A Modest Proposal

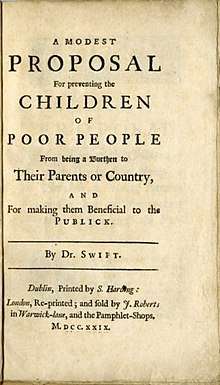

A Modest Proposal For preventing the Children of Poor People From being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and For making them Beneficial to the Publick,[1] commonly referred to as A Modest Proposal, is a Juvenalian satirical essay written and published anonymously by Jonathan Swift in 1729. The essay suggests that the impoverished Irish might ease their economic troubles by selling their children as food to rich gentlemen and ladies. This satirical hyperbole mocked heartless attitudes towards the poor, as well as British policy toward the Irish in general.

| |

| Author | Jonathan Swift |

|---|---|

| Genre | Satirical essay |

Publication date | 1729 |

In English writing, the phrase "a modest proposal" is now conventionally an allusion to this style of straight-faced satire.

Synopsis

Swift's essay is widely held to be one of the greatest examples of sustained irony in the history of the English language. Much of its shock value derives from the fact that the first portion of the essay describes the plight of starving beggars in Ireland, so that the reader is unprepared for the surprise of Swift's solution when he states: "A young healthy child well nursed, is, at a year old, a most delicious nourishing and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee, or a ragout."[1]

Swift goes to great lengths to support his argument, including a list of possible preparation styles for the children, and calculations showing the financial benefits of his suggestion. He uses methods of argument throughout his essay which lampoon the then-influential William Petty and the social engineering popular among followers of Francis Bacon. These lampoons include appealing to the authority of "a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London" and "the famous Psalmanazar, a native of the island Formosa" (who had already confessed to not being from Formosa in 1706).

In the tradition of Roman satire, Swift introduces the reforms he is actually suggesting by paralipsis:

Therefore let no man talk to me of other expedients: Of taxing our absentees at five shillings a pound: Of using neither clothes, nor household furniture, except what is of our own growth and manufacture: Of utterly rejecting the materials and instruments that promote foreign luxury: Of curing the expensiveness of pride, vanity, idleness, and gaming in our women: Of introducing a vein of parsimony, prudence and temperance: Of learning to love our country, wherein we differ even from Laplanders, and the inhabitants of Topinamboo: Of quitting our animosities and factions, nor acting any longer like the Jews, who were murdering one another at the very moment their city was taken: Of being a little cautious not to sell our country and consciences for nothing: Of teaching landlords to have at least one degree of mercy towards their tenants. Lastly, of putting a spirit of honesty, industry, and skill into our shop-keepers, who, if a resolution could now be taken to buy only our native goods, would immediately unite to cheat and exact upon us in the price, the measure, and the goodness, nor could ever yet be brought to make one fair proposal of just dealing, though often and earnestly invited to it. Therefore I repeat, let no man talk to me of these and the like expedients, 'till he hath at least some glympse of hope, that there will ever be some hearty and sincere attempt to put them into practice.

Population solutions

George Wittkowsky argued that Swift's main target in A Modest Proposal was not the conditions in Ireland, but rather the can-do spirit of the times that led people to devise a number of illogical schemes that would purportedly solve social and economic ills.[2] Swift was especially attacking projects that tried to fix population and labour issues with a simple cure-all solution.[3] A memorable example of these sorts of schemes "involved the idea of running the poor through a joint-stock company".[3] In response, Swift's Modest Proposal was "a burlesque of projects concerning the poor"[4] that were in vogue during the early 18th century.

A Modest Proposal also targets the calculating way people perceived the poor in designing their projects. The pamphlet targets reformers who "regard people as commodities".[5] In the piece, Swift adopts the "technique of a political arithmetician"[6] to show the utter ridiculousness of trying to prove any proposal with dispassionate statistics.

Critics differ about Swift's intentions in using this faux-mathematical philosophy. Edmund Wilson argues that statistically "the logic of the 'Modest proposal' can be compared with defence of crime (arrogated to Marx) in which he argues that crime takes care of the superfluous population".[6] Wittkowsky counters that Swift's satiric use of statistical analysis is an effort to enhance his satire that "springs from a spirit of bitter mockery, not from the delight in calculations for their own sake".[7]

Rhetoric

Charles K. Smith argues that Swift's rhetorical style persuades the reader to detest the speaker and pity the Irish. Swift's specific strategy is twofold, using a "trap"[8] to create sympathy for the Irish and a dislike of the narrator who, in the span of one sentence, "details vividly and with rhetorical emphasis the grinding poverty" but feels emotion solely for members of his own class.[9] Swift's use of gripping details of poverty and his narrator's cool approach towards them create "two opposing points of view" that "alienate the reader, perhaps unconsciously, from a narrator who can view with 'melancholy' detachment a subject that Swift has directed us, rhetorically, to see in a much less detached way."[9]

Swift has his proposer further degrade the Irish by using language ordinarily reserved for animals. Lewis argues that the speaker uses "the vocabulary of animal husbandry"[10] to describe the Irish. Once the children have been commodified, Swift's rhetoric can easily turn "people into animals, then meat, and from meat, logically, into tonnage worth a price per pound".[10]

Swift uses the proposer's serious tone to highlight the absurdity of his proposal. In making his argument, the speaker uses the conventional, textbook-approved order of argument from Swift's time (which was derived from the Latin rhetorician Quintilian).[11] The contrast between the "careful control against the almost inconceivable perversion of his scheme" and "the ridiculousness of the proposal" create a situation in which the reader has "to consider just what perverted values and assumptions would allow such a diligent, thoughtful, and conventional man to propose so perverse a plan".[11]

Influences

Scholars have speculated about which earlier works Swift may have had in mind when he wrote A Modest Proposal.

Tertullian's Apology

James William Johnson argues that A Modest Proposal was largely influenced and inspired by Tertullian's Apology: a satirical attack against early Roman persecution of Christianity. Johnson believes that Swift saw major similarities between the two situations.[12] Johnson notes Swift's obvious affinity for Tertullian and the bold stylistic and structural similarities between the works A Modest Proposal and Apology.[13] In structure, Johnson points out the same central theme, that of cannibalism and the eating of babies as well as the same final argument, that "human depravity is such that men will attempt to justify their own cruelty by accusing their victims of being lower than human".[12] Stylistically, Swift and Tertullian share the same command of sarcasm and language.[12] In agreement with Johnson, Donald C. Baker points out the similarity between both authors' tones and use of irony. Baker notes the uncanny way that both authors imply an ironic "justification by ownership" over the subject of sacrificing children—Tertullian while attacking pagan parents, and Swift while attacking the English mistreatment of the Irish poor.[14]

Defoe's The Generous Projector

It has also been argued that A Modest Proposal was, at least in part, a response to the 1728 essay The Generous Projector or, A Friendly Proposal to Prevent Murder and Other Enormous Abuses, By Erecting an Hospital for Foundlings and Bastard Children by Swift's rival Daniel Defoe.[15]

Mandeville's Modest Defence of Publick Stews

Bernard Mandeville's Modest Defence of Publick Stews asked to introduce public and state controlled bordellos. The 1726 paper acknowledges women's interests and – while not being a completely satirical text – has also been discussed as an inspiration for Jonathan Swift's title.[16][17] Mandeville had by 1705 already become famous for the Fable of The Bees and deliberations on private vices and public benefits.

John Locke's First Treatise of Government

John Locke commented: "Be it then as Sir Robert says, that Anciently, it was usual for Men to sell and Castrate their Children. Let it be, that they exposed them; Add to it, if you please, for this is still greater Power, that they begat them for their Tables to fat and eat them: If this proves a right to do so, we may, by the same Argument, justifie Adultery, Incest and Sodomy, for there are examples of these too, both Ancient and Modern; Sins, which I suppose, have the Principle Aggravation from this, that they cross the main intention of Nature, which willeth the increase of Mankind, and the continuation of the Species in the highest perfection, and the distinction of Families, with the Security of the Marriage Bed, as necessary thereunto". (First Treatise, sec. 59).

Economic themes

Robert Phiddian's article "Have you eaten yet? The Reader in A Modest Proposal" focuses on two aspects of A Modest Proposal: the voice of Swift and the voice of the Proposer. Phiddian stresses that a reader of the pamphlet must learn to distinguish between the satirical voice of Jonathan Swift and the apparent economic projections of the Proposer. He reminds readers that "there is a gap between the narrator's meaning and the text's, and that a moral-political argument is being carried out by means of parody".[18]

While Swift's proposal is obviously not a serious economic proposal, George Wittkowsky, author of "Swift's Modest Proposal: The Biography of an Early Georgian Pamphlet", argues that to understand the piece fully it is important to understand the economics of Swift's time. Wittowsky argues that not enough critics have taken the time to focus directly on the mercantilism and theories of labour in 18th century England. "[I]f one regards the Modest Proposal simply as a criticism of condition, about all one can say is that conditions were bad and that Swift's irony brilliantly underscored this fact".[19]

"People are the riches of a nation"

At the start of a new industrial age in the 18th century, it was believed that "people are the riches of the nation", and there was a general faith in an economy that paid its workers low wages because high wages meant workers would work less.[20] Furthermore, "in the mercantilist view no child was too young to go into industry". In those times, the "somewhat more humane attitudes of an earlier day had all but disappeared and the laborer had come to be regarded as a commodity".[18]

Louis A. Landa composed a conducive analysis when he noted that it would have been healthier for the Irish economy to more appropriately utilize their human assets by giving the people an opportunity to "become a source of wealth to the nation" or else they "must turn to begging and thievery".[21] This opportunity may have included giving the farmers more coin to work for, diversifying their professions, or even consider enslaving their people to lower coin usage and build up financial stock in Ireland. Landa wrote that, "Swift is maintaining that the maxim—people are the riches of a nation—applies to Ireland only if Ireland is permitted slavery or cannibalism"[22]

Landa presents Swift's A Modest Proposal as a critique of the popular and unjustified maxim of mercantilism in the 18th century that "people are the riches of a nation".[21] Swift presents the dire state of Ireland and shows that mere population itself, in Ireland's case, did not always mean greater wealth and economy.[22] The uncontrolled maxim fails to take into account that a person who does not produce in an economic or political way makes a country poorer, not richer.[22] Swift also recognises the implications of this fact in making mercantilist philosophy a paradox: the wealth of a country is based on the poverty of the majority of its citizens.[22] Swift however, Landa argues, is not merely criticising economic maxims but also addressing the fact that England was denying Irish citizens their natural rights and dehumanising them by viewing them as a mere commodity.[22]

The public's reaction

Swift's essay created a backlash within the community after its publication. The work was aimed at the aristocracy, and they responded in turn. Several members of society wrote to Swift regarding the work. Lord Bathurst's letter intimated that he certainly understood the message, and interpreted it as a work of comedy:

February 12, 1729–30:

"I did immediately propose it to Lady Bathurst, as your advice, particularly for her last boy, which was born the plumpest, finest thing, that could be seen; but she fell in a passion, and bid me send you word, that she would not follow your direction, but that she would breed him up to be a parson, and he should live upon the fat of the land; or a lawyer, and then, instead of being eat himself, he should devour others. You know women in passion never mind what they say; but, as she is a very reasonable woman, I have almost brought her over now to your opinion; and having convinced her, that as matters stood, we could not possibly maintain all the nine, she does begin to think it reasonable the youngest should raise fortunes for the eldest: and upon that foot a man may perform family duty with more courage and zeal; for, if he should happen to get twins, the selling of one might provide for the other. Or if, by any accident, while his wife lies in with one child, he should get a second upon the body of another woman, he might dispose of the fattest of the two, and that would help to breed up the other.

The more I think upon this scheme, the more reasonable it appears to me; and it ought by no means to be confined to Ireland; for, in all probability, we shall, in a very little time, be altogether as poor here as you are there. I believe, indeed, we shall carry it farther, and not confine our luxury only to the eating of children; for I happened to peep the other day into a large assembly [Parliament] not far from Westminster-hall, and I found them roasting a great fat fellow, [Walpole again] For my own part, I had not the least inclination to a slice of him; but, if I guessed right, four or five of the company had a devilish mind to be at him. Well, adieu, you begin now to wish I had ended, when I might have done it so conveniently".[23]

Modern usage

A Modest Proposal is included in many literature courses as an example of early modern western satire. It also serves as an introduction to the concept and use of argumentative language, lending itself to secondary and post-secondary essay courses. Outside of the realm of English studies, A Modest Proposal is included in many comparative and global literature and history courses, as well as those of numerous other disciplines in the arts, humanities, and even the social sciences.

The essay's approach has been copied many times. In his book A Modest Proposal (1984), the evangelical author Frank Schaeffer emulated Swift's work in a social conservative polemic against abortion and euthanasia, imagining a future dystopia that advocates recycling of aborted embryos, fetuses, and some disabled infants with compound intellectual, physical and physiological difficulties. (Such Baby Doe Rules cases were then a major concern of the US anti-abortion movement of the early 1980s, which viewed selective treatment of those infants as disability discrimination.) In his book A Modest Proposal for America (2013), statistician Howard Friedman opens with a satirical reflection of the extreme drive to fiscal stability by ultra-conservatives.

In the 1998 edition of The Handmaid's Tale by Margaret Atwood there is a quote from A Modest Proposal before the introduction.[24]

A Modest Video Game Proposal is the title of an open letter sent by activist/former attorney Jack Thompson on 10 October 2005. He proposed that someone should "create, manufacture, distribute, and sell a video game" that would allow players to act out a scenario in which the game character kills video game developers.[1]

Hunter S. Thompson's Fear and Loathing in America: The Brutal Odyssey of an Outlaw Journalist includes a letter in which he uses Swift's approach in connection with the Vietnam War. Thompson writes a letter to a local Aspen newspaper informing them that, on Christmas Eve, he is going to use napalm to burn a number of dogs and hopefully any humans they find. The letter protests against the burning of Vietnamese people occurring overseas.

The 2012 film Butcher Boys, written by Kim Henkel, is said to be loosely based on Jonathan Swift's A Modest Proposal. The film's opening scene takes place in a restaurant named "J. Swift's".

On November 30, 2017, Jonathan Swift's 350th birthday, The Washington Post published a column entitled 'Why Alabamians should consider eating Democrats' babies", by Alexandra Petri.[25]

In July 2019, E. Jean Carroll published a book titled What Do We Need Men For?: A Modest Proposal, discussing problematic behaviour of male humans.[26][27]

On October 3, 2019, a satirist spoke up at an event for Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, claiming that a solution to the climate crisis was "we need to eat the babies".[28] The individual also wore a T-shirt saying "Save The Planet, Eat The Children". This stunt was understood by many[29] as a modern application of A Modest Proposal.

Notes

- A Modest Proposal, by Dr. Jonathan Swift. Project Gutenberg. 27 July 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- Wittkowsky, Swift’s Modest Proposal, p. 76

- Wittkowsky, Swift’s Modest Proposal, p. 85

- Wittkowsky, Swift's Modest Proposal, p. 88

- Wittkowsky, Swift's Modest Proposal, p. 101

- Wittkowsky, Swift's Modest Proposal, p. 95

- Wittkowsky, Swift's Modest Proposal, p. 98

- Smith, Toward a Participatory Rhetoric, p. 135

- Smith, Toward a Participatory Rhetoric, p. 136

- Smith, Toward a Participatory Rhetoric, p. 138

- Smith, Toward a Participatory Rhetoric, p. 139

- Johnson, Tertullian and A Modest Proposal, p. 563

- Johnson, Tertullian and A Modest Proposal, p. 562

- Baker, Tertullian and Swift's A Modest Proposal, p. 219

- Waters, Juliet (19 February 2009). "A modest but failed proposal". Montreal Mirror. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- Eine Streitschrift…, Essay von Ursula Pia Jauch. Carl Hanser Verlag, München 2001.

- Primer, I. (15 March 2006). Bernard Mandeville's "A Modest Defence of Publick Stews": Prostitution and Its Discontents in Early Georgian England. Springer. ISBN 9781403984609.

- Phiddian, Have You Eaten Yet?, p. 6

- Phiddian, Have You Eaten Yet?, p. 3

- Phiddian, Have You Eaten Yet?, p. 4

- Landa, A Modest Proposal and Populousness, p. 161

- Landa, A Modest Proposal and Populousness, p. 165

- Swift, Jonathan; Scott, Sir Walter (1814). The Works of Jonathan Swift: Containing Additional Letters, Tracts, and Poems Not Hitherto Published; with Notes and a Life of the Author. A. Constable.

- "The Handmaid's Tale". www.goodreads.com.

- Petri, Alexandra (30 November 2017). "Why Alabamians should consider eating Democrats' babies". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- Carroll, E. Jean (21 June 2019). "Donald Trump Assaulted Me, But He's Not Alone on My List of Hideous Men". The Cut. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- "What Do We Need Men For?: A Modest Proposal | IndieBound.org". www.indiebound.org. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

- ‘We Need to Eat the Babies!’ Climate Activist Confronts AOC at New York Town Hall, retrieved 4 October 2019

- EDT, Marika Malaea On 10/4/19 at 12:24 AM (4 October 2019). "'Eat the babies!': Twitter reacts to a surprise ending to the Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez town hall meeting". Newsweek. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

References

- Baker, Donald C (1957), "Tertullian and Swift's A Modest Proposal", The Classical Journal, 52: 219–220

- Johnson, James William (1958), "Tertullian and A Modest Proposal", Modern Language Notes, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 73 (8): 561–563, doi:10.2307/3043246, JSTOR 3043246 (subscription needed)

- Landa, Louis A (1942), "A Modest Proposal and Populousness", Modern Philology, 40 (2): 161–170, doi:10.1086/388567

- Phiddian, Robert (1996), "Have You Eaten Yet? The Reader in A Modest Proposal", SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900, Rice University, 36 (3): 603–621, doi:10.2307/450801, hdl:2328/746, JSTOR 450801

- Smith, Charles Kay (1968), "Toward a Participatory Rhetoric: Teaching Swift's Modest Proposal", College English, National Council of Teachers of English, 30 (2): 135–149, doi:10.2307/374449, JSTOR 374449

- Wittkowsky, George (1943), "Swift's Modest Proposal: The Biography of an Early Georgian Pamphlet", Journal of the History of Ideas, University of Pennsylvania Press, 4 (1): 75–104, doi:10.2307/2707237, JSTOR 2707237

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- A Modest Proposal (CELT)

- A Modest Proposal (Gutenberg)

- A Modest Proposal – Annotated text aligned to Common Core Standards

- A Modest Proposal BBC Radio 4 In Our Time with Melvyn Bragg

- 'A modest proposal For preventing the children of poor people From being a Burthen to their Parents or the Country, And for making them Beneficial to the publick. The Third Edition, Dublin, Printed: And Reprinted at London, for Weaver Bickerton, in Devereux-Court near the Middle-Temple, 1730.

- ' Proposal to eat the children' a short movie based upon Swift's novel.