Adenosine triphosphate

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) is an organic compound and hydrotrope that provides energy to drive many processes in living cells, e.g. muscle contraction, nerve impulse propagation, condensate dissolution, and chemical synthesis. Found in all known forms of life, ATP is often referred to as the "molecular unit of currency" of intracellular energy transfer.[2] When consumed in metabolic processes, it converts either to adenosine diphosphate (ADP) or to adenosine monophosphate (AMP). Other processes regenerate ATP so that the human body recycles its own body weight equivalent in ATP each day.[3] It is also a precursor to DNA and RNA, and is used as a coenzyme.

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.258 |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C10H16N5O13P3 | |

| Molar mass | 507.18 g/mol |

| Density | 1.04 g/cm3 (disodium salt) |

| Melting point | 187 °C (369 °F; 460 K) disodium salt; decomposes |

| Acidity (pKa) | 6.5 |

| UV-vis (λmax) | 259 nm[1] |

| Absorbance | ε259 = 15.4 mM−1 cm−1 [1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

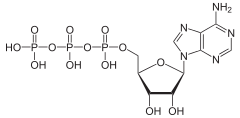

From the perspective of biochemistry, ATP is classified as a nucleoside triphosphate, which indicates that it consists of three components: a nitrogenous base (adenine), the sugar ribose, and the triphosphate.

Structure

In terms of its structure, ATP consists of an adenine attached by the 9-nitrogen atom to the 1′ carbon atom of a sugar (ribose), which in turn is attached at the 5' carbon atom of the sugar to a triphosphate group. In its many reactions related to metabolism, the adenine and sugar groups remain unchanged, but the triphosphate is converted to di- and monophosphate, giving respectively the derivatives ADP and AMP. The three phosphoryl groups are referred to as the alpha (α), beta (β), and, for the terminal phosphate, gamma (γ).

In neutral solution, ionized ATP exists mostly as ATP4−, with a small proportion of ATP3−.[4]

Binding of metal cations to ATP

Being polyanionic and featuring a potentially chelatable polyphosphate group, ATP binds metal cations with high affinity. The binding constant for Mg2+

is (9554).[5] The binding of a divalent cation, almost always magnesium, strongly affects the interaction of ATP with various proteins. Due to the strength of the ATP-Mg2+ interaction, ATP exists in the cell mostly as a complex with Mg2+

bonded to the phosphate oxygen centers.[4][6]

A second magnesium ion is critical for ATP binding in the kinase domain.[7] The presence of Mg2+ regulates kinase activity.[8]

Chemical properties

Salts of ATP can be isolated as colorless solids.[9]

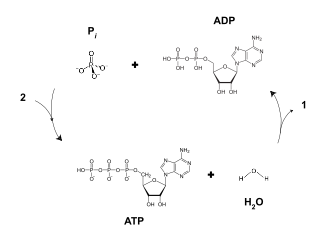

ATP is stable in aqueous solutions between pH 6.8 and 7.4, in the absence of catalysts. At more extreme pHs, it rapidly hydrolyses to ADP and phosphate. Living cells maintain the ratio of ATP to ADP at a point ten orders of magnitude from equilibrium, with ATP concentrations fivefold higher than the concentration of ADP.[10][11] In the context of biochemical reactions, the P-O-P bonds are frequently referred to as high-energy bonds.[12]

The hydrolysis of ATP into ADP and inorganic phosphate releases 30.5 kJ/mol of enthalpy, with a change in free energy of 3.4 kJ/mol.[13] The energy released by cleaving either a phosphate (Pi) or pyrophosphate (PPi) unit from ATP at standard state of 1 M are:[14]

- ATP + H

2O → ADP + Pi ΔG° = −30.5 kJ/mol (−7.3 kcal/mol) - ATP + H

2O → AMP + PPi ΔG° = −45.6 kJ/mol (−10.9 kcal/mol)

These abbreviated equations can be written more explicitly (R = adenosyl):

- [RO-P(O)2-O-P(O)2-O-PO3]4− + H

2O → [RO-P(O)2-O-PO3]3− + [PO4]3− + 2 H+ - [RO-P(O)2-O-P(O)2-O-PO3]4− + H

2O → [RO-PO3]2− + [O3P-O-PO3]4− + 2 H+

Production from AMP and ADP

Production, aerobic conditions

A typical intracellular concentration of ATP is hard to pin down, however, reports have shown there to be 1–10 μmol per gram of tissue in a variety of eukaryotes.[15] The dephosphorylation of ATP and rephosphorylation of ADP and AMP occur repeatedly in the course of aerobic metabolism.

ATP can be produced by a number of distinct cellular processes; the three main pathways in eukaryotes are (1) glycolysis, (2) the citric acid cycle/oxidative phosphorylation, and (3) beta-oxidation. The overall process of oxidizing glucose to carbon dioxide, the combination of pathways 1 and 2, known as cellular respiration, produces about 30 equivalents of ATP from each molecule of glucose.[16]

ATP production by a non-photosynthetic aerobic eukaryote occurs mainly in the mitochondria, which comprise nearly 25% of the volume of a typical cell.[17]

Glycolysis

In glycolysis, glucose and glycerol are metabolized to pyruvate. Glycolysis generates two equivalents of ATP through substrate phosphorylation catalyzed by two enzymes, PGK and pyruvate kinase. Two equivalents of NADH are also produced, which can be oxidized via the electron transport chain and result in the generation of additional ATP by ATP synthase. The pyruvate generated as an end-product of glycolysis is a substrate for the Krebs Cycle.[18]

Glycolysis is viewed as consisting of two phases with five steps each. Phase 1, "the preparatory phase", glucose is converted to 2 d-glyceraldehyde -3-phosphate (g3p). One ATP is invested in the Step 1, and another ATP is invested in Step 3. Steps 1 and 3 of glycolysis are referred to as "Priming Steps". In Phase 2, two equivalents of g3p are converted to two pyruvates . In Step 7, two ATP are produced. In addition, in Step 10, two further equivalents of ATP are produced. In Steps 7 and 10, ATP is generated from ADP. A net of two ATPs are formed in the glycolysis cycle. The glycolysis pathway is later associated with the Citric Acid Cycle which produces additional equivalents of ATP.

Regulation

In glycolysis, hexokinase is directly inhibited by its product, glucose-6-phosphate, and pyruvate kinase is inhibited by ATP itself. The main control point for the glycolytic pathway is phosphofructokinase (PFK), which is allosterically inhibited by high concentrations of ATP and activated by high concentrations of AMP. The inhibition of PFK by ATP is unusual, since ATP is also a substrate in the reaction catalyzed by PFK; the active form of the enzyme is a tetramer that exists in two conformations, only one of which binds the second substrate fructose-6-phosphate (F6P). The protein has two binding sites for ATP – the active site is accessible in either protein conformation, but ATP binding to the inhibitor site stabilizes the conformation that binds F6P poorly.[18] A number of other small molecules can compensate for the ATP-induced shift in equilibrium conformation and reactivate PFK, including cyclic AMP, ammonium ions, inorganic phosphate, and fructose-1,6- and -2,6-biphosphate.[18]

Citric acid cycle

In the mitochondrion, pyruvate is oxidized by the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex to the acetyl group, which is fully oxidized to carbon dioxide by the citric acid cycle (also known as the Krebs cycle). Every "turn" of the citric acid cycle produces two molecules of carbon dioxide, one equivalent of ATP guanosine triphosphate (GTP) through substrate-level phosphorylation catalyzed by succinyl-CoA synthetase, as succinyl- CoA is converted to Succinate, three equivalents of NADH, and one equivalent of FADH2. NADH and FADH2 are recycled (to NAD+ and FAD, respectively), generating additional ATP by oxidative phosphorylation. The oxidation of NADH results in the synthesis of 2–3 equivalents of ATP, and the oxidation of one FADH2 yields between 1–2 equivalents of ATP.[16] The majority of cellular ATP is generated by this process. Although the citric acid cycle itself does not involve molecular oxygen, it is an obligately aerobic process because O2 is used to recycle the NADH and FADH2 and provides the chemical energy driving the process.[19] In the absence of oxygen, the citric acid cycle ceases.[17]

The generation of ATP by the mitochondrion from cytosolic NADH relies on the malate-aspartate shuttle (and to a lesser extent, the glycerol-phosphate shuttle) because the inner mitochondrial membrane is impermeable to NADH and NAD+. Instead of transferring the generated NADH, a malate dehydrogenase enzyme converts oxaloacetate to malate, which is translocated to the mitochondrial matrix. Another malate dehydrogenase-catalyzed reaction occurs in the opposite direction, producing oxaloacetate and NADH from the newly transported malate and the mitochondrion's interior store of NAD+. A transaminase converts the oxaloacetate to aspartate for transport back across the membrane and into the intermembrane space.[17]

In oxidative phosphorylation, the passage of electrons from NADH and FADH2 through the electron transport chain releases the chemical energy of O2 [19] to pump protons out of the mitochondrial matrix and into the intermembrane space. This pumping generates a proton motive force that is the net effect of a pH gradient and an electric potential gradient across the inner mitochondrial membrane. Flow of protons down this potential gradient – that is, from the intermembrane space to the matrix – yields ATP by ATP synthase.[20] Three ATP are produced per turn.

Although oxygen consumption appears fundamental for the maintenance of the proton motive force, in the event of oxygen shortage (hypoxia), intracellular acidosis (mediated by enhanced glycolytic rates and ATP hydrolysis), contributes to mitochondrial membrane potential and directly drives ATP synthesis.[21]

Most of the ATP synthesized in the mitochondria will be used for cellular processes in the cytosol; thus it must be exported from its site of synthesis in the mitochondrial matrix. ATP outward movement is favored by the membrane's electrochemical potential because the cytosol has a relatively positive charge compared to the relatively negative matrix. For every ATP transported out, it costs 1 H+. Producing one ATP costs about 3 H+. Therefore, making and exporting one ATP requires 4H+. The inner membrane contains an antiporter, the ADP/ATP translocase, which is an integral membrane protein used to exchange newly synthesized ATP in the matrix for ADP in the intermembrane space.[22] This translocase is driven by the membrane potential, as it results in the movement of about 4 negative charges out across the mitochondrial membrane in exchange for 3 negative charges moved inside. However, it is also necessary to transport phosphate into the mitochondrion; the phosphate carrier moves a proton in with each phosphate, partially dissipating the proton gradient. After completing glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, the electron transport chain, and oxidative phosphorylation, approximately 30–38 ATP molecules are produced per glucose.

Regulation

The citric acid cycle is regulated mainly by the availability of key substrates, particularly the ratio of NAD+ to NADH and the concentrations of calcium, inorganic phosphate, ATP, ADP, and AMP. Citrate – the ion that gives its name to the cycle – is a feedback inhibitor of citrate synthase and also inhibits PFK, providing a direct link between the regulation of the citric acid cycle and glycolysis.[18]

Beta oxidation

In the presence of air and various cofactors and enzymes, fatty acids are converted to acetyl-CoA. The pathway is called beta-oxidation. Each cycle of beta-oxidation shortens the fatty acid chain by two carbon atoms and produces one equivalent each of acetyl-CoA, NADH, and FADH2. The acetyl-CoA is metabolized by the citric acid cycle to generate ATP, while the NADH and FADH2 are used by oxidative phosphorylation to generate ATP. Dozens of ATP equivalents are generated by the beta-oxidation of a single long acyl chain.[23]

Regulation

In oxidative phosphorylation, the key control point is the reaction catalyzed by cytochrome c oxidase, which is regulated by the availability of its substrate – the reduced form of cytochrome c. The amount of reduced cytochrome c available is directly related to the amounts of other substrates:

which directly implies this equation:

Thus, a high ratio of [NADH] to [NAD+] or a high ratio of [ADP][Pi] to [ATP] imply a high amount of reduced cytochrome c and a high level of cytochrome c oxidase activity.[18] An additional level of regulation is introduced by the transport rates of ATP and NADH between the mitochondrial matrix and the cytoplasm.[22]

Ketosis

Ketone bodies can be used as fuels, yielding 22 ATP and 2 GTP molecules per acetoacetate molecule when oxidized in the mitochondria. Ketone bodies are transported from the liver to other tissues, where acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate can be reconverted to acetyl-CoA to produce reducing equivalents (NADH and FADH2), via the citric acid cycle. Ketone bodies cannot be used as fuel by the liver, because the liver lacks the enzyme β-ketoacyl-CoA transferase, also called thiophorase. Acetoacetate in low concentrations is taken up by the liver and undergoes detoxification through the methylglyoxal pathway which ends with lactate. Acetoacetate in high concentrations is absorbed by cells other than those in the liver and enters a different pathway via 1,2-propanediol. Though the pathway follows a different series of steps requiring ATP, 1,2-propanediol can be turned into pyruvate.[24]

Production, anaerobic conditions

Fermentation is the metabolism of organic compounds in the absence of air. It involves substrate-level phosphorylation in the absence of a respiratory electron transport chain. The equation for the oxidation of glucose to lactic acid is:

- C

6H

12O

6 → 2 CH

3CH(OH)COOH + 2 ATP

Anaerobic respiration is respiration in the absence of O

2. Prokaryotes can utilize a variety of electron acceptors. These include nitrate, sulfate, and carbon dioxide.

ATP replenishment by nucleoside diphosphate kinases

ATP can also be synthesized through several so-called "replenishment" reactions catalyzed by the enzyme families of nucleoside diphosphate kinases (NDKs), which use other nucleoside triphosphates as a high-energy phosphate donor, and the ATP:guanido-phosphotransferase family.

ATP production during photosynthesis

In plants, ATP is synthesized in the thylakoid membrane of the chloroplast. The process is called photophosphorylation. The "machinery" is similar to that in mitochondria except that light energy is used to pump protons across a membrane to produce a proton-motive force. ATP synthase then ensues exactly as in oxidative phosphorylation.[25] Some of the ATP produced in the chloroplasts is consumed in the Calvin cycle, which produces triose sugars.

ATP recycling

The total quantity of ATP in the human body is about 0.2 moles. The majority of ATP is recycled from ADP by the aforementioned processes. Thus, at any given time, the total amount of ATP + ADP remains fairly constant.

The energy used by human cells in an adult requires the hydrolysis of 100 to 150 moles of ATP daily, which is around 50 to 75 kg. A human will typically use up his or her body weight of ATP over the course of the day. Each equivalent of ATP is recycled 1000–1500 times during a single day (100 / 0.2 = 500).[26]

Biochemical functions

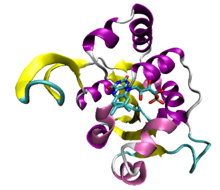

Intracellular signaling

ATP is involved in signal transduction by serving as substrate for kinases, enzymes that transfer phosphate groups. Kinases are the most common ATP-binding proteins. They share a small number of common folds.[27] Phosphorylation of a protein by a kinase can activate a cascade such as the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade.[28]

ATP is also a substrate of adenylate cyclase, most commonly in G protein-coupled receptor signal transduction pathways and is transformed to second messenger, cyclic AMP, which is involved in triggering calcium signals by the release of calcium from intracellular stores.[29] This form of signal transduction is particularly important in brain function, although it is involved in the regulation of a multitude of other cellular processes.[30]

DNA and RNA synthesis

ATP is one of four "monomers" required in the synthesis of RNA. The process is promoted by RNA polymerases.[31] A similar process occurs in the formation of DNA, except that ATP is first converted to the deoxyribonucleotide dATP. Like many condensation reactions in nature, DNA replication and DNA transcription also consumes ATP.

Amino acid activation in protein synthesis

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase enzymes consume ATP in the attachment tRNA to amino acids, forming aminoacyl-tRNA complexes. Aminoacyl transferase binds AMP-amino acid to tRNA. The coupling reaction proceeds in two steps:

- aa + ATP ⟶ aa-AMP + PPi

- aa-AMP + tRNA ⟶ aa-tRNA + AMP

The amino acid is coupled to the penultimate nucleotide at the 3′-end of the tRNA (the A in the sequence CCA) via an ester bond (roll over in illustration).

ATP binding cassette transporter

Transporting chemicals out of a cell against a gradient is often associated with ATP hydrolysis. Transport is mediated by ATP binding cassette transporters. The human genome encodes 48 ABC transporters, that are used for exporting drugs, lipids, and other compounds.[32]

Extracellular signalling and neurotransmision

Cells secrete ATP to communicate with other cells in a process called purinergic signalling. ATP serves as a neurotransmitter in many parts of the nervous system, modulates ciliary beating, affects vascular oxygen supply etc. ATP is either secreted directly across the cell membrane through channel proteins[33][34] or is pumped into vesicles[35] which then fuse with the membrane. Cells detect ATP using the purinergic receptor proteins P2X and P2Y.

Protein solubility

ATP has recently been proposed to act as a biological hydrotrope[36] and has been shown to affect proteome-wide solubility.[37]

ATP analogues

Biochemistry laboratories often use in vitro studies to explore ATP-dependent molecular processes. ATP analogs are also used in X-ray crystallography to determine a protein structure in complex with ATP, often together with other substrates.

Enzyme inhibitors of ATP-dependent enzymes such as kinases are needed to examine the binding sites and transition states involved in ATP-dependent reactions.

Most useful ATP analogs cannot be hydrolyzed as ATP would be; instead they trap the enzyme in a structure closely related to the ATP-bound state. Adenosine 5′-(γ-thiotriphosphate) is an extremely common ATP analog in which one of the gamma-phosphate oxygens is replaced by a sulfur atom; this anion is hydrolyzed at a dramatically slower rate than ATP itself and functions as an inhibitor of ATP-dependent processes. In crystallographic studies, hydrolysis transition states are modeled by the bound vanadate ion.

Caution is warranted in interpreting the results of experiments using ATP analogs, since some enzymes can hydrolyze them at appreciable rates at high concentration.[38]

Medical use

ATP is used intravenously for some heart related conditions.[39]

History

ATP was discovered in 1929 by Karl Lohmann[40] and Jendrassik[41] and, independently, by Cyrus Fiske and Yellapragada Subba Rao of Harvard Medical School,[42] both teams competing against each other to find an assay for phosphorus.

It was proposed to be the intermediary between energy-yielding and energy-requiring reactions in cells by Fritz Albert Lipmann in 1941.[43]

It was first synthesized in the laboratory by Alexander Todd in 1948.[44]

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1997 was divided, one half jointly to Paul D. Boyer and John E. Walker "for their elucidation of the enzymatic mechanism underlying the synthesis of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)" and the other half to Jens C. Skou "for the first discovery of an ion-transporting enzyme, Na+, K+ -ATPase."[45]

See also

- Adenosine diphosphate (ADP)

- Adenosine monophosphate (AMP)

- Adenosine-tetraphosphatase

- Adenosine methylene triphosphate

- ATPases

- ATP test

- ATP hydrolysis

- Citric acid cycle (also called the Krebs cycle or TCA cycle)

- Creatine

- Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)

- Nucleotide exchange factor

- Phosphagen

- Photophosphorylation

References

- "Adenosine 5'-triphosphate disodium salt Product Information" (PDF). Sigma. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-23. Retrieved 2019-03-22.

- Knowles, J. R. (1980). "Enzyme-catalyzed phosphoryl transfer reactions". Annu. Rev. Biochem. 49: 877–919. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.004305. PMID 6250450.

- Törnroth-Horsefield, S.; Neutze, R. (December 2008). "Opening and closing the metabolite gate". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105 (50): 19565–19566. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810654106. PMC 2604989. PMID 19073922.

- Storer, A.; Cornish-Bowden, A. (1976). "Concentration of MgATP2− and other ions in solution. Calculation of the true concentrations of species present in mixtures of associating ions". Biochem. J. 159 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1042/bj1590001. PMC 1164030. PMID 11772.

- Wilson, J.; Chin, A. (1991). "Chelation of divalent cations by ATP, studied by titration calorimetry". Anal. Biochem. 193 (1): 16–19. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(91)90036-S. PMID 1645933.

- Garfinkel, L.; Altschuld, R.; Garfinkel, D. (1986). "Magnesium in cardiac energy metabolism". J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 18 (10): 1003–1013. doi:10.1016/S0022-2828(86)80289-9. PMID 3537318.

- Saylor, P.; Wang, C.; Hirai, T.; Adams, J. (1998). "A second magnesium ion is critical for ATP binding in the kinase domain of the oncoprotein v-Fps". Biochemistry. 37 (36): 12624–12630. doi:10.1021/bi9812672. PMID 9730835.

- Lin, X.; Ayrapetov, M; Sun, G. (2005). "Characterization of the interactions between the active site of a protein tyrosine kinase and a divalent metal activator". BMC Biochem. 6: 25. doi:10.1186/1471-2091-6-25. PMC 1316873. PMID 16305747.

- Budavari, Susan, ed. (2001), The Merck Index: An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals (13th ed.), Merck, ISBN 0911910131

- Ferguson, S. J.; Nicholls, David; Ferguson, Stuart (2002). Bioenergetics 3 (3rd ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic. ISBN 978-0-12-518121-1.

- Berg, J. M.; Tymoczko, J. L.; Stryer, L. (2003). Biochemistry. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman. p. 376. ISBN 978-0-7167-4684-3.

- Chance, B.; Lees, H.; Postgate, J. G. (1972). "The Meaning of "Reversed Electron Flow" and "High Energy Electron" in Biochemistry". Nature. 238 (5363): 330–331. doi:10.1038/238330a0. PMID 4561837.

- Gajewski, E.; Steckler, D.; Goldberg, R. (1986). "Thermodynamics of the hydrolysis of adenosine 5′-triphosphate to adenosine 5′-diphosphate" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 261 (27): 12733–12737. PMID 3528161. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- Berg, Jeremy M.; Tymoczko, John L.; Stryer, Lubert (2007). Biochemistry (6th ed.). New York, NY: W. H. Freeman. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-7167-8724-2.

- Beis, I.; Newsholme, E. A. (October 1, 1975). "The contents of adenine nucleotides, phosphagens and some glycolytic intermediates in resting muscles from vertebrates and invertebrates". Biochem. J. 152 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1042/bj1520023. PMC 1172435. PMID 1212224.

- Rich, P. R. (2003). "The molecular machinery of Keilin's respiratory chain". Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31 (6): 1095–1105. doi:10.1042/BST0311095. PMID 14641005.

- Lodish, H.; Berk, A.; Matsudaira, P.; Kaiser, C. A.; Krieger, M.; Scott, M. P.; Zipursky, S. L.; Darnell, J. (2004). Molecular Cell Biology (5th ed.). New York, NY: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4366-8.

- Voet, D.; Voet, J. G. (2004). Biochemistry. 1 (3rd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-19350-0.

- Schmidt-Rohr, K (2020). "Oxygen Is the High-Energy Molecule Powering Complex Multicellular Life: Fundamental Corrections to Traditional Bioenergetics". ACS Omega. 5: 2221–2233. doi:10.1021/acsomega.9b03352. PMC 7016920. PMID 32064383.

- Abrahams, J.; Leslie, A.; Lutter, R.; Walker, J. (1994). "Structure at 2.8 Å resolution of F1-ATPase from bovine heart mitochondria". Nature. 370 (6491): 621–628. doi:10.1038/370621a0. PMID 8065448.

- Devaux, JBL; Hedges, CP; Hickey, AJR (January 2019). "Acidosis Maintains the Function of Brain Mitochondria in Hypoxia-Tolerant Triplefin Fish: A Strategy to Survive Acute Hypoxic Exposure?". Front Physiol. 9, 1914. doi:10.3389/fphys.2018.01941. PMC 6346031. PMID 30713504.

- Dahout-Gonzalez, C.; Nury, H.; Trézéguet, V.; Lauquin, G.; Pebay-Peyroula, E.; Brandolin, G. (2006). "Molecular, functional, and pathological aspects of the mitochondrial ADP/ATP carrier". Physiology. 21 (4): 242–249. doi:10.1152/physiol.00005.2006. PMID 16868313.

- Ronnett, G.; Kim, E.; Landree, L.; Tu, Y. (2005). "Fatty acid metabolism as a target for obesity treatment". Physiol. Behav. 85 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.04.014. PMID 15878185.

- "Integrated Risk Information System" (PDF). 2013-03-15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

- Allen, J. (2002). "Photosynthesis of ATP-electrons, proton pumps, rotors, and poise". Cell. 110 (3): 273–276. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00870-X. PMID 12176312.

- Fuhrman, Bradley P.; Zimmerman, Jerry J. (2011). Pediatric Critical Care. Elsevier. pp. 1058–1072. ISBN 978-0-323-07307-3. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- Scheeff, E.; Bourne, P. (2005). "Structural evolution of the protein kinase-like superfamily". PLoS Comput. Biol. 1 (5): e49. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010049. PMC 1261164. PMID 16244704.

- Mishra, N.; Tuteja, R.; Tuteja, N. (2006). "Signaling through MAP kinase networks in plants". Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 452 (1): 55–68. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2006.05.001. PMID 16806044.

- Kamenetsky, M.; Middelhaufe, S.; Bank, E.; Levin, L.; Buck, J.; Steegborn, C. (2006). "Molecular details of cAMP generation in mammalian cells: a tale of two systems". J. Mol. Biol. 362 (4): 623–639. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.045. PMC 3662476. PMID 16934836.

- Hanoune, J.; Defer, N. (2001). "Regulation and role of adenylyl cyclase isoforms". Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 41: 145–174. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.145. PMID 11264454.

- Joyce, C. M.; Steitz, T. A. (1995). "Polymerase structures and function: variations on a theme?". J. Bacteriol. 177 (22): 6321–6329. doi:10.1128/jb.177.22.6321-6329.1995. PMC 177480. PMID 7592405.

- Borst, P.; Elferink, R. Oude (2002). "Mammalian ABC transporters in health and disease" (PDF). Annual Review of Biochemistry. 71: 537–592. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.102301.093055. PMID 12045106. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-04-21. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- Romanov, Roman A.; Lasher, Robert S.; High, Brigit; Savidge, Logan E.; Lawson, Adam; Rogachevskaja, Olga A.; Zhao, Haitian; Rogachevsky, Vadim V.; Bystrova, Marina F.; Churbanov, Gleb D.; Adameyko, Igor; Harkany, Tibor; Yang, Ruibiao; Kidd, Grahame J.; Marambaud, Philippe; Kinnamon, John C.; Kolesnikov, Stanislav S.; Finger, Thomas E. (2018). "Chemical synapses without synaptic vesicles: Purinergic neurotransmission through a CALHM1 channel-mitochondrial signaling complex". Science Signaling. 11 (529): eaao1815. doi:10.1126/scisignal.aao1815. ISSN 1945-0877. PMC 5966022. PMID 29739879.

- Dahl, Gerhard (2015). "ATP release through pannexon channels". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 370 (1672): 20140191. doi:10.1098/rstb.2014.0191. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 4455760. PMID 26009770.

- Larsson, Max; Sawada, Keisuke; Morland, Cecilie; Hiasa, Miki; Ormel, Lasse; Moriyama, Yoshinori; Gundersen, Vidar (2012). "Functional and Anatomical Identification of a Vesicular Transporter Mediating Neuronal ATP Release". Cerebral Cortex. 22 (5): 1203–1214. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhr203. ISSN 1460-2199. PMID 21810784.

- Hyman, Anthony A.; Krishnan, Yamuna; Alberti, Simon; Wang, Jie; Saha, Shambaditya; Malinovska, Liliana; Patel, Avinash (2017-05-19). "ATP as a biological hydrotrope". Science. 356 (6339): 753–756. doi:10.1126/science.aaf6846. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 28522535.

- Savitski, Mikhail M.; Bantscheff, Marcus; Huber, Wolfgang; Dominic Helm; Günthner, Ina; Werner, Thilo; Kurzawa, Nils; Sridharan, Sindhuja (2019-03-11). "Proteome-wide solubility and thermal stability profiling reveals distinct regulatory roles for ATP". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1155. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09107-y. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6411743. PMID 30858367.

- Resetar, A. M.; Chalovich, J. M. (1995). "Adenosine 5′-(gamma-thiotriphosphate): an ATP analog that should be used with caution in muscle contraction studies". Biochemistry. 34 (49): 16039–16045. doi:10.1021/bi00049a018. PMID 8519760.

- Pelleg, Amir; Kutalek, Steven P.; Flammang, Daniel; Benditt, David (February 2012). "ATPace™: injectable adenosine 5′-triphosphate". Purinergic Signalling. 8 (Suppl 1): 57–60. doi:10.1007/s11302-011-9268-1. ISSN 1573-9538. PMC 3265710. PMID 22057692.

- Lohmann, K. (August 1929). "Über die Pyrophosphatfraktion im Muskel" [On the pyrophosphate fraction in muscle]. Naturwissenschaften (in German). 17 (31): 624–625. doi:10.1007/BF01506215.

- Vaughan, Martha; Hill, Robert L.; Simoni, Robert D. (2002). "The Determination of Phosphorus and the Discovery of Phosphocreatine and ATP: the Work of Fiske and SubbaRow". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (32): e21. Archived from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- Maruyama, K. (March 1991). "The discovery of adenosine triphosphate and the establishment of its structure". J. Hist. Biol. 24 (1): 145–154. doi:10.1007/BF00130477.

- Lipmann, F. (1941). "Metabolic generation and utilization of phosphate bond energy". Adv. Enzymol. 1: 99–162. ISSN 0196-7398.

- "History: ATP first discovered in 1929". The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1997. Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 2010-01-23. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1997". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 24 October 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Adenosine triphosphate. |

.svg.png)