Biome

A biome /ˈbaɪoʊm/ is a community of plants and animals that have common characteristics for the environment they exist in. They can be found over a range of continents. Biomes are distinct biological communities that have formed in response to a shared physical climate.[1][2] Biome is a broader term than habitat; any biome can comprise a variety of habitats.

While a biome can cover large areas, a microbiome is a mix of organisms that coexist in a defined space on a much smaller scale. For example, the human microbiome is the collection of bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms that are present on or in a human body.[3]

A 'biota' is the total collection of organisms of a geographic region or a time period, from local geographic scales and instantaneous temporal scales all the way up to whole-planet and whole-timescale spatiotemporal scales. The biotas of the Earth make up the biosphere.

History of the concept

The term was suggested in 1916 by Clements, originally as a synonym for biotic community of Möbius (1877).[4] Later, it gained its current definition, based on earlier concepts of phytophysiognomy, formation and vegetation (used in opposition to flora), with the inclusion of the animal element and the exclusion of the taxonomic element of species composition.[5][6] In 1935, Tansley added the climatic and soil aspects to the idea, calling it ecosystem.[7][8] The International Biological Program (1964–74) projects popularized the concept of biome.[9]

However, in some contexts, the term biome is used in a different manner. In German literature, particularly in the Walter terminology, the term is used similarly as biotope (a concrete geographical unit), while the biome definition used in this article is used as an international, non-regional, terminology—irrespectively of the continent in which an area is present, it takes the same biome name—and corresponds to his "zonobiome", "orobiome" and "pedobiome" (biomes determined by climate zone, altitude or soil).[10]

In Brazilian literature, the term "biome" is sometimes used as synonym of "biogeographic province", an area based on species composition (the term "floristic province" being used when plant species are considered), or also as synonym of the "morphoclimatic and phytogeographical domain" of Ab'Sáber, a geographic space with subcontinental dimensions, with the predominance of similar geomorphologic and climatic characteristics, and of a certain vegetation form. Both include many biomes in fact.[5][11][12]

Classifications

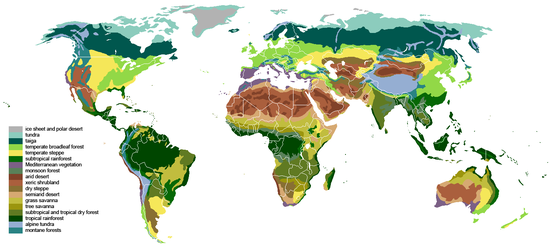

To divide the world in a few ecological zones is a difficult attempt, notably because of the small-scale variations that exist everywhere on earth and because of the gradual changeover from one biome to the other. Their boundaries must therefore be drawn arbitrarily and their characterization made according to the average conditions that predominate in them.[13]

A 1978 study on North American grasslands[14] found a positive logistic correlation between evapotranspiration in mm/yr and above-ground net primary production in g/m2/yr. The general results from the study were that precipitation and water use led to above-ground primary production, while solar irradiation and temperature lead to below-ground primary production (roots), and temperature and water lead to cool and warm season growth habit.[15] These findings help explain the categories used in Holdridge's bioclassification scheme (see below), which were then later simplified by Whittaker. The number of classification schemes and the variety of determinants used in those schemes, however, should be taken as strong indicators that biomes do not fit perfectly into the classification schemes created.

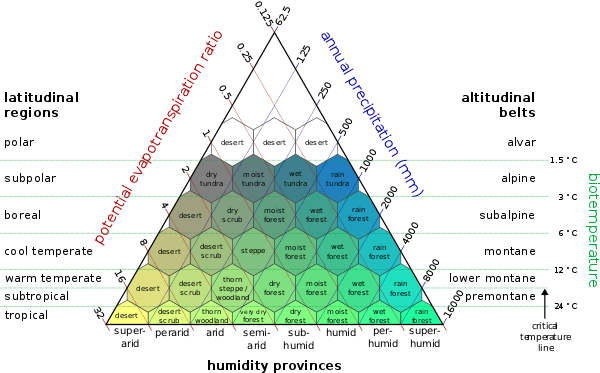

Holdridge (1947, 1964) life zones

Holdridge classified climates based on the biological effects of temperature and rainfall on vegetation under the assumption that these two abiotic factors are the largest determinants of the types of vegetation found in a habitat. Holdridge uses the four axes to define 30 so-called "humidity provinces", which are clearly visible in his diagram. While this scheme largely ignores soil and sun exposure, Holdridge acknowledged that these were important.

Allee (1949) biome-types

The principal biome-types by Allee (1949):[16]

Kendeigh (1961) biomes

The principal biomes of the world by Kendeigh (1961):[17]

- Terrestrial

- Temperate deciduous forest

- Coniferous forest

- Woodland

- Chaparral

- Tundra

- Grassland

- Desert

- Tropical savanna

- Tropical forest

- Marine

- Oceanic plankton and nekton

- Balanoid-gastropod-thallophyte

- Pelecypod-annelid

- Coral reef

Whittaker (1962, 1970, 1975) biome-types

Whittaker classified biomes using two abiotic factors: precipitation and temperature. His scheme can be seen as a simplification of Holdridge's; more readily accessible, but missing Holdridge's greater specificity.

Whittaker based his approach on theoretical assertions and empirical sampling. He was in a unique position to make such a holistic assertion because he had previously compiled a review of biome classifications.[18]

Key definitions for understanding Whittaker's scheme

- Physiognomy: the apparent characteristics, outward features, or appearance of ecological communities or species.

- Biome: a grouping of terrestrial ecosystems on a given continent that is similar in vegetation structure, physiognomy, features of the environment and characteristics of their animal communities.

- Formation: a major kind of community of plants on a given continent.

- Biome-type: grouping of convergent biomes or formations of different continents, defined by physiognomy.

- Formation-type: a grouping of convergent formations.

Whittaker's distinction between biome and formation can be simplified: formation is used when applied to plant communities only, while biome is used when concerned with both plants and animals. Whittaker's convention of biome-type or formation-type is simply a broader method to categorize similar communities.[19]

Whittaker's parameters for classifying biome-types

Whittaker, seeing the need for a simpler way to express the relationship of community structure to the environment, used what he called "gradient analysis" of ecocline patterns to relate communities to climate on a worldwide scale. Whittaker considered four main ecoclines in the terrestrial realm.[19]

- Intertidal levels: The wetness gradient of areas that are exposed to alternating water and dryness with intensities that vary by location from high to low tide

- Climatic moisture gradient

- Temperature gradient by altitude

- Temperature gradient by latitude

Along these gradients, Whittaker noted several trends that allowed him to qualitatively establish biome-types:

- The gradient runs from favorable to the extreme, with corresponding changes in productivity.

- Changes in physiognomic complexity vary with how favorable of an environment exists (decreasing community structure and reduction of stratal differentiation as the environment becomes less favorable).

- Trends in the diversity of structure follow trends in species diversity; alpha and beta species diversities decrease from favorable to extreme environments.

- Each growth-form (i.e. grasses, shrubs, etc.) has its characteristic place of maximum importance along the ecoclines.

- The same growth forms may be dominant in similar environments in widely different parts of the world.

Whittaker summed the effects of gradients (3) and (4) to get an overall temperature gradient and combined this with a gradient (2), the moisture gradient, to express the above conclusions in what is known as the Whittaker classification scheme. The scheme graphs average annual precipitation (x-axis) versus average annual temperature (y-axis) to classify biome-types.

Biome-types

- Tropical rainforest

- Tropical seasonal rainforest

- deciduous

- semideciduous

- Temperate giant rainforest

- Montane rainforest

- Temperate deciduous forest

- Temperate evergreen forest

- needleleaf

- sclerophyll

- Subarctic-subalpin needle-leaved forests (taiga)

- Elfin woodland

- Thorn forests and woodlands

- Thorn scrub

- Temperate woodland

- Temperate shrublands

- deciduous

- heath

- sclerophyll

- subalpine-needleleaf

- subalpine-broadleaf

- Savanna

- Temperate grassland

- Alpine grasslands

- Tundra

- Tropical desert

- Warm-temperate desert

- Cool temperate desert scrub

- Arctic-alpine desert

- Bog

- Tropical fresh-water swamp forest

- Temperate fresh-water swamp forest

- Mangrove swamp

- Salt marsh

- Wetland[20]

Goodall (1974–) ecosystem types

The multiauthored series Ecosystems of the world, edited by David W. Goodall, provides a comprehensive coverage of the major "ecosystem types or biomes" on earth:[21]

- Terrestrial Ecosystems

- Natural Terrestrial Ecosystems

- Wet Coastal Ecosystems

- Dry Coastal Ecosystems

- Polar and Alpine Tundra

- Mires: Swamp, Bog, Fen, and Moor

- Temperate Deserts and Semi-Deserts

- Coniferous Forests

- Temperate Deciduous Forests

- Natural Grasslands

- Heathlands and Related Shrublands

- Temperate Broad-Leaved Evergreen Forests

- Mediterranean-Type Shrublands

- Hot Deserts and Arid Shrublands

- Tropical Savannas

- Tropical Rain Forest Ecosystems

- Wetland Forests

- Ecosystems of Disturbed Ground

- Managed Terrestrial Ecosystems

- Managed Grasslands

- Field Crop Ecosystems

- Tree Crop Ecosystems

- Greenhouse Ecosystems

- Bioindustrial Ecosystems

- Natural Terrestrial Ecosystems

- Aquatic Ecosystems

- Inland Aquatic Ecosystems

- River and Stream Ecosystems

- Lakes and Reservoirs

- Marine Ecosystems

- Intertidal and Littoral Ecosystems

- Coral Reefs

- Estuaries and Enclosed Seas

- Ecosystems of the Continental Shelves

- Ecosystems of the Deep Ocean

- Managed Aquatic Ecosystems

- Managed Aquatic Ecosystems

- Inland Aquatic Ecosystems

- Underground Ecosystems

- Cave Ecosystems

Walter (1976, 2002) zonobiomes

The eponymously-named Heinrich Walter classification scheme considers the seasonality of temperature and precipitation. The system, also assessing precipitation and temperature, finds nine major biome types, with the important climate traits and vegetation types. The boundaries of each biome correlate to the conditions of moisture and cold stress that are strong determinants of plant form, and therefore the vegetation that defines the region. Extreme conditions, such as flooding in a swamp, can create different kinds of communities within the same biome.[10][22][23]

| Zonobiome | Zonal soil type | Zonal vegetation type |

|---|---|---|

| ZB I. Equatorial, always moist, little temperature seasonality | Equatorial brown clays | Evergreen tropical rainforest |

| ZB II. Tropical, summer rainy season and cooler “winter” dry season | Red clays or red earths | Tropical seasonal forest, seasonal dry forest, scrub, or savanna |

| ZB III. Subtropical, highly seasonal, arid climate | Serosemes, sierozemes | Desert vegetation with considerable exposed surface |

| ZB IV. Mediterranean, winter rainy season and summer drought | Mediterranean brown earths | Sclerophyllous (drought-adapted), frost-sensitive shrublands and woodlands |

| ZB V. Warm temperate, occasional frost, often with summer rainfall maximum | Yellow or red forest soils, slightly podsolic soils | Temperate evergreen forest, somewhat frost-sensitive |

| ZB VI. Nemoral, moderate climate with winter freezing | Forest brown earths and grey forest soils | Frost-resistant, deciduous, temperate forest |

| ZB VII. Continental, arid, with warm or hot summers and cold winters | Chernozems to serozems | Grasslands and temperate deserts |

| ZB VIII. Boreal, cold temperate with cool summers and long winters | Podsols | Evergreen, frost-hardy, needle-leaved forest (taiga) |

| ZB IX. Polar, short, cool summers and long, cold winters | Tundra humus soils with solifluction (permafrost soils) | Low, evergreen vegetation, without trees, growing over permanently frozen soils |

Schultz (1988) ecozones

Schultz (1988) defined nine ecozones (note that his concept of ecozone is more similar to the concept of biome used in this article than to the concept of ecozone of BBC):[24]

- polar/subpolar zone

- boreal zone

- humid mid-latitudes

- arid mid-latitudes

- tropical/subtropical arid lands

- Mediterranean-type subtropics

- seasonal tropics

- humid subtropics

- humid tropics

Bailey (1989) ecoregions

Robert G. Bailey nearly developed a biogeographical classification system of ecoregions for the United States in a map published in 1976. He subsequently expanded the system to include the rest of North America in 1981, and the world in 1989. The Bailey system, based on climate, is divided into seven domains (polar, humid temperate, dry, humid, and humid tropical), with further divisions based on other climate characteristics (subarctic, warm temperate, hot temperate, and subtropical; marine and continental; lowland and mountain).[25][26]

- 100 Polar Domain

- 200 Humid Temperate Domain

- 210 Warm Continental Division (Köppen: portion of Dcb)

- M210 Warm Continental Division – Mountain Provinces

- 220 Hot Continental Division (Köppen: portion of Dca)

- M220 Hot Continental Division – Mountain Provinces

- 230 Subtropical Division (Köppen: portion of Cf)

- M230 Subtropical Division – Mountain Provinces

- 240 Marine Division (Köppen: Do)

- M240 Marine Division – Mountain Provinces

- 250 Prairie Division (Köppen: arid portions of Cf, Dca, Dcb)

- 260 Mediterranean Division (Köppen: Cs)

- M260 Mediterranean Division – Mountain Provinces

- 300 Dry Domain

- 310 Tropical/Subtropical Steppe Division

- M310 Tropical/Subtropical Steppe Division – Mountain Provinces

- 320 Tropical/Subtropical Desert Division

- 330 Temperate Steppe Division

- 340 Temperate Desert Division

- 400 Humid Tropical Domain

- 410 Savanna Division

- 420 Rainforest Division

Olson & Dinerstein (1998) biomes for WWF / Global 200

A team of biologists convened by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) developed a scheme that divided the world's land area into biogeographic realms (called "ecozones" in a BBC scheme), and these into ecoregions (Olson & Dinerstein, 1998, etc.). Each ecoregion is characterized by a main biome (also called major habitat type).[27][28]

This classification is used to define the Global 200 list of ecoregions identified by the WWF as priorities for conservation.[27]

For the terrestrial ecoregions, there is a specific EcoID, format XXnnNN (XX is the biogeographic realm, nn is the biome number, NN is the individual number).

Biogeographic realms (terrestrial and freshwater)

- NA: Nearctic

- PA: Palearctic

- AT: Afrotropic

- IM: Indomalaya

- AA: Australasia

- NT: Neotropic

- OC: Oceania

- AN: Antarctic[28]

The applicability of the realms scheme above - based on Udvardy (1975)—to most freshwater taxa is unresolved.[29]

Biogeographic realms (marine)

Biomes (terrestrial)

- Tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests (tropical and subtropical, humid)

- Tropical and subtropical dry broadleaf forests (tropical and subtropical, semihumid)

- Tropical and subtropical coniferous forests (tropical and subtropical, semihumid)

- Temperate broadleaf and mixed forests (temperate, humid)

- Temperate coniferous forests (temperate, humid to semihumid)

- Boreal forests/taiga (subarctic, humid)

- Tropical and subtropical grasslands, savannas, and shrublands (tropical and subtropical, semiarid)

- Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands (temperate, semiarid)

- Flooded grasslands and savannas (temperate to tropical, fresh or brackish water inundated)

- Montane grasslands and shrublands (alpine or montane climate)

- Tundra (Arctic)

- Mediterranean forests, woodlands, and scrub or sclerophyll forests (temperate warm, semihumid to semiarid with winter rainfall)

- Deserts and xeric shrublands (temperate to tropical, arid)

- Mangrove (subtropical and tropical, salt water inundated)[28]

Biomes (freshwater)

According to the WWF, the following are classified as freshwater biomes:[31]

- Large lakes

- Large river deltas

- Polar freshwaters

- Montane freshwaters

- Temperate coastal rivers

- Temperate floodplain rivers and wetlands

- Temperate upland rivers

- Tropical and subtropical coastal rivers

- Tropical and subtropical floodplain rivers and wetlands

- Tropical and subtropical upland rivers

- Xeric freshwaters and endorheic basins

- Oceanic islands

Biomes (marine)

Biomes of the coastal and continental shelf areas (neritic zone):

- Polar

- Temperate shelves and sea

- Temperate upwelling

- Tropical upwelling

- Tropical coral[32]

Summary of the scheme

- Biosphere

- Biogeographic realms (terrestrial) (8)

- Ecoregions (867), each characterized by a main biome type (14)

- Biogeographic realms (terrestrial) (8)

- Biosphere

- Biogeographic realms (freshwater) (8)

- Ecoregions (426), each characterized by a main biome type (12)

- Ecosystems (biotopes)

- Ecoregions (426), each characterized by a main biome type (12)

- Biogeographic realms (freshwater) (8)

- Biosphere

- Biogeographic realms (marine) (12)

- (Marine provinces) (62)

- Ecoregions (232), each characterized by a main biome type (5)

- Ecosystems (biotopes)

- Ecoregions (232), each characterized by a main biome type (5)

- (Marine provinces) (62)

- Biogeographic realms (marine) (12)

Example:

- Biosphere

- Biogeographic realm: Palearctic

- Ecoregion: Dinaric Mountains mixed forests (PA0418); biome type: temperate broadleaf and mixed forests

- Ecosystem: Orjen, vegetation belt between 1,100–1,450 m, Oromediterranean zone, nemoral zone (temperate zone)

- Biotope: Oreoherzogio-Abietetum illyricae Fuk. (Plant list)

- Plant: Silver fir (Abies alba)

- Biotope: Oreoherzogio-Abietetum illyricae Fuk. (Plant list)

- Ecosystem: Orjen, vegetation belt between 1,100–1,450 m, Oromediterranean zone, nemoral zone (temperate zone)

- Ecoregion: Dinaric Mountains mixed forests (PA0418); biome type: temperate broadleaf and mixed forests

- Biogeographic realm: Palearctic

Other biomes

Marine biomes

Pruvot (1896) zones or "systems":[33]

- Coastal

- Polar

- Trade wind

- Westerly

Other marine habitat types (not covered yet by the Global 200/WWF scheme):

- Open sea

- Deep sea

- Hydrothermal vents

- Cold seeps

- Benthic zone

- Pelagic zone (trades and westerlies)

- Abyssal

- Hadal (ocean trench)

- Littoral/Intertidal zone

- Salt marsh

- Estuaries

- Coastal lagoons/Atoll lagoons

- Kelp forest

- Pack ice

Anthropogenic biomes

Humans have altered global patterns of biodiversity and ecosystem processes. As a result, vegetation forms predicted by conventional biome systems can no longer be observed across much of Earth's land surface as they have been replaced by crop and rangelands or cities. Anthropogenic biomes provide an alternative view of the terrestrial biosphere based on global patterns of sustained direct human interaction with ecosystems, including agriculture, human settlements, urbanization, forestry and other uses of land. Anthropogenic biomes offer a new way forward in ecology and conservation by recognizing the irreversible coupling of human and ecological systems at global scales and moving us toward an understanding of how best to live in and manage our biosphere and the anthropogenic biomes we live in.

Major anthropogenic biomes:

- Dense settlements

- Croplands

- Rangelands

- Forested

- Indoor[35]

Microbial biomes

Endolithic biomes

The endolithic biome, consisting entirely of microscopic life in rock pores and cracks, kilometers beneath the surface, has only recently been discovered, and does not fit well into most classification schemes.[36]

See also

- Biomics

- Ecosystem – A community of living organisms together with the nonliving components of their environment

- Ecotope – The smallest ecologically distinct landscape features in a landscape mapping and classification system

- Climate classification

- Life zones

- Natural environment – All living and non-living things occurring naturally, generally on Earth

References

- "The world's biomes". www.ucmp.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 2008-12-04. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- Cain, Michael; Bowman, William; Hacker, Sally (2014). Ecology (Third ed.). Massachusetts: Sinauer. p. 51. ISBN 9780878939084.

- "Finally, A Map Of All The Microbes On Your Body". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2018-04-16. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- Clements, F. E. 1917. The development and structure of biotic communities. J. Ecology 5:120–121. Abstract of a talk in 1916, Archived 2016-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- Coutinho, L. M. (2006). O conceito de bioma. Acta Bot. Bras. 20(1): 13–23, Archived 2016-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- Martins, F. R. & Batalha, M. A. (2011). Formas de vida, espectro biológico de Raunkiaer e fisionomia da vegetação. In: Felfili, J. M., Eisenlohr, P. V.; Fiuza de Melo, M. M. R.; Andrade, L. A.; Meira Neto, J. A. A. (Org.). Fitossociologia no Brasil: métodos e estudos de caso. Vol. 1. Viçosa: Editora UFV. pp. 44–85. Archived 2016-09-24 at the Wayback Machine. Earlier version, 2003, Archived 2016-08-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- Cox, C. B., Moore, P.D. & Ladle, R. J. 2016. Biogeography: an ecological and evolutionary approach. 9th edition. John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, p. 20, Archived 2016-11-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- Tansley, A.G. (1935). The use and abuse of vegetational terms and concepts. Ecology 16 (3): 284–307, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-10-06. Retrieved 2016-09-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Box, E.O. & Fujiwara, K. (2005). Vegetation types and their broad-scale distribution. In: van der Maarel, E. (ed.). Vegetation ecology. Blackwell Scientific, Oxford. pp. 106–128, Archived 2016-08-28 at the Wayback Machine.

- Walter, H. & Breckle, S-W. (2002). Walter's Vegetation of the Earth: The Ecological Systems of the Geo-Biosphere. New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 86, Archived 2016-11-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- Batalha, M.A. (2011). The Brazilian cerrado is not a biome. Biota Neotrop. 11:21–24, Archived 2016-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- Fiaschi, P.; Pirani, J.R. 2009. Review of plant biogeographic studies in Brazil. Journal of Systematics and Evolution, v. 47, pp. 477–496. Disponível em: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/249500929_Review_of_plant_biogeographic_studies_in_Brazil Archived 2017-08-31 at the Wayback Machine>.

- Schultz, Jürgen (1995). The ecozones of the world. pp. 2–3. ISBN 3540582932.

- Sims, Phillip L.; Singh, J.S. (July 1978). "The Structure and Function of Ten Western North American Grasslands: III. Net Primary Production, Turnover and Efficiencies of Energy Capture and Water Use". Journal of Ecology. British Ecological Society. 66 (2): 573–597. doi:10.2307/2259152. JSTOR 2259152.

- Pomeroy, Lawrence R. and James J. Alberts, editors. Concepts of Ecosystem Ecology. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1988.

- Allee, W.C. (1949). Principles of animal ecology. Philadelphia, Saunders Co., Archived 2017-10-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- Kendeigh, S.C. (1961). Animal ecology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall

- Whittaker, Robert H., Botanical Review, Classification of Natural Communities, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Jan–Mar 1962), pp. 1–239.

- Whittaker, Robert H. Communities and Ecosystems. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, Inc., 1975.

- Whittaker, R. H. (1970). Communities and Ecosystems. Toronto, pp. 51–64, .

- Goodall, D. W. (editor-in-chief). Ecosystems of the World. Elsevier, Amsterdam. 36 vol., 1974–, Archived 2016-09-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- Walter, H. 1976. Die ökologischen Systeme der Kontinente (Biogeosphäre). Prinzipien ihrer Gliederung mit Beispielen. Stuttgart.

- Walter, H. & Breckle, S-W. (1991). Ökologie der Erde, Band 1, Grundlagen. Stuttgart.

- Schultz, J. Die Ökozonen der Erde, 1st ed., Ulmer, Stuttgart, Germany, 1988, 488 pp.; 2nd ed., 1995, 535 pp.; 3rd ed., 2002. Transl.: The Ecozones of the World: The Ecological Divisions of the Geosphere. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1995; 2nd ed., 2005, .

- http://www.fs.fed.us/land/ecosysmgmt/index.html Archived 2009-01-01 at the Wayback Machine Bailey System, US Forest Service

- Bailey, R. G. 1989. Explanatory supplement to ecoregions map of the continents. Environmental Conservation 16: 307–309. [With map of land-masses of the world, "Ecoregions of the Continents – Scale 1 : 30,000,000", published as a supplement.]

- Olson, D. M. & E. Dinerstein (1998). The Global 200: A representation approach to conserving the Earth’s most biologically valuable ecoregions. Conservation Biol. 12:502–515, Archived 2016-10-07 at the Wayback Machine.

- Olson, D. M., Dinerstein, E., Wikramanayake, E. D., Burgess, N. D., Powell, G. V. N., Underwood, E. C., D'Amico, J. A., Itoua, I., Strand, H. E., Morrison, J. C., Loucks, C. J., Allnutt, T. F., Ricketts, T. H., Kura, Y., Lamoreux, J. F., Wettengel, W. W., Hedao, P., Kassem, K. R. (2001). Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: a new map of life on Earth. Bioscience 51(11):933–938, Archived 2012-09-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- Abell, R., M. Thieme, C. Revenga, M. Bryer, M. Kottelat, N. Bogutskaya, B. Coad, N. Mandrak, S. Contreras-Balderas, W. Bussing, M. L. J. Stiassny, P. Skelton, G. R. Allen, P. Unmack, A. Naseka, R. Ng, N. Sindorf, J. Robertson, E. Armijo, J. Higgins, T. J. Heibel, E. Wikramanayake, D. Olson, H. L. Lopez, R. E. d. Reis, J. G. Lundberg, M. H. Sabaj Perez, and P. Petry. (2008). Freshwater ecoregions of the world: A new map of biogeographic units for freshwater biodiversity conservation. BioScience 58:403–414, Archived 2016-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- Spalding, M. D. et al. (2007). Marine ecoregions of the world: a bioregionalization of coastal and shelf areas. BioScience 57: 573–583, Archived 2016-10-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Freshwater Ecoregions of the World: Major Habitat Types" "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. Retrieved 2008-05-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link). Accessed May 12, 2008.

- WWF: Marine Ecoregions of the World Archived 2009-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Pruvot, G. Conditions générales de la vie dans les mers et principes de distribution des organismes marins: Année Biologique, vol. 2, pp. 559—587, 1896, Archived 2016-10-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- Longhurst, A. 1998. Ecological Geography of the Sea. San Diego: Academic Press, .

- Zimmer, Carl (March 19, 2015). "The Next Frontier: The Great Indoors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved March 2015. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - "What is the Endolithic Biome? (with picture)". wiseGEEK. Archived from the original on 2017-03-07. Retrieved 2017-03-07.

External links

| Look up Biome in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Biomes and ecosystems. |

- "Biomes". Encyclopedia of Earth.

- Biomes of the world (Missouri Botanic Garden)

- Global Currents and Terrestrial Biomes Map

- WorldBiomes.com is a site covering the 5 principal world biome types: aquatic, desert, forest, grasslands, and tundra.

- UWSP's online textbook The Physical Environment: – Earth Biomes

- Panda.org's Habitats – describes the 14 major terrestrial habitats, 7 major freshwater habitats, and 5 major marine habitats.

- Panda.org's Habitats Simplified – provides simplified explanations for 10 major terrestrial and aquatic habitat types.

- UCMP Berkeley's The World's Biomes – provides lists of characteristics for some biomes and measurements of climate statistics.

- Gale/Cengage has an excellent Biome Overview of terrestrial, aquatic, and man-made biomes with a particular focus on trees native to each, and has detailed descriptions of desert, rain forest, and wetland biomes.

- Islands Of Wildness, The Natural Lands Of North America by Jim Bones, a video about continental biomes and climate change.

- Dreams Of The Earth, Love Songs For A Troubled Planet by Jim Bones, a poetic video about the North American Biomes and climate change.

- NASA's Earth Observatory Mission: Biomes gives an exemplar of each biome that is described in detail and provides scientific measurements of the climate statistics that define each biome.