usually remains capitalized as Lusophone in English). (Compare Anglophone, Francophone, Hispanophone, for the corresponding terms for use of English, French, and Spanish, respectively.) However, there are various other ways to express "Portuguese-speaking" in Portuguese, varying with context, including de expressão portuguesa and de lingua portuguesa; the expression de língua oficial portuguesa is used of a country (or other entity) that has Portuguese as an official language. The Lusofonia (English: the Lusophony or more commonly the Lusosphere) is the worldwide scope of Portuguese – the influence of the language and culture; its speakers as a group. This is analogous to the English Anglosphere, and the French francophonie (in its broader, non-organizational sense).

The cultural self-identify of the Luso-americano and the concept of an América portuguesa ('Portuguese America') as a distinct, non-Spanish subset of Latin America, independent from Portugal and intrinsically of the Americas, grew out of the Brazilian Independence movement of 1821–25 to establish the Brazilian Empire[26] (a representative parliamentary constitutional monarchy, with widespread freedoms and which eventually abolished slavery). It was usurped in 1889 in a military coup to found the First Brazilian Republic, marked by lesser freedoms than under the monarchy, and replaced in 1930 by the Vargas dictatorship until 1945, liberalized somewhat as the Second Brazilian Republic (or United States of Brazil) until 1964, then overthrown by another totalitarian regime, the Brazilian military government, until 1985, when the modern government of Brazil began, a democratic federative presidential republic, and an emerging world power.

Throughout this sometimes progressive, sometimes regressive, advance from a European colony to a multi-cultural but uniquely Portuguese-American nation-state, there has always remained a tension between Luso-American and Luso-American – that is, between a Euro-centric (in particular, a Portuguese versus Spanish and indigenous) cultural dominance, and a post-Enlightenment, New World distancing from Old World interests and control. While the independence movement was inspired by and learned from the American Revolution, the slave revolt of French Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), and successive waves of break-away republics from Spain in Latin America, the Luso-americano separatist identity dates back to unrest under the European monarchist Old Regime of Portuguese colonial Brazil (compared and related to the French Ancien Régime) of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and has remained integral to socio-political identity as Brazilian up to the present day, distinct not only from European, but from Hispanic-American culture.[26]

See also

- Geographic distribution of the Portuguese language

- Lusophobia

- Lusophony Games

Notes

- Titus Livius Patavinus (Livy). "35.1, et seq.". Ab Urbe Condita Libri. Written ca. 27–9 BCE. Digitized, translated, annotated, and indexed at the Perseus Greco-Roman Collection: Weissenborn, W. (Livy editor); Crane, Gregory R. (editor-in-chief). "Titus Livius (Livy), Ab urbe condita, Index". Perseus Digital Library. Medford, Massachusetts: Tufts University. Retrieved October 18, 2015.

- Pliny the Elder. "3.13". Naturalis Historia.

Celticos a Celtiberis ex Lusitania advenisse manifestum est sacris, lingua, oppidorum vocabulis, quae cognominibus in Baetica distinguntur

Written 77–79 CE. Quoted in: Koch, John T. (2010). "Chapter 9: Paradigm Shift? Interpreting Tartessian as Celtic". In Cunliffe, Barry; Koch, John T. (eds.). Celtic from the West: Alternative Perspectives from Archaeology, Genetics, Language and Literature. Celtic Studies Publications. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp. 292–293. ISBN 978-1-84217-410-4. Reissued in 2012 in softcover as ISBN 978-1-84217-475-3. The text is also found in online sources: , . - Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World. McFarland Inc. p. 228. ISBN 9780786422487.

- Herculano, Alexandre (1846). História de Portugal I - Introdução.

- Estimating the impact of demic diffusion

- CIA World Factbook Language Notes

- CIA World Factbook Ethnicity Notes

- Estadísticas de población de Andorra. Archived 2008-11-18 at the Wayback Machine Ministerio de Justicia e Interior de Andorra

- catala.ad (page 24)

- CIA World Factbook Luxembourg

- INE, Statistics Portugal

- CIA World Factbook Portugal

- CIA World Factbook Brazil

- CIA World Factbook Angola

- CIA World Factbook Cape Verde

- CIA World Factbook Equatorial Guinea

- CIA World Factbook Guinea-Bissau

- CIA World Factbook Mozambique

- CIA World Factbook São Tomé and Príncipe

- www.state.gov

- CIA World Factbook Macau

- CIA World Factbook East Timor

- CIA World Factbook Copyright notice

- Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's position on Lusitanian Archived 2008-09-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Senate of Florida's position on Portuguese as Hispanic

- Garrido Pimenta, João Paolo (May 2006). "Portugueses, americanos, brasileiros: identidades politicas na crise do Antigo Regime luso-americano" [Portuguese, Americans, Brazilians: Political identities during the crises of the Luso-American Ancien Régime] (PDF). Artigos. Almanack Braziliense (in Portuguese). Universidade de São Paulo (3): 69–80. ISSN 1808-8139. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 17, 2007. Retrieved October 18, 2015. The two paragraphs citing this source are essentially a precis of this paper.

External links

- Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa (CPLP) (in Portuguese)

- Sabores da Lusofonia (in Portuguese)

- Portuguese-American Historical & Research Foundation

.png)