Eteocretan language

Eteocretan (/ˌiːtioʊˈkriːtən, ˌɛt-/ from Greek: Ἐτεόκρητες, translit. Eteókrētes, lit. "true Cretans", itself composed from ἐτεός eteós "true" and Κρής Krḗs "Cretan")[2] is the pre-Greek language attested in a few alphabetic inscriptions of ancient Crete.

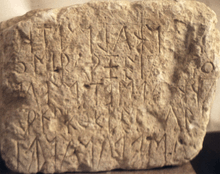

| Eteocretan | |

|---|---|

Eteocretan Inscription from Praisos | |

| Native to | Dreros, Praisos |

| Region | Crete |

| Era | late 7th–3rd century BC |

| Greek alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ecr |

ecr | |

| Glottolog | eteo1236[1] |

In eastern Crete about half a dozen inscriptions have been found which, though written in Greek alphabets, are clearly not Greek. These inscriptions date from the late 7th or early 6th century down to the 3rd century BC. The language, which so far cannot be translated, is probably a survival of a language spoken on Crete before the arrival of Greeks and is probably derived from the Minoan language preserved in the Linear A inscriptions of a millennium earlier. Since that language remains undeciphered, it is not certain that Eteocretan and Minoan are related, although this is very likely.

Ancient testimony suggests that the language is that of the Eteocretans, i.e. "true Cretans". The term Eteocretan is sometimes applied to the Minoan language (or languages) written more than a millennium earlier in so-called Cretan 'hieroglyphics' (almost certainly a syllabary) and in the Linear A script. Yves Duhoux, a leading authority on Eteocretan, has stated that "it is essential to rigorously separate the study of Eteocretan from that of the 'hieroglyphic' and Linear A inscriptions".[3]

Ancient Greek sources

Odysseus, after returning home and pretending to be a grandson of Minos, tells his wife Penelope about his alleged homeland of Crete:

Κρήτη τις γαῖ᾽ ἔστι μέσῳ ἐνὶ οἴνοπι πόντῳ, |

There is a land called Crete in the midst of the wine-dark sea, |

In the first century AD the geographer Strabo noted the following about the settlement of the different 'tribes' of Crete:

τούτων φησὶ Στάφυλος τὸ μὲν πρὸς ἔω Δοριεῖς κατέχειν, τὸ δὲ δυσμικόν Κύδωνας, τὸ δὲ νότιον Ἐτεόκρητας ὧν εἶναι πολίχνιον Πρᾶσον, ὅπου τὸ τοῦ Δικταίου Διὸς ἱερόν· τοὺς μὲν οὖν Ἐτεόκρητας καὶ Κύδωνας αὐτόχθονας ὑπάρξαι εἰκός, τοὺς δὲ λοιποὺς ἐπήλυδας, […] |

Of them [the peoples in the above passage] Staphylos says that the Dorians occupy the region towards the east, the Kydones the western part, the Eteocretans the southern, whose town is Prasos, where the temple of Diktaian Zeus is; and that the Eteocretans and Kydones are probably indigenous, but the others incomers, […][5] |

Indeed, more than half the known Eteocretan texts are from Praisos (Strabo's Πρᾶσος);[6] the others were found at Dreros (modern Driros).

Inscriptions

There are five inscriptions which are clearly Eteocretan, two of them bilingual with Greek. Three more fragments may be Eteocretan. The Eteocretan corpus is documented and discussed in Duhoux's L'Étéocrétois: les textes—la langue.[7]

Dreros

The two bilingual inscriptions, together with six other Greek inscriptions, were found in the western part of the large Hellenistic cistern next to the east wall of the Delphinion (temple of Apollo Delphinios) in Dreros, at a depth between three and four metres.[8] The texts are all written in the archaic Cretan alphabet and date from the late seventh or early sixth century BC. They record official religious and political decisions and probably came from the east wall of the Delphinion; they were published by Henri Van Effenterre in 1937 and 1946 and were kept in the museum at Neapolis.

The longer of these two inscriptions was found in the autumn of 1936 but not published until 1946.[9] The Greek part of the text is very worn and could not easily be read. Almost certainly with modern technology the Greek part would yield more but the inscription was lost during the occupation of the island in World War II. Despite searches over 70 years, it has not been found.

The other Dreros inscription was also published by Van Effenterre in 1946.[10] The Eteocretan part of the text has disappeared, only the fragment τυπρμηριηια (tuprmēriēia) remaining.

Praisos (or Praesos)

The other three certain Eteocretan inscriptions were published by Margherita Guarducci in the third volume of Inscriptiones Creticae, Tituli Cretae Orientalis, in 1942.[6] The inscriptions are archived in the Archeological Museum at Heraklion. Raymond A. Brown, who examined these inscriptions in the summer of 1976, has published them online with slightly different transcriptions than those given by Guarducci.

The earliest of these inscriptions is, like the Dreros one, written in the archaic Cretan alphabet and likewise dates from the late 7th or early 6th century BC. The second of the Praisos inscriptions is written in the standard Ionic alphabet, except for lambda which is still written in the archaic Cretan style; it probably dates from the 4th century BC.[11] The third inscription, dating probably from the 3rd century BC, is written in the standard Ionic alphabet with the addition of digamma or wau.

Other possible fragmentary inscriptions

Guarducci included three other fragmentary inscriptions;[6] two of these fragments were also discussed by Yves Duhoux.[12] The latter also discussed several other fragmentary inscriptions which might be Eteocretan.[13] All these inscriptions, however, are so very fragmentary that it really is not possible to state with any certainty that they may not be Greek.

A modern forgery

Older publications also list what was determined to be a modern forgery as an Eteocretan inscriptions.[14][15][16] It is variously known as the Psychro inscription or the Epioi inscription.

The inscription has five words, which bear no obvious resemblance to the language of the Dreros and Praisos inscriptions, apparently written in the Ionic alphabet of the third century BC, with the addition of three symbols which resemble the Linear A script of more than a millennium earlier. The enigmatic inscription has attracted the attention of many, but has been shown by Dr Ch. Kritzas to be a modern forgery.[17]

Description

The inscriptions are too few to give much information about the language.

Lexicon

The early inscriptions written in the archaic Cretan alphabet do mark word division; the same goes for the two longer inscriptions from the fourth and third centuries BC.

From the Dreros inscriptions are the following words: et isalabre komn men inai isaluria lmo tuprmēriēia. Komn and lmo seem to show that /n/ and /l/ could be syllabic. As to the meanings of the words, nothing can be said with any certainty. Van Effenterre suggested:

- inai = Dorian Cretan ἔϝαδε (= classical Greek ἅδε, third singular aorist of ἅνδάνω) "it pleased [the council, the people]", i. e. "it was decided [that …]".[9] The word ἔϝαδε occurs in the Greek part of the bilingual text, and all but one of the other Greek texts from the Delphinion in Dreros.

- tuprmēriēia = καθαρὸν γένοιτο in the Greek part of the inscription, i. e. "may it become pure".[10]

Also, Van Effenterree noted that the word τυρό(ν) ("cheese") seems to occur twice in the Greek part of the first Dreros bilingual and suggested the text concerned the offering of goat cheese to Leto, the mother goddess of the Delphinion triad and that the words isalabre and isaluria were related words with the meaning of "(goat) cheese".[9]

The only clearly complete word on the earliest Praisos inscription is barze, and there is no indication of its meaning.

The other two Praisos inscriptions do not show word breaks. It has, however, been noted that in the second line of the fourth century inscription is phraisoi inai (φραισοι ιναι), and it has been suggested that it means "it pleased the Praisians" (ἔϝαδε Πραισίοις).[9]

Classification

Though meager, the inscriptions show a language that bears no obvious kinship to Indo-European or Semitic languages; the language appears to be unrelated to Etruscan or any other known ancient language of the Aegean or Asia Minor. Raymond A. Brown, after listing a number of words of pre-Greek origin from Crete suggests a relation between Eteocretan, Lemnian (Pelasgian), Minoan, and Tyrrhenian, coining the name "Aegeo-Asianic" for the proposed language family.[18] In whichever case, unless further inscriptions, especially bilingual ones, are found, the Eteocretan language must remain 'unclassified.'

While Eteocretan is possibly descended from the Minoan language of Linear A inscriptions of a millennium earlier, until there is an accepted decipherment of Linear A, that language must also remain unclassified and the question of a relationship between the two remains speculative, especially as there seem to have been other non-Greek languages spoken in Crete.[19]

See also

Literature

- Raymond A. Brown, "The Eteocretan Inscription from Psychro," in Kadmos, vol. 17, issue 1 (1978), p. 43 ff.

- Raymond A. Brown, Pre-Greek Speech on Crete. Adolf M. Hakkert, Amsterdam 1984.

- Henri Van Effenterre in Bulletin de correspondance hellénique, vol. 70 (1946), p. 602 f.

- Henri Van Effenterre in Revue de Philologie, third series, vol. 20, issue 2 (1946), pp. 131–138.

- Margarita Guarducci: Inscriptiones Creticae, vol. 3. Rome 1942, pp. 134–142.

- Yves Duhoux: L'Étéocrétois: les textes – la langue. J. C. Gieben, Amsterdam 1982. ISBN 90 70265 05 2.

References

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Eteocretan". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- "Eteocretan". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Yves Duhoux: L'Étéocrétois: les textes – la langue. J. C. Gieben, Amsterdam 1982, p. 8.

- Homer, Odyssey 19, lines 172–177.

- Strabo, Geographika 10, 475.

- Margarita Guarducci: Inscriptiones Creticae, vol. 3. Rome 1942, pp. 134–142.

- Yves Duhoux: L'Étéocrétois: les textes – la langue. J. C. Gieben, Amsterdam 1982.

- Y. Duhoux, op. cit., pp. 27–53.

- Henri Van Effenterre in Revue de Philologie, third series, vol. 20, issue 2 (1946), pp. 131–138.

- Henri Van Effenterre in Bulletin de correspondance hellénique, vol. 70 (1946), p. 602 f.

- Y. Duhoux, op. cit., pp. 55–79.

- Y. Duhoux, op. cit., pp. 80–85.

- Y. Duhoux, op. cit., pp. 87–124.

- Spyridon Marinatos, "Γραμμάτων διδασκάλια", in Minoica: Festschrift zum 80. Geburstag von Johannes Sundwall, Berlin 1958, p. 227.

- Raymond A. Brown, "The Eteocretan Inscription from Psychro," in Kadmos, vol. 17, issue 1 (1978), p. 43 ff.

- Y. Duhoux, op. cit., pp. 87–111.

- Ch. B. Kritzas, The "Bilingual" inscription from Psychro (Crete). A coup de grâce, in R. Gigli (ed.), Μεγάλαι Νῆσοι. Studi dedicati a Giovanni Rizza per il suo ottantesimo compleanno, vol. 1. Catania 2004 [in fact, published in May 2006], pp. 255–261.

- Raymond A. Brown, Pre-Greek Speech on Crete. Adolf M. Hakkert, Amsterdam 1984, p. 289

- Y. Duhoux, op. cit., p. 8.