George Ritzer

George Ritzer (born October 14, 1940) is an American sociologist, professor, and author who studies globalization, metatheory, patterns of consumption, and modern and postmodern social theory. His most notable contribution to date is his concept of McDonaldization, which draws upon Max Weber's idea of rationalization through the lens of the fast food industry. In addition to creating his own theories, Ritzer has also written many general sociology books, including Introduction to Sociology (2012) as well as Essentials to Sociology (2014), and modern and postmodern social theory textbooks. He coined the term “McDonaldization”.[2] Currently, Ritzer is a Distinguished Professor at the University of Maryland, College Park.

George Ritzer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | October 14, 1940 New York City, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater |

|

Main interests | |

Notable ideas |

|

Biography

Early life

Ritzer was born in 1940 to a Jewish family in upper Manhattan, New York City. His father and mother were employed as a taxi cab driver and secretary, respectively, in order to support him and his younger brother. Ritzer later described his upbringing as "upper lower class".[3] When his father contracted a strange illness, speculated to be from his job as a taxi driver, Ritzer's mother had to break open the family's piggy bank, where they stored half dollars, in order to provide for the family.[3] Despite dealing with some tough economic times, he never felt deprived relative to others while growing up in a "working-class, multi-ethnic neighborhood".[3]

Education and early employment

Ritzer graduated from the Bronx High School of Science in 1958,[4] stating to have "encountered the brightest people I have ever met in my life".[3] While at Bronx High School of Science, Ritzer received a New York State Regents Scholarship which would follow him to whichever college he chose to attend.[3]

Ritzer began his higher education at City College of New York, a free college at the time. His scholarship in addition to the free college tuition proved to be a benefit to the economic positioning of the Ritzer family.[3] While at CCNY, Ritzer initially planned to focus on business, but he later changed his major to accounting.

After graduating from CCNY in 1962,[4] Ritzer decided that he was interested in pursuing business again. He was accepted into the M.B.A. program at the University of Michigan Ann Arbor, where he received a partial scholarship. While at Michigan, his official academic interest was human relations; however, he had many other intellectual hobbies, such as reading Russian novels. Ritzer reported that at Michigan, as he was able to grow and improve as a student. However, during his time at Michigan, he remembers being heavily involved in global events occurring at the time. He reports memories of going to the Michigan Union to watch the happenings of the Cuban Missile Crisis.[3]

After graduating from The University of Michigan in 1964,[4] Ritzer began working in personnel management for the Ford Motor Company; however, this proved to be a negative experience for him. His managers mistakenly hired three people, more than was necessary, for the one job, leaving him idle and unoccupied. As he once said: "[i]f we had two hours of work a day, it was a lot."[3] Nevertheless, he was always expected to appear busy. He would constantly wander around the factory for hours observing people working, causing many of the workers and foremen to become hostile towards him. Moreover, Ritzer also found problems within the management structure at Ford. Most of the younger people with advanced degrees defied their less educated authorities. Ritzer said, "I'd like to see a society in which people are free to be creative, rather than having their creativity constrained or eliminated." [5] Furthermore, he found himself constrained and unable to do anything creative while working at Ford, encouraging him to apply to Ph.D. programs.[3]

Ritzer enrolled in Cornell University's School of Labor and Industrial Relations Ph.D. program in Organizational Behavior in 1965.[3] There, his adviser Harrison Trice suggested that he minor in sociology. After a conversation with the head of the department, Gordon Streib, Ritzer realized that he knew nothing about sociology and was then urged to read "Broom and Selznick’s Introduction to Sociology" and found himself enthralled with the subject matter.[3] He continued to succeed in sociology courses at the graduate level. As a testament to his interest and dedication to the subject, he received an A+ on a 102-page paper he wrote for a course on American society. His professor stated that the paper was "too long not to be good".[3] This experience as well as out-reading the other sociology students in a small seminar with Margaret Cussler allowed Ritzer to become more confident as a sociology student due to his ability to outwork the competition. He attributed his talent of being able to compete with well-read and experienced sociology students to his work ethic.[3]

Academic career

After graduating from Cornell in 1968, Ritzer received various academic appointments at universities around the United States and the world:[6]

- 1968-1970: Assistant Professor, Tulane University

- 1970-1974: Associate Professor, University of Kansas

- 1974-2001: Professor, University of Maryland

- 1984: Visiting Exchange Professor, University of Surrey, England.

- 1988: Visiting Professor, Shanghai University, China; Peking University, Beijing, China

- 1990: Visiting Exchange Professor, University of Surrey, England

- 1996: Visiting Professor, University of Tampere, Finland

- 2001: Visiting Professor, University of Bremen, Germany

- 2001–present: Distinguished University Professor, University of Maryland, College Park

- 2002, 2004-2008: Visiting Professor, Associazione per l’Istituzione della Libera Università Nuorese, Sardinia, Italy

- 2012: Visiting Professor, University of Salzburg, Austria

- 2013: Visiting Scholar, Center for Advanced Study, University of Munich, Germany

Main ideas

Although known as a sociologist, Ritzer never earned a degree in sociology; he was trained in psychology and business. As Ritzer said in a later interview, "I basically trained myself as a social theorist, and so I had to learn it all as I went." Despite this challenge, Ritzer found that not being trained in social theory was actually advantageous for him, simply because his reasoning was not limited to a particular theoretical perspective.[3] Listed are his biggest accomplishments in social theory:

McDonaldization

George Ritzer wrote The McDonaldization of Society.[7]

Ritzer's idea of McDonaldization is an extension of Max Weber's (1864–1920) classical theory of the rationalization of modern society and culture. Weber famously used the terminology "iron cage" to describe the stultifying, Kafkaesque effects of bureaucratized life,[8] and Ritzer applied this idea to an influential social system in the twenty-first century: McDonald's. Ritzer argues that McDonald's restaurants have become the better example of current forms of instrumental rationality and its ultimately irrational and harmful consequences on people[9] Ritzer shared similar views as Max Weber about the topic of rationalization. While Weber claims that “the most sublime values have retreated from public life”, Ritzer claims that even our food is subject to rationalization, whether it is “the McDonaldized experience or the steak dinner that is subjected to the fact that it contains 2,000 calories and 100 grams of fat."[10]”Ritzer identifies four rationalizing dimensions of McDonald's that contribute to the process of McDonaldization, claiming that McDonald's aims to increase:

- Efficiency: McDonald's delivers products quickly and easily without inputting an excessive amount of money. The "McDonald's model" and therefore the McDonald's operations follow a predesigned process that leads to a specified end, using productive means.[11] The efficiency of the McDonald's model has infiltrated other modern day services such as completing tax forms online, easy weight loss programs, The Walt Disney Company FASTPASSes, and online dating services, eHarmony and match.com.[11][12]

- Calculability: America has grown to connect the quantity of a product with the quality of a product and that "bigger is better".[11] The "McDonald's model" is influential in this conception due to providing a lot of food for not that much money. While the end products feed into the connection between the quantity and quality of the product, so does the McDonald's production process. Throughout the food production, everything is standardized and highly calculated: the size of the beef patty, the amount of french fries per order, and the time spent in a franchise. The high calculability of the McDonald's franchise also extends over into academics. It is thought that the academic experience, in high school and higher education, can be quantified into one number, the GPA. Also, calculability leads to the idea that the longer the resume or list of degrees, the better the candidate, during an application process. In addition to academics being affected by the McDonaldization in society, sports, specifically basketball have also been affected. It used to be that basketball was a more laid-back, slow-paced sort of game, yet through the creation of fast-food and McDonald's, a shot clock was added to increase not only the speed of the game, but also the number of points scored.[11]

- Predictability: Related to calculability, customers know what to expect from a given producer of goods or services. For example, customers know that every Big Mac from McDonald's is going to be the same as the next one; there is an understood predictability to the menu as well as the overall experience. In order to maintain the predictability for each franchise, there has to be "discipline, order, systematization, formalization, routine, consistency, and a methodical operation".[11] The predictability of the McDonald's franchise also appears through the golden arches in front of every franchise as well as the scripts that the employees use on the customers. The Walt Disney Company also has regulations in place, like dress code for men and women, in order to add to the predictability of each amusement park or Disney operation. Predictability has also extended into movie sequels and TV shows. With each movie sequel, like Spy Kids 4, or TV show, Law & Order and its spinoffs, the plot is predictable and usually follow a preconceived model.[11]

- Control: McDonald's restaurants pioneered the idea of highly specialized tasks for all employees to ensure that all human workers are operating at exactly the same level. This is a way to keep a complicated system running smoothly; rules and regulations that make efficiency, calculability, and predictability possible.[12] Oftentimes, the use of non-human technology, such as computers, is used. The McDonald's food is already "pre-prepared", the potatoes are already cut and processed, just needing to be fried and heated, and the food preparation process is monitored and tracked. The computers tell the managers how many hamburgers are needed at the lunchtime rush and other peak times and the size and shape of the pickles as well as how many go on a hamburger is managed and control.[11] The control aspect of McDonaldization has extended to other businesses, Sylvan Learning and phone operating systems, and even birth and death. Every step of the learning process at Sylvan, the U-shaped tables and instruction manuals, is controlled as well as each step of the birthing process, in modern-day hospitals, and the process of dying.[11]

McDonaldization is profitable, desirable, and at the cutting edge of technological advances. Many "McDonald's" aspects of society are beneficial to the advancement and enhancement of human life. Some claim that rationalization leads to "more egalitarian" societies. For example, supermarkets and large grocery stores offer variety and availability unlike smaller farmer's markets from generations past. The McDonaldization of society also allows operations to be more productive, improve the quality of some products, and produce services and products at lower cost.[11] The Internet has provided countless new services to people that were previously impossible, such as checking bank statements without having to go to a bank or being able to purchase things online without leaving the house.[13] These things are all positive effects of the rationalization and McDonaldization of society.

However, McDonaldization also alienates people and creates a disenchantment of the world. The increased standardization of society dehumanizes people and institutions. The "assembly line" feel of fast-food restaurants is transcending many other facets of life and removing humanity from previously human experiences.[14][15] Through implementing machines and computers in society, humans can start to "behave like machines" and therefore "become replaced by machines".[11]

Consumption

An early admirer of Jean Baudrillard’s Consumer Society (1970),[16] Ritzer is a leading proponent of the study of consumption. In addition to The McDonaldization of Society, the most important sources for Ritzer’s sociology of consumption are his edited Explorations in the Sociology of Consumption: Fast Food Restaurants, Credit Cards and Casinos (2001), Enchanting a Disenchanted World: Revolutionizing the Means of Consumption (2nd edition 2005, 3rd edition 2009), and Expressing America: A Critique of the Global Credit-Card Society (1995). Ritzer is also a founding editor, with Don Slater, of Sage's Journal of Consumer Culture.[6]

Prosumption

First coined by Alvin Toffler in 1980, the term prosumption is used by Ritzer and Jurgenson,[17] to break down the false dichotomy between production and consumption and describe the dual identity of economic activities. Ritzer argues that prosumption is the primordial form of economic activities, and the current ideal separation between production and consumption is aberrant and distorted due to the effect of both Industrial Revolution and post-WWII American consumption boom. It has only recently become popularly acknowledged that the existence of prosumption as activities on the internet and Web 2.0 resemble prosumption much more so than production or consumption individually. Various online activities require the input of consumers such as Wikipedia entries, Facebook profiles, Twitter, Blog, Myspace, Amazon preferences, eBay auctions, Second Life, etc. Ritzer argues that we should view all economic activities on a continuum of prosumption with prosumption as production (p-a-p) and prosumption as consumption (p-a-c) on each pole.

Something vs. nothing

According to Ritzer, "Something" is a locally conceived and controlled social form that is comparatively rich in distinctive substantive content. It also describes things as being fairly unusual. "Nothing" is "a social form that is generally centrally conceived, controlled and comparatively devoid of distinctive substantive content" [18] "Nothing" usually aims at the standardized and homogenous, while "something" refers to things that are personal or have local flavor. Examples of "nothing" are McDonald's, Wal-Mart, Starbucks, credit cards, and the Internet. Examples of "something" are local sandwich shops, local hardware stores, family arts and crafts places, or a local breakfast cafe.[19] Ritzer believes that things that embody the "nothing" component of this dichotomy are taking over and pushing "something" out of society. He explains the advantages and disadvantages of both "something" and "nothing" in The McDonaldization of Society.[15]

Globalization

In Ritzer's research, globalization refers to the rapidly increasing worldwide integration and interdependence of societies and cultures.[20] This book presents a sophisticated argument about the nature of globalization in terms of the consumption of goods and services. He defines it as involving a worldwide diffusion of practices, relations, and forms of social organization and the growth of global consciousness.[21] The concept of "something" vs. "nothing" plays a large part in understanding Ritzer's Globalization. Society is becoming bombarded with "nothing" and Ritzer seems to believe that the globalization of "nothing" is almost unstoppable [22] Ritzer's aforementioned The Globalization of Nothing (2004/2007) stakes out a provocative perspective in the ongoing and voluminous globalization discourse. For Ritzer, globalization typically leads to consumption of vast quantities of serial social forms that have been centrally conceived and controlled – one McDonald's hamburger, i.e., one instance of nothing again and again- dominates social life (Ritzer, George. 2004. The Globalization of Nothing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press). To better understand globalization, it can be broken down into a few characteristics:

- The beginning of global communication through different media like television and the Internet

- The formation of a "global consciousness"[14]

In addition to The Globalization of Nothing, Ritzer has edited The Blackwell Companion to Globalization (2007), written Globalization: A Basic Text (2009), and edited an Encyclopedia of Globalization (forthcoming). Insight into Ritzer's distinctive approach to globalization is available via a special review symposium in the Sage journal Thesis Eleven (Number 76, February 2004).[23]

Grobalization

In his book The Globalization of Nothing (2004), Ritzer quotes that globalization consists of glocalization and grobalization.[24] Grobalization, a term coined by Ritzer himself, refers to "imperialistic ambitions of nations, corporations, organizations, and the like and their desire, indeed need, to impose themselves on various geographic areas".[25] As opposite to glocalization, grobalization aims to "overwhelm local".[24] Its ultimate goal is to see profit grow through unilateral homogenization, thus earning its name grobalization. Capitalism, Americanization, and McDonaldization are all parts of grobalization.[25]

Grobalization involves three motor forces: capitalism, McDonaldization, and Americanization. Grobalization creates a world where:

- Things are more homogenous and ubiquitous.

- Larger forces overwhelm the power of people to adapt and innovate in ways that preserve their autonomy.

- Social processes are coercive, determining the nature of local communities, which have little room to maneuver.

- Consumer goods and the media are key forces that largely dictate the nature of the self and the groups a person joins.[26]

Ritzer provides American textbook as an example of grobalization. In his book, The Globalization of Nothing, he quotes that textbooks are "oriented to rationalizing, McDonaldizing, the communication of information."[27] Students, rather than evaluating the competing ideas, instead absorb the information given to them. Yet, these textbooks are surprisingly sold out worldwide, only to be slightly revised to reflect local standards.[27]

Glocalization

Glocalization is a combination of the words "globalization" and "localization" used to describe a product or service that is developed and distributed globally, but is also fashioned to accommodate the user or consumer in a local market, causing the products, or results of glocalization, to vary depending on different locations. The local individuals are able to manipulate their own situation in the world and become creative agents in what products and services are represented in their local environment within the glocalized world.[28] Ritzer further explains Glocalization as a relatively benign process that is closest to the "something" end of things. It creates variety and heterogeneity within society.[29]

Metatheory

Metatheory can be defined as the attainment of a deeper understanding of theory, the creation of new theory, and the creation of an overarching theoretical perspective. There are three types of metatheorizing: Mu, Mp, and Mo. Through the application of the three subsets of metatheory, Ritzer argues that the field of sociology can create a stronger foundation, experience "rapid and dramatic growth", and generally increase not only the knowledge of metatheory but social theory in general.[30]

The first category of metatheory (Mu), aims at being a means of attaining a deeper understanding of theory. Within the greater category of Mu, Ritzer establishes four other subsets: internal-intellectual, internal-social, external-intellectual, and external-social. The internal-intellectual sector of Mu identifies the "schools of thought" and the structure of current sociologists and social theories. The internal-social subtype identifies connections between sociologists and connections between sociologists and society. The last two subsets of Mu are looking more at the macrolevel of sociology than the other two subsets. The third subtype of Mu is the external-intellectual view of sociology; it looks at different studies and their concepts, tools, and ideas in order to apply these aspects to sociology. The fourth, and final, subset is external-social where the impact of social theory in a larger societal setting is studied.[30]

The second (Mp), aims at being a prelude to theory development. New social theory is created due to the complex study and interpretation of other sociologists. For example, Karl Marx's theories are based on Hegel's theories. The theories of the American sociologist, Talcott Parsons, are based on the theories of Émile Durkheim, Max Weber, Vilfredo Pareto, and Thomas Humphrey Marshall.[30]

The last (Mo), aims at being a source of perspectives that overarch sociological theory.[30] Influenced by Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), Ritzer has long advocated the view that social theory is improved by systematic, comparative and reflexive attention to implicit conceptual structures and oft-hidden assumptions.[31]

Key works include Sociology: A Multiple Paradigm Science (1975), Toward an Integrated Sociological Paradigm (1981), Metatheorizing in Sociology (1991), and Explorations in Social Theory: From Metatheorizing to Rationalization (2001). See also Ritzer’s edited Metatheorizing (1992).

Modern and postmodern social theory

Ritzer is known to generations of students as the author of numerous comprehensive introductions and compendia in social theory. Postmodern society is a consumer society that invents new means of consumption, such as credit cards, shopping malls, and shopping networks. Today, "Capitalism needs us to keep on spending at ever-increasing levels to be and remain capitalism." [32] As with several of Ritzer's other principal works, many are translated into languages as diverse as Chinese, Russian, Persian, Hebrew and Portuguese.[6] Key volumes in this genre include The Sociological Theory (7th edition 2008), Classical Sociological Theory (5th edition 2008), and Modern Sociological Theory (7th edition 2008), Encyclopedia of Social Theory (2 vols. 2005), and Postmodern Social Theory (1997). For convenient access to many of Ritzer's substantive contributions to modern and postmodern social theorizing, see Explorations in Social Theory: From Metatheorizing to Rationalization (2001) as well as more recent work often co-authored with his many students, such as (with J. Michael Ryan) "Postmodern Social Theory and Sociology: On Symbolic Exchange with a ‘Dead’ Theory," in Reconstructing Postmodernism: Critical Debates (2007).

Works

George Ritzer has published many monographs and textbooks. He has edited three encyclopedias, including the Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. He has written approximately one hundred scholarly articles in respected journals.[6]

Sociology: A Multiple Paradigm Science (1975, 1980)

Based on his original article appearing in the American Sociologist,[33] this book provides a foundation for Ritzer's other works on metatheory. The piece applies Thomas Kuhn's idea of scientific paradigms to sociology and demonstrating that sociology is a science consisting of multiple paradigms. Ritzer also discusses what implications this has for the field of sociology.[31]

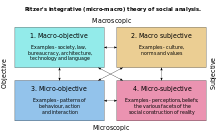

Toward an Integrated Sociological Paradigm (1981)

In this book, Ritzer contends that sociology needs an integrated paradigm in order to add to the extant paradigms noted in Sociology: A Multiple Paradigm Science. Ritzer proposes an integrated paradigm dealing with the interrelationships between the many levels of social reality.[34]

The McDonaldization of Society (1993)

In this provocative book, George Ritzer explores how Weber's classic thoughts on rationalization take on new vitality and meaning when applied to the process of McDonaldization. He describes this as the process by which the principles of the fast food restaurants are coming to dominate more and more sectors of society in the United States as well as the rest of the world. George Ritzer is most well known for The McDonaldization of Society, which has five different editions and has sold over 175,000 copies as of 2007.[2]

Ritzer shows how Weber's central characteristics of rationalized systems - efficiency, predictability, calculability, substitution of non-human for human technology and control over uncertainty - have found widespread expression in a broad range of organized human activity, including travel, consumer products and services, education, leisure, politics and religion as well as in the fast food industry.[35]

The Blackwell Companion to Major Contemporary Social Theorists (2003)

Guide to thirteen leading social theorists: Robert K. Merton, Erving Goffman, Richard M. Emerson, James Coleman, Harold Garfinkel, Daniel Bell, Norbert Elias, Michel Foucault, Jürgen Habermas, Anthony Giddens, Pierre Bourdieu, Jean Baudrillard, Judith Butler.[36] During the Introduction of this book, Ritzer writes, “Although any list of theorists covered in a collection such as this one can be read as an official cannon, this book is intended to be used as ‘cannon fodder’ in an open, contestable process of theory construction and reconstruction."[36]

The McDonaldization of Society: 20th Anniversary Edition (2012)

Ritzer's McDonaldization of Society, now celebrating its 20th anniversary, continues to stand as one of the pillars of modern-day sociological thought. By linking theory to 21st-century culture, this book resonates with audiences in a way that few other books do, opening their eyes to many current issues, especially in consumption and globalization. As in previous editions, the book has been updated and it offers new discussions of, among others, In-N-Out Burger and Pret a Manger as possible antitheses of McDonaldization. The biggest change, however, is that the book has been streamlined to offer an even clearer articulation of the McDonaldization thesis. The final chapter also looks at "The DeMcDonaldization of Society", and concludes that while it is occurring on the surface, McDonaldization is alive and well.[37]

The Globalization of Nothing, Second Edition (2007)

The Globalization of Nothing, Second Edition emphasizes the processes of globalization and how they relate to McDonaldization. As before, this book is structured around four sets of concepts addressing the issues of: "places/non-places," "things/non-things," "people/non-people," and "services/non-services." By drawing upon salient examples from everyday life, Ritzer invites the reader to examine the nuances of these concepts in conjunction with the paradoxes within the process of the globalization of nothing. Critical questions are raised throughout, and the reader is compelled not only to seek answers to these questions, but also to critically evaluate the questions as well as their answers. The current edition features a greater emphasis on the main topic of globalization: a new first chapter offers an introductory overview of globalization and globalization theory, outlining the unique ways in which these topics are addressed throughout the text. It also delves into two subprocesses of globalization — "glocalization" and "grobalization."[28]

Enchanting a Disenchanted World, Third Edition (2009)

Enchanting a Disenchanted World, Third Edition examines Disney, malls, cruise lines, Las Vegas, the World Wide Web, McDonald's, Planet Hollywood, credit cards, and all the other ways we now consume. The current edition was updated to reflect the recent economic recession and the impact of the internet. Ritzer continues to explore this book's central thesis: that our society has undergone fundamental change because of the way and the level at which we consume. The third edition demonstrates how we have created new "cathedrals" of consumption (places that enchant us so as to entice us to stay longer and consume more) while continuing to take capitalism to a new level. These places of consumption, whether in our homes, the mall, or cyberspace, are in a constant state of "enchanting the disenchanted," luring us through new spectacles because their rational qualities are both necessary and deadening at the same time. The book also includes a wide range of theoretical perspectives — Marxian, Weberian, critical theory, postmodern theory — as well as a number of concepts such as hyperconsumption, implosion, simulation, and time and space to show the audience how sociological theory can be applied to everyday phenomena.[38]

Sociological Theory, Ninth Edition (2013)

George Ritzer and Jeffery Stepnisky are co-authors this book. The book is split into four parts. Part One goes into specific details about the early years of sociological theory, focusing on Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim, Max Weber, and Georg Simmel. Part Two shifts into modern sociological theories, such as Structural Functionalism, Systems Theory, Conflict Theory, varieties of Neo-Marxism Theory, Symbolic Interactionism, Ethnomethodology, Exchange, Network, and Rational Choice Theories, Contemporary Feminist Theory. Part Three covers Integrative Sociological Theory, specifically Micro-Macro and Agency-Structure Integration Part Four is focuses on contemporary Theories of Modernity, Globalization Theory, Structuralism, Poststructuralism, and Postmodern Social Theory, and Social Theory in the Twenty-First Century[39]

Leadership roles

George Ritzer has held notable positions of leadership, including [6]

- 2009-2010 – First Chair of the ASA Section-in-Formation on Global and Transnational Sociology

- 2000 - American Sociological Association Distinguished Scholarly Publication

Award Committee

- 1989–1990 Chair of Section on Theoretical Sociology, ASA

Present Positions: Editor, Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology; Editor, Journal of Consumer Culture; Associate Editor, Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change ● Editorial Board, Sociology Analysis; Consulting Editor: St. Martin Press/Worth, Series on Contemporary Social Issues; Sage of England, Series on Cultural Icons; McGraw-Hill.[1]

Personal life

Ritzer and his wife, Sue (married 1963), have two children and five grandchildren. Despite being a workaholic, he has always made time for his family. Ritzer also loves to travel, oftentimes using the work trips as a time for a mini vacation with his wife.[40]

Bibliography

- Toward an Integrated Sociological Paradigm (1981)

- Metatheorizing in Sociology (1991)

- Metatheorizing (1992)

- Expressing America: A Critique of the Global Credit Card Society (1995)

- Explorations in Social Theory: From Metatheorizing to Rationalization (2001)

- Encyclopedia of Sociology (2007)

- The Blackwell Companion to Globalization (2007)

- Globalization: A Basic Text (2009)

- Encyclopedia of Globalization (2012)

See also

References

- Ritzer, George. "Ailun". Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Rojek, Chris (23 January 2007). "George Ritzer and the Crisis of the Public Intellectual". Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies. 29: 3–21. doi:10.1080/10714410600552241.

- Dandaneau, Steve P.; Dodsworth, Robin M. (2006), "Being (George Ritzer) and Nothingness: An Interview", The American Sociologist, 37 (4): 84–96, doi:10.1007/BF02915070

- Ritzer, George (2012-05-02). "Vitae". georgeritzer.com. Word Press. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Ritzer, George. "George Ritzer".

- Ritzer, George (2008), Vita: George Ritzer (PDF), retrieved 2009-10-07

- Rojek, Chris (23 January 2007). "George Ritzer and the Crisis of the Public Intellectual". Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies. 29 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1080/10714410600552241. ISSN 1071-4413.

- Farganis, James (2010). Readings in Social Theory, 6th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0078111556.

- Ritzer, G. The McDonaldization of Society. SAGE Publications, Inc. Thousand Oaks, 1996

- Allan, Kenneth (2010). Explorations in Classical Sociological Theory: Seeing the Social World. Pine Forge Press.

- Ritzer, George (2013). The McDonaldization of Society: 20th Anniversary Edition. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. ISBN 9781452226699.

- Massey, Garth (2012). Readings For Sociology, 7th Edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 453–455. ISBN 9780393927009.

- Massey, Garth (2012). Readings For Sociology, 7th Edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 457. ISBN 9780393927009.

- Mann, Douglas (2007). Understanding society : a survey of modern social theory. Toronto: Oxford University Press. pp. 381–384. ISBN 9780195421842.

- Massey, Garth (2012). Readings For Sociology, 7th Edition. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 456. ISBN 9780393927009.

- Dandaneau, Steve P.; Dodsworth, Robin M. (2006), A Consuming Passion: An Interview with George Ritzer (PDF), retrieved 2009-06-28

- Ritzer, George; Jurgenson, Nathan (2010), "Production, Consumption, Prosumption : The nature of capitalism in the age of the digital 'prosumer'", Journal of Consumer Culture, 10: 13–36, doi:10.1177/1469540509354673

- Mann, Douglas (2007). Understanding society : a survey of modern social theory. Toronto: Oxford University Press. pp. 396–397. ISBN 9780195421842.

- Mann, Douglas (2007). Understanding society : a survey of modern social theory. Toronto: Oxford University Press. p. 398. ISBN 9780195421842.

- Ritzer, G. The Globalization of Nothing, Pine Forge Press, Thousand Oaks, 2004,

- Mann, Douglas (2007). Understanding society : a survey of modern social theory. Toronto: Oxford University Press. p. 396. ISBN 9780195421842.

- Mann, Douglas (2007). Understanding society : a survey of modern social theory. Toronto: Oxford University Press. p. 402. ISBN 9780195421842.

- Glocalization. Investopedia.

- Ritzer, George (2004). The Globalization of Nothing. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press. Xiii

- Ritzer, George (2004). The Globalization of Nothing. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press. p.73

- Mann, Douglas (2007). Understanding society : a survey of modern social theory. Toronto: Oxford University Press. p. 400. ISBN 9780195421842.

- Ritzer, George (2004). The Globalization of Nothing. Thousand Oaks: Pine Forge Press. p.175

- Ritzer, G. The Globalization of Nothing Archived 2014-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, 2nd Edition. SAGE Publications, Inc. Thousand Oaks, 2007.

- Mann, Douglas (2007). Understanding society : a survey of modern social theory. Toronto: Oxford University Press. p. 399. ISBN 9780195421842.

- Ritzer, George (1990). "Metatheorizing in Sociology". Sociological Forum. 5 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1007/BF01115134. JSTOR 684578.

- Ritzer, G. Sociology: A Multiple Paradigm Science. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 1974,

- Ritzer, George. "The New Means of Consumption: A Postmodern Analysis" (PDF). Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- The American Sociologist, Vol. 10, No. 3, August 1975 (pp. 156–167)

- Ritzer, G. Toward an Integrated Sociological Paradigm. Allyn and Bacon, Boston, 1981,

- Ritzer, G. The McDonaldization of Society. SAGE Publications, Inc. Thousand Oaks. 1993.

- Ritzer, George (2003). The Blackwell Companion to Major Classical Theorists. John Wiley and Sons.

- Ritzer, G. The McDonaldization of Society Archived 2014-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, 7th Edition. SAGE Publications, Inc. Thousand Oaks, 2012.

- Ritzer, G. Enchanting a Disenchanted World Archived 2014-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, Third Edition. SAGE Publications, Inc. 2009.

- Ritzer, George; Stepnisky, Stephen. Sociological Theory (Ninth ed.). McGraw Hill.

- Pratt, Beverly (2010-05-21). "Faculty Spotlight: George Ritzer". IMAGINE: newsblog. Department of Sociology, University of Maryland, College Park. Retrieved 20 October 2014.