Abun language

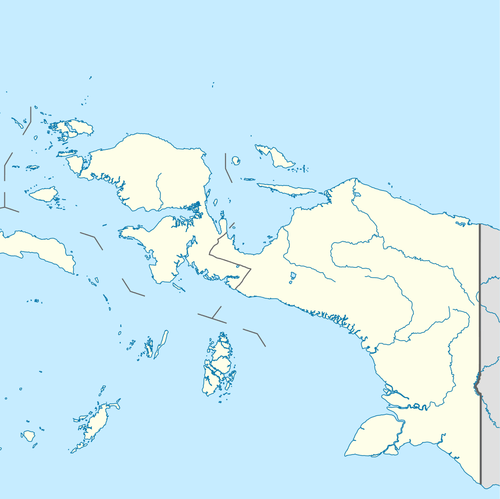

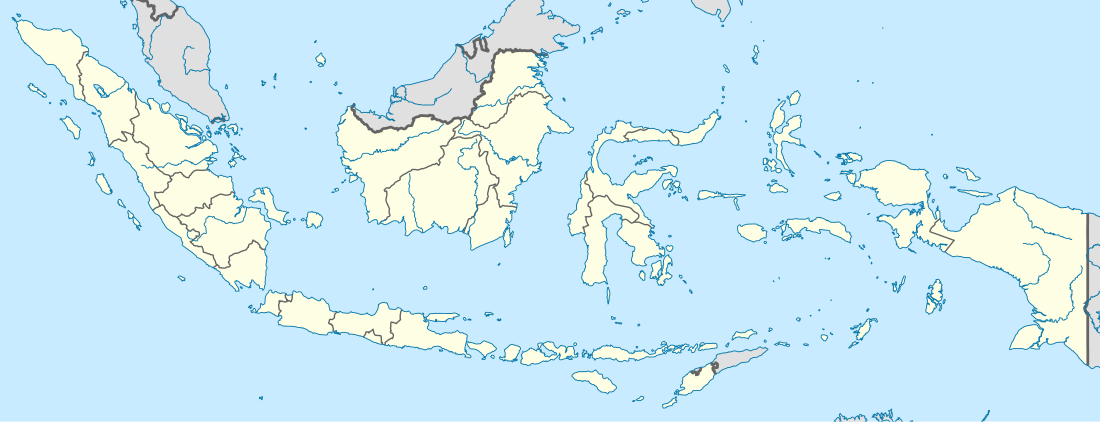

Abun, also known as Yimbun, Anden, Manif, or Karon, is a Papuan language spoken along the northern coast of the Bird's Head Peninsula in Abun District, Tambrauw Regency. It is not closely related to any other language, and though Ross (2005) assigned it to the West Papuan family, based on similarities in pronouns,[3] Palmer (2018), Ethnologue, and Glottolog list it as a language isolate.[1][2][4]

| Abun | |

|---|---|

| Native to | West Papua |

| Region | Tambrauw Regency, Bird's Head Peninsula: Ayamaru, Moraid, and Sausapor sub-districts - about 20 villages |

Native speakers | (3,000 cited 1995)[1] |

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | kgr |

| Glottolog | abun1252[2] |

Abun  Abun | |

| Coordinates: 0.57°S 132.42°E | |

Abun used to have three lexical tones, but only two are distinguished now as minimal pairs and even these are found in limited vocabulary. Therefore, Abun is said to be losing its tonality due to linguistic change.[5]

Being spoken along the coast of northwestern New Guinea, Abun is in contact with Austronesian languages; maritime vocabulary in Abun has been borrowed from Biak.[6]

Setting and dialects

The speakers number about 3,000 spread across 18 villages and several isolated hamlets. The Abun area occupies a stretch of the northern coast of the Bird's Head Peninsula. The neighbouring languages are: Moi to the southwest along the coast, Moraid and Karon Dori to the south (the latter is a dialect of Maybrat), and Mpur to the east.[7]

The Abun speakers refer to their language as either Abun or Anden. Several other names are in use by neighbouring groups: the Moi call it Madik, the Mpur refer to it as Yimbun or Yembun, while among the Biak people it is known as Karon Pantai, a term with derogatory connotations.[8]

Abun has four distinct dialects: Abun Tat, Abun Ye, and the two dialects of Abun Ji. The two Abun Ji dialects are differentiated by their use of /r/ or /l/. Abun exists on a dialect continuum from Abun Tat to Abun Ji /l/: speakers of Abun Tat are less able to understand Abun Ji than Abun Ye.[9]

Phonology

Abun has 5 vowels: /a, e, i, o, u/.[9]

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Postalveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | voiceless | p | t | k | |||

| voiced | b | d | g | ||||

| prenasal. | mb | nd | ŋg | ||||

| Affricate | voiced | d͡ʒ | |||||

| prenasal. | nd͡ʒ | ||||||

| Fricative | f | s | ʃ | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||||

| Approximant | l | j | w | ||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

Tones

Abun has three lexical tones, which are high, mid, and low. A minimal set showing all three tones:[6]

(1)

ʃúr ʃè water flow - ‘the water flows’

(2)

ʃúr ʃé water flood - ‘a big flood’

(3)

ʃúr ʃe water big - ‘a big river’

High/rising tones can also be used to mark plurals (Berry & Berry 1999:21).

- ndam ‘bird’, ndám ‘birds’

- nu ‘house’, nú ‘houses’

- gwa ‘taro tuber’, gwá ‘taro tubers’

Grammar

Abun has bipartite negation like French, using the pre-predicate negator yo and post-predicate negator nde. Both are obligatory.[6]:608–609 Example:

Án yo ma mo nu nde. wood NEG come to house NEG - ‘They didn’t come to the house.’

Like the other language isolates of the northern Bird's Head Peninsula, Abun is a heavily isolating language, with many one-to-one word-morpheme correspondences, as shown in the example sentence below.[6]

Men ben suk mo nggwe yo, men ben suk sino. 1PL do thing LOC garden then 1PL do thing together - ‘If we do things at the garden, then we do them together.’

References

- Abun at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Abun". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

-

- Ross, Malcolm (2005). "Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages". In Andrew Pawley; Robert Attenborough; Robin Hide; Jack Golson (eds.). Papuan pasts: cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 15–66. ISBN 0858835622. OCLC 67292782.

- Palmer, Bill (2018). "Language families of the New Guinea Area". In Palmer, Bill (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide. The World of Linguistics. 4. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 1–20. ISBN 978-3-11-028642-7.

- Muysken, Pieter. From Linguistic Areas to Areal Linguistics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 134. ISBN 9789027231000.

- Holton, Gary; Klamer, Marian (2018). "The Papuan languages of East Nusantara and the Bird's Head". In Palmer, Bill (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide. The World of Linguistics. 4. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 569–640. ISBN 978-3-11-028642-7.

- Berry & Berry 1999, p. 1.

- Berry & Berry 1999, p. 2.

- Berry & Berry 1999.

Sources

- Berry, Christine; Berry, Keith (1999). A description of Abun: a west Papuan language of Irian Jaya (PDF). Pacific Linguistics Series B, Volume 115. Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. ISBN 0 85883 482 0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)