Tyrsenian languages

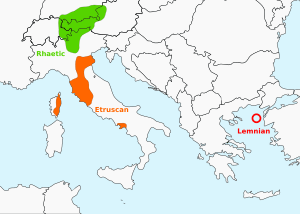

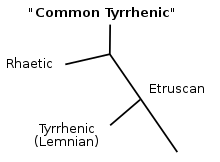

Tyrsenian (also Tyrrhenian), named after the Tyrrhenians (Ancient Greek, Ionic: Τυρσηνοί, Tursēnoi), is a hypothetical extinct family of closely related ancient languages proposed by Helmut Rix (1998), which consists of the Etruscan language of northern, central and south-western Italy; the Rhaetic language of the Alps, named after the Rhaetian people; and the Lemnian language of the Aegean Sea. Camunic in northern Lombardy, in between Etruscan and Rhaetic, may belong here too, but the material is very scant.[1] Tyrsenian languages are considered Pre-Indo-European.[2]

| Tyrsenian | |

|---|---|

| Tyrrhenian | |

| Geographic distribution | Italy, Switzerland, Slovenia, Germany, Austria and Greece (island of Lemnos) |

| Linguistic classification | Pre-Indo-European, Paleo-European, proposed language family |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | None |

Approximate area of Tyrsenian languages | |

History

In 1998 the German linguist Helmut Rix proposed the Tyrrhenian linguistic family, which includes the Etruscan language spoken in Etruria, the Rhaetian language spoken in the Alps, together with the Lemnian language attested by a small number of inscriptions on the Greek island of Lemnos in the Aegean Sea, languages that Rix identifies in close relation. Rix assumes a date for Proto-Tyrsenian in the last quarter of the 2nd millennium BC.[3] Rix's Tyrsenian family has been confirmed by Stefan Schumacher,[4][5][6][7] Norbert Oettinger,[8] Carlo De Simone[9] and Simona Marchesini.[10] Common features between Etruscan, Rhaetian, Lemnian have been found in morphology, phonology, and syntax.[11] On the other hand, few lexical correspondences are documented, at least partly due to the scanty number of Rhaetian and Lemnian texts. Carlo De Simone and Simona Marchesini have proposed a very ancient date at which these languages split, before the Bronze Age, much earlier than was suggested by Rix.[10][12][13] This would provide an additional explanation for the low number of lexical correspondences.[14] The Tyrsenian family, or Common Tyrrhenic, in this case is often considered to be Paleo-European and to predate the arrival of Indo-European languages in southern Europe.[15]

Strabo's (Geography V, 2) citation from Anticlides attributes a share in the foundation of Etruria to the Pelasgians of Lemnos and Imbros.[16][17] The Pelasgians are also referred to by Herodotus as settlers in Lemnos, after they were expelled from Attica by the Athenians.[18] Apollonius of Rhodes mentioned an ancient settlement of Tyrrhenians on Lemnos in his Argonautica (IV.1760), written in the third century BC, in an elaborate invented aition of Kalliste or Thera (modern Santorini): in passing, he attributes the flight of "Sintian" Lemnians to the island Kalliste to "Tyrrhenian warriors" from the island of Lemnos.

Alternatively, the Lemnian language could have arrived in the Aegean Sea during the Late Bronze Age, when Mycenaean rulers recruited groups of mercenaries from Sicily, Sardinia and various parts of the Italian peninsula.[19]

Languages

- Etruscan: 13,000 inscriptions, the overwhelming majority of which have been found in Italy; the oldest Etruscan inscription dates back to the 8th century BC, the most recent one is dated to the 1st century AD.[20]

- Rhaetic: 300 inscriptions, the overwhelming majority of which have found in the Central Alps; the oldest Rhaetic inscription dates back to the 6th century BC.[2][20]

- Lemnian: 2 inscriptions plus a small number of extremely fragmentary inscriptions; the oldest Lemnian inscription dates back to the late 6th century BC.[20]

- Camunic: probably related to Rhaetic, about 170 inscriptions found in the Central Alps; the oldest Camunic inscriptions dates back to the 5th century BC.[20]

Evidence

Cognates common to Rhaetic and Etruscan are:

- Etr. zal, Raet. zal, "two";

- Etr. -(a)cvil, Raet. akvil, "gift";

- Etr. zinace, Raet. t'inaχe, "he made".

- a genitive suffix -s in all three languages;

- a second genitive suffix -a in Rhaetic, -(i)a in Etruscan;

- the past active participle -ce in Etruscan, -ku in Rhaetic.

Cognates common to Lemnian and Etruscan are:

- dative-case suffixes *-si, and *-ale, attested on the Lemnos Stele (Hulaie-ši "for Hulaie", Φukiasi-ale "for the Phocaean") and in Etruscan inscriptions (e.g. aule-si "To Aule" on the Cippus Perusinus);

- a past tense suffix *-a-i (Etruscan -⟨e⟩ as in ame "was" ( ← *amai); Lemnian -⟨ai⟩ as in šivai "lived").

- Etr. avils maχs śealχisc "and aged sixty-five", Lem. aviš sialχviš "aged sixty"

Suggested relationships to other families

Aegean language family

A larger Aegean family including Eteocretan, Minoan and Eteocypriot has been proposed by G. M. Facchetti, and is supported by S. Yatsemirsky, referring to some alleged similarities between on the one hand Etruscan and Lemnian, and on the other hand some languages such as Minoan and Eteocretan. If these languages could be shown to be related to Etruscan and Rhaetic, they would constitute a pre-Indo-European language family stretching from (at the very least) the Aegean islands and Crete across mainland Greece and the Italian peninsula to the Alps. Facchetti proposes a hypothetical language family derived from Minoan in two branches. From Minoan he proposes a Proto-Tyrrhenian from which would have come the Etruscan, Lemnian and Rhaetic languages. James Mellaart has proposed that this language family is related to the pre-Indo-European languages of Anatolia, based upon place name analysis.[21] From another Minoan branch would have come the Eteocretan language.[22][23] T. B. Jones proposed in 1950 reading of Eteocypriot texts in Etruscan, which was refuted by most scholars but gained popularity in the former Soviet Union.

Anatolian languages

A relation with the Anatolian languages within Indo-European has been proposed,[lower-alpha 1][25] but is not accepted.[26] If these languages are an early Indo-European stratum rather than pre-Indo-European, they would be associated with Krahe's Old European hydronymy and would date back to a Kurganization during the early Bronze Age.

Northeast Caucasian languages

A number of mainly Soviet or post-Soviet linguists, including Sergei Starostin,[27] suggested a link between the Tyrrhenian languages and the Northeast Caucasian languages in an Alarodian language family, based on claimed sound correspondences between Etruscan, Hurrian and Northeast Caucasian languages, numerals, grammatical structures and phonologies. Most linguists, however, doubt that the language families are related, or believe that the evidence is far from conclusive.

Extinction

The language group would have died out around the 3rd century BC in the Aegean (by assimilation of the speakers to Greek), and as regards Etruscan around the 1st century AD in Italy (by assimilation to Latin). Finally, Rhaetic died out in the 3rd century AD, by assimilation to Vulgar Latin, and later to Germanic in the north.

See also

- Camunic language (probably Raetic)

- North Picene language

- Elymian language (probably Indo-European)

- Sicanian language

- Paleo-Sardinian language (also called Paleosardinian, Protosardic, Nuraghic language)

- Old European hydronymy

Notes

- Steinbauer tries to relate both Etruscan and Rhaetic to Anatolian.[24]

References

- Blackwell reference.

- Simona Marchesini (translation by Melanie Rockenhaus) (2013). "Raetic (languages)". Mnamon - Ancient Writing Systems in the Mediterranean. Scuola Normale Superiore. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Rix, Helmut (2008). "Etruscan". In Woodard, Roger D. (ed.). The Ancient Languages of Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 141–164. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511486814.010. ISBN 9780511486814.

- Schumacher, Stefan (1994) Studi Etruschi in Neufunde ‘raetischer’ Inschriften Vol. 59 pp. 307-320 (German)

- Schumacher, Stefan (1994) Neue ‘raetische’ Inschriften aus dem Vinschgau in Der Schlern Vol. 68 pp. 295-298 (German)

- Schumacher, Stefan (1999) Die Raetischen Inschriften: Gegenwärtiger Forschungsstand, spezifische Probleme und Zukunfstaussichten in I Reti / Die Räter, Atti del simposio 23-25 settembre 1993, Castello di Stenico, Trento, Archeologia delle Alpi, a cura di G. Ciurletti - F. Marzatico Archaoalp pp. 334-369 (German)

- Schumacher, Stefan (2004) Die Raetischen Inschriften. Geschichte und heutiger Stand der Forschung Archaeolingua. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft. (German)

- Oettinger, Norbert (2010) "Seevölker und Etrusker", in Yoram Cohen, Amir Gilan, and Jared L. Miller (eds.) Pax Hethitica Studies on the Hittites and their Neighbours in Honour of Itamar Singer (in German), Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 233–246

- de Simone, Carlo (2009) La nuova iscrizione tirsenica di Efestia in Aglaia Archontidou, Carlo de Simone, Emanuele Greco (Eds.), Gli scavi di Efestia e la nuova iscrizione ‘tirsenica’, Tripodes 11, 2009, pp. 3-58. Vol. 11 pp. 3-58 (Italian)

- De Simone, Carlo; Marchesini, Simona, eds. (2013). La lamina di Demlfeld. Mediterranea. Quaderni annuali dell'Istituto di Studi sulle Civiltà italiche e del Mediterraneo antico del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (in Italian). Supplemento 8. Pisa – Roma: Serra Editore.

- Kluge Sindy, Salomon Corinna, Schumacher Stefan (2013–2018). "Raetica". Thesaurus Inscriptionum Raeticarum. Department of Linguistics, University of Vienna. Retrieved 26 July 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Marchesini, Simona (2013). "I rapporti etrusco/retico-italici nella prima Italia alla luce dei dati linguistici: il caso della "mozione" etrusca". Rivista storica dell'antichità (in Italian). Bologna: Pàtron editore. 43: 9–32. ISSN 0300-340X.

- Marchesini, Simona (2019). "L'onomastica nella ricostruzione del lessico: il caso di Retico ed Etrusco". Mélanges de l'École française de Rome - Antiquité (in Italian). Rome: École française de Rome. 131 (1). doi:10.4000/mefra.7613. ISBN 978-2-7283-1428-7. Retrieved January 31, 2020.

- Simona Marchesini (translation by Melanie Rockenhaus) (2013). "Rhaetic (languages)". Mnamon - Ancient Writing Systems in the Mediterranean. Scuola Normale Superiore. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Mellaart, James (1975), "The Neolithic of the Near East" (Thames and Hudson)

- Myres, JL (1907), "A history of the Pelasgian theory", Journal of Hellenic Studies, London : Published by the Council of the Society: 169–225,

s. 16 (Pelasgians and Tyrrhenians)

. - Strabo, Lacus Curtius (public domain translation), Jones, HL transl., U Chicago,

And again, Anticleides says that they (the Pelasgians) were the first to settle the regions round about Lemnos and Imbros, and indeed that some of these sailed away to Italy with Tyrrhenus the son of Atys

. - Herodotus, The Histories, Perseus, Tufts, 6, 137.

- De Ligt, Luuk. "An Eteocretan' inscription from Praisos and the homeland of the Sea Peoples" (PDF). talanta.nl. ALANTA XL-XLI (2008-2009), 151-172.

- Marchesini, Simona (2009). Le lingue frammentarie dell'Italia antica (in Italian). Milano: Hoepli Editore.

- Mellaart, James (1975), "The Neolithic of the Near East" (Thames and Hudson)

- Facchetti 2001.

- Facchetti 2002, p. 136.

- Steinbauer 1999.

- Palmer 1965.

- Penney, John H. W. (2009). "The Etruscan language and its Italic context". Etruscan by definition: the cultural, regional and personal identity of the Etruscans. Papers in honour of Sybille Haynes. London: British Museum Press. pp. 88–94.

These further Anatolian connections are not very convincing, though the relationship between Etruscan and Lemnian remains secure. Before concluding that this still makes an eastern origin for Etruscan most likely, a further language with Etruscan affinities must be noted. This is Raetic, a language attested in some 200 very short inscriptions from the Alpine region to the north of Verona. Despite their brevity, a number of linguistic patterns can be recognised which point to a relationship with Etruscan."(....) The correspondences (of Etruscan) with Raetic seem entirely convincing, but it is important to note that there are differences between the languages too (for instance, the patronymic suffixes are similar but not identical), so that Raetic cannot just be seen as a form of Etruscan. As in the case of Lemnian, we have related languages belonging to the same family, so should we suppose that Proto-Tyrrhenian may have extended rather widely in prehistoric times? Certainly the introduction of Raetic into the argument, with the ensuing geographical complications, makes the notion of a straightforward migration of Etruscans from Asia Minor seem a little too simple. And it is not in the end clear that we can be sure that the Etruscans did come from outside Italy, at least in any period of which we can hope to give a historical account, whatever the romantic attractions of scenarios such as displacement in the wake of the Trojan War.

- Starostin, Sergei; Orel, Vladimir (1989). "Etruscan and North Caucasian". In Shevoroshkin, Vitaliy (ed.). Explorations in Language Macrofamilies. Bochum Publications in Evolutionary Cultural Semiotics. Bochum.

Sources

- De Simone, Carlo (1996), I Tirreni a Lemnos. Evidenza linguistica e tradizioni storiche (in Italian), Florence: Olschki.

- Rix, Helmut (1998), Rätisch und Etruskisch [Raetian & Etruscan] (in German), Innsbruck.

- Schumacher, Stefan (1998), "Sprachliche Gemeinsamkeiten zwischen Rätisch und Etruskisch", Der Schlern (in German), 72: 90–114.

- Steinbauer, Dieter H (1999), Neues Handbuch des Etruskischen [New handbook on Etruscan] (in German), St. Katharinen.

- Facchetti, Giulio M (2001), "Qualche osservazione sulla lingua minoica" [Some observations on the Minoican language], Kadmos (in Italian), 40: 1–38, doi:10.1515/kadm.2001.40.1.1.

- Facchetti, Giulio M (2002), "Appendice sulla questione delle affinità genetiche dell'Etrusco" [Appendix on questions of the Etruscan genetic affinity], Appunti di Morfologia Etrusca (in Italian), Leo S. Olschki: 111–50, ISBN 978-88-222-5138-1.

- Schumacher, Stefan (2004), "Die rätischen Inschriften. Geschichte und heutiger Stand der Forschung. 2. erweiterte Auflage", Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft (in German), Innsbruck: Institut für Sprachen und Literaturen der Universität Innsbruck, 121 = Archaeolingua 2.

- Oettinger, Norbert (2010), "Seevölker und Etrusker", Pax Hethitica Studies on the Hittites and their Neighbours in Honour of Itamar Singer (in German), Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 233–246.

- De Simone, Carlo (2011), "La Nuova Iscrizione 'Tirsenica' di Lemnos (Efestia, teatro): considerazioni generali", Rasenna: Journal of the Center for Etruscan Studies (in Italian), Amherst: Classics Department and the Center for Etruscan Studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 1.

- De Simone, Carlo; Marchesini, Simona (2013), La lamina di Demlfeld (in Italian), Pisa-Roma: Fabrizio Serra Editore.