Zdeněk Burian

Zdeněk Michael František Burian (February 11, 1905 in Kopřivnice, Moravia, Austria-Hungary – July 1, 1981 in Prague, Czechoslovakia) was a Czech painter, book illustrator and palaeoartist whose work played a central role in the development of palaeontological reconstruction. Originally recognised only in his native Czechoslovakia, Burian's fame later spread to an international audience during a remarkable career spanning six decades (1930s to 1980s). He is regarded by many as one of the most influential palaeoartists of the modern era, and a number of subsequent artists have attempted to emulate his style.

Zdeněk Michael František Burian | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 11, 1905 |

| Died | July 1, 1981 (aged 76) |

| Nationality | Czech |

| Occupation | Painter, illustrator |

Introduction

Burian was an extremely prolific artist whose works are estimated to number fifteen thousand paintings and drawings (ink pen and pencil).[1] He illustrated many books (including natural history subjects and numerous classic novels such as Robinson Crusoe, Tarzan of the Apes, Plutonia) and book covers, but it is within the fields of palaeontology and palaeoanthropology that Burian's influence has been most notable. Since the late 1950s and early 1960s when Burian's work became known in the west through a series of large-format books released by the Artia publishing house, numerous scholarly and popular books on prehistoric life have featured his work, either as originals or as art based closely on them.

Early career and influence on palaeontology

Burian's first experience with prehistoric illustration was in the early 1930s, working on the fictional books set in various prehistoric times written by Eduard Štorch, an amateur archaeologist. These illustrations brought him to university palaeontologist Josef Augusta's attention. Burian worked in cooperation with Augusta from 1935 until Augusta's death in 1968.[2] Subsequently, he worked with Zdeněk Špinar. He painted accurate and magnificent reconstructions representing all forms of prehistoric life from many parts of the globe, from the earliest invertebrates to a vast array of fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals and birds, as well as panoramic vistas of the landscapes in which they lived. Close to 500 prehistoric images were painted by him between the early 1930s and 1981.

Whilst some of Burian's earliest palaeo works depicting North American species were inspired by the pioneering American palaeo-artist Charles R. Knight (see for example, his first renditions of Stegosaurus and Brontotherium), partly because Burian lacked access to skeletal material for such reconstructions, Burian's work was less stylised and more convincing with respect to both the subjects and their landscapes, and soon became highly regarded amongst palaeontologists, especially in Europe. Previous palaeo-artists had often produced speculative works reflecting 19th-century views of large dinosaurs as lethargic reptiles akin to giant lizards with sprawling limbs, but Burian convincingly painted them as active animals with parasagittal (mammal or bird-like) limb-movement and musculature.

Burian depicted the American sauropods Brontosaurus (1940), Diplodocus (1952 & 1965?), and Barosaurus walking on land in elephantine fashion, and his 1941 reconstruction of the East African sauropod Brachiosaurus (the only image showing the main subject in water) became one of the most reproduced dinosaur images in history. Although it is now considered unlikely that Brachiosaurus could have inhaled in deep water (unless it had a strengthened pleural cavity as do some whales), the reconstruction is remarkably realistic and was still being reproduced 60 years after it was painted.

As with many of his works, Burian's sauropod reconstructions reached iconic status, with the celebrated palaeontologist William Elgin Swinton (1900–1994) noting: "The ideas as well as the pictorially beautiful restorations of Zdenek Burian, done under the direction of the late Joseph Augusta (1962), create a lasting impression that appears to be decisive. The Czechoslovakian experts have placed us all in their debt and the life-restorations of Brontosaurus, Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus provide debating points as well as aesthetic satisfaction" (The Dinosaurs, 1970: 189).

Another famous Burian painting (dated 1938) shows the dynamism of his work with a Tyrannosaurus rex rushing to attack one of a pair of startled duck-billed Trachodon as fleet-footed ornithomimids bound off in the distance. Following subsequent palaeontological evidence, the predator was later modified by adding skull protuberances and a stiffer tail. This painting is one of his few works that show dinosaurs in direct conflict.

Many of Burian's early paintings appeared in a series of large format books with text by Augusta, the first of which, Prehistoric Animals, was originally published in Czechoslovakia by Artia (1956) and later in many other countries including Italy, France, Germany, England and Japan. The late S.J. Gould, who was an enthusiast of the work of Charles R. Knight, described it as one of the 20th Century's three most influential visual books on prehistory (many would argue that it was the most influential), and it was followed by a series of other landmark titles: Prehistoric Birds & Reptiles, Prehistoric Sea Monsters, The Book of Mammoths, and Prehistoric Man, all of which became famous and collectable in their own right. The influence of Burian's work is clearly discernible in many later films depicting dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals, right up to the Jurassic Park series.

Artistic style

Although Burian's reconstructions of extinct life are very convincing, his often-reproduced dinosaur reconstructions were all the more remarkable in that he did not have access to skeletal material, but rather depended largely on drawings and photographs provided by his collaborators Augusta and Špinar (although Czechoslovakia had a notable history of palaeontological research, it lacked dinosaur fossils). In many cases, he undertook anatomical reconstructions of his subjects before depicting life restorations, and sometimes painted more than one version of an animal (particularly if the first version had been painted in black and white), examples being Dimetrodon, Tylosaurus, Brachiosaurus, Diplodocus, Stegosaurus, Brontotherium, Arsinoitherium, Phororhacos, Archaeopteryx amongst others.

Many of Burian's early works were accompanied by text from Augusta (often in an almost story-book fashion) and it is within this context and time frame (1940s to 1968) that Burian produced his most memorable and famous works which were used as educational aids in schools across Czechoslovakia to show the succession of life on Earth. His style reflected a classic, almost romantic imagery that rarely showed animals fighting or preying on each other (although some paintings did show carnivores with their prey, they were generally depicted either before the confrontation or after the prey had been dispatched). Two years after Augusta's death, Burian painted what is regarded as his last classic image, the famous 'heroic' Tarbosaurus bataar of Mongolia (an image that was also widely reproduced and copied).

Following Augusta's death, conditions were increasingly placed on Burian's artistic licence and the scientific detail of what he painted, whilst he was also being asked to depict different species within the same scenes but as individual, non-interacting animals as in a montage. Given his background as a novel/action-scene illustrator, and the close collaboration with Augusta the 'story-teller', Burian viewed the subjects of his paintings as very real animals (as would a natural history artist), and the new restrictions did not sit well with him. An example of how his work was compromised is evident in another version of Brachiosaurus that he painted in his later years under the direction of Vratislav Mazak; the animal, now shown on dry land, appears oddly out of proportion and fails to compare to the celebrated 1941 version. In his later years, Burian was in demand by publishers requesting bland, catalogue-like stand-alone prehistoric animal images as illustrations for reference books, a style that Burian neither favoured nor excelled at.

Burian's works, which vary in size from A4 to several square metres, were mostly executed in oils, both in colour and black and white, and exhibit keen attention to detail and unmistakable realism whilst maintaining a strong sense of atmosphere. Whilst his style was very traditional, it was combined with a dynamism that represented a break with the often staid palaeo-reconstructions of previous artists. A feature of many of the paintings, and one that is missing from the work of other palaeo artists, is the realistic effect of movement and action which was achieved not only by the dynamic positions of the subjects, but by a clever blurring of the edges of moving objects (such as the tips of waves or palm fronds in the wind) to produce a clever effect of photo-realism. It has often been noted that Burian's renditions appear to have been painted from life, so close is the perceived association between the subject and its environment. This is perhaps not surprising given that Burian was already well accomplished at painting natural history subjects before he began painting prehistoric scenes.

Legacy

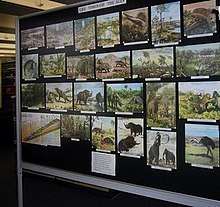

Many Burian paintings have become celebrated images of palaeontology and palaeoanthropology, especially the frequently reproduced images of Mesozoic reptiles (pterosaurs, dinosaurs, mosasaurs and plesiosaurs) whilst his evocative depictions of proboscideans, Ice Age mammals, and a remarkable series of paintings of early hominids through to modern man are without equal. He also painted extant native peoples of the world, including those of Africa, South America and the South Pacific. Original Burian paintings are on exhibit at Dvůr Králové Zoo (especially his large oil canvas), at the National Museum (Prague) and at the Anthropos Museum in Brno (particularly his anthropological reconstructions).

Initially released by Czech publishers followed by western publishers Paul Hamlyn and Thames & Hudson with translated texts, Burian's work was later widely reproduced (often as teaching material) by European and American authors (including Edwin Colbert). Images based on his paintings have featured on postage stamps issued by many countries, and the pioneering director/animator Karel Zeman used Burian paintings as guides to produce 2-D and 3-D animated models for his 1955 landmark feature film Cesta do pravěku (released in altered format in the US as Journey to the Beginning of Time). The 1985 Soviet mini-series Guest from the Future employed Burian's artwork in a scene where robot Werther compares young boy Kolya to various life forms in order to ascertain his identity.

Burian's work has probably inspired more imitators in the field of palaeo-reconstruction than any other artist, and his prehistoric paintings have frequently been copied, and not always with acknowledgement. A notable case is A New Look at the Dinosaurs, by Alan J. Charig (1979), British Museum Natural History, which featured thinly-disguised ink copies of Burian paintings inversed as mirror images. Numerous other examples include many Adèle Blanc-sec comic strips which depict dinosaurs closely resembling Burian's work (e.g. the Tarbosaurus [tome 2] and the pterodactyl of 'Adèle and the Beast'), the 1992 video game Ecco the Dolphin which features in-game artwork inspired by Burian and recreated in pixels by Zsolt Balogh, and the hunting game series Carnivores containing creatures influenced by Burian's art.

In 2015, Google Doodle commemorated his 110th birthday.[3]

In 2017, the first valid Czech dinosaur was named Burianosaurus augustai, honouring both Burian and Josef Augusta.[4]

Partial bibliography

- Life before Man Zdeněk V. Špinar, illustrated by Burian. Prague: Artia, 1972. Reprinted by Crescent Books, 1981. ISBN 0-517-34722-9

References

- Lescaze, Zoë (2017). Paleoart: Visions of the prehistoric past. Taschen. pp. 164–193. ISBN 978-3836555111.

- Hochmanová-Burianová, Eva (1991). Zdeněk Burian - pravěk a dobrodružství (rodinné vzpomínky). Prague: Magnet-Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 80-85434-28-8.

- Zdeněk Burian’s 110th Birthday

- Madzia, Daniel; Boyd, Clint A.; Mazuch, Martin (2017). "A basal ornithopod dinosaur from the Cenomanian of the Czech Republic". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 16 (11): 967–979. doi:10.1080/14772019.2017.1371258.

External links

- Gallery of 31 paintings with descriptions (in Russian)

- Gallery of 152 paintings (in Russian)

- Gallery of 60 paintings (in Russian)

- Zdenek Burian Museum (Czech)

- Zdenek Burian memorabilia

- Zdenek Burian - Illustrations

- Zdeněk Burian - Upper Paleolithic large color images

- Zdeněk Burian - Middle Paleolithic large color images