Passport

A passport is a travel document, usually issued by a country's government to its citizens, that certifies the identity and nationality of its holder primarily for the purpose of international travel.[1] Standard passports may contain information such as the holder's name, place and date of birth, photograph, signature, and other relevant identifying information.

Many countries have either begun issuing or plan to issue biometric passports that contains an embedded microchip, making them machine-readable and difficult to counterfeit.[1] As of January 2019, there were over 150 jurisdictions issuing e-passports.[2] Previously issued non-biometric machine-readable passports usually remain valid until their respective expiration dates.

.jpg)

A passport holder is normally entitled to enter the country that issued the passport, though some people entitled to a passport may not be full citizens with right of abode (e.g. American nationals or British nationals). A passport does not of itself create any rights in the country being visited or obligate the issuing country in any way, such as providing consular assistance. Some passports attest to the bearer having a status as a diplomat or other official, entitled to rights and privileges such as immunity from arrest or prosecution.[1]

Many countries normally allow entry to holders of passports of other countries, sometimes requiring a visa also to be obtained, but this is not an automatic right. Many other additional conditions, such as not being likely to become a public charge for financial or other reasons, and the holder not having been convicted of a crime, may apply.[3] Where a country does not recognise another, or is in dispute with it, it may prohibit the use of their passport for travel to that other country, or may prohibit entry to holders of that other country's passports, and sometimes to others who have, for example, visited the other country. Some individuals are subject to sanctions which deny them entry into particular countries.

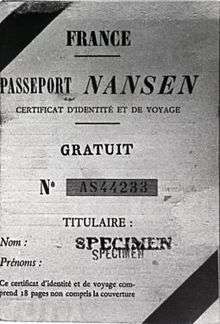

Some countries and international organisations issue travel documents which are not standard passports, but enable the holder to travel internationally to countries that recognise the documents. For example, stateless persons are not normally issued a national passport, but may be able to obtain a refugee travel document or the earlier "Nansen passport" which enables them to travel to countries which recognise the document, and sometimes to return to the issuing country.

Passports may be requested in other circumstances to confirm identification such as checking into a hotel or when changing money to a local currency. Passports and other travel documents have an expiry date, after which it is no longer recognised, but it is recommended that a passport is valid for at least six months as many airlines deny boarding to passengers whose passport has a shorter expiry date, even if the destination country may not have such a requirement.

History

One of the earliest known references to paperwork that served in a role similar to that of a passport is found in the Hebrew Bible. Nehemiah 2:7–9, dating from approximately 450 BC, states that Nehemiah, an official serving King Artaxerxes I of Persia, asked permission to travel to Judea; the king granted leave and gave him a letter "to the governors beyond the river" requesting safe passage for him as he traveled through their lands.

Arthashastra mentions the first passport and passbooks in world history. According to the text, the superintendent of passports must issue sealed passes before one could enter or leave the countryside.[4]

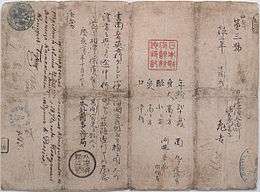

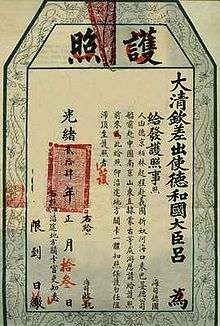

Passports were an important part of the Chinese bureaucracy as early as the Western Han, if not in the Qin Dynasty. They required such details as age, height, and bodily features.[5] These passports (zhuan) determined a person's ability to move throughout imperial counties and through points of control. Even children needed passports, but those of one year or less who were in their mother's care might not have needed them.[5]

In the medieval Islamic Caliphate, a form of passport was the bara'a, a receipt for taxes paid. Only people who paid their zakah (for Muslims) or jizya (for dhimmis) taxes were permitted to travel to different regions of the Caliphate; thus, the bara'a receipt was a "basic passport."[6]

Etymological sources show that the term "passport" is from a medieval document that was required in order to pass through the gate (or "porte") of a city wall or to pass through a territory.[7][8] In medieval Europe, such documents were issued to foreign travellers by local authorities (as opposed to local citizens, as is the modern practice) and generally contained a list of towns and cities the document holder was permitted to enter or pass through. On the whole, documents were not required for travel to sea ports, which were considered open trading points, but documents were required to travel inland from sea ports.[9]

King Henry V of England is credited with having invented what some consider the first passport in the modern sense, as a means of helping his subjects prove who they were in foreign lands. The earliest reference to these documents is found in a 1414 Act of Parliament.[10][11] In 1540, granting travel documents in England became a role of the Privy Council of England, and it was around this time that the term "passport" was used. In 1794, issuing British passports became the job of the Office of the Secretary of State.[10] The 1548 Imperial Diet of Augsburg required the public to hold imperial documents for travel, at the risk of permanent exile.[12]

A rapid expansion of railway infrastructure and wealth in Europe beginning in the mid-nineteenth century led to large increases in the volume of international travel and a consequent unique dilution of the passport system for approximately thirty years prior to World War I. The speed of trains, as well as the number of passengers that crossed multiple borders, made enforcement of passport laws difficult. The general reaction was the relaxation of passport requirements.[13] In the later part of the nineteenth century and up to World War I, passports were not required, on the whole, for travel within Europe, and crossing a border was a relatively straightforward procedure. Consequently, comparatively few people held passports.

During World War I, European governments introduced border passport requirements for security reasons, and to control the emigration of people with useful skills. These controls remained in place after the war, becoming a standard, though controversial, procedure. British tourists of the 1920s complained, especially about attached photographs and physical descriptions, which they considered led to a "nasty dehumanisation".[14] The British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act was passed in 1914, clearly defining the notions of citizenship and creating a booklet form of the passport.

In 1920, the League of Nations held a conference on passports, the Paris Conference on Passports & Customs Formalities and Through Tickets.[15] Passport guidelines and a general booklet design resulted from the conference,[16] which was followed up by conferences in 1926 and 1927.[17]

While the United Nations held a travel conference in 1963, no passport guidelines resulted from it. Passport standardization came about in 1980, under the auspices of the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). ICAO standards include those for machine-readable passports.[18] Such passports have an area where some of the information otherwise written in textual form is written as strings of alphanumeric characters, printed in a manner suitable for optical character recognition. This enables border controllers and other law enforcement agents to process these passports more quickly, without having to input the information manually into a computer. ICAO publishes Doc 9303 Machine Readable Travel Documents, the technical standard for machine-readable passports.[19] A more recent standard is for biometric passports. These contain biometrics to authenticate the identity of travellers. The passport's critical information is stored on a tiny RFID computer chip, much like information stored on smartcards. Like some smartcards, the passport booklet design calls for an embedded contactless chip that is able to hold digital signature data to ensure the integrity of the passport and the biometric data.

Issuances

Historically, legal authority to issue passports is founded on the exercise of each country's executive discretion (or Crown prerogative). Certain legal tenets follow, namely: first, passports are issued in the name of the state; second, no person has a legal right to be issued a passport; third, each country's government, in exercising its executive discretion, has complete and unfettered discretion to refuse to issue or to revoke a passport; and fourth, that the latter discretion is not subject to judicial review. However, legal scholars including A.J. Arkelian have argued that evolutions in both the constitutional law of democratic countries and the international law applicable to all countries now render those historical tenets both obsolete and unlawful.[20][21]

Under some circumstances some countries allow people to hold more than one passport document. This may apply, for example, to people who travel a lot on business, and may need to have, say, a passport to travel on while another is awaiting a visa for another country. The UK for example may issue a second passport if the applicant can show a need and supporting documentation, such as a letter from an employer.

National conditions

Today, most countries issue individual passports to applying citizens, including children, with only a few still issuing family passports (see below under "Types") or including children on a parent's passport (most countries having switched to individual passports in the early to mid-20th century). When passport holders apply for a new passport (commonly, due to expiration of the previous passport, insufficient validity for entry to some countries or lack of blank pages), they may be required to surrender the old passport for invalidation. In some circumstances an expired passport is not required to be surrendered or invalidated (for example, if it contains an unexpired visa).

Under the law of most countries, passports are government property, and may be limited or revoked at any time, usually on specified grounds, and possibly subject to judicial review.[22] In many countries, surrender of one's passport is a condition of granting bail in lieu of imprisonment for a pending criminal trial due to flight risk.[23]

Each country sets its own conditions for the issue of passports.[24] For example, Pakistan requires applicants to be interviewed before a Pakistani passport will be granted.[25] When applying for a passport or a national ID card, all Pakistanis are required to sign an oath declaring Mirza Ghulam Ahmad to be an impostor prophet and all Ahmadis to be non-Muslims.[26]

Some countries limit the issuance of passports, where incoming and outgoing international travels are highly regulated, such as North Korea, where ordinary passports are the privilege of a very small number of people trusted by the government. Other countries put requirements on some citizens in order to be granted passports, such as Finland, where male citizens aged 18–30 years must prove that they have completed, or are exempt from, their obligatory military service to be granted an unrestricted passport; otherwise a passport is issued valid only until the end of their 28th year, to ensure that they return to carry out military service.[27] Other countries with obligatory military service, such as South Korea and Syria, have similar requirements, e.g. South Korean passport and Syrian passport.[28]

National status

Passports contain a statement of the nationality of the holder. In most countries, only one class of nationality exists, and only one type of ordinary passport is issued. However, several types of exceptions exist:

Multiple classes of nationality in a single country

The United Kingdom has a number of classes of United Kingdom nationality due to its colonial history. As a result, the UK issues various passports which are similar in appearance but representative of different nationality statuses which, in turn, has caused foreign governments to subject holders of different UK passports to different entry requirements.

Multiple types of passports, one nationality

The People's Republic of China (PRC) authorizes its Special Administrative Regions of Hong Kong and Macau to issue passports to their permanent residents with Chinese nationality under the "one country, two systems" arrangement. Visa policies imposed by foreign authorities on Hong Kong and Macau permanent residents holding such passports are different from those holding ordinary passports of the People's Republic of China. A Hong Kong Special Administrative Region passport (HKSAR passport) permits visa-free access to many more countries than ordinary PRC passports.

The three constituent countries of the Danish Realm have a common nationality. Denmark proper is a member of the European Union, but Greenland and Faroe Islands are not. Danish citizens residing in Greenland or Faroe Islands can choose between holding a Danish EU passport and a Greenlandic or Faroese non-EU Danish passport.

Special nationality class through investment

In rare instances a nationality is available through investment. Some investors have been described in Tongan passports as 'a Tongan protected person', a status which does not necessarily carry with it the right of abode in Tonga.[29]

Passports without sovereign territory

Several entities without a sovereign territory issue documents described as passports, most notably Iroquois League,[30][31] the Aboriginal Provisional Government in Australia and the Sovereign Military Order of Malta.[32] Such documents are not necessarily accepted for entry into a country.

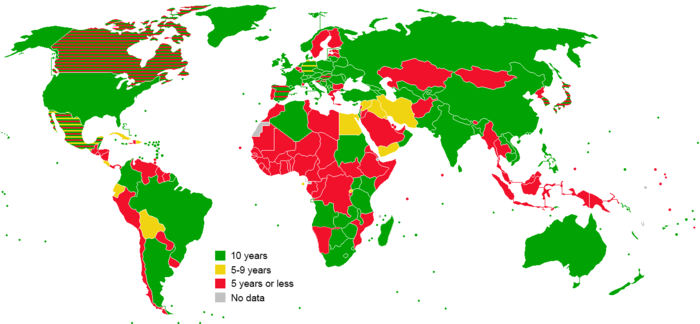

Validity

Passports have a limited validity, usually between 5 and 10 years.

Many countries require passports to be valid for a minimum of six months beyond the planned date of departure, as well as having at least two to four blank pages.[33] It is recommended that a passport be valid for at least six months from the departure date as many airlines deny boarding to passengers whose passport has a shorter expiry date, even if the destination country does not have such a requirement for incoming visitors.

Value

One method to measure the 'value' of a passport is to calculate its 'visa-free score' (VFS), which is the number of countries that allow the holder of that passport entry for general tourism without requiring a visa.[34] As of 1 July 2019, the strongest and weakest passports are as follows:

| Strongest passports | Weakest passports | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | VFS | Country / countries | Rank | VFS | Country / countries | |

| 1 | 189 | Japan, Singapore | 100 | 41 | Kosovo | |

| 2 | 187 | Finland, Germany, South Korea | 101 | 39 | Bangladesh, Eritrea, Iran, Lebanon, North Korea | |

| 3 | 186 | Denmark, Italy, Luxembourg | 102 | 38 | Nepal | |

| 4 | 185 | France, Spain, Sweden | 103 | 37 | Libya, Palestine, Sudan | |

| 5 | 184 | Austria, Netherlands, Portugal, Switzerland | 104 | 33 | Yemen | |

| 6 | 183 | Belgium, Canada, Greece, Republic of Ireland, Norway, United Kingdom, United States | 105 | 31 | Somalia | |

| 7 | 182 | Malta | 106 | 30 | Pakistan | |

| 8 | 181 | Czech Republic | 107 | 29 | Syria | |

| 9 | 180 | Australia, Iceland, Lithuania, New Zealand | 108 | 27 | Iraq | |

| 10 | 179 | Latvia, Slovakia, Slovenia | 109 | 25 | Afghanistan | |

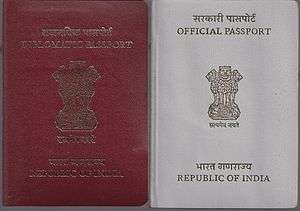

Types

A rough standardization exists in types of passports throughout the world, although passport types, number of pages, and definitions can vary by country.

Full passports

Left to right: diplomatic, official, and regular passport from India. Each passport type has a different cover colour. |

- Passport (also called ordinary, regular, or tourist passport) – The most common form of passport, issued to individual citizens and other nationals (most nations stopped issuing family passports several decades ago due to logistical and security reasons).

- Official passport (also called Service passport) – Issued to government employees for work-related travel, and their accompanying dependants.

- Diplomatic passport – Issued to diplomats of a country and their accompanying dependents for official international travel and residence. Accredited diplomats of certain grades may be granted diplomatic immunity by a host country, but this is not automatically conferred by holding a diplomatic passport. Any diplomatic privileges apply in the country to which the diplomat is accredited; elsewhere diplomatic passport holders must adhere to the same regulations and travel procedures as are required of other nationals of their country. Holding a diplomatic passport in itself does not accord any specific privileges. At some airports, there are separate passport checkpoints for diplomatic passport holders.

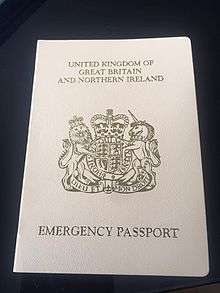

- Emergency passport (also called temporary passport) – Issued to persons whose passports were lost or stolen without time to obtain a replacement, e.g. someone abroad and needing to fly home within a few days. These passports are intended for very short time durations, e.g. one way travel back to home country, and will naturally have much shorter validity periods than regular passports. Laissez-passer are also used for this purpose.[35]

British Emergency Passport

British Emergency Passport - Collective passport – Issued to defined groups for travel together to particular destinations, such as a group of school children on a school trip.[36]

- Family passport – Issued to an entire family. There is one passport holder, who may travel alone or with other family members included in the passport. A family member who is not the passport holder cannot use the passport for travel without the passport holder. Few countries now issue family passports; for example, all the EU countries, Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom, among numerous other countries, require each child to have their own passport.[37]

Non-citizen passports

Latvia and Estonia

Non-citizens in Latvia and Estonia are individuals, primarily of Russian or Ukrainian ethnicity, who are not citizens of Latvia or Estonia but whose families have resided in the area since the Soviet era, and thus have the right to a non-citizen passport issued by the Latvian government as well as other specific rights. Approximately two thirds of them are ethnic Russians, followed by ethnic Belarusians, ethnic Ukrainians, ethnic Poles and ethnic Lithuanians.[38][39]

Non-citizens in the two countries are issued special non-citizen passports[40][41] as opposed to regular passports issued by the Estonian and Latvian authorities to citizens.

American Samoa

Although all U.S. citizens are also U.S. nationals, the reverse is not true. As specified in 8 U.S.C. § 1408, a person whose only connection to the U.S. is through birth in an outlying possession (which is defined in 8 U.S.C. § 1101 as American Samoa and Swains Island, the latter of which is administered as part of American Samoa), or through descent from a person so born, acquires U.S. nationality but not U.S. citizenship. This was formerly the case in a few other current or former U.S. overseas possessions, i.e. the Panama Canal Zone and Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.[42]

The U.S. passport issued to non-citizen nationals contains the endorsement code 9 which states: "THE BEARER IS A UNITED STATES NATIONAL AND NOT A UNITED STATES CITIZEN." on the annotations page.[43]

Non-citizen U.S. nationals may reside and work in the United States without restrictions, and may apply for citizenship under the same rules as resident aliens. Like resident aliens, they are not presently allowed by any U.S. state to vote in federal or state elections, although, as with resident aliens, there is no constitutional prohibition against their doing so.

United Kingdom

Due to the complexity of British nationality law, the United Kingdom has six variants of British nationality. Out of these variants, however, only the status known as British citizen grants the right of abode in a particular country or territory (the United Kingdom) while others do not. Hence, the UK issues British passports to those who are British nationals but not British citizens, which include British Overseas Territories citizens, British Overseas citizens, British subjects, British Nationals (Overseas) and British Protected Persons.[44]

Andorra

Children born in Andorra to foreign residents who have not yet resided in the country for a minimum of 10 years are provided a provisional passport. Once the child reaches 18 years old he or she must confirm their nationality to the Government.

Other types of travel documents

- Laissez-passer – Issued by national governments or international organizations (such as the U.N.) as emergency passports, travel on humanitarian grounds, or for official travel.

- Interpol Travel Document – Issued by Interpol to police officers for official travel, allowing them to bypass certain visa restrictions in certain member states when investigating transnational crime.

- Certificate of identity (also called alien's passport, or informally, a Travel Document) – Issued under certain circumstances, such as statelessness, to non-citizen residents. An example is the "Nansen passport" (pictured). Sometimes issued as an internal passport to non-residents.

- Refugee travel document – Issued to a refugee by the state in which she or he currently resides allowing them to travel outside that state and to return. Made necessary because refugees are unlikely to be able to obtain passports from their state of nationality.

- Permits. Many types of travel permit exist around the world. Some, like the U.S. Re-entry Permit and Japan Re-entry Permit, allow residents of those countries who are unable to obtain a permanent residence to travel outside the country and return. Others, like the Bangladesh Special Passport,[45] the Two-way permit, and the Taibaozheng (Taiwan Compatriot Entry Permit), are used for travel to and from specific countries or locations, for example to travel between mainland China and Macau, or between Taiwan and China.

- Chinese Travel Document – Issued by the People's Republic of China to Chinese citizens in lieu of a passport.

- Hajj passport – a special passport used only for Hajj and Umrah pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina, Saudi Arabia.

- A diplomatic visa in combination with a regular or diplomatic passport.[46]

Intra-sovereign territory travel that requires passports

For some countries, passports are required for some types of travel between their sovereign territories. Three examples of this are:

- Hong Kong and Macau, both Chinese special administrative regions (SARs), have their own immigration control systems different from each other and mainland China. Travelling between the three is technically not international, so residents of the three locations do not use passports to travel between the three places, instead using other documents, such as the Mainland Travel Permit (for the people of Hong Kong and Macau). Foreign visitors are required to present their passports with applicable visas at the immigration control points.

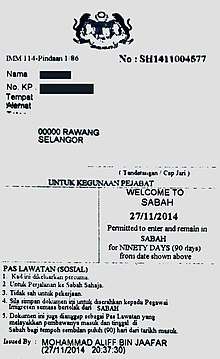

- Malaysia, where an arrangement was agreed upon during the formation of the country, the East Malaysian states of Sabah and Sarawak were allowed to retain their respective immigration control systems. Therefore, a passport is required for foreign visitors when travelling from Peninsular Malaysia to East Malaysia, as well as moving between Sabah and Sarawak. For social/business visits not more than 3 months, Peninsular Malaysians are required to produce a MyKad or, for children below 12 years a birth certificate, and obtain a special immigration printout form to be kept until departure.[47] However, one may present a Malaysian passport or a Restricted Travel Document and get an entry stamp on the travel document to avoid the hassle of keeping an extra sheet of paper. For other purposes, Peninsular Malaysians are required to have a long-term residence permit along with a passport or a Restricted Travel Document.

- Norfolk Island, one of Australia's external, self-governing territories, has its own immigration controls. Until 2018, Australian and New Zealand citizens travelling to the territory were required to carry a passport, or an Australian Document of Identity, while people of other nationalities must also have a valid Australian visa and/or Permanent Resident of Norfolk Island visa.[48]

Internal passports

Internal passports are issued by some countries as an identity document. An example is the internal passport of Russia or certain other post-Soviet countries dating back to imperial times. Some countries use internal passports for controlling migration within a country. In some countries, the international passport or passport for travel abroad is a second passport, in addition to the internal passport, required for a citizen to travel abroad within the country of residence. Separate passports for travel abroad existed or exist in the following countries:

- Russia: see Internal passport of Russia

- Ukraine: see Ukrainian identity card#Previous internal passport

- In the Soviet Union, there were several types of international passport: an ordinary one, a civil service passport, a diplomatic passport, and a sailor's passport. See Passport system in the Soviet Union.

- Countries of the Eastern Bloc had a system of internal/international passports similar to that of the Soviet Union.

Designs and format

International Civil Aviation Organization standards

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) issues passport standards which are treated as recommendations to national governments. The size of passport booklets normally complies with the ISO/IEC 7810 ID-3 standard, which specifies a size of 125 × 88 mm (4.921 × 3.465 in). This size is the B7 format. Passport cards are issued to the ID-1 (credit card sized) standard.[49][50][51][52][53]

- A standard passport booklet format includes the cover, which contains the name of the issuing country, a national symbol, a description of the document (e.g., passport, diplomatic passport), and a biometric passport symbol, if applicable. Inside, there is a title page, also naming the country. A data page follows, containing information about the bearer and the issuing authority. There are blank pages for visas, and to stamp for entries and exit. Passports have numerical or alphanumerical designators ("serial number") assigned by the issuing authority.

- Machine-readable passport standards have been issued by the ICAO,[55] with an area set aside where most of the information written as text is also printed in a manner suitable for optical character recognition.

- Biometric passports (or e-passports) have an embedded contactless chip in order to conform to ICAO standards. These chips contain data about the passport bearer, a photographic portrait in digital format, and data about the passport itself. Many countries now issue biometric passports, in order to speed up clearance through immigration and the prevention of identity fraud. These reasons are disputed by privacy advocates.[56][57]

Common designs

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Common-design passport groups. |

Passport booklets from almost all countries around the world display the national coat of arms of the issuing country on the front cover. The United Nations keeps a record of national coats of arms, but displaying a coat of arms is not an internationally recognized requirement for a passport.

There are several groups of countries that have, by mutual agreement, adopted common designs for their passports:

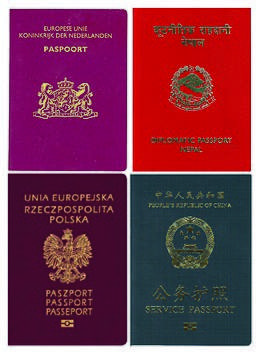

- The European Union. The design and layout of passports of the member states of the European Union are a result of consensus and recommendation, rather than of directive.[58] Passports are issued by member states and may consist of either the usual passport booklet or the newer passport card format. The covers of ordinary passport booklets are burgundy-red (except for Croatia which has a blue cover), with "European Union" written in the national language or languages. Below that are the name of the country, the national coat of arms, the word or words for "passport", and, at the bottom, the symbol for a biometric passport. The data page can be at the front or at the back of a passport booklet and there are significant design differences throughout to indicate which member state is the issuer.[note 1] Member states that participate in the Schengen Agreement have agreed that their e-passports should contain fingerprint information in the chip.[59]

- In 2006, the members of the CA-4 Treaty (Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua) adopted a common-design passport, called the Central American passport, following a design already in use by Nicaragua and El Salvador since the mid-1990s. It features a navy-blue cover with the words "América Central" and a map of Central America, and with the territory of the issuing country highlighted in gold (in place of the individual nations' coats of arms). At the bottom of the cover are the name of the issuing country and the passport type.

- The members of the Andean Community of Nations (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru) began to issue commonly designed passports in 2005. Specifications for the common passport format were outlined in an Andean Council of Foreign Ministers meeting in 2002.[60] Previously-issued national passports will be valid until their expiry dates. Andean passports are bordeaux (burgundy-red), with words in gold. Centered above the national seal of the issuing country is the name of the regional body in Spanish (Comunidad Andina). Below the seal is the official name of the member country. At the bottom of the cover is the Spanish word "pasaporte" along with the English "passport". Venezuela had issued Andean passports, but has subsequently left the Andean Community, so they will no longer issue Andean passports.

- The Union of South American Nations signaled an intention to establish a common passport design, but it appears that implementation will take many years.

- The member states of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) recently began issuing passports with a common design. It features the CARICOM symbol along with the national coat of arms and name of the member state, rendered in a CARICOM official language (English, French, Dutch). The member states which use the common design are Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago. There was a movement by the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) to issue a common designed passport, but the implementation of the CARICOM passport made that redundant, and it was abandoned.

Request page

Passports sometimes contain a message, usually near the front, requesting that the passport's bearer be allowed to pass freely, and further requesting that, in the event of need, the bearer be granted assistance. The message is sometimes made in the name of the government or the head of state, and may be written in more than one language, depending on the language policies of the issuing authority.

Languages

In 1920, an international conference on passports and through tickets held by the League of Nations recommended that passports be issued in the French language, historically the language of diplomacy, and one other language.[61] Currently, the ICAO recommends that passports be issued in English and French, or in the national language of the issuing country and in either English or French. Many European countries use their national language, along with English and French.

Some unusual language combinations are:

- National passports of the European Union bear all of the official languages of the European Union. Two or three languages are printed at the relevant points, followed by reference numbers which point to the passport page where translations into the remaining languages appear.

- Canadian passports are written in both English and French, though French is included in this case due to its position as an official language of Canada.

- The Barbadian passport and the United States passport are tri-lingual: English, French and Spanish. United States passports were traditionally English and French, but began being printed with a Spanish message and labels during the late 1990s, in recognition of Puerto Rico's Spanish-speaking status. Only the message and labels are in multiple languages, the cover and instructions pages are printed solely in English.

- In Belgium, all three official languages (Dutch, French, German) appear on the cover, in addition to English on the main page. The order of the official languages depends on the official residence of the holder.

- Passports of Bosnia and Herzegovina are in the three official languages of Bosnian, Serbian and Croatian in addition to English.

- Brazilian passports contain four languages: Portuguese, the official country language, Spanish, because of bordering nations, English and French.

- British passports bear English and French on the information page and Welsh and Scottish Gaelic translations on an extra page.

- Cypriot passports are in Greek, Turkish and English.

- The first page of a Libyan passport is in Arabic only. The last page (first page from a western viewpoint) has an English equivalent of the information on the Arabic first page (western last page). Similar arrangements are found in the passports of some other Arab countries.

- Indian passports are in English and Hindi.

- Iraqi passports are in Arabic, Kurdish and English.

- Macau SAR passports are in three languages: Chinese, Portuguese and English.

- New Zealand passports are in English and Māori.

- Norwegian passports are in the two forms of the Norwegian language, Bokmål and Nynorsk, and in English.

- Pakistani passports are issued in English and Urdu.

- Sri Lankan passports are in Sinhala, Tamil and English.

- Swiss passports are in five languages: German, French, Italian, Romansh and English.

- Lebanese Passports are in three languages: Arabic, English, and French.

- Syrian passports are in Arabic, English, and French.

- Nepalese passports are in English, and Nepalese.

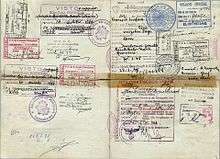

Immigration stamps

For immigration control, officials of many countries use entry and exit stamps. Depending on the country, a stamp can serve different purposes. For example, in the United Kingdom, an immigration stamp in a passport includes the formal leave to enter granted to a person subject to entry control. In other countries, a stamp activates or acknowledges the continuing leave conferred in the passport bearer's entry clearance.

Under the Schengen system, a foreign passport is stamped with a date stamp which does not indicate any duration of stay. This means that the person is deemed to have permission to remain either for three months or for the period shown on his visa if specified otherwise.

Visas often take the form of an inked stamp, although some countries use adhesive stickers that incorporate security features to discourage forgery.

Member states of the European Union are not permitted to place a stamp in the passport of a person who is not subject to immigration control. Stamping is prohibited because it is an imposition of a control that the person is not subject to.

Countries usually have different styles of stamps for entries and exits, to make it easier to identify the movements of people. Ink colour might be used to designate mode of transportation (air, land or sea), such as in Hong Kong prior to 1997; while border styles did the same thing in Macau. Other variations include changing the size of the stamp to indicate length of stay, as in Singapore.

Immigration stamps are a useful reminder of travels. Some travellers "collect" immigration stamps in passports, and will choose to enter or exit countries via different means (for example, land, sea or air) in order to have different stamps in their passports. Some countries, such as Liechtenstein,[62] that do not stamp passports may provide a passport stamp on request for such "memory" purposes. Monaco (at its tourist office) and Andorra (at its border) do this as well. These are official stamps issued by government offices. However, some private enterprises may for a price stamp passports at historic sites and these have no legal standing. It is possible that such memorial stamps can preclude the passport bearer from travelling to certain countries. For example, Finland consistently rejects what they call 'falsified passports', where passport bearers have been refused visas or entry due to memorial stamps and are required to renew their passports.

Limitations on use

A passport is merely an identity document that is widely recognised for international travel purposes, and the possession of a passport does not in itself entitle a traveller to enter any country other than the country that issued it, and sometimes not even then. Many countries normally require visitors to obtain a visa. Each country has different requirements or conditions for the grant of visas, such as for the visitor not being likely to become a public charge for financial, health, family, or other reasons, and the holder not having been convicted of a crime or considered likely to commit one.[3][63]

Where a country does not recognise another, or is in dispute with it, entry may be prohibited to holders of passports of the other party to the dispute, and sometimes to others who have, for example, visited the other country; examples are listed below. A country that issues a passport may also restrict its validity or use in specified circumstances, such as use for travel to certain countries for political, security, or health reasons.

Asia

- Bangladesh – a Bangladeshi passport is valid for travel to all countries except Israel.

- Mainland China and Taiwan – Nationals of Taiwan (ROC) use a special travel permit (Mainland Travel Permit for Taiwan Residents) issued by China's (PRC) Ministry of Public Security to enter mainland China. Nationals of Mainland China entering Taiwan must also use a special travel permit (Exit & Entry Permit) issued by the ROC's immigration department. Depending on where they're coming from, they also need either a Chinese passport when departing from outside Mainland China, or a passport-like travel document, known as Taiwan Travel Permit for Mainland Residents, when departing from Mainland China (along with a special visa-like exit endorsement issued by PRC immigration authorities affixed to the permit). Chinese nationals who are Hong Kong and Macau permanent residents can apply for the ROC Exit and Entry Permit online or on arrival and must travel with their HKSAR passport, MSAR passport, or BN(O) passport.

- Hong Kong and Macau – A 'Home Return Permit' is required for Chinese citizens domiciled in Hong Kong and Macau to enter and exit mainland China. The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region passport and the Macau Special Administrative Region passport cannot be used for travel to mainland China. Also, British National (Overseas) passports cannot be used by Chinese citizens who reside in Hong Kong as the PRC does not recognize dual nationality. Mainland China residents visiting Hong Kong or Macau are required to hold an Exit-entry Permit for Travelling to and from Hong Kong and Macau (往来港澳通行证 or 双程证) issued by Mainland authorities, along with an endorsement (签注), on the Exit-entry Permit which needs to be applied each time (similar to a visa) when visiting the SARs (except residents with hukou in Shenzhen can apply for a multi-entry endorsement).[64] Non-permanent residents of Macau who are not eligible for a passport may travel to Hong Kong on the Visit Permit to Hong Kong (澳門居民往來香港特別行政區旅行證) valid for 7 years, which allows holders to travel only to Hong Kong SAR during its validity.

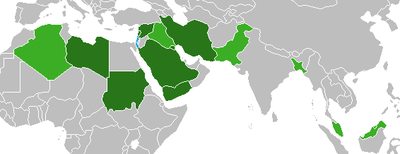

- Israel – Until 1952, Israeli passports were normally not valid for travel to the then-West Germany, as in the aftermath of the Holocaust it was considered improper for Israelis to visit West Germany on any business but official state affairs. Some Muslim and African countries do not permit entry to anyone using an Israeli passport. In addition, Iran,[65] Kuwait,[66] Lebanon,[67] Libya,[68] Saudi Arabia,[69] Sudan,[70] Syria[71] and Yemen[72] do not allow entry to people with evidence of travel to Israel, or whose passports have either a used or an unused Israeli visa. For this reason, Israel no longer stamps visa stamps directly on passports, but on a slip of paper that serves as a substitute for a stamp on a travel document. Some countries do not permit their passports to be used for travel to Israel.

Legend:IsraelCountries that reject passports from IsraelCountries that reject passports from Israel and any other passports which contain Israeli stamps or visas

Legend:IsraelCountries that reject passports from IsraelCountries that reject passports from Israel and any other passports which contain Israeli stamps or visas - Lebanon – a Lebanese Passport is valid to travel to all countries except Israel.

- Malaysia – a Malaysian passport is valid to travel to all countries except Israel.

- Brunei – a Bruneian passport is valid to travel to all countries except Israel.

- Pakistan – a Pakistani passport is valid for travel to all countries except Israel.

- Philippines – between 2004 and mid-2011, Philippine passports could not be used for travel to Iraq due to the security threats in that country.[73]

- South Korea – the South Korean government has banned travel to Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen for safety reasons.[74] South Korea does not consider travel within the Korean peninsula (between South Korean and North Korean administrations) to be international travel, as South Korea's constitution regards the entire Korean peninsula as its territory. South Koreans going to the Kaesong Industrial Region in North Korea pass through the Gyeongui Highway Transit Office at Dorasan, Munsan, where they present a plastic Visit Certificate (방문증명서) card issued by the South Korean Ministry of Unification, and an immigration-stamped Passage Certificate (개성공업지구 출입증) issued by the Kaesong Industrial District Management Committee (개성공업지구 관리위원회).[75] Until 2008, South Koreans moving to tourist areas in the North such as Mount Kumgang needed to carry a South Korean ID card for security reasons.

Europe

- As a result of the Nagorno-Karabakh War between Azerbaijan and Armenia, Azerbaijan refuses entry to holders of Armenian passports, as well as passport-holders of any other country if they are of Armenian descent. It also strictly refuses entry to foreigners in general whose passport shows evidence of entry into the self-proclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, immediately declaring them permanent personae non gratae. Conversely, Armenia does allow visa-free entry for holders of Azerbaijani passports.

- The Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) issues passports, but only Turkey recognises its statehood. TRNC passports are not accepted for entry into the Republic of Cyprus via airports or sea ports, but are accepted at the designated green line crossing points. However, all Turkish Cypriots are entitled by law to the issue of a Republic of Cyprus EU passport, and since the opening of the border between the two sides, Cypriot and EU citizens can travel freely between them. The United Kingdom, United States, France, Australia, Pakistan, and Syria currently officially accept TRNC passports with the relevant visas.

- Spain does not accept United Kingdom passports issued in Gibraltar, alleging that the Government of Gibraltar is not a competent authority for issuing UK passports. The word "Gibraltar" now appears beneath the words "United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland" on the covers of British passports issued in Gibraltar.

- British passports may be issued to people holding any of the various forms of British nationality, with holders identified as of 2014 as: British citizens (GBR), British Overseas Territories Citizens (GBD), British Overseas citizens (GBO), British subjects (GBS), British protected persons (GBP), and British Nationals (Overseas) (GBN or BN(O)). Holders other than British citizens may not have the right to enter or reside in the United Kingdom, and other countries may apply restrictions that do not apply to GBR holders.

Oceania

- Some countries do not accept Tongan Protected Person passports, though they accept Tongan citizen passports.[76] Tongan Protected Person passports are sold by the Government of Tonga to anyone who is not a Tongan national.[77] A holder of a Tongan Protected Person passport is forbidden to enter or settle in Tonga. Generally, those holders are refugees or stateless persons for some other reason.

South America

- For countries that do not maintain diplomatic relations with Brazil, such as Kosovo, Taiwan, and Western Sahara, diplomatic, official, and work passports are not accepted, and visas are only granted to tourist or business visitors. In addition, except for Kosovo and Taiwan, these visas must be issued on a Brazilian "laissez-passer", not on the country's passport.[78]

International travel without passports

International travel is possible without passports in some circumstances.[79] Nonetheless, a document stating citizenship, such as a national identity card or an Enhanced Drivers License, is usually required.[79]

Africa

- Members of the East African Community (composed of Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi) may issue an East African passport. East African passports are recognised by only the five members, and are only used for travel between or among those countries. The requirements for eligibility are less rigorous than are the requirements for national passports used for other international travel.

- The member states of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) do not require passports for their citizens when moving within the community. National ID cards are sufficient. The member states are Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo.

Asia

- Passports are not needed by citizens of India and Nepal to travel to each other's country, but some identification is required for border crossings.

- Citizens of Lebanon and Jordan do not require passports when travelling in either country if they are carrying ID cards.

- Travel between Russia and some former Soviet republics, designated by membership in the Commonwealth of Independent States, may be accomplished with a national identity document (e.g. an internal passport) or passport. However, according to a statement made by President Putin in December 2012, Russia has plans to restrict travel without a passport only to citizens of the member states of the Customs Union of Belarus, Kazakhstan and Russia by 2015. After that date, citizens of other CIS states will need passports (although not visas) to visit Russia.[80]

- Citizens of the Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf countries need only national ID cards (also referred to as civil ID cards) to cross the borders of council countries. This also applies to anyone that has a residence permit in any of the GCC countries. As of 2017 though, Qatar has been removed from the list.

- The 20 countries of the APEC issue the APEC Business Travel Card, which allows visa-free entry into all participating countries.

Europe

- Travel with minimal travel documents is possible between the United Kingdom, the Isle of Man, the Channel Islands, and the Republic of Ireland, which together form the Common Travel Area.

- The countries that apply the Schengen Agreement (Schengen Area, a subset of the EEA) do not implement passport controls between each other, unless exceptional circumstances occur. It is, however, mandatory to carry a passport, compliant national identity card, alien's resident permit or some other photo ID.

- A citizen of one of the 27 member states of the European Union or of Liechtenstein, Andorra, Monaco, Norway, San Marino, Iceland and Switzerland may travel in and between these countries using a standard compliant National Identity Card rather than a passport. Not all EU/EEA member states issue standard compliant national identity cards, notably Denmark, Norway, Iceland, the Republic of Ireland (though the Irish passport card is accepted), and the United Kingdom.

- The Nordic Passport Union allows Nordic citizens—citizens from Denmark (including the Faroe Islands), Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden to visit any of these countries without being in possession of identity documents (Greenland and Svalbard are excluded). This is an extension of the principle that Nordic citizens need no identity document in their own country. A means to prove identity when requested is recommended (e.g. using a driver's license, which does not state citizenship), even in one's own country. Joining the Schengen Area in 1997 has not changed these rules.

- Albania accepts national ID cards or passports for entry from nationals of the EU, EFTA, Bosnia & Herzegovina, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Monaco, Montenegro, North Macedonia, San Marino and Singapore.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina accepts national ID cards or passports for entry from citizens of the EU, EFTA, Montenegro, Monaco, San Marino and Serbia.

- North Macedonia accepts national ID cards or passports for entry from nationals of the EU, EFTA, Albania, Montenegro,Bosnia & Hercegovina, Kosovo and Serbia.

- Montenegro accepts national ID cards or passports for entry from nationals of the EU, EFTA, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Monaco, North Macedonia, San Marino and Serbia.

- Serbia accepts national ID cards or passports for entry from nationals of the EU, EFTA (except Liechtenstein), Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and North Macedonia.

- Citizens of Belgium, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Italy, Liechtenstein, Luxemburg, Malta, the Netherlands, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and Ukraine are allowed to enter Turkey with a valid national ID card.

- EU and Turkish citizens are allowed to enter the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus with a valid ID card.

- EU and Turkish citizens are allowed to enter Georgia with a valid ID card.

North America

- CARICOM countries issue a CARICOM passport to their citizens, and as of June 2009, eligible nationals in participating countries will be permitted to use the CARICOM travel card which provides for intra-community travel without a passport.

- There are several cards available to certain North American residents which allow passport free travel; generally only for land and sea border crossings:

- The U.S. Passport card is an alternative to an ordinary U.S. passport booklet for land and sea travel within North America (Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, and Bermuda). Like the passport book, the passport card is issued only to U.S. citizens and non-citizen nationals.[81]

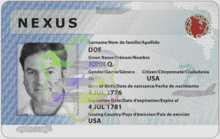

- The NEXUS card allows border crossing between the U.S. and Canada for U.S. nationals and Canadian citizens. It can also be used for air travel as the only means of identification for U.S. nationals and Canadian citizens. The card can also be used for entering the U.S. from Mexico but not vice versa.[81]

- The SENTRI card allows passport-free entry into the U.S. from Mexico and Canada (but not vice versa) for U.S. citizens and nationals as well as Canadian citizens.[81]

- The FAST card can be used for crossing between U.S. and Canada, as well as entering U.S. from Mexico for U.S. and Canadian citizens.[81]

- U.S. nationals may further enter the U.S. and Canada using an enhanced driver license issued by the States of Vermont, Washington, Michigan and New York (which qualify as WHTI compliant). Other documents that can be used to enter the U.S. include: enhanced tribal cards; U.S. military ID cards plus military travel orders; U.S. merchant mariner ID cards, when travelling on maritime business; Native American tribal ID cards; Form I-872 American Indian card.[81]

- Canadian citizens may enter the U.S. and Canada via land or sea using an enhanced WHTI-compliant driver's license. These are currently issued by British Columbia, Manitoba, and Ontario. If Canadians wish to enter the U.S. via air, they must use a passport book or a NEXUS card.[81]

- Canadian citizens may return to Canada using any proof of citizenship and identity, however those without an acceptable document will be questioned by a Border Services officer until their identity is established.[82]

- For travel to the French islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon directly from Canada, Canadians and foreign nationals holding Canadian identification documents are exempted from passport and visa requirements for stays of maximum duration of 3 months within a period of 6 months. Accepted documents include a driver's licence, citizenship card, permanent resident card and others. Those without Canadian identifications are not exempt and must carry a passport.

Oceania

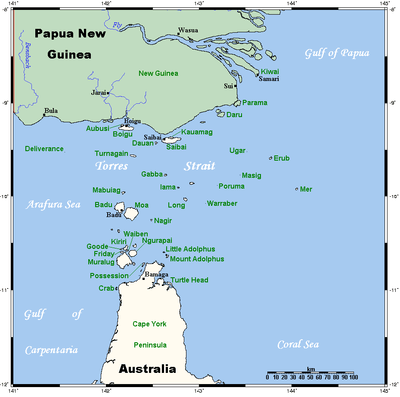

- Residents of nine coastal villages in Papua New Guinea are permitted to enter the 'Protected Zone' of the Torres Strait (part of Queensland, Australia) for traditional purposes. This exemption from passport control is part of a treaty between Australia and Papua New Guinea negotiated when PNG became independent from Australia in 1975.[83] Vessels from other parts of Papua New Guinea and other countries attempting to cross into Australia or Australian waters are stopped by Australian Customs or the Royal Australian Navy.

South America

- Many Central American and South American nationals can travel within their respective regional economic zones, such as Mercosur and the Andean Community of Nations, or on a bilateral basis (e.g., between Chile and Peru, between Brazil and Chile), without passports, presenting instead their national ID cards, or, for short stays, their voter-registration cards. In some cases this travel must be done overland rather than by air.

Mercosur citizens can travel visa-free and only with their ID cards between the member and associated countries (Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay, Brazil and Argentina). [84]

See also

Notes

- All nations issuing EU passports make an effort to ensure that their passports feature nationally distinctive designs. Finnish passports make a flip-book of a moose walking. The UK passport launched on 3 November 2015 features Shakespeare's Globe Theater on pages 26–27, with architectural plans as well as performers on stage. Each UK passport page is completely different from all the other pages and from all the other pages of other EU passports.

References

- Cane, P & Conaghan, J (2008). The New Oxford Companion to Law. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199290543.

- The electronic passport in 2018 and beyond

- "ilink – USCIS". uscis.gov.

- Boesche, Roger (2003). The First Great Political Realist: Kautilya and His Arthashastra. Lexington Books. pp. 62 A superintendent must issue sealed passes before one could enter or leave the countryside(A.2.34.2, 181) a practice that might constitute the first passbooks and passports in world history. ISBN 9780739106075.

- China's early empires : a re-appraisal. Nylan, Michael., Loewe, Michael. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2010. pp. 297, 317–318. ISBN 9780521852975. OCLC 428776512.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Frank, Daniel (1995). The Jews of Medieval Islam: Community, Society, and Identity. Brill Publishers. p. 6. ISBN 90-04-10404-6.

- George William Lemon (1783). English etymology; or, A derivative dictionary of the English language. p. 397. said that passport may signify either a permission to pass through a portus or gate, but noted that an earlier work had contained information that a traveling warrant, a permission or license to pass through the whole dominions of any prince, was originally called a pass par teut.

- James Donald (1867). Chamber's etymological dictionary of the English language. W. and R. Chambers. pp. 366.

passport, pass'pōrt, n. orig. permission to pass out of port or through the gates; a written warrant granting permission to travel.

- Lopez, Robert Sebationo; W. Raymond, Irving (2001). Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World: Illustrative Documents. Columbia University Press. pp. 36–39.

- A brief history of the passport - The Guardian

- Casciani, Dominic (2008-09-25). "Analysis: The first ID cards". BBC. Retrieved 2008-09-27.

- John Torpey, Le contrôle des passeports et la liberté de circulation. Le cas de l'Allemagne au XIXe siècle, Genèses, 1998, n° 1, pp. 53–76

- "History of Passports". Government of Canada. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- Marrus, Michael, The Unwanted: European Refugees in the Twentieth Century. New York: Oxford University Press (1985), p. 92.

- "League of Nations Photo Archive – Timeline – 1920". Indiana University. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- "League of Nations 'International' or 'Standard' passport design". IU. Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2010-06-27. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "International Conferences – League of Nations Archives". Center for the Study of Global Change. 2002. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- "Welcome to the ICAO Machine Readable Travel Documents Programme". ICAO. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- Machine Readable Travel Documents, Doc 9303 (Sixth ed.). ICAO. 2006. Retrieved 2013-08-09.

- Arkelian, A.J. "The Right to a Passport in Canadian Law." The Canadian Yearbook of International Law, Volume XXI, 1983. Republished in November 2012 in Artsforum Magazine at http://artsforum.ca/ideas/in-depth

- Arkelian, A.J. "Freedom of Movement of Persons Between States and Entitlement to Passports". Saskatchewan Law Review, Volume 49, No. 1, 1984–85.

- "What Is a Passport Seizure?".

- Devine, F. E (1991). Commercial bail bonding: a comparison of common law alternatives. ABC-CLIO. pp. 84, 91, 116, 178. ISBN 978-0-275-93732-4.

- Hannum, Hurst (1987). The Right to Leave and Return in International Law and Practice. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 73. ISBN 9789024734450. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- "Government of Pakistan, Directorate General of Immigration & Passports". Dgip.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 2009-08-06. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- Hanif, Mohammed (16 June 2010). "Why Pakistan's Ahmadi community is officially detested". BBC News.

- "Passports for persons liable for military service". Finnish Police. 2009. Archived from the original on 2008-10-14. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- "Passports for Syrian Citizens". Archived from the original on 2012-11-13. Retrieved 2013-01-11.

- Crocombe, R. G. (2007). Asia in the Pacific Islands: replacing the West. University of South Pacific Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-982-02-0388-4.

- "Question 1". Dear Uncle Ezra... Cornell University. 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- Wallace, William N. (1990-06-12). "Putting Tradition to the Test". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-21.

- "The New e-Passport". Osterreichs Bundesheer (in German and English). Eigentümer und Herausgeber: Bundesministerium für Landesverteidigung und Sport. February 2006. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". US Department of State. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- "The Henley Passport Index" (PDF). Henley & Partners. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "Guidance ECB08: What are acceptable travel documents for entry clearance". Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- "Collective (group) passports". GOV.UK. Government Digital Service. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- "Passports for children". Canada.CA. Government of Canada. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Population of Latvia by ethnicity and nationality; Office of Citizenship and Migration Affairs 2015(in Latvian)

- Section 1 and Section 8, Law "On the Status of those Former U.S.S.R. Citizens who do not have the Citizenship of Latvia or that of any Other State" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Amnesty International 2009 Report Archived 2009-06-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Hammarberg, Thomas. "No one should have to be stateless in today's Europe". Council of Europe: Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- In the Panama Canal Zone only those persons born there prior to January 1, 2000 with at least one parent as a U.S. citizen were recognized as U.S. citizens and were both nationals and citizens. Also in the former Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands the residents were considered nationals and citizens of the Trust Territory and not U.S. nationals.

- "8 FAM 505.2 Passport Endorsements". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2018-07-18. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - British passport eligibility

- "National Web Portal Of Bangladesh – Citizen Services". Bangladesh.gov.bd. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- "Visas for Diplomats and Foreign Government Officials". travel.state.gov. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- Document In Lieu of Internal Travel Document IMM.114, Immigration Department of Malaysia; retrieved 26 March 2014

- "NorfolkIsland.com". Archived from the original on 2016-02-04. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- "Doc 9303: Machine Readable Travel Documents" (PDF). Seventh Edition, 2015. 999 Robert-Bourassa Boulevard, Montréal, Quebec, Canada H3C 5H7: International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

ICAO's work on machine readable travel documents began in 1968 with the establishment, by the Air Transport Committee of the Council, of a Panel on Passport Cards. This Panel was charged with developing recommendations for a standardized passport book or card that would be machine readable, in the interest of accelerating the clearance of passengers through passport controls. ... In 1998, the New Technologies Working Group of the TAG/MRTD began work to establish the most effective biometric identification system and associated means of data storage for use in MRTD applications, particularly in relation to document issuance and immigration considerations. The bulk of the work had been completed by the time the events of 11 September 2001 caused States to attach greater importance to the security of a travel document and the identification of its holder. The work was quickly finalized and endorsed by the TAG/MRTD and the Air Transport Committee. ... The Seventh Edition of Doc 9303 represents a restructuring of the ICAO specifications for Machine Readable Travel Documents. Without incorporating substantial modifications to the specifications, in this new edition Doc 9303 has been reformatted into a set of specifications for Size 1 Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (TD1), Size 2 Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (TD2), and Size 3 Machine Readable Travel Documents (TD3) ...

CS1 maint: location (link) - Doc 9303: Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 2: Specifications for the Security of the Design, Manufacture and Issuance of MRTDs (PDF). Seventh Edition, 2015. 999 Robert-Bourassa Boulevard, Montréal, Quebec, Canada H3C 5H7: International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). 2015. ISBN 978-92-9249-791-0. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

The Seventh Edition of Doc 9303 represents a restructuring of the ICAO specifications for Machine Readable Travel Documents. Without incorporating substantial modifications to the specifications, in this new edition Doc 9303 has been reformatted into a set of specifications for Size 1 Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (TD1), Size 2 Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (TD2), and Size 3 Machine Readable Travel Documents (TD3), as well as visas. This set of specifications consists of various separate documents in which general (applicable to all MRTDs) as well as MRTD form factor specific specifications are grouped ... Where the substrate used for the biographical data page (or inserted label) of a passport book or MRTD card is formed entirely of plastic or a variation of plastic, it is not usually possible to incorporate many of the security components described in 5.1.1 through 5.1.3 ... A.5.2.5 Special security measures for use with cards and biographical data pages made of plastic Where a travel document is constructed entirely of plastic, optically variable security features shall be employed which give a changing appearance with angle of viewing. Such devices may take the form of latent images, lenticular features, colour-shifting ink, or diffractive optically variable image features.

CS1 maint: location (link) - Doc 9303: Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 3: Specifications Common to all MRTDs (PDF). Seventh Edition, 2015. 999 Robert-Bourassa Boulevard, Montréal, Quebec, Canada H3C 5H7: International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). 2015. ISBN 978-92-9249-792-7. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

Part 3 defines specifications that are common to TD1, TD2 and TD3 size machine readable travel documents (MRTDs) including those necessary for global interoperability using visual inspection and machine readable (optical character recognition) means. Detailed specifications applicable to each form factor appear in Doc 9303, Parts 4 through 7.

CS1 maint: location (link) - Doc 9303: Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 5: Specifications for TD1 Size Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (MROTDs) (PDF). Seventh Edition, 2015. 999 Robert-Bourassa Boulevard, Montréal, Quebec, Canada H3C 5H7: International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO). 2015. ISBN 978-92-9249-794-1. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

The nominal dimensions shall be those specified in ISO/IEC 7810 for the ID-1 type card: 53.98 mm x 85.6 mm (2.13 in x 3.37 in) ... The edges of the document after final preparation shall be within the area circumscribed by the concentric rectangles as illustrated in Figure 1. Inner rectangle: 53.25 mm x 84.85 mm (2.10 in x 3.34 in), Outer rectangle: 54.75 mm x 86.35 mm (2.16 in x 3.40 in). In no event shall the dimensions of the finished TD1 document exceed the dimensions of the outer rectangle, including any final preparation (e.g. laminate edges) ... Note k: The first character shall be A, C or I. Historically these three characters were chosen for their ease of recognition in the OCR-B character set. The second character shall be at the discretion of the issuing State or organization except that V shall not be used, and C shall not be used after A except in the Crew Member Certificate.

CS1 maint: location (link) - "U.S. Passport Service Guide – Passport Card Facts". 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2015.

A passport card serves the same purpose as a passport book. It attests to your United States citizenship and your identity. The passport card is a fully valid passport. However, it is similar in size to a credit card ... Production of the passport card began on July 14, 2008. Millions of cards have already been issued since that date.

- "How Your Passport is Made – Exclusive Behind-The-Scenes Footage". National Archives. July 1, 2013. Archived from the original on January 14, 2014.

- "Machine Readable Travel Documents (MRTD)" (PDF). ICAO. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- "The ID Chip You Don't Want in Your Passport". Bruce Schneier. 2006-09-16. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- "Scan This Guy's E-Passport and Watch Your System Crash". Kim Zetter. 1 August 2007. Archived from the original on August 1, 2007. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- Resolutions of 23 June 1981, 30 June 1982, 14 July 1986 and 10 July 1995 concerning the introduction of a passport of uniform pattern, OJEC, 19 September 1981, C 241, p. 1; 16 July 1982, C 179, p. 1; 14 July 1986, C 185, p. 1; 4 August 1995, C 200, p. 1.

- "Council Regulation (EC) No 2252/2004 of 13 December 2004 on standards for security features and biometrics in passports and travel documents issued by Member States". Official Journal of the European Union. 29 December 2004. Retrieved 6 October 2010. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Andean Community / Decision 525: Minimum specific technical characteristics of Andean Passport.

- Baenninger, Martin (2009). In the eye of the wind: a travel memoir of prewar Japan. Footprints. Footprints. Cheltenham, England: McGill-Queen's Press – MQUP. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7735-3497-1. Retrieved 2011-11-17.

- "About Liechtenstein - Tourism Overview". about-liechtenstein.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-06-20. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- Chris Brown won't be able to come to Australia unless he challenges visa refusal and wins

- "Arrangement for entry to Hong Kong from Mainland China". Immigration Department, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. www.immd.gov.hk. Archived from the original on 2008-06-01. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- "Travel Advice for Iran – Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade". Smartraveller.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- "Travel Report – Kuwait". Voyage.gc.ca. 2012-11-16. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- Travel Advice for Lebanon – Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Archived 2008-12-24 at the Wayback Machine and Lebanese Ministry of Tourism Archived 2009-03-27 at the Wayback Machine

- "Travel Advice for Libya – Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade". Smartraveller.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2013-06-22. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- Michael Freund, Canada defends Saudi policy of shunning tourists who visited Israel, 7 December 2008, Jerusalem Post

- "Travel Advice for Sudan – Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade". Smartraveller.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2013-07-05. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- Travel Advice for Syria - Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Archived 2008-12-19 at the Wayback Machine and Syrian Ministry of Tourism

- "Travel Advice for Yemen – Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade". Smartraveller.gov.au. Archived from the original on 2011-08-20. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- "Passport General Information". Newyorkpcg.org. Archived from the original on 2013-06-30. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- S. Korea extends travel ban on four nations, Yonhap News, July 23, 2013

- "한국일보 : 北초청장 없어도 개성공단 방문가능". News.hankooki.com. 2007-03-25. Archived from the original on 2013-07-27. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- "GEN 1.3 ENTRY, TRANSIT AND DEPARTURE OF PASSENGERS AND CREW" (PDF). Retrieved 2015-09-26.

- Paul TherouxPublished: June 07, 1992 (1992-06-07). "In the Court of the King of Tonga". New York Times. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- Entrance Visas in Brazil Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine, Ministry of Foreign Relations of Brazil, August 12, 2015.

- PASSPORT & VISA REQUIREMENTS Archived 2017-08-03 at the Wayback Machine (Timatic, through olympicair.com)

- Путин: въезд в РФ должен быть разрешен только по загранпаспортам (Putin: passports will be required for entering Russia), 2012-12-12 (in Russian)

- Western Hemisphere Travel Initiative

- Travel Documents

- "Torres Strait Treaty and You - What is free movement for traditional activities?". Australian Government = Dept. of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 3 March 2010.

- https://www.mercosur.int/documento/acuerdo-documentos-de-viaje/

Further reading

- Advisory and technical committee for communications and transit. Replies of the governments to the enquiry on the application of the resolutions relating to passports, customs formalities and through tickets. Geneva: League of Nations. 1922. OCLC 46235968.

- Holder IV, Floyd William (Fall 2009). An Empirical Analysis of the State's Monopolization of the Legitimate Means of Movement: Evaluating the Effects of Required Passport use on International Travel (M. P. A. thesis). San Marcos: Texas State University. OCLC 503473693. Docket Applied Research Projects, Paper 308.

- Lloyd, Martin (2008) [2003]. The Passport: The History of Man's Most Travelled Document (2nd ed.). Canterbury: Queen Anne's Fan. ISBN 978-0-9547150-3-8. OCLC 220013999.

- Salter, Mark B. (2003). Rights of Passage: The Passport in International Relations. Boulder, Co: Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58826-145-8. OCLC 51518371.

- Torpey, John C. (2000). The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State. Cambridge studies in law and society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-63249-8. OCLC 59408523.

- United States; Hunt, Gaillard (1898). The American Passport; Its History and a Digest of Laws, Rulings and Regulations Governing Its Issuance by the Department of State. Washington: Govt. print. off. OCLC 3836079.

External links

| Wikivoyage has an article for Passports. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Passport. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Passports. |

- PRADO – The Council of the European Union Public Register of Authentic Travel- and ID Documents Online

- How Passports Work US-focused information from Howstuffworks

- Investigation into passport fraud, Dateline NBC, December 28, 2007

- Passport-free travel to begin for citizens of nine more European countries, Seattle Times, November 8, 2007