Czech Republic

The Czech Republic (/ˈtʃɛk -/ (![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

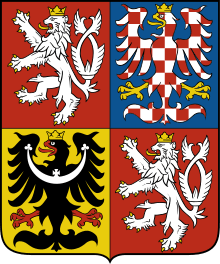

Czech Republic | |

|---|---|

Anthem:

| |

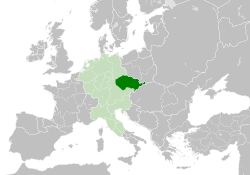

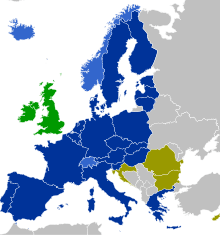

Location of the Czech Republic (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Prague 50°05′N 14°28′E |

| Official language | Czech[1] |

| Officially recognized languages[2][3] | |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion (2011)[6] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Czech |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic |

| Miloš Zeman | |

| Andrej Babiš | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Deputies | |

| Establishment history | |

| c. 870 | |

| 1198 | |

| 28 October 1918 | |

| 1 January 1969 | |

• Czech Republic became independent | 1 January 1993 |

• Joined the European Union | 1 May 2004 |

| Area | |

• Total | 78,866 km2 (30,450 sq mi) (115th) |

• Water (%) | 2 |

| Population | |

• 2020 estimate | |

• 2011 census | 10,436,560[8] |

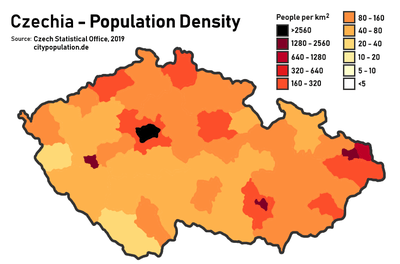

• Density | 134/km2 (347.1/sq mi) (87th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2019) | low · 5th |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 26th |

| Currency | Czech koruna (CZK) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| UTC+2 (CEST) | |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +420b |

| ISO 3166 code | CZ |

| Internet TLD | .czc |

| |

The Czech state was formed in the late 9th century as the Duchy of Bohemia under the Great Moravian Empire. In 1002, the duchy was formally recognized as an Imperial State of the Holy Roman Empire, and became the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1198, reaching its greatest territorial extent in the 14th century.[16][17] Prague was the imperial seat in periods between the 14th and 17th century. The Bohemian Reformation of the 15th century led to the Hussite Wars, which resulted in a period of confessional pluralism and relative religious tolerance.

Following the Battle of Mohács in 1526, the whole Crown of Bohemia was gradually integrated into the Habsburg Monarchy. The Protestant Bohemian Revolt (1618–20) against the Catholic Habsburgs led to the Thirty Years' War. After the Battle of the White Mountain, the Habsburgs consolidated their rule, reimposed Catholicism, and adopted a policy of gradual Germanization. With the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the Bohemian Crown lands became part of the Austrian Empire, and the Czech (Bohemian) language and literature experienced a cultural revival. In the 19th century, the Czech lands became heavily industrialized and were subsequently the core of the First Czechoslovak Republic, which was formed in 1918 following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after World War I.[18]

Czechoslovakia was the only democracy in Central Europe during the interwar period.[19] However, beginning in 1938, Nazi Germany systematically annexed the Czech Lands, while Slovakia became a German puppet state. The country was restored in 1945. Most members of the German-speaking minority were expelled following the war. The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia won a plurality in the 1946 elections and after the 1948 coup d'état established a one-party communist state under Soviet influence. Increasing dissatisfaction with the regime culminated in 1968 to the reform movement known as the Prague Spring, which ended in a Soviet-led invasion. Czechoslovakia remained occupied until the 1989 Velvet Revolution, which peacefully ended communist rule and reestablished democracy with a market economy. On 1 January 1993, Czechoslovakia peacefully dissolved, with its constituent states becoming the independent states of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. The Czech Republic joined NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004. It is also a member of the OECD, the United Nations, the OSCE, and the Council of Europe.

The Czech Republic is a developed country with an advanced, high income social market economy.[20][21][22] It is a welfare state with a European social model, universal health care, and tuition-free university education. It ranks 13th in the UN inequality-adjusted human development and 14th in the World Bank Human Capital Index ahead of countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and France. It ranks as the eleventh safest and most peaceful country and performs well in democratic governance.

Name

- Samo's Empire 631–658

- Great Moravia 830s–907

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

The traditional English name "Bohemia" derives from Latin "Boiohaemum", which means "home of the Boii" (Gallic tribe). The current English name comes from the Polish ethnonym associated with the area, which ultimately comes from the Czech word Čech.[23][24][25] The name comes from the Slavic tribe (Czech: Češi, Čechové) and, according to legend, their leader Čech, who brought them to Bohemia, to settle on Říp Mountain. The etymology of the word Čech can be traced back to the Proto-Slavic root *čel-, meaning "member of the people; kinsman", thus making it cognate to the Czech word člověk (a person).[26]

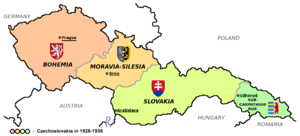

The country has been traditionally divided into three lands, namely Bohemia (Čechy) in the west, Moravia (Morava) in the east, and Czech Silesia (Slezsko; the smaller, south-eastern part of historical Silesia, most of which is located within modern Poland) in the northeast. Known as the lands of the Bohemian Crown since the 14th century, a number of other names for the country have been used, including Czech/Bohemian lands, Bohemian Crown, Czechia[27] and the lands of the Crown of Saint Wenceslas. When the country regained its independence after the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1918, the new name of Czechoslovakia was coined to reflect the union of the Czech and Slovak nations within the one country.

After Czechoslovakia dissolved in 1992, the new Czech state lacked a common English short name. The Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs recommended the English name Czechia in 1993, and the Czech government approved Czechia as the official short name in 2016.[28]

History

Prehistory

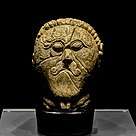

Center: The stone head of a Celt from Mšecké Žehrovice is among the most important artifacts in the archaeological collections of the National Museum in Prague.

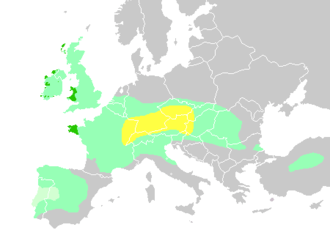

Right: Distribution of Celtic peoples, showing expansion of the core territory in the Czech lands, which were inhabited by the Gallic tribe of Boii

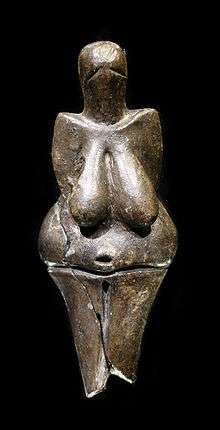

Archaeologists have found evidence of prehistoric human settlements in the area, dating back to the Paleolithic era. The Venus of Dolní Věstonice, dated to 29,000–25,000 BCE, together with a few others from nearby locations, is the oldest known ceramic artifact in the world.

In the classical era, as a result of the 3rd century BC Celtic migrations, Bohemia became associated with the Boii. The Boii founded an oppidum near the site of modern Prague. Later in the 1st century, the Germanic tribes of the Marcomanni and Quadi settled there. Their king Maroboduus is the first documented ruler of Bohemia. During the Migration Period around the 5th century, many Germanic tribes moved westwards and southwards out of Central Europe. Most of the names of Czech rivers are Celtic or old Germanic in origin, dating from usage in those years.

Slavs from the Black Sea–Carpathian region settled in the area (their migration was pushed by an invasion of peoples from Siberia and Eastern Europe into their area: Huns, Avars, Bulgars and Magyars). In the sixth century, they moved westwards into Bohemia, Moravia, and some of present-day Austria and Germany.

During the 7th century, the Frankish merchant Samo, supporting the Slavs fighting against nearby settled Avars, became the ruler of the first known Slavic state in Central Europe, Samo's Empire. The principality of Great Moravia, controlled by Moymir dynasty, arose in the 8th century. It reached its zenith in the 9th (during the reign of Svatopluk I of Moravia), holding off the influence of the Franks. Great Moravia was Christianized, with a crucial role being played by the Byzantine mission of Cyril and Methodius. They created the artificial language Old Church Slavonic, the first literary and liturgical language of the Slavs, and the Glagolitic alphabet.

Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia emerged in the late 9th century, when it was unified by the Přemyslid dynasty. In 10th century Boleslaus I, Duke of Bohemia conquered Moravia, Silesia and expanded farther to the east. The Duchy of Bohemia, raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1198, was from 1002 until 1806 an Imperial State of the Holy Roman Empire alongside the Kingdom of Germany, the Kingdom of Burgundy, the Kingdom of Italy and numerous other territories such as the Old Swiss Confederacy and various Papal States. The kingdom was a significant regional power during the Middle Ages.

In 1212, King Přemysl Ottokar I (bearing the title "king" from 1198) extracted the Golden Bull of Sicily (a formal edict) from the emperor, confirming Ottokar and his descendants' royal status; the Duchy of Bohemia was raised to a Kingdom. The bull declared that the King of Bohemia would be exempt from all future obligations to the Holy Roman Empire except for participation in imperial councils. German immigrants settled in the Bohemian periphery in the 13th century. Germans populated towns and mining districts and, in some cases, formed German colonies in the interior of Bohemia. In 1235, the Mongols launched an invasion of Europe. After the Battle of Legnica in Poland, the Mongols carried their raids into Moravia, but were defensively defeated at the fortified town of Olomouc.[29] The Mongols subsequently invaded and defeated Hungary.[30]

King Přemysl Otakar II earned the nickname Iron and Golden King because of his military power and wealth. He acquired Austria, Styria, Carinthia and Carniola, thus spreading the Bohemian territory to the Adriatic Sea. He met his death at the Battle on the Marchfeld in 1278 in a war with his rival, King Rudolph I of Germany.[31] Ottokar's son Wenceslaus II acquired the Polish crown in 1300 for himself and the Hungarian crown for his son. He built a great empire stretching from the Danube river to the Baltic Sea. In 1306, the last king of Přemyslid line Wenceslaus III was murdered in mysterious circumstances in Olomouc while he was resting. After a series of dynastic wars, the House of Luxembourg gained the Bohemian throne.[32]

The 14th century, in particular, the reign of the Bohemian king Charles IV (1316–1378), who in 1346 became King of the Romans and in 1354 both King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor, is considered the Golden Age of Czech history. Of particular significance was the founding of Charles University in Prague in 1348, Charles Bridge, Charles Square. Much of Prague Castle and the cathedral of Saint Vitus in Gothic style were completed during his reign. He unified Brandenburg (until 1415), Lusatia (until 1635), and Silesia (until 1742) under the Bohemian crown. The Black Death, which had raged in Europe from 1347 to 1352, decimated the Kingdom of Bohemia in 1380,[33] killing about 10% of the population.[34]

.svg.png)

Efforts for a reform of the church in Bohemia started already in the late 14th century with personalities like Milíč of Kroměříž and Matthias of Janov. The most famous figure of the nascent Bohemian Reformation became Jan Hus. Although Hus was named a heretic and burnt in Constance in 1415, his followers (led by warlords Jan Žižka and Prokop the Great) seceded from some practices of the Roman Church and in the Hussite Wars (1419–1434) defeated five crusades organized against them by the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund. During the next two centuries, 90% of the population in Bohemian and Moravian lands were considered Hussites. Hussite George of Podebrady was even a king. Another great thinker of the Bohemian Reformation, Petr Chelčický, inspired the movement of the Bohemian Brethren that completely separated from the Catholic Church (unlike the Hussites). Hus's thoughts were a major influence on the later Lutheranism. Martin Luther himself said "we are all Hussites, without having been aware of it" and considered himself as Hus's direct successor.[35]

After 1526 Bohemia came increasingly under Habsburg control as the Habsburgs became first the elected and then in 1627 the hereditary rulers of Bohemia. The Austrian Habsburgs of the 16th century, the founders of the Central European Habsburg Monarchy, were buried in Prague. Between 1583–1611 Prague was the official seat of the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II and his court.

The Defenestration of Prague and subsequent revolt against the Habsburgs in 1618 marked the start of the Thirty Years' War, which quickly spread throughout Central Europe. In 1620, the rebellion in Bohemia was crushed at the Battle of White Mountain, and the ties between Bohemia and the Habsburgs' hereditary lands in Austria were strengthened. The leaders of the Bohemian Revolt were executed in 1621. The nobility and the middle class Protestants had to either convert to Catholicism or leave the country.[36] This is said to have contributed to anti-Habsburg sentiment and resentment of the Catholic Church that continues to this day.[37][38][39][40]

The following period, from 1620 to the late 18th century, has often been called colloquially the "Dark Age". The population of the Czech lands declined by a third through the expulsion of Czech Protestants as well as due to the war, disease and famine.[41] The Habsburgs prohibited all Christian confessions other than Catholicism.[42] The flowering of Baroque culture shows the ambiguity of this historical period. Ottoman Turks and Tatars invaded Moravia in 1663.[43] In 1679–1680 the Czech lands faced the devastating Great Plague of Vienna and an uprising of serfs.[44]

The reigns of Maria Theresa of Austria and her son Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor and co-regent from 1765, were characterized by enlightened absolutism. In 1740, most of Silesia (except the southernmost area) was seized by King Frederick II of Prussia in the Silesian Wars. In 1757 the Prussians invaded Bohemia and after the Battle of Prague (1757) occupied the city. More than one quarter of Prague was destroyed and St. Vitus Cathedral also suffered heavy damage. Frederick was defeated soon after at the Battle of Kolín and had to leave Prague and retreat from Bohemia. In 1770 and 1771 Great Famine killed about one tenth of the Czech population, or 250,000 inhabitants, and radicalized the countryside leading to peasant uprisings.[45] Serfdom was abolished (in two steps) between 1781 and 1848. Several large battles of the Napoleonic Wars – Battle of Austerlitz, Battle of Kulm – took place on the current territory of the Czech Republic. Joseph Radetzky von Radetz, born to a noble Czech family, was a field marshal and chief of the general staff of the Austrian Empire army during these wars.

The end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 led to degradation of the political status of the Kingdom of Bohemia. Bohemia lost its position of an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire as well as its own political representation in the Imperial Diet.[46] Bohemian lands became part of the Austrian Empire and later of Austria–Hungary. During the 18th and 19th century the Czech National Revival began its rise, with the purpose to revive Czech language, culture and national identity. The Revolution of 1848 in Prague, striving for liberal reforms and autonomy of the Bohemian Crown within the Austrian Empire, was suppressed.[47]

In 1866 Austria was defeated by Prussia in the Austro-Prussian War (see also Battle of Königgrätz and Peace of Prague). The Austrian Empire needed to redefine itself to maintain unity in the face of nationalism. At first it seemed that some concessions would be made also to Bohemia, but in the end the Emperor Franz Joseph I effected a compromise with Hungary only. The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 and the never realized coronation of Franz Joseph as King of Bohemia led to a huge disappointment of Czech politicians.[47] The Bohemian Crown lands became part of the so-called Cisleithania (officially "The Kingdoms and Lands represented in the Imperial Council").

Prague pacifist Bertha von Suttner was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1905. In the same year, the Czech Social Democratic and progressive politicians (including Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk) started the fight for universal suffrage. The first elections under universal male suffrage were held in 1907. The last King of Bohemia was Charles I of Austria who ruled in 1916–1918.

Czechoslovakia

An estimated 1.4 million Czech soldiers fought in World War I, of whom some 150,000 died. Although the majority of Czech soldiers fought for the Austro-Hungarian Empire, more than 90,000 Czech volunteers formed the Czechoslovak Legions in France, Italy and Russia, where they fought against the Central Powers and later against Bolshevik troops.[48] In 1918, during the collapse of the Habsburg Empire at the end of World War I, the independent republic of Czechoslovakia, which joined the winning Allied powers, was created, with Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in the lead.[49] This new country incorporated the Bohemian Crown (Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia) and parts of the Kingdom of Hungary (Slovakia and the Carpathian Ruthenia) with significant German, Hungarian, Polish and Ruthenian speaking minorities.[50] Czechoslovakia concluded a treaty of alliance with Romania and Yugoslavia (the so-called Little Entente) and particularly with France.

The First Czechoslovak Republic comprised only 27% of the population of the former Austria-Hungary, but nearly 80% of the industry, which enabled it to successfully compete with Western industrial states.[51] In 1929 compared to 1913, the gross domestic product increased by 52% and industrial production by 41%. In 1938 Czechoslovakia held 10th place in the world industrial production.[52]

Although the First Czechoslovak Republic was a unitary state, it provided what were at the time rather extensive rights to its minorities and remained the only democracy in this part of Europe in the interwar period. The effects of the Great Depression including high unemployment and massive propaganda from Nazi Germany, however, resulted in discontent and strong support among ethnic Germans for a break from Czechoslovakia.

Adolf Hitler took advantage of this opportunity and using Konrad Henlein's separatist Sudeten German Party, gained the largely German-speaking Sudetenland (and its substantial Maginot Line-like border fortifications) through the 1938 Munich Agreement (signed by Nazi Germany, France, Britain, and Italy). Czechoslovakia was not invited to the conference, and Czechs and Slovaks call the Munich Agreement the Munich Betrayal because France (which had an alliance with Czechoslovakia) and Britain gave up Czechoslovakia instead of facing Hitler, which later proved inevitable.

Despite the mobilization of 1.2 million-strong Czechoslovak army and the Franco-Czech military alliance, Poland annexed the Zaolzie area around Český Těšín; Hungary gained parts of Slovakia and the Subcarpathian Rus as a result of the First Vienna Award in November 1938. The remainders of Slovakia and the Subcarpathian Rus gained greater autonomy, with the state renamed to "Czecho-Slovakia". After Nazi Germany threatened to annex part of Slovakia, allowing the remaining regions to be partitioned by Hungary and Poland, Slovakia chose to maintain its national and territorial integrity, seceding from Czecho-Slovakia in March 1939, and allying itself, as demanded by Germany, with Hitler's coalition.[53]

_crop.jpg)

Right: Edvard Beneš, president before and after World War II.

The remaining Czech territory was occupied by Germany, which transformed it into the so-called Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia. The protectorate was proclaimed part of the Third Reich, and the president and prime minister were subordinated to the Nazi Germany's Reichsprotektor. Subcarpathian Rus declared independence as the Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine on 15 March 1939 but was invaded by Hungary the same day and formally annexed the next day. Approximately 345,000 Czechoslovak citizens, including 277,000 Jews, were killed or executed while hundreds of thousands of others were sent to prisons and Nazi concentration camps or used as forced labor. Up to two-thirds of the citizens were in groups targeted by the Nazis for deportation or death.[54] One concentration camp was located within the Czech territory at Terezín, north of Prague. The Nazi Generalplan Ost called for the extermination, expulsion, Germanization or enslavement of most or all Czechs for the purpose of providing more living space for the German people.[55]

There was Czech resistance to Nazi occupation, both at home and abroad, most notably with the assassination of Nazi German leader Reinhard Heydrich by Czechoslovakian soldiers Jozef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš in a Prague suburb on 27 May 1942. On 9 June 1942 Hitler ordered bloody reprisals against the Czechs as a response to the Czech anti-Nazi resistance. The Edvard Beneš's Czechoslovak government-in-exile and its army fought against the Germans and were acknowledged by the Allies; Czech/Czechoslovak troops fought from the very beginning of the war in Poland, France, the UK, North Africa, the Middle East and the Soviet Union (see I Czechoslovakian Corps). The German occupation ended on 9 May 1945, with the arrival of the Soviet and American armies and the Prague uprising. An estimated 140,000 Soviet soldiers died in liberating Czechoslovakia from German rule.[56]

_Squadron_RAF_in_front_of_Hawker_Hurricane_Mk_I_at_Duxford%2C_Cambridgeshire%2C_7_September_1940._CH1299.jpg)

In 1945–1946, almost the entire German-speaking minority in Czechoslovakia, about 3 million people, were expelled to Germany and Austria (see also Beneš decrees). During this time, thousands of Germans were held in prisons and detention camps or used as forced labor. In the summer of 1945, there were several massacres, such as the Postoloprty massacre. Research by a joint German and Czech commission of historians in 1995 found that the death toll of the expulsions was at least 15,000 persons and that it could range up to a maximum of 30,000 dead.[57] The only Germans not expelled were some 250,000 who had been active in the resistance against the Nazi Germans or were considered economically important, though many of these emigrated later. Following a Soviet-organized referendum, the Subcarpathian Rus never returned under Czechoslovak rule but became part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, as the Zakarpattia Oblast in 1946.

Czechoslovakia uneasily tried to play the role of a "bridge" between the West and East. However, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia rapidly increased in popularity, with a general disillusionment with the West, because of the pre-war Munich Agreement, and a favourable popular attitude towards the Soviet Union, because of the Soviets' role in liberating Czechoslovakia from German rule. In the 1946 elections, the Communists gained 38%[58] of the votes and became the largest party in the Czechoslovak parliament. They formed a coalition government with other parties of the National Front and moved quickly to consolidate power. A significant change came in 1948 with coup d'état by the Communist Party. The Communist People's Militias secured control of key locations in Prague, and a single party government was formed.

For the next 41 years, Czechoslovakia was a Communist state within the Eastern Bloc. This period is characterized by lagging behind the West in almost every aspect of social and economic development. The country's GDP per capita fell from the level of neighboring Austria to below that of Greece or Portugal in the 1980s. The Communist government completely nationalized the means of production and established a command economy. The economy grew rapidly during the 1950s but slowed down in the 1960s and 1970s and stagnated in the 1980s.

The political climate was highly repressive during the 1950s, including numerous show trials (the most famous victims: Milada Horáková and Rudolf Slánský) and hundreds of thousands of political prisoners, but became more open and tolerant in the late 1960s, culminating in Alexander Dubček's leadership in the 1968 Prague Spring, which tried to create "socialism with a human face" and perhaps even introduce political pluralism. This was forcibly ended by invasion by all Warsaw Pact member countries with the exception of Romania and Albania on 21 August 1968. Student Jan Palach became a symbol of resistance to the occupation, when he committed self-immolation as a political protest.

The invasion was followed by a harsh program of "Normalization" in the late 1960s and the 1970s. Until 1989, the political establishment relied on censorship of the opposition. Dissidents published Charter 77 in 1977, and the first of a new wave of protests were seen in 1988. Between 1948 and 1989 about 250,000 Czechs and Slovaks were sent to prison for political reasons, and over 400,000 emigrated.[59]

Velvet Revolution and the European Union

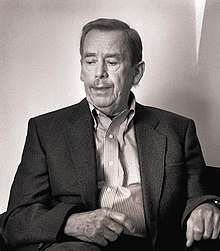

In November 1989, Czechoslovakia returned to a liberal democracy through the peaceful "Velvet Revolution" (led by Václav Havel and his Civic Forum). However, Slovak national aspirations strengthened (see Hyphen War) and on 1 January 1993, the country peacefully split into the independent countries of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Both countries went through economic reforms and privatisations, with the intention of creating a market economy. This process was largely successful; in 2006 the Czech Republic was recognized by the World Bank as a "developed country",[20] and in 2009 the Human Development Index ranked it as a nation of "Very High Human Development".[60]

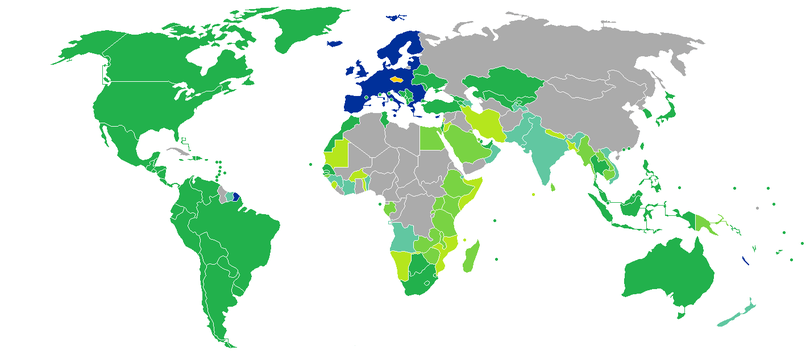

From 1991, the Czech Republic, originally as part of Czechoslovakia and since 1993 in its own right, has been a member of the Visegrád Group and from 1995, the OECD. The Czech Republic joined NATO on 12 March 1999 and the European Union on 1 May 2004. On 21 December 2007 the Czech Republic joined the Schengen Area. Until 2017, either the Social Democrats (under Miloš Zeman, Vladimír Špidla, Stanislav Gross, Jiří Paroubek and Bohuslav Sobotka), or liberal-conservatives (under Václav Klaus, Mirek Topolánek and Petr Nečas) led the government of the Czech Republic.

Geography

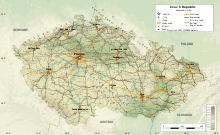

The Czech Republic lies mostly between latitudes 48° and 51° N (a small area lies north of 51°), and longitudes 12° and 19° E.

The Czech landscape is exceedingly varied. Bohemia, to the west, consists of a basin drained by the Elbe (Czech: Labe) and the Vltava rivers, surrounded by mostly low mountains, such as the Krkonoše range of the Sudetes. The highest point in the country, Sněžka at 1,603 m (5,259 ft), is located here. Moravia, the eastern part of the country, is also quite hilly. It is drained mainly by the Morava River, but it also contains the source of the Oder River (Czech: Odra).

Water from the Czech Republic flows to three different seas: the North Sea, Baltic Sea and Black Sea. The Czech Republic also leases the Moldauhafen, a 30,000-square-meter (7.4-acre) lot in the middle of the Hamburg Docks, which was awarded to Czechoslovakia by Article 363 of the Treaty of Versailles, to allow the landlocked country a place where goods transported down river could be transferred to seagoing ships. The territory reverts to Germany in 2028.

Phytogeographically, the Czech Republic belongs to the Central European province of the Circumboreal Region, within the Boreal Kingdom. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, the territory of the Czech Republic can be subdivided into four ecoregions: the Western European broadleaf forests, Central European mixed forests, Pannonian mixed forests, and Carpathian montane conifer forests.

There are four national parks in the Czech Republic. The oldest is Krkonoše National Park (Biosphere Reserve), and the others are Šumava National Park (Biosphere Reserve), Podyjí National Park, Bohemian Switzerland.

The three historical lands of the Czech Republic (formerly the core countries of the Bohemian Crown) correspond almost perfectly with the river basins of the Elbe (Czech: Labe) and the Vltava basin for Bohemia, the Morava one for Moravia, and the Oder river basin for Czech Silesia (in terms of the Czech territory).

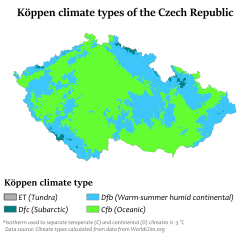

Climate

The Czech Republic mostly has a temperate oceanic climate, with warm summers and cold, cloudy and snowy winters. The temperature difference between summer and winter is relatively high, due to the landlocked geographical position.[61]

Within the Czech Republic, temperatures vary greatly, depending on the elevation. In general, at higher altitudes, the temperatures decrease and precipitation increases. The wettest area in the Czech Republic is found around Bílý Potok in Jizera Mountains and the driest region is the Louny District to the northwest of Prague. Another important factor is the distribution of the mountains; therefore, the climate is quite varied.

At the highest peak of Sněžka (1,603 m or 5,259 ft), the average temperature is only −0.4 °C (31 °F), whereas in the lowlands of the South Moravian Region, the average temperature is as high as 10 °C (50 °F). The country's capital, Prague, has a similar average temperature, although this is influenced by urban factors.

The coldest month is usually January, followed by February and December. During these months, there is usually snow in the mountains and sometimes in the major cities and lowlands. During March, April, and May, the temperature usually increases rapidly, especially during April, when the temperature and weather tends to vary widely during the day. Spring is also characterized by high water levels in the rivers, due to melting snow with occasional flooding.

The warmest month of the year is July, followed by August and June. On average, summer temperatures are about 20 °C (36 °F) – 30 °C (54 °F) higher than during winter. Summer is also characterized by rain and storms.

Autumn generally begins in September, which is still relatively warm and dry. During October, temperatures usually fall below 15 °C (59 °F) or 10 °C (50 °F) and deciduous trees begin to shed their leaves. By the end of November, temperatures usually range around the freezing point.

The coldest temperature ever measured was in Litvínovice near České Budějovice in 1929, at −42.2 °C (−44.0 °F) and the hottest measured, was at 40.4 °C (104.7 °F) in Dobřichovice in 2012.[62]

Most rain falls during the summer. Sporadic rainfall is relatively constant throughout the year (in Prague, the average number of days per month experiencing at least 0.1 mm (0.0039 in) of rain varies from 12 in September and October to 16 in November) but concentrated heavy rainfall (days with more than 10 mm (0.39 in) per day) are more frequent in the months of May to August (average around two such days per month).[63] Severe thunderstorms, producing damaging straight-line winds, hail, and even occasional tornadoes occur, especially during the summer period.[64][65]

Environment

The Czech Republic ranks as the 27th most environmentally conscious country in the world in Environmental Performance Index.[66] The Czech Republic has four National Parks (Šumava National Park, Krkonoše National Park, České Švýcarsko National Park, Podyjí National Park) and 25 Protected Landscape Areas.

Government and politics

The Czech Republic is a pluralist multi-party parliamentary representative democracy, with the President as head of state and Prime Minister as head of government. The Parliament (Parlament České republiky) is bicameral, with the Chamber of Deputies (Czech: Poslanecká sněmovna) (200 members) and the Senate (Czech: Senát) (81 members).[67]

The president is a formal head of state with limited and specific powers, most importantly to return bills to the parliament, appoint members to the board of the Czech National Bank, nominate constitutional court judges for the Senate's approval and dissolve the Chamber of Deputies under certain special and unusual circumstances. The president and vice president of the Supreme Court are appointed by the President of the Republic. He also appoints the prime minister, as well the other members of the cabinet on a proposal by the prime minister. From 1993 until 2012, the President of the Czech Republic was selected by a joint session of the parliament for a five-year term, with no more than two consecutive terms (2x Václav Havel, 2x Václav Klaus). Since 2013 the presidential election is direct.[68] Miloš Zeman was the first directly elected Czech President.

The Government of the Czech Republic's exercise of executive power derives from the Constitution. The members of the government are the Prime Minister, Deputy prime ministers and other ministers. The Government is responsible to the Chamber of Deputies.[69]

The Prime Minister is the head of government and wields considerable powers, such as the right to set the agenda for most foreign and domestic policy and choose government ministers.[70] The current Prime Minister of the Czech Republic is Andrej Babiš, serving since 6 December 2017 as the 12th Prime Minister.

The members of the Chamber of Deputies are elected for a four-year term by proportional representation, with a 5% election threshold. There are 14 voting districts, identical to the country's administrative regions. The Chamber of Deputies, the successor to the Czech National Council, has the powers and responsibilities of the now defunct federal parliament of the former Czechoslovakia.

The members of the Senate are elected in single-seat constituencies by two-round runoff voting for a six-year term, with one-third elected every even year in the autumn. The first election was in 1996, for differing terms. This arrangement is modeled on the U.S. Senate, but each constituency is roughly the same size and the voting system used is a two-round runoff.

| Office | Name | Party | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| President | Miloš Zeman | SPOZ | 8 March 2013 |

| President of the Senate | Miloš Vystrčil | ODS | 19 February 2020 |

| Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies | Radek Vondráček | ANO | 22 November 2017 |

| Prime Minister | Andrej Babiš | ANO | 6 December 2017 |

Law

The Czech Republic is a unitary state with a civil law system based on the continental type, rooted in Germanic legal culture. The basis of the legal system is the Constitution of the Czech Republic adopted in 1993. The Penal Code is effective from 2010. A new Civil code became effective in 2014. The court system includes district, county and supreme courts and is divided into civil, criminal, and administrative branches. The Czech judiciary has a triumvirate of supreme courts. The Constitutional Court consists of 15 constitutional judges and oversees violations of the Constitution by either the legislature or by the government. The Supreme Court is formed of 67 judges and is the court of highest appeal for almost all legal cases heard in the Czech Republic. The Supreme Administrative Court decides on issues of procedural and administrative propriety. It also has jurisdiction over many political matters, such as the formation and closure of political parties, jurisdictional boundaries between government entities, and the eligibility of persons to stand for public office. The Supreme Court and the Supreme Administrative Court are both based in Brno, as is the Supreme Public Prosecutor's Office.

Foreign relations

The Czech Republic ranks as the 11th safest or most peaceful country. It is a member of the United Nations, the European Union, NATO, OECD, Council of Europe and is an observer to the Organization of American States.[71] The embassies of most countries with diplomatic relations with the Czech Republic are located in Prague, while consulates are located across the country.

The Czech passport is one of the least restricted by visas. According to the 2018 Henley & Partners Visa Restrictions Index, Czech citizens have visa-free access to 173 countries, which ranks them 7th along with Malta and New Zealand.[72] The World Tourism Organization ranks the Czech passport 24th.[73] The US Visa Waiver Program applies to Czech nationals.

The Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs have primary roles in setting foreign policy, although the President has considerable influence and also represents the country abroad. Membership in the European Union and NATO is central to the Czech Republic's foreign policy. The Office for Foreign Relations and Information (ÚZSI) serves as the foreign intelligence agency responsible for espionage and foreign policy briefings, as well as protection of Czech Republic's embassies abroad.

The Czech Republic has strong ties with Slovakia, Poland and Hungary as a member of the Visegrad Group,[74] as well as with Germany,[75] Israel,[76] the United States[77] and the European Union and its members.

Czech officials have supported dissenters in Belarus, Moldova, Myanmar and Cuba.[78]

Military

The Czech armed forces consist of the Czech Land Forces, the Czech Air Force and of specialized support units. The armed forces are managed by the Ministry of Defence. The President of the Czech Republic is Commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In 2004 the army transformed itself into a fully professional organization and compulsory military service was abolished. The country has been a member of NATO since 12 March 1999. Defence spending is approximately 1.19% of the GDP (2019).[79] The armed forces are charged with protecting the Czech Republic and its allies, promoting global security interests, and contributing to NATO.

Currently, as a member of NATO, the Czech military are participating in the Resolute Support and KFOR operations and have soldiers in Afghanistan, Mali, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Egypt, Israel and Somalia. The Czech Air Force also served in the Baltic states and Iceland.[80] The main equipment of the Czech military includes JAS 39 Gripen multi-role fighters, Aero L-159 Alca combat aircraft, Mi-35 attack helicopters, armored vehicles (Pandur II, OT-64, OT-90, BVP-2) and tanks (T-72 and T-72M4CZ).

Administrative divisions

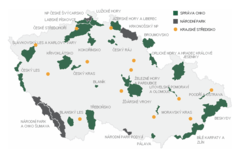

Since 2000, the Czech Republic has been divided into thirteen regions (Czech: kraje, singular kraj) and the capital city of Prague. Every region has its own elected regional assembly (krajské zastupitelstvo) and hejtman (a regional governor). In Prague, the assembly and presidential powers are executed by the city council and the mayor.

The older seventy-six districts (okresy, singular okres) including three "statutory cities" (without Prague, which had special status) lost most of their importance in 1999 in an administrative reform; they remain as territorial divisions and seats of various branches of state administration.[81]

.png)

| Licence plate letter |

Region name in English |

Region name in Czech |

Administrative seat |

Population (2004 estimate) |

Population (2011 estimate)[82] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Hlavní město Praha | n/a | 1,170,571 | 1,268,796 | |

| S | Středočeský kraj | Pragueb | 1,144,071 | 1,289,211 | |

| C | Jihočeský kraj | České Budějovice | 625,712 | 628,336 | |

| P | Plzeňský kraj | Plzeň | 549,618 | 570,401 | |

| K | Karlovarský kraj | Karlovy Vary | 304,588 | 295,595 | |

| U | Ústecký kraj | Ústí nad Labem | 822,133 | 835,814 | |

| L | Liberecký kraj | Liberec | 427,563 | 432,439 | |

| H | Královéhradecký kraj | Hradec Králové | 547,296 | 547,916 | |

| E | Pardubický kraj | Pardubice | 505,285 | 511,627 | |

| M | Olomoucký kraj | Olomouc | 635,126 | 628,427 | |

| T | Moravskoslezský kraj | Ostrava | 1,257,554 | 1,205,834 | |

| B | Jihomoravský kraj | Brno | 1,123,201 | 1,163,508 | |

| Z | Zlínský kraj | Zlín | 590,706 | 579,944 | |

| J | Kraj Vysočina | Jihlava | 517,153 | 505,565 |

a Capital city.

b Office location.

Economy

The Czech Republic has a developed,[83] high-income[84] export-oriented social market economy based in services, manufacturing and innovation, that maintains a welfare state and the European social model.[85] The Czech Republic participates in the European Single Market as a member of the European Union, and is therefore a part of the economy of the European Union, but uses its own currency, the Czech koruna, instead of the euro. It has a per capita GDP rate that is 91% of the EU average[86] and is a member of the OECD. Monetary policy is conducted by the Czech National Bank, whose independence is guaranteed by the Constitution. The Czech Republic ranks 13th in the UN inequality-adjusted human development and 14th in World Bank Human Capital Index ahead of countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and France. It was described by The Guardian as "one of Europe’s most flourishing economies".[87]

As of 2018, the country's GDP per capita at purchasing power parity is $37,370 (similar to Israel, Italy or Slovenia)[88] and $22,850 at nominal value.[89] According to Allianz A.G., in 2018 the country was an MWC (mean wealth country), ranking 26th in net financial assets.[90] The country experienced a 4.5% GDP growth in 2017, giving the Czech economy one of the highest growth rates in the European Union.[91] The 2016 unemployment rate was the lowest in the EU at 2.4%,[92] and the 2016 poverty rate was the second lowest of OECD members behind only Denmark.[93] Czech Republic ranks 24th in both the Index of Economic Freedom[94] and the Global Innovation Index as of 2016,[95] 29th in the Global Competitiveness Report[96] 30th in the ease of doing business index and 25th in the Global Enabling Trade Report.[97] The Czech Republic has a highly diverse economy that ranks 7th in the 2016 Economic Complexity Index.[98] The industrial sector accounts for 37.5% of the economy, while services account for 60% and agriculture for 2.5%.[99] The largest trading partner for both export and import is Germany and the EU in general. Dividends worth CZK 270 billion were paid to the foreign owners of Czech companies in 2017, which has become a political issue in the Czech Republic.[100] The country has been a member of the Schengen Area since 1 May 2004, having abolished border controls, completely opening its borders with all of its neighbors (Germany, Austria, Poland and Slovakia) on 21 December 2007.[101] The Czech Republic became a member of the World Trade Organization on 1 January 1995.

Industry

In 2018 the largest companies by revenue in the Czech Republic were: one of the largest car automobile manufacturers in Central Europe Škoda Auto, utility company ČEZ Group, conglomerate Agrofert, energy trading company EPH, oil processing company Unipetrol, electronics manufacturer Foxconn CZ and steel producer Moravia Steel.[102] Other Czech transportation companies include: Škoda Transportation (tramways, trolleybuses, metro), Tatra (heavy trucks, the second oldest car maker in the world), Avia (medium trucks), Karosa and SOR Libchavy (buses), Aero Vodochody (military aircraft), Let Kunovice (civil aircraft), Zetor (tractors), Jawa Moto (motorcycles) and Čezeta (electric scooters).

Škoda Transportation is the fourth largest tramway producer in the world; nearly one third of all trams in the world come from Czech factories.[103] The Czech Republic is also the world's largest vinyl records manufacturer, with GZ Media producing about 6 million pieces annually in Loděnice.[104] Česká zbrojovka is among the ten largest firearms producers in the world and five who produce automatic weapons.[105]

In the food industry succeeded companies Agrofert, Kofola, Hamé and Bageterie Boulevard.

Energy

Production of Czech electricity exceeds consumption by about 10 TWh per year, which are exported. Nuclear power presently provides about 30 percent of the total power needs, its share is projected to increase to 40 percent. In 2005, 65.4 percent of electricity was produced by steam and combustion power plants (mostly coal); 30 percent by nuclear plants; and 4.6 percent from renewable sources, including hydropower. The largest Czech power resource is Temelín Nuclear Power Station, another nuclear power plant is in Dukovany.

The Czech Republic is reducing its dependence on highly polluting low-grade brown coal as a source of energy. Natural gas is procured from Russian Gazprom, roughly three-fourths of domestic consumption and from Norwegian companies, which make up most of the remaining one-fourth. Russian gas is imported via Ukraine, Norwegian gas is transported through Germany. Gas consumption (approx. 100 TWh in 2003–2005) is almost double electricity consumption. South Moravia has small oil and gas deposits.

Transportation infrastructure

The road network in the Czech Republic is 55,653 km (34,581.17 mi) long.[106] There are 1,232 km of motorways as of 2017.[107] The speed limit is 50 km/h within towns, 90 km/h outside of towns and 130 km/h on motorways.[108]

The Czech Republic has the densest rail network in the world[109] with 9,505 km (5,906.13 mi) of tracks.[110] Of that number, 2,926 km (1,818.13 mi) is electrified, 7,617 km (4,732.98 mi) are single-line tracks and 1,866 km (1,159.48 mi) are double and multiple-line tracks.[111] České dráhy (the Czech Railways) is the main railway operator in the Czech Republic, with about 180 million passengers carried yearly. Maximum speed is limited to 160 km/h. In 2006 seven Italian tilting trainsets Pendolino ČD Class 680 entered service.

Václav Havel Airport in Prague is the main international airport in the country. In 2017, it handled 15 million passengers, which makes it the one of the busiest airports in Central Europe. In total, the Czech Republic has 46 airports with paved runways, six of which provide international air services in Brno, Karlovy Vary, Mošnov (near Ostrava), Pardubice, Prague and Kunovice (near Uherské Hradiště).

Russia, via pipelines through Ukraine and to a lesser extent, Norway, via pipelines through Germany, supply the Czech Republic with liquid and natural gas.[112]

Communications and IT

The Czech Republic ranks in the top 10 countries worldwide with the fastest average internet speed.[113] By the beginning of 2008, there were over 800 mostly local WISPs,[114][115] with about 350,000 subscribers in 2007. Plans based on either GPRS, EDGE, UMTS or CDMA2000 are being offered by all three mobile phone operators (T-Mobile, O2, Vodafone) and internet provider U:fon. Government-owned Český Telecom slowed down broadband penetration. At the beginning of 2004, local-loop unbundling began and alternative operators started to offer ADSL and also SDSL. This and later privatisation of Český Telecom helped drive down prices.

On 1 July 2006, Český Telecom was acquired by globalized company (Spain-owned) Telefónica group and adopted the new name Telefónica O2 Czech Republic. As of 2017, VDSL and ADSL2+ are offered in many variants, with download speeds of up to 50 Mbit/s and upload speeds of up to 5 Mbit/s. Cable internet is gaining popularity with its higher download speeds ranging from 50 Mbit/s to 1 Gbit/s.

Two major computer security companies, Avast and AVG, were founded in the Czech Republic. In 2016, Avast led by Pavel Baudiš bought rival AVG for US$1.3 billion, together at the time, these companies had a user base of about 400 million people and 40% of the consumer market outside of China.[116][117] Avast is the leading provider of antivirus software, with a 20.5% market share.[118]

Science and philosophy

The Czech lands have a long and rich scientific tradition. The research based on cooperation between universities, Academy of Sciences and specialized research centers brings new inventions and impulses in this area. Important contributions include the modern contact lens, the separation of blood types, the basic theory of genetics, many advances in nanotechnologies and the production of Semtex plastic explosive.

Humanities

Cyril and Methodius laid the foundations of education and the Czech theological thinking in the 9th century. Original theological and philosophical stream – Hussitism – originated in the Middle Ages. It was represented by Jan Hus, Jerome of Prague or Petr Chelčický. At the end of the Middle Ages, Jan Amos Comenius substantially contributed to the development of modern pedagogy. Jewish philosophy in the Czech lands was represented mainly by Judah Loew ben Bezalel (known for the legend of the Golem of Prague). Bernard Bolzano was the personality of German-speaking philosophy in the Czech lands. Bohuslav Balbín was a key Czech philosopher and historian of the Baroque era. He also started the struggle for rescuing the Czech language. This culminated in the Czech national revival in the first half of the 19th century. Linguistics (Josef Dobrovský, Pavel Jozef Šafařík, Josef Jungmann), ethnography (Karel Jaromír Erben, František Ladislav Čelakovský) and history (František Palacký) played a big role in revival. Palacký was the eminent personality. He wrote the first synthetic history of the Czech nation. He was also the first Czech modern politician and geopolitician (see also Austro-Slavism). He is often called "The Father of the Nation".

In the second half of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century there was a huge development of social sciences. Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk laid the foundations of Czech sociology. Konstantin Jireček founded Byzantology (see also Jireček Line). Alois Musil was a prominent orientalist, Emil Holub ethnographer. Lubor Niederle was a founder of modern Czech archeology. Sigmund Freud established psychoanalysis. Edmund Husserl defined a new philosophical doctrine – phenomenology. Joseph Schumpeter brought genuine economic ideas of "creative destruction" of capitalism. Hans Kelsen was significant legal theorist. Karl Kautsky influenced the history of Marxism. On the contrary, economist Eugen Böhm von Bawerk led a campaign against Marxism. Max Wertheimer was one of the three founders of Gestalt psychology. Musicologists Eduard Hanslick and Guido Adler influenced debates on the development of classical music in Vienna.

The new Czechoslovak republic (1918–1938) wanted to develop sciences. Significant linguistic school was established in Prague – Prague Linguistic Circle (Vilém Mathesius, Jan Mukařovský, René Wellek), moreover linguist Bedřich Hrozný deciphered the ancient Hittite language and linguist Julius Pokorny deepened knowledge about Celtic languages. Philosopher Herbert Feigl was a member of the Vienna Circle. Ladislav Klíma has developed a special version of Nietzschean philosophy. In the second half of the 20th century can be mentioned philosopher Ernest Gellner who is considered one of the leading theoreticians on the issue of nationalism. Also Czech historian Miroslav Hroch analyzed modern nationalism. Vilém Flusser developed the philosophy of technology and image. Marxist Karel Kosík was a major philosopher in the background of the Prague Spring 1968. Jan Patočka and Václav Havel were the main ideologists of the Charter 77. Egon Bondy was a major philosophical spokesman of the Czech underground in the 1970s and 1980s. Czech Egyptology has scored some successes, its main representative is Miroslav Verner. Czech psychologist Stanislav Grof developed a method of "Holotropic Breathwork". Experimental archaeologist Pavel Pavel made several attempts, they had to answer the question how ancient civilizations transported heavy weights.

Science and technology

Famous scientists who were born on the territory of the current Czech Republic:

- Friedrich von Berchtold (1781–1876), botanist, an avid worker for Czech national revival.

- Wenceslas Bojer (1795–1856), naturalist and botanist.

- Stanislav Brebera (1925–2012), inventor of the plastic explosive Semtex in 1966.[119]

- Josef Čapek (1887–1945) and Karel Čapek (1890–1938), brothers who originated the word robot, for drama R.U.R.

- Eduard Čech (1893–1960), mathematician with significant contributions in topology.

- Václav Prokop Diviš (1698–1765), inventor of the first grounded lightning rod.

- Karel Domin (1882–1953), botanist, specialist in Australian taxonomy

- František Josef Gerstner (1756–1832), physicist and engineer, built the first iron works and the first steam engine in Czech lands.

- Gerty and Carl Cori – Nobel Prize laureates in Physiology or Medicine 1947.

- Kurt Gödel (1906–1978) logician and mathematician, who became famous for his two incompleteness theorems.

- Peter Grünberg (born 1939) Nobel Prize laureate in Physics 2007.

- Jaroslav Heyrovský (1890–1967), inventor of polarography, electroanalytical chemistry and recipient of the Nobel Prize.[120]

- Josef Hlavka (15 February 1831 – 11 March 1908), was a Czech architect, builder, philanthropist and founder of the oldest Czech foundation for sciences and arts.

- Antonín Holý (1936–2012), scientist and chemist, in 2009 was involved in creation of the most effective drug in the treatment of AIDS.[121]

- Jakub Husník (1837–1916), improved the process of photolithography.

- Jan Janský (1873–1921), serologist and neurologist, discovered the ABO blood groups.

- Georg Joseph Kamel (1661–1706), Czech Jesuit, pharmacist and naturalist known for producing first comprehensive accounts of the Philippine flora; genus of flowering plants Camellia is named in his honor.

- Karel Klíč (1841–1926), painter and photographer, inventor of the photogravure.

- František Křižík (1847–1941), electrical engineer, inventor of the arc lamp.

- Julius Vincenz von Krombholz (1782–1843), biologist, founder of the great tradition of Czech mycology.

- Johann Josef Loschmidt (1821–1895), chemist, performed ground-breaking work in crystal forms.

- Ernst Mach (1838–1916) physicist and critic of Newton's theories of space and time, foreshadowing Einstein's theory of relativity.

- Jan Marek Marci (1595–1667), mathematician, physicist and imperial physician, one of the founders of spectroscopy.[122]

- Christian Mayer (1719–1783), astronomer, pioneer in the study of binary stars.

- Gregor Mendel (1822–1884), often called the "father of genetics", is famed for his research concerning the inheritance of genetic traits.[120]

- Johann Palisa (1848–1925), astronomer who discovered 122 asteroids

- Ferdinand Porsche (1875–1951), automotive designer.

- Carl Borivoj Presl (1794–1852) and Jan Svatopluk Presl (1791–1849), brothers, both prominent botanists.

- Jan Evangelista Purkyně (1787–1869), anatomist and physiologist responsible for the discovery of Purkinje cells, Purkinje fibres and sweat glands, as well as Purkinje images and the Purkinje shift.

- Jakub Kryštof Rad (1799–1871), inventor of sugar cubes.

- Vladimír Remek was the first person outside of the Soviet Union and the United States to go into space (in March 1978).

- Josef Ressel (1793–1857), inventor of the screw propeller and modern compass.[120]

- Carl von Rokitansky (1804–1878), Joseph Škoda (1805–1881) and Ferdinand Ritter von Hebra (1816–1880), Czech doctors and founders of the Modern Medical School of Vienna.

- Heinrich Wilhelm Schott (1794–1865), botanist well known for his extensive work on aroids.

- Alois Senefelder (1771–1834), inventor of lithographic printing.

- Zdenko Hans Skraup (1850–1910), chemist who discovered the Skraup reaction, the first quinoline synthesis.

- Kaspar Maria von Sternberg (1761–1838), mineralogist, founder of the Bohemian National Museum in Prague.

- Ferdinand Stoliczka (1838–1874), palaeontologist who died of high altitude sickness during an expedition across the Himalayas.

- Karl von Terzaghi (1883–1963), geologist known as the "father of soil mechanics".

- Hans Tropsch (1889–1935), chemist responsible for the development of the Fischer-Tropsch process.

- Otto Wichterle (1913–1998) and Drahoslav Lím (1925–2003), Czech chemists responsible for the invention of the modern contact lens and silon (synthetic fiber).[123]

- Johannes Widmann (1460–1498), mathematician, inventor of the + and − symbols.

A number of other scientists are also connected in some way with the Czech lands. The following taught at the University of Prague: astronomers Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe, physicists Christian Doppler, Nikola Tesla, and Albert Einstein, and geologist Joachim Barrande.

Tourism

.jpg)

The Czech economy gets a substantial income from tourism. Prague is the fifth most visited city in Europe after London, Paris, Istanbul and Rome.[124] In 2001, the total earnings from tourism reached 118 billion CZK, making up 5.5% of GNP and 9% of overall export earnings. The industry employs more than 110,000 people – over 1% of the population.[125] The country's reputation has suffered with guidebooks and tourists reporting overcharging by taxi drivers and pickpocketing problems mainly in Prague, though the situation has improved recently.[126][127] Since 2005, Prague's mayor, Pavel Bém, has worked to improve this reputation by cracking down on petty crime[127] and, aside from these problems, Prague is a safe city.[128] Also, the Czech Republic as a whole generally has a low crime rate.[129] For tourists, the Czech Republic is considered a safe destination to visit. The low crime rate makes most cities and towns very safe to walk around.

One of the most visited tourist attractions in the Czech Republic[130] is the Nether district Vítkovice in Ostrava, a post-industrial city in the east within the country. The territory was formerly the site of steel production, but now it hosts a technical museum with many interactive expositions for tourists.

The Czech Republic boasts 14 UNESCO World Heritage Sites. All of them are in the cultural category. As of 2018, further 18 sites are on the tentative list.[131]

There are several centres of tourist activity. The spa towns, such as Karlovy Vary, Mariánské Lázně and Františkovy Lázně and Jáchymov, are particularly popular relaxing holiday destinations. Architectural heritage is another object of interest to visitors – it includes many castles and châteaux from different historical epoques, namely Karlštejn Castle, Český Krumlov and the Lednice–Valtice area.

There are 12 cathedrals and 15 churches elevated to the rank of basilica by the Pope, calm monasteries, many modern and ancient churches – for example Pilgrimage Church of Saint John of Nepomuk is one of those inscribed on the World Heritage List. Away from the towns, areas such as Český ráj, Šumava and the Krkonoše Mountains attract visitors seeking outdoor pursuits.

The country is also known for its various museums. Puppetry and marionette exhibitions are very popular, with a number of puppet festivals throughout the country.[132] Aquapalace Praha in Čestlice near Prague, is the biggest water park in central Europe.[133]

The Czech Republic has a number of beer festivals, including: Czech Beer Festival (the biggest Czech beer festival, it is usually 17 days long and held every year in May in Prague), Pilsner Fest (every year in August in Plzeň), The Olomoucký pivní festival (in Olomouc) or festival Slavnosti piva v Českých Budějovicích (in České Budějovice).

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1857 | 7,016,531 | — |

| 1869 | 7,617,230 | +8.6% |

| 1880 | 8,222,013 | +7.9% |

| 1890 | 8,665,421 | +5.4% |

| 1900 | 9,372,214 | +8.2% |

| 1910 | 10,078,637 | +7.5% |

| 1921 | 10,009,587 | −0.7% |

| 1930 | 10,674,386 | +6.6% |

| 1950 | 8,896,133 | −16.7% |

| 1961 | 9,571,531 | +7.6% |

| 1970 | 9,807,697 | +2.5% |

| 1980 | 10,291,927 | +4.9% |

| 1991 | 10,302,215 | +0.1% |

| 2001 | 10,230,060 | −0.7% |

| 2011 | 10,436,560 | +2.0% |

| 2016 | 10,572,427 | +1.3% |

The total fertility rate (TFR) in 2015 was estimated at 1.57 children born/woman, which is below the replacement rate of 2.1, and one of the lowest in the world.[134] The Czech Republic subsequently has one of the oldest populations in the world, with an average age of 42.5 years.[135] The life expectancy in 2013 was estimated at 77.56 years (74.29 years male, 81.01 years female).[136] Immigration increased the population by almost 1% in 2007. About 77,000 people immigrate to the Czech Republic annually.[137] Vietnamese immigrants began settling in the Czech Republic during the Communist period, when they were invited as guest workers by the Czechoslovak government.[138] In 2009, there were about 70,000 Vietnamese in the Czech Republic.[139] Most decide to stay in the country permanently.[140]

According to preliminary results of the 2011 census, the majority of the inhabitants of the Czech Republic are Czechs (63.7%), followed by Moravians (4.9%), Slovaks (1.4%), Poles (0.4%), Germans (0.2%) and Silesians (0.1%). As the 'nationality' was an optional item, a substantial number of people left this field blank (26.0%).[141] According to some estimates, there are about 250,000 Romani people in the Czech Republic.[142][143] The Polish minority resides mainly in the Zaolzie region.[144]

There were 496,413 (4.5% of population) foreigners residing in the country in 2016, according to the Czech Statistical Office, with the largest groups being Ukrainian (22%), Slovak (22%), Vietnamese (12%), Russian (7%) and German (4%). Most of the foreign population lives in Prague (37.3%) and Central Bohemia Region (13.2%).[145]

The Jewish population of Bohemia and Moravia, 118,000 according to the 1930 census, was virtually annihilated by the Nazi Germans during the Holocaust.[146] There were approximately 4,000 Jews in the Czech Republic in 2005.[147] The former Czech prime minister, Jan Fischer, is of Jewish faith.[148]

At the turn of the 20th century, Chicago was the city with the third largest Czech population,[149] after Prague and Vienna.[150] At the 2010 US census, there were 1,533,826 Americans of full or partial Czech descent.[151]

Urbanization

Religion

The Czech Republic has one of the least religious populations in the world with 75%[153] to 79%[154] of people not declaring any religion or faith in polls and the percentage of convinced atheists being third highest (30%) only behind China (47%) and Japan (31%).[155] The Czech people have been historically characterized as "tolerant and even indifferent towards religion".[156]

Christianization in the 9th and 10th centuries introduced Catholicism. After the Bohemian Reformation, most Czechs became followers of Jan Hus, Petr Chelčický and other regional Protestant Reformers. Taborites and Utraquists were major Hussite groups. During the Hussite Wars, Utraquists sided with the Catholic Church. Following the joint Utraquist—Catholic victory, Utraquism was accepted as a distinct form of Christianity to be practiced in Bohemia by the Catholic Church while all remaining Hussite groups were prohibited. After the Reformation, some Bohemians went with the teachings of Martin Luther, especially Sudeten Germans. In the wake of the Reformation, Utraquist Hussites took a renewed increasingly anti-Catholic stance, while some of the defeated Hussite factions (notably Taborites) were revived. After the Habsburgs regained control of Bohemia, the whole population was forcibly converted to Catholicism—even the Utraquist Hussites. Going forward, Czechs have become more wary and pessimistic of religion as such. A long history of resistance to the Catholic Church followed. It suffered a schism with the neo-Hussite Czechoslovak Hussite Church in 1920, lost the bulk of its adherents during the Communist era and continues to lose in the modern, ongoing secularization. Protestantism never recovered after the Counter-Reformation was introduced by the Austrian Habsburgs in 1620.

According to the 2011 census, 34% of the population stated they had no religion, 10.3% was Catholic, 0.8% was Protestant (0.5% Czech Brethren and 0.4% Hussite[157]), and 9% followed other forms of religion both denominational or not (of which 863 people answered they are Pagan). 45% of the population did not answer the question about religion.[6] From 1991 to 2001 and further to 2011 the adherence to Catholicism decreased from 39% to 27% and then to 10%; Protestantism similarly declined from 3.7% to 2% and then to 0.8%.[158] The Muslim population is estimated to be 20,000 representing 0.2% of the Czech population.[159]

Education

Education in the Czech Republic is compulsory for 9 years and citizens have access to a tuition-free university education, while the average number of years of education is 13.1.[161] Additionally, the Czech Republic has a relatively equal educational system in comparison with other countries in Europe.[161] Founded in 1348, Charles University was the first university in Central Europe. Other major universities in the country are Masaryk University, Czech Technical University, Palacký University, Academy of Performing Arts and University of Economics.

The Programme for International Student Assessment, coordinated by the OECD, currently ranks the Czech education system as the 15th most successful in the world, higher than the OECD average.[162] The UN Education Index ranks the Czech Republic 10th as of 2013 (positioned behind Denmark and ahead of South Korea).[163]

Health

Healthcare in the Czech Republic is similar in quality to other developed nations. The Czech universal health care system is based on a compulsory insurance model, with fee-for-service care funded by mandatory employment-related insurance plans.[164] According to the 2016 Euro health consumer index, a comparison of healthcare in Europe, the Czech healthcare is 13th, ranked behind Sweden and two positions ahead of the United Kingdom.[165]

Culture

Art

Venus of Dolní Věstonice is the treasure of prehistoric art. Theodoric of Prague was the most famous Czech painter in the Gothic era. For example, he decorated the castle Karlstejn. In the Baroque era, the famous painters were Wenceslaus Hollar, Jan Kupecký, Karel Škréta, Anton Raphael Mengs or Petr Brandl, sculptors Matthias Braun and Ferdinand Brokoff. In the first half of the 19th century, Josef Mánes joined the romantic movement. In the second half of the 19th century had the main say the so-called "National Theatre generation": sculptor Josef Václav Myslbek and painters Mikoláš Aleš, Václav Brožík, Vojtěch Hynais or Julius Mařák. At the end of the century came a wave of Art Nouveau. Alfons Mucha became the main representative. He is today the most famous Czech painter. He is mainly known for Art Nouveau posters and his cycle of 20 large canvases named the Slav Epic, which depicts the history of Czechs and other Slavs.

As of 2012, the Slav Epic can be seen in the Veletržní Palace of the National Gallery in Prague, which manages the largest collection of art in the Czech Republic. Max Švabinský was another important Art nouveau painter. The 20th century brought avant-garde revolution. In the Czech lands mainly expressionist and cubist: Josef Čapek, Emil Filla, Bohumil Kubišta, Jan Zrzavý. Surrealism emerged particularly in the work of Toyen, Josef Šíma and Karel Teige. In the world, however, he pushed mainly František Kupka, a pioneer of abstract painting. As illustrators and cartoonists in the first half of the 20th century gained fame Josef Lada, Zdeněk Burian or Emil Orlík. Art photography has become a new field (František Drtikol, Josef Sudek, later Jan Saudek or Josef Koudelka).

The Czech Republic is known worldwide for its individually made, mouth blown and decorated Bohemian glass.

Architecture

The earliest preserved stone buildings in Bohemia and Moravia date back to the time of the Christianization in the 9th and 10th century. Since the Middle Ages, the Czech lands have been using the same architectural styles as most of Western and Central Europe. The oldest still standing churches were built in the Romanesque style (St. George's Basilica, St. Procopius Basilica in Třebíč). During the 13th century it was replaced by the Gothic style (Charles Bridge, Bethlehem Chapel, Old New Synagogue, Sedlec Ossuary, Old Town Hall with Prague astronomical clock, Church of Our Lady before Týn). In the 14th century Emperor Charles IV invited to his court in Prague talented architects from France and Germany, Matthias of Arras and Peter Parler (Karlštejn, St. Vitus Cathedral, St. Barbara's Church in Kutná Hora). During the Middle Ages, many fortified castles were built by the king and aristocracy, as well as many monasteries (Strahov Monastery, Špilberk, Křivoklát Castle, Vyšší Brod Monastery). During the Hussite wars, many of them were damaged or destroyed.

The Renaissance style penetrated the Bohemian Crown in the late 15th century when the older Gothic style started to be slowly mixed with Renaissance elements (architects Matěj Rejsek, Benedikt Rejt and their Powder Tower). An example of the pure Renaissance architecture in Bohemia is the Queen Anne's Summer Palace, which was situated in a newly established garden of Prague Castle. Evidence of the general reception of the Renaissance in Bohemia, involving a massive influx of Italian architects, can be found in spacious châteaux with arcade courtyards and geometrically arranged gardens (Litomyšl Castle, Hluboká Castle).[166] Emphasis was placed on comfort, and buildings that were built for entertainment purposes also appeared.[167]

In the 17th century, the Baroque style spread throughout the Crown of Bohemia. Very outstanding are the architectural projects of the Czech nobleman and imperial generalissimo Albrecht von Wallenstein from the 1620s (Wallenstein Palace). His architects Andrea Spezza and Giovanni Pieroni reflected the most recent Italian production and were very innovative at the same time. Czech Baroque architecture is considered to be a unique part of the European cultural heritage thanks to its extensiveness and extraordinariness (Kroměříž Castle, Holy Trinity Column in Olomouc, St. Nicholas Church at Malá Strana, Karlova Koruna Chateau). In the first third of the 18th century the Bohemian lands were one of the leading artistic centers of the Baroque style. In Bohemia there was completed the development of the Radical Baroque style created in Italy by Francesco Borromini and Guarino Guarini in a very original way.[168] Leading architects of the Bohemian Baroque were Jean-Baptiste Mathey, František Maxmilián Kaňka, Christoph Dientzenhofer, and his son Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer.

In the 18th century Bohemia produced an architectural peculiarity – the Baroque Gothic style, a synthesis of the Gothic and Baroque styles. This was not a simple return to Gothic details, but rather an original Baroque transformation. The main representative and originator of this style was Jan Blažej Santini-Aichel, who used this style in renovating medieval monastic buildings or in Pilgrimage Church of Saint John of Nepomuk.[166]

During the 19th century, the revival architectural styles were very popular in the Bohemian monarchy. Many churches were restored to their presumed medieval appearance and there were constructed many new buildings in the Neo-Romanesque, Neo-Gothic and Neo-Renaissance styles (National Theatre, Lednice–Valtice Cultural Landscape, Cathedral of St. Peter and Paul in Brno). At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries the new art style appeared in the Czech lands – Art Nouveau. The best-known representatives of Czech Art Nouveau architecture were Osvald Polívka, who designed the Municipal House in Prague, Josef Fanta, the architect of the Prague Main Railway Station, Jan Letzel, Josef Hoffmann and Jan Kotěra.

Bohemia contributed an unusual style to the world's architectural heritage when Czech architects attempted to transpose the Cubism of painting and sculpture into architecture (House of the Black Madonna). During the first years of the independent Czechoslovakia (after 1918), a specifically Czech architectural style, called Rondo-Cubism, came into existence. Together with the pre-war Czech Cubist architecture it is unparalleled elsewhere in the world. The first Czechoslovak president T. G. Masaryk invited the prominent Slovene architect Jože Plečnik to Prague, where he modernized the Castle and built some other buildings (Church of the Most Sacred Heart of Our Lord).

Between World Wars I and II, Functionalism, with its sober, progressive forms, took over as the main architectural style in the newly established Czechoslovak Republic. In the city of Brno, one of the most impressive functionalist works has been preserved – Villa Tugendhat, designed by the architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.[166] The most significant Czech architects of this era were Adolf Loos, Pavel Janák and Josef Gočár.

After World War II and the Communist coup in 1948, art in Czechoslovakia became strongly Soviet influenced. Hotel International in Prague is a brilliant example of the so-called Socialist realism, the Stalinistic art style of the 1950s. The Czechoslovak avant-garde artistic movement known as the Brussels style (named after the Brussels World's Fair Expo 58) became popular in the time of political liberalization of Czechoslovakia in the 1960s. Brutalism dominated in the 1970s and 1980s (Kotva Department Store, Ostravar Aréna, Barrandov Bridge, Transgas building).

Even today, the Czech Republic is not shying away from the most modern trends of international architecture. This fact is attested to by a number of projects by world-renowned architects (Frank Gehry and his Dancing House, Jean Nouvel, Ricardo Bofill, and John Pawson). There are also contemporary Czech architects whose works can be found all over the world (Vlado Milunić, Eva Jiřičná, Jan Kaplický).[166]

Literature

In a strict sense, Czech literature is the literature written in the Czech language. A more liberal definition incorporates all literary works written in the Czech lands regardless of language. The literature from the area of today's Czech Republic was mostly written in Czech, but also in Latin and German or even Old Church Slavonic. Thus Franz Kafka, who—while bilingual in Czech and German[169][170]—wrote his works (The Trial, The Castle) in German, during the era of Austrian rule, can represent the Czech, German or Austrian literature depending on the point of view.

Influential Czech authors who wrote in Latin include Cosmas of Prague († 1125), Martin of Opava († 1278), Peter of Zittau († 1339), John Hus († 1415), Bohuslav Hasištejnský z Lobkovic (1461–1510), Jan Dubravius (1486–1553), Tadeáš Hájek (1525–1600), Johannes Vodnianus Campanus (1572–1622), John Amos Comenius (1592–1670), and Bohuslav Balbín (1621–1688).

In the second half of the 13th century, the royal court in Prague became one of the centers of the German Minnesang and courtly literature (Reinmar von Zweter, Heinrich von Freiberg, Ulrich von Etzenbach, Wenceslaus II of Bohemia). The most famous Czech medieval German-language work is the Ploughman of Bohemia (Der Ackermann aus Böhmen), written around 1401 by Johannes von Tepl. The heyday of Czech German-language literature can be seen in the first half of the 20th century, which is represented by the well-known names of Franz Kafka, Max Brod, Franz Werfel, Rainer Maria Rilke, Karl Kraus, Egon Erwin Kisch, and others.

Bible translations played an important role in the development of Czech literature and the standard Czech language. The oldest Czech translation of the Psalms originated in the late 13th century and the first complete Czech translation of the Bible was finished around 1360. The first complete printed Czech Bible was published in 1488 (Prague Bible). The first complete Czech Bible translation from the original languages was published between 1579 and 1593 and is known as the Bible of Kralice. The Codex Gigas from the 12th century is the largest extant medieval manuscript in the world.

Czech-language literature can be divided into several periods: the Middle Ages (Chronicle of Dalimil); the Hussite period (Tomáš Štítný ze Štítného, Jan Hus, Petr Chelčický); the Renaissance humanism (Henry the Younger of Poděbrady, Luke of Prague, Wenceslaus Hajek, Jan Blahoslav, Daniel Adam z Veleslavína); the Baroque period (John Amos Comenius, Adam Václav Michna z Otradovic, Bedřich Bridel, Jan František Beckovský); the Enlightenment and Czech reawakening in the first half of the 19th century (Václav Matěj Kramerius, Karel Hynek Mácha, Karel Jaromír Erben, Karel Havlíček Borovský, Božena Němcová, Ján Kollár, Josef Kajetán Tyl), modern literature in second half of the 19th century (Jan Neruda, Alois Jirásek, Viktor Dyk, Jaroslav Vrchlický, Julius Zeyer, Svatopluk Čech); the avant-garde of the interwar period (Karel Čapek, Jaroslav Hašek, Vítězslav Nezval, Jaroslav Seifert, Jiří Wolker, Vladimír Holan); the years under Communism and the Prague Spring (Josef Škvorecký, Bohumil Hrabal, Milan Kundera, Arnošt Lustig, Václav Havel, Pavel Kohout, Ivan Klíma); and the literature of the post-Communist Czech Republic (Ivan Martin Jirous, Michal Viewegh, Jáchym Topol, Patrik Ouředník, Kateřina Tučková).

Noted journalists include Julius Fučík, Milena Jesenská, and Ferdinand Peroutka.

Jaroslav Seifert was the only Czech writer awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. The famous antiwar comedy novel The Good Soldier Švejk by Jaroslav Hašek is the most translated Czech book in history. It was adapted by Karel Steklý in two color films The Good Soldier Schweik in 1956 and 1957. Widely translated Czech books are also Milan Kundera's The Unbearable Lightness of Being and Karel Čapek's War with the Newts.

The international literary award the Franz Kafka Prize is awarded in the Czech Republic.[171]

The Czech Republic has the densest network of libraries in Europe.[172] At its center stands the National Library of the Czech Republic, based in the baroque complex Klementinum.

Czech literature and culture played a major role on at least two occasions when Czechs lived under oppression and political activity was suppressed. On both of these occasions, in the early 19th century and then again in the 1960s, the Czechs used their cultural and literary effort to strive for political freedom, establishing a confident, politically aware nation.[173]

Music