Gaul

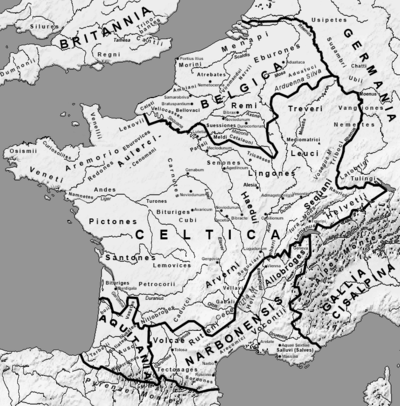

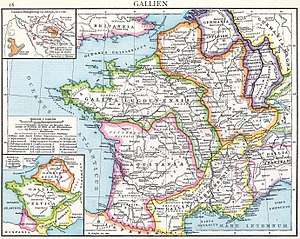

Gaul (Latin: Gallia)[1] was a region of Western Europe first described by the Romans.[2] It was inhabited by Celtic tribes, encompassing present day France, Luxembourg, Belgium, most of Switzerland, and parts of Northern Italy, Netherlands, and Germany, particularly the west bank of the Rhine. It covered an area of 494,000 km2 (191,000 sq mi).[3] According to Julius Caesar, Gaul was divided into three parts: Gallia Celtica, Belgica, and Aquitania. Archaeologically, the Gauls were bearers of the La Tène culture, which extended across all of Gaul, as well as east to Raetia, Noricum, Pannonia, and southwestern Germania during the 5th to 1st centuries BC.[4] During the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, Gaul fell under Roman rule: Gallia Cisalpina was conquered in 203 BC and Gallia Narbonensis in 123 BC. Gaul was invaded after 120 BC by the Cimbri and the Teutons, who were in turn defeated by the Romans by 103 BC. Julius Caesar finally subdued the remaining parts of Gaul in his campaigns of 58 to 51 BC.

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of France | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

20th century

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||

Roman control of Gaul lasted for five centuries, until the last Roman rump state, the Domain of Soissons, fell to the Franks in AD 486. While the Celtic Gauls had lost their original identities and language during Late Antiquity, becoming amalgamated into a Gallo-Roman culture, Gallia remained the conventional name of the territory throughout the Early Middle Ages, until it acquired a new identity as the Capetian Kingdom of France in the high medieval period. Gallia remains a name of France in modern Greek (Γαλλία) and modern Latin (besides the alternatives Francia and Francogallia).

Name

The Greek and Latin names Galatia (first attested by Timaeus of Tauromenium in the 4th century BC) and Gallia are ultimately derived from a Celtic ethnic term or clan Gal(a)-to-.[5] The Galli of Gallia Celtica were reported to refer to themselves as Celtae by Caesar. Hellenistic folk etymology connected the name of the Galatians (Γαλάται, Galátai) to the supposedly "milk-white" skin (γάλα, gála "milk") of the Gauls.[6] Modern researchers say it is related to Welsh gallu,[7] Cornish: galloes,[8] "capacity, power",[9] thus meaning "powerful people".

Despite superficial similarity, the English term Gaul is unrelated to the Latin Gallia. It stems from the French Gaule, itself deriving from the Old Frankish *Walholant (via a Latinized form *Walula),[10] literally the "Land of the Foreigners/Romans". *Walho- is a reflex of the Proto-Germanic *walhaz, "foreigner, Romanized person", an exonym applied by Germanic speakers to Celts and Latin-speaking people indiscriminately. It is cognate with the names Wales, Cornwall, Wallonia, and Wallachia.[11] The Germanic w- is regularly rendered as gu- / g- in French (cf. guerre "war", garder "ward"), and the historic diphthong au is the regular outcome of al before a following consonant (cf. cheval ~ chevaux). French Gaule or Gaulle cannot be derived from Latin Gallia, since g would become j before a (cf. gamba > jambe), and the diphthong au would be unexplained; the regular outcome of Latin Gallia is Jaille in French, which is found in several western place names, such as, La Jaille-Yvon and Saint-Mars-la-Jaille.[12][13] Proto-Germanic *walha is derived ultimately from the name of the Volcae.[14]

Also unrelated, in spite of superficial similarity, is the name Gael.[16] The Irish word gall did originally mean "a Gaul", i.e. an inhabitant of Gaul, but its meaning was later widened to "foreigner", to describe the Vikings, and later still the Normans.[17] The dichotomic words gael and gall are sometimes used together for contrast, for instance in the 12th-century book Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib.

As adjectives, English has the two variants: Gaulish and Gallic. The two adjectives are used synonymously, as "pertaining to Gaul or the Gauls", although the Celtic language or languages spoken in Gaul is predominantly known as Gaulish.

History

Pre-Roman Gaul

There is little written information concerning the peoples that inhabited the regions of Gaul, save what can be gleaned from coins. Therefore, the early history of the Gauls is predominantly a work in archaeology, and the relationships between their material culture, genetic relationships (the study of which has been aided, in recent years, through the field of archaeogenetics) and linguistic divisions rarely coincide.

Before the rapid spread of the La Tène culture in the 5th to 4th centuries BC, the territory of eastern and southern France already participated in the Late Bronze Age Urnfield culture (c. 12th to 8th centuries BC) out of which the early iron-working Hallstatt culture (7th to 6th centuries BC) would develop. By 500 BC, there is strong Hallstatt influence throughout most of France (except for the Alps and the extreme north-west).

Out of this Hallstatt background, during the 7th and 6th century presumably representing an early form of Continental Celtic culture, the La Tène culture arises, presumably under Mediterranean influence from the Greek, Phoenician, and Etruscan civilizations, spread out in a number of early centers along the Seine, the Middle Rhine and the upper Elbe. By the late 5th century BC, La Tène influence spreads rapidly across the entire territory of Gaul. The La Tène culture developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC) in France, Switzerland, Italy, Austria, southwest Germany, Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia and Hungary. Farther north extended the contemporary pre-Roman Iron Age culture of northern Germany and Scandinavia.

The major source of materials on the Celts of Gaul was Poseidonios of Apamea, whose writings were quoted by Timagenes, Julius Caesar, the Sicilian Greek Diodorus Siculus, and the Greek geographer Strabo.[18]

In the 4th and early 3rd century BC, Gallic clan confederations expanded far beyond the territory of what would become Roman Gaul (which defines usage of the term "Gaul" today), into Pannonia, Illyria, northern Italy, Transylvania and even Asia Minor. By the 2nd century BC, the Romans described Gallia Transalpina as distinct from Gallia Cisalpina. In his Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar distinguishes among three ethnic groups in Gaul: the Belgae in the north (roughly between the Rhine and the Seine), the Celtae in the center and in Armorica, and the Aquitani in the southwest, the southeast being already colonized by the Romans. While some scholars believe the Belgae south of the Somme were a mixture of Celtic and Germanic elements, their ethnic affiliations have not been definitively resolved. One of the reasons is political interference upon the French historical interpretation during the 19th century.

In addition to the Gauls, there were other peoples living in Gaul, such as the Greeks and Phoenicians who had established outposts such as Massilia (present-day Marseille) along the Mediterranean coast.[19] Also, along the southeastern Mediterranean coast, the Ligures had merged with the Celts to form a Celto-Ligurian culture.

Initial contact with Rome

In the 2nd century BC Mediterranean Gaul had an extensive urban fabric and was prosperous. Archeologists know of cities in northern Gaul including the Biturigian capital of Avaricum (Bourges), Cenabum (Orléans), Autricum (Chartres) and the excavated site of Bibracte near Autun in Saône-et-Loire, along with a number of hill forts (or oppida) used in times of war. The prosperity of Mediterranean Gaul encouraged Rome to respond to pleas for assistance from the inhabitants of Massilia, who found themselves under attack by a coalition of Ligures and Gauls.[20] The Romans intervened in Gaul in 154 BC and again in 125 BC.[20] Whereas on the first occasion they came and went, on the second they stayed.[21] In 122 BC Domitius Ahenobarbus managed to defeat the Allobroges (allies of the Salluvii), while in the ensuing year Quintus Fabius Maximus "destroyed" an army of the Arverni led by their king Bituitus, who had come to the aid of the Allobroges.[21] Rome allowed Massilia to keep its lands, but added to its own territories the lands of the conquered tribes.[21] As a direct result of these conquests, Rome now controlled an area extending from the Pyrenees to the lower Rhône river, and in the east up the Rhône valley to Lake Geneva.[22] By 121 BC Romans had conquered the Mediterranean region called Provincia (later named Gallia Narbonensis). This conquest upset the ascendancy of the Gaulish Arverni peoples.

Conquest by Rome

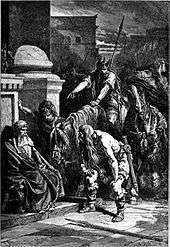

The Roman proconsul and general Julius Caesar pushed his army into Gaul in 58 BC, ostensibly to assist Rome's Gaullish allies against the migrating Helvetii. With the help of various Gallic clans (e.g. the Aedui) he managed to conquer nearly all of Gaul. While their military was just as strong as the Romans, the internal division between the Gallic tribes guaranteed an easy victory for Caesar, and Vercingetorix's attempt to unite the Gauls against Roman invasion came too late.[23][24] Julius Caesar was checked by Vercingetorix at a siege of Gergovia, a fortified town in the center of Gaul. Caesar's alliances with many Gallic clans broke. Even the Aedui, their most faithful supporters, threw in their lot with the Arverni, but the ever-loyal Remi (best known for its cavalry) and Lingones sent troops to support Caesar. The Germani of the Ubii also sent cavalry, which Caesar equipped with Remi horses. Caesar captured Vercingetorix in the Battle of Alesia, which ended the majority of Gallic resistance to Rome.

As many as a million people (probably 1 in 5 of the Gauls) died, another million were enslaved,[25] 300 clans were subjugated and 800 cities were destroyed during the Gallic Wars.[26] The entire population of the city of Avaricum (Bourges) (40,000 in all) were slaughtered.[27] Before Julius Caesar's campaign against the Helvetii (present-day Switzerland), the Helvetians had numbered 263,000, but afterwards only 100,000 remained, most of whom Caesar took as slaves.[28]

Roman Gaul

After Gaul was absorbed as Gallia, a set of Roman provinces, its inhabitants gradually adopted aspects of Roman culture and assimilated, resulting in the distinct Gallo-Roman culture.[29] Citizenship was granted to all in 212 by the Constitutio Antoniniana. From the third to 5th centuries, Gaul was exposed to raids by the Franks. The Gallic Empire, consisting of the provinces of Gaul, Britannia, and Hispania, including the peaceful Baetica in the south, broke away from Rome from 260 to 273. In addition to the large number of natives, Gallia also became home to some Roman citizens from elsewhere and also in-migrating Germanic and Scythian tribes such as the Alans.[30]

The religious practices of inhabitants became a combination of Roman and Celtic practice, with Celtic deities such as Cobannus and Epona subjected to interpretatio romana.[31][32] The imperial cult and Eastern mystery religions also gained a following. Eventually, after it became the official religion of the Empire and paganism became suppressed, Christianity won out in the twilight days of the Western Roman Empire (while the Christianized Eastern Roman Empire lasted another thousand years, until the invasion of Constantinople by the Ottomans in 1453); a small but notable Jewish presence also became established.

The Gaulish language is thought to have survived into the 6th century in France, despite considerable Romanization of the local material culture.[33] The last record of spoken Gaulish deemed to be plausibly credible[33] concerned the destruction by Christians of a pagan shrine in Auvergne "called Vasso Galatae in the Gallic tongue".[34] Coexisting with Latin, Gaulish helped shape the Vulgar Latin dialects that developed into French.[35][36][37][38][39]

The Vulgar Latin in the region of Gallia took on a distinctly local character, some of which is attested in graffiti,[39] which evolved into the Gallo-Romance dialects which include French and its closest relatives. The influence of substrate languages may be seen in graffiti showing sound changes that matched changes that had earlier occurred in the indigenous languages, especially Gaulish.[39] The Vulgar Latin in the north of Gaul evolved into the langues d'oil and Franco-Provencal, while the dialects in the south evolved into the modern Occitan and Catalan tongues. Other languages held to be "Gallo-Romance" include the Gallo-Italic languages and the Rhaeto-Romance languages.

Frankish Gaul

Following the Frankish victory at the Battle of Soissons in AD 486, Gaul (except for Septimania) came under the rule of the Merovingians, the first kings of France. Gallo-Roman culture, the Romanized culture of Gaul under the rule of the Roman Empire, persisted particularly in the areas of Gallia Narbonensis that developed into Occitania, Gallia Cisalpina and to a lesser degree, Aquitania. The formerly Romanized north of Gaul, once it had been occupied by the Franks, would develop into Merovingian culture instead. Roman life, centered on the public events and cultural responsibilities of urban life in the res publica and the sometimes luxurious life of the self-sufficient rural villa system, took longer to collapse in the Gallo-Roman regions, where the Visigoths largely inherited the status quo in the early 5th century. Gallo-Roman language persisted in the northeast into the Silva Carbonaria that formed an effective cultural barrier, with the Franks to the north and east, and in the northwest to the lower valley of the Loire, where Gallo-Roman culture interfaced with Frankish culture in a city like Tours and in the person of that Gallo-Roman bishop confronted with Merovingian royals, Gregory of Tours.

Massalia (modern Marseille) silver coin with Greek legend, 5th–1st century BC.

Massalia (modern Marseille) silver coin with Greek legend, 5th–1st century BC. Gold coins of the Gaul Parisii, 1st century BC, (Cabinet des Médailles, Paris).

Gold coins of the Gaul Parisii, 1st century BC, (Cabinet des Médailles, Paris).- Roman silver Denarius with the head of captive Gaul 48 BC, following the campaigns of Julius Caesar.

Gauls

Social structure, indigenous nation and clans

The Druids were not the only political force in Gaul, however, and the early political system was complex, if ultimately fatal to the society as a whole. The fundamental unit of Gallic politics was the clan, which itself consisted of one or more of what Caesar called pagi. Each clan had a council of elders, and initially a king. Later, the executive was an annually-elected magistrate. Among the Aedui, a clan of Gaul, the executive held the title of Vergobret, a position much like a king, but his powers were held in check by rules laid down by the council.

The regional ethnic groups, or pagi as the Romans called them (singular: pagus; the French word pays, "region" [a more accurate translation is 'country'], comes from this term), were organized into larger multi-clan groups, which the Romans called civitates. These administrative groupings would be taken over by the Romans in their system of local control, and these civitates would also be the basis of France's eventual division into ecclesiastical bishoprics and dioceses, which would remain in place—with slight changes—until the French Revolution.

Although the individual clans were moderately stable political entities, Gaul as a whole tended to be politically divided, there being virtually no unity among the various clans. Only during particularly trying times, such as the invasion of Caesar, could the Gauls unite under a single leader like Vercingetorix. Even then, however, the faction lines were clear.

The Romans divided Gaul broadly into Provincia (the conquered area around the Mediterranean), and the northern Gallia Comata ("free Gaul" or "long haired Gaul"). Caesar divided the people of Gallia Comata into three broad groups: the Aquitani; Galli (who in their own language were called Celtae); and Belgae. In the modern sense, Gaulish peoples are defined linguistically, as speakers of dialects of the Gaulish language. While the Aquitani were probably Vascons, the Belgae would thus probably be a mixture of Celtic and Germanic elements.

Julius Caesar, in his book, The Gallic Wars, comments:

All Gaul is divided into three parts, one of which the Belgae inhabit, the Aquitani another, those who in their own language are called Celts, in our Gauls, the third. All these differ from each other in language, customs and laws. The river Garonne separates the Gauls from the Aquitani; the Marne and the Seine separate them from the Belgae. Of all these, the Belgae are the bravest, because they are furthest from the civilization and refinement of [our] Province, and merchants least frequently resort to them, and import those things which tend to effeminate the mind; and they are the nearest to the Germans, who dwell beyond the Rhine, with whom they are continually waging war; for which reason the Helvetii also surpass the rest of the Gauls in valor, as they contend with the Germans in almost daily battles, when they either repel them from their own territories, or themselves wage war on their frontiers. One part of these, which it has been said that the Gauls occupy, takes its beginning at the river Rhone; it is bounded by the river Garonne, the ocean, and the territories of the Belgae; it borders, too, on the side of the Sequani and the Helvetii, upon the river Rhine, and stretches toward the north. The Belgae rises from the extreme frontier of Gaul, extend to the lower part of the river Rhine; and look toward the north and the rising sun. Aquitania extends from the river Garonne to the Pyrenaean mountains and to that part of the ocean which is near Spain: it looks between the setting of the sun, and the north star. .[40]

Religion

The Gauls practiced a form of animism, ascribing human characteristics to lakes, streams, mountains, and other natural features and granting them a quasi-divine status. Also, worship of animals was not uncommon; the animal most sacred to the Gauls was the boar[41] which can be found on many Gallic military standards, much like the Roman eagle.

Their system of gods and goddesses was loose, there being certain deities which virtually every Gallic person worshipped, as well as clan and household gods. Many of the major gods were related to Greek gods; the primary god worshipped at the time of the arrival of Caesar was Teutates, the Gallic equivalent of Mercury. The "ancestor god" of the Gauls was identified by Julius Caesar in his Commentarii de Bello Gallico with the Roman god Dis Pater.[42]

Perhaps the most intriguing facet of Gallic religion is the practice of the Druids. The druids presided over human or animal sacrifices that were made in wooded groves or crude temples. They also appear to have held the responsibility for preserving the annual agricultural calendar and instigating seasonal festivals which corresponded to key points of the lunar-solar calendar. The religious practices of druids were syncretic and borrowed from earlier pagan traditions, with probably indo-European roots. Julius Caesar mentions in his Gallic Wars that those Celts who wanted to make a close study of druidism went to Britain to do so. In a little over a century later, Gnaeus Julius Agricola mentions Roman armies attacking a large druid sanctuary in Anglesey in Wales. There is no certainty concerning the origin of the druids, but it is clear that they vehemently guarded the secrets of their order and held sway over the people of Gaul. Indeed, they claimed the right to determine questions of war and peace, and thereby held an "international" status. In addition, the Druids monitored the religion of ordinary Gauls and were in charge of educating the aristocracy. They also practiced a form of excommunication from the assembly of worshippers, which in ancient Gaul meant a separation from secular society as well. Thus the Druids were an important part of Gallic society. The nearly complete and mysterious disappearance of the Celtic language from most of the territorial lands of ancient Gaul, with the exception of Brittany France, can be attributed to the fact that Celtic druids refused to allow the Celtic oral literature or traditional wisdom to be committed to the written letter.[43]

See also

- Ambiorix

- Asterix—a French comic about Gaul and Rome, mainly set in 50 BC

- Bog body

- Braccae—trousers, typical Gallic dress

- Cisalpine Gaul

- Galatia

- Lugdunum

- Roman Republic

- Roman Villas in Northwestern Gaul

References

- English: /ˈɡæliə/

- Polybius: Histories

- Arrowsmith, Aaron (1832). A Grammar of Ancient Geography,: Compiled for the Use of King's College School. Hansard London 1832. p. 50. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

gallia .

- Bisdent, Bisdent (28 April 2011). "Gaul". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Birkhan 1997, p. 48.

- "The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville" p. 198 Cambridge University Press 2006 Stephen A. Barney, W. J. Lewis, J. A. Beach and Oliver Berghof.

- "gallu". Google Translate. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Howlsedhes Services. "Gerlyver Sempel". Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- Pierre-Yves Lambert, La langue gauloise, éditions Errance, 1994, p. 194.

- Ekblom, R., "Die Herkunft des Namens La Gaule" in: Studia Neophilologica, Uppsala, XV, 1942-43, nos. 1-2, p. 291-301.

- Sjögren, Albert, Le nom de "Gaule", in Studia Neophilologica, Vol. 11 (1938/39) pp. 210–214.

- Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (OUP 1966), p. 391.

- Nouveau dictionnaire étymologique et historique (Larousse 1990), p. 336.

- Koch 2006, p. 532.

- Koch 2006, pp. 775–776.

- Gael is derived from Old Irish Goidel (borrowed, in turn, in the 7th century AD from Primitive Welsh Guoidel—spelled Gwyddel in Middle Welsh and Modern Welsh—likely derived from a Brittonic root *Wēdelos meaning literally "forest person, wild man")[15]

- Linehan, Peter; Janet L. Nelson (2003). The Medieval World. 10. Routledge. p. 393. ISBN 978-0-415-30234-0.

- Berresford Ellis, Peter (1998). The Celts: A History. Caroll & Graf. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-7867-1211-2.

- Dietler, Michael (2010). Archaeologies of Colonialism: Consumption, Entanglement, and Violence in Ancient Mediterranean France. Berkeley, CA.

- Drinkwater 2014, p. 5.

- Drinkwater 2014, p. 6.

- Drinkwater 2014, p. 6. "[...] the most important outcome of this series of campaigns was the direct annexation by Rome of a huge area extending from the Pyrenees to the lower Rhône, and up the Rhône valley to Lake Geneva."

- "France: The Roman conquest". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

Because of chronic internal rivalries, Gallic resistance was easily broken, though Vercingetorix’s Great Rebellion of 52 bc had notable successes.

- "Julius Caesar: The first triumvirate and the conquest of Gaul". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

Indeed, the Gallic cavalry was probably superior to the Roman, horseman for horseman. Rome’s military superiority lay in its mastery of strategy, tactics, discipline, and military engineering. In Gaul, Rome also had the advantage of being able to deal separately with dozens of relatively small, independent, and uncooperative states. Caesar conquered these piecemeal, and the concerted attempt made by a number of them in 52 BC to shake off the Roman yoke came too late.

- Plutarch, Caesar 22.

- Tibbetts, Jann (2016-07-30). 50 Great Military Leaders of All Time. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. ISBN 9789385505669.

- Seindal, René (28 August 2003). "Julius Caesar, Romans [The Conquest of Gaul - part 4 of 11] (Photo Archive)". Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Serghidou, Anastasia (2007). Fear of slaves, fear of enslavement in the ancient Mediterranean. Besançon: Presses Univ. Franche-Comté. p. 50. ISBN 978-2848671697. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- A recent survey is G. Woolf, Becoming Roman: The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul (Cambridge University Press) 1998.

- Bachrach, Bernard S. (1972). Merovingian Military Organization, 481-751. U of Minnesota Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780816657001.

- Pollini, J. (2002). Gallo-Roman Bronzes and the Process of Romanization: The Cobannus Hoard. Monumenta Graeca et Romana. 9. Leiden: Brill.

- Oaks, L.S. (1986). "The goddess Epona: concepts of sovereignty in a changing landscape". Pagan Gods and Shrines of the Roman Empire.

- Laurence Hélix (2011). Histoire de la langue française. Ellipses Edition Marketing S.A. p. 7. ISBN 978-2-7298-6470-5.

Le déclin du Gaulois et sa disparition ne s'expliquent pas seulement par des pratiques culturelles spécifiques: Lorsque les Romains conduits par César envahirent la Gaule, au 1er siecle avant J.-C., celle-ci romanisa de manière progressive et profonde. Pendant près de 500 ans, la fameuse période gallo-romaine, le gaulois et le latin parlé coexistèrent; au VIe siècle encore; le temoignage de Grégoire de Tours atteste la survivance de la langue gauloise.

- Hist. Franc., book I, 32 Veniens vero Arvernos, delubrum illud, quod Gallica lingua Vasso Galatæ vocant, incendit, diruit, atque subvertit. And coming to Clermont [to the Arverni] he set on fire, overthrew and destroyed that shrine which they call Vasso Galatæ in the Gallic tongue.

- Henri Guiter, "Sur le substrat gaulois dans la Romania", in Munus amicitae. Studia linguistica in honorem Witoldi Manczak septuagenarii, eds., Anna Bochnakowa & Stanislan Widlak, Krakow, 1995.

- Eugeen Roegiest, Vers les sources des langues romanes: Un itinéraire linguistique à travers la Romania (Leuven, Belgium: Acco, 2006), 83.

- Savignac, Jean-Paul (2004). Dictionnaire Français-Gaulois. Paris: La Différence. p. 26.

- Matasovic, Ranko (2007). "Insular Celtic as a Language Area". Papers from the Workship within the Framework of the XIII International Congress of Celtic Studies. The Celtic Languages in Contact: 106.

- Adams, J. N. (2007). "Chapter V -- Regionalisms in provincial texts: Gaul". The Regional Diversification of Latin 200 BC – AD 600. Cambridge. p. 279–289. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511482977. ISBN 9780511482977.

- Caesar, Julius; McDevitte, W. A.; Bohn, W. S., trans (1869). The Gallic Wars. New York: Harper. p. 9. ISBN 978-1604597622. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- MacCulloch, John Arnott (1911). The Religion of the Ancient Celts. Edinburgh: Clark. p. 22. ISBN 978-1508518518. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Warner, Marina; Burn, Lucilla (2003). World of Myths, Vol. 1. London: British Museum. p. 382. ISBN 978-0714127835. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- Kendrick, Thomas D. (1966). The Druids: A study in Keltic prehistory (1966 ed.). New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. p. 78.

Sources

- Birkhan, H. (1997). Die Kelten. Vienna.

- Drinkwater, John Frederick (2014) [1983]. "Conquest and Pacification". Roman Gaul: The Three Provinces, 58 BC-AD 260. Routledge Revivals. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1317750741.

- Koch, John Thomas (2006). Celtic culture: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-440-7.