Sustainable forest management

Sustainable forest management (SFM) is the management of forests according to the principles of sustainable development. Sustainable forest management has to keep the balance between three main pillars: ecological, economic and socio-cultural. Successfully achieving sustainable forest management will provide integrated benefits to all, ranging from safeguarding local livelihoods to protecting the biodiversity and ecosystems provided by forests, reducing rural poverty and mitigating some of the effects of climate change.[1]

The "Forest Principles" adopted at the Earth Summit (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 captured the general international understanding of sustainable forest management at that time. A number of sets of criteria and indicators have since been developed to evaluate the achievement of SFM at the global, regional, country and management unit level. These were all attempts to codify and provide for independent assessment of the degree to which the broader objectives of sustainable forest management are being achieved in practice. In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Non-Legally Binding Instrument on All Types of Forests. The instrument was the first of its kind, and reflected the strong international commitment to promote implementation of sustainable forest management through a new approach that brings all stakeholders together.[2]

Definition

A definition of SFM was developed by the Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe (FOREST EUROPE), and has since been adopted by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).[3] It defines sustainable forest management as:

The stewardship and use of forests and forest lands in a way, and at a rate, that maintains their biodiversity, productivity, regeneration capacity, vitality and their potential to fulfill, now and in the future, relevant ecological, economic and social functions, at local, national, and global levels, and that does not cause damage to other ecosystems.

In simpler terms, the concept can be described as the attainment of balance – balance between society's increasing demands for forest products and benefits, and the preservation of forest health and diversity. This balance is critical to the survival of forests, and to the prosperity of forest-dependent communities.

For forest managers, sustainably managing a particular forest tract means determining, in a tangible way, how to use it today to ensure similar benefits, health and productivity in the future. Forest managers must assess and integrate a wide array of sometimes conflicting factors – commercial and non-commercial values, environmental considerations, community needs,[4] even global impact – to produce sound forest plans. In most cases, forest managers develop their forest plans in consultation with citizens, businesses, organizations and other interested parties in and around the forest tract being managed. The tools and visualization have been recently evolving for better management practices.[5]

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, at the request of Member States, developed and launched the Sustainable Forest Management Toolbox in 2014, an online collection of tools, best practices and examples of their application to support countries implementing sustainable forest management.[6]

Because forests and societies are in constant flux, the desired outcome of sustainable forest management is not a fixed one. What constitutes a sustainably managed forest will change over time as values held by the public change.[7]

Criteria and indicators

Criteria and indicators are tools which can be used to conceptualise, evaluate and implement sustainable forest management.[8] Criteria define and characterize the essential elements, as well as a set of conditions or processes, by which sustainable forest management may be assessed. Periodically measured indicators reveal the direction of change with respect to each criterion.

Criteria and indicators of sustainable forest management are widely used and many countries produce national reports that assess their progress toward sustainable forest management. There are nine international and regional criteria and indicators initiatives, which collectively involve more than 150 countries.[9] Three of the more advanced initiatives are those of the Working Group on Criteria and Indicators for the Conservation and Sustainable Management of Temperate and Boreal Forests (also called the Montréal Process),[10] Forest Europe,[11] and the International Tropical Timber Organization.[12] Countries who are members of the same initiative usually agree to produce reports at the same time and using the same indicators. Within countries, at the management unit level, efforts have also been directed at developing local level criteria and indicators of sustainable forest management. The Center for International Forestry Research, the International Model Forest Network[13] and researchers at the University of British Columbia have developed a number of tools and techniques to help forest-dependent communities develop their own local level criteria and indicators.[14][15][16] Criteria and Indicators also form the basis of third-party forest certification programs such as the Canadian Standards Association's[17] Sustainable Forest Management Standards and the Sustainable Forestry Initiative Standard.[18]

There appears to be growing international consensus on the key elements of sustainable forest management. Seven common thematic areas of sustainable forest management have emerged based on the criteria of the nine ongoing regional and international criteria and indicators initiatives. The seven thematic areas are:

- Extent of forest resources

- Biological diversity

- Forest health and vitality

- Productive functions of forest resources

- Protective functions of forest resources

- Socio-economic functions

- Legal, policy and institutional framework.

This consensus on common thematic areas (or criteria) effectively provides a common, implicit definition of sustainable forest management. The seven thematic areas were acknowledged by the international forest community at the fourth session of the United Nations Forum on Forests and the 16th session of the Committee on Forestry.[19][20] These thematic areas have since been enshrined in the Non-Legally Binding Instrument on All Types of Forests as a reference framework for sustainable forest management to help achieve the purpose of the instrument.

On January 5, 2012, the Montréal Process, Forest Europe, the International Tropical Timber Organization, and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, acknowledging the seven thematic areas, endorsed a joint statement of collaboration to improve global forest-related data collection and reporting and avoiding the proliferation of monitoring requirements and associated reporting burdens.

Ecosystem approach

The Ecosystem Approach has been prominent on the agenda of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) since 1995 . The CBD definition of the Ecosystem Approach and a set of principles for its application were developed at an expert meeting in Malawi in 1995, known as the Malawi Principles.[21] The definition, 12 principles and 5 points of "operational guidance" were adopted by the fifth Conference of Parties (COP5) in 2000. The CBD definition is as follows

The ecosystem approach is a strategy for the integrated management of land, water and living resources that promotes conservation and sustainable use in an equitable way. Application of the ecosystem approach will help to reach a balance of the three objectives of the Convention. An ecosystem approach is based on the application of appropriate scientific methodologies focused on levels of biological organization, which encompasses the essential structures, processes, functions and interactions among organisms and their environment. It recognizes that humans, with their cultural diversity, are an integral component of many ecosystems.

Sustainable forest management was recognized by parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in 2004 (Decision VII/11 of COP7) to be a concrete means of applying the Ecosystem Approach to forest ecosystems. The two concepts, sustainable forest management and the ecosystem approach, aim at promoting conservation and management practices which are environmentally, socially and economically sustainable, and which generate and maintain benefits for both present and future generations. In Europe, the MCPFE and the Council for the Pan-European Biological and Landscape Diversity Strategy (PEBLDS) jointly recognized sustainable forest management to be consistent with the Ecosystem Approach in 2006.[22][23][24][25]

Independent certification

Growing environmental awareness and consumer demand for more socially responsible businesses helped third-party forest certification emerge in the 1990s as a credible tool for communicating the environmental and social performance of forest operations.

There are many potential users of certification, including: forest managers, scientists, policy makers, investors, environmental advocates, business consumers of wood and paper, and individuals.

With third-party forest certification, an independent organization develops standards of good forest management, and independent auditors issue certificates to forest operations that comply with those standards. Forest certification verifies that forests are well-managed – as defined by a particular standard – and chain-of-custody certification tracks wood and paper products from the certified forest through processing to the point of sale.

This rise of certification led to the emergence of several different systems throughout the world. As a result, there is no single accepted forest management standard worldwide, and each system takes a somewhat different approach in defining standards for sustainable forest management.

In its 2009–2010 Forest Products Annual Market Review United Nations Economic Commission for Europe/Food and Agriculture Organization stated: "Over the years, many of the issues that previously divided the (certification) systems have become much less distinct. The largest certification systems now generally have the same structural programmatic requirements."[26]

Third-party forest certification is an important tool for those seeking to ensure that the paper and wood products they purchase and use come from forests that are well-managed and legally harvested. Incorporating third-party certification into forest product procurement practices can be a centerpiece for comprehensive wood and paper policies that include factors such as the protection of sensitive forest values, thoughtful material selection and efficient use of products.[27]

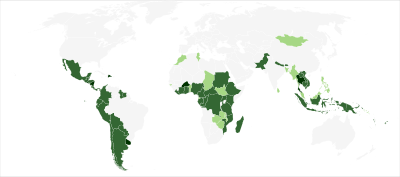

There are more than fifty certification standards worldwide, addressing the diversity of forest types and tenures. Globally, the two largest umbrella certification programs are:

The area of forest certified worldwide is growing slowly. PEFC is the world's largest forest certification system, with more than two-thirds of the total global certified area certified to its Sustainability Benchmarks.[28][29]

In North America, there are three certification standards endorsed by PEFC – the Sustainable Forestry Initiative,[30] the Canadian Standards Association's Sustainable Forest Management Standard,[31] and the American Tree Farm System.[32] FSC has five standards in North America – one in the United States[33] and four in Canada.[34]

While certification is intended as a tool to enhance forest management practices throughout the world, to date most certified forestry operations are located in Europe and North America. A significant barrier for many forest managers in developing countries is that they lack the capacity to undergo a certification audit and maintain operations to a certification standard.[35]

Forest governance

Although a majority of forests continue to be owned formally by government, the effectiveness of forest governance is increasingly independent of formal ownership.[36] Since neo-liberal ideology in the 1980s and the emanation of the climate change challenges, evidence that the state is failing to effectively manage environmental resources has emerged.[37] Under neo-liberal regimes in the developing countries, the role of the state has diminished and the market forces have increasingly taken over the dominant socio-economic role.[38] Though the critiques of neo-liberal policies have maintained that market forces are not only inappropriate for sustaining the environment, but are in fact a major cause of environmental destruction.[39] Hardin's tragedy of the commons (1968) has shown that the people cannot be left to do as they wish with land or environmental resources. Thus, decentralization of management offers an alternative solution to forest governance.[36]

The shifting of natural resource management responsibilities from central to state and local governments, where this is occurring, is usually a part of broader decentralization process.[40] According to Rondinelli and Cheema (1983), there are four distinct decentralization options: these are: (i) Privatization – the transfer of authority from the central government to non-governmental sectors otherwise known as market-based service provision, (ii) Delegation – centrally nominated local authority, (iii) Devolution – transfer of power to locally acceptable authority and (iv) Deconcentration – the redistribution of authority from the central government to field delegations of the central government. The major key to effective decentralization is increased broad-based participation in local-public decision making. In 2000, the World Bank report reveals that local government knows the needs and desires of their constituents better than the national government, while at the same time, it is easier to hold local leaders accountable. From the study of West African tropical forest, it is argued that the downwardly accountable and/or representative authorities with meaningful discretional powers are the basic institutional element of decentralization that should lead to efficiency, development and equity.[41] This collaborates with the World Bank report in 2000 which says that decentralization should improve resource allocation, efficiency, accountability and equity "by linking the cost and benefit of local services more closely".[42]

Many reasons point to the advocacy of decentralization of forest. (i) Integrated rural development projects often fail because they are top-down projects that did not take local people's needs and desires into account.[43] (ii) National government sometimes have legal authority over vast forest areas that they cannot control,[44] thus, many protected area projects result in increased biodiversity loss and greater social conflict.[45] Within the sphere of forest management, as state earlier, the most effective option of decentralization is "devolution"-the transfer of power to locally accountable authority.[46] However, apprehension about local governments is not unfounded. They are often short of resources, may be staffed by people with low education and are sometimes captured by local elites who promote clientelist relation rather than democratic participation.[47] Enters and Anderson (1999) point that the result of community-based projects intended to reverse the problems of past central approaches to conservation and development have also been discouraging.

Broadly speaking, the goal of forest conservation has historically not been met when, in contrast with land use changes; driven by demand for food, fuel and profit.[48] It is necessary to recognize and advocate for better forest governance more strongly given the importance of forest in meeting basic human needs in the future and maintaining ecosystem and biodiversity as well as addressing climate change mitigation and adaptation goal.[36] Such advocacy must be coupled with financial incentives for government of developing countries and greater governance role for local government, civil society, private sector and NGOs on behalf of the "communities".[49]

National Forest Funds

The development of National Forest Funds is one way to address the issue of financing sustainable forest management.[50] National forest funds (NFFs) are dedicated financing mechanisms managed by public institutions designed to support the conservation and sustainable use of forest resources.[51] As of 2014, there are 70 NFFs operating globally.[52]

Forest genetic resources

Appropriate use and long-term conservation of forest genetic resources (FGR) is a part of sustainable forest management.[53] In particular when it comes to the adaptation of forests and forest management to climate change.[54] Genetic diversity ensures that forest trees can survive, adapt and evolve under changing environmental conditions. Genetic diversity in forests also contributes to tree vitality and to the resilience towards pests and diseases. Furthermore, FGR has a crucial role in maintaining forest biological diversity at both species and ecosystem levels.[55]

Selecting carefully the forest reproductive material with emphasis on getting a high genetic diversity rather than aiming at producing a uniform stand of trees, is essential for sustainable use of FGR. Considering the provenance is crucial as well. For example in relation to climate change, local material may not have the genetic diversity or phenotypic plasticity to guarantee good performance under changed conditions. A different population from further away, which may have experienced selection under conditions more like those forecast for the site to be reforested, might represent a more suitable seed source.[56]

Regional action

In the Developing world

In December of 2007, at the Climate Change Conference in Bali, the issue of deforestation in the developing world in particular was raised and discussed. The foundations of a new incentive mechanism for encouraging sustainable forest management measures was therefore laid in hopes of reducing world deforestation rates. This mechanism was formalized and adopted as REDD in November of 2010 at the Climate Change Conference in Cancun by UNFCCC COP 16. Developing country who are signatories of the CBD were encouraged to take measure to implement REDD activities in the hope of becoming more active contributors of global efforts aimed at the mitigation greenhouse gas. After all, deforestation and forest degradation account for roughly 15% of total global greenhouse gas emissions.[57] The REDD activities are formally tasked with “reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation; and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries”. REDD+ works in 3 phases. The first phase consists of developing viable strategies, while the second phase begins work on technology development and technology transfer to the developing countries taking part in REDD+ activities. The last phase measures and reports the implementation of the action taken [58]

Canada

The province of Ontario has its own sustainable forest management measures in place. A little less than half of all the publicly owned forest of Ontario are managed forest whose management activities are required by The Crown Forest Sustainability Act to be managed sustainably. Sustainable management is often done by forest companies who are granted Sustainable Forest Licenses which are valid for 20 years. The main goals of the Ontario’s sustainable forest management efforts is to ensure that the forest are kept healthy and productive, conserving biodiversity, all whilst supporting communities and forest industry jobs. All management strategies and plans are highly regulated, arranged to last for a 10-year period, and follow the strict guidelines of the Forest Management Planning Manual. Alongside public sustainable forest management, the government of Ontario encourages sustainable forest management of Ontario’s private forests as well through incentives [59]

Russia

In 2019 after severe wildfires and public pressure the Russian government decided to take a number of measures for more effective forest management, what is considered as a big victory for the Environmental movement[60]

Indonesia

In August 2019, a court in Indonesia stopped the construction of a dam that could heavily hurt forests and villagers in the area[61]

United States of America

In the beginning of the year 2020 the "Save the Redwoods League" after a successful crowdfunding campaign bought " Alder Creek" a piece of land 583 acres large, with 483 big Sequoia trees including the 5th largest tree in the world. The organizations plan to make there forest thinning[62] that is a controversial operation[63]

See also

- Biodiversity

- Conservation biology

- Ecosystem management

- Ecosystem-based management

- Environmental protection

- Forest conservation in the United States

- Green furniture

- Habitat conservation

- Healthy Forests Initiative

- Natural environment

- Natural landscape

- Nature

- Overexploitation

- Renewable resource

- Sustainability

- Sustainable development

- Sustainable land management

- Category:Forest conservation

References

- "LEDS GP Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use Working Group factsheet" (PDF). Low Emission Development Strategies Global Partnership (LEDS GP). Retrieved 23 March 2016.

- Antony, J R., Lal, S.B. (2013). Forestry Principles And Applications. p. 166.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Ministerial Conference on the Protection of Forests in Europe". Mcpfe.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Evans, K., De Jong, W., and Cronkleton, P. (2008) "Future Scenarios as a Tool for Collaboration in Forest Communities". ''S.A.P.I.EN.S.'' '''1''' (2)". Sapiens.revues.org. 1 October 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Mozgeris, G. (2008) "The continuous field view of representing forest geographically: from cartographic representation towards improved management planning". ''S.A.P.I.EN.S.'' '''1''' (2)". Sapiens.revues.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Sustainable Forest Management Toolbox" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

- Rametsteiner, Ewald; Simula, Markku (2003). "Forest certification—an instrument to promote sustainable forest management?". Journal of Environmental Management. 67 (1): 87. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Guidelines for Developing, Testing and Selecting Criteria and Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management Ravi Prabhu, Carol J. P. Colfer and Richard G. Dudley. 1999. CIFOR. The Criteria & Indicators Toolbox Series.

- Criteria and Indicators for Sustainable Forest Management: A Compendium. Paper compiled by Froylán Castañeda, Christel Palmberg-Lerche and Petteri Vuorinen, May 2001. Forest Management Working Papers, Working Paper 5. Forest Resources Development Service, Forest Resources Division. FAO, Rome (unpublished).

- Montréal Process Indicators

- MCPFE indicators Archived 14 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ITTO

- "International Model Forest Network". Imfn.net. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "CIFOR Criteria and Indicators Toolbox Series". Cifor.cgiar.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- International Model Forest Network Criteria and Indicators Archived 23 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- SFM Indicator Knowledge Base

- "Canadian Standards Association". Csa-international.org. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Sustainable Forestry Initiative Introduction Page 1" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- United Nations Forum on Forests (2004)

- Committee on Forestry (2003)

- Malawi Principles Archived 23 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "MCPFE". MCPFE. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Council". Strategyguide.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Pan-European Biological and Landscape Diversity Strategy". Strategyguide.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "PEBLD Strategy" (PDF). Strategyguide.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "2009–2010 Forest Products Annual Market Review Page 121" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Erin Malec (5 October 2011). "Forest Certification Resource Center". Metafore.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- UNECE/FAO Forest Products Annual Market Review

- "PEFC". PEFC. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Sustainable Forest Initiative". Sfiprogram.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Canadian Standards Association". Csa-international.org. Archived from the original on 19 October 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "American Tree Farm System". Treefarmsystem.org. 22 November 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Forest Stewardship Council (US)". Fscus.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- "Forest Stewardship Council (Canada)". Fsccanada.org. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- Auer, M. (2012). 'Group forest certification for smallholders in Vietnam: An early test and future prospects'. Human ecology 40(1): 5–14.

- Agrawal, A., Chhatre, A, and Hardin, R. (2008). 'Changing Governance of the World's Forest'. Science 320: 1460–1462

- Lutz, E, and Caldecott, J. (1996). Decentralization and biodiversity: a world bank symposium. Washington: The World Bank.

- Hague, M. (1999). 'The Fate of sustainable development under neo-liberal regime in developing countries', International political review 20(2): 197–218.

- Stokke (1999). 'Sustainable development: A multi-faceted challenge' European journal of development 3(1): 8–31.

- Margulis, S. . 'Decentralized environmental management', Annual World Bank Report.

- Ribott, (1990). 'Accountable representation and power in Participatory and decentralized environmental management', Unasylva 50(4).

- World Bank 1988

- Lutz, E and Caldcott (1999) Decentralisation and biodiversity conservation, A World bank symposium. Washington: The World Bank

- Enters and Anderson (1999) Rethinking the decentralisation and devolution of biodiversity conservation Unasylva 50(4)

- Enters and Anderson (1999)

- Rondinelli and Cheema (1981)Decentralization and development, sage publication, London

- M, Larson "Natural resource and degradation in Nicaragua: Are local governments up to the job?

- Larson (2002)

- Rondinelli and Chaeema (1999)

- 2012 STUDY ON FOREST FINANCING (PDF). Advisory Group on Finance Collaborative Partnership on Forests. June 2012.

- Matta, Rao (2015). Towards effective national forest funds, FAO Forestry Paper 174 (PDF). Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-108706-0.

- Matta, Rao (2015). Towards effective national forest funds, FAO Forestry Paper 174 (PDF). Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-108706-0.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2014). "The State of the World's Forest Genetic Resources" (PDF). Commission on genetic resources for food and agriculture.

- Koskela, J., Buck, A. and Teissier du Cros, E. (eds) (2007). "Climate change and forest genetic diversity: Implications for sustainable forest management in Europe" (PDF). European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN). Bioversity International, Rome, Italy.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- de Vries, S.M.G., Alan, M., Bozzano, M., Burianek, V., Collin, E., Cottrell, J., Ivankovic, M., Kelleher, C.T., Koskela, J., Rotach, P., Vietto, L. and Yrjänä, L (2015). "Pan-European strategy for genetic conservation of forest trees and establishment of a core network of dynamic conservation units" (PDF). European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN), Bioversity International. Rome, Italy.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Konnert, M., Fady, B., Gömöry, D., A'Hara, S., Wolter, F., Ducci, F., Koskela, J., Bozzano, M., Maaten, T. and Kowalczyk, J. (2015). "Use and transfer of forest reproductive material in Europe in the context of climate change" (PDF). European Forest Genetic Resources Programme (EUFORGEN), Bioversity International, Rome, Italy.: xvi and 75 p.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "What is REDD+?". The Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF). Forest Carbon Partnership Facility. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "REDD+ and Biodiversity Benefits". Convention on Biological Diversity. United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- "Sustainable forest management". Ontario.ca. Government of Ontario. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- Vasilieva, Tatiana. "Life in the Siberian haze". Greenpeace International. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Hanafiah, Junaidi (2 September 2019). "Indonesian court cancels dam project in last stronghold of tigers, rhinos". Mongabay. Retrieved 9 September 2019.

- Rosane, Olivia (10 January 2020). "World's Fifth-Largest Tree Now Safe From Loggers in an 'Inspiring Outpouring of Generosity'". Ecowatch. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Stop Thinning Forests". Stop Thinning Forests. Retrieved 12 January 2020.