Kusunda language

Kusunda (Kusanda) is a language isolate spoken by a handful of people in western and central Nepal. It has only recently been described in any detail.

| Kusunda | |

|---|---|

| Ban Raja | |

| mihaq | |

| Native to | Nepal |

| Region | Gandaki Zone |

| Ethnicity | 270 Kusunda (2011 census) |

Native speakers | 87 (2014)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | kgg |

| Glottolog | kusu1250[2] |

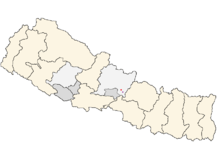

Ethnologue locations: (west) Dang and Pyuthan districts (dark grey) within Rapti Zone; (center) Tanahu District within Gandaki Zone EndangeredLanguages.com location: red WALS location: purple (Gorkha District) | |

Rediscovery

For decades the Kusunda language was thought to be on the verge of extinction, with little hope of ever knowing it well. The little material that could be gleaned from the memories of former speakers suggested that the language was an isolate, but without much evidence either way it was often classified along with its neighbors as Tibeto-Burman. However, in 2004 three Kusundas, Gyani Maya Sen, Prem Bahadur Shahi and Kamala Singh,[3] were brought to Kathmandu for help with citizenship papers. There, members of Tribhuvan University discovered that one of them, a native of Sakhi VDC in southern Rolpa District, was a fluent speaker of the language. Several of her relatives were also discovered to be fluent. There are now known to be at least seven or eight fluent speakers of the language, the youngest in her thirties.[4] However, the language is moribund, with no children learning it, as all Kusunda speakers have married outside their ethnicity.[4]

It was presumed that with the death of Rajamama Kusunda on 19 April 2018 the language went extinct.[5] However, Gyani Maiya Sen and her sister Kamala Kusunda survived him and further data has been collected.[6] The sisters together with author and researcher Uday Raj Aaley have been teaching interested children and adults the Kusunda language.[7]

Aaley, the facilitator and Kusunda language teacher, has authored the book "Kusunda Tribe and Dictionary".[8] The book has a compilation of over 1000 words from the Kusunda language.

Classification

Watters (2005) published a mid-sized grammatical description of the language, plus vocabulary, although there has been further work since.[9] Watters argued that Kusunda is indeed a language isolate, not just genealogically but also lexically, grammatically, and phonologically distinct from its neighbors. This would imply that Kusunda is a remnant of the languages spoken in northern India before the influx of Tibeto-Burman- and Indo-Iranian-speaking peoples, however it is not classified as a Munda or a Dravidian language. It thus joins Burushaski, Nihali and (potentially) the substrate of the Vedda language in the list of South Asian languages that do not fall into the main categories of Indo-European, Dravidian, Sino-Tibetan and Austroasiatic.

Before the recent discovery of active Kusunda speakers, there were several attempts to link the language to an established language family. B. K. Rana (2002) maintained that Kusunda is a Tibeto-Burman language as traditionally classified. Others have linked it to Munda (see Watters 2005); Yeniseian (Gurov 1989); Burushaski and Caucasian (Reinhard and Toba 1970; this would be a variant of Gurov's proposal if Sino-Caucasian is accepted); the Nihali isolate in central India (Fleming 1996, Whitehouse 1997); and again with Nihali, as part of the Indo-Pacific hypothesis (Whitehouse et al. 2004[10]).

There has been more recent work proposing a relationship between Kusunda, Yeniseian and Burushaski.[11]

Phonology

Vowels

Phonetically, Kusunda has six vowels in two harmonic groups, which are arguably three vowels phonemically: a word will normally have vowels from the upper (pink) or lower (green) set, but not both simultaneously. There are very few words that consistently have upper or lower vowels; most words may be pronounced either way, though those with uvular consonants require the lower set (as in many languages). There are a few words with no uvular consonants that still bar such dual pronunciations, though these generally only feature the distinction in careful enunciation.[12]

| Vowels | Front | Central | Back |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | ə | o |

| Open | a |

Consonants

Kusunda consonants seem to only contrast the active articulator, not where that articulator makes contact. For example, apical consonants may be dental, alveolar, retroflex, or palatal: /t/ is dental [t̪] before /i/, alveolar [t͇] before /e, ə, u/, retroflex [ʈ] before /o, a/, and palatal [c] when there is a following uvular, as in [coq] ~ [t͇ok] ('we').[12]

In addition, many consonants vary between stops and fricatives; for instance, /p/ seems to surface as [b] between vowels, while /b/ surfaces as [β] in the same environment. Aspiration appears to be recent to the language. Kusunda also lacks the retroflex consonant phonemes common to the region, and is unique in the region in having uvular consonants.[12]

| Labial | Coronal | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ɴʕ | ||

| Plosive | p~b b~β (pʰ bʱ) | t~d d (tʰ dʱ) | k~ɡ ɡ~ɣ (kʰ~x ɡʱ) | q~ɢ (qʰ) | ʔ | |

| Affricate | ts dz (tsʰ dzʱ) | |||||

| Fricative | s | ʁ~ʕ | h | |||

| Approximant | w | l | j | |||

| Flap | ɾ |

[ʕ] does not occur initially, and [ŋ] only occurs at the end of a syllable, unlike in neighboring languages. [ɴʕ] only occurs between vowels; it may be |ŋ+ʕ|.[12]

Pronouns

Kusunda has several cases, marked on nouns and pronouns three of which are nominative (Kusunda, unlike its neighbors, has no ergativity), genitive, and accusative persons.[12]

| Nominative | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| First person | tsi | tok |

| Second person | nu | nok |

| Third person | gina | |

| Genitive | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| First person | tsi, tsi-yi | tig-i |

| Second person | nu, ni-yi | ? nig-i |

| Third person | (gina-yi) | |

| Accusative | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| First person | tən-da | (toʔ-da) |

| Second person | nən-da | (noʔ-da) |

| Third person | gin-da | |

Other case suffixes include -ma "together with", -lage "for", -əna "from", -ga, -gə "at, in".

There are also demonstrative pronouns na and ta. Although it is not clear what the difference between them is, it may be animacy.

Subjects may be marked on the verb, though when they are, they may either be prefixed or suffixed. An example with am "eat", which is more regular than many verbs, in the present tense (-ən) is,

| am "eat" | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| First person | t-əm-ən | t-əm-da-n |

| Second person | n-əm-ən | n-əm-da-n |

| Third person | g-əm-ən | g-əm-da-n |

Other verbs may have a prefix ts- in the first person, or zero in the third.

See also

- Kusunda word list (Wiktionary)

References

- http://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/index.php

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Kusunda". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Rana, B.K. (2004-10-12). "Kusunda language does not fall in any family: Study". email with pasted news article. Himalayan News Service, Lalitpur, 2004-10-10. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- Watters, David E. 2005. Kusunda: a typological isolate in South Asia. In Yogendra Yadava, Govinda Bhattarai, Ram Raj Lohani, Balaram Prasain and Krishna Parajuli (eds.), Contemporary issues in Nepalese linguistics p. 375-396. Kathmandu: Linguistic Society of Nepal.

- "Rajamama, lone Kusunda language speaker, dies". Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- doi:10.17613/1zy2-k376

- "Resuscitating dying Kusunda language". The Kathmandu Post. 4 January 2019. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- "Book that traces Kusunda tribe's history hits shelves". The Kathmandu Post. 1 August 2017. Retrieved 17 September 2019.

- Donohue, Mark/Gautam, Bhoj Raj (2013). ‘Evidence and stance in Kusunda’. In: Nepalese Linguistics. Journal of the Linguistic Society of Nepal 28. 38–47.

- Paul Whitehouse; Timothy Usher; Merritt Ruhlen; William S.-Y. Wang (2004-04-13). "Kusunda: An Indo-Pacific language in Nepal". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (15): 5692–5695. doi:10.1073/pnas.0400233101. PMC 397480. PMID 15056764.

- van Driem, George (2014). ‘A Prehistoric Thoroughfare between the Ganges and the Himalayas’. In: Jamir, Tiatoshi/Hazarika, Manjil eds. 50 Years after Daojali-Hading: Emerging Perspectives in the Archaeology of Northeast India. New Delhi: Research India Press. 60–98.

- Watters (2005)

Further reading

- Reinhard, Johan and Sueyoshi Toba. (1970): A preliminary linguistic analysis and vocabulary of the Kusunda language. Summer Institute of Linguistics and Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu.

- Toba, Sueyoshi (2000). "Kusunda wordlists viewed diachronically". Journal of Nationalities of Nepal. 3 (5): 87–91.

- Toba, Sueyoshi (2000). "The Kusunda language revisited after 30 years". Journal of Nationalities of Nepal. 3 (5): 92–94.

- Watters, David E. 2005. Kusunda: a typological isolate in South Asia. In Yogendra Yadava, Govinda Bhattarai, Ram Raj Lohani, Balaram Prasain and Krishna Parajuli (eds.), Contemporary issues in Nepalese linguistics p. 375-396. Kathmandu: Linguistic Society of Nepal.

- Watters, David E (2006). ""Notes on Kusunda Grammar: A Language Isolate of Nepal".PDF". Himalayan Linguistics Archive. 3: 1–182. External link in

|title=(help) - Rana, B.K. Significance of Kusundas and their language in the Trans-Himalayan Region. Mother Tongue. Journal of the Association for the Study of Language in Prehistory (Boston) IX, 2006, 212-218

- Donohue, Mark; Raj Gautam, Bhoj (2013). "Evidence and Stance in Kusunda" (PDF). Nepalese Linguistics. 28: 38–47.

External links

- "Nepal's mystery language on the verge of extinction", Bimal Gautum, BBC, 12 May 2012

- Kusunda language does not fall in any family: Study, Himalayan News Service, Lalitpur, October 10, 2004

- Partial bibliography

- Portal to Asian Internet Resources (Project). Bibliography for Seldom Studied and Endangered South Asian Languages. Germany: John Peterson.

- Rana, B.K. A Short note on Kusunda language. Janajati 2/4, 2001.

- Rana, B.K., Linguistic Society of Nepal New Materials on Kusunda Language, Presented to the Fourth Round Table International Conference on Ethnogenesis of South and Central Asia, Harvard University, Cambridge MA, USA. May 11-13, 2002

- Rana, B.K., Significance of Kusundas and Their Language in the Trans-Himalayan Region, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, October 21-22, 2006

- Watters, David. Notes on Kusunda Grammar: A language isolate of Nepal. Himalayan Linguistics Archive 3. 1-182, 2006

- "Obscure language isolate will die with this woman". The Hot Word - Hot & Trending Words Daily Blog at Dictionary.com. 2012-06-03. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- Kusunda linguistics (ANU)