North–South divide

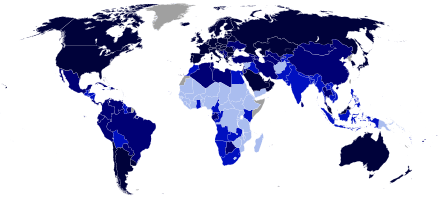

The North–South divide is a socio-economic and political division of Earth popularized in the late 20th century and early 21st century. Generally, definitions of the Global North include the United States, Canada, almost all the European countries, Israel, Cyprus, Japan, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, and New Zealand. The Global South is made up of Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Pacific Islands, and the developing countries in Asia, including the Middle East. It is home to the BRIC countries (excluding Russia): Brazil, India and China, which, along with Indonesia and Mexico, are the largest Southern states in terms of land area and population.

Blue above world GDP (PPP) per capita

Orange below world GDP (PPP) per capita

The North is mostly correlated with the Western world and the First World, plus much of the Second World, while the South largely corresponds with the Third World and Eastern world. The two groups are often defined in terms of their differing levels of wealth, economic development, income inequality, democracy, and political and economic freedom, as defined by freedom indices. Nations in the North tend to be wealthier, less unequal and considered more democratic and to be developed countries who export technologically advanced manufactured products; Southern states are generally poorer developing countries with younger, more fragile democracies heavily dependent on primary sector exports and frequently share a history of past colonialism by Northern states.[1][1] Nevertheless, the divide between the North and the South is often challenged and said to be increasingly incompatible with reality.[2]

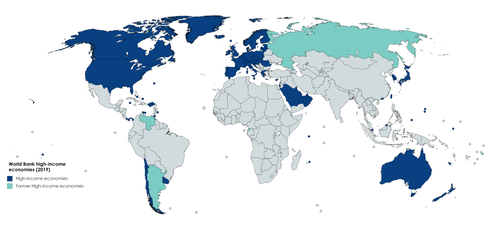

In economic terms, as of the early 21st century, the North—with one quarter of the world population—controls four-fifths of the income earned anywhere in the world. 90% of the manufacturing industries are owned by and located in the North.[1] Inversely, the South—with three quarters of the world population—has access to one-fifth of the world income. As nations become economically developed, they may become part of definitions the "North", regardless of geographical location; similarly, any nations that do not qualify for "developed" status are in effect deemed to be part of the "South".[3]

History

The idea of categorizing countries by their economic and developmental status began during the Cold War with the classifications of East and West. The Soviet Union and China represented the East, and the United States and their allies represented the West. The term 'Third World' came into parlance in the second half of the twentieth century. It originated in a 1952 article by Alfred Sauvy entitled "Trois Mondes, Une Planète."[4] Early definitions of the Third World emphasized its exclusion from the East-West conflict of the Cold War as well as the ex-colonial status and poverty of the nations it comprised.[4] Efforts to mobilize the Third World as an autonomous political entity were undertaken. The 1955 Bandung Conference was an early meeting of Third World states in which an alternative to alignment with either the Eastern or Western Blocs was promoted.[4] Following this, the first Non-Aligned Summit was organized in 1961. Contemporaneously, a mode of economic criticism which separated the world economy into "core" and "periphery" was developed and given expression in a project for political reform which "moved the terms 'North' and 'South' into the international political lexicon."[5] In 1973, the pursuit of a New International Economic Order which was to be negotiated between the North and South was initiated at the Non-Aligned Summit held in Algiers.[6] Also in 1973, the oil embargo initiated by Arab OPEC countries as a result of the Yom Kippur War caused an increase in world oil prices, with prices continuing to rise throughout the decade.[7] This contributed to a worldwide recession which resulted in industrialized nations increasing economically protectionist policies and contributing less aid to the less developed countries of the South.[7] The slack was taken up by Western banks, which provided substantial loans to Third World countries.[8] However, many of these countries were not able to pay back their debt, which led the IMF to EXtended further loans to them on the condition that they undertake certain liberalizing reforms.[8] This policy, which came to be known as structural adjustment, and was institutionalized by International Financial Institutions (IFIs) and Western governments, represented a break from the Keynesian approach to foreign aid which had been the norm from the end of the Second World War.[8] After 1987, reports on the negative social impacts that structural adjustment policies had had on affected developing nations led IFIs to supplement structural adjustment policies with targeted anti-poverty projects.[9] Following the end of the Cold War and the break-up of the Soviet Union, some Second World countries joined the First World, and others joined the Third World. A new and simpler classification was needed. Use of the terms "North" and "South" became more widespread.

Defining development

Being categorized as part of the "North" implies development as opposed to belonging to the "South", which implies a lack thereof. According to N. Oluwafemi Mimiko, the South lacks the right technology, it is politically unstable, its economies are divided, and its foreign exchange earnings depend on primary product exports to the North, along with the fluctuation of prices. The low level of control it exercises over imports and exports condemns the South to conform to the 'imperialist' system. The South's lack of development and the high level of development of the North deepen the inequality between them and leave the South a source of raw material for the developed countries.[10] The north becomes synonymous with economic development and industrialization while the South represents the previously colonized countries which are in need of help in the form of international aid agendas.[11] In order to understand how this divide occurs, a definition of "development" itself is needed. Northern countries are using most of the earth resources and most of them are high entropic fossil fuels. Reducing emission rates of toxic substances is central to debate on sustainable development but this can negatively affect economic growth.

The Dictionary of Human Geography defines development as "[p]rocesses of social change or [a change] to class and state projects to transform national economies".[12] This definition entails an understanding of economic development which is imperative when trying to understand the north–south divide.

Economic Development is a measure of progress in a specific economy. It refers to advancements in technology, a transition from an economy based largely on agriculture to one based on industry and an improvement in living standards.[13]

Other factors that are included in the conceptualization of what a developed country is include life expectancy and the levels of education, poverty and employment in that country.

Furthermore, in Regionalism Across the North-South Divide: State Strategies and Globalization, Jean Grugel states that the three factors that direct the economic development of states within the Global south is "élite behaviour within and between nation states, integration and cooperation within 'geographic' areas, and the resulting position of states and regions within the global world market and related political economic hierarchy."[14]

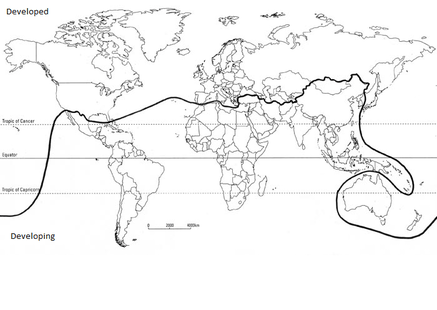

Brandt Line

The Brandt Line is a visual depiction of the north–south divide, proposed by West German former Chancellor Willy Brandt in the 1980s. It encircles the world at a latitude of approximately 30° North, passing between North and Central America, north of Africa and the Middle East, climbing north over China and Mongolia, but dipping south so as to include Australia and New Zealand in the "Rich North".

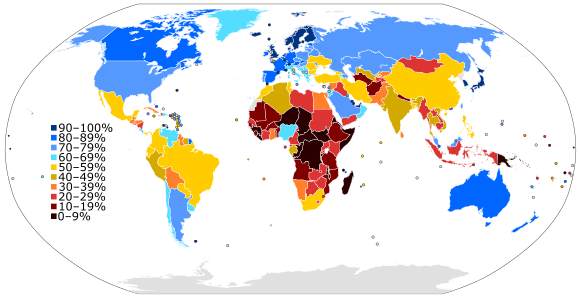

Digital and technological divide

The global digital divide is often characterised as corresponding to the north–south divide; however, Internet use, and especially broadband access, is now soaring in Asia compared with other continents. This phenomenon is partially explained by the ability of many countries in Asia to leapfrog older Internet technology and infrastructure, coupled with booming economies which allow vastly more people to get online.

Theories explaining the divide

The development disparity between the North and the South has sometimes been explained in historical terms. Dependency theory looks back on the patterns of colonial relations which persisted between the North and South and emphasizes how colonized territories tended to be impoverished by those relations.[8] Theorists of this school maintain that the economies of ex-colonial states remain oriented towards serving external rather than internal demand, and that development regimes undertaken in this context have tended to reproduce in underdeveloped countries the pronounced class hierarchies found in industrialized countries while maintaining higher levels of poverty.[8] Dependency theory is closely intertwined with Latin American Structuralism, the only school of development economics emerging from the Global South to be affiliated with a national research institute and to receive support from national banks and finance ministries.[15] The Structuralists defined dependency as the inability of a nation's economy to complete the cycle of capital accumulation without reliance on an outside economy.[16] More specifically, peripheral nations were perceived as primary resource exporters reliant on core economies for manufactured goods.[17] This led the Structuralists to advocate for import-substitution industrialization policies which aimed to replace manufactured imports with domestically made products.[15]

Uneven immigration patterns lead to inequality: in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries immigration was very common into areas previously less populated (North America, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Australia, New Zealand) from already technologically advanced areas (Germany, United Kingdom, France, Spain, Portugal). This facilitated an uneven diffusion of technological practices since only areas with high immigration levels benefited. Immigration patterns in the twenty-first century continue to feed this uneven distribution of technological innovation. People are eager to leave countries in the South to improve the quality of their lives by sharing in the perceived prosperity of the North. "South and Central Americans want to live and work in North America. Africans and Southwest Asians want to live and work in Europe. Southeast Asians want to live and work in North America and Europe".[18]

New Economic Geography explains development disparities in terms of the physical organization of industry, arguing that firms tend to cluster in order benefit from economies of scale and increase productivity which leads ultimately to an increase in wages.[19] The North has more firm clustering than the South, making its industries more competitive. It is argued that only when wages in the North reach a certain height, will it become more profitable for firms to operate in the South, allowing clustering to begin.

Challenges

%2C_Credit_Suisse.png)

The accuracy of the North–South divide has been challenged on a number of grounds. Firstly, differences in the political, economic and demographic make-up of countries tend to complicate the idea of a monolithic South.[4] Globalization has also challenged the notion of two distinct economic spheres. Following the liberalization of post-Mao China initiated in 1978, growing regional cooperation between the national economies of Asia has led to the growing decentralization of the North as the main economic power.[20] The economic status of the South has also been fractured. As of 2015, all but roughly the bottom 60 nations of the Global South were thought to be gaining on the North in terms of income, diversification, and participation in the world market.[19] Globalization has largely displaced the North–South divide as the theoretical underpinning of the development efforts of international institutions such as the IMF, World Bank, WTO, and various United Nations affiliated agencies, though these groups differ in their perceptions of the relationship between globalization and inequality.[9] Yet some remain critical of the accuracy of globalization as a model of the world economy, emphasizing the enduring centrality of nation-states in world politics and the prominence of regional trade relations.[17]

Future development

Some economists have argued that international free trade and unhindered capital flows across countries could lead to a contraction in the North–South divide. In this case more equal trade and flow of capital would allow the possibility for developing countries to further develop economically.[18]

As some countries in the South experience rapid development, there is evidence that those states are developing high levels of South–South aid.[21] Brazil, in particular, has been noted for its high levels of aid ($1 billion annually—ahead of many traditional donors) and the ability to use its own experiences to provide high levels of expertise and knowledge transfer.[21] This has been described as a "global model in waiting".[22]

The United Nations has also established its role in diminishing the divide between North and South through the Millennium Development Goals, all of which were to be achieved by 2015. These goals seek to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, achieve global universal education and healthcare, promote gender equality and empower women, reduce child mortality, improve maternal health, combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases, ensure environmental sustainability, and develop a global partnership for development.[23]

See also

International North–South divide

- South–South cooperation

- Non-Aligned Movement

- North–South Summit, the only North–South summit ever held, with 22 heads of state and government taking part

- North–South Centre, an institution of the Council of Europe, awarding the North–South Prize

- North–South model, in economics theory

- BRICS, CIVETS, MINT, VISTA

- Golden billion

- United Nations statistical divisions

- Sunshine countries

- Global South Development Magazine

National North–South divides

- Economy of Belgium § Regional differences

- Economy of Italy § North–South divide

- Northern and southern China

- Division of Korea

- North–South divide in Taiwan

- Mason–Dixon line (US)

- North–South divide in the United Kingdom

- North-south divide in India

Other

References

- Mimiko, Oluwafemi (2012). Globalization: The Politics of Global Economic Relations and International Business. Durham, N.C.: Carolina Academic. p. 47.

- Therien, Jean-Philippe (1999-08-01). "Beyond the North-South divide: The two tales of world poverty". Third World Quarterly. 20 (4): 723–742. doi:10.1080/01436599913523. ISSN 0143-6597.

- Therien, Jean-Philippe (2010). "Beyond the North-South divide: The two tales of world poverty". Third World Quarterly. 20 (4): 723–742. doi:10.1080/01436599913523. JSTOR 3993585.

- Tomlinson, B.R. (April 2003). "What was the Third World?". Journal of Contemporary History. 38 (2): 307–309. doi:10.1177/0022009403038002135.

- Dados, Nour; Connell, Raewyn (February 2012). "The Global South" (PDF). Contexts. 11 (1): 12–13. doi:10.1177/1536504212436479.

- Cox, Robert W. (Spring 1979). "Ideologies and the New International Economic Order: Reflections on Some Recent Literature". International Organization. 33 (2): 257–302. doi:10.1017/S0020818300032161. JSTOR 2706612.

- Stettner, Walter F. (Spring 1982). "The Brandt Commission Report: A Critical Appraisal". International Social Science Review. 57 (2): 67–81. JSTOR 41881303.

- Litonjua, M.D. (Spring 2012). "Third World/Global South: From Modernization, to Dependency/Liberation, to Postdevelopment". Journal of Third World Studies. 29 (1): 25–56 – via ProQuest.

- Thérien, Jean-Philippe (August 1999). "Beyond the North-South Divide: The Two Tales of World Poverty". Third World Quarterly. 20 (4): 723–742. doi:10.1080/01436599913523.

- Mimiko, N. Oluwafemi. Globalization: The Politics of Global Economic Relations and International Business. North Carolina: Carolina Academic Press, 2012. 22 & 47. Print.

- Preece, Julia (2009). "Lifelong learning and development: a perspective from the 'South'". Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. 39 (5): 585–599. doi:10.1080/03057920903125602.

- Gregory, Derek, Ron Johnston, Geraldine Pratt, Michael J. Watts, and Sarah Whatmore. The Dictionary of Human Geography. 5th. Wiley-Blackwell, 2009. Print.

- Economic development “implies progressive changes in the socio-economic structure of a country […] [a] change in technological and institutional organization of production as well as in distributive pattern of income”

- Grugel, Jean; Hout, Wil (1999-01-01). Regionalism Across the North-South Divide: State Strategies and Globalization. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415162128.

- Love, Joseph Leroy (2005). "The Rise and Decline of Economic Structuralism in Latin America: New Dimensions". Latin American Research Review. 40 (3): 100–125. doi:10.1353/lar.2005.0058. JSTOR 3662824.

- Caporaso, James A. (1980). "Dependency Theory: Continuities and Discontinuities in Development Studies". International Organization. 34 (4): 605–628. doi:10.1017/S0020818300018865.

- Herath, Dhammika (2008). "Development Discourse of the Globalists and Dependency Theorists: Do the Globalisation Theorists Rephrase and Reword the Central Concepts of the Dependency School?". Third World Quarterly. 29 (4): 819–834. doi:10.1080/01436590802052961.

- Reuveny, Rafael X.; Thompson, William R. (2007). "The North-South Divide and International Studies: A Symposium". International Studies Review. 9 (4): 556–564. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2486.2007.00722.x. JSTOR 4621859.

- Collier, Paul (2015). "Development Economics in Retrospect and Prospect". Oxford Review of Economic Policy. 31 (2): 242–258. doi:10.1093/oxrep/grv013 – via Oxford Academic.

- Golub, Philip S. (July 2013). "From the New International Economic Order to the G20: How the 'Global South' is Restructuring Global Capitalism from Within". Third World Quarterly. 34 (6): 1000–1015. doi:10.1080/01436597.2013.802505.

- Cabral and Weinstock 2010. Brazil: an emerging aid player. London: Overseas Development Institute

- Cabral, Lidia 2010. Brazil’s development cooperation with the South: a global model in waiting Archived 2011-04-30 at the Wayback Machine. London: Overseas Development Institute

- "United Nations Millennium Development Goals". www.un.org.

External links

- Global South Development Magazine, a free magazine on global south and international development issues

- Share The World's Resources: The Brandt Commission Report, a 1980 report by a commission led by Willy Brandt that popularized the terminology

- Brandt 21 Forum, a recreation of the original commission with an updated report (information on original commission at site)