Indonesian invasion of East Timor

The Indonesian invasion of East Timor, known in Indonesia as Operation Lotus (Indonesian: Operasi Seroja), began on 7 December 1975 when the Indonesian military invaded East Timor under the pretext of anti-colonialism. The overthrowing of a popular and briefly Fretilin-led government later sparked a violent quarter-century occupation in which between approximately 100,000–180,000 soldiers and civilians are estimated to have been killed or starved to death.[12] The Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor documented a minimum estimate of 102,000 conflict-related deaths in East Timor throughout the entire period 1974 to 1999, including 18,600 violent killings and 84,200 deaths from disease and starvation; Indonesian forces and their auxiliaries combined were responsible for 70% of the killings.[13][14]

| Indonesian invasion of East Timor Operation Lotus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

East Timor dissidents Supported by: |

Supported by: | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Suharto Maraden Panggabean Benny Moerdani Dading Kalbuadi Prabowo Subianto Lopes da Cruz Mario Carrascalão José Osorio Soares |

Francisco Xavier do Amaral Rogério Lobato Nicolau Lobato | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 35,000 soldiers | 2,500 regular troops | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 1,000 injured, captured or dead[10][11] | Unknown | ||||||||

| 100,000 to 180,000 soldiers and civilians dead throughout occupation including between 17,600 and 19,600 violent deaths or disappearances[12] | |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of East Timor |

|

| Chronology |

| Topics |

|

|

During the first months of the occupation, the Indonesian military faced heavy insurgency resistance in the mountainous interior of the island, but from 1977–1978, the military procured new advanced weaponry from the United States, Israel, and other countries, to destroy Fretilin's framework.[15] The last two decades of the century saw continuous clashes between Indonesian and East Timorese groups over the status of East Timor, until 1999, when a majority of East Timorese voted overwhelmingly for independence (the alternative option being "special autonomy" while remaining part of Indonesia). After a further two and a half years of transition under the auspices of three different United Nations missions, East Timor achieved independence on 20 May 2002.[16]

Background

East Timor owes its territorial distinctiveness from the rest of Timor, and the Indonesian archipelago as a whole, to being colonised by the Portuguese, rather than the Dutch; an agreement dividing the island between the two powers was signed in 1915.[17] Colonial rule was replaced by the Japanese during World War II, whose occupation spawned a resistance movement that resulted in the deaths of 60,000 people, 13 percent of the population at the time. Following the war, the Dutch East Indies secured its independence as the Republic of Indonesia and the Portuguese, meanwhile, re-established control over East Timor.

Portuguese withdrawal and civil war

According to the pre-1974 Constitution of Portugal, East Timor, known until then as Portuguese Timor, was an "overseas province", just like any of the provinces outside continental Portugal. "Overseas provinces" also included Angola, Cape Verde, Portuguese Guinea, Mozambique, São Tomé and Príncipe in Africa; Macau in China; and had included the territories of Portuguese India until 1961, when India invaded and annexed the territory.[18]

In April 1974, the left-wing Movimento das Forças Armadas (Armed Forces Movement, MFA) within the Portuguese military mounted a coup d'état against the right-wing authoritarian Estado Novo government in Lisbon (the so-called "Carnation Revolution"), and announced its intention rapidly to withdraw from Portugal's colonial possessions (including Angola, Mozambique and Guinea, where pro-independence guerrilla movements had been fighting since the 1960s).[19]

Unlike the African colonies, East Timor did not experience a war of national liberation. Indigenous political parties rapidly sprang up in Timor: The Timorese Democratic Union (União Democrática Timorense, UDT) was the first political association to be announced after the Carnation Revolution. UDT was originally composed of senior administrative leaders and plantation owners, as well as native tribal leaders.[20] These leaders had conservative origins and showed allegiance to Portugal, but never advocated integration with Indonesia.[21] Meanwhile, Fretilin (the Revolutionary Front of Independent East Timor) was composed of administrators, teachers, and other "newly recruited members of the urban elites."[22] Fretilin quickly became more popular than UDT due to a variety of social programs it introduced to the populace. UDT and Fretilin entered into a coalition by January 1975 with the unified goal of self-determination.[20] This coalition came to represent almost all of the educated sector and the vast majority of the population.[23] The Timorese Popular Democratic Association (Portuguese: Associação Popular Democratica Timorense; APODETI), a third, minor party, also sprang up, and its goal was integration with Indonesia. The party had little popular appeal.[24]

By April 1975, internal conflicts split the UDT leadership, with Lopes da Cruz leading a faction that wanted to abandon Fretilin. Lopes da Cruz was concerned that the radical wing of Fretilin would turn East Timor into a communist front. Fretilin called this accusation an Indonesian conspiracy, as the radical wing did not have a power base.[25] On 11 August, Fretilin received a letter from UDT leaders terminating the coalition.[25]

The UDT coup was a "neat operation", in which a show of force on the streets was followed by the takeover of vital infrastructure, such as radio stations, international communications systems, the airport and police stations.[26] During the resulting civil war, leaders on each side "lost control over the behavior of their supporters", and while leaders of both UDT and Fretilin behaved with restraint, the uncontrollable supporters orchestrated various bloody purges and murders.[27] UDT leaders arrested more than 80 Fretilin members, including future leader Xanana Gusmão. UDT members killed a dozen Fretilin members in four locations. The victims included a founding member of Fretilin, and a brother of its vice-president, Nicolau Lobato. Fretilin responded by appealing successfully to the Portuguese-trained East Timorese military units.[26] UDT's violent takeover thus provoked the three-week long civil war, in pitting its 1,500 troops against the 2,000 regular forces now led by Fretilin commanders. When the Portuguese-trained East Timorese military switched allegiance to Fretilin, it came to be known as Falintil.[28]

By the end of August, the UDT remnants were retreating toward the Indonesian border. A UDT group of nine hundred crossed into West Timor on 24 September 1975, followed by more than a thousand others, leaving Fretilin in control of East Timor for the next three months. The death toll in the civil war reportedly included four hundred people in Dili and possibly sixteen hundred in the hills.[27]

Indonesian motivations

Indonesian nationalist and military hardliners, particularly leaders of the intelligence agency Kopkamtib and special operations unit, Opsus, saw the Portuguese coup as an opportunity for East Timor's annexation by Indonesia.[29] The head of Opsus and close Indonesian President Suharto adviser, Major General Ali Murtopo, and his protege Brigadier General Benny Murdani headed military intelligence operations and spearheaded the Indonesia pro-annexation push.[29] Indonesian domestic political factors in the mid-1970s, were not conducive to such expansionist intentions; the 1974–75 financial scandal surrounding petroleum producer Pertamina meant that Indonesia had to be cautious not to alarm critical foreign donors and bankers. Thus, Suharto was originally not in support of an East Timor invasion.[30]

Such considerations became overshadowed by Indonesian and Western fears that victory for the left-wing Fretilin would lead to the creation of a communist state on Indonesia's border that could be used as a base for incursions by unfriendly powers into Indonesia, and a potential threat to Western submarines. It was also feared that an independent East Timor within the archipelago could inspire secessionist sentiments within Indonesian provinces. These concerns were successfully used to garner support from Western countries keen to maintain good relations with Indonesia, particularly the United States, which at the time was completing its withdrawal from Indochina.[31] The military intelligence organisations initially sought a non-military annexation strategy, intending to use APODETI as its integration vehicle.[29] Indonesia's ruling "New Order" planned for the invasion of East Timor. There was no free expression in "New Order" Indonesia and thus no need was seen for consulting the East Timorese either.[32]

In early September, as many as two hundred special forces troops launched incursions, which were noted by US intelligence, and in October, conventional military assaults followed. Five journalists, known as the Balibo Five, working for Australian news networks were executed by Indonesian troops in the border town of Balibo on 16 October.[33]

Invasion

On 7 December 1975, Indonesian forces invaded East Timor.[34]

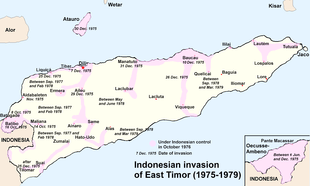

Operasi Seroja (1975–1977)

Operasi Seroja (Operation Lotus) was the largest military operation ever carried out by Indonesia.[35][36] Following a naval bombardment of Dili, Indonesian seaborne troops landed in the city while simultaneously paratroopers descended.[37] 641 Indonesian paratroopers jumped into Dili, where they engaged in six-hours combat with FALINTIL forces. According to author Joseph Nevins, Indonesian warships shelled their own advancing troops and Indonesian transport aircraft dropped some of their paratroopers on top of the retreating Falantil forces and suffered accordingly.[38] By noon, Indonesian forces had taken the city at the cost of 35 Indonesian soldiers killed, while 122 FALINTIL soldiers died in the combat.[39]

On 10 December, a second invasion resulted in the capture of the second biggest town, Baucau, and on Christmas Day, around 10,000 to 15,000 troops landed at Liquisa and Maubara. By April 1976 Indonesia had some 35,000 soldiers in East Timor, with another 10,000 standing by in Indonesian West Timor. A large proportion of these troops were from Indonesia's elite commands. By the end of the year, 10,000 troops occupied Dili and another 20,000 had been deployed throughout East Timor.[40] Massively outnumbered, FALINTIL troops fled to the mountains and continued guerrilla combat operations.[41]

In the cities, Indonesian troops began killing East Timorese.[43] At the start of the occupation, FRETILIN radio sent the following broadcast: "The Indonesian forces are killing indiscriminately. Women and children are being shot in the streets. We are all going to be killed.... This is an appeal for international help. Please do something to stop this invasion."[44] One Timorese refugee told later of "rape [and] cold-blooded assassinations of women and children and Chinese shop owners".[45] Dili's bishop at the time, Martinho da Costa Lopes, said later: "The soldiers who landed started killing everyone they could find. There were many dead bodies in the streets – all we could see were the soldiers killing, killing, killing."[46] In one incident, a group of fifty men, women, and children – including Australian freelance reporter Roger East – were lined up on a cliff outside of Dili and shot, their bodies falling into the sea.[47] Many such massacres took place in Dili, where onlookers were ordered to observe and count aloud as each person was executed.[48] In addition to FRETILIN supporters, Chinese migrants were also singled out for execution; five hundred were killed in the first day alone.[49]

Stalemate

Though the Indonesian military advanced into East Timor, most of the populations left the invaded towns and villages in coastal areas for the mountainous interior. FALINTIL forces, comprising 2,500 full-time regular troops from the former Portuguese colonial army, were well equipped by Portugal and "severely restricted the Indonesian army's ability to make headway."[50] Thus, during the early months of the invasion, Indonesian control was mainly confined to major towns and villages such as Dili, Baucau, Aileu and Same.

Throughout 1976, the Indonesian military used a strategy in which troops attempted to move inland from the coastal areas to join up with troops parachuted further inland. This strategy was unsuccessful and the troops received stiff resistance from Falintil. For instance, it took 3,000 Indonesian troops four months to capture the town of Suai, a southern city only three kilometres from the coast.[51] The military continued to restrict all foreigners and West Timorese from entering East Timor, and Suharto admitted in August 1976 that Fretilin "still possessed some strength here and there."[52]

By April 1977, the Indonesian military faced a stalemate: Troops had not made ground advances for more than six months, and the invasion had attracted increasing adverse international publicity.[53]

Encirclement, annihilation, and final cleansing (1977–1978)

In the early months of 1977, the Indonesian navy ordered missile-firing patrol-boats from the United States, Australia, the Netherlands, South Korea, and Taiwan, as well as submarines from West Germany.[54] In February 1977, Indonesia also received thirteen OV-10 Bronco aircraft from the Rockwell International Corporation with the aid of an official US government foreign military aid sales credit. The Bronco was ideal for the East Timor invasion, as it was specifically designed for counter-insurgency operations in difficult terrain.[7]

By the beginning of February 1977, at least six of the 13 Broncos were operating in East Timor, and helped the Indonesian military pinpoint Fretilin positions.[55] Along with the new weaponry, an additional 10,000 troops were sent in to begin new campaigns that would become known as the 'final solution'.[56]

The 'final solution' campaigns involved two primary tactics: The 'encirclement and annihilation' campaign involved bombing villages and mountain areas from aeroplanes, causing famine and defoliation of ground cover. When surviving villagers came down to lower-lying regions to surrender, the military would simply shoot them. Other survivors were placed in resettlement camps where they were prevented from travelling or cultivating farmland. In early 1978, the entire civilian population of Arsaibai village, near the Indonesian border, was killed for supporting Fretilin after being bombarded and starved.[57] During this period, allegations of Indonesian use of chemical weapons arose, as villagers reported maggots appearing on crops after bombing attacks.[57] The success of the 'encirclement and annihilation' campaign led to the 'final cleansing campaign', in which children and men from resettlement camps would be forced to hold hands and march in front of Indonesian units searching for Fretilin members. When Fretilin members were found, the members would be forced to surrender or to fire on their own people.[58] The Indonesian 'encirclement and annihilation' campaign of 1977–1978 broke the back of the main Fretilin militia and the capable Timorese President and military commander, Nicolau Lobato, was shot and killed by helicopter-borne Indonesian troops on 31 December 1978.[59]

The 1975–1978 period, from the beginning of the invasion to the largely successful conclusion of the encirclement and annihilation campaign, proved to be the toughest period of the entire conflict, costing the Indonesians more than 1,000 fatalities out of the total of 2,000 who died during the entire occupation.[60]

FRETILIN clandestine movement (1980–1999)

The Fretilin militia who survived the Indonesian offensive of the late 1970s chose Xanana Gusmão as their leader. He was caught by Indonesian intelligence near Dili in 1992 and was succeeded by Mau Honi, who was captured in 1993 and in turn, succeeded by Nino Konis Santana. Santana's successor, on his death in an Indonesian ambush in 1998, was by Taur Matan Ruak. By the 1990s, there were approximately fewer than 200 guerilla fighters remaining in the mountains (this lacks citation, it aligns with the common Indonesian view at the time, though Timorese would state a vast amount of the population was actually discreetly involved in the clandestine movement, as ratified in the protest vote for independence), and the separatist idea had largely shifted to the clandestine front in the cities. The clandestine movement was largely paralysed by continuous arrests and infiltration by Indonesian agents. The prospect of independence was very dark until the fall of Suharto in 1998 and President Habibie's sudden decision to allow a referendum in East Timor in 1999.[61]

East Timorese casualties

In March 1976, UDT leader Lopes da Cruz reported that 60,000 Timorese had been killed during the invasion.[62] A delegation of Indonesian relief workers agreed with this statistic.[63] In an interview on 5 April 1977 with the Sydney Morning Herald, Indonesian Foreign Minister Adam Malik said the number of dead was "50,000 people or perhaps 80,000".[42] A figure of 100,000 is cited by McDonald (1980) and by Taylor. Amnesty International estimated that one third of East Timor's population, or 200,000 in total, died from military action, starvation and disease from 1975 to 1999. In 1979 the US Agency for International Development estimated that 300,000 East Timorese had been moved into camps controlled by Indonesian armed forces.[64] The UN's Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor (CAVR) estimated the number of deaths during the occupation from famine and violence to be between 90,800 and 202,600 including between 17,600 and 19,600 violent deaths or disappearances, out of a 1999 population of approximately 823,386. The truth commission held Indonesian forces responsible for about 70% of the violent killings.[65][66][67]

Integration efforts

In parallel to the military action, Indonesia also ran a civil administration. East Timor was given equal status to the other provinces, with an identical government structure. The province was divided into districts, sub districts, and villages along the structure of Javanese villages. By giving traditional tribal leaders positions in this new structure, Indonesia attempted to assimilate the Timorese through patronage.[68]

Though given equal provincial status, in practice East Timor was effectively governed by the Indonesian military.[68] The new administration built new infrastructure and raised productivity levels in commercial farming ventures. Productivity in coffee and cloves doubled, although East Timorese farmers were forced to sell their coffee at low prices to village cooperatives.[69]

The Provisional Government of East Timor was installed in mid-December 1975, consisting of APODETI and UDT leaders. Attempts by the United Nations Secretary General's Special Representative, Vittorio Winspeare Guicciardi to visit Fretilin-held areas from Darwin, Australia were obstructed by the Indonesian military, which blockaded East Timor. On 31 May 1976, a 'People's Assembly' in Dili, selected by Indonesian intelligence, unanimously endorsed an 'Act of Integration', and on 17 July, East Timor officially became the 27th province of the Republic of Indonesia. The occupation of East Timor remained a public issue in many nations, Portugal in particular, and the UN never recognised either the regime installed by the Indonesians or the subsequent annexation.[70]

Justification

The Indonesian government presented its annexation of East Timor as a matter of anticolonial unity. A 1977 booklet from the Indonesian Department of Foreign Affairs, entitled Decolonization in East Timor, paid tribute to the "sacred right of self-determination"[71] and recognised APODETI as the true representatives of the East Timorese majority. It claimed that FRETILIN's popularity was the result of a "policy of threats, blackmail and terror".[72] Later, Indonesian Foreign Minister Ali Alatas reiterated this position in his 2006 memoir The Pebble in the Shoe: The Diplomatic Struggle for East Timor.[73] The island's original division into east and west, Indonesia argued after the invasion, was "the result of colonial oppression" enforced by the Portuguese and Dutch imperial powers. Thus, according to the Indonesian government, its annexation of the 27th province was merely another step in the unification of the archipelago which had begun in the 1940s.[74]

Foreign involvement

There was little resistance from the international community to Indonesia's invasion. Although Portugal was undergoing an energetic decolonization process, Portugal failed to involve the United Nations.[75]

US involvement

For the Ford administration, East Timor was a place of little significance, overshadowed by US–Indonesian relations. The fall of Saigon in mid-1975 had been a devastating setback for the United States, leaving Indonesia as the most important ally in the region. Ford consequently reasoned that the US national interest had to be on the side of Indonesia.[4] As Ford later stated: "in the scope of things, Indonesia wasn't too much on my radar", and "We needed allies after Vietnam".[5]

As early as December 1974—a year before the invasion—the Indonesian defense attaché in Washington sounded out US views about an Indonesian takeover of East Timor.[76] The Americans were tight-lipped, and in March 1975 Secretary of State Henry Kissinger approved a "policy of silence" vis-à-vis Indonesia, a policy that had been recommended by the Ambassador to Indonesia, David Newsom.[77] The administration worried about the potential impact on US–Indonesian relations in the event that a forced incorporation of East Timor was met with a major Congressional reaction.[77] On 8 October 1975, Assistant Secretary of State Philip Habib told meeting participants that "It looks like the Indonesians have begun the attack on Timor." Kissinger's response to Habib was, "I'm assuming you're really going to keep your mouth shut on this subject."[78]

.jpg)

On the day before the invasion, US President Gerald R. Ford and Kissinger met with Indonesian president Suharto. Documents released by the National Security Archive in 2001 revealed that they gave a green light for the invasion.[6] In response to Suharto saying, "We want your understanding if we deem it necessary to take rapid or drastic action [in East Timor]," Ford replied, "We will understand and will not press you on the issue. We understand the problem you have and the intentions you have." Kissinger agreed, although he had fears that the use of US-made arms in the invasion would be exposed to public scrutiny, and Kissinger urged Suharto to wait until Ford had returned from his far eastern trip, because "we would be able to influence the reaction in America if whatever happens happens after we return. This way there would be less chance of people talking in an unauthorised way."[79] The US hoped the invasion would be relatively swift and not involve protracted resistance. "It is important that whatever you do succeeds quickly," Kissinger said to Suharto.[6]

The US played a crucial role in supplying weapons to Indonesia.[4] A week after the invasion of East Timor the National Security Council prepared a detailed analysis of the Indonesian military units involved and the US equipment they used. The analysis revealed that virtually all of the military equipment used in the invasion was US supplied: US-supplied destroyer escorts shelled East Timor as the attack unfolded; Indonesian marines disembarked from US-supplied landing craft; US-supplied C-47 and C-130 aircraft dropped Indonesian paratroops and strafed Dili with .50 calibre machine guns; while the 17th and 18th Airborne brigades which led the assault on the Timorese capital were "totally U.S. MAP supported," and their jump masters US trained.[80] While the US government claimed to have suspended new arms sales to Indonesia from December 1975 to June 1976, military equipment already in the pipeline continued to flow,[6] and the US made four new offers of arms during that six-month period, including supplies and parts for 16 OV-10 Broncos,[6] which, according to Cornell University Professor Benedict Anderson, are "specially designed for counter-insurgency actions against adversaries without effective anti-aircraft weapons and wholly useless for defending Indonesia against a foreign enemy." Military assistance was accelerated during the Carter administration, peaking in 1978.[81] In total, the United States furnished over $250,000,000 of military assistance to Indonesia between 1975 and 1979.[82]

Testifying before the US Congress, the Deputy Legal Advisor of the US State Department, George Aldrich said the Indonesians "were armed roughly 90 percent with our equipment. ... we really did not know very much. Maybe we did not want to know very much but I gather that for a time we did not know." Indonesia was never informed of the supposed US "aid suspension". David T. Kenney, Country Officer for Indonesia in the US State Department, also testified before Congress that one purpose for the arms was "to keep that area [Timor] peaceful."[83]

The CAVR stated in the "Responsibility" chapter of its final report that US "political and military support were fundamental to the Indonesian invasion and occupation" of East Timor between 1975 and 1999. The report (p. 92) also stated that "U.S. supplied weaponry was crucial to Indonesia's capacity to intensify military operations from 1977 in its massive campaigns to destroy the Resistance in which aircraft supplied by the United States played a crucial role."[84][85]

Clinton Administration officials told the New York Times that US support for Suharto was "driven by a potent mix of power politics and emerging markets." Suharto was Washington's favoured ruler of the "ultimate emerging market" who deregulated the economy and opened Indonesia to foreign investors. "He's our kind of guy," said a senior Administration official who dealt often on Asian policy.[86]

Philip Liechty, a senior CIA officer in Indonesia, stated: "I saw intelligence that came from hard, firm sources in East Timor. There were people being herded into school buildings and set on fire. There were people herded into fields and machine-gunned. ... We knew the place was a free-fire zone and that Suharto was given the green light by the United States to do what he did. We sent the Indonesian generals everything that you need to fight a major war against somebody who doesn't have any guns. We sent them rifles, ammunition, mortars, grenades, food, helicopters. You name it; they got it. ... None of that got out in the media. No one gave a damn. It is something that I will be forever ashamed of. The only justification I ever heard for what we were doing was the concern that East Timor was on the verge of being accepted as a new member of the United Nations and there was a chance that the country was going to be either leftist or neutralist and not likely to vote [with the United States] at the UN."[87]

Australian involvement

In September 2000 the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade released previously secret files that showed that comments by the Whitlam Labor Government may have encouraged the Suharto regime to invade East Timor.[88] Despite the unpopularity of the events in East Timor within some segments of the Australian public, the Fraser, Hawke and Keating governments allegedly co-operated with the Indonesian military and President Suharto to obscure details about conditions in East Timor and to preserve Indonesian control of the region.[3] There was some disquiet towards policy with the Australian public, because of the deaths of the Australian journalists and arguably also because the actions of the Timorese people in supporting Australian forces during the Battle of Timor in World War II were well-remembered. Protests took place in Australia against the occupation, and some Australian nationals participated in the resistance movement.

These files from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade also outlined Australian National Security motivations for a Portuguese independent Timor. Repeatedly mentioned in these files are Australian oil interests in Timorese waters; as well as the potential for a renegotiation of the Portuguese Timor sea border North of Australia.[89] In line with these national security interests at the time, department officials saw it as beneficial for Australia to back an Indonesian take over, as opposed to an independent East Timor, stating: "In support of (i), Indonesian absorption of Timor makes geopolitical sense. Any other long-term solution would be potentially disruptive of both Indonesia and the region. It would help confirm our seabed agreement with Indonesia."; they however also stressed the importance of self determination of Portuguese Timor to Australian public pressure.[90] The records available also show that department officials were aware of planned clandestine operations for Indonesia to perform in Portuguese Timor, with the intent being "to ensure that the territory would opt for incorporation into Indonesia."; for which the Indonesians sought support from the Australian government.[91]

Australian governments saw good relations and stability in Indonesia (Australia's largest neighbour) as providing an important security buffer to Australia's north.[92] Nevertheless, Australia provided important sanctuary to East Timorese independence advocates like José Ramos-Horta (who based himself in Australia during his exile). The fall of Suharto and a shift in Australian policy by the Howard Government in 1998 helped precipitate a proposal for a referendum on the question of independence for East Timor.[93] In late 1998, the Australian government drafted a letter to Indonesia setting out a change in Australian policy, suggesting that East Timor be given a chance to vote on independence within a decade. The letter upset Indonesian President B. J. Habibie, who saw it as implying Indonesia was a "colonial power" and he decided to announce a snap referendum.[93] A UN-sponsored referendum held in 1999 showed overwhelming approval for independence, but was followed by violent clashes and a security crisis, instigated by anti-independence militia. Australia then led a United Nations backed International Force for East Timor to end the violence and order was restored. While the intervention was ultimately successful, Australian-Indonesian relations would take several years to recover.[93][94]

UN reaction

On 12 December 1975, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution that "strongly deplored" Indonesia's invasion of East Timor, demanded that Jakarta withdraw troops "without delay" and allow the inhabitants of the island to exercise their right to self-determination. The resolution also requested that the United Nations Security Council take urgent action to protect East Timor's territorial integrity.[95]

On 22 December 1975, the UN Security Council met and unanimously passed a resolution similar to the Assembly's. The Council's resolution called upon the UN Secretary General "to send urgently a special representative to East Timor for the purpose of making on-the-spot assessment of the existing situation and of establishing contact with all parties in the Territory and all States concerned to ensure the implementation of the current resolution.[95]

Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the US ambassador to the UN at the time, wrote in his autobiography that "China altogether backed Fretilin in Timor, and lost. In Spanish Sahara, Russia just as completely backed Algeria, and its front, known as Polisario, and lost. In both instances the United States wished things to turn out as they did, and worked to bring this about. The Department of State desired that the United Nations prove utterly ineffective in whatever measures it undertook. This task was given to me, and I carried it forward with not inconsiderable success."[8] Later, Moynihan admitted that, as US ambassador to the UN, he had defended a "shameless" Cold War policy toward East Timor.

Depictions in fiction

- Balibo, a 2009 Australian film about the Balibo Five, a group of Australian journalists who were captured and killed just prior to the Indonesian invasion of East Timor

- Beatriz's War (A Guerra da Beatriz), a 2013 drama film produced by East Timor set during the Indonesian invasion[96]

See also

- East Timor (province)

Notes

- Indonesia (1977), p. 31.

- "Fed: Cables show Australia knew of Indon invasion of Timor". AAP General News (Australia). 13 September 2000. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- Fernandes, Clinton (2004) Reluctant Saviour: Australia, Indonesia and East Timor

- Simons, p. 189

- Brinkley, Douglas (2007). Gerald R. Ford: The American Presidents Series: The 38th President. p. 132. ISBN 978-1429933414.

- William Burr; Michael Evans, eds. (6 December 2001). "East Timor Revisited: Ford, Kissinger and the Indonesian Invasion, 1975–76". National Security Archive. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Taylor, p. 90

- A Dangerous Place, Little Brown, 1980, p. 247

- Jolliffe, pp. 208–216; Indonesia (1977), p. 37.

- Power Kills R.J. Rummel

- Eckhardt, William, in World Military and Social Expenditures 1987–88 (12th ed., 1987) by Ruth Leger Sivard.

- „Chega!“-Report of Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor (CAVR)

- "Conflict-Related Deaths in Timor-Leste 1974–1999: The Findings of the CAVR Report Chega!" (PDF). Final Report of the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor (CAVR). Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- "Unlawful Killings and Enforced Disappearances" (PDF). Final Report of the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in East Timor (CAVR). p. 6. Retrieved 20 March 2016.

- Taylor, p. 84

- "New country, East Timor, is born; UN, which aided transition, vows continued help" Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. UN News Centre. 19 May 2002. Retrieved on 17 February 2008.

- Ramos-Horta, p. 18

- Ramos-Horta, p. 25

- Ramos-Horta, p. 26

- Taylor (1999), p. 27

- Ramos-Horta, p. 30

- Ramos-Horta, p. 56

- Ramos-Horta, p. 52

- Dunn, p. 6

- Ramos-Horta, p. 53

- Ramos-Horta, p. 54

- Ramos-Horta, p. 55

- Conboy, pp. 209–10

- Schwarz (1994), p. 201.

- Schwarz (1994), p. 208.

- Schwarz (1994), p. 207.

- Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. p. 377. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

- "Eyewitness account of 1975 murder of journalists". Converge.org.nz. 28 April 2000. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- Martin, Ian (2001). Self-determination in East Timor: the United Nations, the ballot, and international intervention. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 16. ISBN 9781588260338.

- Indonesia (1977), p. 39.

- Budiardjo and Liong, p. 22.

- Schwarz (2003), p. 204

- A not-so-distant horror: mass violence in East Timor, By Joseph Nevins, Page 28, Cornell University Press, 2005

- "Angkasa Online". Archived from the original on 20 February 2008.

- Ramos-Horta, pp. 107–08; Budiardjo and Liong, p. 23.

- Dunn (1996), pp. 257–60.

- Quoted in Turner, p. 207.

- Hill, p. 210.

- Quoted in Budiardjo and Liong, p. 15.

- Quoted in Ramos-Horta, p. 108.

- Quoted in Taylor (1991), p. 68.

- Ramos-Horta, pp. 101–02.

- Taylor (1991), p. 68.

- Taylor (1991), p. 69; Dunn (1996), p. 253.

- Taylor, p. 70

- Taylor, p. 71

- "Indonesia admits Fretilin still active," The Times (London), 26 August 1976.

- Taylor, p. 82

- See H. McDonald, Age (Melbourne), 2 February 1977, although Fretilin transmissions did not report their use until 13 May.

- "Big Build-up by Indonesian navy," Canberra Times, 4 February 1977.

- Taylor, p. 91

- Taylor, p. 85

- John Taylor, "Encirclement and Annihilation," in The Spector of Genocide: Mass Murder in the Historical Perspective, ed. Robert Gellately & Ben Kiernan (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 166–67

- Ramos-Horta, Jose (1996) [1987]. Funu: The unfinished saga of East Timor. Lawrenceville NJ: The Red Sea Press. p. 207. ISBN 9780932415158.

- van Klinken, Gerry (October 2005). "Indonesian casualties in East Timor, 1975–1999: Analysis of an official list" (PDF). Indonesia (80): 113. Retrieved 11 June 2012.

- East Timor and Indonesia: The Roots of Violence and Intervention Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- James Dunn cites a study by the Catholic Church suggesting that as many as 60,000 Timorese had been killed by the end of 1976. This figure does not appear to include those killed in the period between the start of the civil war in August 1975 and the invasion on 7 December. See James Dunn, "The Timor Affair in International Perspective", in Carey and Bentley, eds., East Timor at the Crossroads, p. 66

- Taylor (1991), p. 71.

- (Suharto's Indonesia, Blackburn, Australia: Fontana, 1980, p. 215); "East Timor: Contemporary History", in Carey and Bentley, East Timor at the Crossroads, p. 239. McDonald's figure includes the pre-invasion period while Taylor's does not. From National Security Archive – George Washington University

- East Timor population World Bank

- "Chega! The CAVR Report". Archived from the original on 13 May 2012.

- Conflict-Related Deaths In Timor-Leste: 1974–1999 CAVR

- Bertrand, p. 139

- Bertrand, p. 140

- "East Timor UNTAET – Background". Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- Indonesia (1977), p. 16.

- Indonesia (1977), p. 21.

- Alatas, pp. 18–19.

- Indonesia (1977), p. 19.

- Ramos-Horta, p. 57–58

- "Another Meeting with your Indonesian Contacts, Memorandum From W.R. Smyser of the National Security Council Staff to Secretary of State Kissinger". FRUS. 30 December 1974. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- "Policy Regarding Possible Indonesian Military Action against Portuguese Timor, Memorandum From W.R. Smyser of the National Security Council Staff to Secretary of State Kissinger". FRUS. 4 March 1975. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- "Minutes of the Secretary of State's Staff Meeting". FRUS. 8 October 1975. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- "Embassy Jakarta Telegram 1579 to Secretary State [Text of Ford-Kissinger-Suharto Discussion]" (PDF). National Security Archive. 6 December 1975.

- "Indonesian Use of MAP Equipment in Timor, Memorandum from Clinton E. Granger to Brent Scowcroft" (PDF). National Security Council. 12 December 1975.

- "Report: U.S. Arms Transfers to Indonesia 1975–1997". World Policy Institute. March 1997. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- Nunes, Joe (1996). "East Timor: Acceptable Slaughters". The architecture of modern political power.

- The Washington connection and Third World fascism. South End Press. 1979. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-89608-090-4. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

david t. kenney timor peaceful.

- "East Timor truth commission finds U.S. "political and military support were fundamental to the Indonesian invasion and occupation". Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/NSAEBB176/CAVR_responsibility.pdf

- "Real Politics: Why Suharto Is In and Castro Is Out" The New York Times, 31 October 1995

- John Pilger (1999). Hidden Agendas. Vintage. pp. 285–286. ISBN 9781407086415.

- "Fed: Cables show Australia knew of Indon invasion of Timor". AAP General News (Australia). 13 September 2000. Retrieved 3 January 2008.

- "Volume 20: Australia and the Indonesian Incorporation of Portuguese Timor, 1974-1976". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia).

- "Letter from McCredie to Feakes". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia).

- "Letter from Furlonger to Feakes". Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Australia).

- "In office". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- "The Howard Years: Episode 2: "Whatever It Takes"". Program Transcript. Australian Broadcasting Commission. 24 November 2008. Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=robert_cribb

- Nevins, p. 70

- "A Guerra da Beatriz".

Bibliography

- Bertrand, Jacques (2004). Nationalism and Ethnic Conflict in Indonesia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52441-5.

- Dunn, James (1996). Timor: A People Betrayed. ISBN 0-7333-0537-7.

- Emmerson, Donald, ed. (1999). Indonesia Beyond Suharto. East Gate Books. ISBN 1-56324-889-1.

- Gellately, Robert; Kiernan, Ben, eds. (2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in the Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52750-3.

- Nevins, Joseph (2005). A Not-So-Distant Horror: Mass Violence in East Timor. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8984-6.

- Ramos-Horta, Jose (1987). Funu: The Unfinished Saga of East Timor. Red Sea Press. ISBN 0-932415-14-8.

- Schwarz, A. (1994). A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia in the 1990s. Westview Press. ISBN 1-86373-635-2.

- Simons, Geoff (2000). Indonesia: The Long Oppression. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-22982-8.

- Taylor, John G. (1999). East Timor: The Price of Freedom. Zed Books. ISBN 1-85649-840-9.

- Taylor, John G. (1991). Indonesia's Forgotten War: The Hidden History of East Timor. London: Zed Books. updated and released in late 1999 as East Timor: The Price of Freedom

- Indonesia. Department of Foreign Affairs. Decolonization in East Timor. Jakarta: Department of Information, Republic of Indonesia, 1977. OCLC 4458152.

Further reading

- Indonesian Casualties in East Timor, 1975–1999: Analysis of an Official List

- Gendercide Watch. Case Study: East Timor (1975–99)

- History of East Timor – Indonesia Invades

- USING ATROCITIES: U.S. Responsibility for the SLAUGHTERS IN INDONESIA and EAST TIMOR by Peter Dale Scott, PhD

- War, Genocide, and Resistance in East Timor, 1975–99: Comparative Reflections on Cambodia by Ben Kiernan

- Historical Dictionary of East Timor by Geoffrey C. Gunn