World-systems theory

World-systems theory (also known as world-systems analysis or the world-systems perspective)[1] is a multidisciplinary, macro-scale approach to world history and social change which emphasizes the world-system (and not nation states) as the primary (but not exclusive) unit of social analysis.[1][2]

"World-system" refers to the inter-regional and transnational division of labor, which divides the world into core countries, semi-periphery countries, and the periphery countries.[2] Core countries focus on higher skill, capital-intensive production, and the rest of the world focuses on low-skill, labor-intensive production and extraction of raw materials.[3] This constantly reinforces the dominance of the core countries.[3] Nonetheless, the system has dynamic characteristics, in part as a result of revolutions in transport technology, and individual states can gain or lose their core (semi-periphery, periphery) status over time.[3] This structure is unified by the division of labour. It is a world-economy rooted in a capitalist economy.[4] For a time, certain countries become the world hegemon; during the last few centuries, as the world-system has extended geographically and intensified economically, this status has passed from the Netherlands, to the United Kingdom and (most recently) to the United States.[3]

World-systems theory has been examined by many political theorists and sociologists to explain the reasons for the rise and fall of states, income inequality, social unrest, and imperialism.

Background

Immanuel Wallerstein has developed the best-known version of world-systems analysis, beginning in the 1970s.[5][6] Wallerstein traces the rise of the capitalist world-economy from the "long" 16th century (c. 1450–1640). The rise of capitalism, in his view, was an accidental outcome of the protracted crisis of feudalism (c. 1290–1450).[7] Europe (the West) used its advantages and gained control over most of the world economy and presided over the development and spread of industrialization and capitalist economy, indirectly resulting in unequal development.[2][3][6]

Though other commentators refer to Wallerstein's project as world-systems "theory", he consistently rejects that term.[8] For Wallerstein, world-systems analysis is a mode of analysis that aims to transcend the structures of knowledge inherited from the 19th century, especially the definition of capitalism, the divisions within the social sciences, and those between the social sciences and history.[9] For Wallerstein, then, world-systems analysis is a "knowledge movement"[10] that seeks to discern the "totality of what has been paraded under the labels of the... human sciences and indeed well beyond".[11] "We must invent a new language," Wallerstein insists, to transcend the illusions of the "three supposedly distinctive arenas" of society, economy and politics.[12] The trinitarian structure of knowledge is grounded in another, even grander, modernist architecture, the distinction of biophysical worlds (including those within bodies) from social ones: "One question, therefore, is whether we will be able to justify something called social science in the twenty-first century as a separate sphere of knowledge."[13][14] Many other scholars have contributed significant work in this "knowledge movement".[2]

Origins

Influences and major thinkers

World-systems theory traces emerged in the 1970s.[1] Its roots can be found in sociology, but it has developed into a highly interdisciplinary field.[2] World-systems theory was aiming to replace modernization theory, which Wallerstein criticised for three reasons:[2]

- its focus on the nation state as the only unit of analysis

- its assumption that there is only a single path of evolutionary development for all countries

- its disregard of transnational structures that constrain local and national development.

There are three major predecessors of world-systems theory: the Annales school, the Marxist tradition, and the dependence theory.[2][15] The Annales School tradition (represented most notably by Fernand Braudel) influenced Wallerstein to focusing on long-term processes and geo-ecological regions as unit of analysis. Marxism added a stress on social conflict, a focus on the capital accumulation process and competitive class struggles, a focus on a relevant totality, the transitory nature of social forms and a dialectical sense of motion through conflict and contradiction.

World-systems theory was also significantly influenced by dependency theory, a neo-Marxist explanation of development processes.

Other influences on the world-systems theory come from scholars such as Karl Polanyi, Nikolai Kondratiev[16] and Joseph Schumpeter (particularly their research on business cycles and the concepts of three basic modes of economic organization: reciprocal, redistributive, and market modes, which Wallerstein reframed into a discussion of mini systems, world empires, and world economies).

Wallerstein sees the development of the capitalist world economy as detrimental to a large proportion of the world's population.[17] Wallerstein views the period since the 1970s as an "age of transition" that will give way to a future world system (or world systems) whose configuration cannot be determined in advance.[18]

World-systems thinkers include Oliver Cox, Samir Amin, Giovanni Arrighi, Andre Gunder Frank, and Immanuel Wallerstein, with major contributions by Christopher Chase-Dunn, Beverly Silver, Volker Bornschier, Janet Abu Lughod, Thomas D. Hall, Kunibert Raffer, Theotonio dos Santos, Dale Tomich, Jason W. Moore and others.[2] In sociology, a primary alternative perspective is World Polity Theory, as formulated by John W. Meyer.

Dependency theory

World-systems analysis builds upon but also differs fundamentally from dependency theory. While accepting world inequality, the world market and imperialism as fundamental features of historical capitalism, Wallerstein broke with orthodox dependency theory's central proposition. For Wallerstein, core countries do not exploit poor countries for two basic reasons.

Firstly, core capitalists exploit workers in all zones of the capitalist world economy (not just the periphery) and therefore, the crucial redistribution between core and periphery is surplus value, not "wealth" or "resources" abstractly conceived. Secondly, core states do not exploit poor states, as dependency theory proposes, because capitalism is organised around an inter-regional and transnational division of labor rather than an international division of labour.

During the Industrial Revolution, for example, English capitalists exploited slaves (unfree workers) in the cotton zones of the American South, a peripheral region within a semiperipheral country, United States.[19]

From a largely Weberian perspective, Fernando Henrique Cardoso described the main tenets of dependency theory as follows:

- There is a financial and technological penetration of the periphery and semi-periphery countries by the developed capitalist core countries.

- That produces an unbalanced economic structure within the peripheral societies and between them and the central countries.

- That leads to limitations upon self-sustained growth in the periphery.

- That helps the appearance of specific patterns of class relations.

- They require modifications in the role of the state to guarantee the functioning of the economy and the political articulation of a society, which contains, within itself, foci of inarticulateness and structural imbalance.[20]

Dependency and world system theory propose that the poverty and backwardness of poor countries are caused by their peripheral position in the international division of labor. Since the capitalist world system evolved, the distinction between the central and the peripheral states has grown and diverged. In recognizing a tripartite pattern in division of labor, world-systems analysis criticized dependency theory with its bimodal system of only cores and peripheries.

Immanuel Wallerstein

The best-known version of the world-systems approach was developed by Immanuel Wallerstein.[6] Wallerstein notes that world-systems analysis calls for a unidisciplinary historical social science and contends that the modern disciplines, products of the 19th century, are deeply flawed because they are not separate logics, as is manifest for example in the de facto overlap of analysis among scholars of the disciplines.[1] Wallerstein offers several definitions of a world-system, defining it in 1974 briefly:

a system is defined as a unit with a single division of labor and multiple cultural systems.[21]

He also offered a longer definition:

...a social system, one that has boundaries, structures, member groups, rules of legitimation, and coherence. Its life is made up of the conflicting forces which hold it together by tension and tear it apart as each group seeks eternally to remold it to its advantage. It has the characteristics of an organism, in that it has a life-span over which its characteristics change in some respects and remain stable in others. One can define its structures as being at different times strong or weak in terms of the internal logic of its functioning.

— [22]

In 1987, Wallerstein again defined it:

... not the system of the world, but a system that is a world and which can be, most often has been, located in an area less than the entire globe. World-systems analysis argues that the units of social reality within which we operate, whose rules constrain us, are for the most part such world-systems (other than the now extinct, small minisystems that once existed on the earth). World-systems analysis argues that there have been thus far only two varieties of world-systems: world-economies and world empires. A world-empire (examples, the Roman Empire, Han China) are large bureaucratic structures with a single political center and an axial division of labor, but multiple cultures. A world-economy is a large axial division of labor with multiple political centers and multiple cultures. In English, the hyphen is essential to indicate these concepts. "World system" without a hyphen suggests that there has been only one world-system in the history of the world.

— [1]

Wallerstein characterizes the world system as a set of mechanisms, which redistributes surplus value from the periphery to the core. In his terminology, the core is the developed, industrialized part of the world, and the periphery is the "underdeveloped", typically raw materials-exporting, poor part of the world; the market being the means by which the core exploits the periphery.

Apart from them, Wallerstein defines four temporal features of the world system. Cyclical rhythms represent the short-term fluctuation of economy, and secular trends mean deeper long run tendencies, such as general economic growth or decline.[1][2] The term contradiction means a general controversy in the system, usually concerning some short term versus long term tradeoffs. For example, the problem of underconsumption, wherein the driving down of wages increases the profit for capitalists in the short term, but in the long term, the decreasing of wages may have a crucially harmful effect by reducing the demand for the product. The last temporal feature is the crisis: a crisis occurs if a constellation of circumstances brings about the end of the system.

In Wallerstein's view, there have been three kinds of historical systems across human history: "mini-systems" or what anthropologists call bands, tribes, and small chiefdoms, and two types of world-systems, one that is politically unified and the other is not (single state world empires and multi-polity world economies).[1][2] World-systems are larger, and are ethnically diverse. The modern world-system, a capitalist world-economy, is unique in being the first and only world-system, which emerged around 1450 to 1550, to have geographically expanded across the entire planet, by about 1900. It is defined, as a world-economy, in having many political units tied together as an interstate system and through its division of labor based on capitalist enterprises.[23]

Importance

World-Systems Theory can be useful in understanding world history and the core countries' motives for imperialization and other involvements like the US aid following natural disasters in developing Central American countries or imposing regimes on other core states.[24] With the interstate system as a system constant, the relative economic power of the three tiers points to the internal inequalities that are on the rise in states that appear to be developing.[25] Some argue that this theory, though, ignores local efforts of innovation that have nothing to do with the global economy, such as the labor patterns implemented in Caribbean sugar plantations.[26] Other modern global topics can be easily traced back to the world-systems theory.

As global talk about climate change and the future of industrial corporations, the world systems theory can help to explain the creation of the G-77 group, a coalition of 77 peripheral and semi-peripheral states wanting a seat at the global climate discussion table. The group was formed in 1964, but it now has more than 130 members who advocate for multilateral decision making. Since its creation, G-77 members have collaborated for two main causes: 1) decreasing their vulnerability based on the relative size of economic influence and 2) improve outcomes for national development.[27] World-systems theory has also been utilized to trace CO2 emissions’ damage to the ozone layer. The levels of world economic entrance and involvement can affect the damage a country does to the earth. In general, scientists can make assumptions about a country's CO2 emissions based on GDP. Higher exporting countries, countries with debt, and countries with social structure turmoil land in the upper-periphery tier. Though more research must be done in the arena, scientists can call core, semi-periphery, and periphery labels as indicators for CO2 intensity.[28]

In a health realm, studies have shown the effect of less industrialized countries’, the periphery's, acceptance of packaged foods and beverages that are loaded with sugars and preservatives. While core states benefit from dumping large amounts of processed, fatty foods into poorer states, there has been a recorded increase in obesity and related chronic conditions such as diabetes and chronic heart disease. While some aspects of the modernization theory have been found to improve the global obesity crisis, a world systems theory approach identifies holes in the progress.[29]

Knowledge economy and finance now dominate the industry in core states while manufacturing has shifted to semi-periphery and periphery ones.[30] Technology has become a defining factor in the placement of states into core or semi-periphery versus periphery.[31] Wallerstein's theory leaves room for poor countries to move into better economic development, but he also admits that there will always be a need for periphery countries as long as there are core states who derive resources from them.[32] As a final mark of modernity, Wallerstein admits that advocates are the heart of this world-system: “Exploitation and the refusal to accept exploitation as either inevitable or just constitute the continuing antinomy of the modern era”.[33]

Research questions

World-systems theory asks several key questions:

- How is the world system affected by changes in its components (e.g. nations, ethnic groups, social classes, etc.)?[2]

- How does it affect its components?[2]

- To what degree, if any, does the core need the periphery to be underdeveloped?[2]

- What causes world systems to change?[2]

- What system may replace capitalism?[2]

Some questions are more specific to certain subfields; for example, Marxists would concern themselves whether world-systems theory is a useful or unhelpful development of Marxist theories.[2]

Characteristics

World-systems analysis argues that capitalism, as a historical system, has always integrated a variety of labor forms within a functioning division of labor (world economy). Countries do not have economies but are part of the world economy. Far from being separate societies or worlds, the world economy manifests a tripartite division of labor, with core, semiperipheral and peripheral zones. In the core zones, businesses, with the support of states they operate within, monopolise the most profitable activities of the division of labor.

There are many ways to attribute a specific country to the core, semi-periphery, or periphery. Using an empirically based sharp formal definition of "domination" in a two-country relationship, Piana in 2004 defined the "core" as made up of "free countries" dominating others without being dominated, the "semi-periphery" as the countries that are dominated (usually, but not necessarily, by core countries) but at the same time dominating others (usually in the periphery) and "periphery" as the countries dominated. Based on 1998 data, the full list of countries in the three regions, together with a discussion of methodology, can be found.

The late 18th and early 19th centuries marked a great turning point in the development of capitalism in that capitalists achieved state society power in the key states, which furthered the industrial revolution marking the rise of capitalism. World-systems analysis contends that capitalism as a historical system formed earlier and that countries do not "develop" in stages, but the system does, and events have a different meaning as a phase in the development of historical capitalism, the emergence of the three ideologies of the national developmental mythology (the idea that countries can develop through stages if they pursue the right set of policies): conservatism, liberalism, and radicalism.

Proponents of world-systems analysis see the world stratification system the same way Karl Marx viewed class (ownership versus nonownership of the means of production) and Max Weber viewed class (which, in addition to ownership, stressed occupational skill level in the production process). The core states primarily own and control the major means of production in the world and perform the higher-level production tasks. The periphery nations own very little of the world's means of production (even when they are located in periphery states) and provide less-skilled labour. Like a class system with a states, class positions in the world economy result in an unequal distribution of rewards or resources. The core states receive the greatest share of surplus production, and periphery states receive the smallest share. Furthermore, core states are usually able to purchase raw materials and other goods from non-core states at low prices and demand higher prices for their exports to non-core states. Chirot (1986) lists the five most important benefits coming to core states from their domination of periphery s:

- Access to a large quantity of raw material

- Cheap labour

- Enormous profits from direct capital investments

- A market for exports

- Skilled professional labor through migration of these people from the non-core to the core.[34]

According to Wallerstein, the unique qualities of the modern world system include its capitalistic nature, its truly global nature, and the fact that it is a world economy that has not become politically unified into a world empire.[2]

Core states

- Are the most economically diversified, wealthy, and powerful (economically and militarily)[2][6]

- Have strong central governments, controlling extensive bureaucracies and powerful militaries[2][6]

- Have stronger and more complex state institutions that help manage economic affairs internally and externally

- Have a sufficient tax base so state institutions can provide infrastructure for a strong economy

- Highly industrialised and produce manufactured goods rather than raw materials for export[2]

- Increasingly tend to specialise in information, finance and service industries

- More often in the forefront of new technologies and new industries. Examples today include high-technology electronic and biotechnology industries. Another example would be assembly-line auto production in the early 20th century.

- Has strong bourgeois and working classes[2]

- Have significant means of influence over non-core states[2]

- Relatively independent of outside control

Throughout the history of the modern world system, there has been a group of core states competing with one another for access to the world's resources, economic dominance and hegemony over periphery states. Occasionally, there has been one core state with clear dominance over others.[3] According to Immanuel Wallerstein, a core state is dominant over all the others when it has a lead in three forms of economic dominance over a period of time:

- Productivity dominance allows a country to produce products of greater quality at a cheaper price, compared to other countries.

- Productivity dominance may lead to trade dominance. Now, there is a favorable balance of trade for the dominant state since more countries are buying the products of the dominant country than buying from them.

- Trade dominance may lead to financial dominance. Now, more money is coming into the country than going out. Bankers of the dominant state tend to receive more control of the world's financial resources.[35]

Military dominance is also likely after a state reaches these three rankings. However, it has been posited that throughout the modern world system, no state has been able to use its military to gain economic dominance. Each of the past dominant states became dominant with fairly small levels of military spending and began to lose economic dominance with military expansion later on.[36] Historically, cores were found in Northwestern Europe (England, France, Netherlands) but were later in other parts of the world (such as the United States, Canada, and Australia).[3][6]

Peripheral states

- Are the least economically diversified

- Have relatively weak governments[2][6]

- Have relatively weak institutions, with tax bases too small to support infrastructural development

- Tend to depend on one type of economic activity, often by extracting and exporting raw materials to core states[2][6]

- Tend to be the least industrialized[6]

- Are often targets for investments from multinational (or transnational) corporations from core states that come into the country to exploit cheap unskilled labor in order to export back to core states

- Have a small bourgeois and a large peasant classes[2]

- Tend to have populations with high percentages of poor and uneducated people

- Tend to have very high social inequality because of small upper classes that own most of the land and have profitable ties to multinational corporations

- Tend to be extensively influenced by core states and their multinational corporations and often forced to follow economic policies that help core states and harm the long-term economic prospects of peripheral states.[2]

Historically, peripheries were found outside Europe, such as in Latin America and today in sub-Saharan Africa.[6]

Semi-peripheral states

Semi-peripheral states are those that are midway between the core and periphery.[6] Thus, they have to keep themselves from falling into the category of peripheral states and at the same time, they strive to join the category of core states. Therefore, they tend to apply protectionist policies most aggressively among the three categories of states.[23] They tend to be countries moving towards industrialization and more diversified economies. These regions often have relatively developed and diversified economies but are not dominant in international trade.[6] They tend to export more to peripheral states and import more from core states in trade. According to some scholars, such as Chirot, they are not as subject to outside manipulation as peripheral societies; but according to others (Barfield), they have "periperial-like" relations to the core.[2][37] While in the sphere of influence of some cores, semiperipheries also tend to exert their own control over some peripheries.[6] Further, semi-peripheries act as buffers between cores and peripheries[6] and thus "...partially deflect the political pressures which groups primarily located in peripheral areas might otherwise direct against core-states" and stabilise the world system.[2][3]

Semi-peripheries can come into existence from developing peripheries and declining cores.[6] Historically, two examples of semiperipheral states would be Spain and Portugal, which fell from their early core positions but still managed to retain influence in Latin America.[6] Those countries imported silver and gold from their American colonies but then had to use it to pay for manufactured goods from core countries such as England and France.[6] In the 20th century, states like the "settler colonies" of Australia, Canada and New Zealand had a semiperipheral status. In the 21st century, states like Brazil, Russia, India, Israel, China, South Korea and South Africa (BRICS) are usually considered semiperipheral.[38]

External areas

External areas are those that maintain socially necessary divisions of labor independent of the capitalist world economy.[6]

Interpretation of world history

Before the 16th century, Europe was dominated by feudal economies.[6] European economies grew from mid-12th to 14th century but from 14th to mid 15th century, they suffered from a major crisis.[3][6] Wallerstein explains this crisis as caused by the following:

- stagnation or even decline of agricultural production, increasing the burden of peasants,

- decreased agricultural productivity caused by changing climatological conditions (Little Ice Age),

- an increase in epidemics (Black Death),

- optimum level of the feudal economy having been reached in its economic cycle; the economy moved beyond it and entered a depression period.[6]

As a response to the failure of the feudal system, European society embraced the capitalist system.[6] Europeans were motivated to develop technology to explore and trade around the world, using their superior military to take control of the trade routes.[3] Europeans exploited their initial small advantages, which led to an accelerating process of accumulation of wealth and power in Europe.[3]

Wallerstein notes that never before had an economic system encompassed that much of the world, with trade links crossing so many political boundaries.[6] In the past, geographically large economic systems existed but were mostly limited to spheres of domination of large empires (such as the Roman Empire); development of capitalism enabled the world economy to extend beyond individual states.[6] International division of labor was crucial in deciding what relationships exists between different regions, their labor conditions and political systems.[6] For classification and comparison purposes, Wallerstein introduced the categories of core, semi-periphery, periphery, and external countries.[6] Cores monopolized the capital-intensive production, and the rest of the world could provide only workforce and raw resources.[3] The resulting inequality reinforced existing unequal development.[3]

According to Wallerstein there have only been three periods in which a core state dominated in the modern world-system, with each lasting less than one hundred years. In the initial centuries of the rise of European dominance, Northwestern Europe constituted the core, Mediterranean Europe the semiperiphery, and Eastern Europe and the Western hemisphere (and parts of Asia) the periphery.[3][6] Around 1450, Spain and Portugal took the early lead when conditions became right for a capitalist world-economy. They led the way in establishing overseas colonies. However, Portugal and Spain lost their lead, primarily by becoming overextended with empire-building. It became too expensive to dominate and protect so many colonial territories around the world.[36][37][39]

The first state to gain clear dominance was the Netherlands in the 17th century, after its revolution led to a new financial system that many historians consider revolutionary.[36] An impressive shipbuilding industry also contributed to their economic dominance through more exports to other countries.[34] Eventually, other countries began to copy the financial methods and efficient production created by the Dutch. After the Dutch gained their dominant status, the standard of living rose, pushing up production costs.[35]

Dutch bankers began to go outside of the country seeking profitable investments, and the flow of capital moved, especially to England.[36] By the end of the 17th century, conflict among core states increased as a result of the economic decline of the Dutch. Dutch financial investment helped England gain productivity and trade dominance, and Dutch military support helped England to defeat France, the other country competing for dominance at the time.

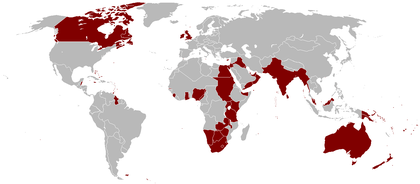

In the 19th century, Britain replaced the Netherlands as the hegemon.[3] As a result of the new British dominance, the world system became relatively stable again during the 19th century. The British began to expand globally, with many colonies in the New World, Africa, and Asia. The colonial system began to place a strain on the British military and, along with other factors, led to an economic decline. Again there was a great deal of core conflict after the British lost their clear dominance. This time it was Germany, and later Italy and Japan that provided the new threat.

Industrialization was another ongoing process during British dominance, resulting in the diminishing importance of the agricultural sector.[6] In the 18th century, Britain was Europe's leading industrial and agricultural producer; by 1900, only 10% of England's population was working in the agricultural sector.[6]

By 1900, the modern world system appeared very different from that of a century earlier in that most of the periphery societies had already been colonised by one of the older core states.[34] In 1800, the old European core claimed 35% of the world's territory, but by 1914, it claimed 85% of the world's territory, with the Scramble for Africa closing out the imperial era.[36] If a core state wanted periphery areas to exploit as had done the Dutch and British, these periphery areas had to be taken from another core state, which the US did by way of the Spanish–American War, and Germany, and then Japan and Italy, attempted to do in the leadup to World War II. The modern world system was thus geographically global, and even the most remote regions of the world had all been integrated into the global economy.[2][3]

As countries vied for core status, so did the United States. The American Civil War led to more power for the Northern industrial elites, who were now better able to pressure the government for policies helping industrial expansion. Like the Dutch bankers, British bankers were putting more investment toward the United States. The US had a small military budget compared to other industrial state at the time.[36]

The US began to take the place of the British as a new dominant state after World War I.[3] With Japan and Europe in ruins after World War II, the US was able to dominate the modern world system more than any other country in history, while the USSR and to a lesser extent China were viewed as primary threats.[3] At its height, US economic reach accounted for over half of the world's industrial production, owned two thirds of the gold reserves in the world and supplied one third of the world's exports.[36]

However, since the end of the Cold War, the future of US hegemony has been questioned by some scholars, as its hegemonic position has been in decline for a few decades.[3] By the end of the 20th century, the core of the wealthy industrialized countries was composed of Western Europe, the United States, Japan and a rather limited selection of other countries.[3] The semiperiphery was typically composed of independent states that had not achieved Western levels of influence, while poor former colonies of the West formed most of the periphery.[3]

Criticisms

World-systems theory has attracted criticisms from its rivals; notably for being too focused on economy and not enough on culture and for being too core-centric and state-centric.[2] William I. Robinson has criticized world-systems theory for its nation-state centrism, state-structuralist approach, and its inability to conceptualize the rise of globalization.[40] Robinson suggests that world-systems theory doesn't account for emerging transnational social forces and the relationships forged between them and global institutions serving their interests.[40] These forces operate on a global, rather than state system and cannot be understood by Wallerstein's nation-centered approach.[40]

According to Wallerstein himself, critique of the world-systems approach comes from four directions: the positivists, the orthodox Marxists, the state autonomists, and the culturalists.[1] The positivists criticise the approach as too prone to generalization, lacking quantitative data and failing to put forth a falsifiable proposition.[1] Orthodox Marxists find the world-systems approach deviating too far from orthodox Marxist principles, such as by not giving enough weight to the concept of social class.[1] The state autonomists criticize the theory for blurring the boundaries between state and businesses.[1] Further, the positivists and the state autonomists argue that state should be the central unit of analysis.[1] Finally, the culturalists argue that world-systems theory puts too much importance on the economy and not enough on the culture.[1] In Wallerstein's own words:

In short, most of the criticisms of world-systems analysis criticize it for what it explicitly proclaims as its perspective. World-systems analysis views these other modes of analysis as defective and/or limiting in scope and calls for unthinking them.[1]

One of the fundamental conceptual problems of the world-system theory is that the assumptions that define its actual conceptual units are social systems. The assumptions, which define them, need to be examined as well as how they are related to each other and how one changes into another. The essential argument of the world-system theory is that in the 16th century a capitalist world economy developed, which could be described as a world system.[41] The following is a theoretical critique concerned with the basic claims of world-system theory: "There are today no socialist systems in the world-economy any more than there are feudal systems because there is only one world system. It is a world-economy and it is by definition capitalist in form."[41]

Robert Brenner has pointed out that the prioritization of the world market means the neglect of local class structures and class struggles: "They fail to take into account either the way in which these class structures themselves emerge as the outcome of class struggles whose results are incomprehensible in terms merely of market forces."[41] Another criticism is that of reductionism made by Theda Skocpol: she believes the interstate system is far from being a simple superstructure of the capitalist world economy: "The international states system as a transnational structure of military competition was not originally created by capitalism. Throughout modern world history, it represents an analytically autonomous level [... of] world capitalism, but [is] not reducible to it."[41]

A concept that we can perceive as critique and mostly as renewal is the concept of coloniality (Anibal Quijano, 2000, Nepantla, Coloniality of power, eurocentrism and Latin America[42]). Issued from the think tank of the group "modernity/coloniality" (es:Grupo modernidad/colonialidad) in Latin America, it re-uses the concept of world working division and core/periphery system in its system of coloniality. But criticizing the "core-centric" origin of World-system and its only economical development, "coloniality" allows further conception of how power still processes in a colonial way over worldwide populations (Ramon Grosfogel, "the epistemic decolonial turn" 2007[43]):" by "colonial situations" I mean the cultural, political, sexual, spiritual, epistemic and economic oppression/exploitation of subordinate racialized/ethnic groups by dominant racialized/ethnic groups with or without the existence of colonial administration". Coloniality covers, so far, several fields such as coloniality of gender (Maria Lugones[44]), coloniality of "being" (Maldonado Torres), coloniality of knowledge (Walter Mignolo) and Coloniality of power (Anibal Quijano).

New developments

New developments in world systems research include studies on the cyclical processes. More specifically, it refers to the cycle of leading industries or products (ones that are new and have an important share of the overall world market for commodities), which is equal to dissolution of quasi-monopolies or other forms of partial monopolies achieved by core states. Such forms of partial monopolies are achievable through ownership of leading industries or products, which require technological capabilities, patents, restrictions on imports and/or exports, government subsidies, etc. Such capabilities are most often found in core states, which accumulate capital through achieving such quasi-monopolies with leading industries or products.

As capital is accumulated, employment and wage also increase, creating a sense of prosperity. This leads to increased production, and sometimes even overproduction, causing price competition to arise. To lower production costs, production processes of the leading industries or products are relocated to semi-peripheral states. When competition increases and quasi-monopolies cease to exist, their owners, often core states, move on to other new leading industries or products, and the cycle continues.[23]

Other new developments include the consequences of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the roles of gender and the culture, studies of slavery and incorporation of new regions into the world system and the precapitalist world systems.[2] Arguably, the greatest source of renewal in world-systems analysis since 2000 has been the synthesis of world-system and environmental approaches. Key figures in the "greening" of world-systems analysis include Minqi Li, Jason W. Moore, Andreas Malm, Stephen Bunker, Alf Hornborg, and Richard York.

Time period

Wallerstein traces the origin of today's world-system to the "long 16th century" (a period that began with the discovery of the Americas by Western European sailors and ended with the English Revolution of 1640).[2][3][6] And, according to Wallerstein, globalization, or the becoming of the world's system, is a process coterminous with the spread and development of capitalism over the past 500 years.

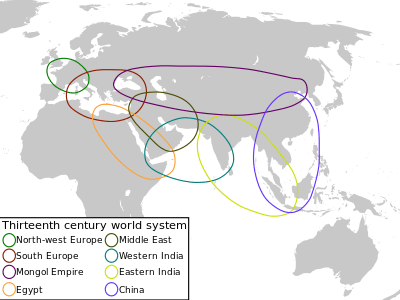

Janet Abu Lughod argues that a pre-modern world system extensive across Eurasia existed in the 13th century prior to the formation of the modern world-system identified by Wallerstein. Janet Abu Lughod contends that the Mongol Empire played an important role in stitching together the Chinese, Indian, Muslim and European regions in the 13th century, before the rise of the modern world system.[45] In debates, Wallerstein contends that Lughod's system was not a "world-system" because it did not entail integrated production networks, but it was instead a vast trading network.

Andre Gunder Frank goes further and claims that a global world system that includes Asia, Europe and Africa has existed since the 4th millennium BCE. The centre of this system was in Asia, specifically China.[46] Andrey Korotayev goes even further than Frank and dates the beginning of the world system formation to the 10th millennium BCE and connects it with the start of the Neolithic Revolution in the Middle East. According to him, the centre of this system was originally in Western Asia.[47]

Current research

Wallerstein's theories are widely recognized throughout the world. In the United States, one of the hubs of world-systems research is at the Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems and Civilizations, at Binghamton University.[2] Among the most important related periodicals are the Journal of World-Systems Research, published by the American Sociological Association's Section on the Political Economy of the World System (PEWS), and the Review, published the Braudel Center.[2]

Edythe E. Weeks asserts the proposition that it may be possible to consider, and apply critical insights, to prevent future patterns from emerging in ways to repeat outcomes harmful to humanity. (See Outer Space Development, Space Law and International Relations: A Method for Elucidating Seeds (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2012)). Her current research, as a Fulbright Specialist, further suggests that new territories such as the Antarctic Peninsula, Antarctica, the Arctic and various regions of outer space, including low Earth orbit, the geostationary orbit, Near Earth orbit are currently in the process of colonization. By applying lessons learned from our past, we can change the future towards a direction less likely to be widely criticized.

Related journals

- Annales. Histoire, Sciences sociales

- Ecology and Society

- Journal of World-Systems Research

See also

- Big History

- Dependency theory

- Structuralist economics

- Third Space Theory

- Third place

- Hybridity

- Post-colonial theory

- General systems theory

- Geography and cartography in medieval Islam

- Globalization

- International relations theory

- List of cycles

- Social cycle theory

- Sociocybernetics

- Systems philosophy

- Systems thinking

- Systemography

- War cycles

- Hierarchy theory

References

- Immanuel Wallerstein, (2004), "World-systems Analysis." In World System History, ed. George Modelski, in Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), Developed under the Auspices of the UNESCO, Eolss Publishers, Oxford, UK

- Thomas Barfield, The dictionary of anthropology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1997, ISBN 1-57718-057-7, Google Print, p.498-499

- Frank Lechner, Globalization theories: World-System Theory, 2001

- Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice (2004). World-systems analysis: An introduction. Duke University Press. pp. 23–24.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel (1974). The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic Press.

- Paul Halsall Modern History Sourcebook: Summary of Wallerstein on World System Theory, August 1997

- Wallerstein, Immanuel (1992). "The West, Capitalism, and the Modern World-System", Review 15 (4), 561-619; also Wallerstein, The Modern World-System I, chapter one; Moore, Jason W. (2003) "The Modern World-System as Environmental History? Ecology and the rise of Capitalism," Theory & Society 32(3), 307–377.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2004. The Uncertainties of Knowledge. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- So, Alvin Y. (1990). Social Change and Development: Modernization, Dependency, and World-Systems Theory. Newbury Park, London and New Delhi: Sage Publications. pp. 169–199.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2004. 2004a. "World-Systems Analysis." In World System History: Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems, edited by George Modelski. Oxford: UNESCO/EOLSS Publishers, http://www.eolss.net.

- Wallerstein, The Uncertainties of Knowledge, p. 62.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1991. "Beyond Annales," Radical History Review, no. 49, p. 14.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1995. "What Are We Bounding, and Whom, When We Bound Social Research?" Social Research 62(4):839–856.

- Moore, Jason W. 2011. 2011. "Ecology, Capital, and the Nature of Our Times: Accumulation & Crisis in the Capitalist World-Ecology," Journal of World-Systems Analysis 17(1), 108-147, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2011-02-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- Carlos A. Martínez-Vela, World Systems Theory, paper prepared for the Research Seminar in Engineering Systems, November 2003

- Kondratieff Waves in the World System Perspective. Kondratieff Waves. Dimensions and Perspectives at the Dawn of the 21st Century / Ed. by Leonid E. Grinin, Tessaleno C. Devezas, and Andrey V. Korotayev. Volgograd: Uchitel, 2012. P. 23–64.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel (1983). Historical Capitalism. London: Verso.

- Hopkins, Terence K., and Immanuel Wallerstein, coordinators (1996). The Age of Transition. London: Zed Books.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel (1989). The Modern World-System III. San Diego: Academic Press

- Cardoso, F. H. (1979). Development under Fire. Mexico D.F.: Instituto Latinoamericano de Estudios Transnacionales, DEE/D/24 i, Mayo (Mexico 20 D.F., Apartado 85 - 025). Cited after Arno Tausch, Almas Heshmati, Re-Orient? MNC Penetration and Contemporary Shifts in the Global Political Economy, September 2009, IZA Discussion Paper No. 4393

- Wallerstein, Immanuel (Sep 1974). "Wallerstein. 1974. "The Rise and Future Demise of the World-Capitalist System: Concepts for Comparative Analysis" (PDF). Comparative Studies in Society and History. 16 (4): 390. doi:10.1017/S0010417500007520. Cited after

- Immanuel Wallerstein (1974) The Modern World-System, New York, Academic Press, pp. 347-57.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel Maurice. "The Modern World System as a Capitalist World-Economy." World-Systems Analysis: An Introduction. Durham: Duke UP, 2004. 23-30. Print.

- Gowan, Peter (26 August 2004). "Contemporary Intra-Core Relations and World Systems Theory". Journal of World-Systems Research. 10 (2): 471–500. doi:10.5195/jwsr.2004.291.

- Chase-Dunn, C. (2001). World-Systems Theorizing. Handbook of Sociological Theory. https://irows.ucr.edu/cd/theory/wst1.htm

- Balkiliç, Özgür (27 September 2018). "Historicisizing World System Theory: Labor, Sugar, and Coffee in Caribbean and in Chiapas". Gaziantep University Journal of Social Sciences. 17 (4): 1298–1310. doi:10.21547/jss.380759.

- Hochstetler, Kathryn Ann (2012). "The G-77, BASIC, and global climate governance: a new era in multilateral environmental negotiations". Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional. 55 (spe): 53–69. doi:10.1590/S0034-73292012000300004.

- Roberts, J. Timmons; Grimes, Peter E.; Manale, Jodie L. (26 August 2003). "Social Roots of Global Environmental Change: A World-Systems Analysis of Carbon Dioxide Emissions". Journal of World-Systems Research. 9 (2): 277–315. doi:10.5195/jwsr.2003.238.

- Fox, A., Feng, W., & Asal, V. (2019). What is driving global obesity trends? Globalization or “modernization”? Globalization & Health, 15(1), N.PAG.

- Cartwright, Madison. (2018). Rethinking World Systems Theory and Hegemony: Towards a Marxist-Realist Synthesis. https://www.e-ir.info/2018/10/18/rethinking-world-systems-theory-and-hegemony-towards-a-marxist-realist-synthesis/

- Martínez-Vela, Carlos A. (2001). World Systems Theory. https://web.mit.edu/esd.83/www/notebook/WorldSystem.pdf

- Thompson, K. (2015). World Systems Theory. https://revisesociology.com/2015/12/05/world-systems-theory/

- Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World-System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. New York: Academic Press, 1976, pp. 229-233. https://www.csub.edu/~gsantos/WORLDSYS.HTML

- Chirot, Daniel. 1986. Social Change in the Modern Era. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1980. The Modern World System II: Mercantilism and the Consolidation of the European World-Economy, 1600-1750. New York: Academic Press.

- Kennedy, Paul. 1987. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict From 1500 to 2000. New York: Random House.

- Chirot, Daniel. 1977. Social Change in the Twentieth Century. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Morales Ruvalcaba, Daniel Efrén (11 September 2013). "INSIDE THE BRIC: ANALYSIS OF THE SEMIPERIPHERAL NATURE OF BRAZIL, RUSSIA, INDIA AND CHINA". Austral: Brazilian Journal of Strategy & International Relations (in Spanish). 2 (4). ISSN 2238-6912.

- Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1974. The Modern World System: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the 16th Century. New York: Academic Press.

- Robinson, William I. (2011-11-01). "Globalization and the sociology of Immanuel Wallerstein: A critical appraisal". International Sociology. 26 (6): 723–745. doi:10.1177/0268580910393372. ISSN 0268-5809.

- Jan Nederveen Pieterse, A Critique of World System Theory, in International Sociology, Volume 3, Issue no. 3, 1988.

- "Quijano, 2000, Nepantla, Coloniality of power, eurocentrism and Latin America" (PDF). unc.edu.

- Ramon Grosfogel, "the epistemic decolonial turn", 2007

- "M. Lugones, coloniality of gender, 2008" (PDF). duke.edu.

- Abu-Lugod, Janet (1989), "Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250-1350"

- André Gunder Frank, Barry K. Gills, The world system: five hundred years or five thousand?, Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-15089-2, Google Print, p.3

- Korotayev A. A Compact Macromodel of World System Evolution // Journal of World-Systems Research 11 (2005): 79–93 Archived 2009-07-06 at the Wayback Machine; Korotayev A., Malkov A., Khaltourina D. (2006). Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Compact Macromodels of the World System Growth. Moscow: KomKniga. ISBN 5-484-00414-4; Korotayev A. The World System urbanization dynamics. History & Mathematics: Historical Dynamics and Development of Complex Societies. Edited by Peter Turchin, Leonid Grinin, Andrey Korotayev, and Victor C. de Munck. Moscow: KomKniga, 2006. ISBN 5-484-01002-0. P. 44-62. For a detailed mathematical analysis of the issue, see A Compact Mathematical Model of the World System Economic and Demographic Growth.

Further reading

- Amin S. (1973), 'Le developpement inegal. Essai sur les formations sociales du capitalisme peripherique' Paris: Editions de Minuit.

- Amin S. (1992), 'Empire of Chaos' New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Arrighi G. (1989), 'The Developmentalist Illusion: A Reconceptualization of the Semiperiphery' paper, presented at the Thirteenth Annual Political Economy of the World System Conference, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, April 28–30.

- Arrighi G. (1994), ‘The Long 20th Century. Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times’ London, New York: Verso.

- Arrighi G. and Silver, B. J. (1984), 'Labor Movements and Capital Migration: The United States and Western Europe in World-Historical Perspective' in 'Labor in the Capitalist World-Economy' (Bergquist Ch. (Ed.)), pp. 183–216, Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Bornschier V. (Ed.) (1994), ‘Conflicts and new departures in world society’ New Brunswick, N.J. : Transaction Publishers.

- Bornschier V. (1988), 'Westliche Gesellschaft im Wandel' Frankfurt a.M./ New York: Campus.

- Bornschier V. (1996), ‘Western society in transition’ New Brunswick, N.J. : Transaction Publishers.

- Bornschier V. and Chase-Dunn Ch. K (1985), 'Transnational Corporations and Underdevelopment' N.Y., N.Y.: Praeger.

- Bornschier V. and Heintz P., reworked and enlarged by Th. H. Ballmer-Cao and J. Scheidegger (1979), 'Compendium of Data for World Systems Analysis' Machine readable data file, Zurich: Department of Sociology, Zurich University.

- Bornschier V. and Nollert M. (1994); 'Political Conflict and Labor Disputes at the Core: An Encompassing Review for the Post-War Era' in 'Conflicts and New Departures in World Society' (Bornschier V. and Lengyel P. (Eds.)), pp. 377–403, New Brunswick (U.S.A.) and London: Transaction Publishers, World Society Studies, Volume 3.

- Bornschier V. and Suter Chr. (1992), 'Long Waves in the World System' in 'Waves, Formations and Values in the World System' (Bornschier V. and Lengyel P. (Eds.)), pp. 15–50, New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

- Bornschier V. et al. (1980), 'Multinationale Konzerne, Wirtschaftspolitik und nationale Entwicklung im Weltsystem' Frankfurt a.M.: Campus

- Böröcz, József (2005), 'Redistributing Global Inequality: A Thought Experiment', Economic and Political Weekly, February 26:886-92.

- Böröcz, József (1992) 'Dual Dependency and Property Vacuum: Social Change in the State Socialist Semiperiphery' Theory & Society, 21:74-104.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. (1975), 'The Effects of International Economic Dependence on Development and Inequality: a Cross-national Study' American Sociological Review, 40: 720–738.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. (1983), 'The Kernel of the Capitalist World Economy: Three Approaches' in 'Contending Approaches to World System Analysis' (Thompson W.R. (Ed.)), pp. 55–78, Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. (1984), 'The World-System Since 1950: What Has Really Changed?' in 'Labor in the Capitalist World-Economy' (Bergquist Ch. (Ed.)), pp. 75–104, Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. (1991), 'Global Formation: Structures of the World Economy' London, Oxford and New York: Basil Blackwell.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. (1992a), 'The National State as an Agent of Modernity' Problems of Communism, January–April: 29–37.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. (1992b), 'The Changing Role of Cities in World Systems' in 'Waves, Formations and Values in the World System' (Bornschier V. and Lengyel P. (Eds.)), pp. 51–87, New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. (Ed.), (1982), 'Socialist States in the World System' Beverly Hills and London: Sage.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. and Grimes P. (1995), ‘World-Systems Analysis’ Annual Review of Sociology, 21: 387–417.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. and Hall Th. D. (1997), ‘Rise and Demise. Comparing World-Systems’ Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

- Chase-Dunn Ch. K. and Podobnik B. (1995), ‘The Next World War: World-System Cycles and Trends’ Journal of World Systems Research 1, 6 (unpaginated electronic journal at worldwide-web site of the World System Network: ).

- Frank A. G. (1978), ‘Dependent accumulation and underdevelopment’ London: Macmillan.

- Frank A. G. (1978), ‘World accumulation, 1492-1789’ London: Macmillan.

- Frank A. G. (1980) ‘Crisis in the world economy’ New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers.

- Frank A. G. (1981), ‘Crisis in the Third World’ New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers.

- Frank A. G. (1983), 'World System in Crisis' in 'Contending Approaches to World System Analysis' (Thompson W.R. (Ed.)), pp. 27–42, Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Frank A. G. (1990), 'Revolution in Eastern Europe: lessons for democratic social movements (and socialists?),' Third World Quarterly, 12, 2, April: 36–52.

- Frank A. G. (1992), 'Economic ironies in Europe: a world economic interpretation of East-West European politics' International Social Science Journal, 131, February: 41–56.

- Frank A. G. and Frank-Fuentes M. (1990), 'Widerstand im Weltsystem' Vienna: Promedia Verlag.

- Frank A. G. and Gills B. (Eds.)(1993), 'The World System: Five Hundred or Five Thousand Years?' London and New York: Routledge, Kegan&Paul.

- Grinin, L., Korotayev, A. and Tausch A. (2016) Economic Cycles, Crises, and the Global Periphery. Springer International Publishing, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London, ISBN 978-3-319-17780-9.

- Gernot Kohler and Emilio José Chaves (Editors) "Globalization: Critical Perspectives" Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science Publishers, ISBN 1-59033-346-2. With contributions by Samir Amin, Christopher Chase-Dunn, Andre Gunder Frank, Immanuel Wallerstein

- Korotayev A., Malkov A., Khaltourina D. Introduction to Social Macrodynamics: Compact Macromodels of the World System Growth. Moscow: URSS, 2006. ISBN 5-484-00414-4 .

- Lenin, Vladimir, 'Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism'

- Moore, Jason W. (2000). "Environmental Crises and the Metabolic Rift in World-Historical Perspective," Organization & Environment 13(2), 123–158.

- Raffer K. (1993), ‘Trade, transfers, and development: problems and prospects for the twenty-first century’ Aldershot, Hants, England; Brookfield, Vt., USA: E. Elgar Pub. Co.

- Raffer K. and Singer H.W. (1996), ‘The Foreign Aid Business. Economic Assistance and Development Cooperation’ Cheltenham and Borookfield: Edward Alger.

- Sunkel O. (1966), 'The Structural Background of Development Problems in Latin America' Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 97, 1: pp. 22 ff.

- Sunkel O. (1972/3), 'Transnationale kapitalistische Integration und nationale Disintegration: der Fall Lateinamerika' in 'Imperialismus und strukturelle Gewalt. Analysen ueber abhaengige Reproduktion' (Senghaas D. (Ed.)), pp. 258–315, Frankfurt a.M.: suhrkamp. English version: ‘Transnational capitalism and national disintegration in Latin America’ Social and Economic Studies, 22, 1, March: 132–76.

- Sunkel O. (1978a), 'The Development of Development Thinking' in 'Transnational Capitalism and National Development. New Perspectives on Dependence' (Villamil J.J. (Ed.)), pp. 19–30, Hassocks, Sussex: Harvester Press.

- Sunkel O. (1978b), 'Transnationalization and its National Consequences' in 'Transnational Capitalism and National Development. New Perspectives on Dependence' (Villamil J.J. (Ed.)), pp. 67–94, Hassocks, Sussex: Harvester Press.

- Sunkel O. (1980), ‘Transnacionalizacion y dependencia‘ Madrid: Ediciones Cultura Hispanica del Instituto de Cooperacion Iberoamericana.

- Sunkel O. (1984), ‘Capitalismo transnacional y desintegracion nacional en America Latina’ Buenos Aires, Rep. Argentina : Ediciones Nueva Vision.

- Sunkel O. (1990), ‘Dimension ambiental en la planificacion del desarrollo. English The environmental dimension in development planning ‘ 1st ed. Santiago, Chile : United Nations, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

- Sunkel O. (1991), ‘El Desarrollo desde dentro: un enfoque neoestructuralista para la America Latina’ 1. ed. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Economica.

- Sunkel O. (1994), ‘Rebuilding capitalism: alternative roads after socialism and dirigisme’ Ann Arbor, Mich.: University of Michigan Press

- Tausch A. and Christian Ghymers (2006), 'From the "Washington" towards a "Vienna Consensus"? A quantitative analysis on globalization, development and global governance'. Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science.

External links

| Library resources about World-systems theory |

- Journal of World-Systems Research

- Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems and Civilizations, Binghamton University, New York

- Review, A Journal of the Fernand Braudel Center

- Institute for Research on World-Systems (IROWS), University of California, Riverside

- Andre Gunder Frank resources, Rogers State University

- Immanuel Wallerstein resources, Rogers State University

- Gotts, N.M. 2007. "Resilience, Panarchy, and World-Systems Analysis," ECOLOGY & SOCIETY 12(1)

- Toll, Matthew. 2008. "The Nation-State, Core and Periphery: A Brief sketch of Imperialism in the 20th century"