Convention on Biological Diversity

The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), known informally as the Biodiversity Convention, is a multilateral treaty. The Convention has three main goals including: the conservation of biological diversity (or biodiversity); the sustainable use of its components; and the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from genetic resources.

| |

| Type | Multilateral environmental agreement |

|---|---|

| Context | Environmentalism, Biodiversity conservation |

| Drafted | 22 May 1992 |

| Signed | 5 June 1992 – 4 June 1993 |

| Location | Rio de Janeiro, Brazil New York, United States |

| Effective | 29 December 1993 |

| Condition | Ratification by 30 States |

| Parties | 196 States

|

| Depositary | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

| Languages | |

In other words, its objective is to develop national strategies for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity. It is often seen as the key document regarding sustainable development. The Convention was opened for signature at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro on 5 June 1992 and entered into force on 29 December 1993. CBD has two supplementary agreements - Cartagena Protocol and Nagoya Protocol.

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity is an international treaty governing the movements of living modified organisms (LMOs) resulting from modern biotechnology from one country to another. It was adopted on 29 January 2000 as a supplementary agreement to the Convention on Biological Diversity and entered into force on 11 September 2003.[1]

The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization (ABS) to the Convention on Biological Diversity is a supplementary agreement to the Convention on Biological Diversity. It provides a transparent legal framework for the effective implementation of one of the three objectives of the CBD: the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources. The Nagoya Protocol on ABS was adopted on 29 October 2010 in Nagoya, Japan and entered into force on 12 October 2014, 90 days after the deposit of the fiftieth instrument of ratification. Its objective is the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources, thereby contributing to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.[2]

Origin and scope

The notion of an international convention on bio-diversity was conceived at a United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Ad Hoc Working Group of Experts on Biological Diversity in November 1988. The subsequent year, the Ad Hoc Working Group of Technical and Legal Experts was established for the drafting of a legal text which addressed the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, as well as the sharing of benefits arising from their utilization with sovereign states and local communities. In 1991, an intergovernmental negotiating committee was established, tasked with finalizing the convention's text.[3]

A Conference for the Adoption of the Agreed Text of the Convention on Biological Diversity was held in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1992, and its conclusions were distilled in the Nairobi Final Act.[4] The Convention's text was opened for signature on 5 June 1992 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (the Rio "Earth Summit"). By its closing date, 4 June 1993, the convention had received 168 signatures. It entered into force on 29 December 1993.[3]

The convention recognized for the first time in international law that the conservation of biodiversity is "a common concern of humankind" and is an integral part of the development process. The agreement covers all ecosystems, species, and genetic resources. It links traditional conservation efforts to the economic goal of using biological resources sustainably. It sets principles for the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the use of genetic resources, notably those destined for commercial use.[5] It also covers the rapidly expanding field of biotechnology through its Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety, addressing technology development and transfer, benefit-sharing and biosafety issues. Importantly, the Convention is legally binding; countries that join it ('Parties') are obliged to implement its provisions.

The convention reminds decision-makers that natural resources are not infinite and sets out a philosophy of sustainable use. While past conservation efforts were aimed at protecting particular species and habitats, the Convention recognizes that ecosystems, species and genes must be used for the benefit of humans. However, this should be done in a way and at a rate that does not lead to the long-term decline of biological diversity.

The convention also offers decision-makers guidance based on the precautionary principle which demands that where there is a threat of significant reduction or loss of biological diversity, lack of full scientific certainty should not be used as a reason for postponing measures to avoid or minimize such a threat. The Convention acknowledges that substantial investments are required to conserve biological diversity. It argues, however, that conservation will bring us significant environmental, economic and social benefits in return.

The Convention on Biological Diversity of 2010 banned some forms of geoengineering.

Issues

Some of the many issues dealt with under the convention include:[6]

- Measures the incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity.

- Regulated access to genetic resources and traditional knowledge, including Prior Informed Consent of the party providing resources.

- Sharing, in a fair and equitable way, the results of research and development and the benefits arising from the commercial and other utilization of genetic resources with the Contracting Party providing such resources (governments and/or local communities that provided the traditional knowledge or biodiversity resources utilized).

- Access to and transfer of technology, including biotechnology, to the governments and/or local communities that provided traditional knowledge and/or biodiversity resources.

- Technical and scientific cooperation.

- Coordination of a global directory of taxonomic expertise (Global Taxonomy Initiative).

- Impact assessment.

- Education and public awareness.

- Provision of financial resources.

- National reporting on efforts to implement treaty commitments.

Cartagena Protocol

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety of the Convention, also known as the Biosafety Protocol, was adopted in January 2000. The Biosafety Protocol seeks to protect biological diversity from the potential risks posed by living modified organisms resulting from modern biotechnology.[7]

The Biosafety Protocol makes clear that products from new technologies must be based on the precautionary principle and allow developing nations to balance public health against economic benefits. It will for example let countries ban imports of a genetically modified organism if they feel there is not enough scientific evidence the product is safe and requires exporters to label shipments containing genetically modified commodities such as corn or cotton.[7]

The required number of 50 instruments of ratification/accession/approval/acceptance by countries was reached in May 2003. In accordance with the provisions of its Article 37, the Protocol entered into force on 11 September 2003.[8]

Global Strategy for Plant Conservation

In April 2002, the parties of the UN CBD adopted the recommendations of the Gran Canaria Declaration Calling for a Global Plant Conservation Strategy, and adopted a 16-point plan aiming to slow the rate of plant extinctions around the world by 2010.

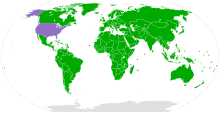

Parties

As of 2016, the Convention has 196 parties, which includes 195 states and the European Union.[9] All UN member states—with the exception of the United States—have ratified the treaty. Non-UN member states that have ratified are the Cook Islands, Niue, and the State of Palestine. The Holy See and the states with limited recognition are non-parties. The US has signed but not ratified the treaty,[10] and has not announced plans to ratify it.

The European Union created the Cartagena Protocol to enhance biosafety regulation and propagate the 'precautionary principle' over the 'sound science principle' defended by the United States. Whereas the impact of the Cartagena Protocol on domestic regulations has been substantial, its impact on international trade law remains uncertain. In 2006, The World Trade Organization (WTO) ruled that the European Union violated international trade law between 1999 and 2003 by imposing a moratorium on the approval of genetically modified organisms (GMO) imports. Disappointing the United States, the panel nevertheless ‘‘decided not to decide’’ by not invalidating the stringent European biosafety regulations.[11]

International bodies established

Conference of the Parties: The convention's governing body is the Conference of the Parties (COP), consisting of all governments (and regional economic integration organizations) that have ratified the treaty. This ultimate authority reviews progress under the Convention, identifies new priorities, and sets work plans for members. The COP can also make amendments to the Convention, create expert advisory bodies, review progress reports by member nations, and collaborate with other international organizations and agreements.

The Conference of the Parties (COP) uses expertise and support from several other bodies that are established by the Convention. In addition to committees or mechanisms established on an ad hoc basis, the main organs are:

Secretariat: The CBD Secretariat, based in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, operates under UNEP, the United Nations Environment Programme. Its main functions are to organize meetings, draft documents, assist member governments in the implementation of the programme of work, coordinate with other international organizations, and collect and disseminate information.

Subsidiary Body for Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice (SBSTTA): The SBSTTA is a committee composed of experts from member governments competent in relevant fields. It plays a key role in making recommendations to the COP on scientific and technical issues. The next two meetings of the SBSTTA will be 25–29 November 2019 in Montreal, Canada (SBSTTA-23), and 18–23 May 2020 in Montreal, Canada (SBSTTA-24). The current chair of the SBSTTA Bureau is Mr. Hesiquio Benitez Diaz of Mexico.

Subsidiary Body on Implementation (SBI): In 2014, the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity established the Subsidiary Body on Implementation (SBI) to replace the Ad Hoc Open-ended Working Group on Review of Implementation of the Convention. The four functions and core areas of work of SBI are: (a) review of progress in implementation; (b) strategic actions to enhance implementation; (c) strengthening means of implementation; and (d) operations of the convention and the Protocols. The first meeting of the SBI was held on 2–6 May 2016 and the second meeting was held on 9–13 July 2018, both in Montreal, Canada. The third meeting of the SBI will be held on 25–29 May 2020 in Montreal, Canada. The Bureau of the Conference of the Parties serves as the Bureau of the SBI. The current chair of the SBI is Ms. Charlotta Sörqvist of Sweden.

Country implementation

National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAP)

"National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs) are the principal instruments for implementing the Convention at the national level (Article 6). The Convention requires countries to prepare a national biodiversity strategy (or equivalent instrument) and to ensure that this strategy is mainstreamed into the planning and activities of all those sectors whose activities can have an impact (positive and negative) on biodiversity. To date [2012-02-01], 173 Parties have developed NBSAPs in line with Article 6."[12]

For example, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Tanzania have carried out elaborate responses to conserve individual species and specific habitats. The United States of America, a signatory who has not yet ratified the treaty,[13] has produced one of the most thorough implementation programs through species Recovery Programs and other mechanisms long in place in the US for species conservation.

Singapore has also established a detailed National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.[14] The National Biodiversity Centre of Singapore represents Singapore in the Convention for Biological Diversity.[15]

National Reports

In accordance with Article 26 of the Convention, Parties prepare national reports on the status of implementation of the Convention.

Executive secretary

The current acting executive secretary is Elizabeth Maruma Mrema, who took up this post on 1 December 2019.

The previous executive secretaries were:

Cristiana Pașca Palmer (2017-2019), Braulio Ferreira de Souza Dias (2012-2017), Ahmed Djoghlaf (2006-2012), Hamdallah Zedan (1998-2005), Calestous Juma (1995-1998), and Angela Cropper (1993-1995).

Nagoya Protocol

The Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity[16] is a supplementary agreement to the Convention on Biological Diversity. It provides a transparent legal framework for the effective implementation of one of the three objectives of the CBD: the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources. The Protocol was adopted on 29 October 2010 in Nagoya, Aichi Province, Japan, and entered into force on 12 October 2014. Its objective is the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources, thereby contributing to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity.[17]

Meetings of the parties

1994 COP 1

The first ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in November and December 1994, in Nassau, Bahamas.[18]

1995 COP 2

The second ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in November 1995, in Jakarta, Indonesia.[19]

1996 COP 3

The third ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in November 1996, in Buenos Aires, Argentina.[20]

1998 COP 4

The fourth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in May 1998, in Bratislava, Slovakia.[21]

1999 EXCOP 1

The First Extraordinary Meeting of the Conference of the Parties took place in February 1999, in Cartagena, Colombia.[22]

2000 COP 5

The fifth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in May 2000, in Nairobi, Kenya.[23]

2002 COP 6

The sixth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in April 2002, in The Hague, Netherlands.[24]

2004 COP 7

The seventh ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in February 2004, in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.[25]

2006 COP 8

The eighth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in March 2006, in Curitiba, Brazil.[26]

2008 COP 9

The ninth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in May 2008, in Bonn, Germany.[27]

2010 COP 10

The tenth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place in October 2010, in Nagoya, Japan.[28]

2012 COP 11

Leading up to the Conference of the Parties (COP 11) meeting on biodiversity in Hyderabad, India 2012, preparations for a World Wide Views on Biodiversity has begun, involving old and new partners and building on the experiences from the World Wide Views on Global Warming.[29]

2014 COP 12

Under the theme, "Biodiversity for Sustainable Development," thousands of representatives of governments, NGOs, indigenous peoples, scientists and the private sector gathered in Pyeongchang, Republic of Korea in October 2014 for the 12th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 12).[30]

From 6–17 October 2014, Parties discussed the implementation of the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 and its Aichi Biodiversity Targets, which are to be achieved by the end of this decade. The results of Global Biodiversity Outlook 4, the flagship assessment report of the CBD informed the discussions.

The conference gave a mid-term evaluation to the UN Decade on Biodiversity (2011-2020) initiative, which aims to promote the conservation and sustainable use of nature.

At the end of the meeting, the meeting adopted the "Pyeongchang Road Map," which addresses ways to achieve biodiversity through technology cooperation, funding and strengthening the capacity of developing countries.[31]

2016 COP 13

The thirteenth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place between 2 and 17 December 2016 in Cancun, Mexico.

2018 COP 14

The fourteenth ordinary meeting of the parties to the convention took place on 17–29 November 2018, in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt.[32] The 2018 UN Biodiversity Conference closed on 29 November 2018 with broad international agreement on reversing the global destruction of nature and biodiversity loss threatening all forms of life on Earth. Parties adopted the Voluntary Guidelines for the design and effective implementation of ecosystem-based approaches to climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction.[33] Governments also agreed to accelerate action to achieve the Aichi Biodiversity Targets, agreed in 2010, from now until 2020. Work to achieve these targets will take place at the global, regional, national and subnational levels.

Commemorative periods

2010 was the International Year of Biodiversity and the Secretariat of the CBD was its focal point. Following a recommendation of CBD signatories during COP 10 at Nagoya in October 2010, the UN, on 22 December 2010, declared 2011 to 2020 as the United Nations Decade on Biodiversity.

Criticism

There have been criticisms against CBD that the Convention has been weakened in implementation due to the resistance of Western countries to the implementation of the pro-South provisions of the Convention.[34] CBD is also regarded as a case of a hard treaty gone soft in the implementation trajectory.[35] The argument to enforce the treaty as a legally binding multilateral instrument with the Conference of Parties reviewing the infractions and non-compliance is also gaining strength.[36]

Although the convention explicitly states that all forms of life are covered by its provisions,[37] examination of reports and of national biodiversity strategies and action plans submitted by participating countries shows that in practice this is not happening. The fifth report of the European Union, for example, makes frequent reference to animals (particularly fish) and plants, but does not mention bacteria, fungi or protists at all.[38] The International Society for Fungal Conservation has assessed more than 100 of these CBD documents for their coverage of fungi using defined criteria to place each in one of six categories. No documents were assessed as good or adequate, less than 10% as nearly adequate or poor, and the rest as deficient, seriously deficient or totally deficient.[39]

Scientists working with biodiversity and medical research are expressing fears that the Nagoya Protocol is counterproductive, and will hamper disease prevention and conservation efforts,[40] and that the threat of imprisonment of scientists will have a chilling effect on research.[41] Non-commercial researchers and institutions such as natural history museums fear maintaining biological reference collections and exchanging material between institutions will become difficult,[42] and medical researchers have expressed alarm at plans to expand the protocol to make it illegal to publicly share genetic information, e.g. via GenBank.[43]

William Y. Brown from Brookings institutions has mentioned that the Convention on Biological Diversity should include the preservation of intact genomes and viable cells for every known species and for new species as they are discovered.[44]

See also

- 2010 Biodiversity Indicators Partnership

- 2010 Biodiversity Target

- Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPs)

- Biodiversity banking

- Biological Diversity Act, 2002

- Biopiracy

- Bioprospecting

- Biosphere Reserve

- Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals

- Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna

- Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, especially as Waterfowl Habitat

- Ecotourism

- Endangered species

- Endangered Species Recovery Plan

- Environmental agreements

- Environmental Modification Convention, another ban on weather modification / climate engineering.

- Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS)

- Green Development Initiative (GDI)

- Holocene extinction

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

- International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups

- International Organization for Biological Control

- International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture

- International Day for Biological Diversity

- International Year of Biodiversity

- Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918

- Red Data Book of Singapore

- Red Data Book of the Russian Federation

- Satoyama

- Sustainable forest management

- United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification

- United Nations Decade on Biodiversity

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

- World Conservation Monitoring Centre

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 December 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 13 December 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "History of the Convention". Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (SCBD). Archived from the original on 4 December 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- Nairobi Final Act of the Conference for the adoption of the agreed text of the Convention on Biological Diversity Archived 13 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Heinrich, M. (2002). Handbook of the Convention on Biological Diversity: Edited by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Earthscan, London, 2001. ISBN 9781853837371

- Louafi, Sélim and Jean-Frédéric Morin, International governance of biodiversity: Involving all the users of genetic resources, IDDRI, 2004, https://www.academia.edu/3809935/Louafi_S._and_J-F_Morin_2004_International_Governance_of_biodiversity_Involving_all_the_Users_of_Genetic_Resources_Les_synth%C3%A8ses_de_lIddri_n_5._4_p

- "How the Convention on Biological Diversity promotes nature and human well-being" (PDF). www.cbd.int. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. 2000. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the Convention on Biological Diversity" (PDF). www.cbd.int. Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. 2000. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 2020-07-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- "CBD List of Parties". Archived from the original on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- Hazarika, Sanjoy (23 April 1995). "India Presses U.S. to Pass Biotic Treaty". The New York Times. p. 1.13.

- Schneider, Christina J.; Urpelainen, Johannes (March 2013). "Distributional Conflict Between Powerful States and International Treaty Ratification". International Studies Quarterly. 57 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1111/isqu.12024.

- "National Biodiversity Strategies and Action Plans (NBSAPs)". Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- Watts, Jonathan (27 October 2010). "Harrison Ford calls on US to ratify treaty on conservation". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "Wayback Machine" (PDF). 6 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2013.

- "404 - Singapore Garden Photographer of the Year Photo Competition (SGPY)". 19 January 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015.

- "Text of the Nagoya Protocol". cbd.int. Convention on Biological Diversity. Archived from the original on 21 December 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- "Nagoya Protocol". Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "Meeting Documents". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Meeting Documents". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Meeting Documents". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Meeting Documents". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Meeting Documents". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Meeting Documents". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Meeting Documents". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Meeting Documents". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Eighth Ordinary Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 8)". Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- "Welcome to COP 9". Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Welcome to COP 10". Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- "World Wide Views on Biodiversity". Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 19 December 2011.

- http://www.cbd.int/cop2014; Webcasting: "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- (Source http://www.cbd.int/doc/press/2014/pr-2014-10-06-cop-12-en.pdf)

- CBD Secretariat. "COP 14 - Fourteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity". Conference of the Parties (COP). Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- CBD/COP/DEC/14/5. 30 November 2018. https://www.cbd.int/decisions/cop/?m=cop-14

- Faizi, S (2004) The Unmaking of a Treaty. Biodiversity 5(3) 2004

- Harrop, Stuart & Pritchard, Diana. (2011). A Hard Instrument Goes Soft: The Implications of the Convention on Biological Diversity's Current Trajectory. Global Environmental Change-human and Policy Dimensions - GLOBAL ENVIRON CHANGE. 21. 474-480. 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.014.

- Faizi, S (2012) CBD: Putting the focus on enforcement. Square Brackets. Issue No. 7. October, 2012

- "Text of the CBD". www.cbd.int. Archived from the original on 31 August 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "Fifth Report of the European Union to the Convention on Biological Diversity. June 2014" (PDF). www.cbd.int. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 September 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "The Micheli Guide to Fungal Conservation". www.fungal-conservation.org. Archived from the original on 19 February 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- "When the cure kills—CBD limits biodiversity research". science.sciencemag.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- "Biopiracy ban stirs red-tape fears". Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- Watanabe, Myrna E. (1 June 2015). "The Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit SharingInternational treaty poses challenges for biological collections". BioScience. 65 (6): 543–550. doi:10.1093/biosci/biv056.

- "Threats to timely sharing of pathogen sequence data". science.sciencemag.org. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- Brown, William Y. (3 August 2011). "Invest in a DNA bank for all species". Nature. 476 (7361): 399. doi:10.1038/476399a. PMID 21866143.

This article is partly based on the relevant entry in the CIA World Factbook, as of 2008 edition.

Further reading

- Davis, K. 2008. A CBD manual for botanic gardens English version, Italian version Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI)

There are indeed several comprehensive publications on the subject, the given reference covers only one small aspect

External links

- The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) website

- Text of the Convention from CBD website

- Ratifications at depositary

- Case studies on the implementation of the Convention from BGCI website with links to relevant articles

- Introductory note by Laurence Boisson de Chazournes, procedural history note and audiovisual material on the Convention on Biological Diversity in the Historic Archives of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law