Proto-globalization

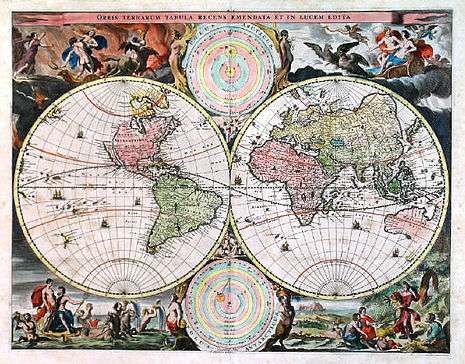

Proto-globalization or early modern globalization is a period of the history of globalization roughly spanning the years between 1600 and 1800, following the period of archaic globalization. First introduced by historians A. G. Hopkins and Christopher Bayly, the term describes the phase of increasing trade links and cultural exchange that characterized the period immediately preceding the advent of so-called "modern globalization" in the 19th century.[1]

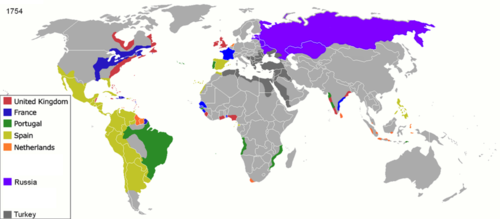

Proto-globalization distinguished itself from modern globalization on the basis of expansionism, the method of managing global trade, and the level of information exchange. The period of proto-globalization is marked by such trade arrangements as the East India Company, the shift of hegemony to Western Europe, the rise of larger-scale conflicts between powerful nations such as the Thirty Years' War, and a rise of new commodities—most particularly slave trade. The Triangular Trade made it possible for Europe to take advantage of resources within the western hemisphere. The transfer of plant and animal crops and epidemic diseases associated with Alfred Crosby's concept of The Columbian Exchange also played a central role in this process. Proto-globalization trade and communications involved a vast group including European, Muslim, Indian, Southeast Asian and Chinese merchants, particularly in the Indian Ocean region.

The transition from proto-globalization to modern globalization was marked with a more complex global network based on both capitalistic and technological exchange; however, it led to a significant collapse in cultural exchange.

Description

Although the 17th and 18th centuries saw a rise in Western Imperialism in the world system, the period of Proto-globalization involved increased interaction between Western Europe and the systems that had formed between nations in East Asia and the Middle East.[1] Proto-globalization was a period of reconciling the governments and traditional systems of individual nations, world regions, and religions with the "new world order" of global trade, imperialism and political alliances, what historian A.G. Hopkins called "the product of the contemporary world and the product of distant past."[1]

According to Hopkins, "globalization remains an incomplete process: it promotes fragmentation as well as uniformity; it may recede as well as advance; its geographical scope may exhibit a strong regional bias; its future direction and speed cannot be predicted with confidence—and certainly not by presuming that it has an 'inner logic' of its own.[1] Before proto-globalization, globalizing networks were the product of "great kings and warriors searching for wealth and honor in fabulous lands, by religious wanderers,...and by merchant princes".[2] Proto-globalization held on to and matured many aspects of archaic globalization such as the importance of cities, migrants, and specialization of labor.[3]

Proto-globalization was also marked by two main political and economic developments: "the reconfiguration of the state systems, and the growth of finance, services, and pre-industrial manufacturing".[4] A number of states at the time began to "strengthen their connections between territory, taxation, and sovereignty" despite their continuing monopoly of loyalties from their citizens.[4] The process of globalization during this time was heavily focused on material world and the labor needed for its production.[5] The proto-globalization period was a time of "improved efficiency in the transactions sector" with the generation of goods such as sugar, tobacco, tea, coffee, and opium unlike anything the archaic globalization possessed.[5] The improvement of economic management also spread to the expansion of transportation which created a complex set of connection between the West and East.[5] The expansion of trade routes led to the "green revolution" based on the plantation system and slave exportation from Africa.[5]

Precursors

During the pre-modern era early forms of globalization were already beginning to affect a world system, marking a period that historian A. G. Hopkins has called archaic globalization.[1] The world system leading up to proto-globalization was one that hinged on one or more hegemonic powers assimilating neighboring cultures into their political system, waging war on other nations, and dominating world trade.[6]

A major hegemony in archaic globalization was the Roman Empire, which united the Greater Mediterranean Area and Western Europe through a long-running series of military and political campaigns expanding the Roman system of government and Roman values to more underdeveloped areas. Conquered areas became provinces of the empire and Roman military outposts in the provinces became cities with structures designed by the best Roman architects, which hastened the spread of Rome's "modern" way of life while absorbing the traditions and beliefs of these native cultures.[7] Nationalist ideology as well as propaganda supporting the Roman Army and military success, bravery, and valor also strengthened the Roman Empire's spread across Western Europe and the Mediterranean Area.[8] The Roman Empire's well-built aqueducts and cities and sturdy, effective naval fleets, ships and an organized system of paved roads also facilitated fast, easy travel and better networking and trade with neighboring nations and the provinces.[9]

During the Han dynasty under Han Wudi (141–87 BCE), the Chinese government united and became powerful enough that China began to successfully indulge in imperialistic endeavors with its neighboring nations in East Asia.[10] Han China's imperialism was a peaceful tributary system, which focused mainly on diplomatic and trade relations.[11] The growth of the Han Empire facilitated trade and cultural exchange with virtually all of the known world as reached from Asia, and Chinese silks spread through Asia and Inner Asia and even to Rome.[12] The early T'ang dynasty saw China as even more responsive to foreign influence and the T'ang dynasty becoming a great empire.[13] Overseas trade with India and the Middle East grew rapidly, and China's East and Southern Coasts, once distant and unimportant regions, gradually became chief areas of foreign trade.[14] During the Song Dynasty China's navy became more powerful thanks to technological improvements in shipbuilding and navigation, and China's maritime commerce also increased exponentially.[15]

China's power began to decline in the 16th century when the rulers of the subsequent Ming Dynasty neglected the importance of China's trade from sea power. The Ming rulers let China's naval dominance and its grip on the Spice trade slacken, and the European powers stepped in. Portugal, with its technological advances in naval architecture, weaponry, seamanship and navigation, took over the Spice Trade and subdued China's navy. With this, European Imperialism and the age of European Hegemony was beginning, although China still retained power of many of its areas of trade.[16]

Changes in trade systems

One of the most significant differences between proto-globalization and archaic globalization was the switch from inter-nation trading of rarities to the trading of commodities. During the 12th and 13th centuries it was common to trade items that were foreign and rare to different cultures. A popular trade during archaic globalization involved European merchants sailing to areas of India or China in order to purchase luxury items such as porcelain, silk and spices. Traders of the pre-modern period also traded drugs and certain foods such as sugar cane and other crops.[17] While these items were not rarities as such, the drugs and food traded were valued for the health and function of the human body. It was more common during proto-globalization to trade various commodities such as cotton, rice and tobacco.[17] The shift into proto-globalization trade signified the "emergence of the modern international order" and the development of early capitalist expansion which began in the Atlantic during the 17th century and spread throughout the world by 1830.[18]

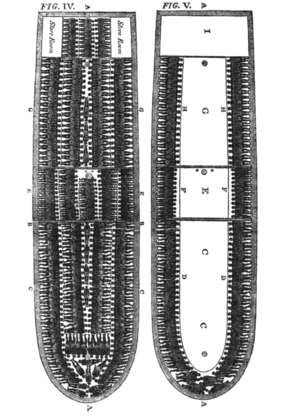

Atlantic slave trade

One of the main reasons for the rise of commodities was the rise in the slave trade, specifically the Atlantic slave trade.

The use of slaves prior to the 15th century was only a minor practice in the labor force and was not crucial in the development of products and goods; but, due to labor shortage, the use of slaves rose.[19] After 1500, the settlement of island despots and plantation centers in Sao Tome began trade relations with the Kingdom of the Kongo, which brought West Central Africa into the Atlantic Slave Trade.[20] The Portuguese maintained an export of slaves from Agadir, an Atlantic port, which they maintained for most of the early 16th century.[21] Also the Portuguese settlement of the Brazilian subcontinent allowed the opening of the American slave market and slaves were shipped from Sao Tome directly to America.[20] The Europeans also took use of the Atlantic Slave Trade in the first half of the century. The European slave ships took their slaves to the Iberian Peninsula, however slave owners in Europe were only seen in wealthy, aristocrat families due to the high costs of slaves and the cheap peasant labor available for agricultural uses, and as its name implies the first use of the African-American slaves in plantation work arose in the Atlantic islands not in the continental Europe.[22] Approximately 10.2 million Africans survived the Atlantic crossing between 1450 and 1870.[23] The large slave population thrived due to the demand for production from the Europeans who found it cheaper to import crops and goods rather than produce them on their own.[24]

Many wars were fought during the 17th century between the slave trading companies for areas that were economically dependent on slaves. The West India Company gained many slaves through these wars (specifically with Portugal) by captains who had captured enemy ships; between 1623 and 1637, 2,336 were captured and sold in the New World by the West India Company.[25] The selling of slaves to the New World opened up trading posts in North America; the Dutch opened their first on Manhattan Island in 1613.[25] The West India Company had also opened a trading post in the Caribbean and the company was also carrying slaves to a colony of New Netherland.[25] The use of slaves had many benefits to the economies and productions in the areas of trade. The emergent rise of coffee, tea, and chocolate in Europe led to the demand for the production of sugar; 70 percent of slaves were used solely for the labor-intensive production of crop.[26] Slave trade was also beneficial to the trade voyages, because the constant sailing allowed investors to buy small shares of many ships at the same time.[27] Hopkin states that many scholars, him among them, argue that slave trade was essential to the wealth of many nations, during and after proto-globalization, and without the trade production would have plummeted.[3] The investment in ships and nautical technology was the catalyst to the complex trade networks developed throughout proto-globalization and into modern globalization.[17]

Plantation economy

Consequently, the rise of slavery was due to the increasing rise of crops being produced and traded, more specifically the rise of the plantation economy The rise of the plantations was the main reason for the trade of commodities during proto-globalization. Plantations were used by the exporting countries (mainly America) to grow the raw materials needed to manufacture the goods which were traded back into the plantation economy.[28] Commodities that grew in trade due to the plantation economy were mainly tobacco, cotton, sugar cane, and rubber.[28]

Tobacco

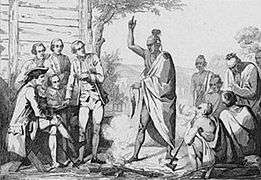

During the second half of the 16th century, Europeans' interest in the New World revolved around gold and silver and not tobacco. The European lack of interest in tobacco was due to the fact that the Amerindians controlled the tobacco industry; as long as the Amerindians controlled the supply there was no need for the incorporation in European commercial capitalism.[29]

The trading of tobacco was a new commodity and was in high popular demand in the 17th century due to the rise of the plantations. Tobacco began to be used a monetary standard, which is why the term "cash crop" was originated.[28] The first export of tobacco from the then-colonies of the United States (specifically Virginia) to London showed fortunes in the English enterprise and by 1627, the Virginia tobacco was being shipped to London at 500,000 pounds a shipment.[30] By 1637, tobacco had become the colony's currency and by 1639 Maryland was exporting 100,000 pounds of tobacco to London.[31] English success with the production of tobacco caught the attention of many Europeans, specifically those colonized on Martinique and Guadeloupe, French islands. These islands soon became wealthy due to the tobacco production and by 1671 roughly one-third of the acreage devoted to the cash crops grown for the islands were for tobacco.[32] While the cultivation of tobacco thrived, production saw severe depressions in later years due to the profits made from sugar. According to an account of the Barbadian exports 82 percent of the island's export value was due to sugar and less than one percent was accounted for by tobacco.[33]

Sugar cane

Another commodity that was a prominent source of trade was the production of sugar from the crop sugar cane. The original habitat of sugar was in India, where it was taken and planted in various islands. Once reaching to the people of the Iberian Peninsula, it was further migrated across the Atlantic Ocean. In the 16th century, the first plantations of sugar were started in the New World, marking the last great stage of migration of the cane to the West.[34] Because of the conflict of transporting sugar in its raw form, sugar was not associated with commerce until the act of refining it came into play; this act became the center for industry. Venice was the center for refining during the Middle Ages, therefore making them the chief traders of sugar. Although, the Spanish and Portuguese held the monopolies of the sugar cane fields in America, they were being supplied by Venice. In the 17th century, England dominated Venice and became the center for refining and cultivating sugar; this leadership was maintained until the rise of French industry.[35] Sugar throughout the 17th century was still considered a luxury until the latter half of the 17th century when the sugar was being produced in mass quantities making it available to the mass of the English people.[36] This turn of events made the sugar a commodity, because the crop was not being used in only special occasion, but in all daily meals.

Hostilities, war, and imperialism

Proto-globalization differed from modern globalization in the practices of expansionism, methods of managing global trade, finances, as well as commercial innovation. With the shift of expansionism by large nations to Western Europe, nations began competing in an effort to achieve world domination. The rise of larger-scale conflicts between these powerful nations over expanding their wealth led to nations taking control over one another's territory and then moving products and the accumulated wealth of these conquered regions back to the sovereign country. Although conflicts occurred throughout the world between 1600 and 1800, European powers found themselves far more equipped to handle the pressures of war. A quote by Christopher Alan Bayly gives a better interpretation of these advantages by stating, "Europeans became much better at killing people. The European ideological wars of the 17th century had created links between war, finance, and commercial innovation which extended all these gains. It gave the Continent a brute advantage in world conflicts which broke out in the 18th century. Western European warfare was peculiarly complicated and expensive, partly because it was amphibious."[37] These battle-tested nations fought for their own needs, but in reality their success increased European advancement in the global market. Each of the following sections will shed light on the history of several key engagements. Whether a war was religious or commercial, its impact was greatly felt throughout the world. British victories during the Anglo-Dutch Wars led to their dominance in commercial shipping and naval power. The stage was set for future conflicts between Britain and foreign nations, as well as domestic frustration with “the motherland” on the North American continent. The French and Indian War, fought between the European powers of France and England, led to a British victory and resulted in continued dominance in maritime enterprise. The American Revolutionary War marked the beginning of the power shift for control over foreign markets.

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a battle over not only religious and political beliefs, but also economic and social as well. This war was between Parliamentarians and Royalists and took place from 1642 to 1651, but was broken into several separate engagements. Charles I and his supporters experienced the first two periods of the war, which resulted in King Charles I dissolving Parliament, which would not be called into session again for over ten years. Reasons for this dismissal were because supporters of Long Parliament tried to install two resolutions into English law. One called for consequences against individuals that taxed without the consent of Parliament and labeled them as enemies of England, while the other stated that innovations in religion would result in the same tag. Each of these policies was aimed at Charles I, in that he was inferior leader as well as a supporter of Catholicism. This prompted the Puritan Revolt and eventually led to the trial and execution of Charles I for treason. The final stage of the English Civil War came in 1649, and lasted until 1651. This time, King Charles II, the son of Charles I led supporters against Parliament. The Battle of Worcester, which took place in 1651, marked the end of the English Civil War. Charles II and other royalist forces were defeated by Parliamentarians and their leader Oliver Cromwell. This war began to take England in different directions regarding religious and political beliefs as well as economic and social. Also, the war constitutionally established that no British monarch was permitted to rule without first having been approved by Parliament.

Anglo-Dutch War

(Jan_Abrahamsz._Beerstraten).jpg)

The Anglo-Dutch War was a naval conflict between England and the Dutch Republic from 1652 to 1654 and was over the competition in commercial maritime and was focused mainly in the East Indies.[38] The first Navigation Act, which forbade the import of goods unless they were transported either in English vessels or by vessels from the country of origin.[38] This was a policy aimed against the Dutch, and fighting broke out on May 19, 1652 with a small skirmish between Dutch and English fleets.[38] The War officially began in July and fighting continued for two years. The Battle of Scheveningen which is also referred to as Texel was the end of serious fighting in the war and took place in July 1653.[39] The Treaty of Westminster was signed in April 1654 ending the war and obligated the Dutch Republic to respect the Navigation Act as well as compensate England for the war.[39]

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War was between the nations of Great Britain and France, along with the numerous Native American Nations allied with both.[40] The French and Indian war was the North American theater of the Seven Years' War being fought in Europe at the time. Growing population in British territory throughout North America forced expansion west; however, this was met with resistance from the French and their Native American allies.[40] French forces began entering British territory, building numerous forts in preparation to defend the newly acquired land. The beginning of the war favored the French and their Native American allies, who were able to defeat British forces time and again, and it was not until 1756 that the British were able to hold off their opposition. Pittsburgh was a center for fighting during the French and Indian War, namely because of the geographical location at the center where three rivers unite: the Allegheny, the Monongahela and the Ohio. The location of present-day Pittsburgh provided an advantage in naval control. Ownership of this point provided not only naval dominance, but it also expanded economic ventures, enabling shipments to be sent and received with relative ease. French and British forces both claimed ownership to this region; the French installing Fort Duquesne and the British with Fort Pitt. Fort Pitt was established in 1758 after French forces abandoned and destroyed Fort Duquesne.[41] The French and Indian War came to an end in 1763, after British forces were able to secure Quebec and Montreal from the French and on February 10, the Treaty of Paris was signed.[40] The French were forced to surrender their territory in North America, giving England control all the way to the Mississippi River. The effects of this war were heavily felt in the North American British colonies. England imposed many taxes on colonists in order to control the newly acquired territory. These tensions would soon culminate into a war for independence as well as a shift in power for dominance in the economic world.

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War was a war between the nation of England and the 13 colonies in the North American continent. This war lasted from 1775 to 1783 and began with the Battle of Bunker Hill, where over 1,150 British soldiers were killed or wounded. This equated to almost half of the entire British army that were present at the engagement. American casualties were far less severe, totaling an estimated at 450 killed and wounded. The British, however, were able to take the ground and push the newly formed Continental Army back to the city of Boston, which also soon fell to British forces. Before the Battle of Bunker Hill, the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April, 1775, saw British troops begin their assault into the American colonies. British troops were searching for colonist supply depots, however, were met by heavy resistance and the British forces were turned around at Concord by outnumbering Minutemen forces. On July 4, 1776 the Declaration of Independence was signed by the Second Continental Congress and officially declared the colonies of North America to be a sovereign nation, free from England's rule. Also, the Congress permitted funding for a Continental Army, which is the first instance of an American political body handling military affairs. The British were dominating in the beginning of the war, holding off Continental regulars and militia and gaining vast amounts of territory throughout North America. However, the tide began to turn for the colonists in 1777 with their first major victory over British forces at the Battle of Saratoga. Victory for the rest of the war pushed back and forth between the British and colonists, but the alliance with France in 1778 by the American colonists leveled the playing field and aided in the final push for the defeat of the British Army and Navy. In 1781, American and French forces were able to trap the escaping southern British Army at Yorktown, thus ending the major fighting of the Revolution. The Treaty of Paris was signed in 1783, and recognized the American colonies as an independent nation. The newly formed United States would undergo numerous transitions to becoming one of the top economic and military powers in the world.

Treaties and agreements

Much of the trading during the proto-globalization time period was regulated by Europe. Globalization from an economic standpoint relied on the East India Company. The East India Company was a number of enterprises formed in western Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, initially created to further trade in the East Indies. The company controlled trading from India to East and Southeast Asia.[42]

One of the key contributors to globalization was the Triangular Trade and how it connected the world. The Triangular Trade or Triangle Trade was a system used to connect three areas of the world through trade.[43] Once traded, items and goods were shipped to other parts of the world, making the triangle trade a key to global trade. The Triangle Trade system was run by Europeans, increasing their global power.[43]

Europeans would sail to the West African coast and trade African kings manufactured goods (rifles and ammunition) for slave.[43] From there slaves would be sent to the West Indies or the east coast of North America to be used for labor. Goods such as cotton, molasses, sugar, tobacco would be sent from these places back to Europe.[43] Europe would also use their goods and trade with Asian countries for tea, cloth and spices.[43] The triangle trade in a sense was an agreement for established trade routes, that led to greater global integration, which ultimately contributed to globalization.[23]

Along with the control Europe gained, as far as global trade, came several treaties and laws. In 1773, the Regulating Act was passed, regulating affairs of the company in India and London.[44] In 1748, the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle ended the War of the Austrian Succession, but failed to settle the commercial struggle between England and France in the West Indies, Africa and India.[45] The treaty was an attempt at regulating trade and market expansion between the two regions, but was ultimately unsuccessful.

Globalization at this time was hindered by war, diseases and population growth in certain areas.[46] The Corn Laws were established to regulate imports and exports of grains in England, thus restricting trade and the expansion of globalization.[47] The Corn Crop Laws hindered the market economy and globalization based on tariffs and import restrictions.[47] Eventually, the Ricardian theory of economics became prominent and allowed for improved trade regulations, specifically with Portugal.[48]

Transition into modern globalization

According to Sebastian Conrad, proto-globalization is marked with a “rise of national chauvinism, racism, Social Darwinism, and genocidal thinking” which came to be with relations to the “establishment of a world economy”.[49] Beginning in the 1870s, the global trade cycle started to cement itself so that more nations' economies depended on one another than in any previous era. Domino effects in this new world trade cycle lead to both worldwide recessions and world economic booms.[49] Modelski describes the late period of proto-globalization as a "thick range of global networks extending throughout the world at high speed and covering all components of society".[50] By the 1750s, Europe, Africa, Asia, and America's contact had grown into a stable multilateral interdependency which was echoed in the modern globalization period.[51]

Shift in capital

Although the North Atlantic World dominated the global system before proto-globalization, a more "multipolar global economy" started taking form around the early 19th century, and capital was becoming highly mobile.[52] By the end of the 19th century, British capital wealth was 17% overseas,[53] and the level of capital invested overseas nearly doubled by 1913 to 33%.[53] Germany invested one-fifth of their total domestic savings in 1880, and, like Britain, increased their wealth tremendously in the early 20th century.[53] The net foreign investment of total domestic savings abroad was 35% in 1860, 47% in 1880, and 53% in the years prior to the Great War.[53] Global investments were taking a steady rise throughout societies, and those able to invest thrust more and more of their domestic savings into international investments.

The ability to mobilize capital was due to the development of the Industrial Revolution and the beginnings of mechanical production (most prominent in Great Britain).[54] During proto-globalization, "merchant capitalists in many societies quickly became aware of potential markets and new producers and began to link them together in new patterns of world trade.[55] The expansion of the slave production and the exploitation of the Americas put Europeans on the top of the economic network.[56] During the modern globalization period, mass production allowed the development of a stronger, more complex global network of trade. Another element of European success between 1750 and 1850 was the limitation and "relative 'failure'" of the Afro-Asian Industrial Revolution.[57] The movement into modern globalization was marked with the economic drain of capital into Europe.[58]

Shift in culture

Like capital, the end of proto-globalization was filled with mobility of individuals. The time of proto-globalization was one filled with “mutual influence, hybridization, and cross-cultural entanglement”.[59] Many historians blame this web of national entanglements and agreements as the cause for the intensity and vast involvement during World War I. Between 1750–1880, the expansion of worldwide integration was influenced by the new capacities in production, transportation, and communication.[51] The end of proto-globalization also marked the final phase of "great domestication".[54] After the 1650s, the process of regular and intensive agrarian exploitation was complete.[54] Human population began to increase almost exponentially with the end of the great pandemics.[54] At the end of the proto-globalization and the cusp of modern globalization, population began to "recover in Central and South America," where at the beginning of proto-globalization, European-imported illnesses had savagely decreased indigenous populations.[54] The importation of nutritious varieties from Central and South America created a more fertile and resilient population to forge ahead into modern globalization.[54] The greater population pushed individuals in high populated areas to "spill into less populous forested and grazing lands, and bring them under cultivation".[54] This development lead to an influx in produce production and exported trade.

Another development that lead to the shift to modern globalization was the development of a more politicized system.[60] Proto-globalization period marked a steady expansion of larger states from the Indonesian islands to northern Scandinava.[61] The settlement of these individuals made it easier for governments to tax, develop an army, labor force, and create a sustainable economy.[61] The development and streamlining of these cultural aspects lead to an increase in peripheral players in the game of globalization.[61] The stable legal institutions developed in the late proto-globalization and early modern globalization period established economic advances, intellectual property rights (more predominantly in England), general geographical stability, and generational societal improvement.[62]

The shift in exchange of technological advancements was another reason for modern globalization. In the early 19th century, European civilizations traveled the world to accumulate an "impressive knowledge about languages, religions, customs, and political orders of other countries.[63] By the end of the 19th century, Europe was no longer receiving any significant technological innovations from Asia.[63]

Shift in global networks

The developed global networks lead to the creation of new networks leading to new production.[64] By 1880, there was a renewed thrust of European colonial expansion.[65] The shift to modern globalization was slow, overlapping and interacting. Mid-19th century, noncompeting goods were exchanged between continents and markets for widely used commodities developed.[65] Also, labor was becoming globally integrated.[65] Modern globalization came to be as the movement of general expansion of socio-economic networks became more elaborate. An example of this is the development and establishment of free masonry.[66] The "existing trading networks grew, capital and commodity flows intensified.[67] The permanence of long-term interdependencies was unchanged.[64] By the beginning of the modern globalization period, the European colonial expansion retreats into itself. National societies began to regret the economic integration and attempted to limit the effects.[68] Bayly, Hopkins and others stress that proto-globalization's transformation into modern globalization was a complex process that took place at different times in different regions,and involved the hold-over of older notions of value and rarity which had their origins in the pre-modern period. Thus leading to the age of economic deglobalization and world wars which ended after 1945.[68]

See also

- Age of Exploration

- Archaic globalization

- Early Modern Period

- Geography and cartography in medieval Islam

- History of globalization

- Military globalization

- World Systems Theory

References

Notes

- Hopkins 2003, p. 3.

- Hopkins 2003, pp. 4–5.

- Hopkins 2003, p. 5.

- Hopkins 2003, p. 6.

- Hopkins 2003, p. 7.

- Hopkins 2003, pp. 4–5, 7.

- Shelton 1998, p. 20.

- Dillon & Garland 2005, p. 235.

- Dillon & Garland 2005, pp. 56–58.

- Cohen 2000, pp. 58–59.

- Cohen 2000, p. 60.

- Cohen 2000, pp. 61–62.

- Fairbank, Reischauer & Craig 1973, p. 111.

- Fairbank, Reischauer & Craig 1973, pp. 135–36.

- Fairbank, Reischauer & Craig 1973, p. 135.

- Fairbank, Reischauer & Craig 1973, pp. 181–83.

- Hopkins 2003, pp. 4.

- Bayly 2004, p. 15.

- Klein 1999, p. 2.

- Klein 1999, p. 9.

- Thomas 1997, p. 107.

- Klein 1999, p. 20.

- Osterhammel & Petersson 2005, p. 50.

- Solow 1991, p. 5.

- Thomas 1997, p. 170.

- Thomas 1997, p. 189.

- Daudin 2002.

- "Tobacco in Virginia". Retrieved 2009-11-11.

- Goodman 1993, p. 129.

- Gately 2001, p. 72.

- Goodman 1993, p. 136.

- Goodman 1993, p. 137.

- Goodman 1993, p. 140.

- Ellis 1905, p. 4.

- Ellis 1905, p. 5.

- Ellis 1905, p. 6.

- Bayly 2004, p. 64.

- "First Anglo-Dutch War, (1652–1654)". Historyofwar.org. Retrieved 2013-11-15.

- Dutch and English fleets numbering over one hundred ships fought for twelve hours resulting in over 1,600 men killed, including Admiral Tromp for the Dutch and only half that number for the English.

- Schwartz 1999.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2009-12-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "East India Company". 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "Slaves". 2001. Archived from the original on 2009-11-24. Retrieved 2009-11-16.

- "Regulating Act 2009". Retrieved 2009-11-13.

- "Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- "Why globalisation might have started in the eighteenth century". May 16, 2008. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- Lusztig 1995, pp. 394–396.

- "International Trade". 2009. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- Conrad 2007, p. 4.

- Modelski, Devezas & Thompson 2008, p. 12.

- Osterhammel & Petersson 2005, p. 28.

- Conrad 2007, p. 5.

- O'Rourke & Williamson 1999, p. 208.

- Bayly 2004, p. 49.

- Bayly 2004, p. 53.

- Bayly 2004, pp. 53–55.

- Bayly 2004, p. 56.

- Bayly 2004, p. 57.

- Conrad 2007, p. 6.

- Osterhammel & Petersson 2005, p. 208.

- Bayly 2004, p. 50.

- Bayly 2004, p. 61.

- Osterhammel & Petersson 2005, p. 52.

- Modelski, Devezas & Thompson 2008, p. 248.

- Osterhammel & Petersson 2005, p. 16.

- Harland-Jacobs 2007, p. 24.

- Harland-Jacobs 2007, p. 4.

- Osterhammel & Petersson 2005, p. 29.

Sources

- Bayly, C. A. (2004). The Birth of the Modern World: Global Connections and Comparisons, 1780–1914. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. ISBN 0-631-18799-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohen, Warren I. (2000). East Asia at the Center: Four Thousand Years of Engagement With the World. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10109-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conrad, Sebastian (2007). Competing Visions of World Order Global Moments and Movements, 1880s–1930s. Palgrave Macmillan Series in Transnational History. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-403-97988-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Daudin, Guillaume (2002). "The quality of slave trade investment in eighteenth century France" (PDF). Documents de Travail de l'OFCE, No 2002-06. Paris: OFCE. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-09-01. Retrieved 2013-11-15.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dillon, Matthew; Garland, Lynda (2005). Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook: From the early Republic to the assassination of Julius Caesar. Abingdon and New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22458-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ellis, Ellen Deborah (1905). An Introduction to the History of Sugar as a Commodity. Philadelphia, PA: John C. Winston Co. OL 7045412M.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fairbank, John K.; Reischauer, Edwin O.; Craig, Albert M. (1973). East Asia: Tradition and Transformation. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-395-14525-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gately, Iain (2001). Tobacco: A Cultural History of How an Exotic Plant Seduced Civilization. New York, NY: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-802-11705-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goodman, Jordan (1993). Tobacco in History: The Cultures of Dependence. London and New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-04963-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harland-Jacobs, Jessica L. (2007). Builders of Empire: Freemasons and British Imperialism, 1717–1927. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-807-83088-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hopkins, A. G., ed. (2003). Globalization in World History. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-97942-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Klein, Herbert S. (1999). The Atlantic Slave Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-46020-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lusztig, Michael (1995). "Solving Peel's Puzzle: Repeal of the Corn Laws and Institutional Preservation". Comparative Politics. 27 (4): 393–408. doi:10.2307/422226. JSTOR 422226.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Modelski, George; Devezas, Tessaleno Devezas; Thompson, William R., eds. (2008). Globalization as Evolutionary Process: Modeling Global Change. Rethinking Globalizations. Abingdon and New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-77360-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Osterhammel, Jürgen; Petersson, Niels P. (2005). Globalization: A Short History. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12165-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Rourke, Kevin H.; Williamson, Jeffrey G. (1999). Globalization and History The Evolution of a Nineteenth-Century Atlantic Economy. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-15049-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schwartz, Seymour I. (1999). French and Indian War, 1754–1763: The Imperial Struggle for North America. Edison, NJ: Castle Books. ISBN 978-0-785-81165-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sharp, Paul. "Why Globalization Might Have Started in the Eighteenth Century""VoxEU", May 16, 2008, Accessed November 2009

- Shelton, Jo-Ann (1998). As The Romans Did: A Sourcebook in Roman Social History (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-195-08974-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Solow, Barbara L. (1991). Slavery and the Rise of the Atlantic System. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40090-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, Hugh (1997). The Slave Trade: The History Of The Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440–1870. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-81063-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- A Quick Guide to the World History of Globalization, http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~dludden/global1.htm

- Bakerova, Katarina. "Slaves" "African Cultural Center", California, 1991.

- "Corn Laws" "Encyclopædia Britannica"

- "East India Company" "Encyclopædia Britannica"

- "Regulating Act" "Encyclopædia Britannica"

- "International Trade" "Encyclopædia Britannica"

- "Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle" "Encyclopædia Britannica"