Hindi

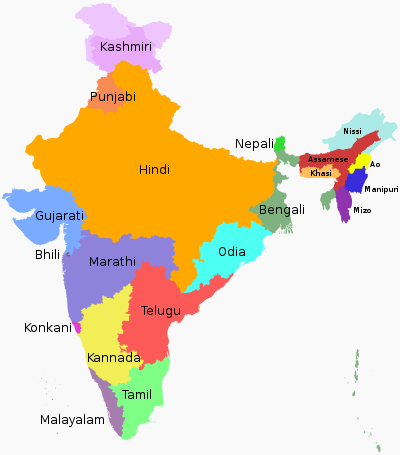

Hindi (Devanagari: हिन्दी, IAST/ISO 15919: Hindī), or more precisely Modern Standard Hindi (Devanagari: मानक हिन्दी, IAST/ISO 15919: Mānak Hindī),[6] is an Indo-Aryan language spoken in India. Hindi is often described as a standardised and Sanskritised register[7] of the Hindustani language, which itself is based primarily on the Khariboli dialect of Delhi and neighbouring areas of Northern India.[8][9][10] Hindi, written in the Devanagari script, is one of the two official languages of the Government of India, along with the English language.[11] It is an official language of 9 states and 3 Union Territories and additional official language of 3 states.[12][13][14][15] It is one of the 22 scheduled languages of the Republic of India.[16]

| Hindi | |

|---|---|

| Modern Standard Hindi | |

| हिंदी Hindī | |

The word "Hindi" in Devanagari script | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈɦɪndiː] |

| Native to | India |

| Region | Northern, Eastern, Western and Central India (Hindi Belt) |

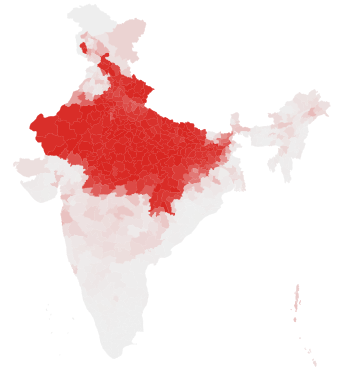

Native speakers | L1 speakers: 322 million speakers of Hindi and various related languages reported their language as 'Hindi' (2011 census)[1] L2 speakers: 270 million (2016)[2] |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Vedic Sanskrit

|

| Dialects |

|

| |

| Signed Hindi | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Central Hindi Directorate[4] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | hi |

| ISO 639-2 | hin |

| ISO 639-3 | hin |

hin-hin | |

| Glottolog | hind1269[5] |

| Linguasphere | 59-AAF-qf |

| |

Hindi is the lingua franca of the Hindi belt and to a lesser extent other parts of India (usually in a simplified or pidginised variety such as Bazaar Hindustani or Haflong Hindi).[12][17] Outside India, several other languages are recognised officially as "Hindi" but do not refer to the Standard Hindi language described here and instead descend from other dialects, such as Awadhi and Bhojpuri. Such languages include Fiji Hindi, which is official in Fiji,[18] and Caribbean Hindustani, which is spoken in Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Suriname.[19][20][21][22] Apart from the script and formal vocabulary, standard Hindi is mutually intelligible with standard Urdu, another recognised register of Hindustani as both share a common colloquial base.[23]

As a linguistic variety, Hindi is the fourth most-spoken first language in the world, after Mandarin, Spanish and English.[24] Hindi alongside Urdu as Hindustani is the third most-spoken language in the world, after Mandarin and English.[25][26]

Etymology

The term Hindī originally was used to refer to inhabitants of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It was borrowed from Classical Persian هندی Hindī (Iranian Persian pronunciation: Hendi), meaning "of or belonging to Hind (India)" (hence, "Indian").[27]

Another name Hindavī (हिंदवी) or Hinduī (हिंदुई) (from Persian: هندوی "of or belonging to the Hindu/Indian people") was often used in the past, for example by Amir Khusrow in his poetry.[28][29]

The terms "Hindi" and "Hindu" trace back to Old Persian which derived these names from the Sanskrit name Sindhu (सिन्धु ), referring to the river Indus. The Greek cognates of the same terms are "Indus" (for the river) and "India" (for the land of the river).[30][31]

History

Like other Indo-Aryan languages, Hindi is a direct descendant of an early form of Vedic Sanskrit, through Sauraseni Prakrit and Śauraseni Apabhraṃśa (from Sanskrit apabhraṃśa "corrupt"), which emerged in the 7th century CE.[32] After the arrival of Islamic administrative rule in northern India, Old Hindi acquired many loanwords from Persian, as well as Arabic,[33] which led to the development of Hindustani. In the 18th century, an intensively Persianised version of Hindustani emerged and came to be called Urdu.[34][35][36] The growing importance of Hindustani in colonial India and the association of Urdu with Muslims prompted Hindus to develop a Sanskritised version of Hindustani, leading to the formation of Modern Standard Hindi a century after the creation of Urdu.[37][38]

Before the standardisation of Hindi on the Delhi dialect, various dialects and languages of the Hindi belt attained prominence through literary standardisation, such as Avadhi and Braj Bhasha. Early Hindi literature came about in the 12th and 13th centuries CE. This body of work included the early epics such as renditions of the Dhola Maru in the Marwari of Marwar,[39] the Prithviraj Raso in the Braj Bhasha of Braj, and the works of Amir Khusrow in the dialect of Delhi.[40][41]

Modern Standard Hindi is based on the Delhi dialect,[32] the vernacular of Delhi and the surrounding region, which came to replace earlier prestige dialects such as Awadhi, Maithili (sometimes regarded as separate from the Hindi dialect continuum) and Braj. Urdu – considered another form of Hindustani – acquired linguistic prestige in the latter part of the Mughal period (1800s), and underwent significant Persian influence. Modern Hindi and its literary tradition evolved towards the end of the 18th century.[42] John Gilchrist was principally known for his study of the Hindustani language, which was adopted as the lingua franca of northern India (including what is now present-day Pakistan) by British colonists and indigenous people. He compiled and authored An English-Hindustani Dictionary, A Grammar of the Hindoostanee Language, The Oriental Linguist, and many more. His lexicon of Hindustani was published in the Perso-Arabic script, Nāgarī script, and in Roman transliteration. He is also known for his role in the foundation of University College London and for endowing the Gilchrist Educational Trust. In the late 19th century, a movement to further develop Hindi as a standardised form of Hindustani separate from Urdu took form.[43] In 1881, Bihar accepted Hindi as its sole official language, replacing Urdu, and thus became the first state of India to adopt Hindi.[44]

After independence, the government of India instituted the following conventions:

- standardisation of grammar: In 1954, the Government of India set up a committee to prepare a grammar of Hindi; The committee's report was released in 1958 as A Basic Grammar of Modern Hindi.

- standardisation of the orthography, using the Devanagari script, by the Central Hindi Directorate of the Ministry of Education and Culture to bring about uniformity in writing, to improve the shape of some Devanagari characters, and introducing diacritics to express sounds from other languages.

On 14 September 1949, the Constituent Assembly of India adopted Hindi written in the Devanagari script as the official language of the Republic of India replacing Urdu's previous usage in British India.[45][46][47] To this end, several stalwarts rallied and lobbied pan-India in favour of Hindi, most notably Beohar Rajendra Simha along with Hazari Prasad Dwivedi, Kaka Kalelkar, Maithili Sharan Gupt and Seth Govind Das who even debated in Parliament on this issue. As such, on the 50th birthday of Beohar Rajendra Simha on 14 September 1949, the efforts came to fruition following the adoption of Hindi as the official language.[48] Now, it is celebrated as Hindi Day.[49]

Official status

India

Part XVII of the Indian Constitution deals with the official language of the Indian Commonwealth. Under Article 343, the official languages of the Union has been prescribed, which includes Hindi in Devanagari script and English:

(1) The official language of the Union shall be Hindi in Devanagari script. The form of numerals to be used for the official purposes of the Union shall be the international form of Indian numerals.[19]

(2) Notwithstanding anything in clause (1), for a period of fifteen years from the commencement of this Constitution, the English language shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union for which it was being used immediately before such commencement: Provided that the President may, during the said period, by order authorise the use of the Hindi language in addition to the English language and of the Devanagari form of numerals in addition to the international form of Indian numerals for any of the official purposes of the Union.[50]

Article 351 of the Indian constitution states

It shall be the duty of the Union to promote the spread of the Hindi language, to develop it so that it may serve as a medium of expression for all the elements of the composite culture of India and to secure its enrichment by assimilating without interfering with its genius, the forms, style and expressions used in Hindustani and in the other languages of India specified in the Eighth Schedule, and by drawing, wherever necessary or desirable, for its vocabulary, primarily on Sanskrit and secondarily on other languages.

It was envisioned that Hindi would become the sole working language of the Union Government by 1965 (per directives in Article 344 (2) and Article 351),[51] with state governments being free to function in the language of their own choice. However, widespread resistance to the imposition of Hindi on non-native speakers, especially in South India (such as the those in Tamil Nadu) led to the passage of the Official Languages Act of 1963, which provided for the continued use of English indefinitely for all official purposes, although the constitutional directive for the Union Government to encourage the spread of Hindi was retained and has strongly influenced its policies.[52]

Article 344 (2b) stipulates that official language commission shall be constituted every ten years to recommend steps for progressive use of Hindi language and imposing restrictions on the use of the English language by the union government. In practice, the official language commissions are constantly endeavouring to promote Hindi but not imposing restrictions on English in official use by the union government.

At the state level, Hindi is the official language of the following Indian states: Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Mizoram, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand.[53] It is one of the additional official languages of West Bengal.[54][55][56] Each may also designate a "co-official language"; in Uttar Pradesh, for instance, depending on the political formation in power, this language is generally Urdu. Similarly, Hindi is accorded the status of official language in the following Union Territories: National Capital Territory, Andaman and Nicobar Islands and Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu.

National language status for Hindi is a long-debated theme.[57] In 2010, the Gujarat High Court clarified that Hindi is not the national language of India because the constitution does not mention it as such.[58][59][60]

Nepal

Hindi is spoken as a first language by about 77,569 people in Nepal according to the 2011 Nepal census, and further by 1,225,950 people as a second language.[61]

Fiji

Outside Asia, the Awadhi language (an Eastern Hindi dialect) with influence from Bhojpuri, Bihari languages, Fijian and English is spoken in Fiji.[62][63] It is an official language in Fiji as per the 1997 Constitution of Fiji,[64] where it referred to it as "Hindustani", however in the 2013 Constitution of Fiji, it is simply called "Fiji Hindi".[65] It is spoken by 380,000 people in Fiji.[62]

Geographical distribution

Hindi is the lingua franca of northern India (which contains the Hindi Belt), as well as an official language of the Government of India, along with English.[50]

In Northeast India a pidgin known as Haflong Hindi has developed as a lingua franca for the people living in Haflong, Assam who speak other languages natively.[66] In Arunachal Pradesh, Hindi emerged as a lingua franca among locals who speak over 50 dialects natively.[67]

Hindi is quite easy to understand for many Pakistanis, who speak Urdu, which, like Hindi, is a standard register of the Hindustani language; additionally, the Indian media is widely viewed in Pakistan.[68]

A sizeable population in Afghanistan, especially in Kabul, can also speak and understand Hindi-Urdu due to the popularity and influence of Bollywood films, songs and actors in the region.[69][70]

Hindi is also spoken by a large population of Madheshis (people having roots in north-India but have migrated to Nepal over hundreds of years) of Nepal. Apart from this, Hindi is spoken by the large Indian diaspora which hails from, or has its origin from the "Hindi Belt" of India. A substantially large North Indian diaspora lives in countries like the United States of America, the United Kingdom, the United Arab Emirates, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Suriname, South Africa, Fiji and Mauritius, where it is natively spoken at home and among their own Hindustani-speaking communities. Outside India, Hindi speakers are 8 million in Nepal; 863,077 in United States of America;[71][72] 450,170 in Mauritius; 380,000 in Fiji;[62] 250,292 in South Africa; 150,000 in Suriname;[73] 100,000 in Uganda; 45,800 in United Kingdom;[74] 20,000 in New Zealand; 20,000 in Germany; 26,000 in Trinidad and Tobago;[73] 3,000 in Singapore.

Comparison with Modern Standard Urdu

Linguistically, Hindi and Urdu are two registers of the same language and are mutually intelligible.[75] Hindi is written in the Devanagari script and contains more Sanskrit-derived words than Urdu, whereas Urdu is written in the Perso-Arabic script and uses more Arabic and Persian loanwords than does Hindi. However, both share a core vocabulary of native Prakrit and Sanskrit-derived words,[23][76][77] with large numbers of Arabic and Persian loanwords.[33] Because of this, as well as the fact that the two registers share an identical grammar,[10][23][76] a consensus of linguists consider them to be two standardised forms of the same language, Hindustani or Hindi-Urdu.[75][10][23][9] Hindi is the most commonly used official language in India. Urdu is the national language and lingua franca of Pakistan and is one of 22 official languages of India, also having official status in Uttar Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, and Delhi.

The comparison of Hindi and Urdu as separate languages is largely motivated by politics, namely the Indo-Pakistani rivalry.[78]

Script

Hindi is written in the Devanagari script, an abugida. Devanagari consists of 11 vowels and 33 consonants and is written from left to right. Unlike for Sanskrit, Devanagari is not entirely phonetic for Hindi, especially failing to mark schwa dropping in spoken Standard Hindi.[79]

Romanization

The Government of India uses Hunterian transliteration as its official system of writing Hindi in the Latin script. Various other systems also exist, such as IAST, ITRANS and ISO 15919.

Vocabulary

Traditionally, Hindi words are divided into five principal categories according to their etymology:

- Tatsam (तत्सम "same as that") words: These are words which are spelled the same in Hindi as in Sanskrit (except for the absence of final case inflections).[80] They include words inherited from Sanskrit via Prakrit which have survived without modification (e.g. Hindi नाम nām / Sanskrit नाम nāma, "name"; Hindi कर्म karm / Sanskrit कर्म karma, "deed, action; karma"),[81] as well as forms borrowed directly from Sanskrit in more modern times (e.g. प्रार्थना prārthanā, "prayer").[82] Pronunciation, however, conforms to Hindi norms and may differ from that of classical Sanskrit. Amongst nouns, the tatsam word could be the Sanskrit non-inflected word-stem, or it could be the nominative singular form in the Sanskrit nominal declension.

- Ardhatatsam (अर्धतत्सम "semi-tatsama") words: Such words are typically earlier loanwords from Sanskrit which have undergone sound changes subsequent to being borrowed. (e.g. Hindi सूरज sūraj from Sanskrit सूर्य sūrya)

- Tadbhav (तद्भव "born of that") words: These are native Hindi words derived from Sanskrit after undergoing phonological rules (e.g. Sanskrit कर्म karma, "deed" becomes Sauraseni Prakrit कम्म kamma, and eventually Hindi काम kām, "work") and are spelled differently from Sanskrit.[80]

- Deshaj (देशज) words: These are words that were not borrowings but do not derive from attested Indo-Aryan words either. Belonging to this category are onomatopoetic words or ones borrowed from local non-Indo-Aryan languages.

- Videshī (विदेशी "foreign") words: These include all loanwords from non-indigenous languages. The most frequent source languages in this category are Persian, Arabic, English and Portuguese. Examples are क़िला qila "fort" from Persian, कमेटी kameṭī from English committee and साबुन sābun "soap" from Arabic.

Hindi also makes extensive use of loan translation (calqueing) and occasionally phono-semantic matching of English.[83]

Prakrit

Hindi has naturally inherited a large portion of its vocabulary from Śaurasenī Prākṛt, in the form of tadbhava words. This process usually involves compensatory lengthening of vowels preceding consonant clusters in Prakrit, e.g. Sanskrit tīkṣṇa > Prakrit tikkha > Hindi tīkhā.

Sanskrit

Much of Modern Standard Hindi's vocabulary is borrowed from Sanskrit as tatsam borrowings, especially in technical and academic fields. The formal Hindi standard, from which much of the Persian, Arabic and English vocabulary has been replaced by neologisms compounding tatsam words, is called Śuddh Hindi (pure Hindi), and is viewed as a more prestigious dialect over other more colloquial forms of Hindi.

Excessive use of tatsam words sometimes creates problems for native speakers. They may have Sanskrit consonant clusters which do not exist in native Hindi, causing difficulties in pronunciation.[84]

As a part of the process of Sanskritization, new words are coined using Sanskrit components to be used as replacements for supposedly foreign vocabulary. Usually these neologisms are calques of English words already adopted into spoken Hindi. Some terms such as dūrbhāṣ "telephone", literally "far-speech" and dūrdarśan "television", literally "far-sight" have even gained some currency in formal Hindi in the place of the English borrowings (ṭeli)fon and ṭīvī.[85]

Persian

Hindi also features significant Persian influence, standardised from spoken Hindustani.[33][86] Early borrowings, beginning in the mid-12th century, were specific to Islam (e.g. Muhammad, islām) and so Persian was simply an intermediary for Arabic. Later, under the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire, Persian became the primary administrative language in the Hindi heartland. Persian borrowings reached a heyday in the 17th century, pervading all aspects of life. Even grammatical constructs, namely the izafat, were assimilated into Hindi.[87]

Post-Partition the Indian government advocated for a policy of Sanskritization leading to a marginalisation of the Persian element in Hindi. However, many Persian words (e.g. muśkil "difficult", bas "enough", havā "air", x(a)yāl "thought") have remained entrenched in Modern Standard Hindi, and a larger amount are still used in Urdu poetry written in the Devanagari script.

Media

Literature

Hindi literature is broadly divided into four prominent forms or styles, being Bhakti (devotional – Kabir, Raskhan); Śṛṇgār (beauty – Keshav, Bihari); Vīgāthā (epic); and Ādhunik (modern).

Medieval Hindi literature is marked by the influence of Bhakti movement and the composition of long, epic poems. It was primarily written in other varieties of Hindi, particularly Avadhi and Braj Bhasha, but to a degree also in Delhavi, the basis for Modern Standard Hindi. During the British Raj, Hindustani became the prestige dialect.

Chandrakanta, written by Devaki Nandan Khatri in 1888, is considered the first authentic work of prose in modern Hindi.[89] The person who brought realism in the Hindi prose literature was Munshi Premchand, who is considered as the most revered figure in the world of Hindi fiction and progressive movement. Literary, or Sāhityik, Hindi was popularised by the writings of Swami Dayananda Saraswati, Bhartendu Harishchandra and others. The rising numbers of newspapers and magazines made Hindustani popular with the educated people.

The Dvivedī Yug ("Age of Dwivedi") in Hindi literature lasted from 1900 to 1918. It is named after Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi, who played a major role in establishing Modern Standard Hindi in poetry and broadening the acceptable subjects of Hindi poetry from the traditional ones of religion and romantic love.

In the 20th century, Hindi literature saw a romantic upsurge. This is known as Chāyāvād (shadow-ism) and the literary figures belonging to this school are known as Chāyāvādī. Jaishankar Prasad, Suryakant Tripathi 'Nirala', Mahadevi Varma and Sumitranandan Pant, are the four major Chāyāvādī poets.

Uttar Ādhunik is the post-modernist period of Hindi literature, marked by a questioning of early trends that copied the West as well as the excessive ornamentation of the Chāyāvādī movement, and by a return to simple language and natural themes.

Internet

Hindi literature, music, and film have all been disseminated via the internet. In 2015, Google reported a 94% increase in Hindi-content consumption year-on-year, adding that 21% of users in India prefer content in Hindi.[90] Many Hindi newspapers also offer digital editions.

Sample text

The following is a sample text in High Hindi, of the Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (by the United Nations):

- Hindi

- अनुच्छेद 1 (एक) – सभी मनुष्यों को गौरव और अधिकारों के विषय में जन्मजात स्वतन्त्रता और समानता प्राप्त हैं। उन्हें बुद्धि और अन्तरात्मा की देन प्राप्त है और परस्पर उन्हें भाईचारे के भाव से बर्ताव करना चाहिए।

- Transliteration (IAST)

- Anucched 1 (ek) – Sabhī manuṣyõ ko gaurav aur adhikārõ ke viṣay mẽ janmajāt svatantratā aur samāntā prāpt hai. Unhẽ buddhi aur antarātmā kī den prāpt hai aur paraspar unhẽ bhāīcāre ke bhāv se bartāv karnā cāhie.

- Transcription (IPA)

- [ənʊtʃʰːeːd eːk | səbʱiː mənʊʃjõː koː ɡɔːɾəʋ ɔːr ədʱɪkaːɾõ keː maːmleː mẽː dʒənmədʒaːt sʋətəntɾətaː ɔːr səmaːntaː pɾaːpt hɛː ‖ ʊnʱẽ bʊdʱːɪ ɔːɾ əntəɾaːtmaː kiː deːn pɾaːpt hɛː ɔːɾ pəɾəspəɾ ʊnʱẽː bʱaːiːtʃaːɾeː keː bʱaːʋ seː bəɾtaːʋ kəɾnə tʃaːhɪeː ‖]

- Gloss (word-to-word)

- Article 1 (one) – All human-beings to dignity and rights' matter in from-birth freedom and equality acquired is. Them to reason and conscience's endowment acquired is and always them to brotherhood's spirit with behaviour to do should.

- Translation (grammatical)

- Article 1 – All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.

See also

- Hindi Belt

- Bengali Language Movement (Manbhum)

- Hindi Divas – the official day to celebrate Hindi as a language.

- Languages of India

- Languages with official status in India

- Indian States by most popular languages

- List of English words of Hindi or Urdu origin

- List of Hindi television channels broadcast in Europe (by country)

- List of Hindi channels in Europe (by type)

- List of languages by number of native speakers in India

- List of Sanskrit and Persian roots in Hindi

- World Hindi Secretariat

References

Notes

- "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength - 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India. 29 June 2018.

- Hindi at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- Hindustani (2005). Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- "Central Hindi Directorate: Introduction". Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Hindi". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Singh, Rajendra, and Rama Kant Agnihotri. Hindi morphology: A word-based description. Vol. 9. Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1997.

- "Constitution of India". Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- "About Hindi-Urdu". North Carolina State University. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- Basu, Manisha (2017). The Rhetoric of Hindutva. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-14987-8.

Urdu, like Hindi, was a standardized register of the Hindustani language deriving from the Delhi dialect and emerged in the eighteenth century under the rule of the late Mughals.

- Peter-Dass, Rakesh (2019). Hindi Christian Literature in Contemporary India. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-00-070224-8.

Two forms of the same language, Nagarai Hindi and Persianized Hindi (Urdu) had identical grammar, shared common words and roots, and employed different scripts.

- "Constitutional Provisions: Official Language Related Part-17 of The Constitution Of India". Department of Official Language, Government of India. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "How languages intersect in India". Hindustan Times. 22 November 2018.

- "How many Indians can you talk to?". www.hindustantimes.com. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "Hindi and the North-South divide". 9 October 2018.

- Pillalamarri, Akhilesh. "India's Evolving Linguistic Landscape". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "PART A Languages specified in the Eighth Schedule (Scheduled Languages)". Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- "How many Indians can you talk to?".

- "Hindi Diwas 2018: Hindi travelled to these five countries from India". 14 September 2018.

- "Sequence of events with reference to official language of the Union". Archived from the original on 2 August 2011.

- रिपब्लिक ऑफ फीजी का संविधान (Constitution of the Republic of Fiji, the Hindi version) Archived 1 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Caribbean Languages and Caribbean Linguistics" (PDF). University of the West Indies Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- Richard K. Barz (8 May 2007). "The cultural significance of Hindi in Mauritius". South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 3: 1–13. doi:10.1080/00856408008722995.

- Gube, Jan; Gao, Fang (2019). Education, Ethnicity and Equity in the Multilingual Asian Context. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-981-13-3125-1.

The national language of India and Pakistan 'Standard Urdu' is mutually intelligible with 'Standard Hindi' because both languages share the same Indic base and are all but indistinguishable in phonology and grammar (Lust et al. 2000).

- Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin. Asterisks mark the 2010 estimates Archived 11 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine for the top dozen languages.

- Gambhir, Vijay (1995). The Teaching and Acquisition of South Asian Languages. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3328-5.

The position of Hindi-Urdu among the languages of the world is anomalous. The number of its proficient speakers, over three hundred million, places it in third of fourth place after Mandarin, English, and perhaps Spanish.

- "Hindustani". Columbia University Press. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017 – via encyclopedia.com.

- Steingass, Francis Joseph (1892). A comprehensive Persian-English dictionary. London: Routledge & K. Paul. p. 1514. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- Khan, Rajak. "Indo-Persian Literature and Amir Khusro". University of Delhi. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- Losensky, Paul E. (15 July 2013). In the Bazaar of Love: The Selected Poetry of Amir Khusrau. Penguin UK. ISBN 9788184755220 – via Google Books.

- Mihir Bose (18 April 2006). The Magic of Indian Cricket: Cricket and Society in India. Routledge. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-1-134-24924-4.

- "India". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- "Brief History of Hindi". Central Hindi Directorate. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

The primary sources of non-IA loans into MSH are Arabic, Persian, Portuguese, Turkic and English. Conversational registers of Hindi/Urdu (not to mentioned formal registers of Urdu) employ large numbers of Persian and Arabic loanwords, although in Sanskritized registers many of these words are replaced by tatsama forms from Sanskrit. The Persian and Arabic lexical elements in Hindi result from the effects of centuries of Islamic administrative rule over much of north India in the centuries before the establishment of British rule in India. Although it is conventional to differentiate among Persian and Arabic loan elements into Hindi/Urdu, in practice it is often difficult to separate these strands from one another. The Arabic (and also Turkic) lexemes borrowed into Hindi frequently were mediated through Persian, as a result of which a thorough intertwining of Persian and Arabic elements took place, as manifest by such phenomena as hybrid compounds and compound words. Moreover, although the dominant trajectory of lexical borrowing was from Arabic into Persian, and thence into Hindi/Urdu, examples can be found of words that in origin are actually Persian loanwords into both Arabic and Hindi/Urdu.

- The Formation of Modern Hindi as Demonstrated in Early 'Hindi' Dictionaries. Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. 2001. p. 28.

- First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. Brill Academic Publishers. 1993. p. 1024. ISBN 9789004097964.

Whilst the Muhammadan rulers of India spoke Persian, which enjoyed the prestige of being their court language, the common language of the country continued to be Hindi, derived through Prakrit from Sanskrit. On this dialect of the common people was grafted the Persian language, which brought a new language, Urdu, into existence. Sir George Grierson, in the Linguistic Survey of India, assigns no distinct place to Urdu, but treats it as an offshoot of Western Hindi.

- Mody, Sujata Sudhakar (2008). Literature, Language, and Nation Formation: The Story of a Modern Hindi Journal 1900-1920. University of California, Berkeley. p. 7.

...Hindustani, Rekhta, and Urdu as later names of the old Hindi (a.k.a. Hindavi).

- John Joseph Gumperz (1971). Language in Social Groups. Stanford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8047-0798-5. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Tracing the Boundaries Between Hindi and Urdu: Lost and Added in Translation Between 20th Century Short Stories. BRILL. 2010. p. 138. ISBN 9789004177314.

- Turek, Aleksandra. "Is the Dhola Maru ra duha only a poetic elaboration?". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Shapiro 2003, p. 280

- "Rekhta: Poetry in Mixed Language, The Emergence of Khari Boli Literature in North India" (PDF). Columbia University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 August 2006. Retrieved 9 October 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Paul R. Brass (2005). Language, Religion and Politics in North India. iUniverse, Incorporated. ISBN 9780595343942.

- Parthasarathy, Kumar, p.120

- Clyne, Michael (24 May 2012). Pluricentric Languages: Differing Norms in Different Nations. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110888140.

- Choudhry, Sujit; Khosla, Madhav; Mehta, Pratap Bhanu (12 May 2016). The Oxford Handbook of the Indian Constitution. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191058615.

- Grewal, J. S. (8 October 1998). The Sikhs of the Punjab. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521637640.

- "हिन्दी दिवस विशेष: इनके प्रयास से मिला था हिन्दी को राजभाषा का दर्जा". Archived from the original on 11 September 2017.

- "Hindi Diwas celebration: How it all began". The Indian Express. 14 September 2016. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- "The Constitution of India" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2014.

- "Rajbhasha" (PDF) (in Hindi and English). india.gov.in. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2012.

- "THE OFFICIAL LANGUAGES ACT, 1963 (AS AMENDED, 1967) (Act No. 19 of 1963)". Department of Official Language. Archived from the original on 16 December 2016. Retrieved 9 June 2016.

- "Report of the Commissioner for linguistic minorities: 50th report (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- Roy, Anirban (27 May 2011). "West Bengal to have six more languages for official use". India Today. Retrieved 10 January 2020.

- Roy, Anirban (28 February 2018). "Kamtapuri, Rajbanshi make it to list of official languages in". India Today. Archived from the original on 30 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Sen, Sumant (4 June 2019). "Hindi the first choice of people in only 12 States". The Hindu.

- "Why Hindi isn't the national language".

- Khan, Saeed (25 January 2010). "There's no national language in India: Gujarat High Court". The Times of India. Ahmedabad: The Times Group. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- "Hindi, not a national language: Court". The Hindu. Ahmedabad: Press Trust of India. 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- "Gujarat High Court order". The Hindu. 25 January 2010. Archived from the original on 4 July 2014.

- "Population Monograph of Nepal, Vol. 2" (PDF). Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics. 2014. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- "Hindi, Fiji". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- "Fiji Hindi alphabet, pronunciation and language". www.omniglot.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- "Section 4 of Fiji Constitution". servat.unibe.ch. Archived from the original on 9 June 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2009.

- "Constitution of Fiji". Official site of the Fijian Government. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Kothari, Ria, ed. (2011). Chutnefying English: The Phenomenon of Hinglish. Penguin Books India. p. 128. ISBN 9780143416395.

- How Hindi became the language of choice in Arunachal Pradesh Archived 11 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Gandapur, Khalid Amir Khan (19 September 2012). "Has Hindi become our national language?". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Hakala, Walter N. (2012). "Languages as a Key to Understanding Afghanistan's Cultures" (PDF). National Geographic. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

In the 1980s and '90s, at least three million Afghans--mostly Pashtun--fled to Pakistan, where a substantial number spent several years being exposed to Hindi- and Urdu-language media, especially Bollywood films and songs, and beng educated in Urdu-language schools, both of which contributed to the decline of Dari, even among urban Pashtuns.

- Krishnamurthy, Rajeshwari (28 June 2013). "Kabul Diary: Discovering the Indian connection". Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

Most Afghans in Kabul understand and/or speak Hindi, thanks to the popularity of Indian cinema in the country.

- "Hindi most spoken Indian language in US, Telugu speakers up 86% in 8 years".

- "United States- Languages". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- Frawley, p. 481

- "United Kingdom- Languages". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- "Hindi and Urdu are classified as literary registers of the same language". Archived from the original on 2 June 2016.

- Kuiper, Kathleen (2010). The Culture of India. Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61530-149-2.

Urdu is closely related to Hindi, a language that originated and developed in the Indian subcontinent. They share the same Indic base and are so similar in phonology and grammar that they appear to be one language.

- Chatterji, Suniti Kumar; Siṃha, Udaẏa Nārāẏana; Padikkal, Shivarama (1997). Suniti Kumar Chatterji: a centenary tribute. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-0353-2.

High Hindi written in Devanagari, having identical grammar with Urdu, employing the native Hindi or Hindustani (Prakrit) elements to the fullest, but for words of high culture, going to Sanskrit. Hindustani proper that represents the basic Khari Boli with vocabulary holding a balance between Urdu and High Hindi.

- Sin, Sarah J. (2017). Bilingualism in Schools and Society: Language, Identity, and Policy, Second Edition. Routledge. ISBN 9781315535555. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- Bhatia, Tej K. (1987). A History of the Hindi Grammatical Tradition: Hindi-Hindustani Grammar, Grammarians, History and Problems. Brill. ISBN 9789004079243.

- Masica, p. 65

- Masica, p. 66

- Masica, p. 67

- Arnold, David; Robb, Peter (2013). Institutions and Ideologies: A SOAS South Asia Reader. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 9781136102349.

- Ohala, Manjari (1983). Aspects of Hindi Phonology. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 38. ISBN 9780895816702.

- Arnold, David; Robb, Peter (2013). Institutions and Ideologies: A SOAS South Asia Reader. Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 9781136102349.

- Kachru, Yamuna (2006). Hindi. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 9789027238122.

- Bhatia, Tej K.; Ritchie, William C. (2006). The Handbook of Bilingualism. John Wiley and Sons. p. 789. ISBN 9780631227359.

- D., S. (10 February 2011). "Arabic and Hindi". The Economist. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- "Stop outraging over Marathi – Hindi and English chauvinism is much worse in India". Archived from the original on 19 September 2015.

- "Hindi content consumption on internet growing at 94%: Google". The Economic Times. 18 August 2015. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

Bibliography

- Bhatia, Tej K. (11 September 2002). Colloquial Hindi: The Complete Course for Beginners. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-134-83534-8. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Grierson, G. A. Linguistic Survey of India Vol I-XI, Calcutta, 1928, ISBN 81-85395-27-6 (searchable database).

- Koul, Omkar N. (2008). Modern Hindi grammar (PDF). Springfield, VA: Dunwoody Press. ISBN 978-1-931546-06-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- McGregor, R.S. (1995). Outline of Hindi grammar: With exercises (3. ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Pr. ISBN 978-0-19-870008-1. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Frawley, William (2003). International Encyclopedia of Linguistics: AAVE-Esparanto. Vol.1. Oxford University Press. p. 481. ISBN 978-0-195-13977-8.

- Parthasarathy, R.; Kumar, Swargesh (2012). Bihar Tourism: Retrospect and Prospect. Concept Publishing Company. p. 120. ISBN 978-8-180-69799-9.

- Masica, Colin (1991). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Ohala, Manjari (1999). "Hindi". In International Phonetic Association (ed.). Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: a Guide to the Use of the International Phonetic Alphabet. Cambridge University Press. pp. 100–103. ISBN 978-0-521-63751-0.

- Sadana, Rashmi (2012). English Heart, Hindi Heartland: the Political Life of Literature in India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26957-6. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- Shapiro, Michael C. (2001). "Hindi". In Garry, Jane; Rubino, Carl (eds.). An encyclopedia of the world's major languages, past and present. New England Publishing Associates. pp. 305–309.

- Shapiro, Michael C. (2003). "Hindi". In Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 250–285. ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- Snell, Rupert; Weightman, Simon (1989). Teach Yourself Hindi (2003 ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-142012-9.

- Taj, Afroz (2002) A door into Hindi. Retrieved 8 November 2005.

- Tiwari, Bholanath ([1966] 2004) हिन्दी भाषा (Hindī Bhasha), Kitab Pustika, Allahabad, ISBN 81-225-0017-X.

Dictionaries

- McGregor, R.S. (1993), Oxford Hindi–English Dictionary (2004 ed.), Oxford University Press, USA.

- Hardev Bahri (1989), Learners' Hindi-English dictionary, Delhi: Rajapala

- Mahendra Caturvedi (1970), A practical Hindi-English dictionary, Delhi: National Publishing House

- Academic Room Hindi Dictionary Mobile App developed in the Harvard Innovation Lab (iOS, Android and Blackberry)

- John Thompson Platts (1884), A dictionary of Urdū, classical Hindī, and English (reprint ed.), LONDON: H. Milford, p. 1259, retrieved 6 July 2011

Further reading

- Bhatia, Tej K A History of the Hindi Grammatical Tradition. Leiden, Netherlands & New York, NY: E.J. Brill, 1987. ISBN 90-04-07924-6

External links

| Hindi edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Hindi. |

- Hindi at Curlie

- Hindi language at Encyclopædia Britannica

- The Union: Official Language

- Official Unicode Chart for Devanagari (PDF)

- list of Hindi words at Wiktionary, the free dictionary