Income and fertility

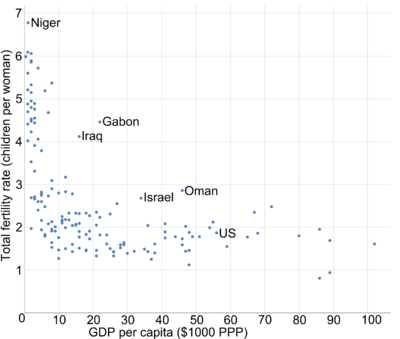

Income and fertility is the association between monetary gain on one hand, and the tendency to produce offspring on the other. There is generally an inverse correlation between income and the total fertility rate within and between nations. The higher the degree of education and GDP per capita of a human population, subpopulation or social stratum, the fewer children are born in any industrialized country.[3] In a 1974 UN population conference in Bucharest, Karan Singh, a former minister of population in India, illustrated this trend by stating "Development is the best contraceptive."[4]

Demographic-economic paradox

Herwig Birg has called the inverse relationship between income and fertility a “demo-economic paradox”. Evolutionary biology dictates that the more successful individuals, or in this case countries, would seek to develop optimum conditions for their life and reproduction. However, in the last half of the 20th Century it has become clear that the economic success of developed countries is being counterbalanced by a demographic failure (that is, a below replacement fertility rate) that may prove destructive for their future economies and societies.[5]

Individual level observances

In the years after the revolutions of 1989 in Russia, people who were more affected by labour market crises seemed to have a higher probability of having another child than those who were less affected.[6]

Causes and related factors

Coale's Three Preconditions for Decline in Fertility comes from the saying, “ready, willing and able”. Societal changes may induce fertility declines, but they will do so only if three preconditions are met: ready, willing and able. A person and the population must have a reason to want to limit fertility. If people have economic and social opportunities that make it advantageous to limit fertility they will be more willing to limit it. There must be economic and psychosocial costs involved such as the cost of birth control or abortions.[7]

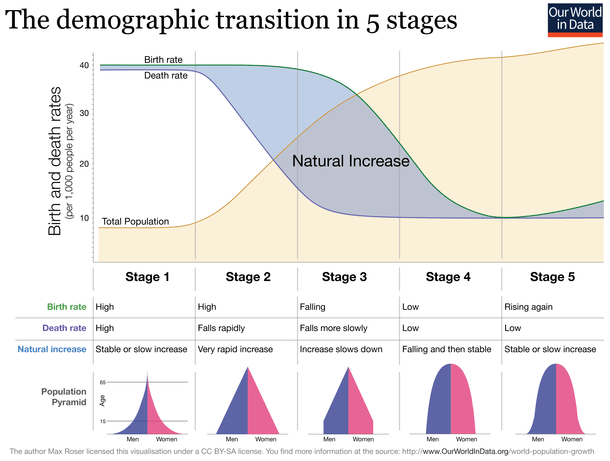

It is hypothesized that the observed trend in many countries of having fewer children has come about as a response to increased life expectancy, reduced childhood mortality, improved female literacy and independence, and urbanization that all result from increased GDP per capita,[8] consistent with the demographic transition model. The increase in GDP in Eastern Europe after 1990 has been correlated with childbearing postponement and a sharp decline in fertility.[9]

In advanced countries where birth control is the norm, increased income is likewise associated with decreased fertility. Theories behind this include:

- People earning more have a higher opportunity cost if they focus on childbirth and parenting rather than their continued career[9]

- Women who can economically sustain themselves have less incentive to become married.[9]

- Higher-income parents value quality over quantity and so spend their resources on fewer children.[9]

Religion sometimes modifies the effect; higher income is associated with slightly increased fertility among Catholic couples but associated with slightly decreased fertility among Protestant couples.[10]

Generally, a Developed country has a lower fertility rate while a less economically developed country has a higher fertility rate. For example, the total fertility rate for Japan, a more developed country, with per capita GDP of $32,600 in 2009, was 1.22 children born per woman. But total fertility rate in Ethiopia, with a per capita GDP of $900 in 2009, was 6.17 children born per woman.[11]

Consequences

Across countries, there is a strong negative correlation between Gross domestic product and fertility, and ultimately it is proven that a strong negative correlation exists between household income and fertility.

A reduction in fertility can lead to an aging population, which can lead to a variety of problems. See for example the Demographics of Japan.

A related concern is that high birth rates tend to place a greater burden of child rearing and education on populations already struggling with poverty. Consequently, inequality lowers average education and hampers economic growth.[12] Also, in countries with a high burden of this kind, a reduction in fertility can hamper economic growth as well as the other way around.[13] Richer countries have a lower fertility rate than poorer ones, and high income families have fewer kids than low-income ones.[14]

Contrary findings

A United Nations report in 2002 came to the conclusion that sharp declines in fertility rates in India, Nigeria, and Mexico occurred despite low levels of economic development.[15]

Every country could differ in their respective relationship between income and fertility. Some countries show that income and fertility are directly related but other countries show a directly inverse relationship.[16]

Increased unemployment is generally associated with lower fertility.[9] A study in France came to the result that employment instability has a strong and persistent negative effect on the final number of children for both men and women and contributes to fertility postponement for men. It also came to the result that employment instability has a negative influence on fertility among those with more egalitarian views about the division of labor but still a positive influence for women with more traditional views.[17]

Fertility declines have been seen during economic recessions. This phenomenon is seen as a result of pregnancy postponement, especially of first births. However, this effect can be short-term and largely compensated for during later times of economic prosperity.[9]

Two recent studies in the United States show, that in some circumstances, families whose income has increased will have more children.[18]

Fertility J-curve

Some scholars have recently questioned the assumption that economic development and fertility are correlated in a simple negative manner. A study published in Nature in 2009 found that when using the Human Development Index instead of the GDP as measure for economic development, fertility follows a J-shaped curve: with rising economic development, fertility rates indeed do drop at first but then begin to rise again as the level of social and economic development increases while still remaining below the replacement rate.[19][20]

In an article published in Nature, Myrskylä et al. pointed out that “unprecedented increases” in social and economic development in the 20th century had been accompanied by considerable declines in population growth rates and fertility. This negative association between human fertility and socio-economic development has been “one of the most solidly established and generally accepted empirical regularities in the social sciences”.[20] The researchers used cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses to examine the relationship between total fertility rate (TFR) and the human development index (HDI).

The main finding of the study was that, in highly developed countries with an HDI above 0.9, further development halts the declining fertility rates. This means that the previously negative development-fertility association is reversed; the graph becomes J-shaped. Myrskylä et al. contend that there has occurred “a fundamental change in the well-established negative relationship between fertility and development as the global population entered the twenty-first century”.[20]

Some researchers doubt J-shaped relationship fertility and socio-economic development (Luci and Thevenon, 2010;[21] Furuoka, 2009). For example, Fumitaka Furuoka (2009) employed a piecewise regression analysis to examine the relationship between total fertility rate and human development index. However, he found no empirical evidence to support the proposition that advances in development are able to reverse declining fertility rates.

More precisely, the empirical findings of Furuoka’s 2009 study indicate that in countries with a low human development index, higher levels of HDI tend to be associated with lower fertility rates. Likewise, in countries with a high human development index, higher levels of HDI are associated with lower fertility rates, although the relationship is weaker. Furuoka's findings support the "conventional wisdom" that higher development is consistently correlated with lower overall fertility.[22]

See also

References

- "Field Listing: Total Fertility Rate". The World Factbook. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- "Country Comparison: GDP - Per Capita (PPP)". The World Factbook. Retrieved 2016-04-24.

- Vandenbroucke, Guillaume (December 13, 2016). "The Link between Fertility and Income". Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis (USA).

- Weil, David N. (2004). Economic Growth. Addison-Wesley. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-201-68026-3.

- Birg, Herwig (October 18, 2000). "Demographic Ageing and Population Decline in 21st Century Germany - Consequences for the Systems of Social Insurance" (PDF). United Nations Dept of Social and Economic Affairs.

- Kohler H.P.; Kohler, I. (2002). "Fertility Decline in Russia in the Early and Mid 1990s: The Role of Economic Uncertainty and Labour Market Crises" (PDF). European Journal of Population. 18 (3): 233–262. doi:10.1023/A:1019701812709.

- van de Kaa, Dirk J. (2004). "["Ready, Willing, and Able": Ansley J. Coale, 1917-2002]". The Journal of Interdisciplinary History. 34 (3): 509–511. JSTOR 3657089.

- Montgomery, Keith, The demographic transition, University of Wisconsin-Marathon County, archived from the original on 18 October 2012

- Balbo, Nicoletta; Billari, Francesco C.; Mills, Melinda (2012). "Fertility in Advanced Societies: A Review of Research". European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie. 29 (1): 1–38. doi:10.1007/s10680-012-9277-y. PMC 3576563. PMID 23440941.

- Charles F. Westoff; R. G. Potter (2015). Third Child: A Study in the Prediction of Fertility. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400876426. Page 238

- "Ethiopia" (PDF). A Country Status Report on Health and Poverty (In Two Volumes) the World Bank Group Africa Region Human Development & Ministry of Health, Ethiopia. II: Main Report. July 2005.

- de la Croix, David; Doepcke, Matthias (2003). "Inequality and growth: why differential fertility matters" (PDF). American Economic Review. 4: 1091–1113.

- UNFPA: Population and poverty. Achieving equity, equality and sustainability. Population and development series no. 8, 2003.

- Stanford, Joseph B.; Smith, KEN R. (2013). "Marital Fertility and Income: Moderating Effects of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints Religion in Utah". Journal of Biosocial Science. 45 (2): 239–48. doi:10.1017/S002193201200065X. PMID 23069479.

- Maria E. Cosio-Zavala (2002). "Examining Changes in the Status of Women And Gender as Predictors Of Fertility Change Issues in Intermediate-Fertility Countries

Part of: Completing the Fertility Transition" (PDF). United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. - Hutzler, S.; Sommer, C.; Richmond, P. (2016). "On the relationship between income, fertility rates and the state of democracy in society" (PDF). Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications. 452: 9–18. Bibcode:2016PhyA..452....9H. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2016.02.011.

- Daniel Ciganda (2015). "Unstable work histories and fertility in France: An adaptation of sequence complexity measures to employment trajectories". Demographic Research.

- "How Income Affects Fertility". Institute for Family Studies. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- "The best of all possible worlds? A link between wealth and breeding". The Economist. August 6, 2009.

- Myrskylä, Mikko; Kohler, Hans-Peter; Billari, Francesco C. (2009). "Advances in development reverse fertility declines". Nature. 460 (7256): 741–3. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..741M. doi:10.1038/nature08230. PMID 19661915.

- Luci, A; Thvenon, O (2010). "Does economic development drive the fertility rebound in OECD countries?". Paper Presented in the European Population Conference 2010 (EPC2010), Vienna, Austria, September 1–4, 2010.

- Fumitaka Furuoka (2009). "Looking for a J-shaped development-fertility relationship: Do advances in development really reverse fertility declines?". Economics Bulletin. 29: 3067–3074.

External links

- Macleod, Mairi (29 October 2013), Population paradox: Why richer people have fewer kids, New Scientist