Mirndi languages

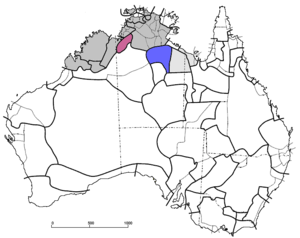

The Mirndi or Mindi languages are an Australian language family spoken in the Northern Territory of Australia. The family consists of two sub-groups, the Yirram languages and the Barkly languages some 200 km farther to the southeast, separated by the Ngumpin languages.[2][3] The primary difference between the two sub-groups is that while the Yirram languages are all prefixing like other non-Pama–Nyungan languages, the Barkly languages are all suffixing like most Pama–Nyungan languages.[4]

| Mirndi | |

|---|---|

| Mindi | |

| Geographic distribution | Victoria River and Barkly Tableland, Northern Territory |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | mirn1241[1] |

Yirram

Barkly (Jingulu + Ngurlun)

other non-Pama–Nyungan families | |

The name of the family is derived from the dual inclusive pronoun "we" which is shared by all the languages in the family in the form of either "mind-" or "mirnd-".[2]

Classification

The family has been generally accepted after being first established by Neil Chadwick in the early 1980s. The genetic relationship is primarily based upon morphology and not lexical comparison,[4] with the strongest evidence being found among the pronouns. However, "there are very few other systematic similarities in other areas of grammar[, which] throw some doubts on the Mirndi classification, making it less secure than generally accepted."[5] Nonetheless, as of 2008 proto-Mirndi has been reconstructed.[6]

| Mirndi |

| |||||||||||||||||||||

An additional language may be added, Ngaliwurru. However, it is unsure whether it is a language on its own, or merely a dialect of the Jaminjung language.[3][7][8][9][10] The same is true for Gudanji and Binbinka, although these are generally considered dialects of the Wambaya language. These three dialects are collectively referred to as the McArthur River languages.[4][9][11]

Vocabulary

Due to the close contact been the Yirram languages and the Barkly languages, and the Ngumpin languages and other languages as well, many of the cognates that the Yirram and Barkly languages share may in fact be loanwords, especially of Ngumpin origin.[2] For instance, while the Barkly language Jingulu only shares 9% of its vocabulary with its Yirram relative, the Ngaliwurru dialect of the Jaminjung language, it shares 28% with the nearby Ngumpin language Mudburra.[4]

Within the Barkly branch, the Jingulu language shares 29% and 28% of its vocabulary with its closest relatives, the Wambaya language and the Ngarnka language, respectively. The Ngarnka language shares 60% of its vocabulary with the Wambaya language, while the Wambaya language shares 69% and 78% with its dialects, Binbinka and Gudanji, respectively. Finally, these two dialects share 88% of their vocabulary.[11]

Proto-language

| Proto-Mirndi | |

|---|---|

| Reconstruction of | Mirndi languages |

Proto-Mirndi reconstructions by Harvey (2008):[6]

no. gloss Proto-Mirndi 1 to hang, to tip *jalalang 2 high, up *thangki 3 women's song style *jarra(r)ta 4 that (not previously mentioned) *jiyi 5 mother's father *jaju 6 woman's son *juka 7 bird (generic) *ju(r)lak 8 blind *kamamurri 9 daughter's child *kaminyjarr 10 cold *karrij 11 chickenhawk *karrkany 12 bull ant *(kija-)kija 13 to tickle *kiji-kiji(k) 14 red ochre *kitpu 15 shitwood *kulinyjirri 16 dove sp. *kuluku(ku) 17 sky *kulumarra 18 throat, didgeridoo *kulumpung 19 urine *kumpu 20 firestick *kungkala 21 pollen *kuntarri 22 flesh *kunyju 23 fat *kurij 24 bush turkey *kurrkapati 25 boomerang *kurrupartu 26 club *ku(r)turu 27 shield *kuwarri 28 fire *kuyVka 29 father-in-law *lamparra 30 car *langa 31 bony *larrkaja 32 plant sp. *lawa 33 eagle *lirraku 34 blue-tongue lizard *lungkura 35 to return *lurrpu 36 to wave *mamaj 37 ear *manka 38 plant sp. *manyanyi 39 gutta percha tree *manyingila 40 butterfly *marli-marli 41 old man *marluka 42 all right, later *marntaj 43 human status term *marntak 44 circumcision ritual *marntiwa 45 upper leg, thigh, root *mira 46 owl *mukmuk 47 to be dark *mu(wu)m 48 scorpion *muntarla 49 string *munungku 50 upper arm *murlku 51 three *murrkun 52 to name *nij 53 hand *nungkuru 54 female antilopine wallaroo *ngalijirri 55 to lick *ngalyak 56 to sing *nganya 57 bauhinia *ngapilipili 58 father's mother *ngapuju 59 breast *ngapulu 60 to be hot *ngartap 61 bird sp. *nyurijman 62 to dream *pank(iy)aja 63 older brother *papa 64 nightjar *parnangka 65 young woman *parnmarra 66 women's dance *pa(r)ntimi 67 moon *partangarra 68 baby *partarta 69 hot weather *parung(ku) 70 cicatrice *pa(r)turu 71 scraper *pin(y)mala 72 father *pipi 73 snake (generic) *pulany 74 to bathe *pulukaj(a) 75 ashes *puna 76 full *punturr/tu 77 to finish *purrp 78 dreaming *puwarraja 79 deep (hole) *tarlukurra 80 flame, light *tili/u 81 to be tied up *tirrk 82 feather *tiya-tiya 83 to poke *turrp 84 to open *walk 85 woomera *wa(r)lmayi 86 black-headed python *warlujapi 87 strange(r) *warnayaki 88 grass (generic) *warnta 89 to scratch *warr 90 number seven boomerang *warratirla 91 freshwater crocodile *warrija 92 to be together *warrp 93 parrot sp. *wilikpan 94 new *yalang 95 initiated youth *yapa 96 magic song *yarrinti 97 young man *yarrulan

References

Notes

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Mirndi". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Schultze-Berndt 2000, p. 8

- McConvell, Patrick (2009), "'Where the spear sticks up' – The variety of locatives in placenames in the Victoria River District, Northern Territory", in Koch, Harold; Hercus, Luise (eds.), Aboriginal Placenames: Naming and re-naming the Australian landscape, ANU E-Press, pp. 359–402, ISBN 978-1-921666-08-7

- Green, Ian (1995). "The death of 'prefixing': contact induced typological change in northern Australia". Berkeley Linguistics Society. 21: 414–425.

- Bowern, Claire; Koch, Harold (2004), Australian languages: Classification and the comparative method, John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 14–15, ISBN 978-1-58811-512-6

- Harvey, Mark (2008). Proto Mirndi: A discontinuous language family in Northern Australia. PL 593. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 978-0-85883-588-7.

- Pensalfini, Robert J. (2001), "On the Typological and Genetic Affiliation of Jingulu", in Simpson, Jane; Nash, David; Laughren, Mary; Austin, Peter; Alpher, Barry (eds.), Forty years on Ken Hale and Australian languages, Pacific Linguistics, pp. 385–399

- Schultze-Berndt 2000, p. 7

- Harvey, Mark; Nordlinger, Rachel; Green, Ian (2006). "From Prefixes to Suffixes: Typological Change in Northern Australia". Diachronica. 23 (2): 289–311. doi:10.1075/dia.23.2.04har.

- Schultz-Berndt, Eva F. (2002), "Constructions in Language Description", Functions of Language, 9 (2): 267–308

- Pensalfini, Robert J. (1997), Jingulu Grammar, Dictionary, and Texts, Massachusetts, United States: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, p. 19

12. Chadwick, Neil (1997) "The Barkly and Jaminjungan Languages: A Non-Contiguous Genetic Grouping In North Australia" in Tryon, Darrell, Walsh, Michael, eds. Boundary Rider: Essays in honour of Geoffrey O'Grady. Pacific Linguistics, C-136

General

| Wiktionary has a list of reconstructed forms at Appendix:Proto-Mirndi reconstructions |

- Schultze-Berndt, Eva F. (2000), Simple and Complex Verbs in Jaminjung – A Study of event categorisation in an Australian language