Decline in insect populations

Several studies report a substantial decline in insect populations. Most commonly, the declines involve reductions in abundance, though in some cases entire species are going extinct. The declines are far from uniform. In some localities, there have been reports of increases in overall insect population, and some types of insects appear to be increasing in abundance across the world. A 2020 meta-analysis published in the journal Science found that globally, terrestrial insects appeared to be declining in abundance at a rate of about 9% per decade, while the abundance of freshwater insects has increased by 11% per decade.

Some of the insects most affected include bees, butterflies, moths, beetles, dragonflies and damselflies. Anecdotal evidence has been offered of much greater apparent abundance of insects in the 20th century; recollections of the windscreen phenomenon are an example.[2]

Possible causes of the decline have been identified as habitat destruction, including intensive agriculture, the use of pesticides (particularly insecticides), urbanization, and industrialization; introduced species; and climate change.[3] Not all insect orders are affected in the same way; many groups are the subject of limited research, and comparative figures from earlier decades are often not available. The decline of the scientific field of entomology may also be contributing to errors in data analysis and overgeneralization from limited findings, resulting in exaggeration of the decline in insect populations.

In response to the reported declines, increased insect related conservation measures have been launched. In 2018 the German government initiated an "Action Programme for Insect Protection",[4][5] and in 2019 a group of 27 British entomologists and ecologists wrote an open letter calling on the research establishment in the UK "to enable intensive investigation of the real threat of ecological disruption caused by insect declines without delay". [6]

History

The fossil record concerning insects stretches back hundreds of millions of years. It suggests there are ongoing background levels of both new species appearing and extinctions. Very occasionally, the record also appears to show mass extinctions of insects, understood to be caused by natural phenomena such as volcanic activity or meteor impact. The Permian–Triassic extinction event saw the greatest level of insect extinction, and the Cretaceous–Paleogene the second highest. Insect diversity has recovered after mass extinctions, as a result of periods in which new species originate with increased frequency, although the recovery can take millions of years.[7]

Concern about a human-caused Holocene extinction has been growing since the late 20th century, although much of the early concern was not focused on insects. In a report on the world's invertebrates, the Zoological Society of London suggested in 2012 that insect populations were in decline globally, affecting pollination and food supplies for other animals.[8][9][10][11] It estimated that about 20 percent of all invertebrate species were threatened with extinction, and that species with the least mobility and smallest ranges were most at risk.[8]

Studies finding insect decline have been available for decades—one study tracked a decline from 1840 to 2013—but it was the 2017 re-publication of the German nature reserves study[1] that saw the issue receive widespread attention in the media.[12][10] The press reported the decline with alarming headlines, including "Insect Apocalypse".[11][13] Ecologist Dave Goulson told The Guardian in 2017: "We appear to be making vast tracts of land inhospitable to most forms of life, and are currently on course for ecological Armageddon."[14] For many studies, factors such as abundance, biomass, and species richness are often found to be declining for some, but not all locations; some species are in decline while others are not.[15] The insects studied have mostly been butterflies and moths, bees, beetles, dragonflies, damselflies and stoneflies. Every species is affected in different ways by changes in the environment, and it cannot be inferred that there is a consistent decrease across different insect groups. When conditions change, some species adapt easily to the change while others struggle to survive.[16]

A March 2019 statement by the Entomological Society of America said there was not yet sufficient data to predict an imminent mass extinction of insects and that some of the extrapolated predictions might "have been extended well past the limits of the data or have been otherwise over-hyped".[17] For some insect groups such as some butterflies, bees, and beetles, declines in abundance and diversity have been documented in European studies. Other areas have shown increases in some insect species, although trends in most regions are currently unknown. It is difficult to assess long-term trends in insect abundance or diversity because historical measurements are generally not known for many species. Robust data to assess at-risk areas or species is especially lacking for arctic and tropical regions and a majority of the southern hemisphere.[17]

Causes and consequences

Suggested causes

The decline has been attributed to habitat destruction caused by intensive farming and urbanisation,[18][19][3] pesticide use,[20] introduced species,[21][3] climate change,[3] and artificial lighting.[22][23] The use of increased quantities of insecticides and herbicides on crops have affected not only non-target insect species, but also the plants on which they feed. Climate change and the introduction of exotic species that compete with the indigenous ones put the native species under stress, and as a result they are more likely to succumb to pathogens and parasites.[16] Plants grow faster in presence of increased CO2 but the resulting plant biomass contains fewer nutrients.[24] While some species such as flies and cockroaches might increase as a result,[3] the total biomass of insects is estimated to be decreasing by between about 0.9 to 2.5% per year.[25][26]

Effects

Insect population decline affects ecosystems, and other animal populations, including humans. Insects are at "the structural and functional base of many of the world's ecosystems."[3] A 2019 global review warned that, if not mitigated by decisive action, the decline would have a catastrophic impact on the planet's ecosystems.[3] Birds and larger mammals that eat insects can be directly affected by the decline. Declining insect populations can reduce the ecosystem services provided by beneficial bugs, such as pollination of agricultural crops, and biological waste disposal.[25] According to the Zoological Society of London, in addition to such loss of instrumental value, the decline also represents a loss of the declining species' intrinsic value.[8]

Evidence

Metrics

Three principal metrics are used to capture and report on insect declines:

- Abundance- simply put the numerical total of individual insects. Depending on context, it can refer to the number of insects in a particular assembly, in a geographical area, or the sum total of insects globally (regardless of which species the individuals belong to).

- Biomass - the total weight of insects (again regardless of species).

- Biodiversity - the number of extant insect species. Depending on context, a reduction in biodiversity can mean certain species of insects have vanished locally, though it may mean species have gone totally extinct across the entire planet. [27][26][3]

Most of the individual studies tracking insect declines report just abundance, others just on biomass, some on both, and yet others report on all three metrics. Data directly related to diversity loss at global level is more sparse than for abundance or biomass declines. Estimates for diversity loss at a planetary level tend to involve extrapolating from abundance or biomass data; while studies sometimes show local extirpation of an insect species, actual world wide extinctions are challenging to discern. In a 2019 review, David Wagner noted that currently the Holocene extinction is seeing animal species loss at about 100 - 1,000 times the planet's normal background rate, and that various studies found a similar, or possibly even faster extinction rate for insects. Wagner opines that serious though this biodiversity loss is, it is the decline in abundance that will have the most serious ecological impact.[27][26][3] [28]

Relationship between decline metrics

In theory it is possible for the three metrics to be independent. E.g. a decline in biomass might not involve a decrease in abundance or diversity if all that was happening was that typical insects were getting smaller. In practice though, abundance & biomass tend to be closely related, typically showing a similar level of decline. Change in biodiversity is often, though not always, [note 1] directly proportional to the other two metrics. [26][3]

Rothamsted Insect Survey, UK

The Rothamsted Insect Survey at Rothamsted Research, Harpenden, England, began monitoring insect suction traps across the UK in 1964. According to the group, these have produced "the most comprehensive standardised long-term data on insects in the world".[30] The traps are "effectively upside-down Hoovers running 24/7, continually sampling the air for migrating insects," according to James Bell, the survey leader, in an interview in 2017 with the journal Science. Between 1970 and 2002, the insect biomass caught in the traps declined by over two-thirds in southern Scotland, although it remained stable in England. The scientists speculate that insect abundance was already lost in England by 1970 (figures in Scotland were higher than in England when the survey began), or that aphids and other pests increased there in the absence of their insect predators.[2]

Dirzo et al. 2014

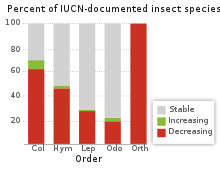

A 2014 review by Rodolfo Dirzo and others in Science noted: "Of all insects with IUCN-documented population trends [203 insect species in five orders], 33% are declining, with strong variation among orders." In the UK, "30 to 60% of species per order have declining ranges". Insect pollinators, "needed for 75% of all the world's food crops", appear to be "strongly declining globally in both abundance and diversity", which has been linked in Northern Europe to the decline of plant species that rely on them. The study referred to the human-caused loss of vertebrates and invertebrates as the "Anthropocene defaunation".[28][13][11]

Krefeld study, Germany

In 2013 the Krefeld Entomological Society reported a "huge reduction in the biomass of insects"[12] caught in malaise traps in 63 nature reserves in Germany (57 in Nordrhein-Westfalen, one in Rheinland-Pfalz and one in Brandenburg).[31][32] A reanalysis published in 2017 suggested that, in 1989–2016, there had been a "seasonal decline of 76%, and mid-summer decline of 82%, in flying insect biomass over the 27 years of study". The decline was "apparent regardless of habitat type" and could not be explained by "changes in weather, land use, and habitat characteristics". The authors suggested that not only butterflies, moths and wild bees appear to be in decline, as previous studies indicated, but "the flying insect community as a whole".[1][12][33][34][35][note 2]

According to The Economist, the study was the "third most frequently cited scientific study (of all kinds) in the media in 2017".[note 3] The British entomologist Simon Leather said that he hoped media reports, following the study, of an "ecological Armageddon" had been exaggerated; he argued that the Krefeld and other studies should be a wake-up call, and that more funding is needed to support long-term studies.[12][14][37] The Krefeld study's authors were not able to link the decline to climate change or pesticides, he wrote, but they suggested that intensive farming was involved. While agreeing with their conclusions, he cautioned that "the data are based on biomass, not species, and the sites were not sampled continuously and are not globally representative".[note 4] As a result of the Krefeld and other studies, the German government established an "Action Programme for Insect Protection".[4]

El Yunque National Forest, Puerto Rico

A 2018 study of the El Yunque National Forest in Puerto Rico reported a decline in arthropods, and in lizards, frogs, and birds (insect-eating species) based on measurements in 1976 and 2012.[38][3] The American entomologist David Wagner called the study a "clarion call" and "one of the most disturbing articles" he had ever read.[39] The researchers reported "biomass losses between 98% and 78% for ground-foraging and canopy-dwelling arthropods over a 36-year period, with respective annual losses between 2.7% and 2.2%".[3] The decline was attributed to a rise in the average temperature; tropical insect species cannot tolerate a wide range of temperatures.[38][3][25] The lead author, Brad Lister, told The Economist that the researchers were shocked by the results: "We couldn’t believe the first results. I remember [in the 1970s] butterflies everywhere after rain. On the first day back [in 2012], I saw hardly any."[36]

Netherlands and Switzerland

In 2019 a study by Statistics Netherlands and the Vlinderstichting (Dutch Butterfly Conservation) of butterfly numbers in the Netherlands from 1890 to 2017 reported an estimated decline of 84 percent. When analysed by type of habitat, the trend was found to have stabilised in grassland and woodland in recent decades but the decline continued in heathland. The decline was attributed to changes in land use due to more efficient farming methods, which has caused a decline in weeds. The recent up-tick in some populations documented in the study was attributed to (conservationist) changes in land management and thus an increase in suitable habitat.[40][41][42][43] A report by the Swiss Academy of Natural Sciences in April 2019 reported that 60 percent of the insects that had been studied in Switzerland were at risk, mostly in farming and aquatic areas; that there had been a 60 percent decline in insect-eating birds since 1990 in rural areas; and that urgent action was needed to address the causes.[44][45]

2019 Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys review

A 2019 review by Francisco Sánchez-Bayo and Kris A. G. Wyckhuys in the journal Biological Conservation analysed 73 long-term insect surveys that had shown decline, most of them in the United States and Western Europe.[3][46] While noting population increases for certain species of insects in particular areas, the authors reported an annual 2.5% loss of biomass. They wrote that the review "revealed dramatic rates of decline that may lead to the extinction of 40% of the world's insect species over the next few decades",[3][47] a conclusion that was challenged.[48][49] They did note the review's limitations, namely that the studies were largely concentrated on popular insect groups (butterflies and moths, bees, dragonflies and beetles); few had been done on groups as Diptera (flies), Orthoptera (which includes grasshoppers and crickets), and Hemiptera (such as aphids); data from the past from which to calculate trends is largely unavailable; and the data that does exist mostly relates to Western Europe and North America, with the tropics and southern hemisphere (major insect habitats) under-represented.[3][50]

The methodology and strong language of the review were questioned. The keywords used for a database search of the scientific literature were [insect*] and [declin*] + [survey], which mostly returned studies finding declines, not increases.[48][49][51] Sánchez-Bayo responded that two thirds of the reviewed studies had come from outside the database search.[52] David Wagner wrote that many studies have shown "no significant changes in insect numbers or endangerment", despite a reporting bias against "non-significant findings". According to Wagner, the papers' greatest mistake was to equate "40% geographic or population declines from small countries with high human densities and about half or more of their land in agriculture to 'the extinction of 40% of the world's insect species over the next few decades'." He wrote that 40 percent extinction would amount to the loss of around 2.8 million species, while fewer than 100 insect species are known to have become extinct. While it is true that insects are declining, he wrote, the review did not provide evidence to support its conclusion.[48] Other criticism included that the authors attributed the decline to particular threats based on the studies they reviewed, even when those studies had simply suggested threats rather than clearly identifying them.[49] The British ecologist Georgina Mace agreed that the review lacked detailed information needed to assess the situation, but said it might underestimate the rate of insect decline in the tropics.[47]

In assessing the study methodology, an editorial in Global Change Biology stated, "An unbiased review of the literature would still find declines, but estimates based on this 'unidirectional' methodology are not credible.[15] Komonen et al. considered the study "alarmist by bad design" due to unsubstantiated claims and methodological issues that undermined credible conservation science. They stated what were called extinctions in the study represented species loss in specific sites or regions, and should not have extrapolated as extinction at a larger geographic scale. They also listed that IUCN Red List categories were misused as insects with no data on a decline trend were classified as having a 30% decline by the study authors.[53] Simmons et al. also had concerns the review's search terms, geographic biases, calculations of extinction rates, and inaccurate assessment of drivers of population change stating while it was "a useful review of insect population declines in North America and Europe, it should not be used as evidence of global insect population trends and threats."[49]

Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services

The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services reported its assessment of global biodiversity in 2019. Its summary for insect life was that "Global trends in insect populations are not known but rapid declines have been well documented in some places. ... Local declines of insect populations such as wild bees and butterflies have often been reported, and insect abundance has declined very rapidly in some places even without large-scale land-use change, but the global extent of such declines is not known. ... The proportion of insect species threatened with extinction is a key uncertainty, but available evidence supports a tentative estimate of 10 per cent."[54]

van Klink et al. 2020

A 2020 meta-analysis by van Klink and others, published in the journal Science, found that globally, since 1990, terrestrial insects appear to be declining in abundance at a rate of about 9% per decade, while the abundance of freshwater insects has increased by 12%. The increase in freshwater insects may in part be due to efforts to clean up lakes and rivers, and may also relate to global warming and enhanced primary productivity driven by increased nutrient inputs. The study analysed 166 long-term studies, involving 1676 different sites across the world. It found considerable variations in insect decline depending on locality – the authors considered this a hopeful sign, as it suggests that local factors, including conservation efforts, can make a big difference.[26]

Crossley et al. 2020

In a 2020 paper that studied insects and other arthropods across all Long-term Ecological Research sites in the U.S., the authors found some declines, some increases, but generally few consistent losses in arthropod abundance or diversity. This study found some variation in location, but generally stable numbers of insects. As noted in the paper, the authors did not do any a priori selection of arthropod taxa. Instead, they tested the hypothesis that if the arthropod decline was pervasive, it would be detected in monitoring programs not originally designed to look for declines. They suggest that overall numbers of insects vary but overall show no net change.[55]

Anecdotal evidence

.jpg)

Anecdotal evidence for insect decline has been offered by those who recall apparently greater insect abundance in the 20th century. Entomologist Simon Leather recalls that, in the 1970s, windows of Yorkshire houses he visited on his early-morning paper round would be "plastered with tiger moths" attracted by the house's lighting during the night. Tiger moths have now largely disappeared from the area.[56] Another anecdote is recalled by environmentalist Michael McCarthy concerning the vanishing of the "moth snowstorms", a relatively common sight in the UK in the 1970s and earlier. Moth snowstorms occurred when moths congregated with such density that they could appear like a blizzard in the beam of automobile headlights.[57] A 2019 survey by Mongabay of 24 entomologists working on six continents found that on a scale of 0 to 10, with 10 being the worst, all the scientists rated the severity of the insect decline crisis as being between 8–10. [58]

The windshield phenomenon – car windscreens covered in dead insects after even a short drive through a rural area in Europe and North America – seems also largely to have disappeared; in the 21st century, drivers find they can go an entire summer without noticing it.[2][59] John Rawlins, head of invertebrate zoology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, speculated in 2006 that more aerodynamic car designs could explain the change.[60] Entomologist Martin Sorg told Science in 2017: "I drive a Land Rover, with the aerodynamics of a refrigerator, and these days it stays clean."[2] Rawlins added that land next to high-speed highways has become more manicured and therefore less attractive to insects.[60] In 2004 the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds organised a Big Bug Count, issuing "splatometers" to about 40,000 volunteers to help count the number of insects colliding with their number plates. They found an average of one insect per 5 miles (8 km), which was less than expected.[59][61]

Reception

Responses

Chris D. Thomas and other scientists warned of the need for "joined-up thinking" in responding to the decline, ideally backed up by more robust data than is available so far. In particular, they warned that excessive focus on reducing pesticide use could be counter productive. Pests already cause a 35 percent yield loss for crops, which can rise to 70 percent when pesticides are not used, they wrote. If the crop shortfall is compensated for by expanding agricultural land with deforestation and other habitat destruction, it could exacerbate insect decline.[15]

In the UK, 27 ecologists and entomologists signed an open letter to The Guardian in March 2019, calling on the British research establishment to investigate the decline. Signatories included Simon Leather, Stuart Reynolds (former president of the Royal Entomological Society), John Krebs and John Lawton (both former presidents of the Natural Environment Research Council), Paul Brakefield, George McGavin, Michael Hassell, Dave Goulson, Richard Harrington (editor of the Royal Entomological Society's magazine, Antenna), Kathy Willis and Jeremy Thomas.[6]

In April 2019, in response to the studies about insect decline, Carol Ann Duffy released several poems, by herself and others, to mark the end of her tenure as Britain's poet laureate and to coincide with protests that month by the environmentalist movement Extinction Rebellion. The poets included Fiona Benson, Imtiaz Dharker, Matthew Hollis, Michael Longley, Daljit Nagra, Alice Oswald, and Denise Riley. Duffy's contribution was "The Human Bee".[62]

Conservation measures

Much of the world's efforts to retain biodiversity at national level is reported to the United Nations as part of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Reports typically describe policies to prevent the loss of diversity generally, such as habitat preservation, rather than specifying measures to protect particular taxa. Pollinators are the main exception to this, with several countries reporting efforts to reduce the decline of their pollinating insects.[4]

Following the 2017 Krefeld and other studies, the German environment ministry, the BMU, started an Action Programme for Insect Protection (Aktionsprogramm Insektenschutz).[4] Their goals include promoting insect habitats in the agricultural landscape, and reducing pesticide use, light pollution, and pollutants in soil and water.[5]

In a 2019 paper, scientists Olivier Dangles and Jérôme Casas listed 100 studies and other references suggesting that insects can help meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) adopted in 2015 by the United Nations. They argued that the global policy-making community should continue its transition from seeing insects as enemies, to the current view of insects as "providers of ecosystem services", and should advance to a view of insects as "solutions for SDGs" (such as using them as food and biological pest control).[63][64]

The Entomological Society of America suggests that people maintain plant diversity in their gardens and leave "natural habitat, like leaf litter and dead wood".[17] The Xerces Society is a US based environmental organization that collaborates with both federal and state agencies, scientists, educators, and citizens to promote invertebrate conservation, applied research, advocacy, public outreach and education. Ongoing projects include the rehabilitation of habitat for endangered species, public education about the importance of native pollinators, and the restoration and protection of watersheds. They have been doing a Western Monarch Thanksgiving Count which includes observations from volunteers for 22 years.[65]

Phone apps such as iNaturalist can be used to photograph and identify specimens; these are used in programs such as the City Nature Challenge. Activities and projects may focus upon a particular type of insect, such as National Moth Week and monarch butterfly conservation in California.[66]

Decline of insect studies

One reason that studies into the decline are limited is that entomology and taxonomy are themselves in decline.[67][68][69] At the 2019 Entomology Congress, leading entomologist Jürgen Gross said that "We are ourselves an endangered species" while Wolfgang Wägele – an expert in systematic zoology – said that "in the universities we have lost nearly all experts".[70] General biology courses in college give less attention to insects, and the number of biologists specialising in entomology is decreasing as specialties such as genetics expand.[71][72][73] In addition, studies investigating the decline tend to be done by collecting insects and killing them in traps, which poses an ethical problem for conservationists.[74][75]

See also

Notes

- Some studies find cases where, in certain locations, change in biodiversity is inversly proportional to the other metrics. For exapmle, a 42 year study of insects in the pristine Breitenbach stream near Schlitz, which is believed to have been unaffected by anthropogenic decline related causes except for climate change, found that while abundance of insects decreased, biodiversity actually rose, especially during the first half of the study. [29]

- Francisco Sánchez-Bayo and Kris A. G. Wyckhuys (Biological Conservation, April 2019): "In 2017, a 27-year long population monitoring study revealed a shocking 76% decline in flying insect biomass at several of Germany's protected areas (Hallmann et al., 2017). This represents an average 2.8% loss in insect biomass per year in habitats subject to rather low levels of human disturbance, which could either be undetectable or regarded statistically non-significant if measurements were carried out over shorter time frames. Worryingly, the study shows a steady declining trend over nearly three decades."[3]

- The Economist (23 March 2019): "The study [Hallmann et al. 2017] was the third most frequently cited scientific study (of all kinds) in the media in 2017 and pushed the governments of Germany and the Netherlands into setting up programmes to protect insect diversity."[36]

- Simon Leather (Annals of Applied Biology, 20 December 2017): "Four years ago a group of German entomologists reported that there had been a huge reduction in the biomass of insects caught using Malaise traps sited in 63 German nature reserves since 1989 (Sorg et al., 2013). This shocking observation went almost unnoticed until a reanalysis of the data appeared recently (Hallmann et al., 2017). The latter paper generated a flurry of media activity and the phrase 'Ecological Armageddon' swiftly circled the globe. Although not denying the decline reported, there are a number of caveats that should be considered when reading the two papers; the data are based on biomass, not species, the sites were not sampled continuously and are not globally representative (Saunders, 2017). The authors of the German study were not able to link the observed decline to climate change or pesticide use; although agricultural intensification and the practices associated with it, were, however, suggested as likely to be involved in some way."[12]

References

- Hallmann, Caspar A.; Sorg, Martin; Jongejans, Eelke; Siepel, Henk; Hofland, Nick; Schwan, Heinz; Stenmans, Werner; Müller, Andreas; Sumser, Hubert; Hörren, Thomas; Goulson, Dave; de Kroon, Hans (18 October 2017), "More than 75 percent decline over 27 years in total flying insect biomass in protected areas", PLoS ONE, 12 (10): e0185809, Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1285809H, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185809, PMC 5646769, PMID 29045418.

- Vogel, Gretchen (10 May 2017), "Where have all the insects gone?", Science, doi:10.1126/science.aal1160.

- Sánchez-Bayo, Francisco; Wyckhuys, Kris A.G. (31 January 2019), "Worldwide decline of the entomofauna: A review of its drivers", Biological Conservation, 232: 8–27, doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.01.020.

- Bélanger, J.; Pilling, D., eds. (2019), The State of the World's Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture (PDF), Rome: Commission on Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, p. 133.

- "Aktionsprogramm Insektenschutz" (in German). Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und nukleare Sicherheit. 10 October 2018.

- Leather, Simon; et al. (28 March 2019). "Insect decline will cause serious ecological harm". The Guardian.

- Labandeira, Conrad (1 January 2005), "The fossil record of insect extinction: new approaches and future directions", American Entomologist, 51: 14–29, doi:10.1093/ae/51.1.14.

- Collen, Ben; Böhm, Monika; Kemp, Rachael; Baillie, Jonathan E. M. (2012), Spineless – Status and trends of the world's invertebrates (PDF), Zoological Society of London, ISBN 978-0-900881-70-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Borrell, Brendan (4 September 2012), "One Fifth of Invertebrate Species at Risk of Extinction", Scientific American

- Schwägerl, Christian (7 July 2016). "What's Causing the Sharp Decline in Insects, and Why It Matters". Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies.

- The Editorial Board (29 October 2017), "Insect Armageddon", The New York Times, archived from the original on 30 October 2017, retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Leather, Simon (20 December 2017), "'Ecological Armageddon' – more evidence for the drastic decline in insect numbers" (PDF), Annals of Applied Biology, 172: 1–3, doi:10.1111/aab.12410.

- Jarvis, Brooke (27 November 2018), "The Insect Apocalypse Is Here", The New York Times Magazine.

- Carrington, Damian (18 October 2017), "Warning of 'ecological Armageddon' after dramatic plunge in insect numbers", The Guardian.

- Thomas, Chris D.; Jones, T. Hefin; Hartley, Sue E. (18 March 2019). "'Insectageddon': A call for more robust data and rigorous analyses". Invited letter to the editor. Global Change Biology. 25 (6): 1891–1892. Bibcode:2019GCBio..25.1891T. doi:10.1111/gcb.14608. PMID 30821400.

- Reckhaus, Hans-Dietrich (2017), Why Every Fly Counts: A Documentation about the Value and Endangerment of Insects, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–5, ISBN 978-3-319-58765-3.

- Global Insect Biodiversity:Frequently Asked Questions (PDF), Entomological Society of America, March 2019.

- Tscharntke, Teja; Klein, Alexandra M.; Kruess, Andreas; Steffan-Dewenter, Ingolf; Thies, Carsten (August 2005). "Landscape perspectives on agricultural intensification and biodiversity and ecosystem service management". Ecology Letters. 8 (8): 857–874. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00782.x. S2CID 54532666.

- Sauvion; Calatayud, Nicolas; Thiéry; Denis (2017). Insect-plant interactions in a crop protection perspective. London: Elsevier/AP. pp. 313–320. ISBN 978-0-12-803324-1.

- Braak, Nora; Neve, Rebecca; Jones, Andrew K.; Gibbs, Melanie; Breuker, Casper J. (November 2018), "The effects of insecticides on butterflies – A review", Environmental Pollution, 242 (A): 507–518, doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2018.06.100, PMID 30005263.

- Wagner, David L.; Van Driesche, Roy G. (January 2010). "Threats Posed to Rare or Endangered Insects by Invasions of Nonnative Species". Annual Review of Entomology. 55 (1): 547–568. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085516. PMID 19743915.

- Owens, Avalon C. S.; Lewis, Sara M. (November 2018), "The impact of artificial light at night on nocturnal insects: A review and synthesis", Ecology and Evolution, 8 (22): 11337–11358, doi:10.1002/ece3.4557, PMC 6262936, PMID 30519447.

- Light pollution is key 'bringer of insect apocalypse' The Guardian, 2019

- Nutrient dilution and climate cycles underlie declines in a dominant insect herbivore PNAS, 2020

- Main, Douglas (14 February 2019). "Why insect populations are plummeting—and why it matters". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 15 February 2019.

- van Klink, Roel (24 April 2020), "Meta-analysis reveals declines in terrestrial but increases in freshwater insect abundances", Science, doi:10.1126/science.aax9931 (inactive 2020-06-06)

- Wagner, David L (January 2010). "Insect Declines in the Anthropocene". Annual Review of Entomology. 55 (1): 547–568. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-011019-025151. PMID 31610138.

- Dirzo, Rodolfo; Young, Hillary; Galetti, Mauro; Ceballos, Gerardo; Isaac, Nick; Collen, Ben (25 July 2014), "Defaunation in the Anthropocene" (PDF), Science, 345 (6195): 401–406, Bibcode:2014Sci...345..401D, doi:10.1126/science.1251817, PMID 25061202.

- Baranov, Viktor (February 2020). "Complex and nonlinear climate‐driven changes in freshwater insect communities over 42 years". Conservation Biology. doi:10.1111/cobi.13477. PMID 32022305.

- "About The Insect Survey". Rothamsted Research.

- Sorg, M.; Schwan, H.; Stenmans, W.; Müller, A. (2013). "Ermittlung der Biomassen flugaktiver Insekten im Naturschutzgebiet Orbroicher Bruch mit Malaise Fallen in den Jahren 1989 und 2013" (PDF). Mitteilungen aus dem Entomologischen Verein Krefeld. 1: 1–5.

- "Zum Insektenbestand in Deutschland: Reaktionen von Fachpublikum und Verbänden auf eine neue Studie" (PDF). Wissenschaftliche Dienste, Deutscher Bundestag (German parliament). 13 November 2017. p. 5.

- "Flying insects are disappearing from German skies". Nature. 550 (7677): 433. 18 October 2017. Bibcode:2017Natur.550Q.433.. doi:10.1038/d41586-017-04774-7. PMID 32080395.

- Guarino, Ben (18 October 2017). "'This is very alarming!': Flying insects vanish from nature preserves". The Washington Post.

- Stager, Curt (26 May 2018), "The Silence of the Bugs", The New York Times, archived from the original on 27 May 2018, retrieved 9 April 2019.

- "Cry of cicadas: The insect apocalypse is not here but there are reasons for concern", The Economist, 430 (9135): 71, 23 March 2019, archived from the original on 23 March 2019, retrieved 26 March 2019.

- McGrane, Sally (4 December 2017), "The German Amateurs Who Discovered 'Insect Armageddon'", The New York Times.

- Lister, Bradford C.; Garcia, Andres (October 2018), "Climate-driven declines in arthropod abundance restructure a rainforest food web", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115 (44): E10397–E10406, doi:10.1073/pnas.1722477115, PMC 6217376, PMID 30322922.

- Guarino, Ben (15 October 2018). "'Hyperalarming' study shows massive insect loss". The Washington Post.

- van Strien, Arco J.; van Swaay, Chris A. M.; van Strien-van Liempt, Willy T. F. H.; Poot, Martin J. M.; Wallis De Vries, Michiel F. (27 March 2019), "Over a century of data reveal more than 80% decline in butterflies in the Netherlands", Biological Conservation, 234: 116–122, doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.023.

- "Over 80% decline in butterflies since late 1800s". Statistics Netherlands (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 29 March 2019. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019.

- "Veel minder vlinders". De Telegraaf. 29 March 2019.

- Barkham, Patrick (1 April 2019), "Butterfly numbers fall by 84% in Netherlands over 130 years – study", The Guardian.

- Swiss scientists call for action on disappearing insects, Swissinfo, 13 April 2019

- Altermatt, Florian; Baur, Bruno; Gonseth, Yves; Knop, Eva; Pasinelli, Gilberto; Pauli, Daniela; Pellisier, Loïc (2 April 2019), Disparition des insectes en Suisse et conséquences éventuelles pour la société et l'économie, Swiss Academy of Natural Sciences

- "Fig. 1. Geographic location of the 73 reports studied on the world map", Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys 2019.

- LePage, Michael (11 February 2019). "Huge global extinction risk for insects could be worse than we thought". New Scientist.

- Wagner, David L. (4 March 2019), "Global insect decline: Comments on Sánchez-Bayo and Wyckhuys (2019)", Biological Conservation, 233: 332–333, doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.03.005.

- Simmons, Benno I.; Balmford, Andrew; Bladon, Andrew J.; et al. (5 April 2019). "Worldwide insect declines: An important message, but interpret with caution". Ecology and Evolution. 9 (7): 3678–3680. doi:10.1002/ece3.5153. PMC 6467851. PMID 31015957.

- Carrington, Damian (10 February 2019), "Plummeting insect numbers 'threaten collapse of nature'", The Observer.

- Saunders, Manu (16 February 2019), "Insectageddon is a great story. But what are the facts?", ecologyisnotadirtyword.com.

- Farah, Troy (6 March 2019), "Are Insects Going Extinct? The Debate Obscures the Real Dangers They Face", Discover.

- Komonen, Atte; Halme, Panu; Kotiaho, Janne S. (19 March 2019). "Alarmist by bad design: Strongly popularized unsubstantiated claims undermine credibility of conservation science". Rethinking Ecology. 4: 17–19. doi:10.3897/rethinkingecology.4.34440.

- Díaz, Sandra; Settele, Josef; Brondízio, Eduardo (6 May 2019), da Cunha, Manuela Carneiro; Mace, Georgina; Mooney, Harold (eds.), Summary for policymakers of the global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (PDF), Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services

- Crossley, Michael (10 August 2020). "No net insect abundance and diversity declines across US Long Term Ecological Research sites". Nature Ecology and Evolution. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1269-4. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- McKie, Robin (17 June 2018), "Where have all our insects gone?", The Observer.

- McCarthy, Michael (21 October 2017), "A giant insect ecosystem is collapsing due to humans. It's a catastrophe", The Guardian.

- Hance, Jeremy (3 June 2019), "Butterfly numbers fall by 84% in Netherlands over 130 years – study", Mongabay.

- Knapton, Sarah (17 June 2018), "'The windscreen phenomenon' – why your car is no longer covered in dead insects", The Telegraph.

- Linn, Virginia (4 June 2006). "Splatter-gories: Those bugs on your windshield can tell volumes about our environment". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016.

- Kirby, Alex (1 September 2004). "Scarce insects duck UK splat test". BBC News.

- Duffy, Carol Ann (27 April 2019). "Into thin air: Carol Ann Duffy presents poems about our vanishing insect world". The Guardian.

- Dangles, Olivier; Casas, Jérôme (February 2019), "Ecosystem services provided by insects for achieving sustainable development goals", Ecosystem Services: Science, Policy and Practice, 35: 109–115, doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2018.12.002.

- "Sustainable Development Goals". Division for Sustainable Development Goals, United Nations.

- "Record Low Number of Overwintering Monarch Butterflies in California—They Need Your Help!". Xerces Society.

- Katherine Roth (15 January 2019), Apps let everyone help track health of insect populations, Associated Press.

- Yong, Ed (19 February 2019), "Is the Insect Apocalypse Really Upon Us?", The Atlantic.

- Alexandra Sifferlin (14 February 2018), "Fewer Scientists Are Studying Insects. Here's Why That's So Dangerous", TIME

- McLain, Craig (19 January 2011), "The Mass Extinction of Scientists Who Study Species", Wired

- Jackson, James (26 March 2019), Entomology is going extinct, Deutsche Welle

- Leather, Simon (January 2007), "British Entomology in terminal decline?", Antenna, 31 (4): 192.

- Gangwani, Kiran; Landin, Jennifer (12 December 2018), "The Decline of Insect Representation in Biology Textbooks Over Time", American Entomologist, 64 (4): 252–257, doi:10.1093/ae/tmy064.

- Blakemore, Erin (12 December 2018), "Insects are disappearing from science textbooks—and that should bug you", Popular Science.

- Hart, Adam, "Inside the killing jar", The Biologist, 65 (2): 26–29.

- Fischer, Bob; Larson, Brendan (25 February 2019), "Collecting insects to conserve them: a call for ethical caution", Insect Conservation and Diversity, 12 (3): 173–182, doi:10.1111/icad.12344

Further reading

- "Insect Population". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 656. House of Commons (UK). 20 March 2019. col. 365WH–374WH.

- "Oral evidence: Planetary Health, HC 1803". Environmental Audit Select Committee, House of Commons (UK), 12 February 2019.

- "Zum Insektenbestand in Deutschland: Reaktionen von Fachpublikum und Verbänden auf eine neue Studie". Wissenschaftliche Dienste, Deutscher Bundestag (German parliament), 13 November 2017.