Environmental globalization

Environmental globalization refers to the internationally coordinated practices and regulations (often in the form of international treaties) regarding environmental protection.[1][2] An example of environmental globalization would be the series of International Tropical Timber Agreement treaties (1983, 1994, 2006), establishing International Tropical Timber Organization and promoting sustainable management of tropical forests. Environmental globalization is usually supported by non-governmental organizations and governments of developed countries, but opposed by governments of developing countries which see pro-environmental initiatives as hindering their economic development.

Definitions and characteristics

Karl S. Zimmerer defined it as "the increased role of globally organized management institutions, knowledge systems and monitoring, and coordinated strategies aimed at resource, energy, and conservation issues."[1] Alan Grainger in turn wrote that it can be understood as "an increasing spatial uniformity and contentedness in regular environmental management practices".[2] Steven Yearley has referred to this concept as "globalization of environmental concern".[3] Grainger also cited a study by Clark (2000), which he noted was an early treatment of the concept, and distinguished three aspects of environmental globalization: "global flows of energy, materials and organisms; formulation and global acceptance of ideas about global environment; and environmental governance" (a growing web of institutions concerned with global environment).[4]

Environmental globalization is related to economic globalization, as economic development on a global scale has environmental impacts on such scale, which is of concern to numerous organizations and individuals.[2][5] While economic globalization has environmental impacts, those impacts should not be confused with the concept of environmental globalization.[4] In some regards, environmental globalization is in direct opposition to economic globalization, particularly when the latter is described as encouraging trade, and the former, as promoting pro-environment initiatives that are an impediment to trade.[6] For that reason, an environmental activist might be opposed to economic globalization, but advocate environmental globalization.[7]

History

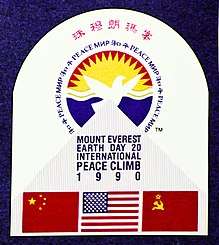

Grainger has discussed that environmental globalization in the context of international agreements on pro-environmental initiatives. According to him, precursors to modern environmental globalization can be found in the colonial era scientific forestry (research into how to create and restore forests).[8] Modern initiatives contributing to environmental globalization include the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment,[9] came from the World Bank 1980s requirements that development projects need to protect indigenous peoples and conserve biodiversity.[10] Other examples of such initiative include treaties such as the series of International Tropical Timber Agreement treaties (1983, 1994, 2006).[9][11] Therefore, unlike other main forms of globalization economic, political and cultural which were already strong in the 19th century, environmental globalization is a more recent phenomena, one that begun in earnest only in the later half of the 20th century.[12] Similarly, Steven Yearley states that it was around that time that the environmental movement started to organize on the international scale focus on the global dimension of the issues (the first Earth Day was celebrated on 1970).[6]

Supporters and opponents

According to Grainger, environmental globalization (in the form of pro-environmental international initiatives) is usually supported by various non-governmental organizations[11][13] and governments of developed countries, and opposed by governments of developing countries (Group of 77), which see pro-environmental initiatives as hindering their economic development.[10][14][15] Governmental resistance to environmental globalization takes form or policy ambiguity (exemplified by countries which sign international pro-environmental treaties and pass domestic pro-environmental laws, but then proceed to not enforce them[10][13]) and collective resistance in forums such as United Nations to projects that would introduce stronger regulations or new institutions policing environmental issues worldwide (such as opposition to the forest-protection agreement during the Earth Summit in 1992, which was eventually downgraded from a binding to a non-binding set of Forest Principles).[14][15]

World Trade Organization has also been criticized as focused on economic globalization (liberalizing trade) over concerns of environmental protection, which are seen as impeding the trade.[11][14][16][17] Steven Yearley states that WTO should not be described as "anti-environmental", but its decisions have major impact on environment worldwide, and they are based primarily on economic concerns, with environmental concerns being given secondary weight.[18]

See also

- Natural environment

- United Nations Climate Change conference

- International environmental organizations (category)

References

- Karl S. Zimmerer (2006). Globalization & New Geographies of Conservation. University of Chicago Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-226-98344-8.

- Alan Grainger (31 October 2013). "Environmental Globalization and Tropical Forests". In Jan Oosthoek; Barry K. Gills (eds.). The Globalization of Environmental Crisis. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-317-96896-2.

- Steve Yearly (15 April 2008). "Globalization and the Environment". In George Ritzer (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Globalization. John Wiley & Sons. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-470-76642-2.

- Grainger, Alan (1 January 2012). "Environmental Globalization". The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9780470670590.wbeog170. ISBN 9780470670590.

- John Benyon; David Dunkerley (1 May 2014). Globalization: The Reader. Routledge. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-136-78240-4.

- Steve Yearly (15 April 2008). "Globalization and the Environment". In George Ritzer (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Globalization. John Wiley & Sons. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-470-76642-2.

- Betty Dobratz; Lisa K Waldner; Timothy Buzzell (14 October 2015). Power, Politics, and Society: An Introduction to Political Sociology. Routledge. p. 346. ISBN 978-1-317-34529-9.

- Alan Grainger (31 October 2013). "Environmental Globalization and Tropical Forests". In Jan Oosthoek; Barry K. Gills (eds.). The Globalization of Environmental Crisis. Routledge. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-317-96896-2.

- Alan Grainger (31 October 2013). "Environmental Globalization and Tropical Forests". In Jan Oosthoek; Barry K. Gills (eds.). The Globalization of Environmental Crisis. Routledge. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-317-96896-2.

- Alan Grainger (31 October 2013). "Environmental Globalization and Tropical Forests". In Jan Oosthoek; Barry K. Gills (eds.). The Globalization of Environmental Crisis. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-317-96896-2.

- Alan Grainger (31 October 2013). "Environmental Globalization and Tropical Forests". In Jan Oosthoek; Barry K. Gills (eds.). The Globalization of Environmental Crisis. Routledge. p. 61. ISBN 978-1-317-96896-2.

- Peter N. Stearns (20 October 2009). Globalization in World History. Routledge. p. 159. ISBN 978-1-135-25993-8.

- Alan Grainger (31 October 2013). "Environmental Globalization and Tropical Forests". In Jan Oosthoek; Barry K. Gills (eds.). The Globalization of Environmental Crisis. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-317-96896-2.

- Alan Grainger (31 October 2013). "Environmental Globalization and Tropical Forests". In Jan Oosthoek; Barry K. Gills (eds.). The Globalization of Environmental Crisis. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-317-96896-2.

- Alan Grainger (31 October 2013). "Environmental Globalization and Tropical Forests". In Jan Oosthoek; Barry K. Gills (eds.). The Globalization of Environmental Crisis. Routledge. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-317-96896-2.

- Steve Yearly (15 April 2008). "Globalization and the Environment". In George Ritzer (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Globalization. John Wiley & Sons. p. 247. ISBN 978-0-470-76642-2.

- Steve Yearly (15 April 2008). "Globalization and the Environment". In George Ritzer (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Globalization. John Wiley & Sons. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-470-76642-2.

- Steve Yearly (15 April 2008). "Globalization and the Environment". In George Ritzer (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Globalization. John Wiley & Sons. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-470-76642-2.

Further reading

- William C. Clark (1 November 2000). "Environmental Globalization". In Joseph S. Nye; John D. Donahue (eds.). Governance in a Globalizing World. Visions of Governance for the 21st Century. pp. 86–108. ISBN 978-0-8157-9819-4.