Development aid

Development aid or development cooperation (also development assistance, technical assistance, international aid, overseas aid, official development assistance (ODA), or foreign aid) is financial aid given by governments and other agencies to support the economic, environmental, social, and political development of developing countries. It can be further defined as "aid expended in a manner that is anticipated to promote development, whether achieved through economic growth or other means".[1] It is distinguished from humanitarian aid by focusing on alleviating poverty in the long term, rather than a short term response.

The term development cooperation, which is used the World Health Organization (WHO), is used to express the idea that a partnership should exist between donor and recipient, rather than the traditional situation in which the relationship was dominated by the wealth and specialised knowledge of one side.[2]

Aid may be bilateral: given from one country directly to another; or it may be multilateral: given by the donor country to an international organisation such as the World Bank or the United Nations Agencies (UNDP, UNICEF, UNAIDS, etc.) which then distributes it among the developing countries. The proportion is currently about 70% bilateral 30% multilateral.[3]

About 80–85% of developmental aid comes from government sources as official development assistance (ODA). The remaining 15–20% comes from private organisations such as "non-governmental organisations" (NGOs), foundations and other development charities (e.g., Oxfam).[4] In addition, remittances received from migrants working or living in diaspora form a significant amount of international transfer. Most development aid comes from the Western industrialised countries but some poorer countries also contribute aid. Some governments also include military assistance in the notion "foreign aid", although many NGOs tend to disapprove of this.

Official development assistance is a measure of government-contributed aid, compiled by the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) since 1969. The DAC consists of 34 of the largest aid-donating countries.

History

Origins

The concept of development aid goes back to the colonial era at the turn of the twentieth century, in particular to the British policy of colonial development that emerged during that period. The traditional government policy had tended to favor laissez-faire style economics, with the free market for capital and goods dictating the economic role that colonies played in the British Empire.

Changes in attitudes towards the moral purpose of the Empire, and the role that government could play in the promotion of welfare slowly led to a more proactive policy of economic and developmental assistance towards poor colonies. The first challenge to Britain was the economic crisis that occurred after World War I. Prior to the passage of the 1929 Colonial Development Act, the doctrine that governed Britain (and other European colonizers) with their territories was that of financial self-sufficiency. What this simply meant was that the colonies were responsible for themselves.[5]

Britain was not going to use the money that belongs to the metropole to pay for things in the colonies. The colonies did not only have to pay for infrastructural development but they also were responsible for the salaries of British officials that worked in the colonies. The colonies generated the revenues to pay for these through different forms of taxations. The standard taxation was the import and export taxes. Goods going out of the colonies were taxed and those coming in were also taxed. These generate significant revenues. Apart from these taxes, the colonizers introduced two other forms of taxes: hut tax and labor tax. The hut tax is akin to a property tax today. Every grown up adult male had their own hut. Each of these had to pay a tax. Labor tax was the work that the people had to do without any remunerations or with meager stipends.[6] As the economic crisis widened and had significant impact on the colonies, revenues generated from taxes continued to decline, having a significant impact on the colonies. While this was going on, Britain experienced major unemployment rates. Parliament began to discuss ways in which they could deal with Britain's unemployment rates and at the same time respond to some of the urgent needs of the colonies.[7] This process culminated in the passage of the Colonial Development Act in 1929, which established a Colonial Development Advisory Committee under the authority of the Secretary of State for the Colonies, then Lord Passfield. Its initial annual budget of £1 million was spent on schemes designed to develop the infrastructure of transport, electrical power and water supply in colonies and dominions abroad for the furtherance of imperial trade.[8] The 1929 Act, though meager in the resources it made available for development, was a significant Act because it opened the door for Britain to make future investments in the colonies. It was a major shift in colonial development. The doctrine of financial self-sufficiency was abandoned and Britain could now use metropolitan funds to develop the colonies.

By the late 1930s, especially after the British West Indian labour unrest of 1934–1939, it was clear that this initial scheme was far too limited in scope. A Royal Commission under Lord Moyne was sent to investigate the living conditions in the British West Indies and it published its Report in 1940 which exposed the horrendous living conditions there.[9][10]

Amidst increasing criticism of Britain's colonial policies from abroad and at home,[11][12] the commission was a performance to showcase Britain's "benevolent" attitude towards its colonial subjects.[13] The Commission's recommendations urged health and education initiatives along with increased sugar subsidies to stave off a complete and total economic meltdown.[14] The Colonial Office, eager to prevent instability while the country was at war, began funneling large sums of cash into the region.[15]

The Colonial Development and Welfare Act was passed in 1940 to organize and allocate a sum of £5 million per year to the British West Indies for the purpose of long-term development. Some £10 million in loans was cancelled in the same Act.[16] The Colonial Development and Welfare Act of 1945 increased the level of aid to £120m over a twenty-year period. Further Acts followed in 1948, 1959 and 1963, dramatically increasing the scope of monetary assistance, favourable interest-free loans and development assistance programs.

Postwar expansion

The beginning of modern development aid is rooted in the context of Post-World War II and the Cold War. Launched as a large-scale aid program by the United States in 1948, the European Recovery Program, or Marshall Plan, was concerned with strengthening the ties to the West European states to contain the influence of the USSR. Implemented by the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA), the Marshall Plan also expanded its reconstruction finance to strategic parts of the Middle East and Asia.[17] The rationale was well summarized in the 'Point Four Program', in which United States president Harry Truman stated the anti-communist rationale for U.S. development aid in his inaugural address of 1949, which also announced the founding of NATO:[8]

- "In addition, we will provide military advice and equipment to free nations which will cooperate with us in the maintenance of peace and security. Fourth, we must embark on a bold new program for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas. More than half the people of the world are living in conditions approaching misery. Their food is inadequate. They are victims of disease. Their economic life is primitive and stagnant. Their poverty is a handicap and a threat both to them and to more prosperous areas. For the first time in history, humanity possesses the knowledge and skill to relieve the suffering of these people."[18]

In 1951, the Technical Cooperation Administration (TCA) was established within the Department of State to run the Point Four program. Development aid was aimed at offering technical solutions to social problems without altering basic social structures. The United States was often fiercely opposed to even moderate changes in social structures, for example the land reform in Guatemala in the early 1950s.

In 1953 at the end of the Korean War, the incoming Eisenhower Administration established the Foreign Operations Administration (FOA) as an independent government agency outside the Department of State to consolidate economic and technical assistance. In 1955, foreign aid was brought back under the administrative control of the Department of State and FOA was renamed the International Cooperation Administration (ICA).

In 1956, the Senate conducted a study of foreign aid with the help of a number of independent experts. The result, stated in a 1959 amendment to the Mutual Security Act, declared that development in low-income regions was a U.S. objective along with and additional to other foreign-policy interests, attempting thus to clarify development assistance's relationship with the effort to contain Communism. In 1961, the Congress approved the Foreign Assistance Act of 1961 with President J.F. Kennedy's support, which retained the 1959 policy of international development as an independent U.S. objective and set up a new Agency for International Development, USAID.

The volume of international aid to developing countries (called "Third World" at the time) grew dramatically from the 1960s. This aid came mainly from the US and Western European countries, but there were also significant contributions from the Soviet Union in exchange for overseas political influence in the context of the heightened global tensions of the Cold War.

The practice of extending aid to politically aligned parties in recipient nations continues today; Faye and Niehaus (2012) are able to establish a causal relationship between politics and aid in recipient nations.[19] In their analysis of the competitive 2006 Palestinian elections, they note that USAID provided funding for development programs in Palestine to support the Palestinian Authority, the US backed entity running for reelection. Faye and Niehaus discovered that the greater the degree of alignment the recipient party has with the donor entity, the more aid it receives on average during an election year.[19] In an analysis of the 3 biggest donor nations (Japan, France, and the US), Alesina and Dollar (2000) discovered that each has its own distortions to the aid it gives out.[20] Japan appears to prioritize giving aid nations that exercise similar voting preferences in the United Nations, France mostly sends aid to its former colonies, and the U.S. disproportionately provides aid to Israel and Egypt.[20] These allocations are often powerful tools for maintaining the strategic interests of the donor country in the recipient country.

The Development Assistance Committee was established in 1960 by the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation to coordinate development aid amongst the rich nations. A 1961 resolution decreed that:

The Committee will continue to consult on the methods for making national resources available for assisting countries and areas in the process of economic development and for expanding and improving the flow of long-term funds and other development assistance to them.

— Development Assistance Committee, Mandate (1961)

Critiques of development aid

Development aid is often provided by means of supporting local development aid projects. In these projects, it sometimes occurs that no strict code of conduct is in force. In some projects, the development aid workers do not respect the local code of conduct. For example, the local dress code as well as social interaction. In developing countries, these matters are regarded highly important and not respecting it may cause severe offense, and thus significant problems and delay of the projects.

There is also much debate about evaluating the quality of development aid, rather than simply the quantity. For instance, tied aid is often criticized as the aid given must be spent in the donor country or in a group of selected countries. Tied aid can increase development aid project costs by up to 20 or 30 percent.[21]

There is also criticism because donors may give with one hand, through large amounts of development aid, yet take away with the other, through strict trade or migration policies, or by getting a foothold for foreign corporations. The Commitment to Development Index measures the overall policies of donors and evaluates the quality of their development aid, instead of just comparing the quantity of official development assistance given.

Extent of aid

| Development economics |

|---|

|

| Economies by region |

| Economic growth theories |

|

| Fields and subfields |

| Lists |

|

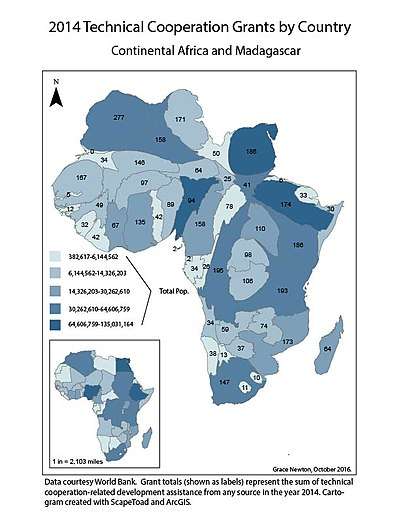

Most official development assistance (ODA) comes from the 28 members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), or about $135 billion in 2013. A further $15.9 billion came from the European Commission and non-DAC countries gave an additional $9.4 billion. Although development aid rose in 2013 to the highest level ever recorded, a trend of a falling share of aid going to the neediest sub-Saharan African countries continued.[22]

Top recipient countries

| Country | US$, billions |

|---|---|

| 4.82 | |

| 4.22 | |

| 4.2 | |

| 3.61 | |

| 3.59 | |

| 3.53 | |

| 3.44 | |

| 2.98 | |

| 2.7 | |

| 2.67 |

Top donor countries

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) measures countries contributing the highest amounts of ODA (in absolute terms). As of 2013, the top 10 DAC countries are as follows (listed in US dollars). European Union countries together gave $70.73 billion and EU Institutions gave a further $15.93 billion.[22][24] The European Union accumulated a higher portion of GDP as a form of foreign aid than any other economic union.[25]

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

The OECD also lists countries by the amount of ODA they give as a percentage of their gross national income. The top 10 DAC countries are as follows. Five countries met the longstanding UN target for an ODA/GNI ratio of 0.7% in 2013:[22]

.svg.png)

European Union countries that are members of the Development Assistance Committee gave 0.42% of GNI (excluding the $15.93 billion given by EU Institutions).[22]

By type of project

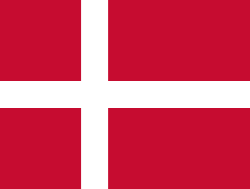

Total official development assistance (ODA) and other official flows from all donors in support of infrastructure in 2017

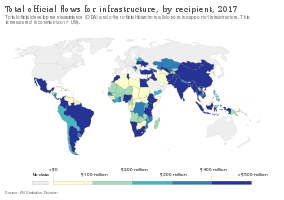

Total official development assistance (ODA) and other official flows from all donors in support of infrastructure in 2017 Total official flows commitments for aid for trade in 2017

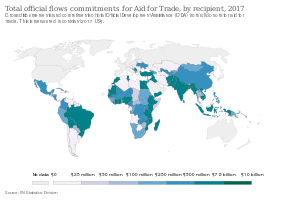

Total official flows commitments for aid for trade in 2017 Total water and sanitation-related Official Development Assistance (ODA) disbursements that are included in the government budget in 2015

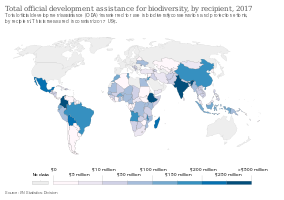

Total water and sanitation-related Official Development Assistance (ODA) disbursements that are included in the government budget in 2015 Total official development assistance (ODA) transferred for use in biodiversity conservation and protection efforts 2017

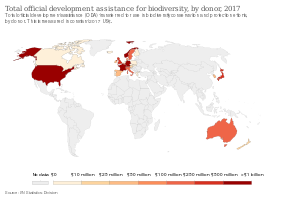

Total official development assistance (ODA) transferred for use in biodiversity conservation and protection efforts 2017 Total official development assistance for biodiversity, by donor in 2017

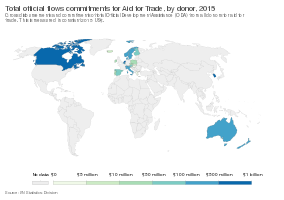

Total official development assistance for biodiversity, by donor in 2017 Total official flows commitments for Aid for Trade, by donor in 2015

Total official flows commitments for Aid for Trade, by donor in 2015

Effects of foreign aid on developing countries

Effect on the recipient country's development

Albert O. Hirschman’s exit-voice-loyalty (EVL) model can be used to understand how certain policy changes affect the growth of a nation and the change of bargaining power inside it. Clark et al.’s formalization of the model to politics shows the effect that developmental aid can have on the receiving country's development and highlights that the aid can potentially harm that country.

Hirschman’s EVL model is based on the foundation that “under any economic, social, or political system, individuals, business firms, and organizations, in general, are subject to lapses from efficient, rational, law-abiding, virtuous, or otherwise functional behavior”. The customer who is affected by the lapse in the system (a fall in the quality of a product they are consuming) has two ways to answer to this- “exit” or “voice”. If the individual chooses the former, they simply stop buying the product and inflict a revenue drop that forces the firm to either correct their mistake or cease to exist. If the individual chooses the “voice” option, then they will express their dissatisfaction to either the firm or something that has authority over it. This will force the firm to fix their lapse, but it will not suffer a decline in revenue. Lastly, Hirschman introduces the “loyalty” option, which occurs when the consumer cannot “exit” and the firm does not care about the effect that “voice” will have on their revenue, and the consumers who chose it continues to consume the lapsed good.

Clark et al.’s paper takes Hirschman's EVL model and applies it to political developments inside a nation.[26] When a government changes a policy that now has a negative effect on the welfare of some citizens, or is already being unresponsive to a deleterious situation, the citizens have the same 3 choices of response as before. Here, “exit” can take the form of citizens leaving the country The Art of Not Being Governed and hence depriving the state of their taxes or simply rearranging their capital and goods so they are not taxed by the government, as seen with British merchants threatening to move capital to the Netherlands if not given representation after the Glorious Revolution. “Voice” takes the form of non-violent civil disobedience, as seen with Gandhi's Salt March and the Black Lives Matter protests in Ferguson, a violent demonstration, as seen with Luddite breaking weaving machinery to protest the lack of protectionist policies by the English government, or even “everyday resistance” where small, non-cooperation and false create high costs for the state. “Loyalty” entails that the citizens simply accept the situation and continue their lives before.

How foreign aid enters this equation in weak states is by changing the citizens’ power of “voice” and “exit” and weakening the state's dependence on their citizens and hence becoming less responsive to their needs. If the state receives international aid, it is less dependent on the tax revenue that it collects from its constituents. A higher level of fiscal independence on the part of the state decreases the bargaining power of the citizens. The government is threatened less by the citizens’ “exit” option, and less hurt if it is implemented, hence this takes away a credible threat to use at the negotiation table in order for the citizens to request improvement to their current condition. At the same time, the lack of dependence for revenue decreases the “voice” action of the citizen by weakening the effect a violent demonstration or everyday resistance has on impacting the state's decision-making.

As long as the government of a nation receiving international aid knows that it will keep receiving it, and there will be no repercussion on the side of the donors for failing to address its constituents’ issues, it stays optimal for that government to keep ignoring the weakened demands of its citizens. With weakened bargaining power and a less responsive state, there can be no bargaining between citizen and state that will, in the long, run lead to economic and/or development within the nation. Although international has done far-reaching things with respect to increasing access to improved medical care, improving education, and decreasing poverty and hunger, only in 1997 did the World Bank began to rethink its aid policy structure and begin using parts of it specifically for building up the state capability of the aid-receiving nations . Even more recently, the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a US-based aid agency, started working with developing nation to provide them with strictly development aid as they set and implement goals for national development.

Effects of foreign aid in Africa.

While most economists like Jeffery Sachs hold the view of aid as the driver for economic growth and development, others argue that aid has rather led to increasing poverty and decreasing economic growth of poor countries.[27] Economists like Dambisa Moyo argue that aid does not lead to development, but rather creates problems including corruption, dependency, limitations on exports and dutch disease, which negatively affect the economic growth and development of most African countries and other poor countries across the globe.[27][28] However, economist Jeffery Sachs recognizes that policy members should be held accountable for understanding the geographic effects on poverty.[29] Sachs argues that in order for foreign aid to be successful, policy makers should "pay more attention to the developmental barriers associated with geography- specifically, poor health low agricultural productivity, and high transportation costs". The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund are two organizations that Sachs argues are currently instrumental in advising and directing foreign aid; however, he argues that these two organizations focus too much on "institutional reforms". Foreign aid is especially multifaceted in countries within Sub-Saharan Africa due to geographic barriers. Most macro foreign aid efforts fail to recognize these issues and, as Sachs argues, cause insufficient international aid and policy improvement. Sachs argues that unless foreign aid provides mechanisms that overcome geographic barriers, pandemics such as HIV and AIDS that cause traumatic casualties within regions such as Sub-Saharan Africa will continue to care millions of fatalities.

For aid to be effective and beneficial to economic development, there must be some support systems or ‘traction’ that, will enable foreign aid to spur economic growth.[30] Research has also shown that Aid actually damages economic growth and development before ‘traction’ is attained.[30]

Death of local industries

Foreign aid kills local industries in developing countries.[31] Foreign aid in the form of food aid that is given to poor countries or underdeveloped countries is responsible for the death of local farm industries in poor countries.[31] Local farmers end up going out of business because they cannot compete with the abundance of cheap imported aid food, that is brought into poor countries as a response to humanitarian crisis and natural disasters.[32] Large inflows of money that come into developing countries, from the developed world, in a foreign aid, increases the price of locally produced goods and products.[28] Due to their high prices, export of local goods reduces.[28] As a result, local industries and producers are forced to go out of business.

Neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is where a state is “in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside”.[33] The political and economic affairs of a state under neocolonialism, is directly controlled by external powers and nations from the Global North, who offer aid or assistance to countries in the Global South or developing countries.[33] Neocolonialism is the new face of colonialism, which is made possible by foreign aid.[34] [35]Donor countries offer foreign aid to poor countries while bargaining for economic influence of the poor or receiving countries, and policy standards that allow donor countries to control economic systems of poor countries, for the benefit of the donor countries.[36]

Foreign aid creates a system of dependency where developing or poor countries become heavily dependent on western or developed countries for economic growth and development.[37] As less developed countries become dependent on developed countries, the poor countries are easily exploited by the developed countries such that the developed world are able to directly control the economic activities of poor countries.[38]

Aid dependency

Aid dependence is defined as the "situation in which a country cannot perform many of the core functions of government, such as operations and maintenance, or the delivery of basic public services, without foreign aid funding and expertise".[39] Aid has made many African countries and other poor regions incapable of achieving economic growth and development without foreign assistance. Most African economies have become dependent on aid and this is because foreign aid has become a significant norm of systems of international relations between high and low income countries across the globe.[39]

Foreign aid makes African countries dependent on aid because it is regarded by policy makers as regular income, thus they do not have any incentive to make policies and decisions that will enable their countries to independently finance their economic growth and development.[27] Additionally, aid does not incentivize the government to tax citizens, due to the constant inflow of foreign aid, and as a result, the citizens do not have any obligation to demand the provision of goods and services geared towards development.[27]

Corruption

While development aid is an important source of investment for poor and often insecure societies, aid's complexity and the ever-expanding budgets leave it vulnerable to corruption, yet discussing it remains difficult as for many it is a taboo subject.[40]

Foreign aid encourages rent-seeking, which is when government officials and leaders, use their position and authority to increase their personal wealth without creating additional wealth, at the expense of the citizens.[27] Most African leaders and official, are able to amass huge sums of personal wealth for themselves from the foreign aid received - they enrich themselves and do not use the aid provided for its intended purpose.[27]

Corruption is very hard to quantify as it is often hard to differentiate it from other problems, such as wastage, mismanagement and inefficiency, to illustrate the point, over $8.75 billion was lost to waste, fraud, abuse and mismanagement in the Hurricane Katrina relief effort.[40] Non-governmental organizations have in recent years made great efforts to increase participation, accountability and transparency in dealing with aid, yet humanitarian assistance remains a poorly understood process to those meant to be receiving it—much greater investment needs to be made into researching and investing in relevant and effective accountability systems.[40]

However, there is little clear consensus on the trade-offs between speed and control, especially in emergency situations when the humanitarian imperative of saving lives and alleviating suffering may conflict with the time and resources required to minimise corruption risks.[40] Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute have highlighted the need to tackle corruption with, but not limited to, the following methods:[40]

- Resist the pressure to spend aid rapidly.

- Continue to invest in audit capacity, beyond simple paper trails;

- Establish and verify the effectiveness of complaints mechanisms, paying close attention to local power structures, security and cultural factors hindering complaints;

- Clearly explain the processes during the targeting and registration stages, highlighting points such as the fact that people should not make payments to be included, photocopy and read aloud any lists prepared by leaders or committees.

Positive effects of aid in Africa

Although aid has had some negative effects on the growth and development of most African countries, research shows that development aid, in particular, actually does have a strong and favorable effect on economic growth and development.[1] Development aid has a positive effect on growth because it may actually promote long term economic growth and development through promoting investments in infrastructure and human capital.[1] More evidence suggests that aid had indeed, had a positive effect on economic growth and development in most African countries. According to a study conducted among 36 sub-saharan African countries in 2013, 27 out of these 36 countries have experienced strong and favorable effects of aid on GDP and investments,[41] which is contrary to the believe that aid ineffective and does not lead to economic development in most African countries.

Research also shows that aid per capita supports economic growth for low income African countries such as Tanzania, Mozambique and Ethiopia, while aid per capita does not have a significant effect on the economic growth of middle income African countries such as Botswana and Morocco.[42] Aid is most beneficial to low income countries because such countries use aid received for to provide education and healthcare for citizens, which eventually improves economic growth in the long run.[42]

Effectiveness

Aid effectiveness is the degree to which development aid works, and is a subject of significant disagreement. Dissident economists such as Peter Bauer and Milton Friedman argued in the 1960s that aid is ineffective:[43]

... an excellent method for transferring money from poor people in rich countries to rich people in poor countries.

— Peter Bauer

In economics, there are two competing positions on aid. A view pro aid, supported by Jeffrey Sachs and the United Nations, which argues that foreign aid will give the big push to break the low-income poverty trap poorer countries are trapped in. From this perspective, aid serves to finance “the core inputs to development – teachers, health centers, roads, wells, medicine, to name a few...” (United Nations 2004).[44] And a view that is skeptic about the impacts of aid, supported by William Easterly, that points out that aid has not proven to work after 40 years of large investments in Africa.[44]

American political scientist and professor Nicolas van de Walle has also argued that despite more than two decades of donor-supported reform in Africa, the continent continues to be plagued by economic crises due to the combination of state generated factors and to the counter productivity of international development aid to Africa. Van de Walle first attributes the failure to implement economic policy reform to factors within the African state:

- Neopatrimonial tendencies of state elites that serve to preserve and centralize power, maintain limited access orders, and create political obstacles to reform.

- Ideological obstacles that have been biased by two decades of failed economic policy reform and in turn, create a hostile environment for reform.

- Low state capacity that reinforces and that in turn, is reinforced by the neopatrimonial tendencies of the state.

Van de Walle later argues that these state generated factors that have obstructed the effective implementation of economic policy reform are further exacerbated by foreign aid. Aid, therefore, makes policy reform less likely, rather than more likely. Van de Walle posits that international aid has sustained economic stagnation in Africa by:

- Pacifying Africa's neopatrimonial tendencies, thereby lessening the incentives for state elites to undertake reform and preserving the status quo.

- Sustaining poorly managed bureaucratic structures and policies that would be otherwise rectified by market forces.

- Allowing state capacities to deteriorate through externalizing many state functions and responsibilities.

In order for aid to be productive and for economic policy reform to be successfully implemented in Africa, the relationship between donors and governments must change. Van de Walle argues that aid must be made more conditional and selective to incentivize states to take on reform and to generate the much needed accountability and capacity in African governments.[45]

Additionally, information asymmetries often hinder the appropriate allocation of aid; Blum et al. (2016) note that both South Sudan and Liberia struggle tremendously with paying employees and controlling the flow of money - South Sudan had a significant number of ghosts on its payroll, while Liberia's Civil Service Agency could not adequately pay civil servants because there was minimal communication from the Ministries of Health and Education regarding their respective payrolls.[46]

Many econometric studies in recent years have supported the view that development aid has no effect on the speed with which countries develop. Negative side effects of aid can include an unbalanced appreciation of the recipient's currency (known as Dutch Disease), increasing corruption, and adverse political effects such as postponements of necessary economic and democratic reforms.[47]

It has been argued that much government-to-government aid was ineffective because it was merely a way to support strategically important leaders (Alesino and Dollar, 2000). A good example of this is the former dictator of Zaire, Mobuto Sese Seko, who lost support from the West after the Cold War had ended. Mobuto, at the time of his death, had a sufficient personal fortune (particularly in Swiss banks) to pay off the entire external debt of Zaire.[47]

Besides some instances that only the president (and/or his close entourage) receives the money resulting from development aid, the money obtained is often badly spent as well. For example, in Chad, the Chad Export Project, an oil production project supported by the World Bank, was set up. The earnings of this project (6.5 million dollars per year and rising) were used to obtain arms. The government defended this purchase by stating that "development was not possible without safety". However, the Military of Chad is notorious for severe misconduct against the population (abuse, rape, claiming of supplies and cars) and did not even defend the population in distress (e.g. in the Darfur conflict). In 2008, the World Bank retreated from the project that thus increased environmental pollution and human suffering.[48]

Another criticism has been that Western countries often project their own needs and solutions onto other societies and cultures. In response, western help in some cases has become more 'endogenous', which means that needs as well as solutions are being devised in accordance with local cultures.[49] For example, sometimes projects are set up which wish to make several ethnic groups cooperate. While this is a noble goal, most of these projects fail because of this intent.[48]Additionally, although the goal in utility to provide a larger social benefit may be justified as worthy, a more ethically sourced incentive would be projects not looking for an opportunity to impose a social hierarchy through cooperation, but more-so for the sake of truly assisting recipients. The intent of cooperation is not necessarily a reason for failure, but the very nature of different aspirations towards defining virtues which exist in direct context with respective societies. In this way a disconnect may be perceived among those imposing their virtues onto ethnic groups interpreting them.

The Center for Global Development have published a review[50] essay of the existing literature studying the relationship between Aid and public institutions. In this review, they concluded that a large and sustained Aid can have a negative effect in the development of good public institutions in low income countries. They also mention some of the arguments exhibited in this article as possible mechanism for this negative effect, for instance, they considered the Dutch Disease, the discourage of revenue collections and the effect on the state capacity among others.

Furthermore, the effect of Aid on conflict intensity and onset have been proved to have different impacts in different countries and situations. For instance, for the case of Colombia Dube and Naidu (2015)[51] showed that Aid from the US seems to have been diverted to paramilitary groups, increasing political violence. Moreover, Nunn and Qian (2014)[52] have found that an increase in U.S. food aid increases conflict intensity; they claim that the main mechanism driving this result is predation of the aid by the rebel groups. In fact, they note that aid can have the unintentional consequence of actually improving rebel groups' ability to continue conflict, as vehicles and communications equipment usually accompany the aid that is stolen.[52] These tools improve the ability of rebel groups to organize and give them assets to trade for arms, possibly increasing the length of the fighting. Finally, Crost, Felter and Johnston (2014)[53] have showed that a development program in the Philippines have had the unintended effect of increasing conflict because of an strategic retaliation from the rebel group, on where they tried to prevent that the development program increases support to the government.

It has also been argued that help based on direct donation creates dependency and corruption, and has an adverse effect on local production. As a result, a shift has taken place towards aid based on activation of local assets and stimulation measures such as microcredit.

Aid has also been ineffective in young recipient countries in which ethnic tensions are strong: sometimes ethnic conflicts have prevented efficient delivery of aid.

In some cases, western surpluses that resulted from faulty agriculture- or other policies have been dumped in poor countries, thus wiping out local production and increasing dependency.

In several instances, loans that were considered irretrievable (for instance because funds had been embezzled by a dictator who has already died or disappeared), have been written off by donor countries, who subsequently booked this as development aid.

In many cases, Western governments placed orders with Western companies as a form of subsidizing them, and later shipped these goods to poor countries who often had no use for them. These projects are sometimes called 'white elephants'.

According to James Ferguson, these issues might be caused by deficient diagnostics of the development agencies. In his book The Anti-Politics Machine, Ferguson uses the example of the Thaba-Tseka project in Lesotho to illustrate how a bad diagnostic on the economic activity of the population and the desire to stay away from local politics, caused a livestock project to fail.[54]

According to Martijn Nitzsche, another problem is the way on how development projects are sometimes constructed and how they are maintained by the local population. Often, projects are made with technology that is hard to understand and too difficult to repair, resulting in unavoidable failure over time. Also, in some cases the local population is not very interested in seeing the project to succeed and may revert to disassembling it to retain valuable source materials. Finally, villagers do not always maintain a project as they believe the original development workers or others in the surroundings will repair it when it fails (which is not always so).[55]

A common criticism in recent years is that rich countries have put so many conditions on aid that it has reduced aid effectiveness. In the example of tied aid, donor countries often require the recipient to purchase goods and services from the donor, even if these are cheaper elsewhere. Other conditions include opening up the country to foreign investment, even if it might not be ready to do so.[56]

All of these problems have made that a very large part of the spend money on development aid is simply wasted uselessly. According to Gerbert van der Aa, for the Netherlands, only 33% of the development aid is successful, another 33% fails and of the remaining 33% the effect is unclear. This means that for example for the Netherlands, 1.33 to 2.66 billion is lost as it spends 4 billion in total of development aid (or 0,8% of the gross national product).[55]

For the Italian development aid for instance, we find that one of their successful projects (the Keita project) was constructed at the cost of 2/3 of 1 F-22 fighter jet (100 million $), and was able to reforest 1,876 square miles (4,900 km2) of broken, barren earth, hereby increasing the socio-economic wellbeing of the area.[57] However -like the Dutch development aid- again we find that, the Italian development aid too is still not performing up to standards.[58] This makes clear that there are great differences between the success of the projects and that budgetary follow-up may not be so strictly checked by independent third parties.

An excerpt from Thomas Dichter's recently published book Despite Good Intentions: Why Development Assistance to the Third World Has Failed reads: "This industry has become one in which the benefits of what is spent are increasingly in inverse proportion to the amount spent - a case of more gets you less. As donors are attracted on the basis of appeals emphasizing "product", results, and accountability...the tendency to engage in project-based, direct-action development becomes inevitable. Because funding for development is increasingly finite, this situation is very much a zero-sum game. What gets lost in the shuffle is the far more challenging long-term process of development."

Effectiveness of development aid can be argued to be uncoordinated and unsustainable. Development aid tends to be put towards specific diseases with high death rates and simple treatments, rather than funding health basics and infrastructure. Though a lot of NGO's and funding have come forth, little sustainable outcomes have been made. This is due to the fact that the money doesn't go towards developing a sustainable medical basis. Money is given to specific diseases to show short-term results, reflecting the donor's best interests rather than the citizens' necessities. It is evident that many development aid projects are not helping with basic and sustainable health care due to the generally high numbers of deaths due to preventable diseases. Development aid could do more justice if used to generate general public health with infrastructure and trained personnel rather than pin-pointing specific diseases and reaching for quick fixes.[59]

Research has shown that developed nations are more likely to give aid to nations who have the worst economic situations and policies (Burnside, C., Dollar, D., 2000). They give money to these nations so that they can become developed and begin to turn these policies around. It has also been found that aid relates to the population of a nation as well, and that the smaller a nation is, the more likely it is to receive funds from donor agencies. The harsh reality of this is that it is very unlikely that a developing nation with a lack of resources, policies, and good governance will be able to utilize incoming aid money in order to get on their feet and begin to turn the damaged economy around. It is more likely that a nation with good economic policies and good governance will be able to utilize aid money to help the country establish itself with an existing foundation and be able to rise from there with the help of the international community. But research shows that it is the low-income nations that will receive aid more so, and the better off a nation is, the less aid money it will be granted. On the other hand, Alesina and Dollar (2000) note that private foreign investment often responds positively to more substantive economic policy and better protections under the law.[20] There is increased private foreign investment in developing nations with these attributes, especially in the higher income ones, perhaps due to being larger and possibly more profitable markets.[20]

MIT based study

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Abhijit Banerjee and Ruimin He have undertaken a rigorous study of the relatively few independent evaluations of aid program successes and failures.[60] They suggest the following interventions are usually highly effective forms of aid in normal circumstances:

- subsidies given directly to families to be spent on children's education and health

- education vouchers for school uniforms and textbooks

- teaching selected illiterate adults to read and write

- deworming drugs and vitamin/nutritional supplements

- vaccination and HIV/AIDS prevention programs

- indoor sprays against malaria, anti-mosquito bed netting

- suitable fertilizers

- clean water supplies

UK Parliamentary study

An inquiry into aid effectiveness by the UK All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) for Debt, Aid and Trade featured evidence from Rosalind Eyben, a Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies. Her evidence to the inquiry stated that effective aid requires as much investing in relationships as in managing money. It suggests Development organisations need to change the way they work to manage better the multiple partnerships that the Accra Agenda for Action recognises is at the core of the aid business. In relation to this specific inquiry, Dr Eyben outlined the following points:[61]

- Achieving impact requires investing in relationships, development organisations need to support their staff to do this. At the moment, the opposite is happening.

- In multiple sets of relationships there will be different ideas about what is success and how to achieve it and this should be reflected in methodologies for defining and assessing the impact of aid.

- Helpful procedural harmonisation should not mean assuming there is only a single diagnosis and solution to any complex problem.

- In addition to measuring results, donors need to assess the quality of relations at project/programme, country and international levels against indicators agreed with partners.

- Decisions on aid need to be made on a case by case basis on the advice of well-informed country offices.

- Accountable states depend on empowered citizens

- Development organisations also need to be more accountable to UK citizens through encouraging conversations as to the real challenges and limitations of aid. (Point made in relation to UK as evidence for UK parliamentary inquiry)

The views above are of Eyben. There were many other submissions to the All Party Parliamentary Group for Debt, Aid and Trade's inquiry into Aid Effectiveness. The final report gathered a vast amount of information from a wide range of sources to ensure a balanced perspective on the issues of aid effectiveness. The All Party Parliamentary Group for Debt, Aid and Trade's inquiry into Aid Effectiveness can be found online and the submissions of other contributors are available upon request.

Types of aid

Private aid

Development charities make up a vast web of non-governmental organizations, religious ministries, foundations, business donations and college scholarships devoted to development aid. Estimates vary, but private aid is at least as large as ODA within the United States, at $16 billion in 2003. World figures for private aid are not well tracked, so cross-country comparisons are not easily possible, though it does seem that per person, some other countries may give more, or have similar incentives that the United States has for its citizens to encourage giving.[62]

Aid for gender equality

Starting at the beginning of the UN Decade for Women in 1975, the women in development (WID) approach to international development began to inform the provision of development aid.[63] Some academics criticized the WID approach for relying on integrating women into existing development aid paradigms instead of promulgating specific aid to encourage gender equality.[63] The gender and development approach was created in response, to discuss international development in terms of societal gender roles and to challenge these gender roles within development policy.[64] Women in Development predominated as the approach to gender in development aid through the 1980s.[65] Starting in the early 1990s Gender and Development's influence encouraged gender mainstreaming within international development aid.[66]

The World Conference on Women, 1995 promulgated gender mainstreaming on all policy levels for the United Nations.[67][68] Gender Mainstreaming has been adopted by nearly all units of the UN with the UN Economic and Social Council adopting a definition which indicated an “ultimate goal... to achieve gender equality.”[69] The UN included promoting gender equality and empowering women as one of eight Millennium Development Goals for developing countries.

The EU integrated women in development thinking into its aid policy starting with the Lomé Convention in 1984.[70] In 1992 the EU's Latin American and Asian development policy first clearly said that development programs should not have detrimental effects on the position and role of women.[71] Since then the EU has continued the policy of including gender equality within development aid and programs.[64] Within the EU gender equality is increasingly introduced in programmatic ways.[72] The bulk of the EU's aid for gender equality seeks to increase women's access to education, employment and reproductive health services. However, some areas of gender inequality are targeted according to region, such as land reform and counteracting the effects of gangs on women in Latin America.[72]

USAID first established a women in development office in 1974 and in 1996 promulgated its Gender Plan of Action to further integrate gender equality into aid programs.[73] In 2012 USAID released a Gender Equality and Female Empowerment Policy to guide its aid programs in making gender equality a central goal.[73] USAID saw increased solicitations from aid programs which integrated gender equality from 1995-2010.[73] As part of their increased aid provision, USAID developed PROMOTE to target gender inequality in Afghanistan with $216 million in aid coming directly from USAID and $200 million coming from other donors.[73][74]

Many NGOs have also incorporated gender equality into their programs. Within the Netherlands, NGOs including Oxfam Netherlands Organization for Development Assistance, the Humanist Institute for Cooperation with Developing Countries, Interchurch Organization for Development Cooperation, and Catholic Organization for Relief and Development Aid have included certain targets for their aid programs with regards to gender equality.[75] NGOs which receive aid dollars through the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs or which partner with the Norwegian government on aid projects must “demonstrate that they take women and gender equality seriously.”[76] In response to this requirement organizations like the Norwegian Christian charity Digni have initiated projects which target gender equality.[76]

Private foundations provide the majority of their gender related aid to health programs and have relatively neglected other areas of gender inequality.[77] Foundations, such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, have partnered with governmental aid organizations to provide funds for gender equality, but increasingly aid is provided through partnerships with local organizations and NGOS.[77] Corporations also participate in providing gender equality aid through their Corporate Social Responsibility programs. Nike helped to create the Girl Effect to provide aid programs targeted towards adolescent girls.[78] Using publicly available data Una Osili an economist at the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis found that between 2000-10 $1.15 billion in private aid grants over $1 million from the United States targeted gender equality.[79]

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development provides detailed analysis of the extent of aid for gender equality. OECD member countries tag their aid programs with gender markers when a program is designed to advanced gender equality.[80] In 2014 OECD member nations committed almost $37 billion to aid for gender equality, with over $7 billion of that committed to programs where gender equality is a principal programmatic goal.[81]

Effectiveness of aid for gender equality

Three main measures of gender inequality are used in calculating gender equality and testing programs for the purposes of development aid. In the 1995 Human Development Report the United Nations Development Program introduced the Gender Development Index and Gender Empowerment Measure.[82] The Gender Empowerment Measure is calculated based on three measures, proportion of women in national parliaments, percentage of women in economic decision making positions and female share of income. The Gender Development Index uses the Human Development Index and corrects its results in life expectancy, income, and education for gender imbalances.[82] Due to criticisms of these two indexes the United Nations Development Program in its 2010 Human Development Report introduced the Gender Inequality Index. The Gender Inequality Index uses more metrics and attempts to show the losses from gender inequality.[82]

Even with these indexes, Ranjula Swain of the Stockholm School of Economics and Supriya Garikipati of the University of Liverpool found that, compared to the effectiveness of health, economic, and education targeted aid, foreign aid for gender equality remains understudied.[82] Swain and Garikipati found in an analysis of Gender Equality Aid that on a country and region-wide level gender equality aid was not significant in its effect. Swain and Garikipati blame this on the relative lack of aid with gender equality as a primary motivation.[83]

In 2005, the Interagency Gender Working Group of the World Health Organization released the “So What? Report” on the effectiveness of gender mainstreaming in NGO reproductive health programs. The report found these programs effective, but had trouble finding clear gender outcomes because most programs did not measure this data.[84] When gender outcomes were measured, the report found positive programmatic effects, but the report did not look at whether these results were from increased access to services or increasing gender equality.[84][85]

Even when gender equality is identified as a goal of aid, other factors will often be the primary focus of the aid.[83] In some instances the nature of aid's gender equality component can fail to be implemented at the level of individual projects when it is a secondary aspect of a project.[86] Gender equality is often put forward as a policy goal for the organization but program staff have differing commitment and training with regards to this goal.[87] When gender equality is a secondary aspect, development aid which has funds required to impact gender equality can be used to meet quotas of women receiving aid, without effecting the changes in gender roles that Gender Mainstreaming was meant to promote.[87] Programs can also fail to provide lasting effects, with local organizations removing gender equality aspects of programs after international aid dollars are no longer funding them.[85]

Robert C. Jones of McGill University and Liam Swiss of Memorial University argue that women leaders of governmental aid organizations and NGOs are more effective at Gender Mainstreaming than their male counterparts.[88] They found in a literature review that NGOs headed by women were more likely to have Gender Mainstreaming programs and that women were often the heads of Gender Mainstreaming programs within organizations.[89] By breaking down gender equality programs into two categories, gender mainstreamed programs and gender-focused programs which do not mainstream gender, Jones and Swiss found that female leaders of governmental aid organizations provided more financial support to gender mainstreamed programs and slightly more support to gender aware programs overall.[90]

Criticism of aid for gender equality

Petra Debusscher of Ghent University has criticized EU aid agencies for following an “integrationist approach” to gender mainstreaming, where gender mainstreaming is used to achieve existing policy goals, as opposed to a “transformative approach” which seeks to change policy priorities and programs fundamentally to achieve gender equality.[70] She finds that this approach more closely follows a Women in Development model than a Gender and Development one. Debussher criticized the EU's development policy in Latin America for focusing too much attention on gender inequality as a problem to be solved for women.[91] She found that the language used represented more of a Woman in Development approach than a Gender and Development Approach.[92] She notes that men's role in domestic violence is insufficiently brought forward, with program and policy instead targeting removing women from victimhood.[91] Rather than discussing the role of men and women relative to each other, women are discussed as needing to “catch up with an implicit male norm.”[91] Debussher also criticized EU's development aid to Southern Africa as too narrow in its scope and too reliant on integrating women and gender into existing aid paradigms.[93] Debusscher notes that women's organizations in the region are often concerned with different social constructions of gender, as opposed to the economic growth structure favored by the EU.[94] For EU development aid to Europe and surrounding countries, Debsusscher argued that programs to encourage education of women were designed primarily to encourage overall economic growth, not to target familial and social inequalities.[95]

Some criticism of gender equality development aid discusses a lack of voices of women's organizations in developing aid programs. Debusscher argued that feminist and women's organizations were not represented enough in EU aid.[96] and that while feminist and women's organizations were represented in implementing policy programs they were not sufficiently involved in their development in EU aid to Southern Africa.[93] Similarly, Jones and Swiss argue that more women need to be in leadership positions of aid organizations and that these organizations need to be “demasculinized” in order to better gender mainstream.[97] T.K.S. Ravindran and A. Kelkar-Khambete criticized the Millennium Development Goals for insufficiently integrating gender into all development goals, instead creating its own development goal, as limiting the level of aid provided to promote gender equality.[98]

Remittances

It is doubtful whether remittances, money sent home by foreign workers, ought to be considered a form of development aid. However, they appear to constitute a large proportion of the flows of money between developed and developing countries, although the exact amounts are uncertain because remittances are poorly tracked. World Bank estimates for remittance flows to developing countries in 2004 totalled $122 billion; however, this number is expected to change upwards in the next few years as the formulas used to calculate remittance flows are modified. The exact nature and effects of remittance money remain contested,[99] however in at least 36 of the 153 countries tracked remittance sums were second only to FDI and outnumbered both public and private aid donations.[100]

The International Monetary Fund has reported that private remittances may have a negative impact on economic growth, as they are often used for private consumption of individuals and families, not for economic development of the region or country.[101]

National development aid programs

- Australian Agency for International Development

- China foreign aid

- Department for International Development (United Kingdom)

- International economic cooperation policy of Japan

- Saudi foreign assistance

- Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency

- United States foreign aid

- United Arab Emirates foreign aid

See also

- International Development

- Development economics

- Global South Development Magazine

Effectiveness and anti-corruption measures:

General:

Tools and Stories:

References

- "Development Aid and Economic Growth: A Positive Long-Run Relation" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- WHO glossary of terms, "Development Cooperation" Accessed 25 January 2008

- OECD Stats. Portal >> Extracts >> Development >> Other >> DAC1 Official and Private Flows. Retrieved April 2009.

- OECD, DAC1 Official and Private Flows (op. cit.). The calculation is Net Private Grants / ODA.

- Joseph Hodge, Gerald Hodl, & Martin Kopf (edi) Developing Africa: Concepts and Practices in Twentieth-Century Colonialism, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2014, p.12.

- Bekeh Utietiang, Planning Development: International Experts, Agricultural Policy, and the Modernization of Nigeria, 1945-1967 (Ph.D Thesis), West Virginia University, Morgantown, 2014, p. 38.

- Stephen Constantine, The Making of British Colonial Development Policy, 1914-1940, London: Frank Cass, 1984, p.183.

- Kanbur, Ravi (2006), "The economics of international aid", in Kolm, Serge-Christophe; Ythier, Jean Mercier (eds.), Handbook of the economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity: foundations, volume 1, Amsterdam London: Elsevier, ISBN 9780444506979.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fraser, Cary (1996). "The Twilight of Colonial Rule in the British West Indies: Nationalist Assertion vs. Imperial Hubris in the 1930s". Journal of Caribbean History. 30 (1/2): 2.

- Basdeo, Sahadeo (1983). "Walter Citrine and the British Caribbean Worker's Movement during the Commission Hearing". Journal of Caribbean History. 18 (2): 46.

- Thomas. p. 229. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Singh, Kelvin (1994). Race and Class Struggles in a Colonial State. Calgary: University of Calgary Press. p. 186. ISBN 9781895176438.

- Thomas, Roy Darrow, ed. (1987). The Trinidad Labour Riots of 1937. St. Augustine: University of West Indies Press. p. 267.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Parker. p. 23. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Thomas. p. 283. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Bolland. The Politics of Labour in the British Caribbean. p. 383.

- "USAID: USAID History". Usaid.gov. Archived from the original on 2011-10-09. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- Transcript of the speech

- Faye, Michael; Niehaus, Paul (2012-12-01). "Political Aid Cycles" (PDF). American Economic Review. 102 (7): 3516–3530. doi:10.1257/aer.102.7.3516. ISSN 0002-8282. S2CID 154408829.

- Alesina, Alberto; Dollar, David (2000). "Who Gives Foreign Aid to Whom and Why?". Journal of Economic Growth. 5 (1): 33–63. doi:10.1023/A:1009874203400. JSTOR 40216022.

- OECD The Typing of Aid

- "Aid to developing countries rebounds in 2013 to reach an all-time high". OECD. 8 April 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Net official development assistance and official aid received (current US$)". World Development Indicators. World Bank. Retrieved 15 March 2017.

- "Development and cooperation". European Union. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Hunt, Michael (2014). The World Transformed 1945 to the Present. New York: New York. pp. 516–517. ISBN 9780199371020.

- Moyo, D. (2009). Dead aid: Why aid is not working and how there is a better way for Africa. Macmillan.

- "Why Foreign Aid Is Hurting Africa" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- Sachs, Jeffery. "The Geography of Poverty and Weather "The Scientific American"".

- Rahnama, M. & Fawaz, F. & Gittings, K. (2017). The effects of foreign aid on economic growth in developing countries. The Journal of Developing Areas 51(3), 153-171. Tennessee State University College of Business.

- Bandow, Doug. "Foreign Aid, Or Foreign Hindrance". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- NW, 1310 L. Street; Washington, 7th Floor; Fax: 202-331-0640, DC 20005 Phone: 202-331-1010 (2007-08-16). "Foreign Aid Kills". Competitive Enterprise Institute. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- Nkrumah, K. (1966). Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism. 1965. Introduction. New York: International.

- "Neocolonialism: The New Face Of Imperialism (And Why It Should've Gone For A Nicer One)". Affinity Magazine. 2016-11-27. Retrieved 2019-04-05.

- Markovits, D., Strange, A., & Tingley, D. (2017). Foreign Aid and the Status Quo: Evidence from Pre-Marshall Plan Aid. p.5 Harvard School of Government.

- Asongu, Simplice A.; Nwachukwu, Jacinta C. (2016-01-02). "Foreign aid and governance in Africa" (PDF). International Review of Applied Economics. 30 (1): 69–88. doi:10.1080/02692171.2015.1074164. ISSN 0269-2171.

- Vengroff, R. (1975). Neo-colonialism and policy outputs in Africa. Comparative Political Studies, 8(2), 234-250.

- "Is Foreign Aid a facilitator of Neo-Colonialism in Africa?".

- "Aid Dependenceand Governance" (PDF). Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- Sarah Bailey (2008) Need and greed: corruption risks, perceptions and prevention in humanitarian assistance Overseas Development Institute

- Juselius, Katarina; Møller, Niels Framroze; Tarp, Finn (2013). "The Long-Run Impact of Foreign Aid in 36 African Countries: Insights from Multivariate Time Series Analysis*: Long-run impact of foreign aid in African countries". Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics. 76 (2): 153–184. doi:10.1111/obes.12012. hdl:10.1111/obes.12012.

- Lee, Jin-Sang; Alemu, Aye Mengistu (2015-11-27). "Foreign aid on economic growth in Africa: A comparison of low and middle-income countries". South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences. 18 (4): 449–462. doi:10.4102/sajems.v18i4.737. ISSN 2222-3436.

- "The sad loss of Lord Bauer".

- Qian, Nancy (2015-08-03). "Making Progress on Foreign Aid". Annual Review of Economics. 7: 277–308. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115553.

- Van de Walle, Nicolas (2004). "Economic Reform: Patterns and Constraints". In Gyimah-Boadi, Emmanuel (ed.). Democratic Reform in Africa: The Quality of Progress. 1800 30th Street, Boulder, Colorado 80301: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc. pp. 29–63. ISBN 1588262464.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Blum, Jurgen, Fotini Christia, and Daniel Rogger. 2016. “Public Service Reform in Post-Conflict Societies.” World Bank: Fragile and Conflict State Impact Evaluation Research Program paper.

- Aid Effectiveness and Governance: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly Archived 2009-10-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Tsjaad by Dorrit van Dalen

- The Future of The Anti-Corruption Movement Archived 2009-04-09 at the Wayback Machine, Nathaniel Heller, Global Integrity

- Moss, Petterson and van de Walle (January 2006). "An Aid-Institutions Paradox? A Review Essay on Aid Dependency and State Building in Sub-Saharan Africa". Center for Global Development. Working Paper Number 74.

- Dube and Naidu (January 6, 2015). "Bases, Bullets, and Ballots: The Effect of US Military Aid on Political Conflict in Colombia". The Journal of Politics. 77 (1): 249–267. doi:10.1086/679021.

- Nunn and Qian (June 2014). "US Food Aid and Civil Conflict". American Economic Review. 1630-1666 (6): 1630–1666. doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1630. JSTOR 42920861.

- Crost, Felter and Johnston (June 2014). "Aid Under Fire: Development Projects and Civil Conflict". American Economic Review. 1833–1856 (6): 1833–1856. doi:10.1257/aer.104.6.1833.

- Ferguson, James (1994). "The anti-politics machine: 'development' and bureaucratic power in Lesotho" (PDF). The Ecologist. 24 (5). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-29. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- Kijk magazine; oktober 2008, Gestrand Ontwikkelingswerk

- "US and Foreign Aid Assistance". Global Issues. 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- Keita project increasing socio-economic wellbeing Archived 2012-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "Italian aid not up to standard overall". Archived from the original on 2008-02-16. Retrieved 2009-05-23.

- Garrett, Laurie (2007). "The Challenge of Global Health". Foreign Affairs. 86 (1): 14–38.

- "Making aid work" (PDF). 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-10. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- 'Putting Relationships First for Aid Effectiveness' Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine Evidence Submission to the APPG Inquiry on Aid Effectiveness, Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

- "Ranking The Rich Based On Commitment To Development". globalissues.org. Retrieved 2008-03-06.

- Charlesworth, Hillary. "Not Waving But Drowning Gender Mainstreaming and Human Rights in the United nations". Harvard Human Rights Journal. 18: 2.

- Debusscher, Petra. "Gender Mainstreaming in European Union Development Policy Towards Latin America: Transforming Gender Relations or Confirming Hierarchies?". Latin American Perspectives. 39: 182.

- Jones, Robert; Swiss, Liam (September 2014). "Gendered Leadership: The Effects of Female Development Agency Leaders on Foreign Aid Spending". Sociological Forum. 29 (3): 574. doi:10.1111/socf.12104.

- "Does Foreign Aid Improve Gender Performance of Recipient Countries? Results from Structural Equation Analysis". Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- Charlesworth, Hilary. "Not Waving But Drowing Gender Mainstreaming and Human Rights in the United Nations". Harvard Human Rights Journal. 18: 3.

- "Report of the Fourth World Conference on Women".

- Charlesworth, Hillary. "Not Waving But Drowning Gender Mainstreaming and Human Rights in the United nations". Harvard Human Rights Journal. 18: 4-5.

- Debusscher, Petra; Hulse, Merran (2014). "Including Women's Voices? Gender Mainstreaming in EU and SADC Development Strategies for Southern Africa". Journal of Southern African Studies. 40 (3): 561–562. doi:10.1080/03057070.2014.909255. S2CID 145495201.

- Debusscher, Petra. "Gender Mainstreaming in European Union Development Policy Towards Latin America: Transforming Gender Relations or Confirming Hierarchies?". Latin American Perspectives. 39: 181. doi:10.1177/0094582x12458423.

- Debusscher, Petra. "Gender Mainstreaming in European Union Development Policy Towards Latin America: Transforming Gender Relations or Confirming Hierarchies?". Latin American Perspectives. 39: 187–189. doi:10.1177/0094582x12458423.

- "Gender Equality and Female Empowerment Policy" (PDF). USAID.

- "Promote". USAID. Retrieved 2017-05-27.

- Van Eerdewijk, Anouka (2014). "The Micropolitics of Evaporation: Gender Mainstreaming Instruments in Practice". Journal of International Development. 26 (3): 348–349. doi:10.1002/jid.2951.

- Østebo, Marit; Haukanes, Haldis; Blystad, Astrid. "Strong State Policies on Gender and Aid: Threats and Opportunities for Norwegian Faith-Based Organisations". Forum for Development Studies. 40 (2): 194.

- Okonkwo, Osili, Una (2013). Non-traditional aid and gender equity evidence from million dollar donations. WIDER. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9789292306533. OCLC 931344632.

- Okonkwo, Osili, Una (2013). Non-traditional aid and gender equity evidence from million dollar donations. WIDER. p. 6. ISBN 9789292306533. OCLC 931344632.

- Okonkwo, Osili, Una (2013). Non-traditional aid and gender equity evidence from million dollar donations. WIDER. p. 8. ISBN 9789292306533. OCLC 931344632.

- Okonkwo, Osili, Una (2013). Non-traditional aid and gender equity evidence from million dollar donations. WIDER. p. 3. ISBN 9789292306533. OCLC 931344632.

- "Gender-related aid data at a glance". OECD.

- "Does Foreign Aid Improve Gender Performance of Recipient Countries? Results from Structural Equation Analysis". Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- "Does Foreign Aid Improve Gender Performance of Recipient Countries? Results from Structural Equation Analysis". Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- "A Summary of the "So What?" Report" (PDF). WHO.

- Ravindran, TKS; Kelkar-Khambete, A. (2008). "Gender Mainstreaming in Health: Looking Back, Looking Forward". Global Public Health. 3: 127–129. doi:10.1080/17441690801900761. PMID 19288347.

- Charlesworth, Hilary. "Not Waving But Drowing Gender Mainstreaming and Human Rights in the United Nations". Harvard Human Rights Journal. 18: 12.

- Van Eerdewijk, Anouka. "The Micropolitics of Evaporation: Gender Mainstreaming Instruments in Practice". Journal of International Development. 26: 353.

- Smith, Robert; Swiss, Liam. "Gendered Leadership: The Effects of Female Development Agency Leaders on Foreign Aid Spending". Sociological Forum. 29 (3).

- Jones, Robert; Swiss, Liam (September 2014). "Gendered Leadership: The Effects of Female Development Agency Leaders on Foreign Aid Spending". Sociological Forum. 29 (3): 578.

- Jones, Robert; Swiss, Liam (September 2014). "Gendered Leadership: The Effects of Female Development Agency Leaders on Foreign Aid Spending". Sociological Forum. 29 (3): 582-583.

- Debusscher, Petra. "Gender Mainstreaming in European Union Development Policy Towards Latin America: Transforming Gender Relations or Confirming Hierarchies?". Latin American Perspectives. 39: 190.

- Debusscher, Petra. "Gender Mainstreaming in European Union Development Policy Towards Latin America: Transforming Gender Relations or Confirming Hierarchies?". Latin American Perspectives. 39: 192-194.

- Debusscher, Petra; Hulse, Merran. "Including Women's Voices? Gender Mainstreaming in EU and SADC Development Strategies for Southern Africa". Journal of Southern African Studies. 40 (3): 571-572.

- Debusscher, Petra; Hulse, Merran. "Including Women's Voices? Gender Mainstreaming in EU and SADC Development Strategies for Southern Africa". Journal of Southern African Studies. 40 (3): 566-567.

- Debusscher, Petra (2012-10-01). "Mainstreaming Gender in European Union Development Policy in the European Neighborhood". Journal of Women, Politics & Policy. 33 (4): 333. doi:10.1080/1554477X.2012.722427. ISSN 1554-477X. S2CID 143826318.

- Debusscher, Petra. "Gender Mainstreaming in European Union Development Policy Towards Latin America: Transforming Gender Relations or Confirming Hierarchies?". Latin American Perspectives. 39: 191-192.

- Jones, Robert; Swiss, Liam (September 2014). "Gendered Leadership: The Effects of Female Development Agency Leaders on Foreign Aid Spending". Sociological Forum. 29 (3): 583-584.

- Ravindran, TKS; Kelkar-Khambete, A. "Gender Mainstreaming in Health: Looking Back, Looking Forward". Global Public Health. 3: 139.

- Are Immigrant Remittance Flows a Source of Capital for Development? - WP/03/189

- Approaches to a Regulatory Framework for Formal and Informal Remittance Systems: Experiences and Lessons, February 17, 2005

- Are Immigrant Remittance Flows a Source of Capital for Development

Further reading

- Georgeou, Nichole, Neoliberalism, Development, and Aid Volunteering, New York: Routledge, 2012. ISBN 9780415809153.

- Gilbert Rist, The History of Development: From Western Origins to Global Faith, Zed Books, New Exp. Edition, 2002, ISBN 1-84277-181-7

- Perspectives on European Development Co-operation by O. Stokke

- European development cooperation and the poor by A. Cox, J. Healy and T. Voipio ISBN 0-333-74476-4

- Rethinking Poverty: Comparative perspectives from below. by W. Pansters, G. Dijkstra, E. Snel ISBN 90-232-3598-3

- European aid for poverty reduction in Tanzania by T. Voipio London, Overseas Development Institute, ISBN 0-85003-415-9

- The Bottom Billion: Why the Poorest Countries are Failing and What Can Be Done About It by Paul Collier

- How Do We Help? The Free Market in Development Aid by Patrick Develtere, 2012, Leuven University Press, ISBN 978-90-5867-902-4

External links

- Open Aid Register

- IATI search engine (Beta). Find any development aid activity around the world. Using the IATI registry as access point.

- Aid and Development at Curlie

- AidData: Tracking Development Finance

- Open Aid Data Provides detailed developing aid finance data from around the world.

- Center for International Development at Harvard University

- The Centre for Aid and Public Expenditure, Overseas Development Institute

- Millions Saved A compilation of case studies of successful foreign assistance by the Center for Global Development.

- German Development Institute - the German think tank of development aid

- Work on Development Aid by the Institute of Development Studies (IDS)

- Articles

- Abhijit Baerjee "Making Aid Work". Boston Review, March/April 2007.

- Failed Expectations, Or What Is Behind the Marshall Plan for Post-Socialist Reconstruction, by Tanya Narozhna

- Håkan Malmqvist (February 2000), "Development Aid, Humanitarian Assistance and Emergency Relief", Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Monograph No 46, Sweden

- Andrew Rogerson with Adrian Hewitt and David Waldenberg (2004), "The International Aid System 2005–2010 Forces For and Against Change", Overseas Development Institute Working Paper 235

- "Arab Aid" from Saudi Aramco World (1979)

- Videos

- Development Cooperation Stories

- Development Cooperation Testimonials