Environmental impact of the energy industry

The environmental impact of the energy industry is diverse. Energy has been harnessed by human beings for millennia. Initially it was with the use of fire for light, heat, cooking and for safety, and its use can be traced back at least 1.9 million years.[3] In recent years there has been a trend towards the increased commercialization of various renewable energy sources.

Rapidly advancing technologies can potentially achieve a transition of energy generation, water and waste management, and food production towards better environmental and energy usage practices using methods of systems ecology and industrial ecology.[4][5]

Issues

Climate change

.svg.png)

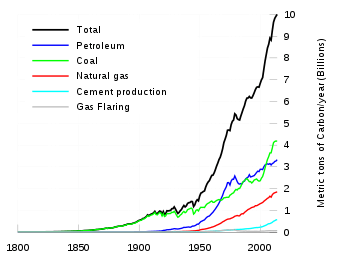

The scientific consensus on global warming and climate change is that it is caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, the majority of which comes from burning fossil fuels with deforestation and some agricultural practices being also major contributors.[6] A 2013 study showed that two thirds of the industrial greenhouse gas emissions are due to the fossil-fuel (and cement) production of just ninety companies around the world (between 1751 and 2010, with half emitted since 1986).[7][8]

Although there is a highly publicized denial of climate change, the vast majority of scientists working in climatology accept that it is due to human activity. The IPCC report Climate Change 2007: Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability predicts that climate change will cause shortages of food and water and increased risk of flooding that will affect billions of people, particularly those living in poverty.[9]

One measurement of greenhouse gas related and other Externality comparisons between energy sources can be found in the ExternE project by the Paul Scherrer Institut and the University of Stuttgart which was funded by the European Commission.[10] According to that study,[11] hydroelectric electricity produces the lowest CO2 emissions, wind produces the second-lowest, nuclear energy produces the third-lowest and solar photovoltaic produces the fourth-lowest.[11]

Similarly, the same research study (ExternE, Externalities of Energy), undertaken from 1995 to 2005 found that the cost of producing electricity from coal or oil would double over its present value, and the cost of electricity production from gas would increase by 30% if external costs such as damage to the environment and to human health, from the airborne particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, chromium VI and arsenic emissions produced by these sources, were taken into account. It was estimated in the study that these external, downstream, fossil fuel costs amount up to 1–2% of the EU's entire Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and this was before the external cost of global warming from these sources was even included.[12] The study also found that the environmental and health costs of nuclear power, per unit of energy delivered, was €0.0019/kWh, which was found to be lower than that of many renewable sources including that caused by biomass and photovoltaic solar panels, and was thirty times lower than coal at €0.06/kWh, or 6 cents/kWh, with the energy sources of the lowest external environmental and health costs associated with it being wind power at €0.0009/kWh.[13]

Biofuel use

Biofuel is defined as solid, liquid or gaseous fuel obtained from relatively recently lifeless or living biological material and is different from fossil fuels, which are derived from long-dead biological material. Various plants and plant-derived materials are used for biofuel manufacturing.

Bio-diesel

High use of bio-diesel leads to land use changes including deforestation.[14]

Firewood

Unsustainable firewood harvesting can lead to loss of biodiversity and erosion due to loss of forest cover. An example of this is a 40-year study done by the University of Leeds of African forests, which account for a third of the world's total tropical forest which demonstrates that Africa is a significant carbon sink. A climate change expert, Lee White states that "To get an idea of the value of the sink, the removal of nearly 5 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by intact tropical forests is at issue.

According to the U.N. the African continent is losing forest twice as fast as the rest of the world. "Once upon a time, Africa boasted seven million square kilometers of forest but a third of that has been lost, most of it to charcoal."[15]

Fossil fuel use

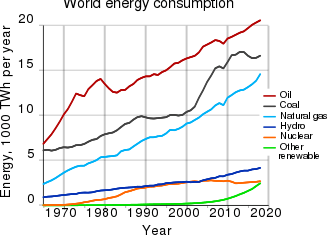

The three fossil fuel types are coal, petroleum and natural gas. It was estimated by the Energy Information Administration that in 2006 primary sources of energy consisted of petroleum 36.8%, coal 26.6%, natural gas 22.9%, amounting to an 86% share for fossil fuels in primary energy production in the world.[16]

In 2013 the burning of fossil fuels produced around 32 billion tonnes (32 gigatonnes) of carbon dioxide and additional air pollution. This caused negative externalities of $4.9 trillion due to global warming and health problems (> 150 $/ton carbon dioxide).[17] Carbon dioxide is one of the greenhouse gases that enhances radiative forcing and contributes to global warming, causing the average surface temperature of the Earth to rise in response, which climate scientists agree will cause major adverse effects.

Coal

The environmental impact of coal mining and burning is diverse.[18] Legislation passed by the U.S. Congress in 1990 required the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to issue a plan to alleviate toxic pollution from coal-fired power plants. After delay and litigation, the EPA now has a court-imposed deadline of March 16, 2011, to issue its report.

Petroleum

The environmental impact of petroleum is often negative because it is toxic to almost all forms of life. The possibility of climate change exists. Petroleum, commonly referred to as oil, is closely linked to virtually all aspects of present society, especially for transportation and heating for both homes and for commercial activities.

Gas

Natural gas is often described as the cleanest fossil fuel, producing less carbon dioxide per joule delivered than either coal or oil,[19] and far fewer pollutants than other fossil fuels. However, in absolute terms, it does contribute substantially to global carbon emissions, and this contribution is projected to grow. According to the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report,[20] in 2004 natural gas produced about 5,300 Mt/yr of CO2 emissions, while coal and oil produced 10,600 and 10,200 respectively (Figure 4.4); but by 2030, according to an updated version of the SRES B2 emissions scenario, natural gas would be the source of 11,000 Mt/yr, with coal and oil now 8,400 and 17,200 respectively. (Total global emissions for 2004 were estimated at over 27,200 Mt.)

In addition, natural gas itself is a greenhouse gas far more potent than carbon dioxide when released into the atmosphere but is released in smaller amounts.

Electricity generation

The environmental impact of electricity generation is significant because modern society uses large amounts of electrical power. This power is normally generated at power plants that convert some other kind of energy into electrical power. Each such system has advantages and disadvantages, but many of them pose environmental concerns.

Reservoirs

The environmental impact of reservoirs is coming under ever increasing scrutiny as the world demand for water and energy increases and the number and size of reservoirs increases. Dams and the reservoirs can be used to supply drinking water, generate hydroelectric power, increasing the water supply for irrigation, provide recreational opportunities and for flood control. However, adverse environmental and sociological impacts have also been identified during and after many reservoir constructions. Whether reservoir projects are ultimately beneficial or detrimental—to both the environment and surrounding human populations— has been debated since the 1960s and probably long before that. In 1960 the construction of Llyn Celyn and the flooding of Capel Celyn provoked political uproar which continues to this day. More recently, the construction of Three Gorges Dam and other similar projects throughout Asia, Africa and Latin America have generated considerable environmental and political debate.

Nuclear power

The environmental impact of nuclear power results from the nuclear fuel cycle, operation, and the effects of nuclear accidents.

The routine health risks and greenhouse gas emissions from nuclear fission power are significantly smaller than those associated with coal, oil and gas. However, there is a "catastrophic risk" potential if containment fails,[22] which in nuclear reactors can be brought about by over-heated fuels melting and releasing large quantities of fission products into the environment. The most long-lived radioactive wastes, including spent nuclear fuel, must be contained and isolated from humans and the environment for hundreds of thousands of years. The public is sensitive to these risks and there has been considerable public opposition to nuclear power. Despite this potential for disaster, normal fossil fuel related pollution is still considerably more harmful than any previous nuclear disaster.

The 1979 Three Mile Island accident and 1986 Chernobyl disaster, along with high construction costs, ended the rapid growth of global nuclear power capacity.[22] A further disastrous release of radioactive materials followed the 2011 Japanese tsunami which damaged the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant, resulting in hydrogen gas explosions and partial meltdowns classified as a Level 7 event. The large-scale release of radioactivity resulted in people being evacuated from a 20 km exclusion zone set up around the power plant, similar to the 30 km radius Chernobyl Exclusion Zone still in effect.

Wind power

The environmental impact of wind power when compared to the environmental impacts of fossil fuels, is relatively minor. According to the IPCC, in assessments of the life-cycle global warming potential of energy sources, wind turbines have a median value of between 12 and 11 (gCO

2eq/kWh) depending, respectively, on if offshore or onshore turbines are being assessed.[23][24] Compared with other low carbon power sources, wind turbines have some of the lowest global warming potential per unit of electrical energy generated.[25]

While a wind farm may cover a large area of land, many land uses such as agriculture are compatible with it, as only small areas of turbine foundations and infrastructure are made unavailable for use.[26][27]

There are reports of bird and bat mortality at wind turbines as there are around other artificial structures. The scale of the ecological impact may or may not be significant, depending on specific circumstances. Prevention and mitigation of wildlife fatalities, and protection of peat bogs, affect the siting and operation of wind turbines.

There are anecdotal reports of negative health effects from noise on people who live very close to wind turbines.[28] Peer-reviewed research has generally not supported these claims.[29]

Aesthetic aspects of wind turbines and resulting changes of the visual landscape are significant.[30] Conflicts arise especially in scenic and heritage protected landscapes.

Solar power

Geothermal power

Mitigation

Energy conservation

Energy conservation refers to efforts made to reduce energy consumption. Energy conservation can be achieved through increased efficient energy use, in conjunction with decreased energy consumption and/or reduced consumption from conventional energy sources.

Energy conservation can result in increased financial capital, environmental quality, national security, personal security, and human comfort. Individuals and organizations that are direct consumers of energy choose to conserve energy to reduce energy costs and promote economic security. Industrial and commercial users can increase energy use efficiency to maximize profit.

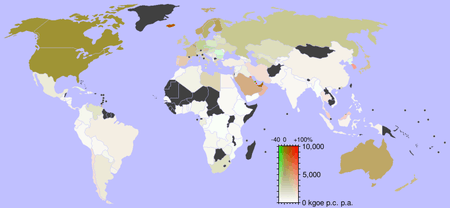

The increase of global energy use can also be slowed by tackling human population growth, by using non-coercive measures such as better provision of family planning services and by empowering (educating) women in developing countries.

Energy policy

Energy policy is the manner in which a given entity (often governmental) has decided to address issues of energy development including energy production, distribution and consumption. The attributes of energy policy may include legislation, international treaties, incentives to investment, guidelines for energy conservation, taxation and other public policy techniques.

See also

- Energetics

- Energy accounting

- Energy & Environment

- Energy economics

- Energy flow (ecology)

- Energy industry

- Energy quality

- Energy transformation

- Environmental impact of aviation

- Environmental impact of electricity generation

- Environmental impact of hydraulic fracturing

- Index of energy articles

- Industrial ecology

- List of energy storage projects

- List of environmental issues

- Low-carbon power

- Systems ecology

- The Venus Project

- Thermoeconomics

References

- BP: Workbook of historical data (xlsx), London, 2012

- "Energy Consumption: Total energy consumption per capita". Earth trends Database. World Resources Institute. Archived from the original on 12 December 2004. Retrieved 2011-04-21.

- Bowman, D. M. J. S; Balch, J. K; Artaxo, P; Bond, W. J; Carlson, J. M; Cochrane, M. A; d'Antonio, C. M; Defries, R. S; Doyle, J. C; Harrison, S. P; Johnston, F. H; Keeley, J. E; Krawchuk, M. A; Kull, C. A; Marston, J. B; Moritz, M. A; Prentice, I. C; Roos, C. I; Scott, A. C; Swetnam, T. W; Van Der Werf, G. R; Pyne, S. J (2009). "Fire in the Earth System". Science. 324 (5926): 481–4. Bibcode:2009Sci...324..481B. doi:10.1126/science.1163886. PMID 19390038.

- Kay, J. (2002). Kay, J.J. "On Complexity Theory, Exergy and Industrial Ecology: Some Implications for Construction Ecology." Archived 6 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine In: Kibert C., Sendzimir J., Guy, B. (eds.) Construction Ecology: Nature as the Basis for Green Buildings, pp. 72–107. London: Spon Press. Retrieved on: 2009-04-01.

- Baksh B., Fiksel J. (2003). "The Quest for Sustainability: Challenges for Process Systems Engineering" (PDF). American Institute of Chemical Engineers Journal. 49 (6): 1355. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2009.

- "Help finding information | US EPA".

- Douglas Starr, "The carbon accountant. Richard Heede pins much of the responsibility for climate change on just 90 companies. Others say that's a cop-out", Science, volume 353, issue 6302, 26 August 2016, pages 858–861.

- Richard Heede, "Tracing anthropogenic carbon dioxide and methane emissions to fossil fuel and cement producers, 1854–2010", Climatic Change, January 2014, volume 122, issue 1, pages 229–241 doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0986-y.

- "Billions face climate change risk". BBC NEWS Science/Nature. 6 April 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Rabl A.; et al. (August 2005). "Final Technical Report, Version 2" (PDF). Externalities of Energy: Extension of Accounting Framework and Policy Applications. European Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2012.

- "External costs of electricity systems (graph format)". ExternE-Pol. Technology Assessment / GaBE (Paul Scherrer Institut). 2005. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013.

- New research reveals the real costs of electricity in Europe

- ExternE-Pol, External costs of current and advanced electricity systems, associated with emissions from the operation of power plants and with the rest of the energy chain, final technical report. See figure 9, 9b and figure 11

- Gao, Yan (2011). "Working paper. A global analysis of deforestation due to biofuel development" (PDF). Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- Rowan, Anthea (25 September 2009). "Africa's burning charcoal problem". BBC NEWS Africa. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- "International Energy Annual 2006". Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- Ottmar Edenhofer, King Coal and the queen of subsidies. In: Science 349, Issue 6254, (2015), 1286, doi:10.1126/science.aad0674.

- "Environmental impacts of coal power: air pollution". Union of Concerned Scientists. 2009. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- Natural Gas and the Environment Archived 3 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (Working Group III Report, Chapter 4)

- Poulakis, Evangelos; Philippopoulos, Constantine (2017). "Photocatalytic treatment of automotive exhaust emissions". Chemical Engineering Journal. 309: 178–186. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2016.10.030.

- International Panel on Fissile Materials (September 2010). "The Uncertain Future of Nuclear Energy" (PDF). Research Report 9. p. 1.

- "IPCC Working Group III – Mitigation of Climate Change, Annex II I: Technology - specific cost and performance parameters" (PDF). IPCC. 2014. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 June 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- "IPCC Working Group III – Mitigation of Climate Change, Annex II Metrics and Methodology. pg 37 to 40,41" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2014.

- Begoña Guezuraga, Rudolf Zauner, Werner Pölz, Life cycle assessment of two different 2 MW class wind turbines, Renewable Energy 37 (2012) 37–44, p 37. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2011.05.008

- Why Australia needs wind power Archived 1 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Wind energy Frequently Asked Questions". British Wind Energy Association. Archived from the original on 19 April 2006. Retrieved 21 April 2006.

- Gohlke, Julia M; Hrynkow, Sharon H; Portier, Christopher J (2008). "Health, Economy, and Environment: Sustainable Energy Choices for a Nation". Environmental Health Perspectives. 116 (6): A236–7. doi:10.1289/ehp.11602. PMC 2430245. PMID 18560493.

- Hamilton, Tyler (15 December 2009). "Wind Gets Clean Bill of Health". Toronto Star. Toronto. pp. B1–B2. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- Thomas Kirchhoff (2014): Energiewende und Landschaftsästhetik. Versachlichung ästhetischer Bewertungen von Energieanlagen durch Bezugnahme auf drei intersubjektive Landschaftsideale, in: Naturschutz und Landschaftsplanung 46 (1), 10–16.

External links

- United Nations Development Programme – Environment and Energy for Sustainable Development

- Discussion of environmental cost of providing renewable energy – Environment impact of renewable energy technologies