Swiss mercenaries

Swiss mercenaries (Reisläufer) were notable for their service in foreign armies, especially the armies of the Kings of France, throughout the Early Modern period of European history, from the Later Middle Ages into the Age of Enlightenment. Their service as mercenaries was at its peak during the Renaissance, when their proven battlefield capabilities made them sought-after mercenary troops. There followed a period of decline, as technological and organizational advances counteracted the Swiss' advantages. Switzerland's military isolationism largely put an end to organized mercenary activity; the principal remnant of the practice is the Pontifical Swiss Guard at the Vatican.

In William Shakespeare's Hamlet, Act IV, Scene 5, Swiss mercenaries are called "Switzers" (Switzer is actually what the Swiss were called in English until the 19th century, hence Switzerland).

Ascendancy

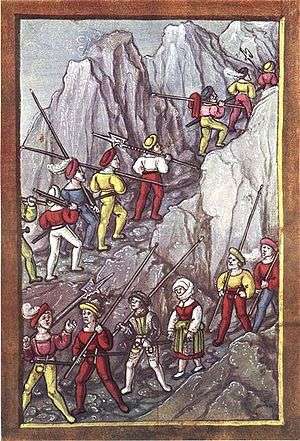

During the Late Middle Ages, mercenary forces grew in importance in Europe, as veterans from the Hundred Years War and other conflicts came to see soldiering as a profession rather than a temporary activity, and commanders sought long-term professionals rather than temporary feudal levies to fight their wars. Swiss mercenaries (Reisläufer) were valued throughout Late Medieval Europe for the power of their determined mass attack in deep columns with the spear, the pike and halberd. Hiring them was made even more attractive because entire ready-made Swiss mercenary contingents could be obtained by simply contracting with their local governments, the various Swiss cantons—the cantons had a form of militia system in which the soldiers were bound to serve and were trained and equipped to do so. Some Swiss also hired themselves out individually or in small bands.

The warriors of the Swiss cantons had gradually developed a reputation throughout Europe as skilled soldiers, due to their successful defense of their liberties against their Austrian Habsburg overlords, starting as early as the late thirteenth century, including remarkable upset victories over heavily armoured knights at Morgarten and Laupen. This was furthered by later successful campaigns of regional expansion (mainly into Italy). By the fifteenth century they were greatly valued as mercenary soldiers, particularly following their series of notable victories in the Burgundian Wars in the latter part of the century. The standing mercenary army of king Matthias Corvinus of Hungary (Black Army of Hungary 1458–1490) also contained Swiss pikemen units, who were held in high honour by the king.[1] The native term Reisläufer literally means "one who goes to war" and is derived from Middle High German Reise, meaning "military campaign".

The Swiss, with their head-down attack in huge columns with the long pike, refusal to take prisoners, and consistent record of victory, were greatly feared and admired—for instance, Machiavelli addresses their system of combat at length in chapter 12 of The Prince. The Valois Kings of France, in fact, considered it a virtual impossibility to take the field of battle without Swiss pikemen as the infantry core of their armies. (Although often referred to as "pikemen", the Swiss mercenary units also contained halberdiers as well until several decades into the sixteenth century, as well as a small number of skirmishers armed with bows and crossbows or crude firearms to precede the rapid advance of the attack column.)

The young men who went off to fight, and sometimes die, in foreign service had several incentives—limited economic options in the still largely rural cantons; adventure; pride in the reputation of the Swiss as soldiers; and finally what military historian Sir Charles Oman describes as a pure love of combat and warfighting in and of itself, forged by two centuries of conflict.

Landsknechts and the Italian Wars

Until roughly 1490, the Swiss had a virtual monopoly on pike-armed mercenary service. However, after that date, the Swiss mercenaries were increasingly supplanted by imitators, chiefly the Landsknechts. Landsknechts were Germans (at first largely from Swabia) and became proficient at Swiss tactics, even surpassing them with their usage of the Zweihänder to crush opposing pike formations. This produced a force that filled the ranks of European armies with mercenary regiments for decades. After 1515 the Swiss pledged themselves to neutrality, other than regarding Swiss soldiers serving in the ranks of the Royal French army. The Landsknecht, however, would continue to serve any paymaster, even, at times, enemies of the Holy Roman Emperor (and Landsknechts at times even fought each other on the battlefield). The Landsknecht often assumed the multi-coloured and striped clothing of the Swiss.

The Swiss were not flattered by the imitation, and the two bodies of mercenaries immediately became bitter rivals over employment and on the battlefield, where they were often opposed during the major European conflict of the early sixteenth century, the Great Italian Wars. Although the Swiss generally had a significant edge in a simple "push of pike", the resulting combat was nonetheless quite savage, and known to Italian onlookers as "bad war". Period artists such as Hans Holbein attest to the fact that two such huge pike columns crashing into each other could result in a maelstrom of battle, with very many dead and wounded on both sides.

Despite the competition from the Landsknechts, and imitation by other armies (most notably the Spanish, which adopted pike-handling as one element of its tercios), the Swiss fighting reputation reached its zenith between 1480 and 1525, and indeed the Battle of Novara, fought by Swiss mercenaries, is seen by some as the perfect Swiss battle. Even the close defeat at the terrible Battle of Marignano in 1515, the "Battle of Giants", was seen as an achievement of sorts for Swiss arms due to the ferocity of the fighting and the good order of their withdrawal.

Nonetheless, the repulse at Marignano presaged the decline of the Swiss form of pike warfare—eventually, the two-century run of Swiss victories ended in 1522 with disaster at the Battle of Bicocca when combined Spanish tercios and Landsknecht forces decisively defeated them using superior tactics, fortifications, artillery, and new technology (i.e. handguns). At Bicocca, the Swiss mercenaries, serving the French king, attempted repeatedly to storm an impregnable defensive position without artillery or missile support, only to be mown down by small-arms and artillery fire. Never before had the Swiss suffered such heavy losses while being unable to inflict much damage upon their foe.

Organization and tactics

The early contingents of Swiss mercenary pikemen organized themselves rather differently than the cantonal forces. In the cantonal forces, their armies were usually divided into the Vorhut (vanguard), Gewalthut (center) and Nachhut (rearguard), generally of different sizes. In mercenary contingents, although they could conceivably draw up in three similar columns if their force was of sufficient size, more often they simply drew up in one or two huge columns which deployed side by side, forming the center of the army in which they served. Likewise, their tactics were not very similar to those used by the Swiss cantons in their brilliant tactical victories of the Burgundian Wars and Swabian War, in which they relied on maneuver at least as much as the brute force of the attack columns. In mercenary service they became much less likely to resort to outmaneuvering the enemy and relied more on a straightforward steamroller assault.

Such deep pike columns could crush lesser infantry in close combat and were invulnerable to the effects of a cavalry charge, but they were vulnerable to firearms if they could be immobilized (as seen in the Battle of Marignano). The Swiss mercenaries did deploy bows, crossbows, handguns and artillery of their own, however these always remained very subsidiary to the pike and halberd square. Despite the proven armour-penetration capability of firearms, they were also very inaccurate, slow-loading, and susceptible to damp conditions, and did not fit well with the fast-paced attack tactics used by the Swiss mercenary pike forces.

The Swiss remained primarily pikemen throughout the sixteenth century, but after that period they adopted similar infantry formations and tactics to other units in the armies in which they served. Accordingly, they began to deviate from their previously unique tactics, and they took a normal place in the battle line amongst the other infantry units.

End of military ascendancy

In the end, as proven at Marignano and Bicocca, the mass pike attack columns of the Swiss mercenaries proved to be too vulnerable to gunpowder weapons as firearms technology advanced, especially arquebusiers and artillery deployed on prepared ground (e.g., earthworks) and properly supported by other arms. These arquebusiers and heavy cannons scythed down the close-packed ranks of the Swiss squares in bloody heaps—at least, as long as the Swiss attack could be bogged down by earthworks or cavalry charges, and the vulnerable arquebusiers were backed up by melee infantry—pikemen, halberdiers, and/or swordsmen (Spanish sword-and-buckler men or the Doppelsöldner wielding the Zweihänder)—to defend them if necessary from the Swiss in close combat.

Other stratagems could also take the Swiss pikemen at a disadvantage. For instance, the Spanish rodeleros, also known as sword-and-buckler men, armed with steel rodelas and espadas and often wearing a helmet and a breastplate, were much better armed and armored for man-to-man close quarters combat. Accordingly, they could defeat the Swiss pike square by dashing under their unwieldy pikes and stabbing them. However, this tactic operated in support of allied pike squares and thus required the opposing pike square to be fully engaged in the chaos of the push of pike. Swiss pike columns that retained good formation were often able to beat back Spanish rodeleros with impunity, such as in the Battle of Seminara, in which the Spanish pike were heavily outnumbered.

After the Battle of Pavia

Despite the end of their supremacy circa 1525, the Swiss pike-armed mercenaries continued to be amongst the most capable close order infantry in Europe throughout the remainder of the sixteenth century. This was demonstrated by their battlefield performances in the service of the French monarchy during the French Wars of Religion, in particular at the Battle of Dreux, where a block of Swiss pikemen held the Huguenot army until the Catholic cavalry were able to counterattack.

Service in the French army

Swiss soldiers continued to serve as valued mercenaries with a number of European armies from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, in spite of extensive changes in tactics, drill and weapons. The most consistent and largest-scale employer of these troops was the French army, where the Swiss formed an elite part of the infantry. The Swiss Guards regiment, the most senior of the twelve Swiss mercenary regiments in French service, was essentially identical to the French Guards in organization and equipment, other than wearing a red uniform as opposed to the blue coats of the French corps. The Swiss adopted the musket in increasingly large numbers as the seventeenth century wore on, and abandoned the pike, their ancient trademark, altogether at around the same time as other troops in the French army, circa 1700. They also served in the New World: Samuel De Champlain's map of the Île Sainte-Croix (Saint Croix Island) settlement shows a barracks for the Swiss.[2]

The Swiss mercenaries were recruited according to contracts (capitulations) between the French Monarchy and Swiss cantons or individual noble families. By 1740 more than 12,000 Swiss soldiers were in French service. During the remainder of the eighteenth century, Swiss numbers varied according to need, reaching a peak of 20,000 during the Austrian War of Succession and falling to 12,300 after 1763.[3] In addition to the direct military value of employing Swiss in French service, a political purpose was achieved through the extension of French diplomatic and commercial influence over the neighbouring cantons.[4]

The Swiss soldier was paid at a higher level than his French counterpart but was subject to a harsher disciplinary code, administered by his own officers. The basis of recruitment varied according to regiment – in some units recruits were drawn exclusively from the Swiss inhabitants of specific cantons while in others German or French volunteers were accepted to make up shortfalls in the number of available Swiss. During the latter part of the 18th century, increasing reliance was placed on recruiting from the "children of the regiment" – the sons of Swiss soldiers who had married French women and stayed in France after their term of service had ended. The effect was to partially break down barriers between the Swiss and the French population amongst whom they were garrisoned. On the eve of the French Revolution the log-book of one Swiss regiment expressed concern that Franco-Swiss recruits were becoming prone to desertion as general discontent spread. French-speaking Swiss soldiers were generally to prove more susceptible to revolutionary propaganda than their German-speaking colleagues.[5]

At the outbreak of the French Revolution the Swiss troops were, as at least nominal foreigners, still considered more reliable than their French counterparts in a time of civil unrest. Accordingly, Swiss regiments made up a significant proportion of the royal troops summoned to Paris by Louis XVI in early July 1789. A detachment of Swiss grenadiers from the Salis-Samade Regiment was sent to reinforce the garrison of the Bastille prison shortly before it was besieged by the mob. The Swiss and other royal troops were subsequently withdrawn to their frontier garrisons. Over the next years The Ernest Regiment in particular faced a series of clashes with local citizens, culminating in a two day battle with Marseilles' militia in 1791.[6] This indication of growing popular resentment against the Swiss caused the Canton of Berne to recall the disarmed regiment. Another Swiss regiment, the Chateauvieux, played a major part in the Nancy affair (mutiny) of 1790[7] and 23 of its soldiers were executed, after trial by their own Swiss officers.[8] The Swiss Guard however remained loyal and was massacred on 10 August 1792, when the mob attacked the Tuileries Palace, although Louis XVI had already left the building. The eleven Swiss regiments of line infantry were disbanded under a decree passed by the French Assembly on 20 August 1792. Over three thousand Swiss soldiers transferred individually to French units and continued in service.[9] However, many of the rank and file returned to Switzerland, where measures had to be taken to provide them with relief and reintegration into the rural society from which most had been drawn.

Following the occupation of Switzerland by French revolutionary forces in 1798, a project to raise six demi-brigades of Swiss infantry for French service was initiated. However, recruitment proved difficult and by May 1799 only a quarter of the intended establishment of 18,000 had been raised.[10] Napoleon authorized the recruitment of a Swiss infantry regiment for French service in July 1805. A further three infantry regiments were created in October 1807, each including an artillery company. He specified that this newly raised Swiss Corps should comprise only citizens of Switzerland without "mingling in deserters or other foreigners".[11] The Swiss regiments fought well both in Spain (where they clashed at the Battle of Bailén with Swiss troops in the Spanish Army) and in Russia. During the retreat from Moscow Swiss losses amounted to 80% of their original numbers. The Swiss were allowed to keep the distinctive red coats which had distinguished them prior to 1792, with different facings identifying each regiment.

During the first Bourbon restoration of 1814–15, the grenadier companies of the by now under-strength four Swiss regiments undertook ceremonial guard duties in Paris. Upon Napoleon's return from Elba in 1815 the serving Swiss units were recalled to Switzerland on the grounds that a new contract signed with the government of Louis XVIII had now been rendered void. However, one composite regiment of Napoleon's Swiss veterans fought at Wavre during the Hundred Days.[12] Upon the second restoration of the monarchy in 1815 two regiments of Swiss infantry were recruited as part of the Royal Guard, while a further four served as line troops. All six Swiss units were disbanded in 1830 following the final overthrow of the Bourbon monarchy.

Service in the Spanish Army

Another major employer of Swiss mercenaries from the later 16th century on was Spain. After the Protestant Reformation, Switzerland was split along religious lines between Protestant and Catholic cantons. Swiss mercenaries from the Catholic cantons were thereafter increasingly likely to be hired for service in the armies of the Spanish Habsburg superpower in the later 16th century. The first regularly embodied Swiss regiment in the Spanish army was that of Walter Roll of Uri (a Catholic canton) in 1574, for service in the Spanish Netherlands, and by the middle of the 17th century there were a dozen Swiss regiments fighting for the Spanish army. From the latter part of the 17th century these could be found serving in Spain itself or in its overseas possessions.

The Swiss units saw active service against Portugal, against rebellions in Catalonia, in the War of the Spanish Succession, War of the Polish Succession, War of the Austrian Succession (in the fighting in Italy), and against Britain in the American Revolutionary War. By the 1790s there were about 13,000 men making up the Swiss contingents in a total Spanish army of 137,000. The practice of recruiting directly from the Catholic cantons was however disrupted by the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars. Recruiting agents substituted Germans, Austrians and Italians and in some regiments the genuine Swiss element dwindled to 100 or less.[13]

Their final role in Spanish service was against the French in the Peninsular War, in which the five Swiss regiments (Ruttiman, Yann, Reding, Schwaler and Courten) [14] mostly stayed loyal to their Spanish employers. At the Battle of Bailén, the Swiss regiments pressed into French service defected back to the Spanish Army under Reding. The year 1823 finally saw the end of Swiss mercenary service with the Spanish army.

The Swiss fighting in the ranks of the Spanish army generally followed its organization, tactics and dress. The Swiss regiments were however distinguished by their blue coats, in contrast to the white uniforms of the Spanish line infantry.[15]

Service in the Dutch Army

The Dutch employed many Swiss units at various dates during the 17th and 18th centuries.[16] In the early 18th century there were four regiments, and a ceremonial company of "Cent Suisses". They were mostly employed as garrison troops in peacetime, although the Republic sent Swiss regiments to Scotland in 1715 and 1745; in 1745, three battalions of the Swiss Hirtzel Regiment formed part of the Dutch contingent sent to serve in England as allies at the time of the Jacobite rising in Scotland that year.[17] With the threat of a French invasion in 1748, four additional regiments were taken into service, but that year, the War of Austrian Succession ended and three of these additional regiments were retired from service. In 1749 a regiment of "Zwitserche Guardes" (Swiss Guards) was raised, the recruits coming from the ranks of the existing Swiss infantry regiments; in 1787, these six regiments numbered a total of 9,600 men.[18]

Swiss regiments were employed by both the Dutch Republic and the Dutch East India Company for service in the Cape Colony and the East Indies. In 1772, the Regiment Fourgeoud was sent to Surinam to serve against the Marrons in the Surinam jungle. A narrative of this campaign written by John Gabriel Stedman, was later published. In 1781, the Regiment De Meuron was hired for Dutch service and in 1784 the Regiment Waldner. De Meurons' regiment was captured by the British in Ceylon, than taken into British service and sent to Canada, where it fought in the War of 1812.

With the abdication of the Stadhouder in 1795 and the forming of the Batavian Republic, the six Swiss regiments were disbanded in 1796. After the return of the Prince of Orange in 1813, four regiments of Swiss infantry, numbered 29 to 32 in the line, were raised, of which the 32nd Regiment served as a guard regiment performing guard duties at the Royal Palace in Amsterdam after 1815; however, these regiments were also disbanded in 1829.[19]

Service in the British Army

In 1781, Charles-Daniel de Meuron, a former colonel of the French Swiss Guard, founded his own mercenary regiment under the name Regiment de Meuron, first serving the Dutch East India Company, and from 1796, the British East India Company. Under British service, they fought in the Mysore Campaign of 1799, the Mediterranean and Peninsula Campaigns. After being stationed in Britain the regiment was posted to Canada, where it served in the War of 1812. It was finally disbanded in 1816.

The Regiment de Watteville was a Swiss regiment founded by Louis de Watteville and recruited from regiments that served between 1799 and 1801 in the Austrian army but in British pay. The Swiss soldiers were then transferred to British service. They fought in the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), mainly around the Mediterranean. They were based in Malta and then in Egypt from 1801 to 1803, fighting in Sicily and Naples. The regiment fought in the Battle of Maida in Italy in July 1806. Kept up to strength by Spanish and Portuguese recruits from 1811 to 1813, De Watteville's Regiment was involved in the Peninsular War in Spain, defending Cádiz during the Siege of Cádiz. The regiment sailed to Canada in 1813 to fight in the War of 1812. It saw service at Fort Erie and Oswego, before being disbanded in 1816.[20]

Capitulations and treaties

During the period of formalization of the employment of Swiss mercenaries in organized bodies from the late 16th century on, customary capitulations existed between employing powers and the Swiss cantons or noble families assembling and supplying these troops. Such contracts would generally cover specific details such as the numbers, quality, pay rates and equipment of recruits. Provisions were commonly made that Swiss soldiers would only serve under officers of their own nationality, would be subject to Swiss laws, would carry their own flags and would not be employed in campaigns that would bring them into conflict with Swiss in the service of another country.[21]

It has been claimed that such contracts might also contain a commitment that Swiss units would be returned if the confederation came under attack.[22] However, surviving capitulations from the 16th and 17th centuries are not known to contain provisions to this effect.

With the passing of the amendment to the Swiss Constitution of 1874 banning the recruitment of Swiss citizens by foreign states, such contractual relations ceased. Military alliances had already been banned under the Swiss constitution of 1848, though troops still served abroad when obliged by treaties. One such example were the Swiss regiments serving under Francis II of the Two Sicilies, who defended Gaeta in 1860 during the Italian War of Unification. This marked the end of an era.

Modern times

Since 1859, only one mercenary unit has been permitted, the Vatican's Swiss Guard, which has been protecting the Pope for the last five centuries, dressed in colourful uniforms, supposedly drawn by Michelangelo, reminiscent of the Swiss mercenary's heyday. Despite its being prohibited, individual Swiss citizens carried on the tradition of foreign military service into the twentieth century. This included 800 Swiss volunteers who fought with the Republican International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War, incurring heavy losses.[23]

Swiss citizens also served in the German Wehrmacht during the Second World War, although purely on an individual and voluntary basis. At least 2,000 Swiss fought for Germany during the war, mostly from the German-speaking cantons of Bern and Zurich, and many of them had dual German nationality. Besides the Wehrmacht some also joined the SS, particularly the 6th mountain division. Due to Switzerland's neutral status, their allegiances were considered illegal and in 1943 the government decided that those who cooperated with Germany would be deprived of their nationality. By 1945, there were only 29 such cases. A number of Swiss citizens were taken prisoner by the Soviet Union while fighting on the Eastern Front.[24]

The plot of George Bernard Shaw's comedy Arms and the Man (and of the operetta The Chocolate Soldier based on it) is focused on a fictional Swiss mercenary serving in the 1885 Serbo-Bulgarian War; there is, however, no evidence of actual such mercenaries in that war.

Notable Swiss mercenaries

- The artist Urs Graf

- Franz Adam Karrer

See also

- Military history of the Old Swiss Confederacy

- Beresinalied

- Mal du Suisse, a feeling of intense homesickness common with Swiss mercenaries

- Swiss army

References

- http://aregmultajelenben.shp.hu/hpc/web.php?a=aregmultajelenben&o=a_fekete_sereg_eloadas_6Tj

- Morison, Samuel Eliot, Samuel De Champlain, Father of New France, 1972, p. 44.

- Rene Chartrand, page 6 "Louis XV's Infantry – Foreign Infantry" ISBN 1-85532-623-X

- Tozzi, Christopher J. Nationalizing France's Army. p. 29. ISBN 9780813938332.

- Davin, Didier. Officers and Soldiers of Allied Swiss Troops in French Service 1785-1815. p. 5. ISBN 978-2-35250-235-7.

- Christopher J. Tozzi, pages 64-65 "Nationalizing France's Army. Foreign, Black and Jewish Troops in the French Military, 1715-1831, ISBN 978-0-8139-3833-2

- Christopher J. Tozzi, pages 58-59 "Nationalizing France's Army. Foreign, Black and Jewish Troops in the French Military, 1715-1831, ISBN 978-0-8139-3833-2

- Terry Courcelle, page 11 "French Revolutionary Infantry 1789–1802", ISBN 1-84176-660-7

- Christopher J. Tozzi, pages 82-83 and 119 "Nationalizing France's Army. Foreign, Black and Jewish Troops in the French Military, 1715-1831, ISBN 978-0-8139-3833-2

- D. Greentree & D. Campbell, pages 6–7 "Napoleon's Swiss Troops", ISBN 978-1-84908-678-3

- Philip Haythornthwaite, page 127 "Uniforms of the Retreat from Moscow 1812", ISBN 0-88254-421-7

- D. Greentree & D. Campbell, page 41 "Napoleon's Swiss Troops ", ISBN 978-1-84908-678-3

- Esdaile, Charles. Godoy's Army. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-911512-65-3.

- Rene Chartrand, page 20, "Spanish Army of the Napoleonic Wars 1793–1808", ISBN 1-85532-763-5

- Pivka, Otto von. Spanish Armies of the Napoleonic Wars. p. 22. ISBN 0-85045-243-0.

- An old Dutch saying is: "Geen geld, geen Zwitsers", from the French "point d'argent, point de Suisse"; it translates to: "No money, no Swiss [mercenaries]", meaning that you need money in order to wage war.

- Stuart Reid, pages 22–23 "Cumberland's Culloden Army 1745–46, ISBN 978 1 84908 846 6

- "Les Suisses dans l'Armée Néerlandaise dus XVIe au XXe sciècle" Number of officers and men in the various regiments (peacetime establishment): Regiment "Zwitsersche Guardes", 800 men; Regiment "De Stuerler", 1,800 men; Regiment "De May", 1,800; Regiment "Schmidt-Grünegg", 1,800; Regiment "Hirzel", 1,800; Regiment "De Stockar", 1,800.

- Rinaldo D. D'Ami, page 30 "World Uniforms in Colour – Volume 1: The European Nations", SBN 85059 031 0

- Major R. M. Barnes, page 84 "Military Uniforms of Britain & the Empire", Sphere Books London, 1972

- Page 619 "Cambridge Modern History, Volume 1: The Renaissance"

- McPhee, John (1983-10-31). "La Place de la Concorde Suisse-I". The New Yorker. p. 50. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- Clive H. Church, page 210 "A Concise History of Switzerland", Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-14382-0

- The hidden past of Swiss Nazi-era volunteers. Swissinfo. Published 7 January 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2019.

Books

- Ede-Borrett, Stephen, Swiss Regiments in the Service of France 1798-1815: Uniforms, Organization, Campaigns, Helion 2019

- Führer, H. R., and Eyer, R. P. (eds.), Schweizer in "Fremden Diensten", 2006. In German.

- Lienert, Meinrad, Schweizer Sagen und Heldengeschichten, 1915. In German.

- Miller, Douglas, The Swiss at War, 1979.

- Oman, Sir Charles, A History of the Art of War in the Sixteenth Century, 1937.

- Oman, Sir Charles, A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages, rev. ed. 1960.

- Richards, John, Landsknecht Soldier 1486–1550, 2002.

- Schaufelberger, Walter, Der Alte Schweizer und Sein Krieg: Studien Zur Kriegführung Vornehmlich im 15. Jahrhundert, 1987 (in German).

- Singer, P. W. "Corporate Warriors" 2003.

- Taylor, Frederick Lewis, The Art of War in Italy, 1494–1529, 1921.

- Wood, James B., The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562–76, 1996.

Online

- Fremde Dienste/Service étranger in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

Films

- Schweizer im Spanischen Bürgerkrieg (The Swiss in the Spanish Civil War), Director Richard Dindo, 1974 (English-language release 1982). In Swiss German with English sub-titles.

External links

- 500 Jahre Schlacht bei Hard, 1999?, on the SFwV SSGA website. (in German)

- Ancient Tactics Tested: Swiss Pike and Ancient Phalanx.

- 1499–1999, 1999, 500th anniversary of the Swabian War. (in German)