Madang languages

The Madang or Madang–Adelbert Range languages are a language family of Papua New Guinea. They were classified as a branch of Trans–New Guinea by Stephen Wurm, followed by Malcolm Ross. William A. Foley concurs that it is "highly likely" that the Madang languages are part of TNG, although the pronouns, the usual basis for classification in TNG, have been "replaced" in Madang. Timothy Usher finds that Madang is closest to the Upper Yuat River languages and other families to its west, but does not for now address whether this larger group forms part of the TNG family.[1]

| Madang | |

|---|---|

| Madang–Adelbert Range | |

| Geographic distribution | Papua New Guinea |

| Linguistic classification | Northeast New Guinea and/or Trans–New Guinea

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | mada1298[2] |

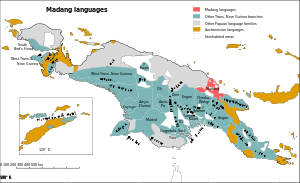

Map: The Madang languages of New Guinea

The Madang languages

Trans–New Guinea languages

Other Papuan languages

Austronesian languages

Uninhabited | |

The family is named after Madang Province and the Adelbert Range.

History

Sidney Herbert Ray identified the Rai Coast family in 1919. In 1951 these were linked with the Mabuso languages by Arthur Capell to create his Madang family. John Z'graggen (1971, 1975) expanded Madang to languages of the Adelbert Range and renamed the family Madang–Adelbert Range, and Wurm (1975)[3] adopted this as a branch of his Trans–New Guinea phylum. For the most part, Ross's (2005) Madang family includes the same languages as Z'graggen Madang–Adelbert Range, but the internal classification is different in several respects, such as the dissolution of the Brahman branch.

Internal classification

The languages are as follows:[1][4]

- ? Yamben

- Bargam (Mugil)

- Central Madang

- West Madang

- Southern Adelbert Range (Ramu Tributaries)

- Kalam (West Madang Highlands)

- East Madang

Yamben has been added as a probable primary branch of Madang by Andrew Pick (2019).[4]

The time depth of Madang is comparable to that of Austronesian or Indo-European.

Pronouns

Ross (2000) reconstructed the pronouns as follows:

sg pl 1 *ya *i[5] 2 *na *ni, *ta 3 *nu

These are not the common TNG pronouns. However, Ross postulates that the TNG dual suffixes *-le and *-t remain, and suggests that the TNG pronouns live on as Kalam verbal suffixes.

Evolution

Madang family reflexes of proto-Trans-New Guinea (pTNG) etyma:[6]

Family-wide innovations

- pTNG *mbena ‘arm’ > proto-Madang *kambena (accretion of *ka-)

- pTNG *mb(i,u)t(i,u)C ‘fingernail’ > proto-Madang *timbi(n,t) (metathesis)

- pTNG *(n)ok ‘water’ replaced by proto-Madang *yaŋgu

Croisilles

Garuh language:

- muki ‘brain’ < *muku

- bi ‘guts’ < *simbi

- hap ‘cloud’ < *samb(V)

- balamu ‘firelight’ < *mbalaŋ

- wani ‘name’ < *[w]ani ‘who?’

- wus ‘wind, breeze’ < *kumbutu

- kalam ‘moon’ < *kala(a,i)m

- neg- ‘to watch’ < *nVŋg- ‘see, know’

- ma ‘taro’ < *mV

- ahi ‘sand’ < *sa(ŋg,k)asiŋ

Pay language:

- in- ‘sleep’ < *kin(i,u)-

- kawus ‘smoke’ < *kambu

- tawu-na ‘ashes’ < *sambu

- imun ‘hair’ < *sumu(n,t)

- ano ‘who’ < *[w]ani

Kalam

Kalam language (most closely related to the Rai Coast languages):

- meg ‘teeth’ < *maŋgat[a]

- md-magi ‘heart’ < *mundu-maŋgV

- mkem ‘cheek’ < *mVkVm ‘cheek, chin’

- sb ‘excrement, guts’ < *simbi

- muk ‘milk, sap, brain’ < *muku

- yman ‘louse’ < *iman

- yb ‘name’ < *imbi

- kdl ‘root’ < *kindil

- malaŋ ‘flame’ < *mbalaŋ

- melk ‘(fire or day)light’ < *(m,mb)elak

- kn- ‘to sleep, lie down’ < *kini(i,u)[m]-

- kum- ‘die’ < *kumV-

- md- < *mVna- ‘be, stay’

- nŋ-, ng- ‘perceive, know, see, hear, etc’ < *nVŋg-

- kawnan ‘shadow, spirit’ < *k(a,o)

- nan, takn ‘moon’ < *takVn[V]

- magi ‘round thing, egg, fruit, etc.’ < *maŋgV

- ami ‘mother’ < *am(a,i,u)

- b ‘man’ < *ambi

- bapi, -ap ‘father’ < *mbapa, *ap

- saŋ ‘women’s dancing song’ < *saŋ

- ma- ‘negator’ < *ma-

- an ‘who’ < *[w]ani

Rai Coast

Dumpu language:

- man- ‘be, stay’ < *mVna-

- mekh ‘teeth’ < *maŋgat[a]

- im ‘louse’ < *iman

- munu ‘heart’ < *mundun ‘inner organs’

- kum- ‘die’ < *kumV-

- kono ‘shadow’ < *k(a,o)nan

- kini- ‘sleep’ < *kin(i,u)[m]-

- ra- ‘take’ < *(nd,t)a-

- urau ‘long’ < *k(o,u)ti(mb,p)V

- gra ‘dry’ < *(ŋg,k)atata

Southern Adelbert

- mun(zera) ‘be, stay’ < *mVna-

- kaja ‘blood’ < *kenja

- miku ‘brain’ < *muku

- simbil ‘guts’ < *simbi

- tipi ‘fingernail’ < *mb(i,)ut(i,u)C (metathesis)

- iːma ‘louse’ < *iman

- ibu ‘name’ < *imbi

- kanumbu ‘wind’ < *kumbutu

- mundu(ma) ‘nose’ < *mundu

- kaːsi ‘sand’ < *sa(ŋg,k)asiŋ

- apapara ‘butterfly’ < *apa(pa)ta

- kumu- ‘die’ < *kumV-

- ŋg- ‘see’ < *nVŋg-

Notes

- Madang

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Madang". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Ethnologue (15th edition)

- Pick, Andrew (2019). "Yamben: A previously undocumented language of Madang" (PDF). 5th Workshop on the Languages of Papua. Universitas Negeri Papua, Manokwari, West Papua, Indonesia.

- actually i ~ si

- Pawley, Andrew; Hammarström, Harald (2018). "The Trans New Guinea family". In Palmer, Bill (ed.). The Languages and Linguistics of the New Guinea Area: A Comprehensive Guide. The World of Linguistics. 4. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 21–196. ISBN 978-3-11-028642-7.

References

- Ross, Malcolm (2005). "Pronouns as a preliminary diagnostic for grouping Papuan languages". In Andrew Pawley; Robert Attenborough; Robin Hide; Jack Golson (eds.). Papuan pasts: cultural, linguistic and biological histories of Papuan-speaking peoples. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 15–66. ISBN 0858835622. OCLC 67292782.

- Pawley, Ross, & Osmond, 2005. Papuan languages and the Trans New Guinea phylum. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 38–51.

Further reading

- Ross, Malcolm. 2014. Proto-Madang. TransNewGuinea.org.

- Robert Forkel, Simon J Greenhill, Johann-Mattis List, & Tiago Tresoldi. (2019). lexibank/zgraggenmadang: Madang Comparative Wordlists (Version v3.0) [Data set]. Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.3537580

External links

- The Madang–Adelbert Range languages in Multitree, showing both Z'graggen's and Wurm's classifications [no longer functional as of 2014]

- ELAR archive of Documenting the Sogeram Language Family of Papua New Guinea