Fertility and intelligence

The relationship between fertility and intelligence has been investigated in many demographic studies. There is evidence that, on a population level, intelligence is negatively correlated with fertility rate and positively correlated with survival rate of offspring.[1] The combined net effect of these two conflicting forces on ultimate population intelligence is not well studied and is unclear. It is theorized that if an inverse correlation of IQ with fertility rate were stronger than the correlation of IQ with survival rate (and if heritable factors involved in IQ were consistently expressed in populations with different fertility rates), assuming this continued over a significant number of generations, it could lead to a decrease in population IQ scores. The Flynn effect demonstrates an increase in phenotypic IQ scores over time, but confounding environmental factors during the same period of time preclude any conclusion concerning underlying change in genotypic IQ. Other correlates of IQ include income and educational attainment,[2] which are also fertility factors that are inversely correlated with fertility rate, and are to some degree heritable. Although fertility measures offspring per woman, if one needs to predict population-level changes, the average age of motherhood also needs to be considered, with lower age of motherhood potentially having a greater effect than fertility rate. (For example, a subpopulation with fertility rate of 4 with average age of reproduction at 40 years old, generally speaking, will have relatively less genotypical growth than a subpopulation with fertility rate of 3 but average age of reproduction at 20 years old.)

Early views and research

The negative correlation between fertility and intelligence (as measured by IQ) has been argued to have existed in many parts of the world. Early studies, however, were "superficial and illusory" and not clearly supported by the limited data they collected.[1]

Some of the first studies into the subject were carried out on individuals living before the advent of IQ testing, in the late 19th century, by looking at the fertility of men listed in Who's Who, these individuals being presumably of high intelligence. These men, taken as a whole, had few children, implying a correlation.[3][4]

Nobel Prize–winning physicist William Shockley controversially argued from the mid-1960s through the 1980s that "the future of the population was threatened because people with low IQs had more children than those with high IQs."[5][6]

In 1963, Weyl and Possony asserted that comparatively small differences in average intelligence can become very large differences in the very high IQ ranges. A decline in average psychometric intelligence of only a few points will mean a much smaller population of gifted individuals.[7]

More rigorous studies carried out on Americans alive after the Second World War returned different results suggesting a slight positive correlation with respect to intelligence. The findings from these investigations were consistent enough for Osborn and Bajema, writing as late as 1972, to conclude that fertility patterns were eugenic, and that "the reproductive trend toward an increase in the frequency of genes associated with higher IQ... will probably continue in the foreseeable future in the United States and will be found also in other industrial welfare-state democracies."[8]

Several reviewers considered the findings premature, arguing that the samples were nationally unrepresentative, generally being confined to whites born between 1910 and 1940 in the Great Lakes States.[9][10] Other researchers began to report a negative correlation in the 1960s after two decades of neutral or positive fertility.[11]

In 1982, Daniel R. Vining, Jr. sought to address these issues in a large study on the fertility of over 10,000 individuals throughout the United States, who were then aged 25 to 34. The average fertility in his study was correlated at −0.86 with IQ for white women and −0.96 for black women. Vining argued that this indicated a drop in the genotypic average IQ of 1.6 points per generation for the white population, and 2.4 points per generation for the black population.[12] In considering these results along with those from earlier researchers, Vining wrote that "in periods of rising birth rates, persons with higher intelligence tend to have fertility equal to, if not exceeding, that of the population as a whole," but, "The recent decline in fertility thus seems to have restored the dysgenic trend observed for a comparable period of falling fertility between 1850 and 1940." To address the concern that the fertility of this sample could not be considered complete, Vining carried out a follow-up study for the same sample 18 years later, reporting the same, though slightly decreased, negative correlation between IQ and fertility.[13]

Later research

In a 1988 study, Retherford and Sewell examined the association between the measured intelligence and fertility of over 9,000 high school graduates in Wisconsin in 1957, and confirmed the inverse relationship between IQ and fertility for both sexes, but much more so for females. If children had, on average, the same IQ as their parents, IQ would decline by .81 points per generation. Taking .71 for the additive heritability of IQ as given by Jinks and Fulker,[14] they calculated a dysgenic decline of .57 IQ points per generation.[15]

Another way of checking the negative relationship between IQ and fertility is to consider the relationship which educational attainment has to fertility, since education is known to be a reasonable proxy for IQ, correlating with IQ at .55;[16] in a 1999 study examining the relationship between IQ and education in a large national sample, David Rowe and others found not only that achieved education had a high heritability (.68) and that half of the variance in education was explained by an underlying genetic component shared by IQ, education, and SES.[17] One study investigating fertility and education carried out in 1991 found that high school dropouts in the United States had the most children (2.5 on average), with high school graduates having fewer children, and college graduates having the fewest children (1.56 on average).[18]

The Bell Curve (1994) argued that the average genotypic IQ of the United States was declining due to both dysgenetic fertility and large scale immigration of groups with low average IQ.

In a 1999 study Richard Lynn examined the relationship between the intelligence of adults aged 40 and above and their numbers of children and their siblings. Data was collected from a 1994 National Opinion Research Center survey among a representative sample of 2992 English-speaking individuals aged 18 years. He found negative correlations between the intelligence of American adults and the number of children and siblings that they had, but only for females. He also reported that there was virtually no correlation between women's intelligence and the number of children they considered ideal.[19]

In 2004 Lynn and Marian Van Court attempted a straightforward replication of Vining's work. Their study returned similar results, with the genotypic decline measuring at 0.9 IQ points per generation for the total sample and 0.75 IQ points for whites only.[20]

Boutwell et al. (2013) reported a strong negative association between county-level IQ and county-level fertility rates in the United States.[21]

A 2014 study by Satoshi Kanazawa using data from the National Child Development Study found that more intelligent women and men were more likely to want to be childless, but that only more intelligent women – not men – were more likely to actually be childless.[22]

International research

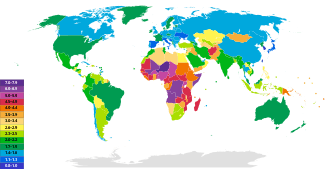

Although much of the research into intelligence and fertility has been restricted to individuals within a single nation (usually the United States), Steven Shatz (2008) extended the research internationally; he finds that "There is a strong tendency for countries with lower national IQ scores to have higher fertility rates and for countries with higher national IQ scores to have lower fertility rates."[23]

Lynn and Harvey (2008) found a correlation of −0.73 between national IQ and fertility. They estimated that the effect had been "a decline in the world's genotypic IQ of 0.86 IQ points for the years 1950–2000. A further decline of 1.28 IQ points in the world's genotypic IQ is projected for the years 2000–2050." In the first period this effect had been compensated for by the Flynn effect causing a rise in phenotypic IQ but recent studies in four developed nations had found it has now ceased or gone into reverse. They thought it probable that both genotypic and phenotypic IQ will gradually start to decline for the whole world.[24]

Possible causes

Income

A theory to explain the fertility-intelligence relationship is that while income and IQ are positively correlated,[2] income is also in itself a fertility factor that correlates inversely with fertility, that is, the higher the incomes, the lower the fertility rates and vice versa.[25][26] There is thus an inverse correlation between income and fertility within and between nations. The higher the level of education and GDP per capita of a human population, sub-population or social stratum, the fewer children are born. In a 1974 UN population conference in Bucharest, Karan Singh, a former minister of population in India, encapsulated this relationship by stating "Development is the best contraceptive".[27]

Education

People often delay childbearing in order to spend more time getting education, and thus have fewer children. Conversely, early childbearing can interfere with education, so those with early or frequent childbearing are likely to be less educated. While education and childbearing place competing demands on a person's resources, education is positively correlated with IQ.

Birth control and intelligence

Among a sample of women using birth control methods of comparable theoretical effectiveness, success rates were related to IQ, with the percentages of high, medium and low IQ women having unwanted births during a three-year interval being 3%, 8% and 11%, respectively.[28] Since the effectiveness of many methods of birth control is directly correlated with proper usage, an alternative interpretation of the data would indicate lower IQ women were less likely to use birth control consistently and correctly. Another study found that after an unwanted pregnancy has occurred, higher IQ couples are more likely to obtain abortions;[29] and unmarried teenage girls who become pregnant are found to be more likely to carry their babies to term if they are doing poorly in school.[30]

Conversely, while desired family size in the United States is apparently the same for women of all IQ levels,[31] highly educated women are found to be more likely to say that they desire more children than they have, indicating a "deficit fertility" in the highly intelligent.[32] In her review of reproductive trends in the United States, Van Court argues that "each factor – from initially employing some form of contraception, to successful implementation of the method, to termination of an accidental pregnancy when it occurs – involves selection against intelligence."[33]

Criticisms

While it may seem obvious that such differences in fertility would result in a progressive change of IQ, Preston and Campbell (1993) argued that this is a mathematical fallacy that applies only when looking at closed subpopulations. In their mathematical model, with constant differences in fertility, since children's IQ can be more or less than that of their parents, a steady-state equilibrium is argued to be established between different subpopulations with different IQ. The mean IQ will not change in the absence of a change of the fertility differences. The steady-state IQ distribution will be lower for negative differential fertility than for positive, but these differences are small. For the extreme and unrealistic assumption of endogamous mating in IQ subgroups, a differential fertility change of 2.5/1.5 to 1.5/2.5 (high IQ/low IQ) causes a maximum shift of four IQ points. For random mating, the shift is less than one IQ point.[34] James S. Coleman, however, argues that Preston and Campbell's model depends on assumptions which are unlikely to be true.[35][36]

The general increase in IQ test scores, the Flynn effect, has been argued to be evidence against dysgenic arguments. Geneticist Steve Connor wrote that Lynn, writing in Dysgenics: Genetic Deterioration in Modern Populations, "misunderstood modern ideas of genetics." "A flaw in his argument of genetic deterioration in intelligence was the widely accepted fact that intelligence as measured by IQ tests has actually increased over the past 50 years."[37] If the genes causing IQ have been adversely affected, IQ scores should reasonably be expected to change in the same direction, yet the reverse has occurred. However, it has been argued that genotypic IQ may decrease even while phenotypic IQ rises throughout the population due to environmental effects such as better nutrition and education.[15] The Flynn effect may now have ended or reversed in some developed nations.[38][39]

Some of the studies looking at relation between IQ and fertility cover the fertility of individuals who have attained a particular age, thereby ignoring positive correlation between IQ and survival. To make conclusions about effects on IQ of future populations, such effects would have to be taken into account.

Recent research has shown that education and socioeconomic status are better indicators of fertility and suggests that the relationship between intelligence and number of children may be spurious. When controlling for education and socioeconomic status, the relationship between intelligence and number of children, intelligence and number of siblings, and intelligence and ideal number of children reduces to statistical insignificance. Among women, a post-hoc analysis revealed that the lowest and highest intelligence scores did not differ significantly by number of children.[40] However, socioeconomic status and (obviously) education are themselves not independent of intelligence.

Other research suggest that siblings born further apart achieve higher educational outcomes. Therefore, sibling density, not number of siblings, may explain the negative association between IQ and number of siblings.[40]

Other traits

A study by the Institute of Psychiatry determined that men with higher IQ's tend to have better quality sperm than lower IQ males, even when considering age and lifestyle, stating that the genes underlying intelligence may be multi-factored.[41]

See also

- Dysgenics

- Fertility-development controversy

- Fertility factor (demography)

- List of countries and territories by fertility rate

Notes

- Literacy, Education and Fertility, Past and Present: A Critical Review, Harvey J. Graff

- Geary, David M. (2004). The Origin of the Mind: Evolution of Brain, Cognition, and General Intelligence. American Psychological Association (APA). ISBN 978-1-59147-181-3. OCLC 217494183.

- Huntington, E., & Whitney, L. The Builders of America. New York: Morrow, 1927.

- Kirk, Dudley. 'The fertility of a gifted group: A study of the number of children of men in WHO'S WHO.' In The Nature and Transmission of the Genetic and Cultural Characteristics of Human Populations. New York: Milbank Memorial Fund, 1957, pp.78–98.

- "William Shockley 1910–1989". A Science Odyssey People and Discoveries. PBS online. 1998. Retrieved 2006-11-13.

- William Shockley, Roger Pearson: Shockley on Eugenics and Race: The Application of Science to the Solution of Human Problems Scott-Townsend Publishers, ISBN 978-1-878465-03-0

- Weyl, N. & Possony, S. T: The Geography of Intellect, 1963, s. 154

- Osborn, F; Bajema, CJ (1972). "The eugenic hypothesis". Social Biology. 19 (4): 337–45. doi:10.1080/19485565.1972.9988006. PMID 4664670.

- Osborne, RT (1975). "Fertility, IQ and school achievement". Psychological Reports. 37 (3 PT 2): 1067–73. doi:10.2466/pr0.1975.37.3f.1067. PMID 1208722.

- Cattell, RB (1974). "Differential fertility and normal selection for IQ: some required conditions in their investigation". Social Biology. 21 (2): 168–77. doi:10.1080/19485565.1974.9988103. PMID 4439031.

- Kirk, D (1969). "The biological effects of family planning. B. The genetic implications of family planning". Journal of Medical Education. 44 (11): Suppl 2:80–3. doi:10.1097/00001888-196911000-00031. PMID 5357924.

- Vining Drj (1982). "On the possibility of the reemergence of a dysgenic trend with respect to intelligence in American fertility differentials". Intelligence. 6 (3): 241–264. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(82)90002-2. PMID 12265416.

- Vining, Daniel (1995). "On the possibility of the reemergence of a dysgenic trend with respect to intelligence in American fertility differentials: an update". Personality and Individual Differences. 19 (2): 259–263. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(95)00038-8.

- Jinks, J. L.; Fulker, D. W. (May 1970). "Comparison of the biometrical genetical, MAVA, and classical approaches to the analysis of human behavior". Psychological Bulletin. 73 (5): 311–349. doi:10.1037/h0029135. PMID 5528333. S2CID 319948.

- Retherford RD, Sewell WH (1988). "Intelligence and family size reconsidered" (PDF). Soc Biol. 35 (1–2): 1–40. doi:10.1080/19485565.1988.9988685. PMID 3217809.

- Neisser, U.; Boodoo, G.; Bouchard, T. J. , J.; Boykin, A. W.; Brody, N.; Ceci, S. J.; Halpern, D. F.; Loehlin, J. C.; Perloff, R.; Sternberg, R. J.; Urbina, S. (1996). "Intelligence: Knowns and unknowns". American Psychologist. 51 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.77. S2CID 20957095.

- Rowe, D (1998). "Herrnstein's syllogism: genetic and shared environmental influences on IQ, education, and income". Intelligence. 26 (4): 405–423. doi:10.1016/S0160-2896(99)00008-2.

- Bachu, Amara. 1991. Fertility of American Women: June 1990. U.S. Bureau of the Census. Current Population Report Series P-20, No. 454. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Lynn, R (1999). "New evidence for dysgenic fertility for intelligence in the United States". Social Biology. 46 (1–2): 146–53. doi:10.1080/19485565.1999.9988992. PMID 10842506.

- Lynn, R (2004). "New evidence of dysgenic fertility for intelligence in the United States". Intelligence. 32 (2): 193–201. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2003.09.002.

- Boutwell, Brian B.; Franklin, Travis W.; Barnes, J.C.; Beaver, Kevin M.; Deaton, Raelynn; Lewis, Richard H.; Tamplin, Amanda K.; Petkovsek, Melissa A. (2013-09-01). "County-level IQ and fertility rates: A partial test of Differential-K theory". Personality and Individual Differences. 55 (5): 547–552. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.018. ISSN 0191-8869.

- Kanazawa, Satoshi (November 2014). "Intelligence and childlessness". Social Science Research. 48: 157–170. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.06.003. PMID 25131282.

- Shatz, S. (2008). "IQ and fertility: A cross-national study". Intelligence. 36 (2): 109–111. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.03.002.

- Lynn, R.; Harvey, J. (2008). "The decline of the world's IQ". Intelligence. 36 (2): 112–120. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.03.004.

- "Income as a determinant of declining Russian fertility; Trevitt, Jamie; Public Policy; 18-Apr-2006". Archived from the original on 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- Freedman, Deborah S. (1963). "The Relation of Economic Status to Fertility". The American Economic Review. 53 (3): 414–426. JSTOR 1809165.

- David N. Weil (2004). Economic Growth. Addison-Wesley. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-201-68026-3.

- Urdry, Richard (1978). "Differential fertility by intelligence: the role of birth planning". Social Biology. 25 (1): 10–14. doi:10.1080/19485565.1978.9988313. PMID 653365.

- Cohen, Joel (1971). "Legal abortions, socioeconomic status and measured intelligence in the United States". Social Biology. 18 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1080/19485565.1971.9987900. PMID 5580587. S2CID 1843957.

- Olson, Lucy (1980). "Social and psychological correlates of pregnancy resolution among adolescent women: a review". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 50 (3): 432–445. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1980.tb03303.x. PMID 7406028.

- Vining, Daniel (1982). "On the possibility of the reemergence of a dysgenic trend with respect to intelligence in American fertility differentials". Intelligence. 6 (3): 241–264. doi:10.1016/0160-2896(82)90002-2. PMID 12265416.

- Weller, Robert H. (1974). "Excess and deficit fertility in the United States". Social Biology. 21 (l) (1): 77–87. doi:10.1080/19485565.1974.9988091. PMID 4851952.

- Van Court, Marian (1983). "Unwanted Births And Dysgenic Reproduction In The United States". Eugenics Bulletin.

- Preston SH, Campbell C (March 1993). "Differential Fertility and the Distribution of Traits: The Case of IQ". The American Journal of Sociology. 98 (5): 997–1019. doi:10.1086/230135. JSTOR 2781579.

- Coleman JS (1993). "Comment on Preston and Campbell's 'Differential Fertility and the Distribution of Traits'". The American Journal of Sociology. 98 (5): 1020–1032. doi:10.1086/230136. JSTOR 2781580.

- Lam D (March 1993). "Comment on Preston and Campbell's "Differential Fertility and the Distribution of Traits"". The American Journal of Sociology. 98 (5): 1033–1039. doi:10.1086/230137. JSTOR 2781581.

- Connor, Steve (December 22, 1996). "Stalking the Wild Taboo; Professor predicts genetic decline and fall of man". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 2008-07-23. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- Teasdale T, Owen DR (2008). "Secular declines in cognitive test scores: A reversal of the Flynn Effect". Intelligence. 36 (2): 121–126. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.01.007.

- Lynn R, Harvey J (2008). "The decline of the world's IQ". Intelligence. 36 (2): 112–120. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.03.004.

- Macon Paul Parker, Intelligence and Dysgenic Fertility: Re-specification and Reanalysis, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b06d/ef636edc0c062f687e54659ae805a8c4c793.pdf

- BBC News (2008). "Intelligent 'have better sperm'". BBC.