Joseph Stiglitz

Joseph Eugene Stiglitz (/ˈstɪɡlɪts/; born February 9, 1943) is an American economist, public policy analyst, and a professor at Columbia University. He is a recipient of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences (2001) and the John Bates Clark Medal (1979).[2][3] He is a former senior vice president and chief economist of the World Bank and is a former member and chairman of the (US president's) Council of Economic Advisers.[4][5] He is known for his support of Georgist public finance theory[6][7][8] and for his critical view of the management of globalization, of laissez-faire economists (whom he calls "free-market fundamentalists"), and of international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

Joseph Stiglitz | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Chief Economist of the World Bank | |

| In office February 13, 1997 – February 2000 | |

| President | James Wolfensohn |

| Preceded by | Michael Bruno |

| Succeeded by | Nicholas Stern |

| 17th Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers | |

| In office June 28, 1995 – February 13, 1997 | |

| President | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Laura Tyson |

| Succeeded by | Janet Yellen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Joseph Eugene Stiglitz February 9, 1943 Gary, Indiana, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Hannaway (Divorced) Anya Schiffrin (2004–present) |

| Education | Amherst College (BA) Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MA, PhD) Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge St Catherine's College, Oxford |

| Academic career | |

| Field | Macroeconomics, public economics, information economics |

| School or tradition | Neo-Keynesian economics |

| Doctoral advisor | Robert Solow[1] |

| Doctoral students | Katrin Eggenberger |

| Influences | John Maynard Keynes, Robert Solow, James Mirrlees, Henry George |

| Contributions | |

| Information at IDEAS / RePEc | |

In 2000, Stiglitz founded the Initiative for Policy Dialogue (IPD), a think tank on international development based at Columbia University. He has been a member of the Columbia faculty since 2001, and received that university's highest academic rank (university professor) in 2003. He was the founding chair of the university's Committee on Global Thought. He also chairs the University of Manchester's Brooks World Poverty Institute. He is a member of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences. In 2009, the President of the United Nations General Assembly Miguel d'Escoto Brockmann, appointed Stiglitz as the chairman of the U.N. Commission on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System, where he oversaw suggested proposals and commissioned a report on reforming the international monetary and financial system.[9] He served as chair of the international Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, appointed by President Sarkozy of France, which issued its report in 2010, Mismeasuring our Lives: Why GDP doesn't add up,[10] and currently serves as co-chair of its successor, the High Level Expert Group on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. From 2011 to 2014, Stiglitz was president of the International Economic Association (IEA).[11] He presided over the organization of the IEA triennial world congress held near the Dead Sea in Jordan in June 2014.[12]

Stiglitz has received more than 40 honorary degrees, including from Cambridge and Harvard, and he has been decorated by several governments including Bolivia, Korea, Colombia, Ecuador, and most recently France, where he was appointed a member of the Legion of Honor, order Officer.

In 2011 Stiglitz was named by Time magazine as one of the 100 most influential people in the world.[13] Stiglitz's work focuses on income distribution from a Georgist perspective, asset risk management, corporate governance, and international trade. He is the author of several books, the latest being People, Power, and Profits (2019), The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe (2016), The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them (2015), Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity (2015), and Creating a Learning Society: A New Approach to Growth Development and Social Progress (2014).[14] He is also one of the 25 leading figures on the Information and Democracy Commission launched by Reporters Without Borders.[15]

Life and career

Stiglitz was born in Gary, Indiana, to a Jewish family[16]. His mother was Charlotte (née Fishman), a schoolteacher, and his father was Nathaniel David Stiglitz, an insurance salesman.[17][18] Stiglitz attended Amherst College, where he was active on the debate team and president of the student government.[19] During his senior year at Amherst College, he studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he later pursued graduate work.[19] In Summer 1965, he moved to the University of Chicago to do research under Hirofumi Uzawa who had received an NSF grant.[20] He studied for his PhD from MIT from 1966 to 1967, during which time he also held an MIT assistant professorship.[21] Stiglitz stated that the particular style of MIT economics suited him well, describing it as "simple and concrete models, directed at answering important and relevant questions."[2]

From 1966 to 1970 he was a research fellow at the University of Cambridge.[21] Stiglitz initially arrived at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge as a Fulbright Scholar in 1965, and he later won a Tapp Junior Research Fellowship at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge which was instrumental in shaping his understanding of Keynes and macroeconomic theory.[22] In subsequent years, he held academic positions at Yale, Stanford, and Princeton.[23] Since 2001, Stiglitz has been a professor at Columbia University, with appointments at the Business School, the Department of Economics and the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), and is editor of The Economists' Voice journal with J. Bradford DeLong and Aaron Edlin.[24]

He also gives classes for a double-degree program between Sciences Po Paris and École Polytechnique in 'Economics and Public Policy'. He has chaired The Brooks World Poverty Institute at the University of Manchester since 2005.[25][26] Stiglitz is widely considered a New-Keynesian economist,[27][28] although at least one economics journalist says his work cannot be so clearly categorised.[29]

Stiglitz has played a number of policy roles throughout his career. He served in the Clinton administration as the chair of the President's Council of Economic Advisers (1995–1997).[21] At the World Bank, he served as senior vice-president and chief economist from 1997–2000.[30] He was fired by the World Bank for expressing dissent with its policies.[31] He was a lead author of the 1995 Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which shared the Nobel Peace Prize in 2007.[32]

Stiglitz has advised American president Barack Obama, but has criticized the Obama Administration's financial-industry rescue plan. He said whoever designed the Obama administration's bank rescue plan is "either in the pocket of the banks or they're incompetent."[33]

In October 2008, he was asked by the President of the United Nations General Assembly to chair a commission drafting a report on the reasons for and solutions to the financial crisis.[34] In response, the commission produced the Stiglitz Report.

On July 25, 2011, Stiglitz participated in the "I Foro Social del 15M" organized in Madrid, expressing his support to 15M Movement protestors.[35]

Stiglitz was the president of the International Economic Association from 2011 to 2014.[36]

On September 27, 2015, the United Kingdom Labour Party announced that Stiglitz was to sit on its Economic Advisory Committee along with five other world leading economists.

Contributions to economics

After the 2018 mid-term elections in the United States he wrote a statement about the importance of economic justice to the survival of democracy worldwide.[37]

Risk aversion

After getting his PhD from M.I.T. in 1967, Stiglitz co-authored one of his first papers with Michael Rothschild for the Journal of Economic Theory in 1970. Stiglitz and Rothschild built upon works by economists such as Robert Solow on the concept of risk aversion. Stiglitz and Rothschild showed three plausible definitions of a variable X being 'more variable' than a variable Y were all equivalent - Y being equal to X plus noise, every risk averse agent preferring Y to X, and Y having more weight in its tails, and that none of these were always consistent with X having a higher statistical variance than Y - a commonly used definition at the time. In a second paper, they analyzed the theoretical consequences of risk aversion in various circumstances, such as an individual's savings decisions and a firm's production decisions.

Henry George theorem

Stiglitz made early contributions to a theory of public finance stating that an optimal supply of local public goods can be funded entirely through capture of the land rents generated by those goods (when population distributions are optimal). Stiglitz dubbed this the 'Henry George theorem' in reference to the radical classical economist Henry George who famously advocated for land value tax. The explanation behind Stiglitz's finding is that rivalry for public goods takes place geographically, so competition for access to any beneficial public good will increase land values by at least as much as its outlay cost. Furthermore, Stiglitz shows that a single tax on rents is necessary to provide the optimal supply of local public investment. Stiglitz also shows how the theorem could be used to find the optimal size of a city or firm.[38][39]

Information asymmetry

Stiglitz's most famous research was on screening, a technique used by one economic agent to extract otherwise private information from another. It was for this contribution to the theory of information asymmetry that he shared the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics[2] in 2001 "for laying the foundations for the theory of markets with asymmetric information" with George A. Akerlof and A. Michael Spence.

Much of Stiglitz' work on information economics demonstrates situations in which incomplete information prevents markets from achieving social efficiency. His paper with Andrew Weiss showed that if banks use interest rates to infer information about borrowers' types (adverse selection effect) or to encourage their actions following borrowing (incentive effect), then credit will be rationed below the optimal level, even in a competitive market.[40] Stiglitz and Rothschild showed that in an insurance market, firms have an incentive to undermine a 'pooling equilibrium', where all agents are offered the same full-insurance policy, by offering cheaper partial insurance that would only attractive to the low-risk types, meaning that a competitive market can only achieve partial coverage of agents.[41] Stiglitz and Grossman showed that trivially small information acquisition costs prevent financial markets from achieving complete informational efficiency, since agents will have an incentive to free-ride on others' information acquisition, and acquire this information indirectly by observing market prices.[42]

Monopolistic competition

Stiglitz, together with Avinash Dixit, created a tractable model of monopolistic competition that was an alternative to traditional perfect-competition models of general equilibrium. They showed that in the presence of increasing returns to scale, the entry of firms is socially too small.[43] The model was extended to show that when consumers have a preference for diversity, entry can be socially too large. The modelling approach was also influential in the fields of trade theory, and industrial organisation, and was used by Paul Krugman in his analysis of non comparative advantage trading patterns.[44]

Shapiro–Stiglitz efficiency wage model

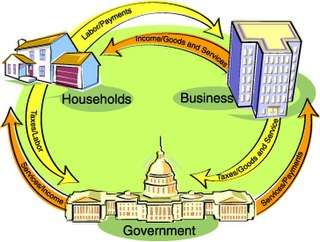

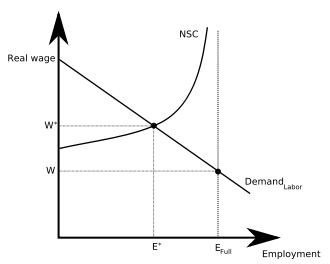

Stiglitz also did research on efficiency wages, and helped create what became known as the "Shapiro–Stiglitz model" to explain why there is unemployment even in equilibrium, why wages are not bid down sufficiently by job seekers (in the absence of minimum wages) so that everyone who wants a job finds one, and to question whether the neoclassical paradigm could explain involuntary unemployment.[45] An answer to these puzzles was proposed by Shapiro and Stiglitz in 1984: "Unemployment is driven by the information structure of employment".[45] Two basic observations undergird their analysis:

- Unlike other forms of capital, humans can choose their level of effort.

- It is costly for firms to determine how much effort workers are exerting.

A full description of this model can be found at the links provided.[46][47] Some key implications of this model are:

- Wages do not fall enough during recessions to prevent unemployment from rising. If the demand for labour falls, this lowers wages. But because wages have fallen, the probability of 'shirking' (workers not exerting effort) has risen. If employment levels are to be maintained, through a sufficient lowering of wages, workers will be less productive than before through the shirking effect. As a consequence, in the model, wages do not fall enough to maintain employment levels at the previous state, because firms want to avoid excessive shirking by their workers. So, unemployment must rise during recessions, because wages are kept 'too high'.

- Possible corollary: Wage sluggishness. Moving from one private cost of hiring (w∗) to another private cost of hiring (w∗∗) will require each firm to repeatedly re-optimize wages in response to shifting unemployment rate. Firms cannot cut wages until unemployment rises sufficiently (a coordination problem).

The outcome is never Pareto efficient.

- Each firm employs too few workers because it faces private cost of hiring rather than the social cost – which is equal to and in all cases. This means that firms do not "internalize" the "external" cost of unemployment – they do not factor how large-scale unemployment harms society when assessing their own costs. This leads to a negative externality as marginal social cost exceeds the firm's marginal cost (MSC = Firm's Private Marginal Cost + Marginal External Cost of increased social unemployment)

- There are also positive externalities: each firm increases the asset value of unemployment for all other firms when they hire during recessions. By creating hypercompetitive labor markets, all firms (the winners when laborers compete) experience an increase in value. However, this effect of increased valuation is very unapparent, because the first problem (the negative externality of sub-optimal hiring) clearly dominates since the 'natural rate of unemployment' is always too high.

Practical implications of Stiglitz' theories

The practical implications of Stiglitz' work in political economy and their economic policy implications have been subject to debate.[48] Stiglitz himself has evolved his political-economic discourse over time.[49]

Once incomplete and imperfect information is introduced, Chicago-school defenders of the market system cannot sustain descriptive claims of the Pareto efficiency of the real world. Thus, Stiglitz's use of rational-expectations equilibrium assumptions to achieve a more realistic understanding of capitalism than is usual among rational-expectations theorists leads, paradoxically, to the conclusion that capitalism deviates from the model in a way that justifies state action – socialism – as a remedy.[50]

The effect of Stiglitz's influence is to make economics even more presumptively interventionist than Samuelson preferred. Samuelson treated market failure as the exception to the general rule of efficient markets. But the Greenwald-Stiglitz theorem posits market failure as the norm, establishing "that government could potentially almost always improve upon the market's resource allocation." And the Sappington-Stiglitz theorem "establishes that an ideal government could do better running an enterprise itself than it could through privatization[51]

— Stiglitz 1994, p. 179.[50]

Objections to the adoption of positions suggested by Stiglitz's do not come from economics itself , but mostly from political scientists, especially in the field of sociology . As David L. Prychitko discusses in his "critique" to Whither Socialism? (see below), although Stiglitz' main economic insight seems generally correct , it still leaves open great constitutional questions such as how the coercive institutions of the government should be constrained and what the relation is between the government and civil society.[52]

Government

Clinton administration

Stiglitz joined the Clinton Administration in 1993,[53] serving first as a member during 1993–1995, and was then appointed Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers on June 28, 1995, in which capacity he also served as a member of the cabinet. He became deeply involved in environmental issues, which included serving on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and helping draft a new law for toxic wastes (which was never passed).

Stiglitz's most important contribution in this period was helping define a new economic philosophy, a "third way", which postulated the important, but limited, role of government, that unfettered markets often did not work well, but that government was not always able to correct the limitations of markets. The academic research that he had been conducting over the preceding 25 years provided the intellectual foundations for this "third way".

When President Bill Clinton was re-elected, he asked Stiglitz to continue to serve as Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers for another term. But he had already been approached by the World Bank to be its senior vice president for development policy and its chief economist, and he assumed that position after his CEA successor was confirmed on February 13, 1997.

As the World Bank began its ten-year review of the transition of the former Communist countries to the market economy it unveiled failures of the countries that had followed the International Monetary Fund (IMF) shock therapy policies – both in terms of the declines in GDP and increases in poverty – that were even worse than the worst that most of its critics had envisioned at the onset of the transition. Clear links existed between the dismal performances and the policies that the IMF had advocated, such as the voucher privatization schemes and excessive monetary stringency. Meanwhile, the success of a few countries that had followed quite different strategies suggested that there were alternatives that could have been followed. The US Treasury had put enormous pressure on the World Bank to silence his criticisms of the policies which they and the IMF had pursued.[54][55]

Stiglitz always had a poor relationship with Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers.[56] In 2000, Summers successfully petitioned for Stiglitz's removal, supposedly in exchange for World Bank President James Wolfensohn's re-appointment – an exchange that Wolfensohn denies took place. Whether Summers ever made such a blunt demand is questionable – Wolfensohn claims he would "have told him to *** himself".[57]

Stiglitz resigned from the World Bank in January 2000, a month before his term expired.[55] The Bank's president, James Wolfensohn, announced Stiglitz's resignation in November 1999 and also announced that Stiglitz would stay on as Special Advisor to the President, and would chair the search committee for a successor.

Joseph E. Stiglitz said today [Nov. 24, 1999] that he would resign as the World Bank's chief economist after using the position for nearly three years to raise pointed questions about the effectiveness of conventional approaches to helping poor countries.[58]

In this role, he continued criticism of the IMF, and, by implication, the US Treasury Department. In April 2000, in an article for The New Republic, he wrote:

They'll say the IMF is arrogant. They'll say the IMF doesn't really listen to the developing countries it is supposed to help. They'll say the IMF is secretive and insulated from democratic accountability. They'll say the IMF's economic 'remedies' often make things worse – turning slowdowns into recessions and recessions into depressions. And they'll have a point. I was chief economist at the World Bank from 1996 until last November, during the gravest global economic crisis in a half-century. I saw how the IMF, in tandem with the U.S. Treasury Department, responded. And I was appalled.

The article was published a week before the annual meetings of the World Bank and IMF and provoked a strong response. It proved too strong for Summers and, yet more lethally, Stiglitz's protector-of-sorts at the World Bank, Wolfensohn. Wolfensohn had privately empathised with Stiglitz's views, but this time was worried for his second term, which Summers had threatened to veto. Stanley Fischer, deputy managing director of the IMF, called a special staff meeting and informed at that gathering that Wolfensohn had agreed to fire Stiglitz. Meanwhile, the Bank's External Affairs department told the press that Stiglitz had not been fired, his post had merely been abolished.[59]

In a September 19, 2008 radio interview, with Aimee Allison and Philip Maldari on Pacifica Radio's KPFA 94.1 FM in Berkeley, US, Stiglitz implied that President Clinton and his economic advisors would not have backed the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) had they been aware of stealth provisions, inserted by lobbyists, that they overlooked.

Initiative for Policy Dialogue

In July 2000, Stiglitz founded the Initiative for Policy Dialogue (IPD), with support of the Ford, Rockefeller, McArthur, and Mott Foundations and the Canadian and Swedish governments, to enhance democratic processes for decision-making in developing countries and to ensure that a broader range of alternatives are on the table and more stakeholders are at the table.

Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress

At the beginning of 2008, Stiglitz chaired the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, also known as the Stiglitz-Sen-Fitoussi Commission, initiated by President Sarkozy of France. The Commission held its first plenary meeting on April 22–23, 2008, in Paris. Its final report was made public on September 14, 2009.[60]

Commission of Experts on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System

In 2009, Stiglitz chaired the Commission of Experts on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System which was convened by the President of the United Nations General Assembly "to review the workings of the global financial system, including major bodies such as the World Bank and the IMF, and to suggest steps to be taken by Member States to secure a more sustainable and just global economic order".[61] Its final report was released on September 21, 2009.[62][63]

Greek debt crisis

In 2010, Professor Stiglitz acted as an advisor to the Greek government during the Greek debt crisis. He appeared on Bloomberg TV for an interview on the risks of Greece defaulting, in which he stated that he was very confident that Greece would not default. He went on to say that Greece was under "speculative attack" and though it had "short-term liquidity problems ... and would benefit from Solidarity Bonds", the country was "on track to meet its obligations".

The next day, during a BBC interview, Stiglitz stated that "there's no problem of Greece or Spain meeting their interest payments". He argued nonetheless, that it would be desirable and needed for all of Europe to make a clear statement of belief in social solidarity and that they "stand behind Greece". Confronted with the statement: "Greece's difficulty is that the magnitude of debt is far greater than the capacity of the economy to service", Stiglitz replied, "That's rather absurd".

In 2012, Stiglitz described the European austerity plans as a "suicide-pact".[64]

Scotland

Since March 2012, Stiglitz has been a member of the Scottish Government's Fiscal Commission Working Group, which oversees the work to establish a fiscal and macro economic framework for an independent Scotland on behalf of the Scottish Council of Economic Advisers.

Together with Professors Andrew Hughes Hallett, Sir James Mirrlees and Frances Ruane, Stiglitz will "advise on the establishment of a credible Fiscal Commission which entrenches financial responsibility and ensures market confidence".[65]

Labour Party

In July 2015, Stiglitz endorsed Jeremy Corbyn's campaign in the Labour Party leadership election. He said: "I am not surprised at all that there is a demand for a strong anti-austerity movement around increased concern about inequality. The promises of New Labour in the UK and of the Clintonites in the US have been a disappointment."[66][67][68]

On September 27, 2015, it was announced that he had been appointed to the British Labour Party's Economic Advisory Committee, convened by Shadow Chancellor John McDonnell and reporting to Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn,[69] although he reportedly failed to attend the first meeting.[70]

Economic views

Market efficiency

For Stiglitz, there is no such thing as an invisible hand, in the sense that free markets lead to efficiency as if guided by unseen forces.[71] According to Stiglitz:[72]

Whenever there are "externalities" – where the actions of an individual have impacts on others for which they do not pay or for which they are not compensated – markets will not work well. But recent research has shown that these externalities are pervasive, whenever there is imperfect information or imperfect risk markets – that is always. The real debate today is about finding the right balance between the market and government. Both are needed. They can each complement each other. This balance will differ from time to time and place to place.

In an interview in 2007, Stiglitz explained further:[73]

The theories that I (and others) helped develop explained why unfettered markets often not only do not lead to social justice, but do not even produce efficient outcomes. Interestingly, there has been no intellectual challenge to the refutation of Adam Smith's invisible hand: individuals and firms, in the pursuit of their self-interest, are not necessarily, or in general, led as if by an invisible hand, to economic efficiency.

The preceding claim is based on Stiglitz's 1986 paper, "Externalities in Economies with Imperfect Information and Incomplete Markets",[74] which describes a general methodology to deal with externalities and for calculating optimal corrective taxes in a general equilibrium context. In the opening remarks for his prize acceptance at Aula Magna,[75] Stiglitz said:[76]

I hope to show that Information Economics represents a fundamental change in the prevailing paradigm within economics. Problems of information are central to understanding not only market economics but also political economy, and in the last section of this lecture, I explore some of the implications of information imperfections for political processes.

Support for anti-austerity movement in Spain

On July 25, 2011, Stiglitz participated in the "I Foro Social del 15M" organized in Madrid (Spain) expressing his support for the anti-austerity movement in Spain.[35] During an informal speech, he made a brief review of some of the problems in Europe and in the United States, the serious unemployment rate and the situation in Greece. "This is an opportunity for economic contribution social measures", argued Stiglitz, who made a critical speech about the way authorities are handling the political exit to the crisis. He encouraged those present to respond to the bad ideas, not with indifference, but with good ideas. "This does not work, you have to change it", he said.

Criticism of rating agencies

Stiglitz has been critical of rating agencies, describing them as the "key culprit" in the financial crisis, noting "they were the party that performed the alchemy that converted the securities from F-rated to A-rated. The banks could not have done what they did without the complicity of the rating agencies."[77]

Stiglitz co-authored a paper with Peter Orszag in 2002 titled "Implications of the New Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac Risk-Based Capital Standard" where they stated "on the basis of historical experience, the risk to the government from a potential default on GSE debt is effectively zero." However, "the risk-based capital standard ... may fail to reflect the probability of another Great Depression-like scenario."[78]

Criticism of Trans-Pacific Partnership and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership

Stiglitz warned that the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) presented "grave risks" and it "serves the interests of the wealthiest."[79][80]

Stiglitz also opposed the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) trade deal between the European Union (EU) and the United States, and has argued that the United Kingdom should consider its withdrawal from the EU in the 2016 referendum on the matter if TTIP passes, saying that "the strictures imposed by TTIP would be sufficiently averse to the functioning of government that it would make me think over again about whether membership of the EU was a good idea".[81][82]

Regulation

Stiglitz argues that relying solely on business self-interest as the means of achieving the well-being of society and economic efficiency is misleading, and that instead "What is needed is stronger norms, clearer understandings of what is acceptable – and what is not – and stronger laws and regulations to ensure that those that do not behave in ways that are consistent with these norms are held accountable".[83]

Land value tax (Georgism)

Stiglitz argues that land value tax would improve the efficiency and equity of agricultural economies. Stiglitz believes that societies should rely on a generalized Henry George principle to finance public goods, protect natural resources, improve land use, and reduce the burden of rents and taxes on the poor while increasing productive capital formation. Stiglitz advocates taxing "natural resource rents at as close to 100 percent as possible" and that a corollary of this principle is that polluters should be taxed for "activities that generate negative externalities."[84] Stiglitz therefore asserts that land value taxation is even better than its famous advocate Henry George thought.[85]

Views on the eurozone

In a September 2016 interview Stiglitz stated that "the cost of keeping the Eurozone together probably exceeds the cost of breaking it up."[86]

Views on free trade

Advice for the eurozone countries

In the 1990s, he wrote that "countries in North America and Europe should eliminate all tariffs and quotas (protectionist measures)".[87] He now advises the eurozone countries to control their trade balance with Germany by means of export/import certificates or "trade chits" (a protectionist measure).[88][89][90]

Citing Keynesian theory, he explains that trade surpluses are harmful: "John Maynard Keynes pointed out that surpluses lead to weak global aggregate demand – countries running surpluses exert a "negative externality" on trading partners. Indeed, Keynes believed it was surplus countries, far more than those in deficit, that posed a threat to global prosperity; he went so far as to advocate a tax on surplus countries".[91]

Stiglitz writes: "Germany's surplus means that the rest of Europe is in deficit. And the fact that these countries import more than they export contributes to the weakness of their economies". He thinks that surplus countries are getting richer at the expense of deficit countries. He notes that the euro is the cause of this deficit and that as the trade deficit declines GDP would rise and unemployment would fall: "The euro system means that Germany's exchange rate cannot increase compared to other euro area members. If the exchange rate were to rise, Germany would have more difficulty exporting and its economic model, based on strong exports, would cease. At the same time, the rest of Europe would export more, GDP would rise and unemployment would fall".[91]

He also thinks that the rest of the world should impose a carbon-adjustment tax (a protectionist measure) on American exports that do not comply with global standard.[92]

Advice for United States

Contrary to Keynesian theory and these analyses on the eurozone, he argues that the United States must not rebalance the trade account and can no longer apply protectionist measures to protect or recreate the well-paying manufacturing jobs. The United States must simply agree to be the "losers", saying: "The very Americans who have been among the losers of globalization stand to be among the losers of a reversal of globalization. History cannot be put into reverse".[93]

However, contrary to these statements, he admits that as the trade deficit declines "GDP would rise and unemployment would fall", further stating: "...the fact that these countries are importing more than they are exporting contributes to their weak economies.".[91] He notes that trade deficits caused by free trade destroy manufacturing jobs: the increase in the "value of the dollar will lead to larger trade deficits and fewer manufacturing jobs".[94]

Contrary to most economists historians, who argue that tariffs have played only a minor role or not at all in the Great Depression,[95][96][97] Stiglitz thinks that the United States should not protect its economy because tariffs contributed to the Great Depression: "Following that, U.S. exports fell by some 50 percent—contributing to our Great Depression".[93]

He denounces neoliberalism[98] but yet advises the United States to pursue free trade (deregulation or liberalization of foreign trade)[99] which is considered to be a constitutive policy of neoliberalism.[100]

According to him, it is not China (which has a large trade surplus) that makes "trade war", but the United States (which has a large trade deficit). He defends China's trade surpluses at the expense of the United States and he advises China to take sanctions against the United States. He believes that China should "react with strength and intelligence" and hit the United States "where it hurts economically and politically" if the United States tries to protect its industry and rebalance its trade account through tariffs, saying: "For example, cutbacks in purchases by China will lead to more unemployment in congressional districts that are vulnerable, influential, or both".[93] ... China can retaliate anywhere it chooses, such as by using trade restrictions to target jobs in the congressional districts of those who support US tariffs.[98] ... China may be more effective in targeting its retaliation to cause acute political pain. ... It's anybody's guess who can stand the pain better. Will it be the US, where ordinary citizens have already suffered for so long, or China, which, despite troubled times, has managed to generate growth in excess of 6%?".[101]

About China, he writes that the decline in exports is not prejudicial if China replaces "export dependence to a model of growth driven by domestic demand", therefore it's not the involvement in international trade per se that brings economic growth, but rather the access to strong demand. And it is not the level of exports that matters but rather the trade balance (gap between imports and exports). Regarding the United States, he writes the opposite: "Walking away from globalization may reduce our imports, but it will also reduce exports in tandem. And, almost surely, jobs will be destroyed faster than they will be created: there may even be fewer net manufacturing jobs". If the United States tries to control the movement of goods, "they surely will lose".[93]

In early 2017, he wrote that "the American middle class is indeed the loser of globalization" and "China, with its large emerging middle class, is among the big beneficiaries of globalization". "Thanks to globalisation, in terms of purchasing-power parity, China actually has already become the largest economy in the world in September 2015".[93] However, he then changed his mind and argued that the fall in wages and the disappearance of well-paid jobs in the United States, are not due to globalization, but are only inevitable collateral damage to the march of economic progress and technological innovation: "The United States can only push for advanced manufacturing, which requires higher skill sets and employs fewer people. Rising inequality, meanwhile, will continue ...".[98] Finally, he changed his mind again in late 2017 and wrote that the drop in wages in the United States, is not a normal process and is solely due to the actions of multinational companies, not to the trade account imbalances between countries caused by free trade: "It was an agenda written by and for large multinational companies, at the expense of workers". So it is no longer the surplus countries that have benefited from free trade, but only companies.[94]

In 2016, he said he believes that the economic situation of the United States is critical: "As the economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton showed in their study published in December 2015, life expectancy among middle-age white Americans is declining, as rates of suicides, drug use, and alcoholism increase. A year later, the National Center for Health Statistics reported that life expectancy for the country as a whole has declined for the first time in more than 20 years."[98] ... With the incomes of the bottom 90% having stagnated for close to a third of a century (and declining for a significant proportion), the health data simply confirmed that things were not going well for swaths of the country".[101] However, he changed his mind again in 2017 and now thinks that the effect of globalization on the American economy is not so serious today: "Yes, America faces a variety of problems—it always has, and what nation doesn't?".[93]

Books

Along with his technical economic publications (he has published over 300 technical articles), Stiglitz is the author of books on issues from patent law to abuses in international trade.

Whither Socialism? (1994)

Whither Socialism? is based on Stiglitz's Wicksell Lectures, presented at the Stockholm School of Economics in 1990 and presents a summary of information economics and the theory of markets with imperfect information and imperfect competition, as well as being a critique of both free market and market socialist approaches (see Roemer critique, op. cit.). Stiglitz explains how the neoclassical, or Walrasian model ("Walrasian economics" refers to the result of the process which has given birth to a formal representation of Adam Smith's notion of the "invisible hand", along the lines put forward by Léon Walras and encapsulated in the general equilibrium model of Arrow–Debreu), may have wrongly encouraged the belief that market socialism could work. Stiglitz proposes an alternative model, based on the information economics established by the Greenwald–Stiglitz theorems.

One of the reasons Stiglitz sees for the critical failing in the standard neoclassical model, on which market socialism was built, is its failure to consider the problems that arise from lack of perfect information and from the costs of acquiring information. He also identifies problems arising from its assumptions concerning completeness.[102]

Globalization and Its Discontents (2002)

In Globalization and Its Discontents, Stiglitz argues that what are often called "developing economies" are, in fact, not developing at all, and puts much of the blame on the IMF.

Stiglitz bases his argument on the themes that his decades of theoretical work have emphasized: namely, what happens when people lack the key information that bears on the decisions they have to make, or when markets for important kinds of transactions are inadequate or don't exist, or when other institutions that standard economic thinking takes for granted are absent or flawed. Stiglitz stresses the point: "Recent advances in economic theory" (in part referring to his own work) "have shown that whenever information is imperfect and markets incomplete, which is to say always, and especially in developing countries, then the invisible hand works most imperfectly." As a result, Stiglitz continues, governments can improve the outcome by well-chosen interventions. Stiglitz argues that when families and firms seek to buy too little compared to what the economy can produce, governments can fight recessions and depressions by using expansionary monetary and fiscal policies to spur the demand for goods and services. At the microeconomic level, governments can regulate banks and other financial institutions to keep them sound. They can also use tax policy to steer investment into more productive industries and trade policies to allow new industries to mature to the point at which they can survive foreign competition. And governments can use a variety of devices, ranging from job creation to manpower training to welfare assistance, to put unemployed labor back to work and cushion human hardship.

Stiglitz complains bitterly that the IMF has done great damage through the economic policies it has prescribed that countries must follow in order to qualify for IMF loans, or for loans from banks and other private-sector lenders that look to the IMF to indicate whether a borrower is creditworthy. The organization and its officials, he argues, have ignored the implications of incomplete information, inadequate markets, and unworkable institutions – all of which are especially characteristic of newly developing countries. As a result, Stiglitz argues, the IMF has often called for policies that conform to textbook economics but do not make sense for the countries to which the IMF is recommending them. Stiglitz seeks to show that these policies have been disastrous for the countries that have followed them.

The Roaring Nineties (2003)

The Roaring Nineties is Stiglitz' analysis of the boom and bust of the 1990s. Presented from an insider's point of view, firstly as chair of President Clinton's Council of Economic Advisors, and later as chief economist of the World Bank, it continues his argument on how misplaced faith in free-market ideology led to the global economic issues of today, with a perceptive focus on US policies.

New Paradigm for Monetary Economics (2003)

Fair Trade for All (2005)

In Fair Trade for All, authors Stiglitz and Andrew Charlton argue that it is important to make the trading world more development friendly.[103] The idea is put forth that the present regime of tariffs and agricultural subsidies is dominated by the interests of former colonial powers and needs to change. The removal of the bias toward the developed world will be beneficial to both developing and developed nations. The developing world is in needs of assistance, and this can only be achieved when developed nations abandon mercantilist based priorities and work towards a more liberal world trade regime.[104]

Making Globalization Work (2006)

Making Globalization Work surveys the inequities of the global economy, and the mechanisms by which developed countries exert an excessive influence over developing nations. Dr. Stiglitz argues that through tariffs, subsidies, an over-complex patent system and pollution, the world is being both economically and politically destabilised. Stiglitz argues that strong, transparent institutions are needed to address these problems. He shows how an examination of incomplete markets can make corrective government policies desirable.

Stiglitz is an exception to the general pro-globalisation view of professional economists, according to economist Martin Wolf.[105] Stiglitz argues that economic opportunities are not widely enough available, that financial crises are too costly and too frequent, and that the rich countries have done too little to address these problems. Making Globalization Work[106] has sold more than two million copies.

Stability with Growth (2006)

In Stability with Growth: Macroeconomics, Liberalization and Development, Stiglitz, José Antonio Ocampo (United Nations Under-Secretary-General for Economic and Social Affairs, until 2007), Shari Spiegel (Managing Director, Initiative for Policy Dialogue – IPD), Ricardo Ffrench-Davis (Main Adviser, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean – ECLAC) and Deepak Nayyar (Vice Chancellor, University of Delhi) discuss the current debates on macroeconomics, capital market liberalization and development, and develop a new framework within which one can assess alternative policies. They explain their belief that the Washington Consensus has advocated narrow goals for development (with a focus on price stability) and prescribed too few policy instruments (emphasizing monetary and fiscal policies), and places unwarranted faith in the role of markets. The new framework focuses on real stability and long-term sustainable and equitable growth, offers a variety of non-standard ways to stabilize the economy and promote growth, and accepts that market imperfections necessitate government interventions. Policy-makers have pursued stabilization goals with little concern for growth consequences, while trying to increase growth through structural reforms focused on improving economic efficiency. Moreover, structural policies, such as capital market liberalization, have had major consequences for economic stability. This book challenges these policies by arguing that stabilization policy has important consequences for long-term growth and has often been implemented with adverse consequences. The first part of the book introduces the key questions and looks at the objectives of economic policy from different perspectives. The third part presents a similar analysis for capital market liberalization.

The Three Trillion Dollar War (2008)

The Three Trillion Dollar War (co-authored with Linda Bilmes) examines the full cost of the Iraq War, including many hidden costs. The book also discusses the extent to which these costs will be imposed for many years to come, paying special attention to the enormous expenditures that will be required to care for very large numbers of wounded veterans. Stiglitz was openly critical of George W. Bush at the time the book was released.[107]

Freefall (2010)

In Freefall: America, Free Markets, and the Sinking of the World Economy, Stiglitz discusses the causes of the 2008 recession/depression and goes on to propose reforms needed to avoid a repetition of a similar crisis, advocating government intervention and regulation in a number of areas. Among the policy-makers he criticises are George W. Bush, Larry Summers, and Barack Obama.[108]

The Price of Inequality (2012)

From the jacket: As those at the top continue to enjoy the best health care, education, and benefits of wealth, they often fail to realize that, as Joseph E. Stiglitz highlights, "their fate is bound up with how the other 99 percent live ... It does not have to be this way. In The Price of Inequality Stiglitz lays out a comprehensive agenda to create a more dynamic economy and fairer and more equal society"

The book received the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights 2013 Book Award, given annually to the book that "most faithfully and forcefully reflects Robert Kennedy's purposes – his concern for the poor and the powerless, his struggle for honest and even-handed justice, his conviction that a decent society must assure all young people a fair chance, and his faith that a free democracy can act to remedy disparities of power and opportunity."[109]

Creating a Learning Society: A New Approach to Growth, Development, and Social Progress (2014)

Creating a Learning Society, (co authored with Bruce C. Greenwald), cast light on the significance of this insight for economic theory and policy. Taking as a starting point Kenneth J. Arrow's 1962 paper "Learning by Doing", they explain why the production of knowledge differs from that of other goods and why market economies alone typically do not produce and transmit knowledge efficiently. Closing knowledge gaps and helping laggards learn are central to growth and development. But creating a learning society is equally crucial if we are to sustain improved living standards in advanced countries.

The Great Divide: Unequal Societies and What We Can Do About Them (2015)

From the jacket: In The Great Divide, Joseph E. Stiglitz expands on the diagnosis he offered in his best-selling book The Price of Inequality and suggests ways to counter America's growing problem. Stiglitz argues that inequality is a choice – the cumulative result of unjust policies and misguided priorities.

The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe (2016)

People, Power and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent (2019)

Measuring What Counts; The Global Movement for Well-Being (2019)

Stiglitz and his coauthors point out that the interrelated crises of environmental degradation and human suffering of our current age demonstrate that "something is fundamentally wrong with the way we assess economic performance and social progress." They argue that using GDP as the chief measure of our economic health does not provide an accurate assessment of the economy or the state of the world and the people living in it.[110][111]

Papers and conferences

Stiglitz wrote a series of papers and held a series of conferences explaining how such information uncertainties may have influence on everything from unemployment to lending shortages. As the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers during the first term of the Clinton Administration and former chief economist at the World Bank, Stiglitz was able to put some of his views into action. For example, he was an outspoken critic of quickly opening up financial markets in developing countries. These markets rely on access to good financial data and sound bankruptcy laws, but he argued that many of these countries didn't have the regulatory institutions needed to ensure that the markets would operate soundly.

Awards and honors

In addition to being awarded the Nobel Memorial prize, Stiglitz has over 40 honorary doctorates and at least eight honorary professorships as well as an honorary deanship.[112][113][114]

He received the 2010 Gerald Loeb Awards for Commentary for "Capitalist Fools and Wall Street's Toxic Message".[115]

In 2011, he was named by Foreign Policy magazine on its list of top global thinkers.[116] In February 2012, he was awarded the Legion of Honor, in the rank of Officer, by the French ambassador in the United States François Delattre.[117] Stiglitz was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 2009.[118] Stiglitz was awarded the 2018 Sydney Peace Prize.[119]

Personal life

Stiglitz married Jane Hannaway in 1978; the couple later divorced.[120][121] He got married for the third time on October 28, 2004 to Anya Schiffrin, who works at the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University.[122] He has four children and three grandchildren.

Selected bibliography

Books

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Uzawa, Hirofumi (1969). Readings in the modern theory of economic growth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The M.I.T. Press. ISBN 9780262190558.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Atkinson, Anthony B. (1980). Lectures on public economics. London New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co. ISBN 9780070841055.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Newbery, David M.G. (1981). The theory of commodity price stabilization: a study in the economics of risk. Oxford Oxford New York: Clarendon Press Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198284178.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1989). The economic role of the state. Oxford, UK Cambridge, Massachusetts, US: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9780631171355.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Boadway, Robin (1994). Economics and the Canadian economy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393965117.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1994). Whither socialism?. Cambridge, Massachusetts, US: MIT Press. ISBN 9780262691826.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2000). Economics of the public sector (3rd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393966510.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Meier, Gerald M. (2001). Frontiers of development economics: the future in perspective. Washington, D.C. Oxford New York: World Bank Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195215922.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Holzmann, Robert (2001). New ideas about old age security: toward sustainable pension systems in the 21st century. Washington, DC: World Bank. ISBN 9780821348222.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Yusuf, Shahid (2001). Rethinking the East Asia miracle. Washington, D.C. New York: World Bank Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195216004.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2001). Chang, Ha-Joon (ed.). Joseph Stiglitz and the World Bank: the rebel within. London, England: Anthem Press. ISBN 9781898855538.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Sah, Raaj K. (1992). Peasants versus city-dwellers: taxation and the burden of economic development. Oxford New York: Clarendon Press Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199253579. (Reprinted 2005.)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2002). Globalization and its discontents. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393051247.

- Stiglitz, Joseph; Greenwald, Bruce (2003). Towards a new paradigm in monetary economics. The Raffaele Mattioli Lecture Series. Cambridge, UK and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521810340.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2003). The roaring nineties: a new history of the world's most prosperous decade. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393058529.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2004). The development round of trade negotiations in the aftermath of Cancún. London, UK: Commonwealth Secretariat. ISBN 9780850928013.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Charlton, Andrew (2005). Fair trade for all: how trade can promote development. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199290901.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Walsh, Carl E. (2006). Economics (4th ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393926224.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Walsh, Carl E. (2006). Principles of macroeconomics (4th ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393926248.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Ocampo, José Antonio; Ffrench-Davis, Ricardo; Nayyar, Deepak; Spiegel, Shari (2006). Stability with growth: macroeconomics, liberalization and development. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199288144.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2006). Making globalization work. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393061222.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Bilmes, Linda (2008). The three trillion dollar war: the true cost of the Iraq conflict. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393067019.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Ocampo, José Antonio; Griffith-Jones, Stephany (2010). Time for a visible hand: lessons from the 2008 world financial crisis. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199578818.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2010). The Stiglitz report: reforming the international monetary and financial systems in the wake of the global crisis. New York, New York London: The New Press. ISBN 9781595585202.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Sen, Amartya; Fitoussi, Jean-Paul (2010). Mismeasuring our lives: why GDP doesn't add up: the report. New York: New Press: Distributed by Perseus Distribution. ISBN 9781595585196.

- Stiglitz, Joseph (2010). Freefall: America, free markets, and the sinking of the world economy. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393338959.

- Also as: Stiglitz, Joseph (2010). Freefall: free markets and the sinking of the global economy. London: Penguin. ISBN 9780141045122.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2012). The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393088694.

- Stiglitz, Joseph; Greenwald, Bruce C. (2014). Creating a learning society: a new approach to growth, development, and social progress. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231152143.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2015). The great divide: unequal societies and what we can do about them. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393248579.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Greenwald, Bruce C. (2015). Creating a learning society: a new approach to growth, development, and social progress. Columbia: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231175494.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2016). The Euro: And its Threat to the Future of Europe. Allen Lane. ISBN 9780241258156.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2019). People, Power and Profits: Progressive Capitalism for an Age of Discontent. Allen Lane. ISBN 9780241399231.

- Stiglitz, Joseph; Fitoussi, Jean-Paul; Durand, Martine (19 November 2019). Measuring What Counts; The Global Movement for Well-Being (Paper ed.). New York: The New Press. ISBN 978-1-62097-569-5. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

Book chapters

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1989), "Principal and agent", in Eatwell, John; Milgate, Murray; Newman, Peter K. (eds.), The New Palgrave: allocation, information, and markets, New York: Norton, ISBN 9780393958546.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1993), "Market socialism and neoclassical economics", in Bardhan, Pranab; Roemer, John E. (eds.), Market socialism: the current debate, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195080490.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2009), "Regulation and failure", in Moss, David A.; Cisternino, John A. (eds.), New perspectives on regulation, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Tobin Project, pp. 11–23, ISBN 9780982478806.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Pdf version.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2009), "Simple formulae for optional income taxation and the measurement of inequality", in Kanbur, Ravi; Basu, Kaushik (eds.), Arguments for a better world: essays in honor of Amartya Sen | Volume I: Ethics, welfare, and measurement, Oxford New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 535–66, ISBN 9780199239115.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Selected scholarly articles

1970–1979

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Rothschild, Michael (September 1970). "Increasing risk: I. a definition". Journal of Economic Theory. Elsevier. 2 (3): 225–43. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(70)90038-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Rothschild, Michael (March 1971). "Increasing risk: II. Its economic consequences". Journal of Economic Theory. Elsevier. 3 (1): 66–84. doi:10.1016/0022-0531(71)90034-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (May 1974). "Alternative theories of wage determination and unemployment in LDC's: the labor turnover model". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Oxford Journals. 88 (2): 194–227. doi:10.2307/1883069. JSTOR 1883069.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (April 1974). "Incentives and risk sharing in sharecropping" (PDF). Review of Economic Studies. Oxford Journals. 41 (2): 219–55. doi:10.2307/2296714. JSTOR 2296714.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Rothschild, Michael (November 1976). "Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: an essay on the economics of imperfect information". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. Oxford Journals. 90 (4): 629–49. doi:10.2307/1885326. JSTOR 1885326.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Dixit, Avinash K. (June 1977). "Monopolistic competition and optimum product diversity". The American Economic Review. American Economic Association via JSTOR. 67 (3): 297–308. JSTOR 1831401.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Newbery, David M.G. (December 1979). "The theory of commodity price stabilisation rules: welfare impacts and supply responses". The Economic Journal. Royal Economic Society via JSTOR. 89 (356): 799–817. doi:10.2307/2231500. JSTOR 2231500.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

1980–1989

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Weiss, Andrew (June 1981). "Credit rationing in markets with imperfect information". The American Economic Review. American Economic Association via JSTOR. 71 (3): 393–410. JSTOR 1802787.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Pdf version.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Weiss, Andrew (1983). "Incentive Effects of Terminations: Applications to the Credit and Labor Markets". American Economic Review. 73 (5): 912–927.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Newbery, David M.G. (January 1984). "Pareto inferior trade". Review of Economic Studies. Oxford Journals. 51 (1): 1–12. doi:10.2307/2297701. JSTOR 2297701.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (March 1987). "The causes and consequences of the dependence of quality on price". The American Economic Review. American Economic Association via JSTOR. 25 (1): 1–48. JSTOR 2726189.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

1990–1999

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Greenwald, Bruce (Winter 1993). "New and old Keynesians". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. American Economic Association. 7 (1): 23–44. doi:10.1257/jep.7.1.23.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (Winter 1993). "Post Walrasian and Post Marxian economics". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. American Economic Association. 7 (1): 109–14. doi:10.1257/jep.7.1.109.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (August 1996). "Some lessons from the East Asian miracle". World Bank Research Observer. World Bank. 11 (2): 151–77. doi:10.1093/wbro/11.2.151.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Uy, Marilou (August 1996). "Financial markets, public policy, and the East Asian miracle" (PDF). World Bank Research Observer. World Bank. 11 (2): 249–76. doi:10.1093/wbro/11.2.249.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (September 1997). "Georgescu-Roegen versus Solow/Stiglitz". Ecological Economics. ScienceDirect. 22 (3): 269–70. doi:10.1016/S0921-8009(97)00092-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- See also: Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and Robert Solow

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (March 1998). "Redefining the role of the state – What should it do? How should it do it? And how should these decisions be made?". Paper Presented at the Tenth Anniversary of MITI Research Institute, Tokyo.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Pdf version.

- Also as: Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2001), "Redefining the role of the state – What should it do? How should it do it? And how should these decisions be made?", Joseph Stiglitz and the World Bank: the rebel within, by Stiglitz, Joseph E., Chang, Ha-Joon (ed.), London, England: Anthem Press, pp. 94–126, ISBN 9781898855538.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

2000–2009

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (Spring 1998). "Distinguished lecture on economics in government: the private uses of public interests: incentives and institutions". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. American Economic Association. 12 (2): 3–22. doi:10.1257/jep.12.2.3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (May 18, 2007). "Prizes, not patents". Post-Autistic Economics Review. World Economics Association. 42: 48–50.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

2010 onwards

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (May 28, 2014). "Reforming taxation to promote growth and equity". White Paper. Roosevelt Institute.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Pdf version.

Articles in popular press

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. "Joseph E. Stiglitz". Project Syndicate. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (17 April 2000). "What I learned at the world economic crisis: the insider" (PDF). The New Republic. Chris Hughes.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- See also: Wade, Robert (January–February 2001). "Showdown at the World Bank". New Left Review. New Left Review. II (7): 124–37.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Orszag, Peter R.; Orszag, Jonathan M. (March 2, 2002). "Implications of the new Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac risk-based capital standard" (PDF). Fannie Mae Press. Fannie Mae. I (2): 1–10. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2009.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (Fall 2003). "Information and the change in the paradigm in economics, part 1". The American Economist. Omicron Delta Epsilon. 47 (2): 6–26. doi:10.1177/056943450304700202. JSTOR 25604277. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (Spring 2004). "Information and the change in the paradigm in economics, part 2". The American Economist. Omicron Delta Epsilon. 48 (1): 17–49. doi:10.1177/056943450404800103. JSTOR 25604291. Archived from the original on April 7, 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (December 2007). "The economic consequences of Mr. Bush". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Bilmes, Linda J. (January 2009). "Report: the $10 trillion hangover: paying the price for eight years of Bush". Harper's Magazine. Harper's Magazine Foundation. 318 (1904).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Non-subscription version.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (January 2009). "Capitalist fools". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph (June 12, 2009). "America's socialism for the rich". The Guardian. London.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (July 2009). "Wall Street's toxic message". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (April 22, 2010). "The Non-Existent Hand". London Review of Books. 32 (8): 17–18. Retrieved February 14, 2011.

- Review of the book: Skidelsky, Robert (2009). Keynes: the return of the master. Allen Lane. ISBN 9781846142581.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (May 2011). "Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (July 12, 2011). "The ideological crisis of Western capitalism". Social Europe.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (January 2013). "The post-crisis crises". CFO Insight Magazine. Euro Treasurer.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (April 2013). "The promise of abenomics". CFO Insight Magazine. Euro Treasurer.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (January 2015). "The Chinese Century". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (June 29, 2015). "Joseph Stiglitz: how I would vote in the Greek referendum". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group.

- Joseph E. Stiglitz, "Measuring What Matters: Obsession with one financial figure, GDP, has worsened people's health, happiness and the environment, and economists want to replace it", Scientific American, vol. 323, no. 2 (August 2020), pp. 24–31.

Video and online sources

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2007). Committee hearing (via YouTube) (Speech). World Bank & Global Poverty, House Financial Services Committee (C-SPAN). Washington, D.C. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (presenter); Sarasin, Jacques (director) (May 2007). "1–5". Where is the world going, Mr. Stiglitz?. New York: First Run Features. Five-part series on two DVD discs.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (presenter); Sarasin, Jacques (director) (March 2009). Around the world with Joseph Stiglitz. Arte France / Les Productions Faire Bleu / Swan productions. Original French title Le monde selon Stiglitz.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Bilmes, Linda (February 28, 2008). The three trillion dollar war. Panel discussion regarding their new book. Columbia University.

- Book details: Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Bilmes, Linda (2008). The three trillion dollar war: the true cost of the Iraq conflict. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 9780393067019.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (February 9, 2010). "Bloomberg News" (Video) (YouTube). Interviewed by Andrea Catherwood. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

Stiglitz says EU should defend Greece from speculators

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (guest); Hendry, Hugh (guest); Casajuana, Carlos (guest) (February 9, 2010). "Newsnight" (Video) (BBC). Interviewed by Emily Maitlis. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

What should Europe do about Greece?

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (February 9, 2010). "Bloomberg News" (Video) (YouTube). Interviewed by Andrea Catherwood. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

Stiglitz says EU should defend Greece from speculators

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (August 21, 2014). Inequality, wealth, and growth: why capitalism is failing (Speech). 5th Lindau Meeting on Economic Sciences. Lake Constance, Germany: Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings. Retrieved October 29, 2014.

References

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (1966). Studies in the Theory of Economic Growth and Income Distribution (PDF) (Ph.D.). MIT. p. 4. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- "Joseph E. Stiglitz – Biographical." NobelPrize.org, https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economic-sciences/laureates/2001/stiglitz-bio.html, Accessed 24 September 2017.

- "Joseph Stiglitz, Clark Medalist 1979." American Economic Association, https://www.aeaweb.org/about-aea/honors-awards/bates-clark/joseph-stiglitz, 24 September 2017.

- "Former Chief Economists". worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 2017-11-04. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- "Former Members of the Council". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-10-23.

- Gochenour, Zachary, and Bryan Caplan. "An entrepreneurial critique of Georgism." The Review of Austrian Economics 26.4 (2013): 483–491.

- Orszag, Peter (March 3, 2015). "To Fight Inequality, Tax Land". Bloomberg View. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- Lucas, Edward. "Land-value tax: Why Henry George had a point". The Economist. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- "The Commission of Experts of the President of the UN General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System". un.org. United Nations.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Sen, Amartya; Fitoussi, Jean-Paul (2010-05-18). Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn't Add Up. The New Press. ISBN 9781595585196.

- "The International Economics Association". International Economics Association. October 14, 2013.

- "IEA World Congress 2014". International Economics Association. October 14, 2013. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013.

- Brown, Gordon (April 21, 2011). "The 2011 TIME 100". time.com.

- Taylor, Ihsan. "Best Sellers – The New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- https://rsf.org/en/joseph-e-stiglitz

- School, Columbia Business (2007-12-17). "Interview with Professor Joseph Stiglitz". The Tamer Center for Social Enterprise. Retrieved 2020-06-02.

- "International Who's who of Authors and Writers". 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Stiglitz, Joseph E. 1943– (Joseph Eugene Stiglitz)". encyclopedia.com. Cengage Learning.

- "Eight to receive honorary degrees". Harvard Gazette. 2014-05-29. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Aoki, Masahiko (2018). Transboundary Game of Life: Memoir of Masahiko Aoki. Springer. p. 59. ISBN 978-9811327575.

- Bowmaker, Simon W. (2019-09-20). When the President Calls: Conversations with Economic Policymakers. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-35552-0.

- "A shilling in the meter and a penny for your thoughts ... An Interview with Professor Joseph E Stiglitz" (PDF). Optima. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- Stiglitz, Joseph. CV (PDF). Columbia University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-13.

- Uchitelle, Louis (2001-07-21). "Columbia University Hires Star Economist". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- "Staff: Professor Joseph E Stiglitz". manchester.ac.uk. University of Manchester. Archived from the original on 12 January 2007.

- "Master Economics and Public Policy". sciences-po.fr. Edudier à Sciences Po. Archived from the original on 2009-10-15.

- Bruce C. Greenwald & Joseph E. Stiglitz: Keynesian, New Keynesian and New Classical Economics. Oxford Economics Papers, 39, March 1987, pp. 119–33. (PDF; 1,62 MB) Archived 2011-05-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Bruce C. Greenwald & Joseph E. Stiglitz: Examining Alternative Macroeconomic Theories. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, No. 1, 1988, pp. 201–70. (PDF; 5.50 MB) Archived 2011-05-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Smith, Noah (13 January 2017). "Tribal warfare in economics a thing of the past". The Australian Financial Review. Fairfax Media. Bloomberg.

Look on the Wikipedia pages of economists Joseph Stiglitz and Greg Mankiw or any of a number of prominent economists. On the sidebar on the right, you'll see an entry for "school or tradition". Both Stiglitz and Mankiw are listed as "New Keynesian". That makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. Stiglitz and Mankiw's research is in totally different areas. Stiglitz did work on asymmetric information, efficiency wages, land taxes and a host of other microeconomic phenomena ... Nor are their policy positions even remotely similar – Stiglitz is a hero to the left, while Mankiw is a small-government conservative. In fact, Mankiw did important research on some models called "New Keynesian". Stiglitz did not.

- "Joe Stiglitz and the IMF have warmed to each other". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- Greg Palast (October 10, 2001). "multi-day interview with Greg Palast". Gregpalast.com. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Greenwald, Bruce C. (2014-06-03). Creating a Learning Society: A New Approach to Growth, Development, and Social Progress. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15214-3.

- "Stiglitz Says Ties to Wall Street Doom Bank Rescue". Bloomberg News. April 17, 2009. Retrieved April 18, 2009.

- "Commission of Experts of the President of the UN General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System". un.org. United Nations.

- "Joseph Stiglitz apoya el movimiento 15-M". Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- "International Economic Association (IEA)". Iea-world.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Stiglitz, Joseph E. (6 November 2018). "Can American Democracy Come Back? | by Joseph E. Stiglitz". Project Syndicate. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- Richard J. Arnott & Joseph E. Stiglitz, 1979. "Aggregate Land Rents, Expenditure on Public Goods, and Optimal City Size," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Oxford University Press, vol. 93(4), pages 471–500.

- Stiglitz, J.E. (1977) The theory of local public goods. In: Feldstein, M.S. and R.P. Inman (eds.) The Economics of Public Services. MacMillan, London, pp. 274–333.

- Stiglitz, Joseph; Weiss, Andrew (February 1987). "Macro-Economic Equilibrium and Credit Rationing". Cambridge, MA. doi:10.3386/w2164. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rothschild, Michael; Stiglitz, Joseph (1976), "Equilibrium in Competitive Insurance Markets: An Essay on the Economics of Imperfect Information", Foundations of Insurance Economics, Springer Netherlands, pp. 355–375, doi:10.1007/978-94-015-7957-5_18, ISBN 9789048157891

- "On the impossibility of informationally efficient markets" (PDF).

- Dixit, Avinash K.; Stiglitz, Joseph E. (2001), "Monopolistic competition and optimum product diversity (May 1974)", The Monopolistic Competition Revolution in Retrospect, Cambridge University Press, pp. 70–88, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511492273.004, ISBN 9780511492273

- Krugman, Paul. "Increasing returns, monopolistic competition and global trade" (PDF).

- Stiglitz, Joseph E.; Shapiro, Carl (June 1984). "Equilibrium unemployment as a worker discipline device". The American Economic Review. American Economic Association via JSTOR. 74 (3): 433–44. JSTOR 1804018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Lecture 4" (PDF). coin.wne.uw.edu.pl. May 22, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- "Efficiency wages, the Shapiro-Stiglitz Model" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 15, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- "Consensus, dissensus, confusion: the 'Stiglitz Debate' in perspective". Archived from the original on 2007-04-22. Retrieved 2007-08-03.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Friedman, Benjamin M. (August 15, 2002). "Globalization: Stiglitz's Case". Nybooks.com. The New York Review of Books, Volume 49, Number 13. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Boettke, Peter J. "What Went Wrong with Economics?, Critical Review Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 35, 58" (PDF). Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- "Privatization, Information and Incentives" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2006-05-18. Retrieved 2007-05-15.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Whither Socialism?". Archived from the original on 1997-06-07. Retrieved 2007-09-26.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Brief Biography of Joseph E. Stiglitz". columbia.edu. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2011-08-29.

- Wade, Robert (January–February 2001). "Showdown at the World Bank". New Left Review. New Left Review. II (7): 124–37.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hage, Dave (October 11, 2000). "Joseph Stiglitz: A Dangerous Man, A World Bank Insider Who Defected". Star Tribune. Minneapolis: Commondreams.org. Archived from the original on August 14, 2013. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Hirsh, Michael (18 July 2009). "Why Washington ignores an economic prophet". Newsweek. Newsweek LLC.

- Mallaby, The World's Banker, p. 266.

- Stevenson, Richard W. (November 25, 1999). "Outspoken chief economist leaving World Bank". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Wade, Robert. US hegemony and the World Bank: Stiglitz's firing and Kanbur's resignation (PDF). UC Berkeley. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008.

- "Stiglitz documentation". Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. September 14, 2009. Archived from the original on 20 July 2015.

- "Terms of Reference Commission of Experts of the President of the United Nations General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System". Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- The Commission of Experts of the President of the UN General Assembly on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System, UN General Assembly

- NGLS. "Commission of Experts on Reforms of the International Monetary and Financial System, official site". Un-ngls.org. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Moore, Malcolm (Jan 17, 2012). "Stiglitz says European austerity plans are a 'suicide pact'". Telegraph. London. Retrieved April 26, 2012.