Human overpopulation

Human overpopulation (or population overshoot) is when there are too many people for the environment to sustain (with food, drinkable water, breathable air, etc.). In more scientific terms, there is overshoot when the ecological footprint of a human population in a geographical area exceeds that place's carrying capacity, damaging the environment faster than it can be repaired by nature, potentially leading to an ecological and societal collapse. Overpopulation could apply to the population of a specific region, or to world population as a whole.[1]

Overpopulation can result from an increase in births, a decline in mortality rates, an increase in immigration, or an unsustainable biome and depletion of resources.

Advocates of population moderation cite issues like exceeding the Earth's carrying capacity, global warming, potential or imminent ecological collapse, impact on quality of life, and risk of mass starvation or even extinction as a basis to argue for population decline.

A more controversial definition of overpopulation, as advocated by Paul Ehrlich, is a situation where a population is in the process of depleting non-renewable resources. Under this definition, changes in lifestyle could cause an overpopulated area to no longer be overpopulated without any reduction in population, or vice versa.[2][3][4]

Scientists suggest that the overall human impact on the environment, due to overpopulation, overconsumption, pollution, and proliferation of technology, has pushed the planet into a new geological epoch known as the Anthropocene.[5][6][7][8]

Current population dynamics, and cause for concern

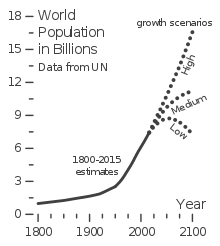

As of August 17, 2020, the world's human population is estimated to be 7.81 billion.[9] Or, 7,622,106,064 on 14 May 2018 and the United States Census Bureau calculates 7,472,985,269 for that same date[10] and over 7 billion by the United Nations.[11][12][13] Most contemporary estimates for the carrying capacity of the Earth under existing conditions are between 4 billion and 9 billion . Depending on which estimate is used, human overpopulation may have already occurred.

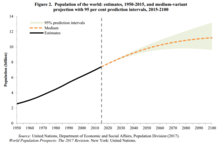

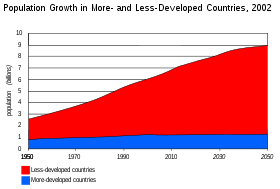

Nevertheless, the rapid recent increase in human population has worried some people. The population is expected to reach between 8 and 10.5 billion between the years 2040[14][15] and 2050.[16] In 2017, the United Nations increased the medium variant projections[17] to 9.8 billion for 2050 and 11.2 billion for 2100.[18]

As pointed out by Hans Rosling, the critical factor is that the population is not "just growing", but that the growth ratio reached its peak and the total population is now growing much slower.[19] The UN population forecast of 2017 was predicting "near end of high fertility" globally and anticipating that by 2030 over ⅔ of world population will be living in countries with fertility below the replacement level[20] and for total world population to stabilize between 10-12 billion people by year 2100.[21]

The rapid increase in world population over the past three centuries has raised concerns among some people that the planet may not be able to sustain the future or even present number of its inhabitants. The InterAcademy Panel Statement on Population Growth, circa 1994, stated that many environmental problems, such as rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide, global warming, and pollution, are aggravated by the population expansion.[22]

Other problems associated with overpopulation include the increased demand for resources such as fresh water and food, starvation and malnutrition, consumption of natural resources (such as fossil fuels) faster than the rate of regeneration, and a deterioration in living conditions.

Wealthy but densely populated territories like Britain rely on food imports from overseas.[23] This was severely felt during the World Wars when, despite food efficiency initiatives like "dig for victory" and food rationing, Britain needed to fight to secure import routes. However, many believe that waste and over-consumption, especially by wealthy nations, is putting more strain on the environment than overpopulation itself.[24]

History

World population has been rising continuously since the end of the Black Death, around the year 1350,[25] although the most significant increase has been since the 1950s, mainly due to medical advancements and increases in agricultural productivity.

Due to its dramatic impact on the human ability to grow food, the Haber process served as the "detonator of the population explosion", enabling the global population to increase from 1.6 billion in 1900 to 7.7 billion by November 2018.[26]

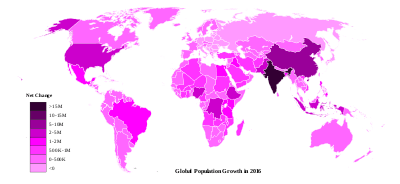

The rate of population growth has been declining since the 1980s, while the absolute total numbers are still increasing. Recent rate increases in several countries previously enjoying steady declines have apparently been contributing to continued growth in total numbers. The United Nations has expressed concerns on continued population growth in sub-Saharan Africa.[27] Recent research has demonstrated that those concerns are well grounded.[28][29][30]

History of concern

Concern about overpopulation is an ancient topic. Tertullian was a resident of the city of Carthage in the second century CE, when the population of the world was about 190 million (only 3–4% of what it is today). He notably said: "What most frequently meets our view (and occasions complaint) is our teeming population. Our numbers are burdensome to the world, which can hardly support us... In very deed, pestilence, and famine, and wars, and earthquakes have to be regarded as a remedy for nations, as the means of pruning the luxuriance of the human race." Before that, Plato, Aristotle and others broached the topic as well.[31]

Throughout recorded history, population growth has usually been slow despite high birth rates, due to war, plagues and other diseases, and high infant mortality. During the 750 years before the Industrial Revolution, the world's population increased very slowly, remaining under 250 million.[32]

By the beginning of the 19th century, the world population had grown to a billion individuals, and intellectuals such as Thomas Malthus predicted that humankind would outgrow its available resources because a finite amount of land would be incapable of supporting a population with limitless potential for increase.[33] Mercantillists argued that a large population was a form of wealth, which made it possible to create bigger markets and armies. The rich have always known that the real value of their fortune is "how much labor will it purchase?" This because almost all things humans value are only frozen labor. So the more numerous and poorer the population, the less those workers can charge for their labor.

During the 19th century, Malthus' work was often interpreted in a way that blamed the poor alone for their condition and helping them was said to worsen conditions in the long run.[34] This resulted, for example, in the English poor laws of 1834[34] and a hesitating response to the Irish Great Famine of 1845–52.[35]

The UN publication 'World population prospects' (2017) projects that the world population will reach 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion in 2100. The human population is predicted to stabilize soon thereafter.

A 2014 study published in Science asserts that population growth will continue into the next century.[36][37] Adrian Raftery, a University of Washington professor of statistics and sociology and one of the contributors to the study, says: "The consensus over the past 20 years or so was that world population, which is currently around 7 billion, would go up to 9 billion and level off or probably decline. We found there's a 70 percent probability the world population will not stabilize this century. Population, which had sort of fallen off the world's agenda, remains a very important issue."[38] UN projections from 2011 suggest the population could grow to as many as 15 billion by 2100.[39]

In 2017, more than one-third of 50 Nobel prize-winning scientists surveyed by the Times Higher Education at the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings said that human overpopulation and environmental degradation are the two greatest threats facing humankind.[40] In November that same year, a statement by 15,364 scientists from 184 countries indicated that rapid human population growth is the "primary driver behind many ecological and even societal threats."[41]

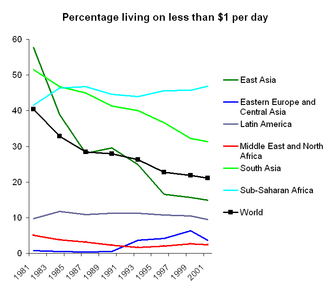

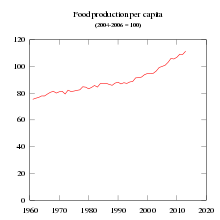

In spite of concerns about overpopulation, widespread in developed countries, the number of people living in extreme poverty globally shows a stable decline (this has been disputed by some experts[42][43][44]), even though the population has grown seven-fold over the last 200 years. Child mortality has declined, which in turn has led to reduced birth rates, thus slowing overall population growth.[45] The global number of famine-related deaths have declined, and food supply per person has increased with population growth.[46]

In 2019, a warning on climate change signed by 11,000 scientists from 153 nations said that human population growth adds 80 million humans annually, and "the world population must be stabilized—and, ideally, gradually reduced—within a framework that ensures social integrity" to reduce the impact of "population growth on GHG emissions and biodiversity loss."[47][48]

History of population growth

| Population[27] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Billion | ||

| 1804 | 1 | ||

| 1927 | 2 | ||

| 1959 | 3 | ||

| 1974 | 4 | ||

| 1987 | 5 | ||

| 1999 | 6 | ||

| 2011 | 7 | ||

| 2020 | 7.8[49] | ||

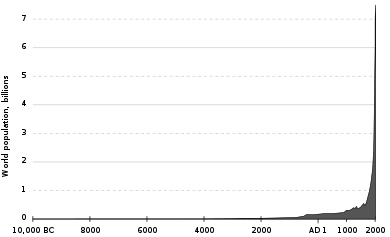

World population has gone through a number of periods of growth since the dawn of civilization in the Holocene period, around 10,000 BCE. The beginning of civilization roughly coincides with the receding of glacial ice following the end of the last glacial period.[50] It is estimated that between 1–5 million people, subsisting on hunting and foraging, inhabited the Earth in the period before the Neolithic Revolution, when human activity shifted away from hunter-gathering and towards very primitive farming.[51]

Around 8000 BCE, at the dawn of agriculture, the human population of the world was approximately 5 million.[52] The next several millennia saw a steady increase in the population, with very rapid growth beginning in 1000 BCE, and a peak of between 200 and 300 million people in 1 BCE.

The Plague of Justinian caused Europe's population to drop by around 50% between 541 and the 8th century.[53] Steady growth resumed in 800 CE.[54] However, growth was again disrupted by frequent plagues; most notably, the Black Death during the 14th century. The effects of the Black Death are thought to have reduced the world's population, then at an estimated 450 million, to between 350 and 375 million by 1400.[55] The population of Europe stood at over 70 million in 1340;[56] these levels did not return until 200 years later.[57] England's population reached an estimated 5.6 million in 1650, up from an estimated 2.6 million in 1500.[58] New crops from the Americas via the Spanish colonizers in the 16th century contributed to the population growth.[59]

In other parts of the globe, China's population census at the founding of the Ming dynasty in 1368 indicated that the population stood close to 60 million, (though these figures are debated by some historians) approaching 150 million by the end of the dynasty in 1644.[60][61] The population of the Americas in 1500 may have been between 50 and 100 million.[62]

Encounters between European explorers and populations in the rest of the world often introduced local epidemics of extraordinary virulence. Archaeological evidence indicates that the death of around 90% of the Native American population of the New World was caused by Old World diseases such as smallpox, measles, and influenza.[63] Europeans introduced diseases alien to the indigenous people, therefore they did not have immunity to these foreign diseases.[64]

After the start of the Industrial Revolution, during the 18th century, the rate of population growth began to increase. By the end of the century, the world's population was estimated at just under 1 billion.[65] At the turn of the 20th century, the world's population was roughly 1.6 billion.[65] By 1940, this figure had increased to 2.3 billion.[66] Each subsequent addition of a billion humans took less and less time: 33 years to reach three billion in 1960, 14 years for four billion in 1974, 13 years for five billion in 1987, and 12 years for six billion in 1999.[67]

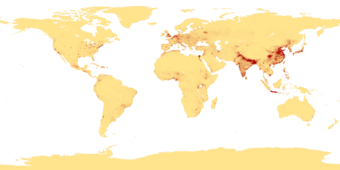

Dramatic growth beginning in 1950 (above 1.8% per year) coincided with greatly increased food production as a result of the industrialization of agriculture brought about by the Green Revolution.[68] The rate of human population growth peaked in 1964, at about 2.1% per year.[69] For example, Indonesia's population grew from 97 million in 1961 to 237.6 million in 2010,[70][71] a 145% increase in 49 years. In India, the population grew from 361.1 million people in 1951 to just over 1.2 billion by 2011,[72][73] a 235% increase in 60 years.

| Continent | 1900 population[74] |

|---|---|

| Africa | 133 million |

| Asia | 904 million |

| Europe | 408 million |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 74 million |

| North America | 82 million |

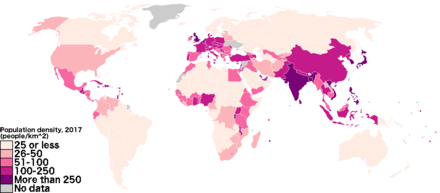

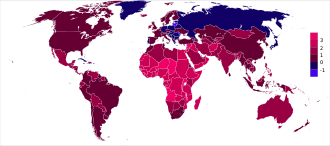

There is concern over the sharp population increase in many countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, that has occurred over the last several decades, and that it is creating problems with land management, natural resources and access to water supplies.[75]

The population of Chad has, for example, grown from 6,279,921 in 1993 to 10,329,208 in 2009.[76] Niger, Uganda, Nigeria, Tanzania, Ethiopia and the DRC are witnessing a similar growth in population. The situation is most acute in western, central and eastern Africa.[77] Refugees from places like Sudan have further strained the resources of neighboring states like Chad and Egypt. Chad is also host to roughly 255,000 refugees from Sudan's Darfur region, and about 77,000 refugees from the Central African Republic, while approximately 188,000 Chadians have been displaced by their own civil war and famines, have either fled to either the Sudan, the Niger or, more recently, Libya.[78]

According to UN data, there are on average 250 babies born each minute, or more than 130 million a year.[79] UN data from 2019 shows that the human population grows by 100 million every 14 months.[80]

Causes

From a historical perspective, technological revolutions have coincided with population expansion. There have been three major technological revolutions – the tool-making revolution, the agricultural revolution, and the industrial revolution – all of which allowed humans more access to food, resulting in subsequent population explosions.[81] For example, the use of tools, such as bow and arrow, allowed primitive hunters greater access to more high energy foods (e.g. animal meat). Similarly, the transition to farming about 10,000 years ago greatly increased the overall food supply, which was used to support more people. Food production further increased with the industrial revolution as machinery, fertilizers, herbicides, and pesticides were used to increase land under cultivation as well as crop yields. Today, starvation is caused by economic and political forces rather than a lack of the means to produce food.[82][83]

Significant increases in human population occur whenever the birth rate exceeds the death rate for extended periods of time. Traditionally, the fertility rate is strongly influenced by cultural and social norms that are rather stable and therefore slow to adapt to changes in the social, technological, or environmental conditions. For example, when death rates fell during the 19th and 20th century – as a result of improved sanitation, child immunizations, and other advances in medicine – allowing more newborns to survive, the fertility rate did not adjust downward, resulting in significant population growth. Until the 1700s, seven out of ten children died before reaching reproductive age.[84] Today, more than nine out of ten children born in industrialized nations reach adulthood.

Donella Meadows argued a correlation between overpopulation and poverty.[85] In contrast, the invention of the birth control pill and other modern methods of contraception resulted in a dramatic decline in the number of children per household in all but the very poorest countries.[86]

Agriculture has sustained human population growth and has been the main driving factor behind it. With more food supply, the population grows with it. This occurs most in regions which are fertile and capable of higher food production in contrast to barren regions unable to support crop production on larger or any scales at all. This dates back to prehistoric times, when agricultural methods were first developed, and continues to the present day, with fertilizers, agrochemicals, large-scale mechanization, genetic manipulation, and other technologies.[87][88][89][90]

Humans have historically exploited the environment using the easiest, most accessible resources first. The richest farmland was plowed and the richest mineral ore mined first. Anne Ehrlich, Gerardo Ceballos, and Paul Ehrlich note that overpopulation is demanding the use of ever more creative, expensive and/or environmentally destructive means in order to exploit ever more difficult to access and/or poorer quality natural resources to satisfy consumers.[91]

Population as a function of food availability

Many people from a wide range of academic fields and political backgrounds—including agronomist David Pimentel,[92] behavioral scientist Russell Hopfenberg,[93] anthropologist Virginia Abernethy,[94] ecologist Garrett Hardin,[95] science writer and anthropologist Peter Farb, journalist Richard Manning,[96] environmental biologist Alan D. Thornhill,[97] cultural critic and writer Daniel Quinn,[98] and anarcho-primitivist John Zerzan,[99]—propose that, like all other animal populations, human populations predictably grow and shrink according to their available food supply, growing during an abundance of food and shrinking in times of scarcity.

Proponents of this theory argue that every time food production is increased, the population grows. Most human populations throughout history validate this theory, as does the overall current global population. Populations of hunter-gatherers fluctuate in accordance with the amount of available food. The world human population began increasing after the Neolithic Revolution and its increased food supply.[100] This was, subsequent to the Green Revolution, followed by even more severely accelerated population growth, which continues today. Often, wealthier countries send their surplus food resources to the aid of starving communities; however, proponents of this theory argue that this seemingly beneficial notion only results in further harm to those communities in the long run. Peter Farb, for example, has commented on the paradox that "intensification of production to feed an increased population leads to a still greater increase in population."[101] Daniel Quinn has also focused on this phenomenon, which he calls the "Food Race" (comparable, in terms of both escalation and potential catastrophe, to the nuclear arms race).

Critics of this theory point out that, in the modern era, birth rates are lowest in the developed nations, which also have the highest access to food. In fact, some developed countries have both a diminishing population and an abundant food supply. The United Nations projects that the population of 51 countries or areas, including Germany, Italy, Japan, and most of the states of the former Soviet Union, is expected to be lower in 2050 than in 2005.[102] This shows that, limited to the scope of the population living within a single given political boundary, particular human populations do not always grow to match the available food supply. However, the global population as a whole still grows in accordance with the total food supply and many of these wealthier countries are major exporters of food to poorer populations, so that, "it is through exports from food-rich to food-poor areas (Allaby, 1984; Pimentel et al., 1999) that the population growth in these food-poor areas is further fueled.[103]

Regardless of criticisms against the theory that population is a function of food availability, the human population is, on the global scale, undeniably increasing,[104] as is the net quantity of human food produced—a pattern that has been true for roughly 10,000 years, since the human development of agriculture. The fact that some affluent countries demonstrate negative population growth fails to discredit the theory as a whole, since the world has become a globalized system with food moving across national borders from areas of abundance to areas of scarcity. Hopfenberg and Pimentel's findings support both this[92] and Quinn's direct accusation that "First World farmers are fueling the Third World population explosion."[105]

Dangers and effects

Many of the problems associated with overpopulation are explored in the dystopic science fiction film Soylent Green, where an overpopulated Earth suffers from food shortages, depleted resources and poverty and in the documentary Aftermath: Population Overload, which explores what would happen if the human population suddenly doubled in size.

David Attenborough described the level of human population on the planet as a multiplier of all other environmental problems.[106] In 2013, he described humanity as "a plague on the Earth" that needs to be controlled by limiting population growth.[107]

Most biologists and sociologists see overpopulation as a serious threat to the quality of human life.[108][109] Some deep ecologists, such as the radical thinker and polemicist Pentti Linkola, see human overpopulation as a threat to the entire biosphere.[110]

The effects of overpopulation are compounded by overconsumption. According to Paul R. Ehrlich:

Rich western countries are now siphoning up the planet's resources and destroying its ecosystems at an unprecedented rate. We want to build highways across the Serengeti to get more rare earth minerals for our cellphones. We grab all the fish from the sea, wreck the coral reefs and put carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. We have triggered a major extinction event ... A world population of around a billion would have an overall pro-life effect. This could be supported for many millennia and sustain many more human lives in the long term compared with our current uncontrolled growth and prospect of sudden collapse ... If everyone consumed resources at the US level – which is what the world aspires to – you will need another four or five Earths. We are wrecking our planet's life support systems.[111]

However, Ehrlich's earlier predictions were controversial. In 1968 he wrote a book The Population Bomb, in which he famously stated that "[i]n the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now."[112]

Some economists, such as Thomas Sowell[113] and Walter E. Williams[114] argue that third world poverty and famine are caused in part by bad government and bad economic policies.

Some problems associated with or exacerbated by human overpopulation and over-consumption are presented in the sections below.

Poverty, and infant and child mortality

The United Nations indicates that about 850 million people are malnourished or starving,[115] and 1.1 billion people do not have access to safe drinking water.[116] Since 1980, the global economy has grown by 380 percent, but the number of people living on less than 5 US dollars a day increased by more than 1.1 billion.[117]

Youth unemployment is also soaring, with the economy unable to absorb the spiraling numbers of those seeking to enter the work force. Many young people do not have the skills to match the needs of the Egyptian market, and the economy is small, weak and insufficiently industrialized... Instead of being something productive, the population growth is a barrel of explosives.

— — Ofir Winter, an Egypt specialist at the Institute for National Security Studies[118]

The UN Human Development Report of 1997 states: "During the last 15–20 years, more than 100 developing countries, and several Eastern European countries, have suffered from disastrous growth failures. The reductions in standard of living have been deeper and more long-lasting than what was seen in the industrialised countries during the depression in the 1930s. As a result, the income for more than one billion people has fallen below the level that was reached 10, 20 or 30 years ago". Similarly, although the proportion of "starving" people in sub-Saharan Africa has decreased, the absolute number of starving people has increased due to population growth. The percentage dropped from 38% in 1970 to 33% in 1996 and was expected to be 30% by 2010.[119] But the region's population roughly doubled between 1970 and 1996. To keep the numbers of starving constant, the percentage would have dropped by more than half.[120][121]

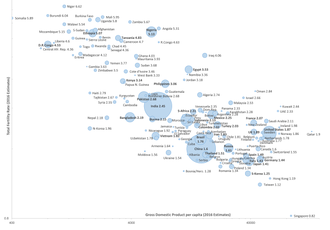

As of 2004, there were 108 countries in the world with more than five million people. All of these in which women have, on the average, more than 4 children in their lifetime, have a per capita GDP of less than $5,000. Only in two countries with per capita GDP above ~$15,000 do women have, on the average, more than 2 children in their lifetime: these are Israel and Saudi Arabia, with average lifetime births per woman between 2 and 4.

High rates of infant mortality are associated with poverty. Rich countries with high population densities have low rates of infant mortality.[125][126] However, both global poverty and infant mortality has declined over the last 200 years of population growth.[45][46]

Environmental impacts

You know, when we first set up WWF, our objective was to save endangered species from extinction. But we have failed completely; we haven't managed to save a single one. If only we had put all that money into condoms, we might have done some good.

— Sir Peter Scott (1909–1989), Founder of the World Wide Fund for Nature, Cosmos Magazine, 2010.[127]

All of our environmental problems become easier to solve with fewer people, and harder – and ultimately impossible – to solve with ever more people.

Overpopulation has substantially adversely impacted the environment of Earth starting at least as early as the 20th century.[109] According to the Global Footprint Network, "today humanity uses the equivalent of 1.5 planets to provide the resources we use and absorb our waste".[129] There are also economic consequences of this environmental degradation in the form of ecosystem services attrition.[130] Beyond the scientifically verifiable harm to the environment, some assert the moral right of other species to simply exist rather than become extinct. Environmental author Jeremy Rifkin has said that "our burgeoning population and urban way of life have been purchased at the expense of vast ecosystems and habitats. ... It's no accident that as we celebrate the urbanization of the world, we are quickly approaching another historic watershed: the disappearance of the wild."[131]

Says Peter Raven, former President of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) in their seminal work AAAS Atlas of Population & Environment, "Where do we stand in our efforts to achieve a sustainable world? Clearly, the past half century has been a traumatic one, as the collective impact of human numbers, affluence (consumption per individual) and our choices of technology continue to exploit rapidly an increasing proportion of the world's resources at an unsustainable rate. ... During a remarkably short period of time, we have lost a quarter of the world's topsoil and a fifth of its agricultural land, altered the composition of the atmosphere profoundly, and destroyed a major proportion of our forests and other natural habitats without replacing them. Worst of all, we have driven the rate of biological extinction, the permanent loss of species, up several hundred times beyond its historical levels, and are threatened with the loss of a majority of all species by the end of the 21st century."

Further, even in countries which have both large population growth and major ecological problems, it is not necessarily true that curbing the population growth will make a major contribution towards resolving all environmental problems.[132] However, as developing countries with high populations become more industrialized, pollution and consumption will invariably increase.

The Worldwatch Institute said in 2006 that the booming economies of China and India are "planetary powers that are shaping the global biosphere". The report states:

The world's ecological capacity is simply insufficient to satisfy the ambitions of China, India, Japan, Europe and the United States as well as the aspirations of the rest of the world in a sustainable way.[133]

According to Worldwatch Institute, if China and India were to consume as much resources per capita as the United States, in 2030 they would each require a full planet Earth to meet their needs.[134] In the long term these effects can lead to increased conflict over dwindling resources[135] and in the worst case a Malthusian catastrophe.

Many studies link population growth with emissions and the effect of climate change.[136][137] The global consumption of meat is projected to rise by as much as 76% by 2050 as the global population surges to more than 9 billion, resulting in further biodiversity loss and increased GHG emissions.[138][139]

Biodiversity loss and the Holocene extinction

—Chris Hedges, 2009[142]

Human overpopulation, continued population growth, and overconsumption are the primary drivers of biodiversity loss and the 6th (and ongoing) mass species extinction.[143][144][145][146][147] Present extinction rates may be as high as 140,000 species lost per year due to human activity, such as slash-and-burn techniques that sometimes are practiced by shifting cultivators, especially in countries with rapidly expanding rural populations, which have reduced habitat in tropical forests.[148] As of February 2011, the IUCN Red List lists a total of 801 animal species having gone extinct during recorded human history,[149] although the vast majority of extinctions are thought to be undocumented.[148] Biodiversity would continue to grow at an exponential rate if not for human influence.[150] Sir David King, former chief scientific adviser to the UK government, told a parliamentary inquiry: "It is self-evident that the massive growth in the human population through the 20th century has had more impact on biodiversity than any other single factor."[151][152] Paul and Anne Ehrlich said population growth is one of the main drivers of the Earth's extinction crisis.[153] The Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, released by IPBES in 2019, says that human population growth is a significant factor in biodiversity loss.[154] The report asserts that expanding human land use for agriculture and overfishing are the main causes of this decline.[155]

Both animal and plant species are affected, by habitat destruction and habitat fragmentation.

Pollution

Population growth increases levels of air pollution, water pollution, soil contamination and noise pollution.

Air pollution is causing changes in atmospheric composition and consequent global warming[156][157][158] and ocean acidification.

Potential ecological collapse

Ecological collapse refers to a situation where an ecosystem suffers a drastic, possibly permanent, reduction in carrying capacity for all organisms, often resulting in mass extinction. Usually, an ecological collapse is precipitated by a disastrous event occurring on a short time scale. Ecological collapse can be considered as a consequence of ecosystem collapse on the biotic elements that depended on the original ecosystem.[159][160]

The ocean is in great danger of collapse. In a study of 154 different marine fish species, David Byler came to the conclusion that many factors such as overfishing, climate change, and fast growth of fish populations will cause ecosystem collapse.[161] When humans fish, they usually will fish the populations of the higher trophic levels such as salmon and tuna. The depletion of these trophic levels allow the lower trophic level to overpopulate, or populate very rapidly. For example, when the population of catfish is depleting due to overfishing, plankton will then overpopulate because their natural predator is being killed off. This causes an issue called eutrophication. Since the population all consumes oxygen the dissolved oxygen (DO) levels will plummet. The DO levels dropping will cause all the species in that area to have to leave, or they will suffocate. This along with climate change, and ocean acidification can cause the collapse of an ecosystem.

Depletion and destruction of resources

Further environmental impacts that overpopulation may cause include depletion of natural resources, especially fossil fuels.[162] Overpopulation does not depend only on the size or density of the population, but on the ratio of population to available sustainable resources. It also depends on how resources are managed and distributed throughout the population.

The resources to be considered when evaluating whether an ecological niche is overpopulated include clean water, clean air, food, shelter, warmth, and other resources necessary to sustain life. If the quality of human life is addressed, there may be additional resources considered, such as medical care, education, proper sewage treatment, waste disposal and energy supplies. Overpopulation places competitive stress on the basic life sustaining resources,[163] leading to a diminished quality of life.[109]

Directly related to maintaining the health of the human population is water supply, and it is one of the resources that experience the biggest strain. With the global population at about 7.5 billion, and each human theoretically needing 2 liters of drinking water, there is a demand for 15 billion liters of water each day to meet the minimum requirement for healthy living (United). Weather patterns, elevation, and climate all contribute to uneven distribution of fresh drinking water. Without clean water, good health is not a viable option. Besides drinking, water is used to create sanitary living conditions and is the basis of creating a healthy environment fit to hold human life. In addition to drinking water, water is also used for bathing, washing clothes and dishes, flushing toilets, a variety of cleaning methods, recreation, watering lawns, and farm irrigation. Irrigation poses one of the largest problems, because without sufficient water to irrigate crops, the crops die and then there is the problem of food rations and starvation. In addition to water needed for crops and food, there is limited land area dedicated to food production, and not much more that is suitable to be added. Arable land, needed to sustain the growing population, is also a factor because land being under or over cultivated easily upsets the delicate balance of nutrition supply. There are also problems with location of arable land with regard to proximity to countries and relative population (Bashford 240). Access to nutrition is an important limiting factor in population sustainability and growth. No increase in arable land added to the still increasing human population will eventually pose a serious conflict. Only 38% of the land area of the globe is dedicated to agriculture, and there is not room for much more. Although plants produce 54 billion metric tons of carbohydrates per year, when the population is expected to grow to 9 billion by 2050, the plants may not be able to keep up (Biello). Food supply is a primary example of how a resource reacts when its carrying capacity is exceeded. By trying to grow more and more crops off of the same amount of land, the soil becomes exhausted. Because the soil is exhausted, it is then unable to produce the same amount of food as before, and is overall less productive. Therefore, by using resources beyond a sustainable level, the resource become nullified and ineffective, which further increases the disparity between the demand for a resource and the availability of a resource. There must be a shift to provide adequate recovery time to each one of the supplies in demand to support contemporary human lifestyles. [164][165][166]

David Pimentel has stated that "With the imbalance growing between population numbers and vital life sustaining resources, humans must actively conserve cropland, freshwater, energy, and biological resources. There is a need to develop renewable energy resources. Humans everywhere must understand that rapid population growth damages the Earth's resources and diminishes human well-being."[167][168]

These reflect the comments also of the United States Geological Survey in their paper "The Future of Planet Earth: Scientific Challenges in the Coming Century": "As the global population continues to grow...people will place greater and greater demands on the resources of our planet, including mineral and energy resources, open space, water, and plant and animal resources." "Earth's natural wealth: an audit" by New Scientist magazine states that many of the minerals that we use for a variety of products are in danger of running out in the near future.[169] A handful of geologists around the world have calculated the costs of new technologies in terms of the materials they use and the implications of their spreading to the developing world. All agree that the planet's booming population and rising standards of living are set to put unprecedented demands on the materials that only Earth itself can provide.[169] Limitations on how much of these materials is available could even mean that some technologies are not worth pursuing long term.... "Virgin stocks of several metals appear inadequate to sustain the modern 'developed world' quality of life for all of Earth's people under contemporary technology".[170]

On the other hand, some cornucopian researchers, such as Julian L. Simon and Bjørn Lomborg believe that resources exist for further population growth. In a 2010 study, they concluded that "there are not (and will never be) too many people for the planet to feed" according to The Independent.[171] Some critics warn, this will be at a high cost to the Earth: "the technological optimists are probably correct in claiming that overall world food production can be increased substantially over the next few decades...[however] the environmental cost of what Paul R. and Anne H. Ehrlich describe as 'turning the Earth into a giant human feedlot' could be severe. A large expansion of agriculture to provide growing populations with improved diets is likely to lead to further deforestation, loss of species, soil erosion, and pollution from pesticides and fertilizer runoff as farming intensifies and new land is brought into production."[172] Since we are intimately dependent upon the living systems of the Earth,[173][174][175] some scientists have questioned the wisdom of further expansion.

According to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, a four-year research effort by 1,360 of the world's prominent scientists commissioned to measure the actual value of natural resources to humans and the world, "The structure of the world's ecosystems changed more rapidly in the second half of the twentieth century than at any time in recorded human history, and virtually all of Earth's ecosystems have now been significantly transformed through human actions."[176] "Ecosystem services, particularly food production, timber and fisheries, are important for employment and economic activity. Intensive use of ecosystems often produces the greatest short-term advantage, but excessive and unsustainable use can lead to losses in the long term. A country could cut its forests and deplete its fisheries, and this would show only as a positive gain to GDP, despite the loss of capital assets. If the full economic value of ecosystems were taken into account in decision-making, their degradation could be significantly slowed down or even reversed."[120][177]

Another study was done by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) called the Global Environment Outlook.

Although all resources, whether mineral or other, are limited on the planet, there is a degree of self-correction whenever a scarcity or high-demand for a particular kind is experienced. For example, in 1990 known reserves of many natural resources were higher, and their prices lower, than in 1970, despite higher demand and higher consumption. Whenever a price spike would occur, the market tended to correct itself whether by substituting an equivalent resource or switching to a new technology.[178]

Fresh water

Overpopulation may lead to inadequate fresh water[116] for drinking as well as sewage treatment and effluent discharge. Some countries, like Saudi Arabia, use energy-expensive desalination to solve the problem of water shortages.[179][180]

Fresh water supplies, on which agriculture depends, are running low worldwide.[181][182] This water crisis is only expected to worsen as the population increases.[183]

Potential problems with dependence on desalination are reviewed below, however, the majority of the world's freshwater supply is contained in the polar icecaps, and underground river systems accessible through springs and wells.

Fresh water can be obtained from salt water by desalination. For example, Malta derives two-thirds of its freshwater by desalination. A number of nuclear powered desalination plants exist;[184][185] however, the high costs of desalination, especially for poor countries, makes the transport of large amounts of desalinated seawater to interiors of large countries impractical.[186] The cost of desalination varies; Israel is now desalinating water for a cost of 53 cents per cubic meter,[179] Singapore at 49 cents per cubic meter.[187] In the United States, the cost is 81 cents per cubic meter ($3.06 for 1,000 gallons).[188]

According to a 2004 study by Zhou and Tol, "one needs to lift the water by 2000 m, or transport it over more than 1600 km to get transport costs equal to the desalination costs. Desalinated water is expensive in places that are both somewhat far from the sea and somewhat high, such as Riyadh and Harare. In other places, the dominant cost is desalination, not transport. This leads to somewhat lower costs in places like Beijing, Bangkok, Zaragoza, Phoenix, and, of course, coastal cities like Tripoli." Thus while the study is generally positive about the technology for affluent areas that are proximate to oceans, it concludes that "Desalinated water may be a solution for some water-stress regions, but not for places that are poor, deep in the interior of a continent, or at high elevation. Unfortunately, that includes some of the places with biggest water problems."[189] "Another potential problem with desalination is the byproduction of saline brine, which can be a major cause of marine pollution when dumped back into the oceans at high temperatures."[189]

The world's largest desalination plant is the Jebel Ali Desalination Plant (Phase 2) in the United Arab Emirates, which can produce 300 million cubic metres of water per year,[190] or about 2500 gallons per second. The largest desalination plant in the US is the one at Tampa Bay, Florida, which began desalinating 25 million gallons (95000 m3) of water per day in December 2007. A 17 January 2008, article in the Wall Street Journal states, "Worldwide, 13,080 desalination plants produce more than 12 billion gallons of water a day, according to the International Desalination Association."[191] After being desalinated at Jubail, Saudi Arabia, water is pumped 200 miles (320 km) inland though a pipeline to the capital city of Riyadh.[192]

However, new data originating from the GRACE experiments and isotopic testing done by the IAEA show that the Nubian aquifer—which is under the largest, driest part of the earth's surface, has enough water in it to provide for "at least several centuries". In addition to this, new and highly detailed maps of the earth's underground reservoirs will be soon created from these technologies that will further allow proper budgeting of cheap water.[193]

Water deficits

Water deficits, which are already spurring heavy grain imports in numerous smaller countries, may soon do the same in larger countries, such as China or India, if technology is not used.[194] The water tables are falling in scores of countries (including Northern China, the US, and India) owing to widespread overdrafting beyond sustainable yields. Other countries affected include Pakistan, Iran, and Mexico. This overdrafting is already leading to water scarcity and cutbacks in grain harvest. Even with the overpumping of its aquifers, China has developed a grain deficit. This effect has contributed in driving grain prices upward. Most of the 3 billion people projected to be added worldwide by mid-century will be born in countries already experiencing water shortages. Desalination is also considered a viable and effective solution to the problem of water shortages.[179][187]

Overpopulation together with water deficits could trigger regional tensions, including warfare.[195]

Land

The World Resources Institute states that "Agricultural conversion to croplands and managed pastures has affected some 3.3 billion [hectares] – roughly 26 percent of the land area. All totaled, agriculture has displaced one-third of temperate and tropical forests and one-quarter of natural grasslands."[196][197] Forty percent of the land area is under conversion and fragmented; less than one quarter, primarily in the Arctic and the deserts, remains intact.[198] Usable land may become less useful through salinization, deforestation, desertification, erosion, and urban sprawl. Global warming may cause flooding of many of the most productive agricultural areas.[199] The development of energy sources may also require large areas, for example, the building of hydroelectric dams. Thus, available useful land may become a limiting factor. By most estimates, at least half of cultivable land is already being farmed, and there are concerns that the remaining reserves are greatly overestimated.[200]

High crop yield vegetables like potatoes and lettuce use less space on inedible plant parts, like stalks, husks, vines, and inedible leaves. New varieties of selectively bred and hybrid plants have larger edible parts (fruit, vegetable, grain) and smaller inedible parts; however, many of these gains of agricultural technology are now historic, and new advances are more difficult to achieve. With new technologies, it is possible to grow crops on some marginal land under certain conditions. Aquaculture could theoretically increase available area. Hydroponics and food from bacteria and fungi, like quorn, may allow the growing of food without having to consider land quality, climate, or even available sunlight, although such a process may be very energy-intensive. Some argue that not all arable land will remain productive if used for agriculture because some marginal land can only be made to produce food by unsustainable practices like slash-and-burn agriculture. Even with the modern techniques of agriculture, the sustainability of production is in question.

Some countries, such as the United Arab Emirates and particularly the Emirate of Dubai have constructed large artificial islands, or have created large dam and dike systems, like the Netherlands, which reclaim land from the sea to increase their total land area.[201][202] Some scientists have said that in the future, densely populated cities will use vertical farming to grow food inside skyscrapers.[203] The notion that space is limited has been decried by skeptics, who point out that the Earth's population of roughly 6.8 billion people could comfortably be housed an area comparable in size to the state of Texas, in the United States (about 269,000 square miles or 696,706.80 square kilometres).[204] However, the impact of humanity extends over a far greater area than that required simply for housing.

Fossil fuels

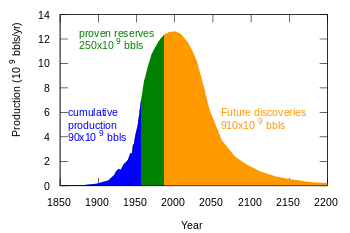

Population optimists have been criticized for failing to take into account the depletion of fossil fuels required for the production of fertilizers, tillage, transportation, etc.[205] In his 1992 book Earth in the Balance, Al Gore wrote, "... it ought to be possible to establish a coordinated global program to accomplish the strategic goal of completely eliminating the internal combustion engine over, say, a twenty-five-year period..."[206] Approximately half of the oil produced in the United States is refined into gasoline for use in internal combustion engines.[207]

The report Peaking of World Oil Production: Impacts, Mitigation, and Risk Management, commonly referred to as the Hirsch report, was created by request for the US Department of Energy and published in February 2005.[208] Some information was updated in 2007.[209] It examined the time frame for the occurrence of peak oil, the necessary mitigating actions, and the likely impacts based on the timeliness of those actions. It concludes that world oil peaking is going to happen, and will likely be abrupt. Initiating a mitigation crash program 20 years before peaking appears to offer the possibility of avoiding a world liquid fuels shortfall for the forecast period.

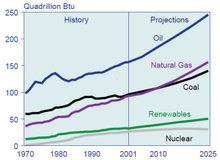

Optimists counter that fossil fuels will be sufficient until the development and implementation of suitable replacement technologies—such as nuclear power or various sources of renewable energy—occurs.[210] Methods of manufacturing fertilizers from garbage, sewage, and agricultural waste by using thermal depolymerization have been discovered.[211][212]

With increasing awareness about global warming, the question of peak oil has become less relevant. According to many studies, about 80% of the remaining fossil fuels must be left untouched because the bottleneck has shifted from resource availability to the resource of absorbing the generated greenhouse gases when burning fossil fuels.[213]

Food

Some scientists argue that there is enough food to support the world population,[214][215] and some dispute this, particularly if sustainability is taken into account.[216]

Many countries rely heavily on imports. Egypt and Iran rely on imports for 40% of their grain supply. Yemen and Israel import more than 90%. And just 6 countries – Argentina, Australia, Canada, France, Thailand and the USA – supply 90% of grain exports. In recent decades the US alone supplied almost half of world grain exports.[217]

A 2001 United Nations report says population growth is "the main force driving increases in agricultural demand" but "most recent expert assessments are cautiously optimistic about the ability of global food production to keep up with demand for the foreseeable future (that is to say, until approximately 2030 or 2050)", assuming declining population growth rates.[218]

However, the observed figures for 2016 show an actual increase in absolute numbers of undernourished people in the world, 815 million in 2016 versus 777 million in 2015.[219] The FAO estimates that these numbers are still far lower than the nearly 900 million registered in 2000.[219]

Global perspective on food supply

The amounts of natural resources in this context are not necessarily fixed, and their distribution is not necessarily a zero-sum game. For example, due to the Green Revolution and the fact that more and more land is appropriated each year from wild lands for agricultural purposes, the worldwide production of food had steadily increased up until 1995. World food production per person was considerably higher in 2005 than 1961.

As world population doubled from 3 to 6 billion, daily calorie consumption in poor countries increased from 1,932 to 2,650, and the percentage of people in those countries who were malnourished fell from 45% to 18%. This suggests that Third World poverty and famine are caused by underdevelopment, not overpopulation.[220] However, others question these statistics.[119] From 1950 to 1984, as the Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the world, grain production increased by over 250%.[221] The world population has grown by about four billion since the beginning of the Green Revolution and most believe that, without the Revolution, there would be greater famine and malnutrition than the UN presently documents.[68][222]

The number of people who are overweight has surpassed the number who are undernourished. In a 2006 news story, MSNBC reported, "There are an estimated 800 million undernourished people and more than a billion considered overweight worldwide." The U.S. has one of the highest rates of obesity in the world.[223] However, studies show that wealthy and educated people are far likelier to eat healthy food,[224] indicating obesity is a disease related to poverty and lack of education and excessive advertising of unhealthy eatables at cheaper cost, high in calories, with little nutritive value are consumed.[225][226]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations states in its report The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2018 that the new data indicates an increase of hunger in the world, reversing the recent trend. It is estimated that in 2017 the number of undernourished people increased to 821 million, around 11 per cent of the world population. The FAO states: "Evidence shows that, for many countries, recent increases in hunger are associated with extreme climate events, especially where there is both high exposure to climate extremes and high vulnerability related to agriculture and livelihood systems."[219]

As of 2008, the price of grain has increased due to more farming used in biofuels,[227] world oil prices at over $100 a barrel,[228] global population growth,[229] climate change,[230] loss of agricultural land to residential and industrial development,[231][232] and growing consumer demand in China and India[233][234] Food riots have recently taken place in many countries across the world.[235][236][237] An epidemic of stem rust on wheat caused by race Ug99 is currently spreading across Africa and into Asia and is causing major concern. A virulent wheat disease could destroy most of the world's main wheat crops, leaving millions to starve. The fungus has spread from Africa to Iran, and may already be in Afghanistan and Pakistan.[238][239][240]

Food security will become more difficult to achieve as resources run out. Resources in danger of becoming depleted include oil, phosphorus, grain, fish, and water.[241][242] The British scientist John Beddington predicted in 2009 that supplies of energy, food, and water will need to be increased by 50% to reach demand levels of 2030.[243][244] According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), food supplies will need to be increased by 70% by 2050 to meet projected demands.[245]

Africa

The Population Reference Bureau in the US reported that the population of Sub-Saharan Africa – the poorest region in the continent – is rising faster than most of the rest of the world, and that "Rapid population growth makes it difficult for economies to create enough jobs to lift large numbers of people out of poverty." Seven of the 10 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa with the highest fertility rates also appear among the bottom 10 listed on the United Nations' Human Development Index.[246]

Hunger and malnutrition kill nearly 6 million children a year, and more people are malnourished in sub-Saharan Africa this decade than in the 1990s, according to a report released by the Food and Agriculture Organization. In sub-Saharan Africa, the number of malnourished people grew to 203.5 million people in 2000–02 from 170.4 million 10 years earlier says The State of Food Insecurity in the World report. In 2001, 46.4% of people in sub-Saharan Africa were living in extreme poverty.[247]

Asia

| External video | |

|---|---|

According to a 2004 article from the BBC, China, the world's most populous country, suffers from an "obesity surge". The article stated that, "Altogether, around 200 million people are thought to be overweight, 22.8% of the population, and 60 million (7.1%) obese".[248] More recent data indicate China's grain production peaked in the mid-1990s, due to increased extraction of groundwater in the North China Plain.[249]

Japan

Japan may face a food crisis that could reduce daily diets to the austere meals of the 1950s, believes a senior government adviser.[250]

Warfare and conflict over dwindling resources

Overpopulation causes crowding, and conflict over scarce resources, which in turn lead to increased levels of warfare.[251] It has been suggested[252] that overpopulation leads to increased levels of tensions both between and within countries. Modern usage of the term "lebensraum" supports the idea that overpopulation may promote warfare through fear of resource scarcity and increasing numbers of youth lacking the opportunity to engage in peaceful employment (the youth bulge theory).

Criticism of this hypothesis

The hypothesis that population pressure causes increased warfare has been recently criticized on statistical grounds. Two studies focusing on specific historical societies and analyses of cross-cultural data have failed to find positive correlation between population density and incidence of warfare. Andrey Korotayev, in collaboration with Peter Turchin, has shown that such negative results do not falsify the population-warfare hypothesis.[253]

Population and warfare are dynamical variables, and if their interaction causes sustained oscillations, then we do not in general expect to find strong correlation between the two variables measured at the same time (that is, unlagged). Korotayev and Turchin have explored mathematically what the dynamical patterns of interaction between population and warfare (focusing on internal warfare) might be in both stateless and state societies. Next, they have tested the model predictions in several empirical case studies: early modern England, Han and Tang China, and the Roman Empire. Their empirical results have supported the population-warfare theory: that there is a tendency for population numbers and internal warfare intensity to oscillate with the same period but shifted in phase (with warfare peaks following population peaks).

Furthermore, they have demonstrated that in the agrarian societies the rates of change of the two variables behave precisely as predicted by the theory: population rate of change is negatively affected by warfare intensity, while warfare rate of change is positively affected by population density.[253][254][255]

Other

- Loss of arable land and increase in desertification.[256] Deforestation and desertification can be reversed by adopting property rights, and this policy is successful even while the human population continues to grow.[257]

- Intensive factory farming to support large populations. It results in human threats including the evolution and spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria diseases, excessive air and water pollution, and new viruses that infect humans.[258][259][260][261]

- Increased chance of the emergence of new epidemics and pandemics.[262] For many environmental and social reasons, including overcrowded living conditions, malnutrition and inadequate, inaccessible, or non-existent health care, the poor are more likely to be exposed to infectious diseases.[263]

- Starvation, malnutrition[115] or poor diet with ill health and diet-deficiency diseases (e.g. rickets). However, rich countries with high population densities do not have famine.[114]

- Low life expectancy in countries with fastest growing populations.[264] Overall life expectancy has increased globally despite of population growth, including countries with fast-growing populations.[45]

- Unhygienic living conditions for many based upon water resource depletion, discharge of raw sewage[265] and solid waste disposal. However, this problem can be reduced with the adoption of sewers. For example, after Karachi, Pakistan installed sewers, its infant mortality rate fell substantially.[266]

- Elevated crime rate due to drug cartels and increased theft by people stealing resources to survive.[267]

- Less personal freedom and more restrictive laws. Laws regulate and shape politics, economics, history and society and serve as a mediator of relations and interactions between people. The higher the population density, the more frequent such interactions become, and thus there develops a need for more laws and/or more restrictive laws to regulate these interactions and relations. It was speculated by Aldous Huxley in 1958 that democracy is threatened by overpopulation, and could give rise to totalitarian style governments.[268] However, over the last 200 years of population growth, the actual level of personal freedom has increased rather than declined.[45]

Further dynamics

| External video | |

|---|---|

Demographic transition

.png)

The theory of demographic transition held that, after the standard of living and life expectancy increase, family sizes and birth rates decline. However, as new data has become available, it has been observed that after a certain level of development (HDI equal to 0.86 or higher) the fertility increases again and is often represented as a "J" shape.[269] This means that both the worry that the theory generated about aging populations and the complacency it bred regarding the future environmental impact of population growth could need reevaluation.

Factors cited in the old theory included such social factors as later ages of marriage, the growing desire of many women in such settings to seek careers outside child rearing and domestic work, and the decreased need for children in industrialized settings. The latter factor stems from the fact that children perform a great deal of work in small-scale agricultural societies, and work less in industrial ones; it has been cited to explain the decline in birth rates in industrializing regions.

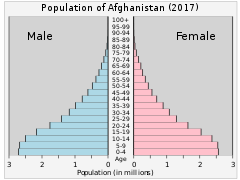

Many countries have high population growth rates but lower total fertility rates because high population growth in the past skewed the age demographic toward a young age, so the population still rises as the more numerous younger generation approaches maturity. "Demographic entrapment" is a concept developed by Maurice King, Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Leeds, who posits that this phenomenon occurs when a country has a population larger than its carrying capacity, no possibility of migration, and exports too little to be able to import food. This will cause starvation. He claims that for example many sub-Saharan nations are or will become stuck in demographic entrapment, instead of having a demographic transition.[270]

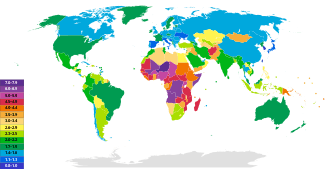

For the world as a whole, the number of children born per woman decreased from 5.02 to 2.65 between 1950 and 2005. A breakdown by region is as follows:

- Europe – 2.66 to 1.41

- North America – 3.47 to 1.99

- Oceania – 3.87 to 2.30

- Central America – 6.38 to 2.66

- South America – 5.75 to 2.49

- Asia (excluding Middle East) – 5.85 to 2.43

- Middle East & North Africa – 6.99 to 3.37

- Sub-Saharan Africa – 6.7 to 5.53

Excluding the theoretical reversal in fertility decrease for high development, the projected world number of children born per woman for 2050 would be around 2.05. Only the Middle East & North Africa (2.09) and Sub-Saharan Africa (2.61) would then have numbers greater than 2.05.[271]

Carrying capacity

.jpg)

Many studies have tried to estimate the world's carrying capacity for humans, that is, the maximum population the world can host.[272] A meta-analysis of 69 such studies from 1694 until 2001 found the average predicted maximum number of people the Earth would ever have was 7.7 billion people, with lower and upper meta-bounds at 0.65 and 98 billion people, respectively. They conclude: "recent predictions of stabilized world population levels for 2050 exceed several of our meta-estimates of a world population limit".[273] A 2001 UN report said that two-thirds of the predictions fall in the range of 4 to 16 billion with unspecified standard errors, with a median of about 10 billion.[132]

Maximum sustainable human population

Some groups (for example, the World Wide Fund for Nature[274][275] and Global Footprint Network) have stated that the yearly biocapacity of Earth is being exceeded as measured using the ecological footprint. In 2006, WWF's "Living Planet Report" stated that in order for all humans to live with the current consumption patterns of Europeans, we would be spending three times more than what the planet can renew.[276] Humanity as a whole was using, by 2006, 40 percent more than what Earth can regenerate.[277] However, Roger Martin of Population Matters states the view: "the poor want to get rich, and I want them to get rich," with a later addition, "of course we have to change consumption habits,... but we've also got to stabilise our numbers".[278] Another study by the World Wildlife Fund in 2014 found that it would take the equivalent of 1.5 Earths of biocapacity to meet humanity's current levels of consumption.[279]

But critics question the simplifications and statistical methods used in calculating ecological footprints. Therefore Global Footprint Network and its partner organizations have engaged with national governments and international agencies to test the results – reviews have been produced by France, Germany, the European Commission, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Japan and the United Arab Emirates.[280] Some point out that a more refined method of assessing Ecological Footprint is to designate sustainable versus non-sustainable categories of consumption.[281][282]

Jade Sasser believes that calculating a maximum of number of humanity which may be allowed to live while only some, mostly privileged European former colonial powers, are mostly responsible for unsustainably using up the Earth is wrong.[283]

In a 1994 study titled Food, Land, Population and the U.S. Economy, David Pimentel and Mario Giampietro estimated the maximum U.S. population for a sustainable economy at 200 million.[284] And in order to achieve a sustainable economy and avert disaster, the United States would have to reduce its population by at least one-third, and world population would have to be reduced by two-thirds.[285]

Paul R. Ehrlich stated in 2018 that the optimum size of the global human population is between 1.5 and 2 billion.[286]

Projections of population growth

| Continent | Projected 2050 population[287] |

|---|---|

| Africa | 2.5 billion |

| Asia | 5.5 billion |

| Europe | 716 million |

| Latin America and Caribbean | 780 million |

| North America | 435 million |

According to projections, the world population will continue to grow until at least 2050, with the population reaching 9 billion in 2040,[288][289] and some predictions putting the population as high as 11 billion in 2050.[290] The median estimate for future growth sees the world population reaching 8.6 billion in 2030, 9.8 billion in 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100[291] assuming a continuing decrease in average fertility rate from 2.5 births per woman in 2010–2015 to 2.2 in 2045–2050 and to 2.0 in 2095–2100, according to the medium-variant projection.[291] Walter Greiling projected in the 1950s that world population would reach a peak of about nine billion, in the 21st century, and then stop growing, after a readjustment of the Third World and a sanitation of the tropics.[292]

In 2000, the United Nations estimated that the world's population was growing at the rate of 1.14% (or about 75 million people) per year and according to data from the CIA's World Factbook, the world human population currently increases by 145 every minute.[293]

According to the United Nations' World Population Prospects report:[294]

- The world population is currently growing by approximately 74 million people per year. Current United Nations predictions estimate that the world population will reach 9.0 billion around 2050, assuming a decrease in average fertility rate from 2.5 down to 2.0.[295][296]

- Almost all growth will take place in the less developed regions, where today's 5.3 billion population of underdeveloped countries is expected to increase to 7.8 billion in 2050. By contrast, the population of the more developed regions will remain mostly unchanged, at 1.2 billion. An exception is the United States population, which is expected to increase by 44% from 2008 to 2050.[297]

- In 2000–2005, the average world fertility was 2.65 children per woman, about half the level in 1950–1955 (5 children per woman). In the medium variant, global fertility is projected to decline further to 2.05 children per woman.

- During 2005–2050, nine countries are expected to account for half of the world's projected population increase: India, Pakistan,[298] Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Bangladesh, Uganda, United States, Ethiopia, and China, listed according to the size of their contribution to population growth. China would be higher still in this list were it not for its one-child policy.

- Global life expectancy at birth is expected to continue rising from 65 years in 2000–2005 to 75 years in 2045–2050. In the more developed regions, the projection is to 82 years by 2050. Among the least developed countries, where life expectancy today is just under 50 years, it is expected to increase to 66 years by 2045–2050.

- The population of 51 countries or areas is expected to be lower in 2050 than in 2005.

- During 2005–2050, the net number of international migrants to more developed regions is projected to be 98 million. Because deaths are projected to exceed births in the more developed regions by 73 million during 2005–2050, population growth in those regions will largely be due to international migration.

- In 2000–2005, net migration in 28 countries either prevented population decline or doubled at least the contribution of natural increase (births minus deaths) to population growth.

- Birth rates are now falling in a small percentage of developing countries, while the actual populations in many developed countries would fall without immigration.[295]

Urban growth

In 1800 only 3% of the world's population lived in cities. By the 20th century's close, 47% did so. In 1950 there were 83 cities with populations exceeding one million; but by 2007 this had risen to 468 "agglomerations".[299] If the trend continues, the world's urban population will double every 38 years. In 2007 UN forecasted that urban population would rise to three out of five or 60% by 2030 and an increase in urban population from 3.2 billion to nearly 5 billion by 2030.[300] As of 2018 55% live in cities and UN predicts that it will be 68% by 2050.[301]

| Year | 1800 | 2000 | 2018 | 2050 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % City | 3% | 47% | 55% | *68% |

The increase will be most dramatic in the poorest and least-urbanised continents, Asia and Africa. Projections indicate that most urban growth over the next 25 years will be in developing countries.[302] One billion people, one-seventh of the world's population, or one-third of urban population, now live in shanty towns,[303] which are seen as "breeding grounds" for social problems such as unemployment, poverty, crime, drug addiction, alcoholism, and other social ills. In many poor countries, slums exhibit high rates of disease due to unsanitary conditions, malnutrition, and lack of basic health care.[304]

In 2000, there were 18 megacities – conurbations such as Tokyo, Beijing, Guangzhou, Seoul, Karachi, Mexico City, Mumbai, São Paulo, London and New York City – that have populations in excess of 10 million inhabitants.[305] Greater Tokyo already has 38 million, more than the entire population of Canada (at 36.7 million).

According to the Far Eastern Economic Review, Asia alone will have at least 10 'hypercities' by 2025, that is, cities inhabited by more than 19 million people, including Jakarta (24.9 million people), Dhaka (25 million), Karachi (26.5 million), Shanghai (27 million) and Mumbai (27 million).[306] Lagos has grown from 300,000 in 1950 to an estimated 15 million today, and the Nigerian government estimates that city will have expanded to 25 million residents by 2015.[307] Chinese experts forecast that Chinese cities will contain 800 million people by 2020.[308]

Proposed solutions and mitigation measures

Given the current levels of violence by this culture against both humans and the natural world, however, it's not possible to speak of reductions in population and consumption that do not involve violence and privation, not because the reductions themselves would necessarily involve violence, but because violence and privation have become the default of our culture.

Several solutions and mitigation measures have the potential to reduce overpopulation. Some solutions are to be applied on a global planetary level (e.g., via UN resolutions), while some on a country or state government organization level, and some on a family or an individual level. Some of the proposed mitigations aim to help implement new social, cultural, behavioral and political norms to replace or significantly modify current norms.

For example, in societies like China, the government has put policies in place that regulate the number of children allowed to a couple. Other societies have implemented social marketing strategies in order to educate the public on overpopulation effects. "The intervention can be widespread and done at a low cost. A variety of print materials (flyers, brochures, fact sheets, stickers) needs to be produced and distributed throughout the communities such as at local places of worship, sporting events, local food markets, schools and at car parks (taxis / bus stands)."[310]

Such prompts work to introduce the problem so that new or modified social norms are easier to implement. Certain government policies are making it easier and more socially acceptable to use contraception and abortion methods. An example of a country whose laws and norms are hindering the global effort to slow population growth is Afghanistan. "The approval by Afghan President Hamid Karzai of the Shia Personal Status Law in March 2009 effectively destroyed Shia women's rights and freedoms in Afghanistan. Under this law, women have no right to deny their husbands sex unless they are ill, and can be denied food if they do."[311]

Scientists and technologists including e.g. Huesemann and Ehrlich caution that science and technology, as currently practiced, cannot solve the serious problems global human society faces, and that a cultural-social-political shift is needed to reorient science and technology in a more socially responsible and environmentally sustainable direction.[312] [313]

Reducing overpopulation

Education and empowerment

One option is to focus on education about overpopulation, family planning, and birth control methods, and to make birth-control devices like male and female condoms, contraceptive pills and intrauterine devices easily available. Worldwide, nearly 40% of pregnancies are unintended (some 80 million unintended pregnancies each year).[314] An estimated 350 million women in the poorest countries of the world either did not want their last child, do not want another child or want to space their pregnancies, but they lack access to information, affordable means and services to determine the size and spacing of their families. In the United States, in 2001, almost half of pregnancies were unintended.[315] In the developing world, some 514,000 women die annually of complications from pregnancy and abortion,[316] with 86% of these deaths occurring in the sub-Saharan Africa region and South Asia.[317] Additionally, 8 million infants die, many because of malnutrition or preventable diseases, especially from lack of access to clean drinking water.[318]

Women's rights and their reproductive rights in particular are issues regarded to have vital importance in the debate.[319]

The only ray of hope I can see – and it's not much – is that wherever women are put in control of their lives, both politically and socially, where medical facilities allow them to deal with birth control and where their husbands allow them to make those decisions, birth rate falls. Women don't want to have 12 kids of whom nine will die.

Egypt announced a program to reduce its overpopulation by family planning education and putting women in the workforce. It was announced in June 2008 by the Minister of Health and Population, and the government has set aside 480 million Egyptian pounds (about $90 million US) for the program.[321]

Several scientists (including e.g. Paul and Anne Ehrlich and Gretchen Daily) proposed that humanity should work at stabilizing its absolute numbers, as a starting point towards beginning the process of reducing the total numbers. They suggested the following solutions and policies: following a small-family-size socio-cultural-behavioral norm worldwide (especially one-child-per-family ethos), and providing contraception to all along with proper education on its use and benefits (while providing access to safe, legal abortion as a backup to contraception), combined with a significantly more equitable distribution of resources globally.[322][323] In the book "Evolution Science and Ethics in the Third Millennium", Robert Cliquet and Dragana Avramov also point out that the one (and a half)-child-per-family ethos is certainly a good one and that we should reduce the world population so that it is no larger than 1 to 3 billion.[324]

Business magnate Ted Turner proposed a "voluntary, non-imposed" one-child-per-family cultural norm. A "pledge two or fewer" campaign is run by Population Matters (a UK population concern organisation), in which people are encouraged to limit themselves to small family size.

Population planning that is intended to reduce population size or growth rate may promote or enforce one or more of the following practices, although there are other methods as well:

- Greater and better access to contraception

- Reducing infant mortality so that parents do not need to have many children to ensure at least some survive to adulthood.[325]