Jirajaran languages

The Jirajaran languages are group of extinct languages once spoken in western Venezuela in the regions of Falcón and Lara. All of the Jirajaran languages appear to have become extinct in the early 20th century.[2]

| Jirajaran | |

|---|---|

| Hiraháran | |

| Geographic distribution | Western Venezuela |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's primary language families |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | jira1235[1] |

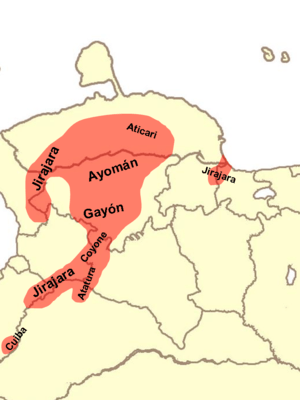

Pre-contact distribution of the Jirajaran languages | |

Languages

Based on adequate documentation, three languages are definitively classified as belonging to the Jirajaran family:[2]

- Jirajara, spoken in the state of Falcón

- Ayomán, spoken in the village of Siquisique in the state of Lara

- Gayón, spoken at the sources of the Tocuyo River in the state of Lara

Loukotka includes four additional languages, for which no linguistic documentation exists:[3]

- Coyone, spoken at the sources of the Portuguesa River in the state of Portuguesa

- Cuiba, spoken near the city of Aricagua

- Atatura, spoken between the Rocono and Tucupido rivers

- Aticari, spoken along the Tocuyo River

- Gayón (Cayon)

- Ayomán

- Xagua

- Cuiba (?)

- Jirajara

Classification

The Jirajaran languages are generally regarded as isolates. Adelaar and Muysken note certain lexical similarities with the Timotean languages and typological similarity to the Chibchan languages, but state that the data is too limited to make a definitive classification.[2] Jahn, among others, has suggested a relation between the Jirajaran language and the Betoi languages, mostly on the basis of similar ethnonyms.[5] Greenberg and Ruhlen classify Jirajaran as belonging to the Paezan language family, along with the Betoi languages, the Páez language, the Barbacoan languages and others.[6]

Language contact

Jolkesky (2016) notes that there are lexical similarities with the Sape, Timote-Kuika, and Puinave-Kak language families due to contact.[7]

Typology

Based on the little documentation that exists, a number of typological characteristics are reconstructable:[8]

- 1. VO word order in transitive clauses

- apasi mamán (Jirajara)

- I.cut my.hand

- I cut my hand

- 2. Subjects precede verbs

- depamilia buratá (Ayamán)

- the.family is.good

- The family is good

- 3. Possessors which precede the possessed

- shpashiú yemún (Ayamán)

- arc its.rope

- the arc of the rope

- 4. Adjectives follow the nouns they modify

- pok diú (Jirajara)

- hill big

- big hill

- 5. Numerals precede the nouns they quantify

- boque soó (Ayamán)

- one cigarette

- one cigarette

- 6. Use of postpositions, rather than prepositions

- angüi fru-ye (Jirajara)

- I.go Siquisique-to

- I go to Siquisique.

Vocabulary comparison

Jahn (1927) lists the following basic vocabulary items.[5]

Comparison of Jirajaran vocabulary, based on Jahn (1927) English Ayomán Gayón Jirajara fire dug dut, idú dueg foot a-sengán segué angán hen degaró digaró degaró house gagap hiyás gagap snake huhí, jují jují túb sun iñ yivat yuaú

Loukotka (1968) lists the following basic vocabulary items.[3]

Comparison of Jirajaran vocabulary, based on Loukotka (1968) gloss Jirajara Ayomán Gayón one bógha two auyí three mongañá head a-ktegi a-tógh is-tóz ear a-uñán a-kivóugh himigui tooth a-king man iyít yúsh yus water ing ing guayí fire dueg dug dut sun yuaú iñ yivat maize dos dosh dosivot bird chiskua chiskua house gagap gagap hiyás

Further reading

- Oramas, L. (1916). Materiales para el estudio de los dialectos Ayamán, Gayón, Jirajara, Ajagua. Caracas: Litografía del Comercio.

- Querales, R. (2008). El Ayamán. Ensayo de reconstrucción de un idioma indígena venezolano. Barquisimeto: Concejo Municipal de Iribarren.

References

| Wiktionary has word lists at Appendix:Jirajaran word lists |

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Jirajaran". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Adelaar, Willem F. H.; Pieter C. Muysken (2004). The Languages of the Andes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–30. ISBN 0-521-36275-X.

- Loukotka, Čestmír (1968). Classification of South American Indian Languages. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center. pp. 254–5.

- Mason, John Alden (1950). "The languages of South America". In Steward, Julian (ed.). Handbook of South American Indians. 6. Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office: Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 143. pp. 157–317.

- Jahn, Alfredo (1973) [1927]. Los Aborígenes del Occidente de Venezuela (in Spanish). Caracas: Monte Avila Editores, C.A.

- Greenberg, Joseph; Ruhlen, Merritt (2007-09-04). "An Amerind Etymological Dictionary" (PDF) (12 ed.). Stanford: Dept. of Anthropological Sciences Stanford University. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2010-12-25. Retrieved 2008-06-27. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Jolkesky, Marcelo Pinho de Valhery (2016). Estudo arqueo-ecolinguístico das terras tropicais sul-americanas (Ph.D. dissertation) (2 ed.). Brasília: University of Brasília.

- Costenla Umaña, Adolfo (May 1991). Las Lenguas del Área Intermedia: Introducción a su Estudio Areal (in Spanish). San José: Editorial de la Universidad de Costa Rica. pp. 56–8. ISBN 9977-67-158-3.