Kra–Dai languages

The Kra–Dai languages (also known as Tai–Kadai, Daic and Kadai) are a language family of tonal languages found in Mainland Southeast Asia, southern China, and Northeast India. They include Thai and Lao, the national languages of Thailand and Laos respectively.[2] Around 93 million people speak Kra–Dai languages, 60% of whom speak Thai.[3] Ethnologue lists 95 languages in the family, with 62 of these being in the Tai branch.[4]

| Kra–Dai | |

|---|---|

| Tai–Kadai, Daic, Kadai | |

| Geographic distribution | southern China, Hainan Island, Indochina and Northeast India |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language | Proto-Kra–Dai |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | taik1256[1] |

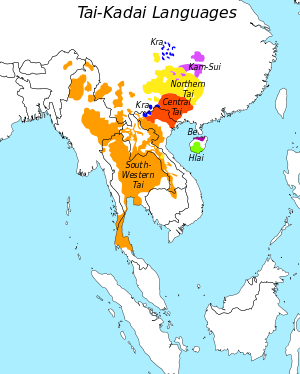

Distribution of the Tai–Kadai language family. | |

The high diversity of Kra–Dai languages in southern China points to the origin of the Kra–Dai language family in southern China. The Tai branch moved south into Southeast Asia only around 1000 AD. Genetic and linguistic analysis show great homogeneity between Kra–Dai speaking people in Thailand.[5]

Names

The name "Kra–Dai" was proposed by Weera Ostapirat (2000), as Kra and Dai are the reconstructed autonyms of the Kra and Tai branches respectively.[6] "Kra–Dai" has since been used by the majority of specialists working on Southeast Asian linguistics, including Norquest (2007),[7] Pittayaporn (2009),[8][9] Baxter & Sagart (2014),[10] and Enfield & Comrie (2015).[11]

The name "Tai–Kadai" is used in many references, as well as Ethnologue and Glottolog, but Ostapirat (2000) and others suggest that it is problematic and confusing, preferring the name "Kra–Dai" instead.[6] "Tai–Kadai" comes from an obsolete bifurcation of the family into two branches, Tai and Kadai, which had first been proposed by Paul K. Benedict (1942).[12] In 1942, Benedict placed three Kra languages (Gelao, Laqua (Qabiao) and Lachi) together with Hlai in a group that he called "Kadai", from ka, meaning "person" in Gelao and Laqua (Qabiao), and Dai, a form of a Hlai autonym.[12] Benedict's (1942) "Kadai" group was based on his observation that Kra and Hlai languages have Austronesian-like numerals. However, this classification is now universally rejected as obsolete after Ostapirat (2000) demonstrated the coherence of the Kra branch, which does not subgroup with the Hlai branch as Benedict (1942) had proposed. "Kadai" is sometimes used to refer to the entire Kra–Dai family, including by Solnit (1988).[13][14] Adding to the confusion, some other references restrict the usage of "Kadai" to only the Kra branch of the family.

The name "Daic" is used by Roger Blench (2008).[15]

Internal classification

Kra–Dai consists of at least five well established branches, namely Kra, Kam–Sui, Tai, Be and Hlai (Ostapirat 2005:109).

- Tai (southern China and Southeast Asia; by far the largest branch)

- Kra (southern China, northern Vietnam; called Kadai in Ethnologue)

- Kam–Sui (Guizhou and Guangxi, China)

- Be (Hainan; possibly also includes Jizhao of Guangdong)

- Hlai (Hainan)

Chinese linguists have also proposed a Kam–Tai group that includes Kam–Sui, Tai and Be.[16][17]

Kra–Dai languages that are not securely classified, and may constitute independent Kra–Dai branches, include the following.

- Lakkia and Biao, which may or may not subgroup with each other, are difficult to classify due to aberrant vocabulary, but are sometimes classified as sisters of Kam–Sui (Solnit 1988).[13]

- Jiamao of southern Hainan, China is an aberrant Kra–Dai language traditionally classified as a Hlai language, although Jiamao contains many words of non-Hlai origin.

- Jizhao of Guangdong, China is currently unclassified within Kra–Dai, but appears to be most closely related to Be (Ostapirat 1998).[18]

Kra–Dai languages of mixed origins are:

- Hezhang Buyi: Northern Tai and Kra

- E: Northern Tai and Pinghua Chinese

- Caolan: Northern Tai and Central Tai

- Sanqiao: Kam–Sui, Hmongic and Chinese

- Jiamao: Hlai and other unknown elements (Austroasiatic?)

Edmondson and Solnit (1988)

An early but influential classification, with the traditional Kam–Tai clade, was Edmondson and Solnit's classification from 1988:[14][19]

| Kra–Dai |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This classification is used by Ethnologue, though by 2009 Lakkia was made a third branch of Kam–Tai and Biao was moved into Kam–Sui.

Ostapirat (2005); Norquest (2007)

Weera Ostapirat (2005:108) suggests the possibility of Kra and Kam–Sui being grouped together as Northern Kra–Dai, and Hlai with Tai as Southern Kra–Dai.[20] Norquest (2007) has further updated this classification to include Lakkia and Be. Norquest notes that Lakkia shares some similarities with Kam–Sui, while Be shares some similarities with Tai. Norquest (2007:15) notes that Be shares various similarities with Northern Tai languages in particular.[7] Following Ostapirat, Norquest adopts the name Kra–Dai for the family as a whole. The following tree of Kra–Dai is from Norquest (2007:16).

| Kra–Dai |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Additionally, Norquest (2007) also proposes a reconstruction for Proto-Southern Kra–Dai.

External relationships

Sino-Tai

The Kra–Dai languages were formerly considered to be part of the Sino-Tibetan family, partly because they contain large numbers of words that are similar to Sino-Tibetan languages. However, these words are seldom found in all branches of the family and do not include basic vocabulary, indicating that they are old loan words.[20] Outside China, the Kra–Dai languages are now classified as an independent family. In China, they are called Zhuang–Dong languages and are generally included, along with the Hmong–Mien languages, in the Sino-Tibetan family.[21] It is still a matter of discussion among Chinese scholars whether Kra languages such as Gelao, Qabiao and Lachi can be included in Zhuang–Dong, since they lack the Sino-Tibetan similarities that are used to include other Zhuang–Dong languages in Sino-Tibetan.

Austro-Tai

Several scholars have presented suggestive evidence that Kra–Dai is related to or a branch of the Austronesian language family.[23] There are a number of possible cognates in the core vocabulary displaying regular sound correspondences. Among proponents, there is yet no agreement as to whether they are a sister group to Austronesian in a family called Austro-Tai, a back-migration from Taiwan to the mainland, or a later migration from the Philippines to Hainan during the Austronesian expansion.[24]

The inclusion of Japanese in the Austro-Tai family, as proposed by Paul K. Benedict in the late 20th century,[25] is not supported by the current proponents of the Austro-Tai hypothesis.

Hmong-Mien

Kosaka (2002) argued specifically for a Miao–Dai family. He argues that there is much evidence for a genetic relation between Hmong-Mien and Kra–Dai languages. He further suggests that similarities between Kra–Dai and Austronesian are because of later areal contact in coastal areas of eastern and southeastern China or an older ancestral relation (Proto-Eastasian).[26]

Japonic languages

Vovin (2014) proposed that the location of the Japonic Urheimat (linguistic homeland) is in Southern China. Vovin argues for typological evidence that Proto-Japanese may have been a monosyllabic, SVO syntax and isolating language, which are also characteristic of Tai–Kadai languages. According to him, these common features are however not due to a genetic relationship, but rather the result of intense contact.[27]

Reconstruction

| Proto-Kra–Dai | |

|---|---|

| Reconstruction of | Kra–Dai languages |

| Lower-order reconstructions | |

No full reconstruction of Proto-Kra–Dai has been published to date, although tentative reconstructions of many Proto-Kra–Dai roots have been attempted from time to time. Some Proto-Kra–Dai forms have been reconstructed by Benedict (1975)[28] and Wu (2002).[29] A reconstruction of Proto-Kam–Tai (i.e., a proposed grouping that contains all of Kra–Dai without Kra, Hlai, and Jiamao) has also been undertaken by Liang & Zhang (1996).[16]

Weera Ostapirat (2018a)[30] reconstructs disyllabic forms for Proto-Kra–Dai, rather than sesquisyllabic or purely monosyllabic forms. His Proto-Kra–Dai reconstructions also contains the finals */-c/ and */-l/.[31] Ostapirat (2018b:113)[32] lists the following of his own Proto-Kra–Dai reconstructions.

Notes:

- */K-/: either /k-/ or /q-/

- */C-/: unspecified consonant

- */T-/ and */N-/ are distinct from */t-/ and */n-/.

| Gloss | Proto-Kra–Dai |

|---|---|

| blood | *pɤlaːc |

| bone | *Kudɤːk |

| ear | *qɤrɤː |

| eye | *maTaː |

| hand | *(C)imɤː |

| nose | *(ʔ)idaŋ |

| tongue | *(C)əmaː |

| tooth | *lipan |

| dog | *Kamaː |

| fish | *balaː |

| horn | *paquː |

| louse | *KuTuː |

| fire | *(C)apuj |

| stone | *KaTiːl |

| star | *Kadaːw |

| water | *(C)aNam |

| I (1.SG) | *akuː |

| Thou (2.SG) | *isuː; amɤː |

| one | *(C)itsɤː |

| two | *saː |

| die | *maTaːj |

| name | *(C)adaːn |

| full | *pətiːk |

| new | *(C)amaːl |

See also

- Austric languages

- Austro-Tai languages

- Hmong–Mien languages

- Proto-Hlai language

- Proto-Hmong–Mien language

- Proto-Kam–Sui language

- Proto-Kra language

- Proto-Sino-Tibetan language

- Proto-Tai language

- Sino-Austronesian languages

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Tai–Kadai". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Diller, Anthony, Jerry Edmondson, Yongxian Luo. (2008). The Tai–Kadai Languages. London [etc.]: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1457-5

- "Taikadai". www.languagesgulper.com. Retrieved 2017-10-15.

- Ethnologue Tai–Kadai family tree

- Srithawong, Suparat; Srikummool, Metawee; Pittayaporn, Pittayawat; Ghirotto, Silvia; Chantawannakul, Panuwan; Sun, Jie; Eisenberg, Arthur; Chakraborty, Ranajit; Kutanan, Wibhu (July 2015). "Genetic and linguistic correlation of the Kra-Dai-speaking groups in Thailand". Journal of Human Genetics. 60 (7): 371–380. doi:10.1038/jhg.2015.32. ISSN 1435-232X. PMID 25833471.

- Ostapirat, Weera. (2000). "Proto-Kra." Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 23 (1): 1-251.

- Norquest, Peter K. 2007. A Phonological Reconstruction of Proto-Hlai. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona.

- Pittayaporn, Pittayawat. 2009. The phonology of Proto-Tai. Ph.D. Thesis, Cornell University

- Peter Jenks and Pittayawat Pittayaporn. Kra-Dai Languages. Oxford Bibliographies in "Linguistics", Ed. Mark Aranoff. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Baxter, William H.; Sagart, Laurent (2014), Old Chinese: A New Reconstruction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-994537-5.

- N. J. Enfield and B. Comrie, Eds. 2015. Languages of Mainland Southeast Asia: The State of the Art. Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter.

- Benedict, Paul K. (1942). "Thai, Kadai, and Indonesian: A New Alignment in Southeastern Asia". American Anthropologist. 44 (4): 576–601. doi:10.1525/aa.1942.44.4.02a00040. JSTOR 663309.

- Solnit, David B. 1988. "The position of Lakkia within Kadai." In Comparative Kadai: Linguistic studies beyond Tai, Jerold A. Edmondson and David B. Solnit (eds.). pages 219-238. Summer Institute of Linguistics Publications in Linguistics 86. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington.

- Edmondson, Jerold A. and David B. Solnit, editors. 1988. Comparative Kadai: Linguistic studies beyond Tai. Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington Publications in Linguistics, 86. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. vii, 374 p.

- Blench, Roger. 2008. The Prehistory of the Daic (Tai-Kadai) Speaking Peoples. Presented at the 12th EURASEAA meeting Leiden, 1–5 September 2008. (PPT slides)

- Liang Min 梁敏 & Zhang Junru 张均如. 1996. Dongtai yuzu gailun 侗台语族概论 / An introduction to the Kam–Tai languages. Beijing: China Social Sciences Academy Press 中国社会科学出版社. ISBN 9787500416814

- Ni Dabai 倪大白. 1990. Dongtai yu gailun 侗台语概论 / An introduction to the Kam-Tai languages. Beijing: Central Nationalities Research Institute Press 中央民族学院出版社.

- Ostapirat, W. (1998). A Mainland Bê Language? / 大陆的Bê语言?. Journal of Chinese Linguistics, 26(2), 338-344

- Edmondson, Jerold A. and David B. Solnit, editors. 1997. Comparative Kadai: the Tai branch. Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington Publications in Linguistics, 124. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. vi, 382 p.

- Ostapirat, Weera. (2005). "Kra–Dai and Austronesian: Notes on phonological correspondences and vocabulary distribution", pp. 107–131 in Sagart, Laurent, Blench, Roger & Sanchez-Mazas, Alicia (eds.), The Peopling of East Asia: Putting Together Archaeology, Linguistics and Genetics. London/New York: Routledge-Curzon.

- Luo, Yongxian. 2008. Sino-Tai and Tai-Kadai: Another look. In Anthony V. N. Diller and Jerold A. Edmondson and Yongxian Luo (eds.), The Tai-Kadai Languages, 9-28. London & New York: Routledge.

- Blench, Roger (2018). Tai-Kadai and Austronesian are Related at Multiple Levels and their Archaeological Interpretation (draft).

The volume of cognates between Austronesian and Daic, notably in fundamental vocabulary, is such that they must be related. Borrowing can be excluded as an explanation

- Sagart, Laurent (2004). "The higher phylogeny of Austronesian and the position of Tai–Kadai" (PDF). Oceanic Linguistics. 43: 411–440.

- Ostapirat, Weera (2013). "Austro-Tai revisited" (PDF). 23rd Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistic Society (SEALS 2013).

- Benedict, Paul K. (1990). Japanese/Austro-Tai. Karoma. ISBN 978-0-89720-078-3.

- Kosaka, Ryuichi. 2002. "On the affiliation of Miao-Yao and Kadai: Can we posit the Miao-Dai family." Mon-Khmer Studies 32:71-100.

- Vovin, Alexander (2014). Out Of Southern China? --some linguistic and philological musings on the possible Urheimat of the Japonic language family-- XXVIIes Journées de Linguistique d'Asie Orientale 26-27 juin 2014.

- Benedict, Paul K. 1975. Austro-Thai: language and culture, with a glossary of roots. New Haven: Human Relations Area Files Press.

- Wu, Anqi 吴安其. 2002. Hanzangyu tongyuan yanjiu 汉藏语同源研究. Beijing: Minzu University Press 中央民族大学出版社. ISBN 7-81056-611-3

- Ostapirat, Weera. 2018a. Reconstructing Disyllabic Kra-Dai. Paper presented at the 28th Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, held May 17–19, 2018 in Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

- Ostapirat, Weera. 2009. Proto-Tai and Kra–Dai finals *-l and *-c. Journal of Language and Culture Vol. 28 No. 2 (July - December 2009).

- Ostapirat, Weera. 2018b. "Macrophyletic Trees of East Asian Languages Re examined." In Let's Talk about Trees, ed. by Ritsuko Kikusawa and Lawrence A. Reid. Osaka: Senri Ethnological Studies, Minpaku. doi:10.15021/00009006

- Edmondson, J.A. and D.B. Solnit eds. 1997. Comparative Kadai: the Tai branch. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics and the University of Texas at Arlington. ISBN 0-88312-066-6

- Blench, Roger. 2004. Stratification in the peopling of China: how far does the linguistic evidence match genetics and archaeology? Paper for the Symposium "Human migrations in continental East Asia and Taiwan: genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence". Geneva June 10–13, 2004. Université de Genève.

Further reading

- Chamberlain, James R. (2016). Kra-Dai and the Proto-History of South China and Vietnam. Journal of the Siam Society, 104, 27-76.

- Diller, A., J. Edmondson, & Yongxian Luo, ed., (2005). The Tai–Kadai languages. London [etc.]: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1457-X

- Edmondson, J. A. (1986). Kam tone splits and the variation of breathiness.

- Edmondson, J. A., & Solnit, D. B. (eds.) (1988). Comparative Kadai: linguistic studies beyond Tai. Summer Institute of Linguistics publications in linguistics, no. 86. Arlington, TX: Summer Institute of Linguistics. ISBN 0-88312-066-6

- Mann, Noel, Wendy Smith and Eva Ujlakyova. 2009. Linguistic clusters of Mainland Southeast Asia: an overview of the language families. Chiang Mai: Payap University.

- Ostapirat, Weera. (2000). "Proto-Kra." Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 23 (1): 1-251.

- Somsonge Burusphat, & Sinnott, M. (1998). Kam–Tai oral literatures: collaborative research project between. Salaya Nakhon Pathom, Thailand: Institute of Language and Culture for Rural Development, Mahidol University. ISBN 974-661-450-9