Portuguese Macau

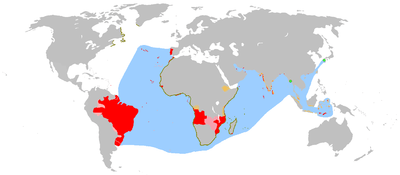

Portuguese Macau covers Macau's history from the establishment of a Portuguese settlement in 1557 to the end of colonial rule in 1999. Macau was both the first and last European holding in China.[2]

Macau 澳門 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1557–1999 | |||||||||

Anthem: Hymno Patriótico (1809–1834) "Patriotic Anthem" Hino da Carta (1834–1910) "Hymn of the Charter" A Portuguesa (1910–1999) "The Portuguese" | |||||||||

.png) | |||||||||

| Status | De facto Portuguese settlement (1557–1887) Official Portuguese colony (1887–1999) | ||||||||

| Official languages | Portuguese Chinese1 | ||||||||

| Religion | Christianity (Roman Catholicism), Buddhism, Chinese folk religion | ||||||||

| Government | Mixed government | ||||||||

| Head of state | |||||||||

• 1887–1889 (first) | King Luís I | ||||||||

• 1996–1999 (last) | President Jorge Sampaio | ||||||||

| Captain-Major/Governor | |||||||||

• 1557–1558 (first) | Francisco Martins | ||||||||

• 1991–1999 (last) | Vasco Rocha Vieira | ||||||||

| Legislature | Senate (1583–1849) Legislative Assembly (1976–1999) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Portuguese discoveries to 20th century | ||||||||

• Portuguese settlement established | 1557 | ||||||||

| 1 December 1887 | |||||||||

| 20 December 1999 | |||||||||

| Currency | Macanese pataca (1894–1999) | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | MO | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | China (Macau) | ||||||||

Overview

Macau's history under Portugal can be broadly divided into three distinct political periods.[3] The first was the establishment of the Portuguese settlement in 1557 until 1849.[4] There was a system of mixed jurisdiction; the Portuguese had jurisdiction over the Portuguese community and certain aspects of the territory's administration but had no real sovereignty.[3] The second was the colonial period, which scholars generally place from 1849 to 1974.[5] As Macau's importance among other territories grew within the Portuguese Empire, Portuguese sovereignty over Macau was strengthened and it became a constitutional part of Portuguese territory.[3] Chinese sovereignty during this era was mainly nominal.[5] Finally, the third was the transition period or post-colonial period, which occurred after the Carnation Revolution in 1974 until the handover in 1999.[3][6]

Wu Zhiliang more specifically identified six periods:[7]

- The early relationship between the Chinese and Portuguese (1514–1583)

- The Senado (Senate) period (1583–1783)

- The decline of the Senado (1783–1849)

- The colonial period (1849–1976)

- The district autonomy period (1976–1988)

- The transition period (1988–1999)

History

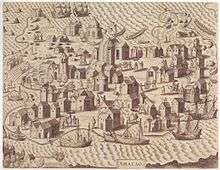

The use of Macau as a commercial port dates back to 1535 during the Ming dynasty, when local authorities established a custom house, collecting 20,000 taels in annual custom duties.[8] Sources also call this payment a rent or bribe.[9] In 1554, the custom house was moved to Lampacao likely due to threats of piracy.[8] After the Portuguese helped the Chinese defeat the pirates, they were allowed to settle in Macau.[8][10] By 1557, they established a permanent settlement,[11] paying an annual ground rent of 500 taels.[12] In 1573, the Chinese built the Barrier Gate to regulate traffic and trade. The rent and boundary delimitation showed both the Portuguese subsidiary position to the Ming government and China's tacit acceptance of Macau's de facto foreign occupation. By 1583, the enclave had a municipal government with a Senate Council.[11]

The Kingdom of Portugal declared a right of sovereignty over Macau in 1783.[13] The 1822 constitution included Macau as an integral part of its territory.[3] A Portuguese royal decree on 20 November 1845 declared Macau a free port.[14] In 1846, Ferreira do Amaral was appointed governor, having been given a mandate to assert Portuguese sovereignty. He terminated the rent, closed the custom house headed by the hoppo, imposed taxes on the Chinese residents, and placed them under Portuguese law.[4] The Senate opposed his actions, stating that establishing full control by force was an "unfair and disloyal gesture".[15] Amaral dissolved the Senate and called them unpatriotic. He told Chinese officials that they would be received as representatives of a foreign power. Amaral's policies evoked much resentment, and he was assassinated by Chinese men on 22 August 1849. This led the Portuguese to capture the Passaleão fort beyond the Barrier Gate three days later.[15]

On 26 March 1887, the Lisbon Protocol was signed, in which China recognised the "perpetual occupation and government of Macao" by Portugal who in turn, agreed never to surrender Macau to a third party without Chinese agreement.[16] This was reaffirmed in the Treaty of Peking on 1 December.[16] A growing nationalist movement in China voiced disapproval of the treaty and questioned its validity. Although the Nationalist (Kuomintang) government in China vowed to abrogate the "unequal treaties", Macau's status remained unchanged. The 1928 Sino-Portuguese Treaty of Friendship and Trade reaffirmed Portuguese administration over Macau.[17] In 1945, after the end of extraterritorial rights in China, the Nationalists called for the liquidation of foreign control over Hong Kong and Macau, but they were too preoccupied in the civil war with the Communists to fulfil their goals.[18]

After the 1974 revolution in Portugal, a new decolonisation policy paved the way for Macau's retrocession to the People's Republic of China (PRC).[17] Portugal offered to withdraw from Macau in late 1974, but China declined in favour of a later time because it sought to preserve international and local confidence in Hong Kong, which was still under British rule. In January 1975, Portugal recognised the PRC as the sole government of China.[17][19] On 17 February 1976, the Portuguese parliament passed the Organic Statute of Macau, which called it a "territory under Portuguese administration". This term was also put in Portugal's 1976 constitution, replacing Macau's designation as an overseas province. Unlike previous constitutions, Macau was not included as an integral part of Portuguese territory.[6] The 1987 Sino-Portuguese Joint Declaration called Macau a "Chinese territory under Portuguese administration". Full sovereignty was transferred in a ceremony on 20 December 1999.[20]

Government

Since 1657, the office of Captain-Major was appointed by the King of Portugal or on his behalf by the Viceroy of India to any fidalgo (nobleman) or gentleman who excelled in services to the Crown.[21] The Captain-Major was head of the fleets and emporia from Malacca to Japan, and the official representative of Portugal to Japan and China. Since he was often away from Macau for long periods, an embryonic municipal government formed in 1560 to resolve matters. Three representatives chosen by vote held the title of eleitos (elected) and could perform administrative and judicial duties.[22]

By 1583, the Senate Council was formed, later called the Loyal Senate (Leal Senado).[11] It consisted of three aldermen, two judges, and one city procurator.[22] Portuguese citizens in Macau elected six electors who would then select the senators.[23] The most serious issues were dealt with by convening the General Council of Ecclesiastic Authorities and leading citizens to decide what measures should be taken.[22] After several Dutch invasions, the Senate created the post of War Governor in 1615 to establish a permanent presence of a military commander.[24] In 1623, the Viceroy created the office of Governor and Captain-General of Macau, replacing the Captain-Major's authority over the territory.[25][26]

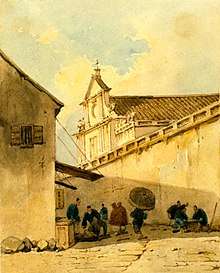

Macau was originally administered as part of Xiangshan County, Guangdong. Chinese and Portuguese officials discussed affairs in casa da câmara, or the city hall, where the Leal Senado Building was later built. In 1731, the Chinese set up an assistant magistrate (xian cheng) in Qian Shan Zhai to manage affairs in Macau. In 1743, he was later based in Mong Ha village (Wang Xia), now part of Our Lady of Fátima, Macau. In 1744, the Chinese formed the Macau Coast Military and Civilian Government headed by a subprefect (tongzhi) based in Qian Shan Zhai.[27]

Sovereignty

The sovereignty over Macau has been a complex issue. Professor of Sociology, Zhidong Hao, at the University of Macau said that some consider sovereignty to be "absolute" and cannot be shared, while others say it is "relative" and can be joint or shared.[7] He stated:

The complexity of the sovereignty question in Macau suggests that the Chinese and Portuguese shared Macau's sovereignty before 1999. [...] In the colonial period of Macau, China had the lesser control in Macau, therefore the lesser sovereignty, and Portugal had more of it. On the other hand, if the Portuguese had sovereignty over Macau, even after the 1887 treaty, it was never absolute either. So sovereignty in fact had been shared between China and Portugal in one way or another, with one party having more at one time than the other.[7]

Macau's political status was still disputed after the 1887 treaty due to its ambiguous wording. The interpretation depends on the perspective of the writer, with the Portuguese and Chinese taking different sides. Scholar Paulo Cardinal, who has been a legal advisor to the Legislative Assembly of Macau, wrote:

On an international law level of analysis, Macau has been characterized by western scholars as a territory on a lease; a union community with Portugal enshrined in and by the Chief of State; a condominium; a territory under an internationalized regime; a territory under a special situation; an autonomous territory without integration connected to a special international situation; and a dependent community subjected to a dual distribution of sovereignty powers (in other words, China held the sovereignty right but Portugal was responsible for its exercise). Without a doubt, it was an atypical situation. Since the Joint Declaration, Macau was, until 19 December 1999, an internationalized territory by international law standards, despite the absence of such a label in the treaty itself.[28]

Gallery

See also

- Military of Macau under Portuguese rule

- China–Portugal relations

- Portuguese Empire

- Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (archives in Lisbon documenting the Portuguese Empire, including Macau)

- British Hong Kong

- Guangzhouwan (1898–1945), French leased territory in China administered as part of Indochina

- British Weihaiwei (1898–1930)

References

- Yee, Herbert S. (2001). Macau in Transition: From Colony to Autonomous Region. Hampshire: Palgrave. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-230-59936-9.

- Dillon, Michael (2017). Encyclopedia of Chinese History. New York: Routledge. p. 418. ISBN 978-1-315-81853-5.

- Cardinal 2009, p. 225

- Halis 2015, pp. 70–71

- Hao 2011, p. 40

- Halis 2015, pp. 72–73

- Hao 2011, pp. 31–32, 224

- Chang, T'ien-Tse (1933). Sino-Portuguese Trade from 1514 to 1644: A Synthesis of Portuguese and Chinese Sources. Leyden: E. J. Brill. p. 93.

- Strauss, Michael J. (2015). Territorial Leasing in Diplomacy and International Law. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff. p. 58. ISBN 978-90-04-29362-5.

- Rêgo, António da Silva (1994). "Direct Sailings Between Macao and Brazil: An Unrealizable Dream? (1717-1810)". Review of Culture. No. 22 (2nd series). Cultural Institute of Macao.

- Mendes 2013, p. 10

- Twitchett, Denis; Mote, Frederick W., eds. (1998). The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 344. ISBN 0-521-24333-5.

- Mendes 2013, p. 7

- Sena, Tereza (2008). "Macau's Autonomy in Portuguese Historiography (19th and early 20th centuries)". Bulletin of Portuguese/Japanese Studies 17: 91–92.

- Hao 2011, pp. 41–42

- Mayers, William Frederick (1902). Treaties Between the Empire of China and Foreign Powers (4th ed.). Shanghai: North-China Herald. pp. 156–157.

- Chan, Ming K. (2003). "Different Roads to Home: The Retrocession of Hong Kong and Macau to Chinese Sovereignty". Journal of Contemporary China 12 (36): 497–499.

- Cohen, Jerome Alan; Chiu, Hungdah (2017) [1974]. People's China and International Law: A Documentary Study. Vol. 1. Princeton University Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-691-61869-2.

- Chan, Ming K.; Chan, Shiu-hing Lo (2006). The A to Z of the Hong Kong SAR and the Macao SAR. Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. pp. 283–284. ISBN 978-0-8108-7633-0.

- Cardinal 2009, p. 228

- Fei 1996, p. 25

- Gomes, Luís Gonzaga (1995). "Summary of the History of Macao". No. 23 (2nd series). Cultural Institute of Macao.

- Fei 1996, p. 36

- Cardinal, Paulo (2007). "Macau: The Internationalization of an Historical Autonomy". In Practising Self-Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-1-107-01858-7.

- Alberts, Tara (2016). "Colonial Conflicts: Factional Disputes in Two Portuguese Settlements in Asia". In Cultures of Conflict Resolution in Early Modern Europe. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781472411556.

- Hao 2011, p. 33

- Hao 2011, pp. 35–36

- Cardinal 2009, p. 226

Bibliography

- Cardinal, Paulo (2009). "The Judicial Guarantees of Fundamental Rights in the Macau Legal System". In One Country, Two Systems, Three Legal Orders - Perspectives of Evolution: Essays on Macau's Autonomy After the Resumption of Sovereignty by China. Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-68572-2.

- Fei, Chengkang (1996). Macao 400 Years. Translated by Wang Yintong and Sarah K. Schneewind. Shanghai: Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences.

- Halis, Denis de Castro (2015). "'Post-Colonial' Legal Interpretation in Macau, China: Between European and Chinese Influences". In East Asia's Renewed Respect for the Rule of Law in the 21st Century. Leiden: Brill Nijhoff. ISBN 978-90-04-27420-4.

- Hao, Zhidong (2011). Macao History and Society. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-988-8028-54-2.

- Mendes, Carmen Amado (2013). Portugal, China and the Macau Negotiations, 1986–1999. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-988-8139-00-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portuguese Macau. |

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (1996). Encountering Macau, A Portuguese City-State on the Periphery of China, 1557–1999. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-8970-4.

- Official website of the Portuguese Government of Macau (Web archive) (in Portuguese) (1999)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)