Jungfrau

The Jungfrau ("maiden, virgin"[note 3][1][2]), at 4,158 meters (13,642 ft) is one of the main summits of the Bernese Alps, located between the northern canton of Bern and the southern canton of Valais, halfway between Interlaken and Fiesch. Together with the Eiger and Mönch, the Jungfrau forms a massive wall of mountains overlooking the Bernese Oberland and the Swiss Plateau, one of the most distinctive sights of the Swiss Alps.

| Jungfrau | |

|---|---|

Northern wall | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 4,158 m (13,642 ft) |

| Prominence | 692 m (2,270 ft) [note 1] |

| Parent peak | Finsteraarhorn |

| Isolation | 8.2 km (5.1 mi) [note 2] |

| Coordinates | 46°32′12.5″N 7°57′45.5″E |

| Naming | |

| English translation | Maiden, Virgin, Young Woman |

| Language of name | German |

| Geography | |

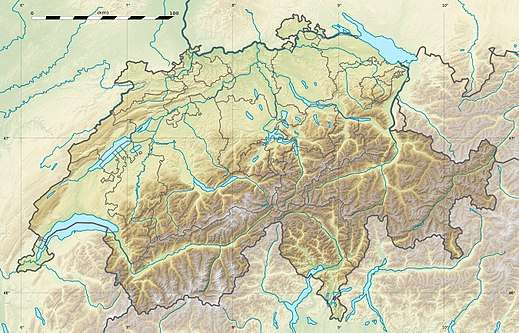

Jungfrau Location in Switzerland | |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Cantons | Bern and Valais |

| Parent range | Bernese Alps |

| Topo map | Swisstopo 1249 Finsteraarhorn |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 3 August 1811 by J. Meyer, H. Meyer, A. Volken, J. Bortis |

| Easiest route | basic snow/ice climb |

The summit was first reached on August 3, 1811, by the Meyer brothers of Aarau and two chamois hunters from Valais. The ascent followed a long expedition over the glaciers and high passes of the Bernese Alps. It was not until 1865 that a more direct route on the northern side was opened.

The construction of the Jungfrau railway in the early 20th century, which connects Kleine Scheidegg to the Jungfraujoch, the saddle between the Mönch and the Jungfrau, made the area one of the most-visited places in the Alps. Along with the Aletsch Glacier to the south, the Jungfrau is part of the Jungfrau-Aletsch area, which was declared a World Heritage Site in 2001.

Geographic setting

Politically, the Jungfrau is split between the municipalities of Lauterbrunnen (Bern) and Fieschertal (Valais). It is the third-highest mountain of the Bernese Alps after the nearby Finsteraarhorn and Aletschhorn, respectively 12 and 8 km away.[3] But from Lake Thun, and the greater part of the canton of Bern, it is the most conspicuous and the nearest of the Bernese Oberland peaks; with a height difference of 3,600 m between the summit and the town of Interlaken. This, and the extreme steepness of the north face, secured for it an early reputation for inaccessibility.

The Jungfrau is the westernmost and highest point of a gigantic 10 km wall dominating the valleys of Lauterbrunnen and Grindelwald. The wall is formed by the alignment of some of the biggest north faces in the Alps, with the Mönch (4,107 m) and Eiger (3,967 m) to the east of the Jungfrau, and overlooks the valleys to its north by a height of up to 3 km. The Jungfrau is approximately 6 km from the Eiger; with the summit of the Mönch between the two mountains, 3.5 km from the Jungfrau. The wall is extended to the east by the Fiescherwand and to the west by the Lauterbrunnen Wall.

The difference of altitude between the deep valley of Lauterbrunnen (800 m) and the summit is particularly visible from the area of Mürren. From the valley floor, west of the massif, the altitude gain is more than 3 km for a horizontal distance of 4 km.

The landscapes around the Jungfrau are extremely contrasted. Instead of the vertiginous precipices of the north-west, the south-east side emerges from the upper snows of the Aletsch Glacier at around 3,500 meters. The 20 km long valley of Aletsch on the south-east is completely uninhabited and also surrounded by other similar glacier valleys. The whole area constitutes the largest glaciated area in the Alps as well as in Europe.[4]

Climbing history

In 1811, the brothers Johann Rudolf (1768–1825) and Hieronymus Meyer, sons of Johann Rudolf Meyer (1739–1813), the head of a rich merchant family of Aarau, along with several servants and a porter picked up at Guttannen, first reached the Valais by way of the Grimsel, and crossed the Beich Pass, a glacier pass over the Oberaletsch Glacier, to the head of the Lötschen valley. There, they added two local chamois hunters, Alois Volken and Joseph Bortis, to their party and traversed the Lötschenlücke before reaching the Aletschfirn (the west branch of the Aletsch Glacier), where they established the base camp, north of the Aletschhorn. After the Guttannen porter was sent back alone over the Lötschenlücke, the party finally reached the summit of the Jungfrau by the Rottalsattel on August 3. They then recrossed the two passes named to their point of departure in Valais, and went home again over the Grimsel.[5][6]

The journey was a most extraordinary one for the time, and some persons threw doubts at its complete success. To settle these, another expedition was undertaken in 1812. In this the two sons, Rudolf (1791–1833) and Gottlieb (1793–1829), of Johann Rudolf Meyer, played the chief parts. After an unsuccessful attempt, defeated by bad weather, in the course of which the Oberaarjoch was crossed twice (this route being much more direct than the long detour through the Lötschental), Rudolf, with the two Valais hunters (Alois Volker and Joseph Bortis), a Guttannen porter named Arnold Abbühl, and a Hasle man, bivouacked on a depression on the southeast ridge of the Finsteraarhorn. Next day (August 16) the whole party attempted the ascent of the Finsteraarhorn from the Studer névé on the east by way of the southeast ridge, but Meyer, exhausted, remained behind. The following day the party crossed the Grünhornlücke to the Aletsch Glacier, but bad weather then put an end to further projects. At a bivouac, probably just opposite the present Konkordia Hut, the rest of the party, having come over the Oberaarjoch and the Grünhornlücke, joined the Finsteraarhorn party. Gottlieb, Rudolf's younger brother, had more patience than the rest and remained longer at the huts near the Märjelensee, where the adventurers had taken refuge. He could make the second ascent (September 3) of the Jungfrau, the Rottalsattel being reached from the east side as is now usual, and his companions being the two Valais hunters.[6]

The third ascent dates from 1828, when several men from Grindelwald, headed by Peter Baumann, planted their flag upon the summit. Next came the ascent by Louis Agassiz, James David Forbes, Heath, Desor, and Duchatelier in 1841, recounted by Desor in his Excursions et Séjours dans les Glaciers. Gottlieb Samuel Studer published an account of the next ascent made by himself and Bürki in 1842. In 1863, a party consisting of John Tyndall, J. J. Hornby, and T. H. Philpott, successfully reached the summit and returned to the base camp of the Faulberg (located near the actual position of the Konkordia Hut) in less than 11 hours.[7] (See also the next section, below.) In the same year Mrs Stephen Winkworth became the first woman to climb the Jungfrau. She also slept overnight in the Faulberg cave prior to the ascent as there was no hut at that time.[8]

Before the construction of the Jungfraujoch railway tunnel, the approach from the glaciers on the south side was very long. The first direct route from the valley of Lauterbrunnen was opened in 1865 by Geoffrey Winthrop Young, H. Brooke George with the guide Christian Almer. They had to carry ladders with them in order to cross the many crevasses on the north flank. Having spent the night on the rocks of the Schneehorn (3,402 m) they gained next morning the Silberlücke, the depression between the Jungfrau and Silberhorn, and thence in little more than three hours reached the summit. Descending to the Aletsch Glacier they crossed the Mönchsjoch, and passed a second night on the rocks, reaching Grindelwald next day. This route became a usual until the opening of the Jungfraujoch.[5][9]

The first winter ascent was made on 23 January 1874, by Meta Brevoort and W. A. B. Coolidge with guides Christian and Ulrich Almer.[10] They used a sled to reach the upper Aletsch Glacier, and were accompanied by Miss Brevoort's favorite dog, Tschingel.[5]

The Jungfrau was climbed via the west side for the first time in 1885 by Fritz and Heinrich von Allmen, Ulrich Brunner, Fritz Graf, Karl Schlunegger and Johann Stäger—all from Wengen. They ascended the Rottal ridge (Innere Rottalgrat) and reached the summit on 21 September. The more difficult and dangerous northeast ridge that connects the summit from the Jungfraujoch was first climbed on 30 July 1911 by Albert Weber and Hans Schlunegger.[10]

In July 2007 six Swiss Army recruits, part of the Mountain Specialists Division 1, died in an accident on the normal route. Although the causes of the deaths was not immediately clear, a report by the Swiss Federal Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research concluded that the avalanche risk was unusually high due to recent snowfall, and that there was "no other reasonable explanation" other than an avalanche for the incident.[11]

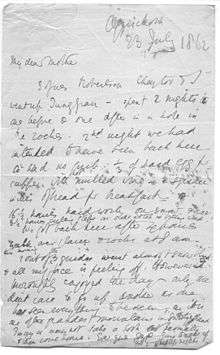

Ascent by James Phillpotts in 1863

In July 1863 James Surtees Phillpotts, a young graduate later to become Headmaster of Bedford School, climbed the Jungfrau together with his friends Chaytor and Robertson. It seems probable that the “T.H. Philpott” referred to in John Ball's 1869 guidebook (see above) was in fact James Phillpotts. The trio had three guides, Peter Baumann, Herr Kaufmann and Herr Rubi, and slept in the Faulberg cave during the nights before and after the ascent. Their expedition is described in a letter dated Sunday 26 July which James Phillpotts wrote to his friend and colleague Alexander Potts (subsequently Headmaster of Fettes College). The following extracts are from that letter.

The Virgin certainly did not smile on the poor "fools who rushed in" on her sacred heights, i.e. in plain British, we had the treadmill slog, the biting wind, the half frost-bitten feet and the flayed faces that generally attend an Alpine ascent.

We got to the Faulberg hole about dark, and enjoyed the coffee the longman (Kauffmann) made, as one would in a hole in a rock in a cold evening. The "Faulberg Nachtlager" consists of two holes and a vestibule to the upper hole. The Upper Hole in which we lodged just contained Chay[tor], the Guv [Robertson] and myself, stretched at full length on a little hay over a hard rock mattress, convex instead of concave at the point where one likes to rest one's weight. Chaytor was in the middle, and as we were very close was warm and slept. The Guv and I courted Nature's soft nurse in vain. At two we got up and methodically put our feet into the stocks, i.e. our boots, breakfasted and shivered, then started (unwashed of course, as the cold gave us malignant hydrophobia) a little after 3:30.

The hole was about 150 feet up one of the loose stone cliffs one now knows so well. So we groped our way down it and over the moraine – the stars still lingering, as day was just dawning. We could not start at 1:30, the proper time, as there was no moon and we wanted light as we had to tramp the glacier at once. Rubi led, and off we went, roped and in Indian file, in the old treadmill way over the slippery ploughed-field-like snow that lay on the upper glacier, for a pull without a check of one or two hours.

At last we came to the region of bergschrunds and crevasses. They seemed to form at first an impassable labyrinth, but gradually the guides wound in and out between the large rifts, which were exquisitely lovely with their overhanging banks of snow and glittering icicles, and then trod as on pins and needles over a snowbridge here and there, or had to take a jump over the more feasible ones – and we found ourselves at the foot of the mountain; trudged up on the snow which ought to have been crisp but was even then more or less fresh fallen and sloppy; had to creep over about three crevasses, and after a tiresome pull, dragging one leg after another out of ankle or knee deep snow, we got on a crest of snow at right angles to the slope we had just come up. That slope with its crevasses on one side, and on the other a shorter and much steeper one which led in a few steps to a precipice.

All along this crest went a snakelike long crevasse, for which we had continually to sound, and go first one side and then the other; then we got to the foot of the saddle. Some twenty or thirty steps, some cut, some uncut, soon took us up a kind of hollow, and we got on a little sloping plateau of some six feet large, where we left the grub and the knapsack, keeping my small flask of cognac only. Then up a steep ice slope, very steep I should say, down which the bits of ice cut out of the steps hopped and jumped at full gallop and then bounded over to some bottomless place which we could not see down. Their pace gave one an unpleasant idea of the possible consequence of a slip.

Here we encountered a biting bitter wind. Peter Baumann cut magnificent steps, at least he and Rubi did between them, the one improving on the other's first rough blows. After Rubi came Chaytor with Kauffmann behind him, then the Guv, and then myself, the tail of the string. Each step was a long lift from the last one, and as the snow was shallow they had to be cut in the ice which was like rock on this last slope.

Suddenly there burst upon us, on lifting our heads over the ridge, the green and cheerful valleys of Lauterbrunnen and Interlaken, of Grindelwald and a distant view of others equally beautiful stretching on for ever in one vast panorama. On the other side in grim contrast there was a wild and even awful scene. One gazed about one and tried in vain to see to the bottom of dark yawning abysses and sheer cliffs of ice or rock.[12]

Jungfraujoch and tourism

While the mountain peak was once difficult to access, the Jungfraubahn cog railway now goes to the Jungfraujoch railway station at 3,454 m (11,332 ft), the highest in Europe. The Jungfraujoch is the lowest pass between the Jungfrau and Mönch.

In 1893 Adolf Guyer-Zeller conceived of the idea for a railway tunnel to the Jungfraujoch to make the glaciated areas on the south more accessible. The building of the tunnel took 16 years and the summit station was not opened before 1912. The goal was in fact to reach the summit of the Jungfrau with an elevator from the highest railway station inside the mountain. The complete project was not realized because of the outbreak of the World War I.[5]

The train into the mountain leaves from Kleine Scheidegg, which can be reached by trains from Grindelwald and Lauterbrunnen via Wengen. The train enters the tunnel running eastward through the Eiger shortly above Kleine Scheidegg. Before arriving at the Jungfraujoch, it stops for a few minutes at two other stations, Eigerwand (on the north face of the Eiger) and Eismeer (on the south side), where passengers can see through the holes excavated from the mountain. The journey from Kleine Scheidegg to Jungfraujoch takes approximately 50 minutes including the stops; the downhill return journey taking only 35 minutes.

A large complex of tunnels and buildings has been constructed at the Jungfraujoch, mostly into the south side of the Mönch. There is a hotel, two restaurants, an observatory, a research station, a small cinema, a ski school, and the "Ice Palace", a collection of elaborate ice sculptures. Another tunnel leads outside to a flat, snow-covered area, where one can walk around and look down to the Konkordiaplatz and the Aletsch Glacier, as well as the surrounding mountains.

Apart from the Jungfraujoch, many facilities have been built in the two valleys north of the Jungfrau (the commonly named Jungfrau Region). In 1908, the first public cable car in the world opened at the foot of the Wetterhorn, but was closed seven years later.[13] The Schilthorn above Mürren or the Männlichen above Wengen offer good views of the Jungfrau and other summits.

Climbing routes

The normal route follows the traces of the first climbers, but the long approach on the Aletsch Glacier is no longer necessary. From the area of the Jungfraujoch the route to the summit takes only a few hours. Most climbers start from the Mönchsjoch Hut. After a traverse of the Jungfraufirn the route heads to the Rottalsattel (3,885 m), from where the southern ridge leads to the Jungfrau. It is not considered a very difficult climb but it can be dangerous on the upper section above the Rottalsattel, where most accidents happen.[5] The use of the Jungfrau railway can cause some acclimatization troubles as the difference of altitude between the railway stations of Interlaken and Jungfraujoch is almost 3 km.

See also

- List of 4000 metre peaks of the Alps

Notes and references

Notes

- Retrieved from the Swisstopo topographic maps. The key col is the Jungfraujoch (3,466 m)

- Retrieved from Google Earth. The nearest point of higher elevation is north of the Aletschhorn.

- The name Jungfrau ("maiden, virgin") of the peak is most likely derived from the name Jungfrauenberg given to Wengernalp, so named for the nuns of Interlaken Monastery, its historical owner, but the "virgin" peak was heavily romanticized as "goddess" or "priestess" in late 18th to 19th century Romanticism; after the first ascent in 1811 by Swiss alpinist Johann Rudolf Meyer, the peak was jokingly referred to as "Mme Meyer" (Mrs. Meyer).

References

- Therese Hänni (3 August 2011). "1811 verlor die Jungfrau ihre Unschuld". 20minuten online (in German). Zurich, Switzerland. Retrieved 2016-02-11.

- Daniel Anker: Jungfrau in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland, 2008-11-02.

- Swisstopo maps

- Jungfrau-Aletsch unesco.org. Retrieved 2010-02-08

- Helmut Dumler, Willi P. Burkhardt, Les 4000 des Alpes, ISBN 2-7003-1305-4.

- W. A. B. Coolidge, The Alps in Nature and History, p. 216, 1908.

- John Ball, The Alpine Guide: Central Alps, 1869, p. 92.

- The Times, August 20, 1863

- John Ball, The Alpine Guide: Central Alps, 1869, p. 74.

- Guide des Alpes bernoises, Swiss Alpine Club

- Questions remain a year after Jungfrau tragedy swissinfo.ch, retrieved 18 May 2009

- Letter by J.S. Phillpotts, edited extracts quoted in Us, A Family Album, Roger Gwynn, 2015.

- Berner Oberland strollingguides.co.uk, retrieved 1 May 2009

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jungfrau. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Jungfrau". SummitPost.org.

- Jungfrau at 4000er.de (in German)