Indira Gandhi

Indira Priyadarshini Gandhi (Hindi: [ˈɪndɪɾaː ˈɡaːndʱiː] (![]()

Indira Gandhi | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd Prime Minister of India | |

| In office 14 January 1980 – 31 October 1984 | |

| President | N. Sanjiva Reddy Zail Singh |

| Preceded by | Charan Singh |

| Succeeded by | Rajiv Gandhi |

| In office 24 January 1966 – 24 March 1977 | |

| President | Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan Zakir Husain V. V. Giri Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed |

| Deputy | Morarji Desai |

| Preceded by | Gulzarilal Nanda (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | Morarji Desai |

| Minister of External Affairs | |

| In office 9 March 1984 – 31 October 1984 | |

| Preceded by | P. V. Narasimha Rao |

| Succeeded by | Rajiv Gandhi |

| In office 22 August 1967 – 14 March 1969 | |

| Preceded by | M. C. Chagla |

| Succeeded by | Dinesh Singh |

| Minister of Defence | |

| In office 14 January 1980 – 15 January 1982 | |

| Preceded by | Chidambaram Subramaniam |

| Succeeded by | R. Venkataraman |

| In office 30 November 1975 – 20 December 1975 | |

| Preceded by | Swaran Singh |

| Succeeded by | Bansi Lal |

| Minister of Home Affairs | |

| In office 27 June 1970 – 4 February 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Yashwantrao Chavan |

| Succeeded by | Uma Shankar Dikshit |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 17 July 1969 – 27 June 1970 | |

| Preceded by | Morarji Desai |

| Succeeded by | Yashwantrao Chavan |

| Minister of Information and Broadcasting | |

| In office 9 June 1964 – 24 January 1966 | |

| Prime Minister | Lal Bahadur Shastri |

| Preceded by | Satya Narayan Sinha |

| Succeeded by | Kodardas Kalidas Shah |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Indira Priyadarshini Nehru 19 November 1917 Allahabad, United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, British India (present-day Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, India) |

| Died | 31 October 1984 (aged 66) New Delhi, India |

Monuments | |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Relations | See Nehru–Gandhi family |

| Children | Rajiv Gandhi Sanjay Gandhi |

| Parents | Jawaharlal Nehru (Father) Kamala Nehru (Mother) |

| Alma mater | Visva-Bharati University (dropped out)[1] Somerville College, Oxford (dropped out)[1] |

| Awards | Bharat Ratna (1971) Bangladesh Freedom Honour (2011) |

| Signature | |

During Nehru's time as Prime Minister of India from 1947 to 1964, Gandhi was considered a key assistant and accompanied him on his numerous foreign trips.[4] She was elected President of the Indian National Congress in 1959. Upon her father's death in 1964, she was appointed as a member of the Rajya Sabha (upper house) and became a member of Lal Bahadur Shastri's cabinet as Minister of Information and Broadcasting.[5] In the Congress Party's parliamentary leadership election held in early 1966 (upon the death of Shastri), she defeated her rival Morarji Desai to become leader, and thus succeeded Shastri as Prime Minister of India.

As prime minister, Gandhi was known for her political intransigency and unprecedented centralisation of power. She went to war with Pakistan in support of the independence movement and war of independence in East Pakistan, which resulted in an Indian victory and the creation of Bangladesh, as well as increasing India's influence to the point where it became the sole regional power of South Asia. Citing separatist tendencies, and in response to a call for revolution, Gandhi instituted a state of emergency from 1975 to 1977 where basic civil liberties were suspended and the press was censored. Widespread atrocities were carried out during the emergency.[6] In 1980, she returned to power after free and fair elections. After Gandhi ordered military action in the Golden Temple in Operation Blue Star, her own bodyguards and Sikh nationalists assassinated her on 31 October 1984.

In 1999, Indira Gandhi was named "Woman of the Millennium" in an online poll organised by the BBC.[7] In 2020 Gandhi was named by the Time magazine among world's 100 powerful women who defined the last century.[8][9]

Early life and career

Indira Gandhi was born Indira Nehru into a Kashmiri Pandit family on 19 November 1917 in Allahabad.[10][11] Her father, Jawaharlal Nehru, was a leading figure in India's political struggle for independence from British rule, and became the first Prime Minister of the Dominion (and later Republic) of India.[12] She was the only child (a younger brother died young),[13] and grew up with her mother, Kamala Nehru, at the Anand Bhavan, a large family estate in Allahabad.[14] She had a lonely and unhappy childhood.[15] Her father was often away, directing political activities or incarcerated, while her mother was frequently bedridden with illness, and later suffered an early death from tuberculosis.[16] She had limited contact with her father, mostly through letters.[17]

Indira was taught mostly at home by tutors and attended school intermittently until matriculation in 1934. She was a student at the Modern School in Delhi, St Cecilia's and St Mary's Christian convent schools in Allahabad,[18] the International School of Geneva, the Ecole Nouvelle in Bex, and the Pupils' Own School in Poona and Bombay, which is affiliated with the University of Mumbai. [19] She and her mother Kamala moved to the Belur Math headquarters of the Ramakrishna Mission where Swami Ranganathananda was her guardian.[20] She went on to study at the Vishwa Bharati in Santiniketan, which became Visva-Bharati University in 1951.[21] It was during her interview that Rabindranath Tagore named her Priyadarshini, literally "looking at everything with kindness" in Sanskrit, and she came to be known as Indira Priyadarshini Nehru.[22] A year later, however, she had to leave university to attend to her ailing mother in Europe.[23] There it was decided that Indira would continue her education at the University of Oxford.[24][21] After her mother died, she attended the Badminton School for a brief period before enrolling at Somerville College in 1937 to study history.[25] Indira had to take the entrance examination twice, having failed at her first attempt with a poor performance in Latin.[25] At Oxford, she did well in history, political science and economics, but her grades in Latin—a compulsory subject—remained poor.[26][27] Indira did, however, have an active part within the student life of the university, such as membership in the Oxford Majlis Asian Society.[28]

During her time in Europe, Indira was plagued with ill-health and was constantly attended to by doctors. She had to make repeated trips to Switzerland to recover, disrupting her studies. She was being treated there in 1940, when Germany rapidly conquered Europe. Indira tried to return to England through Portugal but was left stranded for nearly two months. She managed to enter England in early 1941, and from there returned to India without completing her studies at Oxford. The university later awarded her an honorary degree. In 2010, Oxford honoured her further by selecting her as one of the ten Oxasians, illustrious Asian graduates from the University of Oxford.[29][1] During her stay in Great Britain, Indira frequently met her future husband Feroze Gandhi (no relation to Mahatma Gandhi), whom she knew from Allahabad, and who was studying at the London School of Economics. Their marriage took place in Allahabad according to Adi Dharm rituals, though Feroze belonged to a Zoroastrian Parsi family of Gujarat.[30] The couple had two sons, Rajiv Gandhi (born 1944) and Sanjay Gandhi (born 1946).[31][32]

In the 1950s, Indira, now Mrs. Indira Gandhi after her marriage, served her father unofficially as a personal assistant during his tenure as the first prime minister of India.[33] Towards the end of the 1950s, Gandhi served as the President of the Congress. In that capacity, she was instrumental in getting the Communist led Kerala State Government dismissed in 1959. That government had the distinction of being India's first-ever elected Communist Government.[34] After her father's death in 1964 she was appointed a member of the Rajya Sabha (upper house) and served in Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri's cabinet as Minister of Information and Broadcasting.[35] In January 1966, after Shastri's death, the Congress legislative party elected her over Morarji Desai as their leader. Congress party veteran K. Kamaraj was instrumental in Gandhi achieving victory.[36] Because she was a woman, other political leaders in India saw Gandhi as weak and hoped to use her as a puppet once elected:

Congress President Kamaraj orchestrated Mrs. Gandhi's selection as prime minister because he perceived her to be weak enough that he and the other regional party bosses could control her, and yet strong enough to beat Desai [her political opponent] in a party election because of the high regard for her father ... a woman would be an ideal tool for the Syndicate.[37]

First term as Prime Minister between 1966 and 1977

Her first eleven years serving as prime minister saw Gandhi evolve from the perception of Congress party leaders as their puppet to a strong leader with the iron resolve to split the party over her policy positions or to go to war with Pakistan to liberate Bangladesh. At the end of 1977, she was such a dominating figure in Indian politics that Congress party president D. K. Barooah had coined the phrase "India is Indira and Indira is India."[38]

First year

Gandhi formed her government with Morarji Desai as deputy prime minister and finance minister. At the beginning of her first term as prime minister, she was widely criticised by the media and the opposition as a "Goongi goodiya" (Hindi for a "dumb doll" or "puppet") of the Congress party bosses who had orchestrated her election and then tried to constrain her.[39][40]

1967–1971

The first electoral test for Gandhi was the 1967 general elections for the Lok Sabha and state assemblies. The Congress Party won a reduced majority in the Lok Sabha after these elections owing to widespread disenchantment over the rising prices of commodities, unemployment, economic stagnation and a food crisis. Gandhi was elected to the Lok Sabha from the Raebareli constituency. She had a rocky start after agreeing to devalue the rupee which created hardship for Indian businesses and consumers. The importation of wheat from the United States fell through due to political disputes.[41]

For the first time, the party also lost power or lost its majority in a number of states across the country. Following the 1967 elections, Gandhi gradually began to move towards socialist policies. In 1969, she fell out with senior Congress party leaders over several issues. Chief among them was her decision to support V. V. Giri, the independent candidate rather than the official Congress party candidate Neelam Sanjiva Reddy for the vacant position of president of India. The other was the announcement by the prime minister of Bank nationalisation without consulting the finance minister, Morarji Desai. These steps culminated in party president S. Nijalingappa expelling her from the party for indiscipline.[42][43][44] Gandhi, in turn, floated her own faction of the Congress party and managed to retain most of the Congress MPs on her side with only 65 on the side of the Congress (O) faction. The Gandhi faction, called Congress (R), lost its majority in the parliament but remained in power with the support of regional parties such as DMK.[45] The policies of the Congress under Gandhi, before the 1971 elections, also included proposals for the abolition of the Privy Purse to former rulers of the princely states and the 1969 nationalization of the fourteen largest banks in India.[46]

1971–1977

Garibi Hatao (Eradicate Poverty) was the theme for Gandhi's 1971 political bid. The slogan was developed in response to the combined opposition alliance's use of the two word manifesto—"Indira Hatao" (Remove Indira).[47][48][49] The Garibi Hatao slogan and the proposed anti-poverty programs that came with it were designed to give Gandhi independent national support, based on the rural and urban poor. This would allow her to bypass the dominant rural castes both in and of state and local governments as well as the urban commercial class. For their part, the previously voiceless poor would at last gain both political worth and political weight.[49] The programs created through Garibi Hatao, though carried out locally, were funded and developed by the Central Government in New Delhi. The program was supervised and staffed by the Indian National Congress party. "These programs also provided the central political leadership with new and vast patronage resources to be disbursed ... throughout the country."[50]

Gandhi's biggest achievement following the 1971 election came in December 1971 with India's decisive victory over Pakistan in the Indo-Pakistani War that occurred in the last two weeks of the Bangladesh Liberation War, which led to the formation of independent Bangladesh. She was said to be hailed as Goddess Durga by opposition leader Atal Bihari Vajpayee at the time.[51][52][53][54][note 1] In the elections held for State assemblies across India in March 1972, the Congress (R) swept to power in most states riding on the post-war "Indira wave".[56]

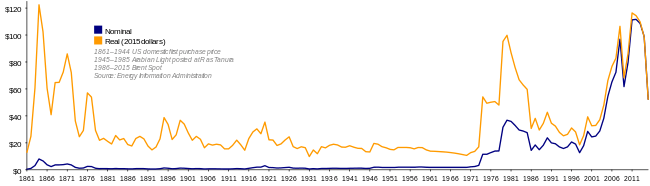

Despite the victory against Pakistan, the Congress government faced numerous problems during this term. Some of these were due to high inflation which in turn was caused by wartime expenses, drought in some parts of the country and, more importantly, the 1973 oil crisis. Opposition to her in the 1973–75 period, after the Gandhi wave had receded, was strongest in the states of Bihar and Gujarat. In Bihar, Jayaprakash Narayan, the veteran leader came out of retirement to lead the protest movement there.[56]

Verdict on electoral malpractice

On 12 June 1975, the Allahabad High Court declared Indira Gandhi's election to the Lok Sabha in 1971 void on the grounds of electoral malpractice. In an election petition filed by her 1971 opponent, Raj Narain (who later defeated her in the 1977 parliamentary election running in the Raebareli constituency), alleged several major as well as minor instances of the use of government resources for campaigning.[57][58] Gandhi had asked one of her colleagues in government, Ashoke Kumar Sen, to defend her in court. She gave evidence in her defence during the trial. After almost four years, the court found her guilty of dishonest election practices, excessive election expenditure, and of using government machinery and officials for party purposes.[57][59] The judge, however, rejected the more serious charges of bribery against her.[57]

The court ordered her stripped of her parliamentary seat and banned her from running for any office for six years. As the constitution requires that the Prime Minister must be a member of either the Lok Sabha or the Rajya Sabha, the two houses of the Parliament of India, she was effectively removed from office. However, Gandhi rejected calls to resign. She announced plans to appeal to the Supreme Court and insisted that the conviction did not undermine her position. She said: "There is a lot of talk about our government not being clean, but from our experience the situation was very much worse when [opposition] parties were forming governments."[57] And she dismissed criticism of the way her Congress Party raised election campaign money, saying all parties used the same methods. The prime minister retained the support of her party, which issued a statement backing her.

After news of the verdict spread, hundreds of supporters demonstrated outside her house, pledging their loyalty. Indian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom Braj Kumar Nehru said Gandhi's conviction would not harm her political career. "Mrs Gandhi has still today overwhelming support in the country," he said. "I believe the prime minister of India will continue in office until the electorate of India decides otherwise".[60]

State of Emergency (1975–1977)

Gandhi moved to restore order by ordering the arrest of most of the opposition participating in the unrest. Her Cabinet and government then recommended that President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed declare a state of emergency because of the disorder and lawlessness following the Allahabad High Court decision. Accordingly, Ahmed declared a State of Emergency caused by internal disorder, based on the provisions of Article 352(1) of the Constitution, on 25 June 1975.[61]

Rule by decree

Within a few months, President's rule was imposed on the two opposition party ruled states of Gujarat and Tamil Nadu thereby bringing the entire country under direct Central rule or by governments led by the ruling Congress party.[62] Police were granted powers to impose curfews and detain citizens indefinitely; all publications were subjected to substantial censorship by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. Finally, the impending legislative assembly elections were postponed indefinitely, with all opposition-controlled state governments being removed by virtue of the constitutional provision allowing for a dismissal of a state government on the recommendation of the state's governor.[63]

Indira Gandhi used the emergency provisions to change conflicting party members:

Unlike her father Jawaharlal Nehru, who preferred to deal with strong chief ministers in control of their legislative parties and state party organizations, Mrs. Gandhi set out to remove every Congress chief minister who had an independent base and to replace each of them with ministers personally loyal to her...Even so, stability could not be maintained in the states...[64]

President Ahmed issued ordinances that did not require debate in the Parliament, allowing Gandhi to rule by decree.[65]

Rise of Sanjay

The Emergency saw the entry of Gandhi's younger son, Sanjay Gandhi, into Indian politics. He wielded tremendous power during the emergency without holding any government office. According to Mark Tully, "His inexperience did not stop him from using the Draconian powers his mother, Indira Gandhi, had taken to terrorise the administration, setting up what was in effect a police state."[66]

It was said that during the Emergency he virtually ran India along with his friends, especially Bansi Lal.[67] It was also quipped that Sanjay Gandhi had total control over his mother and that the government was run by the PMH (Prime Minister House) rather than the PMO (Prime Minister Office).[68][69][70]

1977 election and opposition years

%2C_Bestanddeelnr_929-0811_(cropped).jpg)

In 1977, after extending the state of emergency twice, Gandhi called elections to give the electorate a chance to vindicate her rule. She may have grossly misjudged her popularity by reading what the heavily censored press wrote about her.[71] She was opposed by the Janata alliance of Opposition parties. The alliance was made up of Bharatiya Jana Sangh, Congress (O), The Socialist parties, and Charan Singh's Bharatiya Kranti Dal representing northern peasants and farmers. The Janata alliance, with Jai Prakash Narayan as its spiritual guide, claimed the elections were the last chance for India to choose between "democracy and dictatorship". The Congress Party split during the election campaign of 1977: veteran Gandhi supporters like Jagjivan Ram, Hemvati Nandan Bahuguna and Nandini Satpathy were compelled to part ways and form a new political entity, the CFD (Congress for Democracy), due primarily to intra-party politicking and the circumstances created by Sanjay Gandhi. The prevailing rumour was that he intended to dislodge Gandhi, and the trio stood to prevent that. Gandhi's Congress party was soundly crushed in the elections. The Janata Party's democracy or dictatorship claim seemed to resonate with the public. Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi lost their seats, and Congress was reduced to 153 seats (compared with 350 in the previous Lok Sabha), 92 of which were in the South. The Janata alliance, under the leadership of Morarji Desai, came to power after the State of Emergency was lifted. The alliance parties later merged to form the Janata Party under the guidance of Gandhian leader, Jayaprakash Narayan. The other leaders of the Janata Party were Charan Singh, Raj Narain, George Fernandes and Atal Bihari Vajpayee.[72]

In opposition and return to power

Since Gandhi had lost her seat in the election, the defeated Congress party appointed Yashwantrao Chavan as their parliamentary party leader. Soon afterwards, the Congress party split again with Gandhi floating her own Congress faction. She won a by-election in the Chikmagalur Constituency and took a seat in the Lok Sabha in November 1978 [73][74] after the Janata Party's attempts to have Kannada matinee idol Rajkumar run against her failed when he refused to contest the election saying he wanted to remain apolitical.[75] However, the Janata government's home minister, Choudhary Charan Singh, ordered her arrest along with Sanjay Gandhi on several charges, none of which would be easy to prove in an Indian court. The arrest meant that Gandhi was automatically expelled from Parliament. These allegations included that she "had planned or thought of killing all opposition leaders in jail during the Emergency".[76] In response to her arrest, Gandhi's supporters hijacked an Indian Airlines jet and demanded her immediate release.[77] However, this strategy backfired disastrously. Her arrest and long-running trial gained her sympathy from many people. The Janata coalition was only united by its hatred of Gandhi (or "that woman" as some called her). The party included right wing Hindu Nationalists, Socialists and former Congress party members. With so little in common, the Morarji Desai government was bogged down by infighting. In 1979, the government began to unravel over the issue of the dual loyalties of some members to Janata and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS)—the Hindu nationalist,[78][79] paramilitary[80] organisation. The ambitious Union finance minister, Charan Singh, who as the Union home minister during the previous year had ordered the Gandhi's' arrests, took advantage of this and started courting the Congress. After a significant exodus from the party to Singh's faction, Desai resigned in July 1979. Singh was appointed prime minister, by President Reddy, after Gandhi and Sanjay Gandhi promised Singh that Congress would support his government from outside on certain conditions.[81][82] The conditions included dropping all charges against Gandhi and Sanjay. Since Singh refused to drop them, Congress withdrew its support and President Reddy dissolved Parliament in August 1979.

Before the 1980 elections Gandhi approached the then Shahi Imam of Jama Masjid, Syed Abdullah Bukhari and entered into an agreement with him on the basis of 10-point programme to secure the support of the Muslim votes.[83] In the elections held in January, Congress returned to power with a landslide majority.[84]

1980 elections and third term

The Congress Party under Gandhi swept back into power in January 1980.[85] In this election, Gandhi was elected by the voters of the Medak constituency. Elections held soon after for legislative assemblies in States ruled by opposition parties resulted in Congress ministries in those states. Indira's son, Sanjay selected his own loyalists to head the governments in these states. On 23 June, Sanjay was killed in a plane crash while performing an aerobatic manoeuvre in New Delhi.[86] In 1980, as a tribute to her son's dream of launching an indigenously manufactured car, Gandhi nationalized Sanjay's debt ridden company, Maruti Udyog, for Rs. 43,000,000 (4.34 crore) and invited joint venture bids from automobile companies around the world. Suzuki of Japan was selected as the partner. The company launched its first Indian manufactured car in 1984.[87]

By the time of Sanjay's death, Gandhi trusted only family members, and therefore persuaded her reluctant son, Rajiv, to enter politics.[32][88]

Her PMO office staff included H.Y.Sharada Prasad as her information adviser and speechwriter.[89][90]

Operation Blue Star

Following the 1977 elections, a coalition led by the Sikh-majority Akali Dal came to power in the northern Indian state of Punjab. In an effort to split the Akali Dal and gain popular support among the Sikhs, Gandhi's Congress Party helped to bring the orthodox religious leader Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale to prominence in Punjab politics.[91][92] Later, Bhindranwale's organisation, Damdami Taksal, became embroiled in violence with another religious sect called the Sant Nirankari Mission, and he was accused of instigating the murder of Jagat Narain, the owner of the Punjab Kesari newspaper.[93] After being arrested over this matter, Bhindranwale disassociated himself from the Congress Party and joined Akali Dal.[94] In July 1982, he led the campaign for the implementation of the Anandpur Resolution, which demanded greater autonomy for the Sikh-majority state. Meanwhile, a small group of Sikhs, including some of Bhindranwale's followers, turned to militancy after being targeted by government officials and police for supporting the Anandpur Resolution.[95] In 1982, Bhindranwale and approximately 200 armed followers moved into a guest house called the Guru Nanak Niwas near the Golden Temple.[96]

By 1983, the Temple complex had become a fort for many militants.[97] The Statesman later reported that light machine guns and semi-automatic rifles were known to have been brought into the compound.[98] On 23 April 1983, the Punjab Police Deputy Inspector General A. S. Atwal was shot dead as he left the Temple compound. The following day, Harchand Singh Longowal (then president of Shiromani Akali Dal) confirmed the involvement of Bhindranwale in the murder.[99]

After several futile negotiations, in June 1984, Gandhi ordered the Indian army to enter the Golden Temple to remove Bhindranwale and his supporters from the complex. The army used heavy artillery, including tanks, in the action code-named Operation Blue Star. The operation badly damaged or destroyed parts of the Temple complex, including the Akal Takht shrine and the Sikh library. It also led to the deaths of many Sikh fighters and innocent pilgrims. The number of casualties remains disputed with estimates ranging from many hundreds to many thousands.[100]

Gandhi was accused of using the attack for political ends. Dr. Harjinder Singh Dilgeer stated that she attacked the temple complex to present herself as a great hero in order to win the general elections planned towards the end of 1984.[101] There was fierce criticism of the action by Sikhs in India and overseas.[102] There were also incidents of mutiny by Sikh soldiers in the aftermath of the attack.[100]

Assassination

The day before her death (30 October 1984), Gandhi visited Odisha where she gave her last speech at the then Parade Ground in front of the Secretariat of Odisha. In that speech, which some consider as a premonition of her imminent death, she said that she would be proud to die serving the nation: "I am alive today, I may not be there tomorrow ... I shall continue to serve until my last breath and when I die, I can say, that every drop of my blood will invigorate India and strengthen it ...[103] Even if I died in the service of the nation, I would be proud of it. Every drop of my blood ... will contribute to the growth of this nation and to make it strong and dynamic."[104]

On 31 October 1984, two of Gandhi's Sikh bodyguards, Satwant Singh and Beant Singh, shot her with their service weapons in the garden of the prime minister's residence at 1 Safdarjung Road, New Delhi, allegedly in revenge for the Operation Bluestar.[105] The shooting occurred as she was walking past a wicket gate guarded by the two men. She was to be interviewed by the British filmmaker Peter Ustinov, who was filming a documentary for Irish television.[106] Beant Singh shot her three times using his side-arm; Satwant Singh fired 30 rounds.[107] The men dropped their weapons and surrendered. Afterwards, they were taken away by other guards into a closed room where Beant Singh was shot dead. Kehar Singh was later arrested for conspiracy in the attack. Both Satwant and Kehar were sentenced to death and hanged in Delhi's Tihar Jail.[108]

Gandhi was taken to the All India Institutes of Medical Sciences at 9:30 AM where doctors operated on her. She was declared dead at 2:20 PM. The post-mortem examination was conducted by a team of doctors headed by Dr. Tirath Das Dogra. Dr. Dogra stated that Gandhi had sustained as many as 30 bullet wounds, from two sources: a Sterling submachine gun[109][110] and a pistol. The assailants had fired 31 bullets at her, of which 30 hit her; 23 had passed through her body while seven remained inside her. Dr. Dogra extracted bullets to establish the make of the weapons used and to match each weapon with the bullets recovered by ballistic examination. The bullets were matched with their respective weapons at the Central Forensic Science Laboratory (CFSL) Delhi. Subsequently, Dr. Dogra appeared in Shri Mahesh Chandra's court as an expert witness (PW-5); his testimony took several sessions. The cross examination was conducted by Shri Pran Nath Lekhi, the defence counsel.[111] Salma Sultan provided the first news of her assassination on Doordarshan's evening news on 31 October 1984, more than 10 hours after she was shot.[112][113]

Gandhi was cremated on 3 November near Raj Ghat.[114] The site where she was cremated is known today as Shakti Sthal.[115] After her death, the Parade Ground was converted to the Indira Gandhi Park which was inaugurated by her son, Rajiv Gandhi.

Her funeral was televised live on domestic and international stations, including the BBC. Attributing her assassination to Sikh bodyguards [116], Gandhi's cremation was followed by large scale anti-Sikh riots in Delhi and several other cities in which nearly three thousand people were killed.[117] On a live TV show Rajiv Gandhi said of the carnage, "When a big tree falls, the earth shakes."[118][119]

Foreign relations

Gandhi is remembered for her ability to effectively promote Indian foreign policy measures.[120]

South Asia

In early 1971, disputed elections in Pakistan led then East Pakistan to declare independence as Bangladesh. Repression and violence by the Pakistani army led to 10 million refugees crossing the border into India over the following months.[121] Finally, in December 1971, Gandhi intervened directly in the conflict to liberate Bangladesh. India emerged victorious following the war with Pakistan to become the dominant power of South Asia.[122] India had signed a treaty with the Soviet Union promising mutual assistance in the case of war,[121] while Pakistan received active support from the United States during the conflict.[123] U.S. President Richard Nixon disliked Gandhi personally, referring to her as a "witch" and a "clever fox" in his private communication with Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.[124] Nixon later wrote of the war: "[Gandhi] suckered [America]. Suckered us ... this woman suckered us."[125] Relations with the U.S. became distant as Gandhi developed closer ties with the Soviet Union after the war. The latter grew to become India's largest trading partner and its biggest arms supplier for much of Gandhi's premiership.[126] India's new hegemonic position, as articulated under the "Indira Doctrine", led to attempts to bring the Himalayan states under India's sphere of influence.[127] Nepal and Bhutan remained aligned with India, while in 1975, after years of building up support, Gandhi incorporated Sikkim into India, after a referendum in which a majority of Sikkimese voted to join India.[128][129] This was denounced as a "despicable act" by China.[130]

India maintained close ties with neighbouring Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) following the Liberation War. Prime Minister Sheikh Mujibur Rahman recognised Gandhi's contributions to the independence of Bangladesh. However, Mujibur Rahman's pro-India policies antagonised many in Bangladeshi politics and the military, which feared that Bangladesh had become a client state of India.[131][132] The Assassination of Mujibur Rahman in 1975 led to the establishment of Islamist military regimes that sought to distance the country from India.[133] Gandhi's relationship with the military regimes was strained because of her alleged support of anti-Islamist leftist guerrilla forces in Bangladesh.[133] Generally, however, there was a rapprochement between Gandhi and the Bangladeshi regimes, although issues such as border disputes and the Farakka Dam remained an irritant to bilateral ties.[134] In 2011, the Government of Bangladesh conferred its highest state award posthumously on Gandhi for her "outstanding contribution" to the country's independence.[135]

Gandhi's approach to dealing with Sri Lanka's ethnic problems was initially accommodating. She enjoyed cordial relations with Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike. In 1974, India ceded the tiny islet of Katchatheevu to Sri Lanka to save Bandaranaike's socialist government from a political disaster.[136] However, relations soured over Sri Lanka's movement away from socialism under J. R. Jayewardene, whom Gandhi despised as a "western puppet".[137] India under Gandhi was alleged to have supported the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) militants in the 1980s to put pressure on Jayewardene to abide by Indian interests.[138] Nevertheless, Gandhi rejected demands to invade Sri Lanka in the aftermath of Black July 1983, an anti-Tamil pogrom carried out by Sinhalese mobs.[139] Gandhi made a statement emphasising that she stood for the territorial integrity of Sri Lanka, although she also stated that India cannot "remain a silent spectator to any injustice done to the Tamil community."[139][140]

India's relationship with Pakistan remained strained following the Shimla Accord in 1972. Gandhi's authorisation of the detonation of a nuclear device at Pokhran in 1974 was viewed by Pakistani leader Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as an attempt to intimidate Pakistan into accepting India's hegemony in the subcontinent. However, in May 1976, Gandhi and Bhutto both agreed to reopen diplomatic establishments and normalise relations.[141] Following the rise to power of General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan in 1978, India's relations with its neighbour reached a nadir. Gandhi accused General Zia of supporting Khalistani militants in Punjab.[141] Military hostilities recommenced in 1984 following Gandhi's authorisation of Operation Meghdoot.[142] India was victorious in the resulting Siachen conflict against Pakistan.[142]

In order to keep the Soviet Union and the United States out of South Asia, Gandhi was instrumental in establishing the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 1983[143]

Middle East

Gandhi remained a staunch supporter of the Palestinians in the Arab–Israeli conflict and was critical of the Middle East diplomacy sponsored by the United States.[137] Israel was viewed as a religious state, and thus an analogue to India's archrival Pakistan. Indian diplomats hoped to win Arab support in countering Pakistan in Kashmir. Nevertheless, Gandhi authorised the development of a secret channel of contact and security assistance with Israel in the late 1960s. Her lieutenant, P. V. Narasimha Rao, later became prime minister and approved full diplomatic ties with Israel in 1992.[144]

India's pro-Arab policy had mixed success. Establishment of close ties with the socialist and secular Baathist regimes to some extent neutralised Pakistani propaganda against India.[145] However, the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 presented a dilemma for the Arab and Muslim states of the Middle East as the war was fought by two states both friendly to the Arabs.[146] The progressive Arab regimes in Egypt, Syria, and Algeria chose to remain neutral, while the conservative pro-American Arab monarchies in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and United Arab Emirates openly supported Pakistan. Egypt's stance was met with dismay by the Indians, who had come to expect close co-operation with the Baathist regimes.[145] But, the death of Nasser in 1970 and Sadat's growing friendship with Riyadh, and his mounting differences with Moscow, constrained Egypt to a policy of neutrality.[145] Gandhi's overtures to Muammar Gaddafi were rebuffed.[146] Libya agreed with the Arab monarchies in believing that Gandhi's intervention in East Pakistan was an attack against Islam.[146]

The 1971 war became a temporary stumbling block in growing Indo-Iranian ties.[145] Although Iran had earlier characterized the Indo-Pakistani war in 1965 as Indian aggression, the Shah had launched an effort at rapprochement with India in 1969 as part of his effort to secure support for a larger Iranian role in the Persian Gulf.[145] Gandhi's tilt towards Moscow and her dismemberment of Pakistan was perceived by the Shah as part of a larger anti-Iran conspiracy involving India, Iraq, and the Soviet Union.[145] Nevertheless, Iran had resisted Pakistani pressure to activate the Baghdad Pact and draw the Central Treaty Organisation (CENTO) into the conflict.[145] Gradually, Indian and Iranian disillusionment with their respective regional allies led to a renewed partnership between the nations.[147] Gandhi was unhappy with the lack of support from India's Arab allies during the war with Pakistan, while the Shah was apprehensive at the growing friendship between Pakistan and Arab states of the Persian Gulf, especially Saudi Arabia, and the growing influence of Islam in Pakistani society.[147] There was an increase in Indian economic and military co-operation with Iran during the 1970s.[147] The 1974 India-Iranian agreement led to Iran supplying nearly 75 percent of India's crude oil demands.[148] Gandhi appreciated the Shah's disregard of Pan-Islamism in diplomacy.[147]

Asia-Pacific

One of the major developments in Southeast Asia during Gandhi's premiership was the formation of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967. Relations between ASEAN and India were mutually antagonistic. India perceived ASEAN to be linked to the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) and, therefore, it was seen as a pro-American organisation. On their part, the ASEAN nations were unhappy with Gandhi's sympathy for the Viet Cong and India's strong links with the USSR. Furthermore, they were also apprehensions in the region about Gandhi's plans, particularly after India played a big role in breaking up Pakistan and facilitating the emergence of Bangladesh as a sovereign country in 1971. India's entry into the nuclear weapons club in 1974 also contributed to tensions in Southeast Asia.[149] Relations only began to improve following Gandhi's endorsement of the ZOPFAN declaration and the disintegration of the SEATO alliance in the aftermath of Pakistani and American defeats in the region. Nevertheless, Gandhi's close relations with reunified Vietnam and her decision to recognize the Vietnam-installed Government of Cambodia in 1980 meant that India and ASEAN were unable to develop a viable partnership.[149]

On 26 September 1981, Gandhi was conferred with the honorary degree of Doctor at the Laucala Graduation at the University of the South Pacific in Fiji.[150]

Africa

Although independent India was initially viewed as a champion of anti-colonialism, its cordial relationship with the Commonwealth of Nations and its liberal views of British colonial policies in East Africa had harmed its image as a staunch supporter of the anti-colonial movements.[151] Indian condemnation of militant struggles in Kenya and Algeria was in sharp contrast to China, who had supported armed struggle to win African independence.[151] After reaching a high diplomatic point in the aftermath of Nehru's role in the Suez Crisis, India's isolation from Africa was complete when only four nations—Ethiopia, Kenya, Nigeria and Libya—supported her during the Sino-Indian War in 1962.[151] After Gandhi became prime minister, diplomatic and economic relations with the states which had sided with India during the Sino-Indian War were expanded.[151] Gandhi began negotiations with the Kenyan government to establish the Africa-India Development Cooperation. The Indian government also started considering the possibility of bringing Indians settled in Africa within the framework of its policy goals to help recover its declining geo-strategic influence. Gandhi declared the people of Indian origin settled in Africa as "Ambassadors of India".[151] Efforts to rope in the Asian community to join Indian diplomacy, however, came to naught, in part because of the unwillingness of Indians to remain in politically insecure surroundings, and because of the exodus of African Indians to Britain with the passing of the Commonwealth Immigrants Act in 1968.[151] In Uganda, the African Indian community suffered persecution and eventually expulsion under the government of Idi Amin.[152]

Foreign and domestic policy successes in the 1970s enabled Gandhi to rebuild India's image in the eyes of African states.[151] Victory over Pakistan and India's possession of nuclear weapons showed the degree of India's progress.[151] Furthermore, the conclusion of the Indo-Soviet treaty in 1971, and threatening gestures by the United States, to send its nuclear armed Task Force 74 into the Bay of Bengal at the height of the East Pakistan crisis had enabled India to regain its anti-imperialist image.[151] Gandhi firmly tied Indian anti-imperialist interests in Africa to those of the Soviet Union.[153] Unlike Nehru, she openly and enthusiastically supported liberation struggles in Africa.[153] At the same time, Chinese influence in Africa had declined owing to its incessant quarrels with the Soviet Union.[151] These developments permanently halted India's decline in Africa and helped to reestablish its geo-strategic presence.[151]

The Commonwealth

The Commonwealth is a voluntary association of mainly former British colonies. India maintained cordial relations with most of the members during Gandhi's time in power. In the 1980s, she, along with Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau, Zambia's president Kenneth Kaunda, Australian prime minister Malcolm Fraser and Singapore prime minister Lee Kuan Yew was regarded as one of the pillars[154] India under Gandhi also hosted the 1983 Commonwealth Heads of Government summit in New Delhi. Gandhi used these meetings as a forum to put pressure on member countries to cut economic, sports, and cultural ties with Apartheid South Africa.[155]

The Non-aligned Movement

In the early 1980s under Gandhi, India attempted to reassert its prominent role in the Non-Aligned Movement by focusing on the relationship between disarmament and economic development. By appealing to the economic grievances of developing countries, Gandhi and her successors exercised a moderating influence on the Non-aligned movement, diverting it from some of the Cold War issues that marred the controversial 1979 Havana meeting where Cuban leader Fidel Castro attempted to steer the movement towards the Soviet Union.[156] Although hosting the 1983 summit at Delhi boosted Indian prestige within the movement, its close relations with the Soviet Union and its pro-Soviet positions on Afghanistan and Cambodia limited its influence.

Western Europe

Gandhi spent a number of years in Europe during her youth and had formed many friendships there. During her premiership she formed friendships with many leaders such as West German chancellor, Willy Brandt[157] and Austrian chancellor Bruno Kreisky.[158] She also enjoyed a close working relationship with many British leaders including conservative premiers, Edward Heath and Margaret Thatcher.[159]

Soviet Union and Eastern block countries

The relationship between India and the Soviet Union deepened during Gandhi's rule. The main reason was the perceived bias of the United States and China, rivals of the USSR, towards Pakistan. The support of the Soviets with arms supplies and the casting of a veto at the United Nations helped in winning and consolidating the victory over Pakistan in the 1971 Bangladesh liberation war. Before the war, Gandhi signed a treaty of friendship with the Soviets. They were unhappy with the 1974 nuclear test conducted by India but did not support further action because of the ensuing Cold War with the United States. Gandhi was unhappy with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, but once again calculations involving relations with Pakistan and China kept her from criticising the Soviet Union harshly. The Soviets became the main arms supplier during the Gandhi years by offering cheap credit and transactions in rupees rather than in dollars. The easy trade deals also applied to non-military goods. Under Gandhi, by the early 1980s, the Soviets had become India's largest trading partner.[160]

United States

.tif.jpg)

When Gandhi came to power in 1966, Lyndon Johnson was the US president. At the time, India was reliant on the US for food aid. Gandhi resented the US policy of food aid being used as a tool to force India to adopt policies favoured by the US. She also resolutely refused to sign the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). Relations with the US were strained badly under President Richard Nixon and his favouring of Pakistan during the Bangladesh liberation war. Nixon despised Gandhi politically and personally.[161] In 1981, Gandhi met President Ronald Reagan for the first time at the North–South Summit held to discuss global poverty. She had been described to him as an 'Ogre', but he found her charming and easy to work with and they formed a close working relationship during her premiership in the 1980s.[162]

Economic policy

Gandhi presided over three Five-Year Plans as prime minister, two of which succeeded in meeting their targeted growth.[163]

There is considerable debate whether Gandhi was a socialist on principle or out of political expediency.[45] Sunanda K. Datta-Ray described her as "a master of rhetoric ... often more posture than policy", while The Times journalist, Peter Hazelhurst, famously quipped that Gandhi's socialism was "slightly left of self-interest."[164] Critics have focused on the contradictions in the evolution of her stance towards communism. Gandhi was known for her anti-communist stance in the 1950s, with Meghnad Desai even describing her as "the scourge of [India's] Communist Party."[165] Yet, she later forged close relations with Indian communists even while using the army to break the Naxalites. In this context, Gandhi was accused of formulating populist policies to suit her political needs. She was seemingly against the rich and big business while preserving the status quo to manipulate the support of the left in times of political insecurity, such as the late 1960s.[166][167] Although in time Gandhi came to be viewed as the scourge of the right-wing and reactionary political elements of India, leftist opposition to her policies emerged. As early as 1969, critics had begun accusing her of insincerity and machiavellianism. The Indian Libertarian wrote that: "it would be difficult to find a more machiavellian leftist than Mrs Indira Gandhi ... for here is Machiavelli at its best in the person of a suave, charming and astute politician."[168] J. Barkley Rosser Jr. wrote that "some have even seen the declaration of emergency rule in 1975 as a move to suppress [leftist] dissent against Gandhi's policy shift to the right."[45] In the 1980s, Gandhi was accused of "betraying socialism" after the beginning of Operation Forward, an attempt at economic reform.[169] Nevertheless, others were more convinced of Gandhi's sincerity and devotion to socialism. Pankaj Vohra noted that "even the late prime minister's critics would concede that the maximum number of legislations of social significance was brought about during her tenure ... [and that] she lives in the hearts of millions of Indians who shared her concern for the poor and weaker sections and who supported her politics."[170]

In summarising the biographical works on Gandhi, Blema S. Steinberg concludes she was decidedly non-ideological.[171] Only 7.4% (24) of the total 330 biographical extractions posit ideology as a reason for her policy choices.[171] Steinberg notes Gandhi's association with socialism was superficial. She had only a general and traditional commitment to the ideology by way of her political and family ties.[171] Gandhi personally had a fuzzy concept of socialism. In one of the early interviews she gave as prime minister, Gandhi had ruminated: "I suppose you could call me a socialist, but you have understand what we mean by that term ... we used the word [socialism] because it came closest to what we wanted to do here – which is to eradicate poverty. You can call it socialism; but if by using that word we arouse controversy, I don't see why we should use it. I don't believe in words at all."[171] Regardless of the debate over her ideology or lack thereof, Gandhi remains a left-wing icon. She has been described by Hindustan Times columnist, Pankaj Vohra, as "arguably the greatest mass leader of the last century."[170] Her campaign slogan, Garibi Hatao ('Remove Poverty'), has become an often used motto of the Indian National Congress Party.[172] To the rural and urban poor, untouchables, minorities and women in India, Gandhi was "Indira Amma or Mother Indira."[173]

Green Revolution and the Fourth Five-Year Plan

Gandhi inherited a weak and troubled economy. Fiscal problems associated with the war with Pakistan in 1965, along with a drought-induced food crisis that spawned famines, had plunged India into the sharpest recession since independence.[41][45] The government responded by taking steps to liberalise the economy and agreeing to the devaluation of the currency in return for the restoration of foreign aid.[41] The economy managed to recover in 1966 and ended up growing at 4.1% over 1966–1969.[166][174] Much of that growth, however, was offset by the fact that the external aid promised by the United States government and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), meant to ease the short-run costs of adjustment to a liberalised economy, never materialised.[41] American policy makers had complained of continued restrictions imposed on the economy. At the same time, Indo-US relations were strained because of Gandhi's criticism of the American bombing campaign in Vietnam. While it was thought at the time, and for decades after, that President Johnson's policy of withholding food grain shipments was to coerce Indian support for the war, in fact, it was to offer India rainmaking technology that he wanted to use as a counterweight to China's possession of the atomic bomb.[175][176] In light of the circumstances, liberalisation became politically suspect and was soon abandoned.[41] Grain diplomacy and currency devaluation became matters of intense national pride in India. After the bitter experience with Johnson, Gandhi decided not to request food aid in the future. Moreover, her government resolved never again to become "so vulnerably dependent" on aid, and painstakingly began building up substantial foreign exchange reserves.[177] When food stocks slumped after poor harvests in 1972, the government made it a point to use foreign exchange to buy US wheat commercially rather than seek resumption of food aid.[178]

The period of 1967–75 was characterised by socialist ascendency in India, which culminated in 1976 with the official declaration of state socialism. Gandhi not only abandoned the short-lived liberalisation programme but also aggressively expanded the public sector with new licensing requirements and other restrictions for industry. She began a new course by launching the Fourth Five-Year Plan in 1969. The government targeted growth at 5.7% while stating as its goals, "growth with stability and progressive achievement of self-reliance."[166][179] The rationale behind the overall plan was Gandhi's Ten-Point Programme of 1967. This had been her first economic policy formulation, six months after coming to office. The programme emphasised greater state control of the economy with the understanding that government control assured greater welfare than private control.[166] Related to this point were a set of policies which were meant to regulate the private sector.[166] By the end of the 1960s, the reversal of the liberalisation process was complete, and India's policies were characterised as "protectionist as ever."[177]

To deal with India's food problems, Gandhi expanded the emphasis on production of inputs to agriculture that had already been initiated by her father, Jawaharlal Nehru.[45] The Green Revolution in India subsequently culminated under her government in the 1970s. It transformed the country from a nation heavily reliant on imported grains, and prone to famine, to one largely able to feed itself, and becoming successful in achieving its goal of food security. Gandhi had a personal motive in pursuing agricultural self-sufficiency, having found India's dependency on the U.S. for shipments of grains humiliating.[180]

The economic period of 1967–75 became significant for its major wave of nationalisation amidst increased regulation of the private sector.[45]

Some other objectives of the economic plan for the period were to provide for the minimum needs of the community through a rural works program and the removal of the privy purses of the nobility.[166] Both these, and many other goals of the 1967 programme, were accomplished by 1974–75. Nevertheless, the success of the overall economic plan was tempered by the fact that annual growth at 3.3–3.4% over 1969–74 fell short of the targeted figure.[166]

State of Emergency and the Fifth Five-Year Plan

The Fifth Five-Year Plan (1974–79) was enacted against the backdrop of the state of emergency and the Twenty Point Program of 1975.[166] It was the economic rationale of the emergency, a political act which has often been justified on economic grounds.[166] In contrast to the reception of Gandhi's earlier economic plan, this one was criticised for being a "hastily thrown together wish list."[166] Gandhi promised to reduce poverty by targeting the consumption levels of the poor and enact wide-ranging social and economic reforms. In addition, the government targeted an annual growth rate of 4.4% over the period of the plan.[163]

The measures of the emergency regime was able to halt the economic trouble of the early to mid-1970s, which had been marred by harvest failures, fiscal contraction, and the breakdown of the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchanged rates. The resulting turbulence in the foreign exchange markets was accentuated further by the oil shock of 1973.[174] The government was able to exceed the targeted growth figure with an annual growth rate of 5.0–5.2% over the five-year period of the plan (1974–79).[163][166] The economy grew at the rate of 9% in 1975–76 alone, and the Fifth Plan, became the first plan during which the per capita income of the economy grew by over 5%.[181]

Operation Forward and the Sixth Five-Year Plan

Gandhi inherited a weak economy when she became prime minister again in 1980.[182] The preceding year—1979–80—under the Janata Party government saw the strongest recession (−5.2%) in the history of modern India with inflation rampant at 18.2%.[45][181][183] Gandhi proceeded to abrogate the Janata Party government's Five-Year Plan in 1980 and launched the Sixth Five-Year Plan (1980–85). Her government targeted an average growth rate of 5.2% over the period of the plan.[163] Measures to check inflation were also taken; by the early 1980s it was under control at an annual rate of about 5%.[183]

Although Gandhi continued professing socialist beliefs, the Sixth Five-Year Plan was markedly different from the years of Garibi Hatao. Populist programmes and policies were replaced by pragmatism.[166] There was an emphasis on tightening public expenditures, greater efficiency of the state-owned enterprises (SOE), which Gandhi qualified as a "sad thing", and on stimulating the private sector through deregulation and liberation of the capital market.[184] The government subsequently launched Operation Forward in 1982, the first cautious attempt at reform.[185] The Sixth Plan went on to become the most successful of the Five-Year Plans yet; showing an average growth rate of 5.7% over 1980–85.[163]

Inflation and unemployment

During Lal Bahadur Shastri's last full year in office (1965), inflation averaged 7.7%, compared to 5.2% at the end of Gandhi's first term in office (1977).[186] On average, inflation in India had remained below 7% through the 1950s and 1960s.[187] It then accelerated sharply in the 1970s, from 5.5% in 1970–71 to over 20% by 1973–74, due to the international oil crisis.[186] Gandhi declared inflation the gravest of problems in 1974 (at 25.2%) and devised a severe anti-inflation program. The government was successful in bringing down inflation during the emergency; achieving negative figures of −1.1% by the end of 1975–76.[182][186]

Gandhi inherited a tattered economy in her second term; harvest failures and a second oil shock in the late 1970s had caused inflation to rise again.[182] During Charan Singh's short time in office in the second half of 1979, inflation averaged 18.2%, compared to 6.5% during Gandhi's last year in office (1984).[183][186] General economic recovery under Gandhi led to an average inflation rate of 6.5% from 1981–82 to 1985–86—the lowest since the beginning of India's inflation problems in the 1960s.[187]

The unemployment rate remained constant at 9% over a nine-year period (1971–80) before declining to 8.3% in 1983.[166][188]

Domestic policy

Nationalisation

Despite the provisions, control and regulations of the Reserve Bank of India, most banks in India had continued to be owned and operated by private persons.[189] Businessmen who owned the banks were often accused of channeling the deposits into their own companies and ignoring priority sector lending. Furthermore, there was a great resentment against class banking in India, which had left the poor (the majority of the population) unbanked.[190] After becoming prime minister, Gandhi expressed her intention of nationalising the banks to alleviate poverty in a paper titled, "Stray thoughts on Bank Nationalisation".[191] The paper received overwhelming public support.[191] In 1969, Gandhi moved to nationalise fourteen major commercial banks. After this, public sector bank branch deposits increased by approximately 800 percent; advances took a huge jump by 11,000 percent.[192] Nationalisation also resulted in significant growth in the geographic coverage of banks; the number of bank branches rose from 8,200 to over 62,000, most of which were opened in unbanked, rural areas. The nationalisation drive not only helped to increase household savings, but it also provided considerable investments in the informal sector, in small- and medium-sized enterprises, and in agriculture, and contributed significantly to regional development and to the expansion of India's industrial and agricultural base.[193] Jayaprakash Narayan, who became famous for leading the opposition to Gandhi in the 1970s, solidly praised her nationalisation of banks.[190]

Having been re-elected in 1971 on a nationalisation platform, Gandhi proceeded to nationalise the coal, steel, copper, refining, cotton textiles, and insurance industries.[45] Most of this was done to protect employment and the interests of organised labour.[45] The remaining private sector industries were placed under strict regulatory control.[45]

During the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, foreign-owned private oil companies had refused to supply fuel to the Indian Navy and the Indian Air Force. In response, Gandhi nationalised oil companies in 1973.[194] After nationalisation, the oil majors such as the Indian Oil Corporation (IOC), the Hindustan Petroleum Corporation (HPCL) and the Bharat Petroleum Corporation (BPCL) had to keep a minimum stock level of oil, to be supplied to the military when needed.[195]

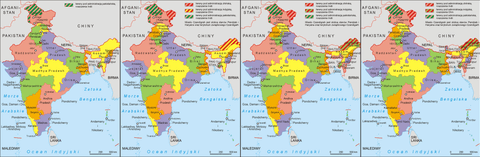

Administration

In 1966, Gandhi accepted the demands of the Akalis to reorganise Punjab on linguistic lines. The Hindi-speaking southern half of Punjab became a separate state, Haryana, while the Pahari speaking hilly areas in the northeast were joined to Himachal Pradesh.[196] By doing this she had hoped to ward off the growing political conflict between Hindu and Sikh groups in the region.[196] However, a contentious issue that was considered unresolved by the Akalis was the status of Chandigarh, a prosperous city on the Punjab-Haryana border, which Gandhi declared a union territory to be shared as a capital by both the states.[197]

Victory over Pakistan in 1971 consolidated Indian power in Kashmir. Gandhi indicated that she would make no major concessions on Kashmir. The most prominent of the Kashmiri separatists, Sheikh Abdullah, had to recognise India's control over Kashmir in light of the new order in South Asia. The situation was normalised in the years following the war after Abdullah agreed to an accord with Gandhi, by giving up the demand for a plebiscite in return for a special autonomous status for Kashmir. In 1975, Gandhi declared the state of Jammu and Kashmir as a constituent unit of India. The Kashmir conflict remained largely peaceful if frozen under Gandhi's premiership.[198]

In 1972, Gandhi granted statehood to Meghalaya, Manipur and Tripura, while the North-East Frontier Agency was declared a union territory and renamed Arunachal Pradesh. The transition to statehood for these territories was successfully overseen by her administration.[199] This was followed by the annexation of Sikkim in 1975.[129]

Social reform

The principle of equal pay for equal work for both men and women was enshrined in the Indian Constitution under the Gandhi administration.[200]

Gandhi questioned the continued existence of a privy purse for former rulers of princely states. She argued the case for abolition based on equal rights for all citizens and the need to reduce the government's revenue deficit. The nobility responded by rallying around the Jana Sangh and other right-wing parties that stood in opposition to Gandhi's attempts to abolish royal privileges.[167] The motion to abolish privy purses, and the official recognition of the titles, was originally brought before the Parliament in 1970. It was passed in the Lok Sabha but fell short of the two-thirds majority in the Rajya Sabha by a single vote.[201] Gandhi responded by having a Presidential proclamation issued; de-recognising the princes; with this withdrawal of recognition, their claims to privy purses were also legally lost.[201] However, the proclamation was struck down by the Supreme Court of India.[201] In 1971, Gandhi again motioned to abolish the privy purse. This time, it was passed successfully as the 26th Amendment to the Constitution of India.[167] Many royals tried to protest the abolition of the privy purse, primarily through campaigns to contest seats in elections. However, they received a final setback when many of them were defeated by huge margins.

Gandhi claimed that only "clear vision, iron will and the strictest discipline" can remove poverty.[167] She justified the imposition of the state of emergency in 1975 in the name of the socialist mission of the Congress.[167] Armed with the power to rule by decree and without constitutional constraints, Gandhi embarked on a massive redistribution program.[167] The provisions included rapid enforcement of land ceilings, housing for landless labourers, the abolition of bonded labour and a moratorium on the debts of the poor.[167] North India was at the centre of the reforms. millions of acres of land were acquired and redistributed.[167] The government was also successful in procuring houses for landless labourers; According to Francine Frankel, three-fourths of the targeted four million houses was achieved in 1975 alone.[167] Nevertheless, others have disputed the success of the program and criticised Gandhi for not doing enough to reform land ownership. The political economist, Jyotindra Das Gupta, cryptically questioned "...whether or not the real supporters of land-holders were in jail or in power?"[167] Critics also accused Gandhi of choosing to "talk left and act right", referring to her concurrent pro-business decisions and endeavours.[167] J. Barkley Rosser Jr. wrote that "some have even seen the declaration of emergency rule in 1975 as a move to suppress dissent against Gandhi's policy shift to the right."[45] Regardless of the controversy over the nature of the reforms, the long-term effects of the social changes gave rise to the prominence of middle-ranking farmers from intermediate and lower castes in North India.[167] The rise of these newly empowered social classes challenged the political establishment of the Hindi Belt in the years to come.[167]

Language policy

Under the 1950 Constitution of India, Hindi was to have become the official national language by 1965. This was unacceptable to many non-Hindi speaking states, which wanted the continued use of English in government. In 1967, Gandhi introduced a constitutional amendment that guaranteed the de facto use of both Hindi and English as official languages. This established the official government policy of bilingualism in India and satisfied the non-Hindi speaking Indian states.[171] Gandhi thus put herself forward as a leader with a pan-Indian vision.[202] Nevertheless, critics alleged that her stance was actually meant to weaken the position of rival Congress leaders from the northern states such as Uttar Pradesh, where there had been strong, sometimes violent, pro-Hindi agitations.[171] Gandhi came out of the language conflicts with the strong support of the south Indian populace.[202]

National security

In the late 1960s and 1970s, Gandhi had the Indian army crush militant Communist uprisings in the Indian state of West Bengal.[203] The communist insurgency in India was completely suppressed during the state of emergency.[204][205][206]

Gandhi considered the north-eastern region important, because of its strategic situation.[207] In 1966, the Mizo uprising took place against the government of India and overran almost the whole of the Mizoram region. Gandhi ordered the Indian Army to launch massive retaliatory strikes in response. The rebellion was suppressed with the Indian Air Force carrying out airstrikes in Aizawl; this remains the only instance of India carrying out an airstrike in its own territory.[199][208] The defeat of Pakistan in 1971 and the secession of East Pakistan as pro-India Bangladesh led to the collapse of the Mizo separatist movement. In 1972, after the less extremist Mizo leaders came to the negotiating table, Gandhi upgraded Mizoram to the status of a union territory. A small-scale insurgency by some militants continued into the late 1970s, but it was successfully dealt with by the government.[199] The Mizo conflict was resolved definitively during the administration of Gandhi's son Rajiv. Today, Mizoram is considered one of the most peaceful states in the north-east.[209]

Responding to the insurgency in Nagaland, Gandhi "unleashed a powerful military offensive" in the 1970s.[210] Finally, a massive crackdown on the insurgents took place during the state of emergency ordered by Gandhi. The insurgents soon agreed to surrender and signed the Shillong Accord in 1975.[211] While the agreement was considered a victory for the Indian government and ended large-scale conflicts,[212] there have since been spurts of violence by rebel holdouts and ethnic conflict amongst the tribes.[212]

India's nuclear programme

Gandhi contributed to, and carried out further, the vision of Jawaharlal Nehru, former premier of India, to develop its nuclear program.[213][214] Gandhi authorised the development of nuclear weapons in 1967, in response to Test No. 6 by the People's Republic of China. Gandhi saw this test as Chinese nuclear intimidation and promoted Nehru's views to establish India's stability and security interests independent from those of the nuclear superpowers.[215]

The programme became fully mature in 1974, when Dr. Raja Ramanna reported to Gandhi that India had the ability to test its first nuclear weapon. Gandhi gave verbal authorisation for this test, and preparations were made in the Indian Army's Pokhran Test Range.[213] In 1974, India successfully conducted an underground nuclear test, unofficially code named "Smiling Buddha", near the desert village of Pokhran in Rajasthan.[216] As the world was quiet about this test, a vehement protest came from Pakistan as its prime minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, described the test as "Indian hegemony" to intimidate Pakistan.[217] In response to this, Bhutto launched a massive campaign to make Pakistan a nuclear power. Bhutto asked the nation to unite and slogans such as "hum ghaas aur pattay kha lay gay magar nuclear power ban k rhe gay" ("We will eat grass or leaves or even go hungry, but we will get nuclear power") were employed. Gandhi directed a letter to Bhutto, and later to the world, claiming the test was for peaceful purposes and part of India's commitment to develop its programme for industrial and scientific use.[218]

Family, personal life and outlook

She married Feroze Gandhi at the age of 25, in 1942. Their marriage lasted 18 years until he died of a heart attack in 1960.[219] They had two sons—Rajiv (b. 1944) and Sanjay (b. 1946). Initially, her younger son Sanjay had been her chosen heir, but after his death in a flying accident in June 1980, Gandhi persuaded her reluctant elder son Rajiv to quit his job as a pilot and enter politics in February 1981. Rajiv took office as prime minister following his mother's assassination in 1984; he served until December 1989. Rajiv Gandhi himself was assassinated by a suicide bomber working on behalf of LTTE on 21 May 1991.[220]

Gandhi's yoga guru, Dhirendra Brahmachari, helped her in making certain decisions and also executed certain top level political tasks on her behalf, especially from 1975 to 1977 when Gandhi "declared a state of emergency and suspended civil liberties."[221][222]

Views on women

In 1952 in a letter to her American friend Dorothy Norman, Gandhi wrote: "I am in no sense a feminist, but I believe in women being able to do everything ... Given the opportunity to develop, capable Indian women have come to the top at once." While this statement appears paradoxical, it reflects Gandhi's complex feelings toward her gender and feminism.[223] Her egalitarian upbringing with her cousins helped contribute to her sense of natural equality. "Flying kites, climbing trees, playing marbles with her boy cousins, Indira said she hardly knew the difference between a boy and a girl until the age of twelve."[224][225]

Gandhi did not often discuss her gender, but she did involve herself in women's issues before becoming the prime minister. Before her election as prime minister, she became active in the organisational wing of the Congress party, working in part in the Women's Department.[226] In 1956, Gandhi had an active role in setting up the Congress Party's Women's Section.[227] Unsurprisingly, a lot of her involvement stemmed from her father. As an only child, Gandhi naturally stepped into the political light. And, as a woman, she naturally helped head the Women's section of the Congress Party. She often tried to organise women to involve themselves in politics.[228] Although rhetorically Gandhi may have attempted to separate her political success from her gender, Gandhi did involve herself in women's organizations. The political parties in India paid substantial attention to Gandhi's gender before she became prime minister, hoping to use her for political gain.[229][230] Even though men surrounded Gandhi during her upbringing, she still had a female role model as a child. Several books on Gandhi mention her interest in Joan of Arc. In her own accounts through her letters, she wrote to her friend Dorothy Norman, in 1952 she wrote: "At about eight or nine I was taken to France; Jeanne d'Arc became a great heroine of mine. She was one of the first people I read about with enthusiasm."[231] Another historian recounts Indira's comparison of herself to Joan of Arc: "Indira developed a fascination for Joan of Arc, telling her aunt, 'Someday I am going to lead my people to freedom just as Joan of Arc did'!"[232] Gandhi's linking of herself to Joan of Arc presents a model for historians to assess Gandhi. As one writer said: "The Indian people were her children; members of her family were the only people capable of leading them."[233]

Gandhi had been swept up in the call for Indian independence since she was born in 1917.[234] Thus by 1947, she was already well immersed in politics, and by 1966, when she first assumed the position of prime minister, she had held several cabinet positions in her father's office.[235]

Gandhi's advocacy for women's rights began with her help in establishing the Congress Party's Women's Section.[226] In 1956, she wrote in a letter: "It is because of this that I am taking a much more active part in politics. I have to do a great deal of touring in order to set up the Congress Party Women's Section, and am on numerous important committees."[227] Gandhi spent a great deal of time throughout the 1950s helping to organise women. She wrote to Norman in 1959, irritable that women had organised around the communist cause but had not mobilised for the Indian cause: "The women, whom I have been trying to organize for years, had always refused to come into politics. Now they are out in the field."[236] Once appointed president in 1959, she "travelled relentlessly, visiting remote parts of the country that had never before received a VIP ... she talked to women, asked about child health and welfare, inquired after the crafts of the region"[237] Gandhi's actions throughout her ascent to power clearly reflect a desire to mobilise women. Gandhi did not see the purpose of feminism. She saw her own success as a woman, and also noted that: "Given the opportunity to develop, capable Indian women have come to the top at once."[223]

Gandhi felt guilty about her inability to fully devote her time to her children. She noted that her main problem in office was how to balance her political duties with tending to her children, and "stressed that motherhood was the most important part of her life."[238] At another point, she went into more detail: "To a woman, motherhood is the highest fulfilment ... To bring a new being into this world, to see its perfection and to dream of its future greatness is the most moving of all experiences and fills one with wonder and exaltation."[239]

Her domestic initiatives did not necessarily reflect favourably on Indian women. Gandhi did not make a special effort to appoint women to cabinet positions. She did not appoint any women to full cabinet rank during her terms in office.[120] Yet despite this, many women saw Gandhi as a symbol for feminism and an image of women's power.[120]

Legacy

After leading India to victory against Pakistan in the Bangladesh liberation war in 1971, President V. V. Giri awarded Gandhi with India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna.[240][241][242]

In 2011, the Bangladesh Freedom Honour (Bangladesh Swadhinata Sammanona), Bangladesh's highest civilian award, was posthumously conferred on Gandhi for her "outstanding contributions" to Bangladesh's Liberation War.[243]

Gandhi's main legacy was standing firm in the face of American pressure to defeat Pakistan and turn East Pakistan into independent Bangladesh.[121] She was also responsible for India joining the group of countries with nuclear weapons.[216] Despite India being officially part of the Non-Aligned Movement, she gave Indian foreign policy a tilt towards the Soviet bloc.[160] In 1999, Gandhi was named "Woman of the Millennium" in an online poll organised by the BBC.[244] In 2012, she was ranked number seven on Outlook India's poll of the Greatest Indian.[245]

Being at the forefront of Indian politics for decades, Gandhi left a powerful but controversial legacy on Indian politics. The main legacy of her rule was destroying internal party democracy in the Congress party. Her detractors accuse her of weakening State chief ministers and thereby weakening the federal structure, weakening the independence of the judiciary, and weakening her cabinet by vesting power in her secretariat and her sons.[246] Gandhi is also associated with fostering a culture of nepotism in Indian politics and in India's institutions.[247] She is also almost singularly associated with the period of Emergency rule and the dark period in Indian Democracy that it entailed.[248]

The Congress party was a "broad church" during the independence movement; however, it started turning into a family firm controlled by Indira Gandhi's family during the emergency. This was characterised by servility and sycophancy towards the family which later turned into a hereditary succession of Gandhi family members to power.[249]

Her actions in storming the Golden Temple alienated Sikhs for a very long time.[250]

One of her legacies is supposed to be the systematic corruption of all parts of India's government from the executive to the judiciary due to her sense of insecurity.[251] The Forty-second Amendment of the Constitution of India which was adopted during the emergency can also be regarded as part of her legacy. Although judicial challenges and non-Congress governments tried to water down the amendment, the amendment still stands.[252]

Although the Maruti Udyog company was first established by Gandhi's son, Sanjay, it was under Indira that the then nationalized company came to prominence.[87]

She remains the only woman to occupy the Office of the Prime Minister of India.[253] In 2020 Gandhi was named by the Time magazine among world's 100 powerful women who defined the last century[8][9]

Posthumous honours

- The southernmost Indira Point (6.74678°N 93.84260°E) is named after Gandhi.

- The Indira Awaas Yojana, a central government low-cost housing programme for the rural poor, was named after her.

- The international airport at New Delhi is named Indira Gandhi International Airport in her honour.

- The Indira Gandhi National Open University, the largest university in the world, is also named after her.

- Indian National Congress established the annual Indira Gandhi Award for National Integration in 1985, given in her memory on her death anniversary.