Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a country situated in the confluence of Western, Central, and Southern Europe.[12][note 4] It is a federal republic composed of 26 cantons, with federal authorities based in Bern.[1][2][note 1] Switzerland is a landlocked country bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. It is geographically divided among the Swiss Plateau, the Alps, and the Jura, spanning a total area of 41,285 km2 (15,940 sq mi), and land area of 39,997 km2 (15,443 sq mi). While the Alps occupy the greater part of the territory, the Swiss population of approximately 8.5 million is concentrated mostly on the plateau, where the largest cities and economic centres are located, among them Zürich, Geneva and Basel, where multiple international organisations are domiciled (such as FIFA, the UN's second-largest Office, and the Bank for International Settlements) and where the main international airports of Switzerland are.

Swiss Confederation | |

|---|---|

Anthem: "Swiss Psalm" | |

| |

| Capital | None (de jure) Bern (de facto)[note 1][1][2] 46°57′N 7°27′E |

| Largest city | Zürich |

| Official languages | German French Italian Romansh |

| Religion (2018[3]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | English: Swiss, German: Schweizer(in), French: Suisse(sse), Italian: svizzero/svizzera, or elvetico/elvetica, Romansh: Svizzer/Svizra |

| Government | Federal semi-direct democracy under a multi-party assembly-independent[4][5] directorial republic |

• Federal Council | |

• Federal Chancellor | Walter Thurnherr |

| Legislature | Federal Assembly |

| Council of States | |

| National Council | |

| History | |

• Foundation date | c. 1300[note 2] (traditionally 1 August 1291) |

| 24 October 1648 | |

• Restoration | 7 August 1815 |

| 12 September 1848[note 3][6] | |

| Area | |

• Total | 41,285 km2 (15,940 sq mi) (132nd) |

• Water (%) | 4.2 |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | |

• 2015 census | 8,327,126[8] |

• Density | 207/km2 (536.1/sq mi) (48th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2018) | low · 19th |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 2nd |

| Currency | Swiss franc (CHF) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy (AD) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +41 |

| ISO 3166 code | CH |

| Internet TLD | .ch, .swiss |

The establishment of the Old Swiss Confederacy dates to the late medieval period, resulting from a series of military successes against Austria and Burgundy. Swiss independence from the Holy Roman Empire was formally recognized in the Peace of Westphalia in 1648. The Federal Charter of 1291 is considered the founding document of Switzerland which is celebrated on Swiss National Day. Since the Reformation of the 16th century, Switzerland has maintained a strong policy of armed neutrality; it has not fought an international war since 1815 and did not join the United Nations until 2002. Nevertheless, it pursues an active foreign policy and is frequently involved in peace-building processes around the world.[13] Switzerland is the birthplace of the Red Cross, one of the world's oldest and best known humanitarian organisations, and is home to numerous international organisations, including the United Nations Office at Geneva, which is its second-largest in the world. It is a founding member of the European Free Trade Association, but notably not part of the European Union, the European Economic Area or the Eurozone. However, it participates in the Schengen Area and the European Single Market through bilateral treaties.

Switzerland occupies the crossroads of Germanic and Romance Europe, as reflected in its four main linguistic and cultural regions: German, French, Italian and Romansh. Although the majority of the population are German-speaking, Swiss national identity is rooted in a common historical background, shared values such as federalism and direct democracy,[14] and Alpine symbolism.[15][16] Due to its linguistic diversity, Switzerland is known by a variety of native names: Schweiz [ˈʃvaɪts] (German);[note 5] Suisse [sɥis(ə)] (French); Svizzera [ˈzvittsera] (Italian); and Svizra [ˈʒviːtsrɐ, ˈʒviːtsʁɐ] (Romansh).[note 6] On coins and stamps, the Latin name, Confoederatio Helvetica – frequently shortened to "Helvetia" – is used instead of the four national languages.

The sovereign state is one of the most developed countries in the world, with the highest nominal wealth per adult[17] and the eighth-highest per capita gross domestic product.[18][19] It ranks at or near the top in several international metrics, including economic competitiveness and human development. Zürich, Geneva and Basel have been ranked among the top ten cities in the world in terms of quality of life, with Zürich ranked second globally.[20] In 2019, IMD placed Switzerland first in attracting skilled workers.[21] World Economic Forum ranks it the 5th most competitive country globally.[22]

Etymology

The English name Switzerland is a compound containing Switzer, an obsolete term for the Swiss, which was in use during the 16th to 19th centuries.[23] The English adjective Swiss is a loan from French Suisse, also in use since the 16th century. The name Switzer is from the Alemannic Schwiizer, in origin an inhabitant of Schwyz and its associated territory, one of the Waldstätte cantons which formed the nucleus of the Old Swiss Confederacy. The Swiss began to adopt the name for themselves after the Swabian War of 1499, used alongside the term for "Confederates", Eidgenossen (literally: comrades by oath), used since the 14th century. The data code for Switzerland, CH, is derived from Latin Confoederatio Helvetica (English: Helvetic Confederation).

The toponym Schwyz itself was first attested in 972, as Old High German Suittes, ultimately perhaps related to swedan ‘to burn’ (cf. Old Norse svíða ‘to singe, burn’), referring to the area of forest that was burned and cleared to build.[24] The name was extended to the area dominated by the canton, and after the Swabian War of 1499 gradually came to be used for the entire Confederation.[25][26] The Swiss German name of the country, Schwiiz, is homophonous to that of the canton and the settlement, but distinguished by the use of the definite article (d'Schwiiz for the Confederation,[27] but simply Schwyz for the canton and the town).[28] The long [iː] of Swiss German is historically and still often today spelled ⟨y⟩ rather than ⟨ii⟩, preserving the original identity of the two names even in writing.

The Latin name Confoederatio Helvetica was neologized and introduced gradually after the formation of the federal state in 1848, harking back to the Napoleonic Helvetic Republic, appearing on coins from 1879, inscribed on the Federal Palace in 1902 and after 1948 used in the official seal.[29] (for example, the ISO banking code "CHF" for the Swiss franc, and the country top-level domain ".ch", are both taken from the state's Latin name). Helvetica is derived from the Helvetii, a Gaulish tribe living on the Swiss plateau before the Roman era.

Helvetia appears as a national personification of the Swiss confederacy in the 17th century with a 1672 play by Johann Caspar Weissenbach.[30]

History

Switzerland has existed as a state in its present form since the adoption of the Swiss Federal Constitution in 1848. The precursors of Switzerland established a protective alliance at the end of the 13th century (1291), forming a loose confederation of states which persisted for centuries.

Early history

The oldest traces of hominid existence in Switzerland date back about 150,000 years.[31] The oldest known farming settlements in Switzerland, which were found at Gächlingen, have been dated to around 5300 BC.[31]

The earliest known cultural tribes of the area were members of the Hallstatt and La Tène cultures, named after the archaeological site of La Tène on the north side of Lake Neuchâtel. La Tène culture developed and flourished during the late Iron Age from around 450 BC,[31] possibly under some influence from the Greek and Etruscan civilisations. One of the most important tribal groups in the Swiss region was the Helvetii. Steadily harassed by the Germanic tribes, in 58 BC the Helvetii decided to abandon the Swiss plateau and migrate to western Gallia, but Julius Caesar's armies pursued and defeated them at the Battle of Bibracte, in today's eastern France, forcing the tribe to move back to its original homeland.[31] In 15 BC, Tiberius, who would one day become the second Roman emperor, and his brother Drusus, conquered the Alps, integrating them into the Roman Empire. The area occupied by the Helvetii—the namesakes of the later Confoederatio Helvetica—first became part of Rome's Gallia Belgica province and then of its Germania Superior province, while the eastern portion of modern Switzerland was integrated into the Roman province of Raetia. Sometime around the start of the Common Era, the Romans maintained a large legionary camp called Vindonissa, now a ruin at the confluence of the Aare and Reuss rivers, near the town of Windisch, an outskirt of Brugg.

The first and second century AD was an age of prosperity for the population living on the Swiss plateau. Several towns, like Aventicum, Iulia Equestris and Augusta Raurica, reached a remarkable size, while hundreds of agricultural estates (Villae rusticae) were founded in the countryside.

Around 260 AD, the fall of the Agri Decumates territory north of the Rhine transformed today's Switzerland into a frontier land of the Empire. Repeated raids by the Alamanni tribes provoked the ruin of the Roman towns and economy, forcing the population to find shelter near Roman fortresses, like the Castrum Rauracense near Augusta Raurica. The Empire built another line of defence at the north border (the so-called Donau-Iller-Rhine-Limes), but at the end of the fourth century the increased Germanic pressure forced the Romans to abandon the linear defence concept, and the Swiss plateau was finally open to the settlement of Germanic tribes.

In the Early Middle Ages, from the end of the 4th century, the western extent of modern-day Switzerland was part of the territory of the Kings of the Burgundians. The Alemanni settled the Swiss plateau in the 5th century and the valleys of the Alps in the 8th century, forming Alemannia. Modern-day Switzerland was therefore then divided between the kingdoms of Alemannia and Burgundy.[31] The entire region became part of the expanding Frankish Empire in the 6th century, following Clovis I's victory over the Alemanni at Tolbiac in 504 AD, and later Frankish domination of the Burgundians.[33][34]

Throughout the rest of the 6th, 7th and 8th centuries the Swiss regions continued under Frankish hegemony (Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties). But after its extension under Charlemagne, the Frankish Empire was divided by the Treaty of Verdun in 843.[31] The territories of present-day Switzerland became divided into Middle Francia and East Francia until they were reunified under the Holy Roman Empire around 1000 AD.[31]

By 1200, the Swiss plateau comprised the dominions of the houses of Savoy, Zähringer, Habsburg, and Kyburg.[31] Some regions (Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, later known as Waldstätten) were accorded the Imperial immediacy to grant the empire direct control over the mountain passes. With the extinction of its male line in 1263 the Kyburg dynasty fell in AD 1264; then the Habsburgs under King Rudolph I (Holy Roman Emperor in 1273) laid claim to the Kyburg lands and annexed them extending their territory to the eastern Swiss plateau.[33]

Archaeological findings

A female who died in about 200 BC was found buried in a carved tree trunk during a construction project at the Kern school complex in March 2017 in Aussersihl. Archaeologists revealed that she was approximately 40 years old when she died and likely carried out little physical labor when she was alive. A sheepskin coat, a belt chain, a fancy wool dress, a scarf and a pendant made of glass and amber beads were also discovered with the woman.[35][36][37][38][39]

Old Swiss Confederacy

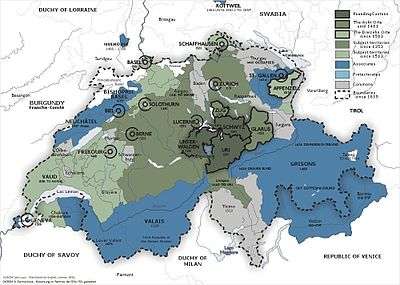

The Old Swiss Confederacy was an alliance among the valley communities of the central Alps. The Confederacy, governed by nobles and patricians of various cantons, facilitated management of common interests and ensured peace on the important mountain trade routes. The Federal Charter of 1291 agreed between the rural communes of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden is considered the confederacy's founding document, even though similar alliances are likely to have existed decades earlier.[40][41]

By 1353, the three original cantons had joined with the cantons of Glarus and Zug and the Lucerne, Zürich and Bern city states to form the "Old Confederacy" of eight states that existed until the end of the 15th century. The expansion led to increased power and wealth for the confederation.[41] By 1460, the confederates controlled most of the territory south and west of the Rhine to the Alps and the Jura mountains, particularly after victories against the Habsburgs (Battle of Sempach, Battle of Näfels), over Charles the Bold of Burgundy during the 1470s, and the success of the Swiss mercenaries. The Swiss victory in the Swabian War against the Swabian League of Emperor Maximilian I in 1499 amounted to de facto independence within the Holy Roman Empire.[41] In 1501, Basel and Schaffhausen joined the Old Swiss Confederacy.

The Old Swiss Confederacy had acquired a reputation of invincibility during these earlier wars, but expansion of the confederation suffered a setback in 1515 with the Swiss defeat in the Battle of Marignano. This ended the so-called "heroic" epoch of Swiss history.[41] The success of Zwingli's Reformation in some cantons led to inter-cantonal religious conflicts in 1529 and 1531 (Wars of Kappel). It was not until more than one hundred years after these internal wars that, in 1648, under the Peace of Westphalia, European countries recognised Switzerland's independence from the Holy Roman Empire and its neutrality.[33][34]

During the Early Modern period of Swiss history, the growing authoritarianism of the patriciate families combined with a financial crisis in the wake of the Thirty Years' War led to the Swiss peasant war of 1653. In the background to this struggle, the conflict between Catholic and Protestant cantons persisted, erupting in further violence at the First War of Villmergen, in 1656, and the Toggenburg War (or Second War of Villmergen), in 1712.[41]

Napoleonic era

In 1798, the revolutionary French government conquered Switzerland and imposed a new unified constitution.[41] This centralised the government of the country, effectively abolishing the cantons: moreover, Mülhausen joined France and the Valtellina valley became part of the Cisalpine Republic, separating from Switzerland. The new regime, known as the Helvetic Republic, was highly unpopular. It had been imposed by a foreign invading army and destroyed centuries of tradition, making Switzerland nothing more than a French satellite state. The fierce French suppression of the Nidwalden Revolt in September 1798 was an example of the oppressive presence of the French Army and the local population's resistance to the occupation.

When war broke out between France and its rivals, Russian and Austrian forces invaded Switzerland. The Swiss refused to fight alongside the French in the name of the Helvetic Republic. In 1803 Napoleon organised a meeting of the leading Swiss politicians from both sides in Paris. The result was the Act of Mediation which largely restored Swiss autonomy and introduced a Confederation of 19 cantons.[41] Henceforth, much of Swiss politics would concern balancing the cantons' tradition of self-rule with the need for a central government.

In 1815 the Congress of Vienna fully re-established Swiss independence and the European powers agreed to permanently recognise Swiss neutrality.[33][34][41] Swiss troops still served foreign governments until 1860 when they fought in the Siege of Gaeta. The treaty also allowed Switzerland to increase its territory, with the admission of the cantons of Valais, Neuchâtel and Geneva. Switzerland's borders have not changed since, except for some minor adjustments.[42]

Federal state

The restoration of power to the patriciate was only temporary. After a period of unrest with repeated violent clashes, such as the Züriputsch of 1839, civil war (the Sonderbundskrieg) broke out in 1847 when some Catholic cantons tried to set up a separate alliance (the Sonderbund).[41] The war lasted for less than a month, causing fewer than 100 casualties, most of which were through friendly fire. Yet however minor the Sonderbundskrieg appears compared with other European riots and wars in the 19th century, it nevertheless had a major impact on both the psychology and the society of the Swiss and of Switzerland.

The war convinced most Swiss of the need for unity and strength towards its European neighbours. Swiss people from all strata of society, whether Catholic or Protestant, from the liberal or conservative current, realised that the cantons would profit more if their economic and religious interests were merged.

Thus, while the rest of Europe saw revolutionary uprisings, the Swiss drew up a constitution which provided for a federal layout, much of it inspired by the American example. This constitution provided for a central authority while leaving the cantons the right to self-government on local issues. Giving credit to those who favoured the power of the cantons (the Sonderbund Kantone), the national assembly was divided between an upper house (the Council of States, two representatives per canton) and a lower house (the National Council, with representatives elected from across the country). Referendums were made mandatory for any amendment of this constitution.[34] This new constitution also brought a legal end to nobility in Switzerland.[43]

A system of single weights and measures was introduced and in 1850 the Swiss franc became the Swiss single currency. Article 11 of the constitution forbade sending troops to serve abroad, with the exception of serving the Holy See, though the Swiss were still obliged to serve Francis II of the Two Sicilies with Swiss Guards present at the Siege of Gaeta in 1860, marking the end of foreign service.

An important clause of the constitution was that it could be re-written completely if this was deemed necessary, thus enabling it to evolve as a whole rather than being modified one amendment at a time.[44]

This need soon proved itself when the rise in population and the Industrial Revolution that followed led to calls to modify the constitution accordingly. An early draft was rejected by the population in 1872 but modifications led to its acceptance in 1874.[41] It introduced the facultative referendum for laws at the federal level. It also established federal responsibility for defence, trade, and legal matters.

In 1891, the constitution was revised with unusually strong elements of direct democracy, which remain unique even today.[41]

Modern history

Switzerland was not invaded during either of the world wars. During World War I, Switzerland was home to Vladimir Illych Ulyanov (Vladimir Lenin) and he remained there until 1917.[45] Swiss neutrality was seriously questioned by the Grimm–Hoffmann Affair in 1917, but it was short-lived. In 1920, Switzerland joined the League of Nations, which was based in Geneva, on condition that it was exempt from any military requirements.

During World War II, detailed invasion plans were drawn up by the Germans,[46] but Switzerland was never attacked.[41] Switzerland was able to remain independent through a combination of military deterrence, concessions to Germany, and good fortune as larger events during the war delayed an invasion.[34][47] Under General Henri Guisan, appointed the commander-in-chief for the duration of the war, a general mobilisation of the armed forces was ordered. The Swiss military strategy was changed from one of static defence at the borders to protect the economic heartland, to one of organised long-term attrition and withdrawal to strong, well-stockpiled positions high in the Alps known as the Reduit. Switzerland was an important base for espionage by both sides in the conflict and often mediated communications between the Axis and Allied powers.[47]

Switzerland's trade was blockaded by both the Allies and by the Axis. Economic cooperation and extension of credit to the Third Reich varied according to the perceived likelihood of invasion and the availability of other trading partners. Concessions reached a peak after a crucial rail link through Vichy France was severed in 1942, leaving Switzerland (together with Liechtenstein) entirely isolated from the wider world by Axis controlled territory. Over the course of the war, Switzerland interned over 300,000 refugees[48] and the International Red Cross, based in Geneva, played an important part during the conflict. Strict immigration and asylum policies as well as the financial relationships with Nazi Germany raised controversy, but not until the end of the 20th century.[49]

During the war, the Swiss Air Force engaged aircraft of both sides, shooting down 11 intruding Luftwaffe planes in May and June 1940, then forcing down other intruders after a change of policy following threats from Germany. Over 100 Allied bombers and their crews were interned during the war. Between 1940 and 1945, Switzerland was bombed by the Allies causing fatalities and property damage.[47] Among the cities and towns bombed were Basel, Brusio, Chiasso, Cornol, Geneva, Koblenz, Niederweningen, Rafz, Renens, Samedan, Schaffhausen, Stein am Rhein, Tägerwilen, Thayngen, Vals, and Zürich. Allied forces explained the bombings, which violated the 96th Article of War, resulted from navigation errors, equipment failure, weather conditions, and errors made by bomber pilots. The Swiss expressed fear and concern that the bombings were intended to put pressure on Switzerland to end economic cooperation and neutrality with Nazi Germany.[50] Court-martial proceedings took place in England and the U.S. Government paid 62,176,433.06 in Swiss francs for reparations of the bombings.

Switzerland's attitude towards refugees was complicated and controversial; over the course of the war it admitted as many as 300,000 refugees[48] while refusing tens of thousands more,[51] including Jews who were severely persecuted by the Nazis.

After the war, the Swiss government exported credits through the charitable fund known as the Schweizerspende and also donated to the Marshall Plan to help Europe's recovery, efforts that ultimately benefited the Swiss economy.[52]

During the Cold War, Swiss authorities considered the construction of a Swiss nuclear bomb.[53] Leading nuclear physicists at the Federal Institute of Technology Zürich such as Paul Scherrer made this a realistic possibility. In 1988, the Paul Scherrer Institute was founded in his name to explore the therapeutic uses of neutron scattering technologies. Financial problems with the defence budget and ethical considerations prevented the substantial funds from being allocated, and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1968 was seen as a valid alternative. All remaining plans for building nuclear weapons were dropped by 1988.[54]

Switzerland was the last Western republic to grant women the right to vote. Some Swiss cantons approved this in 1959, while at the federal level it was achieved in 1971[41][55] and, after resistance, in the last canton Appenzell Innerrhoden (one of only two remaining Landsgemeinde, along with Glarus) in 1990. After obtaining suffrage at the federal level, women quickly rose in political significance, with the first woman on the seven member Federal Council executive being Elisabeth Kopp, who served from 1984 to 1989,[41] and the first female president being Ruth Dreifuss in 1999.

Switzerland joined the Council of Europe in 1963.[34] In 1979 areas from the canton of Bern attained independence from the Bernese, forming the new canton of Jura. On 18 April 1999 the Swiss population and the cantons voted in favour of a completely revised federal constitution.[41]

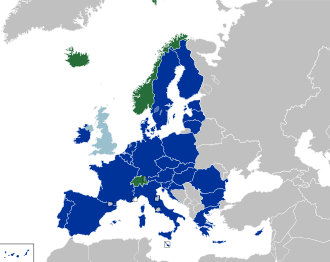

In 2002 Switzerland became a full member of the United Nations, leaving the Vatican City as the last widely recognised state without full UN membership. Switzerland is a founding member of the EFTA, but is not a member of the European Economic Area. An application for membership in the European Union was sent in May 1992, but not advanced since the EEA was rejected in December 1992[41] when Switzerland was the only country to launch a referendum on the EEA. There have since been several referendums on the EU issue; due to opposition from the citizens, the membership application has been withdrawn. Nonetheless, Swiss law is gradually being adjusted to conform with that of the EU, and the government has signed a number of bilateral agreements with the European Union. Switzerland, together with Liechtenstein, has been completely surrounded by the EU since Austria's entry in 1995. On 5 June 2005, Swiss voters agreed by a 55% majority to join the Schengen treaty, a result that was regarded by EU commentators as a sign of support by Switzerland, a country that is traditionally perceived as independent and reluctant to enter supranational bodies.[34]

Geography

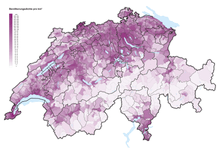

Extending across the north and south side of the Alps in west-central Europe, Switzerland encompasses a great diversity of landscapes and climates on a limited area of 41,285 square kilometres (15,940 sq mi).[56] The population is about 8 million, resulting in an average population density of around 195 people per square kilometre (500/sq mi).[56][57] The more mountainous southern half of the country is far more sparsely populated than the northern half.[56] In the largest Canton of Graubünden, lying entirely in the Alps, population density falls to 27 /km² (70 /sq mi).[58]

Switzerland lies between latitudes 45° and 48° N, and longitudes 5° and 11° E. It contains three basic topographical areas: the Swiss Alps to the south, the Swiss Plateau or Central Plateau, and the Jura mountains on the west. The Alps are a high mountain range running across the central-south of the country, constituting about 60% of the country's total area. The majority of the Swiss population live in the Swiss Plateau. Among the high valleys of the Swiss Alps many glaciers are found, totalling an area of 1,063 square kilometres (410 sq mi). From these originate the headwaters of several major rivers, such as the Rhine, Inn, Ticino and Rhône, which flow in the four cardinal directions into the whole of Europe. The hydrographic network includes several of the largest bodies of freshwater in Central and Western Europe, among which are included Lake Geneva (also called le Lac Léman in French), Lake Constance (known as Bodensee in German) and Lake Maggiore. Switzerland has more than 1500 lakes, and contains 6% of Europe's stock of fresh water. Lakes and glaciers cover about 6% of the national territory. The largest lake is Lake Geneva, in western Switzerland shared with France. The Rhône is both the main source and outflow of Lake Geneva. Lake Constance is the second largest Swiss lake and, like the Lake Geneva, an intermediate step by the Rhine at the border to Austria and Germany. While the Rhône flows into the Mediterranean Sea at the French Camargue region and the Rhine flows into the North Sea at Rotterdam in the Netherlands, about 1,000 kilometres (620 miles) apart, both springs are only about 22 kilometres (14 miles) apart from each other in the Swiss Alps.[56][59]

Forty-eight of Switzerland's mountains are 4,000 metres (13,000 ft) above sea in altitude or higher.[56] At 4,634 m (15,203 ft), Monte Rosa is the highest, although the Matterhorn (4,478 m or 14,692 ft) is often regarded as the most famous. Both are located within the Pennine Alps in the canton of Valais, on the border with Italy. The section of the Bernese Alps above the deep glacial Lauterbrunnen valley, containing 72 waterfalls, is well known for the Jungfrau (4,158 m or 13,642 ft) Eiger and Mönch, and the many picturesque valleys in the region. In the southeast the long Engadin Valley, encompassing the St. Moritz area in canton of Graubünden, is also well known; the highest peak in the neighbouring Bernina Alps is Piz Bernina (4,049 m or 13,284 ft).[56]

The more populous northern part of the country, constituting about 30% of the country's total area, is called the Swiss Plateau. It has greater open and hilly landscapes, partly forested, partly open pastures, usually with grazing herds, or vegetables and fruit fields, but it is still hilly. There are large lakes found here and the biggest Swiss cities are in this area of the country.[56]

Within Switzerland there are two small enclaves: Büsingen belongs to Germany, Campione d'Italia belongs to Italy.[60] Switzerland has no exclaves in other countries.

Climate

The Swiss climate is generally temperate, but can vary greatly between the localities,[61] from glacial conditions on the mountaintops to the often pleasant near Mediterranean climate at Switzerland's southern tip. There are some valley areas in the southern part of Switzerland where some cold-hardy palm trees are found. Summers tend to be warm and humid at times with periodic rainfall so they are ideal for pastures and grazing. The less humid winters in the mountains may see long intervals of stable conditions for weeks, while the lower lands tend to suffer from inversion, during these periods, thus seeing no sun for weeks.

A weather phenomenon known as the föhn (with an identical effect to the chinook wind) can occur at all times of the year and is characterised by an unexpectedly warm wind, bringing air of very low relative humidity to the north of the Alps during rainfall periods on the southern face of the Alps. This works both ways across the alps but is more efficient if blowing from the south due to the steeper step for oncoming wind from the south. Valleys running south to north trigger the best effect. The driest conditions persist in all inner alpine valleys that receive less rain because arriving clouds lose a lot of their content while crossing the mountains before reaching these areas. Large alpine areas such as Graubünden remain drier than pre-alpine areas and as in the main valley of the Valais wine grapes are grown there.[62]

The wettest conditions persist in the high Alps and in the Ticino canton which has much sun yet heavy bursts of rain from time to time.[62] Precipitation tends to be spread moderately throughout the year with a peak in summer. Autumn is the driest season, winter receives less precipitation than summer, yet the weather patterns in Switzerland are not in a stable climate system and can be variable from year to year with no strict and predictable periods.

Environment

Switzerland's ecosystems can be particularly fragile, because the many delicate valleys separated by high mountains often form unique ecologies. The mountainous regions themselves are also vulnerable, with a rich range of plants not found at other altitudes, and experience some pressure from visitors and grazing. The climatic, geological and topographical conditions of the alpine region make for a very fragile ecosystem that is particularly sensitive to climate change.[61][64] Nevertheless, according to the 2014 Environmental Performance Index, Switzerland ranks first among 132 nations in safeguarding the environment, due to its high scores on environmental public health, its heavy reliance on renewable sources of energy (hydropower and geothermal energy), and its control of greenhouse gas emissions.[65]

However, access to biocapacity in Switzerland is far lower than world average. In 2016, Switzerland had 1.0 global hectares[66] of biocapacity per person within its territory, 40 percent less than world average of 1.6 global hectares per person. In contrast, in 2016, they used 4.6 global hectares of biocapacity - their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they used about 4.6 times as much biocapacity as Switzerland contains. The remainder comes from imports and overusing the global commons (such as the atmosphere through greenhouse gas emissions). As a result, Switzerland is running a biocapacity deficit.[66]

Politics

The Federal Constitution adopted in 1848 is the legal foundation of the modern federal state.[67] A new Swiss Constitution was adopted in 1999, but did not introduce notable changes to the federal structure. It outlines basic and political rights of individuals and citizen participation in public affairs, divides the powers between the Confederation and the cantons and defines federal jurisdiction and authority. There are three main governing bodies on the federal level:[68] the bicameral parliament (legislative), the Federal Council (executive) and the Federal Court (judicial).

The Swiss Parliament consists of two houses: the Council of States which has 46 representatives (two from each canton and one from each half-canton) who are elected under a system determined by each canton, and the National Council, which consists of 200 members who are elected under a system of proportional representation, depending on the population of each canton. Members of both houses serve for 4 years and only serve as members of parliament part-time (so-called Milizsystem or citizen legislature).[69] When both houses are in joint session, they are known collectively as the Federal Assembly. Through referendums, citizens may challenge any law passed by parliament and through initiatives, introduce amendments to the federal constitution, thus making Switzerland a direct democracy.[67]

The Federal Council constitutes the federal government, directs the federal administration and serves as collective Head of State. It is a collegial body of seven members, elected for a four-year mandate by the Federal Assembly which also exercises oversight over the Council. The President of the Confederation is elected by the Assembly from among the seven members, traditionally in rotation and for a one-year term; the President chairs the government and assumes representative functions. However, the president is a primus inter pares with no additional powers, and remains the head of a department within the administration.[67]

The Swiss government has been a coalition of the four major political parties since 1959, each party having a number of seats that roughly reflects its share of electorate and representation in the federal parliament. The classic distribution of 2 CVP/PDC, 2 SPS/PSS, 2 FDP/PRD and 1 SVP/UDC as it stood from 1959 to 2003 was known as the "magic formula". Following the 2015 Federal Council elections, the seven seats in the Federal Council were distributed as follows:

- 1 seat for the Christian Democratic People's Party (CVP/PDC),

- 2 seats for the Free Democratic Party (FDP/PRD),

- 2 seats for the Social Democratic Party (SPS/PSS),

- 2 seats for the Swiss People's Party (SVP/UDC).

The function of the Federal Supreme Court is to hear appeals against rulings of cantonal or federal courts. The judges are elected by the Federal Assembly for six-year terms.[70]

Direct democracy

Direct democracy and federalism are hallmarks of the Swiss political system.[71] Swiss citizens are subject to three legal jurisdictions: the municipality, canton and federal levels. The 1848 and 1999 Swiss Constitutions define a system of direct democracy (sometimes called half-direct or representative direct democracy because it is aided by the more commonplace institutions of a representative democracy). The instruments of this system at the federal level, known as popular rights (German: Volksrechte, French: droits populaires, Italian: diritti popolari),[72] include the right to submit a federal initiative and a referendum, both of which may overturn parliamentary decisions.[67][73]

By calling a federal referendum, a group of citizens may challenge a law passed by parliament, if they gather 50,000 signatures against the law within 100 days. If so, a national vote is scheduled where voters decide by a simple majority whether to accept or reject the law. Any 8 cantons together can also call a constitutional referendum on a federal law.[67]

Similarly, the federal constitutional initiative allows citizens to put a constitutional amendment to a national vote, if 100,000 voters sign the proposed amendment within 18 months.[note 8] The Federal Council and the Federal Assembly can supplement the proposed amendment with a counter-proposal, and then voters must indicate a preference on the ballot in case both proposals are accepted. Constitutional amendments, whether introduced by initiative or in parliament, must be accepted by a double majority of the national popular vote and the cantonal popular votes.[note 9][71]

Cantons

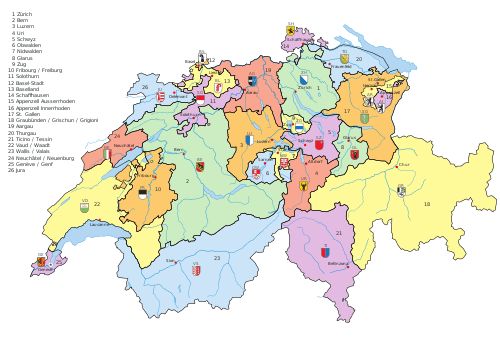

The Swiss Confederation consists of 26 cantons:[67][74]

|

| Canton | ID | Capital | Canton | ID | Capital | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aargau | 19 | Aarau | *Nidwalden | 7 | Stans | ||

| *Appenzell Ausserrhoden | 15 | Herisau | *Obwalden | 6 | Sarnen | ||

| *Appenzell Innerrhoden | 16 | Appenzell | Schaffhausen | 14 | Schaffhausen | ||

| *Basel-Landschaft | 13 | Liestal | Schwyz | 5 | Schwyz | ||

| *Basel-Stadt | 12 | Basel | Solothurn | 11 | Solothurn | ||

| Bern | 2 | Bern | St. Gallen | 17 | St. Gallen | ||

| Fribourg | 10 | Fribourg | Thurgau | 20 | Frauenfeld | ||

| Geneva | 25 | Geneva | Ticino | 21 | Bellinzona | ||

| Glarus | 8 | Glarus | Uri | 4 | Altdorf | ||

| Grisons | 18 | Chur | Valais | 23 | Sion | ||

| Jura | 26 | Delémont | Vaud | 22 | Lausanne | ||

| Lucerne | 3 | Lucerne | Zug | 9 | Zug | ||

| Neuchâtel | 24 | Neuchâtel | Zürich | 1 | Zürich | ||

*These cantons are known as half-cantons.

The cantons are federated states, have a permanent constitutional status and, in comparison with the situation in other countries, a high degree of independence. Under the Federal Constitution, all 26 cantons are equal in status, except that 6 (referred to often as the half-cantons) are represented by only one councillor (instead of two) in the Council of States and have only half a cantonal vote with respect to the required cantonal majority in referendums on constitutional amendments. Each canton has its own constitution, and its own parliament, government, police and courts.[74] However, there are considerable differences between the individual cantons, most particularly in terms of population and geographical area. Their populations vary between 16,003 (Appenzell Innerrhoden) and 1,487,969 (Zürich), and their area between 37 km2 (14 sq mi) (Basel-Stadt) and 7,105 km2 (2,743 sq mi) (Grisons).

Municipalities

The cantons comprise a total of 2,222 municipalities as of 2018.

Foreign relations and international institutions

Traditionally, Switzerland avoids alliances that might entail military, political, or direct economic action and has been neutral since the end of its expansion in 1515. Its policy of neutrality was internationally recognised at the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[75][76] Only in 2002 did Switzerland become a full member of the United Nations[75] and it was the first state to join it by referendum. Switzerland maintains diplomatic relations with almost all countries and historically has served as an intermediary between other states.[75] Switzerland is not a member of the European Union; the Swiss people have consistently rejected membership since the early 1990s.[75] However, Switzerland does participate in the Schengen Area.[77] Swiss neutrality has been questioned at times.[78][79][80][81][82]

Many international institutions have their seats in Switzerland, in part because of its policy of neutrality. Geneva is the birthplace of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, the Geneva Conventions and, since 2006, hosts the United Nations Human Rights Council. Even though Switzerland is one of the most recent countries to have joined the United Nations, the Palace of Nations in Geneva is the second biggest centre for the United Nations after New York, and Switzerland was a founding member and home to the League of Nations.

Apart from the United Nations headquarters, the Swiss Confederation is host to many UN agencies, like the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Labour Organization (ILO), the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and about 200 other international organisations, including the World Trade Organization and the World Intellectual Property Organization.[75] The annual meetings of the World Economic Forum in Davos bring together top international business and political leaders from Switzerland and foreign countries to discuss important issues facing the world, including health and the environment. Additionally the headquarters of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) are located in Basel since 1930.

Furthermore, many sport federations and organisations are located throughout the country, such as the International Handball Federation in Basel, the International Basketball Federation in Geneva, the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) in Nyon, the International Federation of Association Football (FIFA) and the International Ice Hockey Federation both in Zürich, the International Cycling Union in Aigle, and the International Olympic Committee in Lausanne.[84]

Military

The Swiss Armed Forces, including the Land Forces and the Air Force, are composed mostly of conscripts, male citizens aged from 20 to 34 (in special cases up to 50) years. Being a landlocked country, Switzerland has no navy; however, on lakes bordering neighbouring countries, armed military patrol boats are used. Swiss citizens are prohibited from serving in foreign armies, except for the Swiss Guards of the Vatican, or if they are dual citizens of a foreign country and reside there.

The structure of the Swiss militia system stipulates that the soldiers keep their Army issued equipment, including all personal weapons, at home. Some organisations and political parties find this practice controversial.[85] Women can serve voluntarily. Men usually receive military conscription orders for training at the age of 18.[86] About two thirds of the young Swiss are found suited for service; for those found unsuited, various forms of alternative service exist.[87] Annually, approximately 20,000 persons are trained in recruit centres for a duration from 18 to 21 weeks. The reform "Army XXI" was adopted by popular vote in 2003, it replaced the previous model "Army 95", reducing the effectives from 400,000 to about 200,000. Of those, 120,000 are active in periodic Army training and 80,000 are non-training reserves.[88]

Overall, three general mobilisations have been declared to ensure the integrity and neutrality of Switzerland. The first one was held on the occasion of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71. The second was in response to the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914. The third mobilisation of the army took place in September 1939 in response to the German attack on Poland; Henri Guisan was elected as the General-in-Chief.

Because of its neutrality policy, the Swiss army does not currently take part in armed conflicts in other countries, but is part of some peacekeeping missions around the world. Since 2000 the armed force department has also maintained the Onyx intelligence gathering system to monitor satellite communications.[89] Switzerland decided not to sign the Nuclear Weapon Ban Treaty.[90]

Following the end of the Cold War there have been a number of attempts to curb military activity or even abolish the armed forces altogether. A notable referendum on the subject, launched by an anti-militarist group, was held on 26 November 1989. It was defeated with about two thirds of the voters against the proposal.[91][92] A similar referendum, called for before, but held shortly after the 11 September attacks in the US, was defeated by over 78% of voters.[93]

Gun politics in Switzerland are unique in Europe in that 29% of citizens are legally armed. The large majority of firearms kept at home are issued by the Swiss army, but ammunition is no longer issued.[94][95]

The capital or Federal City issue

Until 1848 the rather loosely coupled Confederation did not know a central political organisation, but representatives, mayors, and Landammänner met several times a year at the capital of the Lieu presiding the Confederal Diet for one year.

.jpg)

Until 1500 the legates met most of the time in Lucerne, but also in Zürich, Baden, Bern, Schwyz etc., but sometimes also at places outside of the confederation, such as Constance. From the Swabian War in 1499 onwards until Reformation, most conferences met in Zurich. Afterwards the town hall at Baden, where the annual accounts of the common people had been held regularly since 1426, became the most frequent, but not the sole place of assembly. After 1712 Frauenfeld gradually dissolved Baden. From 1526, the Catholic conferences were held mostly in Lucerne, the Protestant conferences from 1528 mostly in Aarau, the one for the legitimation of the French Ambassador in Solothurn. At the same time the syndicate for the Ennetbirgischen Vogteien located in the present Ticino met from 1513 in Lugano and Locarno.[96]

After the Helvetic Republic and during the Mediation from 1803 until 1815 the Confederal Diet of the 19 Lieus met at the capitals of the directoral cantons Fribourg, Berne, Basel, Zurich, Lucerne and Solothurn.[96]

After the Long Diet from 6 April 1814 to 31 August 1815 took place in Zurich to replace the constitution and the enhancement of the Confederation to 22 cantons by the admission of the cantons of Valais, Neuchâtel and Geneva to full members, the directoral cantons of Lucerne, Zurich and Berne took over the diet in two-year turns.[96]

In 1848, the federal constitution provided that details concerning the federal institutions, such as their locations, should be taken care of by the Federal Assembly (BV 1848 Art. 108). Thus on 28 November 1848, the Federal Assembly voted in majority to locate the seat of government in Berne. And, as a prototypical federal compromise, to assign other federal institutions, such as the Federal Polytechnical School (1854, the later ETH) to Zurich, and other institutions to Lucerne, such as the later SUVA (1912) and the Federal Insurance Court (1917). In 1875, a law (RS 112) fixed the compensations owed by the city of Bern for the federal seat.[1] According to these living fundamental federalistic feelings further federal institutions were subsequently attributed to Lausanne (Federal Supreme Court in 1872, and EPFL in 1969), Bellinzona (Federal Criminal Court, 2004), and St. Gallen (Federal Administrative Court and Federal Patent Court, 2012).

The 1999 new constitution, however, does not contain anything concerning any Federal City. In 2002 a tripartite committee has been asked by the Swiss Federal Council to prepare the "creation of a federal law on the status of Bern as a Federal City", and to evaluate the positive and negative aspects for the city and the canton of Bern if this status were awarded. After a first report the work of this committee was suspended in 2004 by the Swiss Federal Council, and work on this subject has not resumed since.[97]

Thus as of today, no city in Switzerland has the official status either of capital or of Federal City, nevertheless Berne is commonly referred to as "Federal City" (German: Bundesstadt, French: ville fédérale, Italian: città federale).

Economy and labour law

Switzerland has a stable, prosperous and high-tech economy and enjoys great wealth, being ranked as the wealthiest country in the world per capita in multiple rankings, while at the same time being one the least corrupt countries in the world.[100][101][102] It has the world's twentieth largest economy by nominal GDP and the thirty-eighth largest by purchasing power parity. It is the seventeenth largest exporter. Zürich and Geneva are regarded as global cities, ranked as Alpha and Beta respectively. Basel is the capital of the pharmaceutical industry in Switzerland. With its world-class companies, Novartis and Roche, and many other players, it is also one of the world's most important centres for the life sciences industry.[103]

Switzerland has the highest European rating in the Index of Economic Freedom 2010, while also providing large coverage through public services.[104] The nominal per capita GDP is higher than those of the larger Western and Central European economies and Japan.[105] In terms of GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power, Switzerland was ranked 5th in the world in 2018 by World Bank[106] and estimated at 9th by the IMF in 2020[107], as well as 11th by the CIA World Factbook in 2017[108].

The World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness Report currently ranks Switzerland's economy as the most competitive in the world,[110] while ranked by the European Union as Europe's most innovative country.[111][112] It is a relatively easy place to do business, currently ranking 20th of 189 countries in the Ease of Doing Business Index. The slow growth Switzerland experienced in the 1990s and the early 2000s has brought greater support for economic reforms and harmonisation with the European Union.[113][114]

For much of the 20th century, Switzerland was the wealthiest country in Europe by a considerable margin (by GDP – per capita).[115] Switzerland also has one of the world's largest account balances as a percentage of GDP.[116] In 2018, the canton of Basel-City had the highest GDP per capita in the country, ahead of the cantons of Zug and Geneva.[117] According to Credit Suisse, only about 37% of residents own their own homes, one of the lowest rates of home ownership in Europe. Housing and food price levels were 171% and 145% of the EU-25 index in 2007, compared to 113% and 104% in Germany.[118]

Origin of the capital at the 30 biggest Swiss corporations, 2018[119]

Switzerland is home to several large multinational corporations. The largest Swiss companies by revenue are Glencore, Gunvor, Nestlé, Novartis, Hoffmann-La Roche, ABB, Mercuria Energy Group and Adecco.[120] Also, notable are UBS AG, Zurich Financial Services, Credit Suisse, Barry Callebaut, Swiss Re, Tetra Pak, The Swatch Group and Swiss International Air Lines. Switzerland is ranked as having one of the most powerful economies in the world.[115]

Switzerland's most important economic sector is manufacturing. Manufacturing consists largely of the production of specialist chemicals, health and pharmaceutical goods, scientific and precision measuring instruments and musical instruments. The largest exported goods are chemicals (34% of exported goods), machines/electronics (20.9%), and precision instruments/watches (16.9%).[118] Exported services amount to a third of exports.[118] The service sector – especially banking and insurance, tourism, and international organisations – is another important industry for Switzerland.

Agricultural protectionism—a rare exception to Switzerland's free trade policies—has contributed to high food prices. Product market liberalisation is lagging behind many EU countries according to the OECD.[113] Nevertheless, domestic purchasing power is one of the best in the world.[121][122][123] Apart from agriculture, economic and trade barriers between the European Union and Switzerland are minimal and Switzerland has free trade agreements worldwide. Switzerland is a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).

Taxation and government spending

Switzerland has an overwhelmingly private sector economy and low tax rates by Western World standards; overall taxation is one of the smallest of developed countries. The Swiss Federal budget had a size of 62.8 billion Swiss francs in 2010, which is an equivalent 11.35% of the country's GDP in that year; however, the regional (canton) budgets and the budgets of the municipalities are not counted as part of the federal budget and the total rate of government spending is closer to 33.8% of GDP. The main sources of income for the federal government are the value-added tax (33%) and the direct federal tax (29%) and the main expenditure is located in the areas of social welfare and finance & tax. The expenditures of the Swiss Confederation have been growing from 7% of GDP in 1960 to 9.7% in 1990 and to 10.7% in 2010. While the sectors social welfare and finance & tax have been growing from 35% in 1990 to 48.2% in 2010, a significant reduction of expenditures has been occurring in the sectors of agriculture and national defence; from 26.5% in to 12.4% (estimation for the year 2015).[124][125]

Labour market

Slightly more than 5 million people work in Switzerland;[126] about 25% of employees belonged to a trade union in 2004.[127] Switzerland has a more flexible job market than neighbouring countries and the unemployment rate is very low. The unemployment rate increased from a low of 1.7% in June 2000 to a peak of 4.4% in December 2009.[128] The unemployment rate decreased to 3.2% in 2014 and held steady at that level for several years,[129] before further dropping to 2.5% in 2018 and 2.3% in 2019.[130] Population growth from net immigration is quite high, at 0.52% of population in 2004, increased in the following years before falling to 0.54% again in 2017.[118][131] The foreign citizen population was 28.9% in 2015, about the same as in Australia. GDP per hour worked is the world's 16th highest, at 49.46 international dollars in 2012.[132]

In 2016, median monthly gross salary in Switzerland was 6,502 francs per month (equivalent to US$6,597 per month), is just enough to cover the high cost of living. After rent, taxes and social security contributions, plus spending on goods and services, the average household has about 15% of its gross income left for savings. Though 61% of the population made less than the average income, income inequality is relatively low with a Gini coefficient of 29.7, placing Switzerland among the top 20 countries for income equality.

About 8.2% of the population live below the national poverty line, defined in Switzerland as earning less than CHF3,990 per month for a household of two adults and two children, and a further 15% are at risk of poverty. Single-parent families, those with no post-compulsory education and those who are out of work are among the most likely to be living below the poverty line. Although getting a job is considered a way out of poverty, among the gainfully employed, some 4.3% are considered working poor. One in ten jobs in Switzerland is considered low-paid and roughly 12% of Swiss workers hold such jobs, many of them women and foreigners.

Education and science

Leonhard Euler (mathematics)

Louis Agassiz (glaciology)

Auguste Piccard (aeronautics)

Albert Einstein (physics)

Education in Switzerland is very diverse because the constitution of Switzerland delegates the authority for the school system to the cantons.[133] There are both public and private schools, including many private international schools. The minimum age for primary school is about six years in all cantons, but most cantons provide a free "children's school" starting at four or five years old.[133] Primary school continues until grade four, five or six, depending on the school. Traditionally, the first foreign language in school was always one of the other national languages, although recently (2000) English was introduced first in a few cantons.[133]

At the end of primary school (or at the beginning of secondary school), pupils are separated according to their capacities in several (often three) sections. The fastest learners are taught advanced classes to be prepared for further studies and the matura,[133] while students who assimilate a little more slowly receive an education more adapted to their needs.

There are 12 universities in Switzerland, ten of which are maintained at cantonal level and usually offer a range of non-technical subjects. The first university in Switzerland was founded in 1460 in Basel (with a faculty of medicine) and has a tradition of chemical and medical research in Switzerland. It is listed 87th on the 2019 Academic Ranking of World Universities.[134] The largest university in Switzerland is the University of Zurich with nearly 25,000 students.The Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ) and the University of Zurich are listed 20th and 54th respectively, on the 2015 Academic Ranking of World Universities.[135][136][137]

The two institutes sponsored by the federal government are the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ) in Zürich, founded 1855 and the EPFL in Lausanne, founded 1969 as such, which was formerly an institute associated with the University of Lausanne.[note 10][138][139]

In addition, there are various Universities of Applied Sciences. In business and management studies, the University of St. Gallen, (HSG) is ranked 329th in the world according to QS World University Rankings[140] and the International Institute for Management Development (IMD), was ranked first in open programmes worldwide by the Financial Times.[141] Switzerland has the second highest rate (almost 18% in 2003) of foreign students in tertiary education, after Australia (slightly over 18%).[142][143]

As might befit a country that plays home to innumerable international organisations, the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, located in Geneva, is not only continental Europe's oldest graduate school of international and development studies, but also widely believed to be one of its most prestigious.[144][145]

Many Nobel Prize laureates have been Swiss scientists. They include the world-famous physicist Albert Einstein[146] in the field of physics, who developed his special relativity while working in Bern. More recently Vladimir Prelog, Heinrich Rohrer, Richard Ernst, Edmond Fischer, Rolf Zinkernagel, Kurt Wüthrich and Jacques Dubochet received Nobel Prizes in the sciences. In total, 114 Nobel Prize winners in all fields stand in relation to Switzerland[147][note 11] and the Nobel Peace Prize has been awarded nine times to organisations residing in Switzerland.[148]

Geneva and the nearby French department of Ain co-host the world's largest laboratory, CERN,[150] dedicated to particle physics research. Another important research centre is the Paul Scherrer Institute. Notable inventions include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), diazepam (Valium), the scanning tunnelling microscope (Nobel prize) and Velcro. Some technologies enabled the exploration of new worlds such as the pressurised balloon of Auguste Piccard and the Bathyscaphe which permitted Jacques Piccard to reach the deepest point of the world's oceans.

Switzerland Space Agency, the Swiss Space Office, has been involved in various space technologies and programmes. In addition it was one of the 10 founders of the European Space Agency in 1975 and is the seventh largest contributor to the ESA budget. In the private sector, several companies are implicated in the space industry such as Oerlikon Space[151] or Maxon Motors[152] who provide spacecraft structures.

Switzerland and the European Union

Switzerland voted against membership in the European Economic Area in a referendum in December 1992 and has since maintained and developed its relationships with the European Union (EU) and European countries through bilateral agreements. In March 2001, the Swiss people refused in a popular vote to start accession negotiations with the EU.[153] In recent years, the Swiss have brought their economic practices largely into conformity with those of the EU in many ways, in an effort to enhance their international competitiveness. The economy grew at 3% in 2010, 1.9% in 2011, and 1% in 2012.[154] EU membership was a long-term objective of the Swiss government, but there was and remains considerable popular sentiment against membership, which is opposed by the conservative SVP party, the largest party in the National Council, and not currently supported or proposed by several other political parties. The application for membership of the EU was formally withdrawn in 2016, having long been frozen. The western French-speaking areas and the urban regions of the rest of the country tend to be more pro-EU, nonetheless with far from a significant share of the population.[155][156]

The government has established an Integration Office under the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Department of Economic Affairs. To minimise the negative consequences of Switzerland's isolation from the rest of Europe, Bern and Brussels signed seven bilateral agreements to further liberalise trade ties. These agreements were signed in 1999 and took effect in 2001. This first series of bilateral agreements included the free movement of persons. A second series covering nine areas was signed in 2004 and has since been ratified, which includes the Schengen Treaty and the Dublin Convention besides others.[157] They continue to discuss further areas for cooperation.[158]

In 2006, Switzerland approved 1 billion francs of supportive investment in the poorer Southern and Central European countries in support of cooperation and positive ties to the EU as a whole. A further referendum will be needed to approve 300 million francs to support Romania and Bulgaria and their recent admission. The Swiss have also been under EU and sometimes international pressure to reduce banking secrecy and to raise tax rates to parity with the EU. Preparatory discussions are being opened in four new areas: opening up the electricity market, participation in the European GNSS project Galileo, cooperating with the European centre for disease prevention and recognising certificates of origin for food products.[159]

On 27 November 2008, the interior and justice ministers of European Union in Brussels announced Switzerland's accession to the Schengen passport-free zone from 12 December 2008. The land border checkpoints will remain in place only for goods movements, but should not run controls on people, though people entering the country had their passports checked until 29 March 2009 if they originated from a Schengen nation.[160]

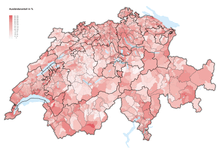

On 9 February 2014, Swiss voters narrowly approved by 50.3% a ballot initiative launched by the national conservative Swiss People's Party (SVP/UDC) to restrict immigration, and thus reintroducing a quota system on the influx of foreigners. This initiative was mostly backed by rural (57.6% approvals) and suburban agglomerations (51.2% approvals), and isolated towns (51.3% approvals) of Switzerland as well as by a strong majority (69.2% approval) in the canton of Ticino, while metropolitan centres (58.5% rejection) and the French-speaking part (58.5% rejection) of Switzerland rather rejected it.[161] Some news commentators claim that this proposal de facto contradicts the bilateral agreements on the free movement of persons from these respective countries.[162][163]

In December 2016, a compromise with the European Union was attained effectively canceling quotas on EU citizens but still allowing for favourable treatment of Swiss-based job applicants.[164]

Energy, infrastructure and environment

Electricity generated in Switzerland is 56% from hydroelectricity and 39% from nuclear power, resulting in a nearly CO2-free electricity-generating network. On 18 May 2003, two anti-nuclear initiatives were turned down: Moratorium Plus, aimed at forbidding the building of new nuclear power plants (41.6% supported and 58.4% opposed),[165] and Electricity Without Nuclear (33.7% supported and 66.3% opposed) after a previous moratorium expired in 2000.[166] However, as a reaction to the Fukushima nuclear disaster, the Swiss government announced in 2011 that it plans to end its use of nuclear energy in the next 2 or 3 decades.[167] In November 2016, Swiss voters rejected a proposal by the Green Party to accelerate the phaseout of nuclear power (45.8% supported and 54.2% opposed).[168] The Swiss Federal Office of Energy (SFOE) is the office responsible for all questions relating to energy supply and energy use within the Federal Department of Environment, Transport, Energy and Communications (DETEC). The agency is supporting the 2000-watt society initiative to cut the nation's energy use by more than half by the year 2050.[169]

The most dense rail network in Europe[55] of 5,250 kilometres (3,260 mi) carries over 596 million passengers annually (as of 2015).[170] In 2015, each Swiss resident travelled on average 2,550 kilometres (1,580 mi) by rail, which makes them the keenest rail users.[170] Virtually 100% of the network is electrified. The vast majority (60%) of the network is operated by the Swiss Federal Railways (SBB CFF FFS). Besides the second largest standard gauge railway company BLS AG two railways companies operating on narrow gauge networks are the Rhaetian Railway (RhB) in the southeastern canton of Graubünden, which includes some World Heritage lines,[171] and the Matterhorn Gotthard Bahn (MGB), which co-operates together with RhB the Glacier Express between Zermatt and St. Moritz/Davos. On 31 May 2016 the world's longest and deepest railway tunnel and the first flat, low-level route through the Alps, the 57.1-kilometre long (35.5 mi) Gotthard Base Tunnel, opened as the largest part of the New Railway Link through the Alps (NRLA) project after 17 years of realization. It started its daily business for passenger transport on 11 December 2016 replacing the old, mountainous, scenic route over and through the St Gotthard Massif.

Switzerland has a publicly managed road network without road tolls that is financed by highway permits as well as vehicle and gasoline taxes. The Swiss autobahn/autoroute system requires the purchase of a vignette (toll sticker)—which costs 40 Swiss francs—for one calendar year in order to use its roadways, for both passenger cars and trucks. The Swiss autobahn/autoroute network has a total length of 1,638 km (1,018 mi) (as of 2000) and has, by an area of 41,290 km2 (15,940 sq mi), also one of the highest motorway densities in the world.[172] Zurich Airport is Switzerland's largest international flight gateway, which handled 22.8 million passengers in 2012.[173] The other international airports are Geneva Airport (13.9 million passengers in 2012),[174] EuroAirport Basel Mulhouse Freiburg which is located in France, Bern Airport, Lugano Airport, St. Gallen-Altenrhein Airport and Sion Airport. Swiss International Air Lines is the flag carrier of Switzerland. Its main hub is Zürich, but it is legally domiciled in Basel.

Switzerland has one of the best environmental records among nations in the developed world;[175] it was one of the countries to sign the Kyoto Protocol in 1998 and ratified it in 2003. With Mexico and the Republic of Korea it forms the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG).[176] The country is heavily active in recycling and anti-littering regulations and is one of the top recyclers in the world, with 66% to 96% of recyclable materials being recycled, depending on the area of the country.[177] The 2014 Global Green Economy Index ranked Switzerland among the top 10 green economies in the world.[178]

Switzerland developed an efficient system to recycle most recyclable materials.[179] Publicly organised collection by volunteers and economical railway transport logistics started as early as 1865 under the leadership of the notable industrialist Hans Caspar Escher (Escher Wyss AG) when the first modern Swiss paper manufacturing plant was built in Biberist.[180]

Switzerland also has an economic system for garbage disposal, which is based mostly on recycling and energy-producing incinerators due to a strong political will to protect the environment.[181] As in other European countries, the illegal disposal of garbage is not tolerated at all and heavily fined. In almost all Swiss municipalities, stickers or dedicated garbage bags need to be purchased that allow for identification of disposable garbage.[182]

Demographics

In 2018, Switzerland's population slightly exceeded 8.5 million. In common with other developed countries, the Swiss population increased rapidly during the industrial era, quadrupling between 1800 and 1990 and has continued to grow. Like most of Europe, Switzerland faces an ageing population, albeit with consistent annual growth projected into 2035, due mostly to immigration and a fertility rate close to replacement level.[183] Switzerland subsequently has one of the oldest populations in the world, with the average age of 42.5 years.[184]

As of 2019, resident foreigners make up 25.2% of the population, one of the largest proportions in the developed world.[7] Most of these (64%) were from European Union or EFTA countries.[185] Italians were the largest single group of foreigners, with 15.6% of total foreign population, followed closely by Germans (15.2%), immigrants from Portugal (12.7%), France (5.6%), Serbia (5.3%), Turkey (3.8%), Spain (3.7%), and Austria (2%). Immigrants from Sri Lanka, most of them former Tamil refugees, were the largest group among people of Asian origin (6.3%).[185]

Additionally, the figures from 2012 show that 34.7% of the permanent resident population aged 15 or over in Switzerland (around 2.33 million), had an immigrant background. A third of this population (853,000) held Swiss citizenship. Four fifths of persons with an immigration background were themselves immigrants (first generation foreigners and native-born and naturalised Swiss citizens), whereas one fifth were born in Switzerland (second generation foreigners and native-born and naturalised Swiss citizens).[186]

In the 2000s, domestic and international institutions expressed concern about what was perceived as an increase in xenophobia, particularly in some political campaigns. In reply to one critical report, the Federal Council noted that "racism unfortunately is present in Switzerland", but stated that the high proportion of foreign citizens in the country, as well as the generally unproblematic integration of foreigners, underlined Switzerland's openness.[187] Follow-up study conducted in 2018 found that 59% considered racism a serious problem in Switzerland. [188] The proportion of the population that has reported being targeted by racial discrimination has increased in recent years, from 10% in 2014 to almost 17% in 2018, according to the Federal Statistical Office. [189]

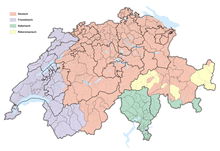

Languages

Switzerland has four national languages: mainly German (spoken by 62.8% of the population in 2016); French (22.9%) in the west; and Italian (8.2%) in the south.[191][190] The fourth national language, Romansh (0.5%), is a Romance language spoken locally in the southeastern trilingual canton of Grisons, and is designated by Article 4 of the Federal Constitution as a national language along with German, French, and Italian, and in Article 70 as an official language if the authorities communicate with persons who speak Romansh. However, federal laws and other official acts do not need to be decreed in Romansh.

In 2016, the languages most spoken at home among permanent residents aged 15 and older were Swiss German (59.4%), French (23.5%), Standard German (10.6%), and Italian (8.5%). Other languages spoken at home included English (5.0%), Portuguese (3.8%), Albanian (3.0%), Spanish (2.6%) and Serbian and Croatian (2.5%). 6.9% reported speaking another language at home.[192] In 2014 almost two-thirds (64.4%) of the permanent resident population indicated speaking more than one language regularly.[193]

The federal government is obliged to communicate in the official languages, and in the federal parliament simultaneous translation is provided from and into German, French and Italian.[194]

Aside from the official forms of their respective languages, the four linguistic regions of Switzerland also have their local dialectal forms. The role played by dialects in each linguistic region varies dramatically: in the German-speaking regions, Swiss German dialects have become ever more prevalent since the second half of the 20th century, especially in the media, such as radio and television, and are used as an everyday language for many, while the Swiss variety of Standard German is almost always used instead of dialect for written communication (c.f. diglossic usage of a language).[195] Conversely, in the French-speaking regions the local dialects have almost disappeared (only 6.3% of the population of Valais, 3.9% of Fribourg, and 3.1% of Jura still spoke dialects at the end of the 20th century), while in the Italian-speaking regions dialects are mostly limited to family settings and casual conversation.[195]

The principal official languages (German, French, and Italian) have terms, not used outside of Switzerland, known as Helvetisms. German Helvetisms are, roughly speaking, a large group of words typical of Swiss Standard German, which do not appear either in Standard German, nor in other German dialects. These include terms from Switzerland's surrounding language cultures (German Billett[196] from French), from similar terms in another language (Italian azione used not only as act but also as discount from German Aktion).[197] The French spoken in Switzerland has similar terms, which are equally known as Helvetisms. The most frequent characteristics of Helvetisms are in vocabulary, phrases, and pronunciation, but certain Helvetisms denote themselves as special in syntax and orthography likewise. Duden, the comprehensive German dictionary, contains about 3000 Helvetisms.[197] Current French dictionaries, such as the Petit Larousse, include several hundred Helvetisms.[198]

Learning one of the other national languages at school is compulsory for all Swiss pupils, so many Swiss are supposed to be at least bilingual, especially those belonging to linguistic minority groups.[199]

Health

Swiss residents are universally required to buy health insurance from private insurance companies, which in turn are required to accept every applicant. While the cost of the system is among the highest, it compares well with other European countries in terms of health outcomes; patients have been reported as being, in general, highly satisfied with it.[200][201][202] In 2012, life expectancy at birth was 80.4 years for men and 84.7 years for women[203] — the highest in the world.[204][205] However, spending on health is particularly high at 11.4% of GDP (2010), on par with Germany and France (11.6%) and other European countries, but notably less than spending in the USA (17.6%).[206] From 1990, a steady increase can be observed, reflecting the high costs of the services provided.[207] With an ageing population and new healthcare technologies, health spending will likely continue to rise.[207] Drug use is comparable to other developed countries with 14% of men and 6.5% of women between 20-24 saying they had consumed cannabis in the past 30 days[208] and 5 Swiss cities were listed among the top 10 European cities for cocaine use as measured in wastewater.[209][210]

Urbanisation

Between two thirds and three quarters of the population live in urban areas.[211][212] Switzerland has gone from a largely rural country to an urban one in just 70 years. Since 1935 urban development has claimed as much of the Swiss landscape as it did during the previous 2,000 years. This urban sprawl does not only affect the plateau but also the Jura and the Alpine foothills[213] and there are growing concerns about land use.[214] However, from the beginning of the 21st century, the population growth in urban areas is higher than in the countryside.[212]

Switzerland has a dense network of towns, where large, medium and small towns are complementary.[212] The plateau is very densely populated with about 450 people per km2 and the landscape continually shows signs of human presence.[215] The weight of the largest metropolitan areas, which are Zürich, Geneva–Lausanne, Basel and Bern tend to increase.[212] In international comparison the importance of these urban areas is stronger than their number of inhabitants suggests.[212] In addition the three main centres of Zürich, Geneva and Basel are recognised for their particularly great quality of life.[216]

Largest towns

Religion

| Affiliation | % of Swiss population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christian faiths | 66.5 | |

| Roman Catholic | 35.8 | |

| Swiss Reformed | 23.8 | |

| Eastern Orthodox | 2.5 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 1.2 | |

| Lutheran | 1.0 | |

| other Christian | 2.2 | |

| Non-Christian faiths | 6.6 | |

| Muslim | 5.3 | |

| Buddhist | 0.5 | |

| Hindu | 0.6 | |

| Jewish | 0.2 | |

| Other religious communities | 0.3 | |

| no religious affiliation | 26.3 | |

| unknown | 1.4 | |

Switzerland has no official state religion, though most of the cantons (except Geneva and Neuchâtel) recognise official churches, which are either the Roman Catholic Church or the Swiss Reformed Church. These churches, and in some cantons also the Old Catholic Church and Jewish congregations, are financed by official taxation of adherents.[218]

Christianity is the predominant religion of Switzerland (about 67% of resident population in 2016-2018[3] and 75% of Swiss citizens[219]), divided between the Roman Catholic Church (35.8% of the population), the Swiss Reformed Church (23.8%), further Protestant churches (2.2%), Eastern Orthodoxy (2.5%), and other Christian denominations (2.2%).[3] Immigration has established Islam (5.3%) as a sizeable minority religion.[3]

26.3% of Swiss permanent residents are not affiliated with any religious community (Atheism, Agnosticism, and others).[3]

As of the 2000 census other Christian minority communities included Neo-Pietism (0.44%), Pentecostalism (0.28%, mostly incorporated in the Schweizer Pfingstmission), Methodism (0.13%), the New Apostolic Church (0.45%), Jehovah's Witnesses (0.28%), other Protestant denominations (0.20%), the Old Catholic Church (0.18%), other Christian denominations (0.20%). Non-Christian religions are Hinduism (0.38%), Buddhism (0.29%), Judaism (0.25%) and others (0.11%); 4.3% did not make a statement.[220]