Titanium dioxide

Titanium dioxide, also known as titanium(IV) oxide or titania /taɪˈteɪniə/, is the naturally occurring oxide of titanium, chemical formula TiO

2. When used as a pigment, it is called titanium white, Pigment White 6 (PW6), or CI 77891. Generally, it is sourced from ilmenite, rutile, and anatase. It has a wide range of applications, including paint, sunscreen, and food coloring. When used as a food coloring, it has E number E171. World production in 2014 exceeded 9 million tonnes.[4][5][6] It has been estimated that titanium dioxide is used in two-thirds of all pigments, and pigments based on the oxide have been valued at $13.2 billion.[7]

_oxide.jpg) | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC names

Titanium dioxide Titanium(IV) oxide | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.327 |

| E number | E171 (colours) |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| TiO 2 | |

| Molar mass | 79.866 g/mol |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density |

|

| Melting point | 1,843 °C (3,349 °F; 2,116 K) |

| Boiling point | 2,972 °C (5,382 °F; 3,245 K) |

| Insoluble | |

| Band gap | 3.05 eV (rutile)[1] |

| +5.9·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD) |

|

| Thermochemistry | |

Std molar entropy (S |

50 J·mol−1·K−1[2] |

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−945 kJ·mol−1[2] |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 0338 |

EU classification (DSD) (outdated) |

Not listed |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible) |

TWA 15 mg/m3[3] |

REL (Recommended) |

Ca[3] |

IDLH (Immediate danger) |

Ca [5000 mg/m3][3] |

| Related compounds | |

Other cations |

Zirconium dioxide Hafnium dioxide |

| Titanium(II) oxide Titanium(III) oxide Titanium(III,IV) oxide | |

Related compounds |

Titanic acid |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

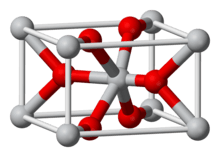

Occurrence

Titanium dioxide occurs in nature as the minerals rutile and anatase. Additionally two high-pressure forms are known minerals: a monoclinic baddeleyite-like form known as akaogiite, and the other is an orthorhombic α-PbO2-like form known as brookite, both of which can be found at the Ries crater in Bavaria.[8][9][10] It is mainly sourced from ilmenite ore. This is the most widespread form of titanium dioxide-bearing ore around the world. Rutile is the next most abundant and contains around 98% titanium dioxide in the ore. The metastable anatase and brookite phases convert irreversibly to the equilibrium rutile phase upon heating above temperatures in the range 600–800 °C (1,110–1,470 °F).[11]

Titanium dioxide has eight modifications – in addition to rutile, anatase, akaogiite, and brookite, three metastable phases can be produced synthetically (monoclinic, tetragonal, and orthorombic), and five high-pressure forms (α-PbO2-like, baddeleyite-like, cotunnite-like, orthorhombic OI, and cubic phases) also exist:

| Form | Crystal system | Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Rutile | Tetragonal | |

| Anatase | Tetragonal | |

| Brookite | Orthorhombic | |

| TiO2(B)[12] | Monoclinic | Hydrolysis of K2Ti4O9 followed by heating |

| TiO2(H), hollandite-like form[13] | Tetragonal | Oxidation of the related potassium titanate bronze, K0.25TiO2 |

| TiO2(R), ramsdellite-like form[14] | Orthorhombic | Oxidation of the related lithium titanate bronze Li0.5TiO2 |

| TiO2(II)-(α-PbO2-like form)[15] | Orthorhombic | |

| Akaogiite (baddeleyite-like form, 7 coordinated Ti)[16] | Monoclinic | |

| TiO2 -OI[17] | Orthorhombic | |

| Cubic form[18] | Cubic | P > 40 GPa, T > 1600 °C |

| TiO2 -OII, cotunnite(PbCl2)-like[19] | Orthorhombic | P > 40 GPa, T > 700 °C |

The cotunnite-type phase was claimed by L. Dubrovinsky and co-authors to be the hardest known oxide with the Vickers hardness of 38 GPa and the bulk modulus of 431 GPa (i.e. close to diamond's value of 446 GPa) at atmospheric pressure.[19] However, later studies came to different conclusions with much lower values for both the hardness (7–20 GPa, which makes it softer than common oxides like corundum Al2O3 and rutile TiO2)[20] and bulk modulus (~300 GPa).[21][22]

The oxides are commercially important ores of titanium. The metal is also be mined from other ores such as ilmenite or leucoxene, or one of the purest forms, rutile beach sand. Star sapphires and rubies get their asterism from rutile impurities present.[23]

Titanium dioxide (B) is found as a mineral in magmatic rocks and hydrothermal veins, as well as weathering rims on perovskite. TiO2 also forms lamellae in other minerals.[24]

Molten titanium dioxide has a local structure in which each Ti is coordinated to, on average, about 5 oxygen atoms.[25] This is distinct from the crystalline forms in which Ti coordinates to 6 oxygen atoms.

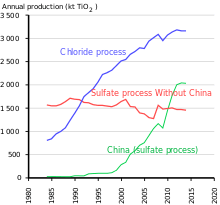

Production

The production method depends on the feedstock. The most common mineral source is ilmenite. The abundant rutile mineral sand can also be purified with the chloride process or other processes. Ilmenite is converted into pigment grade titanium dioxide via either the sulfate process or the chloride process. Both sulfate and chloride processes produce the titanium dioxide pigment in the rutile crystal form, but the Sulfate Process can be adjusted to produce the anatase form. Anatase, being softer, is used in fiber and paper applications. The Sulfate Process is run as a batch process; the Chloride Process is run as a continuous process.[26]

Plants using the Sulfate Process require ilmenite concentrate (45-60% TiO2) or pretreated feedstocks as suitable source of titanium.[27] In the sulfate process, ilmenite is treated with sulfuric acid to extract iron(II) sulfate pentahydrate. The resulting synthetic rutile is further processed according to the specifications of the end user, i.e. pigment grade or otherwise.[28] In another method for the production of synthetic rutile from ilmenite the Becher Process first oxidizes the ilmenite as a means to separate the iron component.

An alternative process, known as the chloride process converts ilmenite or other titanium sources to titanium tetrachloride via reaction with elemental chlorine, which is then purified by distillation, and reacted with oxygen to regenerate chlorine and produce the titanium dioxide. Titanium dioxide pigment can also be produced from higher titanium content feedstocks such as upgraded slag, rutile, and leucoxene via a chloride acid process.

The five largest TiO

2 pigment processors are in 2019 Chemours, Cristal Global, Venator, Kronos, and Tronox, which is the largest one.[29][30] Major paint and coating company end users for pigment grade titanium dioxide include Akzo Nobel, PPG Industries, Sherwin Williams, BASF, Kansai Paints and Valspar.[31] Global TiO

2 pigment demand for 2010 was 5.3 Mt with annual growth expected to be about 3-4%.[32]

Specialized methods

For specialty applications, TiO2 films are prepared by various specialized chemistries.[33] Sol-gel routes involve the hydrolysis of titanium alkoxides, such as titanium ethoxide:

- Ti(OEt)4 + 2 H2O → TiO2 + 4 EtOH

This technology is suited for the preparation of films. A related approach that also relies on molecular precursors involves chemical vapor deposition. In this application, the alkoxide is volatilized and then decomposed on contact with a hot surface:

- Ti(OEt)4 → TiO2 + 2 Et2O

Applications

The most important application areas are paints and varnishes as well as paper and plastics, which account for about 80% of the world's titanium dioxide consumption. Other pigment applications such as printing inks, fibers, rubber, cosmetic products, and food account for another 8%. The rest is used in other applications, for instance the production of technical pure titanium, glass and glass ceramics, electrical ceramics, metal patinas, catalysts, electric conductors, and chemical intermediates.[34]

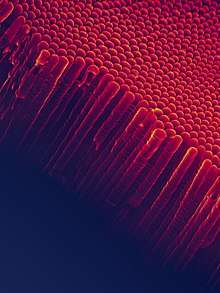

Pigment

First mass-produced in 1916,[35] titanium dioxide is the most widely used white pigment because of its brightness and very high refractive index, in which it is surpassed only by a few other materials (see list of indices of refraction). Titanium dioxide crystal size is ideally around 220 nm (measured by electron microscope) to optimize the maximum reflection of visible light. The optical properties of the finished pigment are highly sensitive to purity. As little as a few parts per million (ppm) of certain metals (Cr, V, Cu, Fe, Nb) can disturb the crystal lattice so much that the effect can be detected in quality control.[36] Approximately 4.6 million tons of pigmentary TiO2 are used annually worldwide, and this number is expected to increase as use continues to rise.[37]

TiO2 is also an effective opacifier in powder form, where it is employed as a pigment to provide whiteness and opacity to products such as paints, coatings, plastics, papers, inks, foods, medicines (i.e. pills and tablets), and most toothpastes. In paint, it is often referred to offhandedly as "brilliant white", "the perfect white", "the whitest white", or other similar terms. Opacity is improved by optimal sizing of the titanium dioxide particles.

TiO2 has been flagged as possibly carcinogenic. In 2019, it was present in two thirds of toothpastes on the French market. Bruno Le Maire, a minister in the Edouard Philippe government, promised in March 2019 to remove it from that and other alimentary uses.[38]

Thin films

When deposited as a thin film, its refractive index and colour make it an excellent reflective optical coating for dielectric mirrors; it is also used in generating decorative thin films such as found in "mystic fire topaz".

Some grades of modified titanium based pigments as used in sparkly paints, plastics, finishes and cosmetics - these are man-made pigments whose particles have two or more layers of various oxides – often titanium dioxide, iron oxide or alumina – in order to have glittering, iridescent and or pearlescent effects similar to crushed mica or guanine-based products. In addition to these effects a limited colour change is possible in certain formulations depending on how and at which angle the finished product is illuminated and the thickness of the oxide layer in the pigment particle; one or more colours appear by reflection while the other tones appear due to interference of the transparent titanium dioxide layers.[39] In some products, the layer of titanium dioxide is grown in conjunction with iron oxide by calcination of titanium salts (sulfates, chlorates) around 800 °C[40] One example of a pearlescent pigment is Iriodin, based on mica coated with titanium dioxide or iron (III) oxide.[41]

The iridescent effect in these titanium oxide particles is unlike the opaque effect obtained with usual ground titanium oxide pigment obtained by mining, in which case only a certain diameter of the particle is considered and the effect is due only to scattering.

Sunscreen and UV blocking pigments

In cosmetic and skin care products, titanium dioxide is used as a pigment, sunscreen and a thickener. As a sunscreen, ultrafine TiO2 is used, which is notable in that combined with ultrafine zinc oxide, it is considered to be an effective sunscreen that is less harmful to coral reefs than sunscreens that include chemicals such as oxybenzone and octinoxate.

Nanosized titanium dioxide is found in the majority of physical sunscreens because of its strong UV light absorbing capabilities and its resistance to discolouration under ultraviolet light. This advantage enhances its stability and ability to protect the skin from ultraviolet light. Nano-scaled (particle size of 20–40 nm)[42] titanium dioxide particles are primarily used in sunscreen lotion because they scatter visible light much less than titanium dioxide pigments, and can give UV protection.[37] Sunscreens designed for infants or people with sensitive skin are often based on titanium dioxide and/or zinc oxide, as these mineral UV blockers are believed to cause less skin irritation than other UV absorbing chemicals. Nano-TiO2 blocks both UV-A and UV-B radiation, which is used in sunscreens and other cosmetic products. It is safe to use and it is better to environment than organic UV-absorbers.[43]

TiO

2 is used extensively in plastics and other applications as a white pigment or an opacifier and for its UV resistant properties where the powder disperses light – unlike organic UV absorbers – and reduces UV damage, due mostly to the particle's high refractive index.[44]

Other uses of titanium dioxide

In ceramic glazes, titanium dioxide acts as an opacifier and seeds crystal formation.

It is used as a tattoo pigment and in styptic pencils. Titanium dioxide is produced in varying particle sizes, oil and water dispersible, and in certain grades for the cosmetic industry.

Research

Photocatalyst

Nanosized titanium dioxide, particularly in the anatase form, exhibits photocatalytic activity under ultraviolet (UV) irradiation. This photoactivity is reportedly most pronounced at the {001} planes of anatase,[45][46] although the {101} planes are thermodynamically more stable and thus more prominent in most synthesised and natural anatase,[47] as evident by the often observed tetragonal dipyramidal growth habit. Interfaces between rutile and anatase are further considered to improve photocatalytic activity by facilitating charge carrier separation and as a result, biphasic titanium dioxide is often considered to possess enhanced functionality as a photocatalyst.[48] It has been reported that titanium dioxide, when doped with nitrogen ions or doped with metal oxide like tungsten trioxide, exhibits excitation also under visible light.[49] The strong oxidative potential of the positive holes oxidizes water to create hydroxyl radicals. It can also oxidize oxygen or organic materials directly. Hence, in addition to its use as a pigment, titanium dioxide can be added to paints, cements, windows, tiles, or other products for its sterilizing, deodorizing, and anti-fouling properties, and is used as a hydrolysis catalyst. It is also used in dye-sensitized solar cells, which are a type of chemical solar cell (also known as a Graetzel cell).

The photocatalytic properties of nanosized titanium dioxide were discovered by Akira Fujishima in 1967[50] and published in 1972.[51] The process on the surface of the titanium dioxide was called the Honda-Fujishima effect (ja:本多-藤嶋効果).[50] Titanium dioxide, in thin film and nanoparticle form has potential for use in energy production: as a photocatalyst, it can break water into hydrogen and oxygen. With the hydrogen collected, it could be used as a fuel. The efficiency of this process can be greatly improved by doping the oxide with carbon.[52] Further efficiency and durability has been obtained by introducing disorder to the lattice structure of the surface layer of titanium dioxide nanocrystals, permitting infrared absorption.[53] Visible-light-active nanosized anatase and rutile has been developed for photocatalytic applications.[54][55]

In 1995 Fujishima and his group discovered the superhydrophilicity phenomenon for titanium dioxide coated glass exposed to sun light.[50] This resulted in the development of self-cleaning glass and anti-fogging coatings.

Nanosized TiO2 incorporated into outdoor building materials, such as paving stones in noxer blocks[56] or paints, can substantially reduce concentrations of airborne pollutants such as volatile organic compounds and nitrogen oxides.[57] A cement that uses titanium dioxide as a photocatalytic component, produced by Italcementi Group, was included in Time Magazine's Top 50 Inventions of 2008.[58]

Attempts have been made to photocatalytically mineralize pollutants (to convert into CO2 and H2O) in waste water.[59] TiO2 offers great potential as an industrial technology for detoxification or remediation of wastewater due to several factors:[60]

- The process uses natural oxygen and sunlight and thus occurs under ambient conditions; it is wavelength selective and is accelerated by UV light.

- The photocatalyst is inexpensive, readily available, non-toxic, chemically and mechanically stable, and has a high turnover.

- The formation of photocyclized intermediate products, unlike direct photolysis techniques, is avoided.

- Oxidation of the substrates to CO2 is complete.

- TiO2 can be supported as thin films on suitable reactor substrates, which can be readily separated from treated water.[61]

The photocatalytic destruction of organic matter is also exploited in photocatalytic antimicrobial coatings,[62] which are typically thin films applied to furniture in hospitals and other surfaces susceptible to be contaminated with bacteria, fungi, and viruses.

Hydroxyl radical formation

Although nanosized anatase TiO2 does not absorb visible light, it does strongly absorb ultraviolet (UV) radiation (hv), leading to the formation of hydroxyl radicals.[63] This occurs when photo-induced valence bond holes (h+vb) are trapped at the surface of TiO2 leading to the formation of trapped holes (h+tr) that cannot oxidize water.[64]

- TiO2 + hv → e− + h+vb

- h+vb → h+tr

- O2 + e− → O2•−

- O2•− + O2•−+ 2 H+ → H2O2 + O2

- O2•− + h+vb → O2

- O2•− + h+tr → O2

- OH− + h+vb → HO•

- e− + h+tr → recombination

- Note: Wavelength (λ)= 387 nm[64] This reaction has been found to mineralize and decompose undesirable compounds in the environment, specifically the air and in wastewater.[64]Synthetic single crystals of TiO2, ca. 2–3 mm in size, cut from a larger plate.

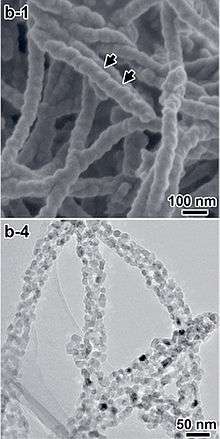

Nanotubes

Anatase can be converted into inorganic nanotubes and nanowires.[65] Hollow TiO2 nanofibers can be also prepared by coating carbon nanofibers by first applying titanium butoxide.[66]

Health and safety

Titanium dioxide is incompatible with strong reducing agents and strong acids.[67] Violent or incandescent reactions occur with molten metals that are electropositive, e.g. aluminium, calcium, magnesium, potassium, sodium, zinc and lithium.[68]

Many sunscreens use nanoparticle titanium dioxide (along with nanoparticle zinc oxide) which, despite reports of potential health risks,[69] is not actually absorbed through the skin.[70] Other effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on human health are not well understood.[71]

Titanium dioxide dust, when inhaled, has been classified by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as an IARC Group 2B carcinogen, meaning it is possibly carcinogenic to humans.[72][73] The findings of the IARC are based on the discovery that high concentrations of pigment-grade (powdered) and ultrafine titanium dioxide dust caused respiratory tract cancer in rats exposed by inhalation and intratracheal instillation.[74] The series of biological events or steps that produce the rat lung cancers (e.g. particle deposition, impaired lung clearance, cell injury, fibrosis, mutations and ultimately cancer) have also been seen in people working in dusty environments. Therefore, the observations of cancer in animals were considered, by IARC, as relevant to people doing jobs with exposures to titanium dioxide dust. For example, titanium dioxide production workers may be exposed to high dust concentrations during packing, milling, site cleaning and maintenance, if there are insufficient dust control measures in place. However, the human studies conducted so far do not suggest an association between occupational exposure to titanium dioxide and an increased risk for cancer. The safety of the use of nano-particle sized titanium dioxide, which can penetrate the body and reach internal organs, has been criticized.[75] Studies have also found that titanium dioxide nanoparticles cause inflammatory response and genetic damage in mice.[76][77] The mechanism by which TiO

2 may cause cancer is unclear. Molecular research suggests that cell cytotoxicity due to TiO

2 results from the interaction between TiO

2 nanoparticles and the lysosomal compartment, independently of the known apoptotic signalling pathways.[78]

The body of research regarding the carcinogenicity of different particle sizes of titanium dioxide has led the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health to recommend two separate exposure limits. NIOSH recommends that fine TiO

2 particles be set at an exposure limit of 2.4 mg/m3, while ultrafine TiO

2 be set at an exposure limit of 0.3 mg/m3, as time-weighted average concentrations up to 10 hours a day for a 40-hour work week.[79] These recommendations reflect the findings in the research literature that show smaller titanium dioxide particles are more likely to pose carcinogenic risk than the larger titanium dioxide particles.

There is some evidence the rare disease yellow nail syndrome may be caused by titanium, either implanted for medical reasons or through eating various foods containing titanium dioxide.[80]

Companies such as Mars and Dunkin' Donuts dropped titanium dioxide from their merchandise in 2015 after public pressure.[81] However, Andrew Maynard, director of Risk Science Center at the University of Michigan, downplayed the supposed danger from use of titanium dioxide in food. He says that the titanium dioxide used by Dunkin' Brands and many other food producers is not a new material, and it is not a nanomaterial either. Nanoparticles are typically smaller than 100 nanometres in diameter, yet most of the particles in food grade titanium dioxide are much larger.[82] Still, size distribution analyses showed that batches of food-grade TiO₂ always comprise a nano-sized fraction as inevitable byproduct of the manufacturing processes.[83]

Environmental waste introduction

Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) is mostly introduced into the environment as nanoparticles via wastewater treatment plants.[84] Cosmetic pigments including titanium dioxide enter the wastewater when the product is washed off into sinks after cosmetic use. Once in the sewage treatment plants, pigments separate into sewage sludge which can then be released into the soil when injected into the soil or distributed on its surface. 99% of these nanoparticles wind up on land rather than in aquatic environments due to their retention in sewage sludge.[84] In the environment, titanium dioxide nanoparticles have low to negligible solubility and have been shown to be stable once particle aggregates are formed in soil and water surroundings.[84] In the process of dissolution, water-soluble ions typically dissociate from the nanoparticle into solution when thermodynamically unstable. TiO2 dissolution increases when there are higher levels of dissolved organic matter and clay in the soil. However, aggregation is promoted by pH at the isoelectric point of TiO2 (pH= 5.8) which renders it neutral and solution ion concentrations above 4.5 mM.[85][86]

National bans on titanium dioxide as a food additive

In 2019, France banned the use of titanium dioxide in food from 2020 on.[87]

Trivia

The exterior of the Saturn V rocket was painted with titanium dioxide; this later allowed astronomers to determine that J002E3 was the S-IVB stage from Apollo 12 and not an asteroid.[88]

See also

- Delustrant

- Dye-sensitized solar cell

- List of inorganic pigments

- Noxer blocks, TiO2-coated pavers that remove NOx pollutants from the air

- Suboxide

- Surface properties of transition metal oxides

- Titanium dioxide nanoparticle

References

- Nowotny, Janusz (2011). Oxide Semiconductors for Solar Energy Conversion: Titanium Dioxide. CRC Press. p. 156. ISBN 9781439848395.

- Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A23. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0617". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- "Titanium" in 2014 Minerals Yearbook. USGS

- "Mineral Commodity Summaries, 2015" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Geological Survey 2015.

- "Mineral Commodity Summaries, January 2016" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Geological Survey 2016.

- Schonbrun, Zach. "The Quest for the Next Billion-Dollar Color". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- El, Goresy; Chen, M; Dubrovinsky, L; Gillet, P; Graup, G (2001). "An ultradense polymorph of rutile with seven-coordinated titanium from the Ries crater". Science. 293 (5534): 1467–70. Bibcode:2001Sci...293.1467E. doi:10.1126/science.1062342. PMID 11520981.

- El Goresy, Ahmed; Chen, Ming; Gillet, Philippe; Dubrovinsky, Leonid; Graup, GüNther; Ahuja, Rajeev (2001). "A natural shock-induced dense polymorph of rutile with α-PbO2 structure in the suevite from the Ries crater in Germany". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 192 (4): 485. Bibcode:2001E&PSL.192..485E. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00480-0.

- Akaogiite. mindat.org

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon Press. pp. 1117–19. ISBN 978-0-08-022057-4.

- Marchand R.; Brohan L.; Tournoux M. (1980). "A new form of titanium dioxide and the potassium octatitanate K2Ti8O17". Materials Research Bulletin. 15 (8): 1129–1133. doi:10.1016/0025-5408(80)90076-8.

- Latroche, M; Brohan, L; Marchand, R; Tournoux (1989). "New hollandite oxides: TiO2(H) and K0.06TiO2". Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 81 (1): 78–82. Bibcode:1989JSSCh..81...78L. doi:10.1016/0022-4596(89)90204-1.

- Akimoto, J.; Gotoh, Y.; Oosawa, Y.; Nonose, N.; Kumagai, T.; Aoki, K.; Takei, H. (1994). "Topotactic Oxidation of Ramsdellite-Type Li0.5TiO2, a New Polymorph of Titanium Dioxide: TiO2(R)". Journal of Solid State Chemistry. 113 (1): 27–36. Bibcode:1994JSSCh.113...27A. doi:10.1006/jssc.1994.1337.

- Simons, P. Y.; Dachille, F. (1967). "The structure of TiO2II, a high-pressure phase of TiO2". Acta Crystallographica. 23 (2): 334–336. doi:10.1107/S0365110X67002713.

- Sato H; Endo S; Sugiyama M; Kikegawa T; Shimomura O; Kusaba K (1991). "Baddeleyite-Type High-Pressure Phase of TiO2". Science. 251 (4995): 786–788. Bibcode:1991Sci...251..786S. doi:10.1126/science.251.4995.786. PMID 17775458.

- Dubrovinskaia N. A.; Dubrovinsky L. S.; Ahuja R.; Prokopenko V. B.; Dmitriev V.; Weber H.-P.; Osorio-Guillen J. M.; Johansson B. (2001). "Experimental and Theoretical Identification of a New High-Pressure TiO2 Polymorph". Phys. Rev. Lett. 87 (27 Pt 1): 275501. Bibcode:2001PhRvL..87A5501D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.275501. PMID 11800890.

- Mattesini M.; de Almeida J. S.; Dubrovinsky L.; Dubrovinskaia L.; Johansson B.; Ahuja R. (2004). "High-pressure and high-temperature synthesis of the cubic TiO2 polymorph". Phys. Rev. B. 70 (21): 212101. Bibcode:2004PhRvB..70u2101M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.70.212101.

- Dubrovinsky, LS; Dubrovinskaia, NA; Swamy, V; Muscat, J; Harrison, NM; Ahuja, R; Holm, B; Johansson, B (2001). "Materials science: The hardest known oxide". Nature. 410 (6829): 653–654. Bibcode:2001Natur.410..653D. doi:10.1038/35070650. hdl:10044/1/11018. PMID 11287944.

- Oganov A.R.; Lyakhov A.O. (2010). "Towards the theory of hardness of materials". Journal of Superhard Materials. 32 (3): 143–147. arXiv:1009.5477. Bibcode:2010arXiv1009.5477O. doi:10.3103/S1063457610030019.

- Al-Khatatbeh, Y.; Lee, K. K. M. & Kiefer, B. (2009). "High-pressure behavior of TiO2 as determined by experiment and theory". Phys. Rev. B. 79 (13): 134114. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..79m4114A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.134114.

- Nishio-Hamane D.; Shimizu A.; Nakahira R.; Niwa K.; Sano-Furukawa A.; Okada T.; Yagi T.; Kikegawa T. (2010). "The stability and equation of state for the cotunnite phase of TiO2 up to 70 GPa". Phys. Chem. Minerals. 37 (3): 129–136. Bibcode:2010PCM....37..129N. doi:10.1007/s00269-009-0316-0.

- Emsley, John (2001). Nature's Building Blocks: An A–Z Guide to the Elements. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 451–53. ISBN 978-0-19-850341-5.

- Banfield, J. F., Veblen, D. R., and Smith, D. J. (1991). "The identification of naturally occurring TiO2 (B) by structure determination using high-resolution electron microscopy, image simulation, and distance–least–squares refinement" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 76: 343.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Alderman, O. L. G., Skinner, L. B., Benmore, C. J., Tamalonis, A., Weber, J. K. R. (2014). "Structure of Molten Titanium Dioxide". Physical Review B. 90 (9): 094204. Bibcode:2014PhRvB..90i4204A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.90.094204.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Titanium dioxide".

- Vartiainen, Jaana (7 October 1998). "Process for preparing titanium dioxide" (PDF).

- Winkler, Jochen (2003). Titanium Dioxide. Hannover: Vincentz Network. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-3-87870-148-4.

- "Top 5 Vendors in the Global Titanium Dioxide Market From 2017-2021: Technavio". 20 April 2017.

- Hayes, Tony (2011). "Titanium Dioxide: A Shining Future Ahead" (PDF). Euro Pacific Canada. p. 5. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- Hayes (2011), p. 3

- Hayes (2011), p. 4

- By Chen, Xiaobo; Mao, Samuel S. (2007). "Titanium Dioxide Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Properties, Modifications, and Applications". Chemical Reviews. 107 (7): 2891–2959. doi:10.1021/cr0500535. PMID 17590053.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Market Study: Titanium Dioxide". Ceresana. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. p. 40. ISBN 9781473630819. OCLC 936144129.

- Anderson, Bruce (1999). Kemira pigments quality titanium dioxide. Savannah, Georgia. p. 39.

- Winkler, Jochen (2003). Titanium Dioxide. Hannover, Germany: Vincentz Network. p. 5. ISBN 978-3-87870-148-4.

- "Deux dentifrices sur trois contiennent du dioxyde de titane, un colorant au possible effet cancérogène". BFMTV.com. 28 March 2019.

- Koleske, J. V. (1995). Paint and Coating Testing Manual. ASTM International. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-8031-2060-0.

- Koleske, J. V. (1995). Paint and Coating Testing Manual. ASTM International. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-8031-2060-0.

- "Pearlescence with Iriodin", pearl-effect.com, archived from the original on 17 January 2012

- Dan, Yongbo et al. Measurement of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles in Sunscreen using Single Particle ICP-MS. perkinelmer.com

- "Health_scientific_committees" (PDF).

- Polymers, Light and the Science of TiO2, DuPont, pp. 1–2

- Liang Chu (2015). "Anatase TiO2 Nanoparticles with Exposed {001} Facets for Efficient Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells". Scientific Reports. 5: 12143. Bibcode:2015NatSR...512143C. doi:10.1038/srep12143. PMC 4507182. PMID 26190140.

- Li Jianming and Dongsheng Xu (2010). "tetragonal faceted-nanorods of anatase TiO2 single crystals with a large percentage of active {100} facets". Chemical Communications. 46 (13): 2301–3. doi:10.1039/b923755k. PMID 20234939.

- M Hussein N Assadi (2016). "The effects of copper doping on photocatalytic activity at (101) planes of anatase TiO 2: A theoretical study". Applied Surface Science. 387: 682–689. arXiv:1811.09157. Bibcode:2016ApSS..387..682A. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.06.178.

- Hanaor, Dorian A. H.; Sorrell, Charles C. (2014). "Sand Supported Mixed-Phase TiO2 Photocatalysts for Water Decontamination Applications". Advanced Engineering Materials. 16 (2): 248–254. arXiv:1404.2652. Bibcode:2014arXiv1404.2652H. doi:10.1002/adem.201300259.

- Kurtoglu M. E.; Longenbach T.; Gogotsi Y. (2011). "Preventing Sodium Poisoning of Photocatalytic TiO2 Films on Glass by Metal Doping". International Journal of Applied Glass Science. 2 (2): 108–116. doi:10.1111/j.2041-1294.2011.00040.x.

- "Discovery and applications of photocatalysis — Creating a comfortable future by making use of light energy". Japan Nanonet Bulletin Issue 44, 12 May 2005.

- Fujishima, Akira; Honda, Kenichi (1972). "Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode". Nature. 238 (5358): 37–8. Bibcode:1972Natur.238...37F. doi:10.1038/238037a0. PMID 12635268.

- "Carbon-doped titanium dioxide is an effective photocatalyst". Advanced Ceramics Report. 1 December 2003. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007.

This carbon-doped titanium dioxide is highly efficient; under artificial visible light, it breaks down chlorophenol five times more efficiently than the nitrogen-doped version.

- Cheap, Clean Ways to Produce Hydrogen for Use in Fuel Cells? A Dash of Disorder Yields a Very Efficient Photocatalyst. Sciencedaily (28 January 2011)

- Karvinen, Saila (2003). "Preparation and Characterization of Mesoporous Visible-Light-Active Anatase". Solid State Sciences. 5 2003 (8): 1159–1166. Bibcode:2003SSSci...5.1159K. doi:10.1016/S1293-2558(03)00147-X.

- Bian, Liang. "Band gap calculation and photo catalytic activity of rare earths doped rutile TiO2". Journal of Rare Earths. 27 2009: 461–468.

- Advanced Concrete Pavement materials Archived 20 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, National Concrete Pavement Technology Center, Iowa State University, p. 435.

- Hogan, Jenny (4 February 2004) "Smog-busting paint soaks up noxious gases". New Scientist.

- TIME's Best Inventions of 2008. (31 October 2008).

- Winkler, Jochen (2003). Titanium Dioxide. Hannover: Vincentz Network. pp. 115–116. ISBN 978-3-87870-148-4.

- Konstantinou, Ioannis K; Albanis, Triantafyllos A (2004). "TiO2-assisted photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes in aqueous solution: Kinetic and mechanistic investigations". Applied Catalysis B: Environmental. 49: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2003.11.010.

- Hanaor, Dorian A. H.; Sorrell, Charles C. (2014). "Sand Supported Mixed-Phase TiO2 Photocatalysts for Water Decontamination Applications". Advanced Engineering Materials. 16 (2): 248–254. arXiv:1404.2652. doi:10.1002/adem.201300259.

- Ramsden, Jeremy J. (2015). "Photocatalytic antimicrobial coatings". Nanotechnology Perceptions. 11 (3): 146–168. doi:10.4024/N12RA15A.ntp.15.03.

- Jones, Tony; Egerton, Terry A. (2000). "Titanium Compounds, Inorganic". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0914151805070518.a01.pub3. ISBN 9780471238966.

- Hirakawa, Tsutomu; Nosaka, Yoshio (23 January 2002). "Properties of O2•-and OH• formed in TiO2 aqueous suspensions by photocatalytic reaction and the influence of H2O2 and some ions". Langmuir. 18 (8): 3247–3254. doi:10.1021/la015685a.

- Mogilevsky, Gregory; Chen, Qiang; Kleinhammes, Alfred; Wu, Yue (2008). "The structure of multilayered titania nanotubes based on delaminated anatase". Chemical Physics Letters. 460 (4–6): 517–520. Bibcode:2008CPL...460..517M. doi:10.1016/j.cplett.2008.06.063.

- Wang, Cui (2015). "Hard-templating of chiral TiO2 nanofibres with electron transition-based optical activity". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 16 (5): 054206. Bibcode:2015STAdM..16e4206W. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/16/5/054206. PMC 5070021. PMID 27877835.

- Occupational Health Services, Inc. (31 May 1988). "Hazardline" (Electronic Bulletin)

|format=requires|url=(help). New York: Occupational Health Services, Inc. - Sax, N.I.; Lewis, Richard J., Sr. (2000). Dangerous Properties of Industrial Materials. III (10th ed.). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. p. 3279. ISBN 978-0-471-35407-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Nano-tech sunscreen presents potential health risk". ABC News. 18 December 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- Sadrieh N, Wokovich AM, Gopee NV, et al. (May 2010). "Lack of significant dermal penetration of titanium dioxide from sunscreen formulations containing nano- and submicron-size TiO2 particles". Toxicol. Sci. 115 (1): 156–66. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfq041. PMC 2855360. PMID 20156837.

- "Nano World: Nanoparticle toxicity tests". Physorg.com. 5 April 2006. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- "Titanium dioxide" (PDF). 93. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Titanium Dioxide Classified as Possibly Carcinogenic to Humans". Canadian Centre for Occupational Health & Safety. August 2006.

- Serpone, Nick; Kutal, Charles (1993). Photosensitive metal-organic systems: mechanistic principles and applications. Columbus, OH: American Chemical Society. ISBN 978-0-8412-2527-5.

- "European chemicals body links titanium dioxide to cancer". Chemistry World. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- "Nanoparticles Used in Common Household Items Cause Genetic Damage in Mice". 17 November 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- Yazdi AS, Guarda G, Riteau N, et al. (November 2010). "Nanoparticles activate the NLR pyrin domain containing 3 (Nlrp3) inflammasome and cause pulmonary inflammation through release of IL-1α and IL-1β". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 (45): 19449–54. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10719449Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1008155107. PMC 2984140. PMID 20974980.

- Zhu Y, Eaton JW, Li C (2012). "Titanium Dioxide (TiO(2)) Nanoparticles Preferentially Induce Cell Death in Transformed Cells in a Bak/Bax-Independent Fashion". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e50607. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750607Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050607. PMC 3503962. PMID 23185639.

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. "Current Intelligence Bulletin 63: Occupational Exposure to Titanium Dioxide (NIOSH Publication No. 2011-160)" (PDF). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

- Berglund F, Carlmark B (October 2011). "Titanium, sinusitis, and the yellow nail syndrome". Biol Trace Elem Res. 143 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1007/s12011-010-8828-5. PMC 3176400. PMID 20809268.

- "Dunkin' Donuts to remove titanium dioxide from donuts". CNN Money. March 2015.

- Dunkin' Donuts ditches titanium dioxide – but is it actually harmful? The Conversation. 12 March 2015

- Critical review of the safety assessment of titanium dioxide additives in food. 1 June 2018

- Tourinho, Paula S.; van Gestel, Cornelis A. M.; Lofts, Stephen; Svendsen, Claus; Soares, Amadeu M. V. M.; Loureiro, Susana (1 August 2012). "Metal-based nanoparticles in soil: Fate, behavior, and effects on soil invertebrates". Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 31 (8): 1679–1692. doi:10.1002/etc.1880. ISSN 1552-8618. PMID 22573562.

- Swiler, Daniel R. (2005). "Pigments, Inorganic". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. doi:10.1002/0471238961.0914151814152215.a01.pub2. ISBN 9780471238966.

- Preočanin, Tajana; Kallay, Nikola (2006). "Point of Zero Charge and Surface Charge Density of TiO2 in Aqueous Electrolyte Solution as Obtained by Potentiometric Mass Titration". Croatica Chemica Acta. 79 (1): 95–106. ISSN 0011-1643.

- France to ban titanium dioxide whitener in food from 2020. Reuters, 2019-04-17

- Jorgensen, K.; Rivkin, A.; Binzel, R.; Whitely, R.; Hergenrother, C.; Chodas, P.; Chesley, S.; Vilas, F. (May 2003). "Observations of J002E3: Possible Discovery of an Apollo Rocket Body". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 35: 981. Bibcode:2003DPS....35.3602J.

External links

| Look up titanium suboxide in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- International Chemical Safety Card 0338

- "Nano-Oxides, Inc. – Nano Powders, LEGIT information on Titanium Dioxide TiO2" (PDF). www.nano-oxides.com.

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards

- The Largest TiO2 Distributor in China Interview with Chairman Yang Tao by ICOAT.CC.

- "Fresh doubt over America map", bbc.co.uk, 30 July 2002

- "Titanium Dioxide Classified as Possibly Carcinogenic to Humans", Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, August, 2006 (if inhaled as a powder)

- A description of TiO2 photocatalysis

- Crystal structures of the three forms of TiO2

- "Architecture in Italy goes green", Elisabetta Povoledo, International Herald Tribune, 22 November 2006

- "A Concrete Step Toward Cleaner Air", Bruno Giussani, BusinessWeek.com, 8 November 2006

- Sunscreen in the Sky? Reflective Particles May Combat Warming

- Titanium and titanium dioxide production data (US and World)