Bedřich Smetana

Bedřich Smetana (/ˌbɛdərʒɪx ˈsmɛtənə/ BED-ər-zhikh SMET-ə-nə,[1][2][3] Czech: [ˈbɛdr̝ɪx ˈsmɛtana] (![]()

Smetana was naturally gifted as a composer, and gave his first public performance at the age of 6. After conventional schooling, he studied music under Josef Proksch in Prague. His first nationalistic music was written during the 1848 Prague uprising, in which he briefly participated. After failing to establish his career in Prague, he left for Sweden, where he set up as a teacher and choirmaster in Gothenburg, and began to write large-scale orchestral works.

In the early 1860s, a more liberal political climate in Bohemia encouraged Smetana to return permanently to Prague. He threw himself into the musical life of the city, primarily as a champion of the new genre of Czech opera. In 1866 his first two operas, The Brandenburgers in Bohemia and The Bartered Bride, were premiered at Prague's new Provisional Theatre, the latter achieving great popularity. In that same year, Smetana became the theatre's principal conductor, but the years of his conductorship were marked by controversy. Factions within the city's musical establishment considered his identification with the progressive ideas of Franz Liszt and Richard Wagner inimical to the development of a distinctively Czech opera style. This opposition interfered with his creative work, and might have hastened a decline in health that precipitated his resignation from the theatre in 1874.

By the end of 1874, Smetana had become completely deaf but, freed from his theatre duties and the related controversies, he began a period of sustained composition that continued for almost the rest of his life. His contributions to Czech music were increasingly recognised and honoured, but a mental collapse early in 1884 led to his incarceration in an asylum and subsequent death. Smetana's reputation as the founding father of Czech music has endured in his native country, where advocates have raised his status above that of his contemporaries and successors. However, relatively few of Smetana's works are in the international repertory, and most foreign commentators tend to regard Antonín Dvořák as a more significant Czech composer.

Biography

Family background and childhood

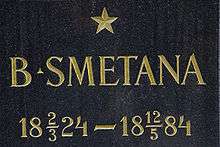

Bedřich Smetana, first named Friedrich Smetana, was born on 2 March 1824, in Litomyšl (German: Leitomischl), east of Prague near the traditional border between Bohemia and Moravia, then provinces of the Habsburg Empire. He was the third child, and first son, of František Smetana and his third wife Barbora Lynková. František had fathered eight children in two earlier marriages, five daughters surviving infancy; he and Barbora had ten more children, of whom seven reached adulthood.[4][5] At this time, under Habsburg rule, German was the official language of Bohemia. František knew Czech but, for business and social reasons, rarely used it; and his children were ignorant of correct Czech until much later in their lives.[6]

The Smetana family came from the Hradec Králové (German: Königgrätz) region of Bohemia. František had initially learned the trade of a brewer, and had acquired moderate wealth during the Napoleonic Wars by supplying clothing and provisions to the French Army. He subsequently managed several breweries before coming to Litomyšl in 1823 as brewer to Count Waldstein, whose Renaissance castle dominates the town.[4][7]

František Smetana played violin in a string quartet, and Barbora Smetana was a dancer.[8] Bedřich was introduced to music by his father and in October 1830, at the age of six, gave his first public performance. At a concert held in Litomyšl's Philosophical Academy he played a piano arrangement of Auber's overture to La muette de Portici, to a rapturous reception.[9][10] In 1831 the family moved to Jindřichův Hradec in the south of Bohemia—the region where, a generation later, Gustav Mahler grew up.[7][11] Here, Smetana attended the local elementary school and later the gymnasium. He also studied violin and piano, discovering the works of Mozart and Beethoven, and began composing simple pieces, of which one, a dance (Kvapiček, or "Little Galop"), survives in sketch form.[11][12]

In 1835, František retired to a farm in the south-eastern region of Bohemia.[12] There being no suitable local school, Smetana was sent to the gymnasium at Jihlava, where he was homesick and unable to study. He then transferred to the Premonstratensian school at Německý Brod, where he was happier and made good progress.[12] Among the friends he made here was the future Czech revolutionary poet Karel Havlíček,[13] whose departure for Prague in 1838 may have influenced Smetana's own desire to experience life in the capital. The following year, with František's approval, he enrolled at Prague's Academic Grammar School under Josef Jungmann, a distinguished poet and linguist who was a leading figure in the movement for Czech national revival.[14]

Apprentice musician

First steps

Smetana arrived in Prague in the autumn of 1839. Finding Jungmann's school uncongenial (he was mocked by his classmates for his country manners),[14] he soon began missing classes. He attended concerts, visited the opera, listened to military bands and joined an amateur string quartet for whom he composed simple pieces.[14] After Liszt gave a series of piano recitals in the city, Smetana became convinced that he would find satisfaction only in a musical career.[14] He confided to his journal that he wanted "to become a Mozart in composition and a Liszt in technique".[15][16] However, the Prague idyll ended when František discovered his son's truancy, and removed him from the city.[14] František at this time saw music as a diverting pastime, not as a career choice.[6] Smetana was placed temporarily with his uncle in Nové Město, where he enjoyed a brief romance with his cousin Louisa. He commemorated their passion in Louisa's Polka, Smetana's earliest complete composition that has survived.[17]

An older cousin, Josef Smetana, a teacher at the Premonstratensian School in Plzeň (German: Pilsen), then offered to supervise the boy's remaining schooling, and in the summer of 1840 Smetana departed for Plzeň.[8] He remained there until he completed his schooling in 1843. His skills as a pianist were in great demand at the town's many soirées, and he enjoyed a hectic social life.[16] This included a number of romances, the most important of which was with Kateřina Kolářová, whom he had known briefly in his early childhood. Smetana was entirely captivated with her, writing in his journal: "When I am not with her I am sitting on hot coals and have no peace".[18] He composed several pieces for her, among which are two Quadrilles, a song duet, and an incomplete piano study for the left hand.[19] He also composed his first orchestral piece, a B-flat minuet.[20]

Student and teacher

By the time Smetana completed his schooling, his father's fortunes had declined. Although František now agreed that his son should follow a musical career, he could not provide financial support.[16][19] In August 1843 Smetana departed for Prague with twenty gulden,[21][22] and no immediate prospects.[23] Kateřina Kolářová's mother introduced Smetana to Josef Proksch, then head of the Prague Music Institute (where Kateřina was studying), with whom he began composition lessons. [8][19] In January 1844 Proksch agreed to take Smetana as a pupil, and at the same time the young musician's financial difficulties were eased when he secured an appointment as music teacher to the family of a nobleman, Count Thun.[8] During the course of his studies, Proksch introduced Smetana to both Liszt and Berlioz.[8]

For the next three years, besides teaching piano to the Thun children, Smetana studied theory and composition under Proksch. The works he composed in these years include songs, dances, bagatelles, impromptus and the G minor Piano Sonata.[24] In 1846 Smetana attended concerts given in Prague by Berlioz, and in all likelihood met the French composer at a reception arranged by Proksch.[25] At the home of Count Thun he met Robert and Clara Schumann, and showed them his G minor sonata, but failed to win their approval for this work—they detected too much of Berlioz in it.[8] Meanwhile, his friendship with Kateřina blossomed. In June 1847, on resigning his position in the Thun household, Smetana recommended her as his replacement. He then set out on a tour of Western Bohemia, hoping to establish a reputation as a concert pianist.[26]

Early career

Revolutionary

Smetana's concert tour to Western Bohemia was poorly supported, so he abandoned it and returned to Prague, where he made a living from private pupils and occasional appearances as an accompanist in chamber concerts.[25] He also began work on his first major orchestral work, the Overture in D major.[27]

For a brief period in 1848, Smetana was a revolutionary. In the climate of political change and upheaval that swept through Europe in that year, a pro-democracy movement in Prague led by Smetana's old friend Karel Havlíček was urging an end to Habsburg absolutist rule and for more political autonomy.[28] A Citizens' Army ("Svornost") was formed to defend the city against possible attack. Smetana wrote a series of patriotic works, including two marches dedicated respectively to the Czech National Guard and the Students' Legion of the University of Prague, and The Song of Freedom to words by Ján Kollár.[29] In June 1848, as the Habsburg armies moved to suppress rebellious tendencies, Prague came under attack from the Austrian forces led by the Prince of Windisch-Grätz. As a member of Svornost, Smetana helped to man the barricades on the Charles Bridge.[28] The nascent uprising was quickly crushed, but Smetana avoided the imprisonment or exile received by leaders such as Havlíček.[28] During his brief spell with Svornost, he met the writer and leading radical, Karel Sabina, who would later provide libretti for Smetana's first two operas.[28]

Piano Institute

Early in 1848, Smetana wrote to Franz Liszt, whom he had not yet met, asking him to accept the dedication of a new piano work, Six Characteristic Pieces, and recommend it to a publisher. He also requested a loan of 400 gulden, to enable him to open a music school. Liszt replied cordially, accepting the dedication and promising to help find a publisher, but he offered no financial assistance.[30][31] This encouragement was the beginning of a friendship that was of great value to Smetana in his subsequent career.[32] Despite Liszt's lack of financial support, Smetana was able to start a Piano Institute in late August 1848, with twelve students.[33] After a period of struggle the Institute began to flourish and became briefly fashionable, particularly among supporters of Czech nationalism in whose eyes Smetana was developing a reputation. Proksch wrote of Smetana's support for his people's cause, and said that he "could well become the transformer of my ideas in the Czech language."[34] In 1849 the Institute was relocated to the home of Kateřina's parents, and began to attract distinguished visitors; Liszt came regularly, and the former Austrian emperor Ferdinand, who had settled in Prague, attended the school's matinée concerts.[34] Smetana's performances in these concerts became a recognised feature of Prague's musical life. In this time of relative financial stability Smetana married his beloved, the young pianist Kateřina Kolářová, on 27 August 1849. Four daughters were born to the couple between 1851 and 1855.[31]

Budding composer

In 1850, notwithstanding his revolutionary sentiments, Smetana accepted the post of Court Pianist in Ferdinand's establishment in Prague Castle.[29][34] He continued teaching in the Piano Institute, and devoted himself increasingly to composition. His works, mainly for the piano, included the three-part Wedding Scenes, some of the music of which was later used in The Bartered Bride.[35] He also wrote numerous short experimental pieces collected under the name Album Leaves, and a series of polkas.[35] During 1853–54 he worked on a major orchestral piece, the Triumphal Symphony, composed to commemorate the wedding of Emperor Franz Joseph.[31] The symphony was rejected by the Imperial Court, possibly on the grounds that the brief musical references to the Austrian national anthem were not sufficiently prominent. Undeterred, Smetana hired an orchestra at his own expense to perform the symphony at the Konvikt Hall in Prague on 26 February 1855. The work was coolly received, and the concert was a financial failure.[36]

Private sorrows and professional disenchantment

In the years between 1854 and 1856 Smetana suffered a series of personal blows. In July 1854 his second daughter, Gabriela, died of tuberculosis. A year later his eldest daughter Bedřiška, who at the age of four was showing signs of musical precocity, died of scarlet fever.[37] Smetana wrote his Piano Trio in G minor as a tribute to her memory; it was performed in Prague on 3 December 1855 and, according to the composer, was received "harshly" by the critics, although Liszt praised it.[38] Smetana's sorrows continued; just after Bedřiška's death a fourth daughter, Kateřina, had been born but she, too, died in June 1856. By this time Smetana's wife Kateřina had also been diagnosed with tuberculosis.[37]

In July 1856, Smetana received news of the death in exile of his revolutionary friend Karel Havlíček.[39] The political climate in Prague was a further source of gloom; hopes of a more enlightened government and social reform following Franz Joseph's accession in 1848 had faded as Austrian absolutism reasserted itself under Baron Alexander von Bach.[39] Despite the good name of the Piano Institute, Smetana's status as a concert pianist was generally considered below that of contemporaries such as Alexander Dreyschock.[39] Critics acknowledged Smetana's "delicate, crystalline touch", closer in style to Chopin than Liszt, but believed that his physical frailty was a serious drawback to his concert-playing ambitions.[35] His main performance success during this period was his playing of Mozart's D minor Piano Concerto at a concert celebrating the centenary of Mozart's birth, in January 1856.[39] His disenchantment with Prague was growing and, perhaps influenced by Dreyschock's accounts of opportunities in Sweden, Smetana decided to seek success there. On 11 October 1856, after writing to his parents that "Prague did not wish to acknowledge me, so I left it", he departed for Gothenburg.[40]

Years of travel

Gothenburg

Smetana initially went to Gothenburg without Kateřina. Writing to Liszt, he said that the people there were musically unsophisticated, but he saw this as an opportunity "...for an impact I could never have achieved in Prague."[40] Within a few weeks of his arrival, he had given his first recital, opened a music school that was rapidly overwhelmed by applications,[41] and become conductor of the Gothenburg Society for Classical Choral Music.[41] In a few months Smetana had achieved both professional and social recognition in the city, although he found little time for composition; two intended orchestral works, provisionally entitled Frithjof and The Viking's Voyage, were sketched but abandoned.[42]

In summer 1857, Smetana came home to Prague and found Kateřina in failing health. In June, Smetana's father František died.[43] That autumn Smetana returned to Gothenburg, with Kateřina and their surviving daughter Žofie, but before doing so he visited Liszt in Weimar. The occasion was the Karl August Goethe-Schiller Jubilee celebrations; Smetana attended performances of Liszt's Faust Symphony and the symphonic poem Die Ideale, which invigorated and inspired him.[44] Liszt was Smetana's principal teacher throughout the latter's creative life, and at this time was crucially able to revive his spirits and rescue him from the relative artistic isolation of Gothenburg.[40]

Back in Sweden, Smetana found among his new pupils a young housewife, Fröjda Benecke, who briefly became his muse and his mistress. In her honour Smetana transcribed two songs from Schubert's Die schöne Müllerin cycle, and transformed one of his own early piano pieces into a polka entitled Vision at the Ball.[45] He also began composing on a more expansive scale. In 1858 he completed the symphonic poem Richard III, his first major orchestral composition since the Triumphal Symphony. He followed this with Wallenstein's Camp, inspired by Friedrich Schiller's Wallenstein drama trilogy,[46] and began a third symphonic poem Hakon Jarl, based on the tragic drama by Danish poet Adam Oehlenschläger.[47] Smetana also wrote two large-scale piano works: Macbeth and the Witches, and an Étude in C in the style of Liszt.[48]

Bereavement, remarriage and return to Prague

Kateřina's health gradually worsened and in the spring of 1859 failed completely. Homeward bound, she died at Dresden on 19 April 1859. Smetana wrote that she had died "gently, without our knowing anything until the quiet drew my attention to her."[49] After placing Žofie with Kateřina's mother, Smetana spent time with Liszt in Weimar, where he was introduced to the music of the comic opera Der Barbier von Bagdad, by Liszt's pupil Peter Cornelius.[50] This work would influence Smetana's own later career as an opera composer.[51] Later that year he stayed with his younger brother Karel, and fell in love with Karel's sister-in-law Barbora (Bettina) Ferdinandiová, sixteen years his junior. He proposed marriage, and having secured her promise returned to Gothenburg for the 1859–60 winter.[40] The marriage took place the following year, on 10 July 1860, after which Smetana and his new wife returned to Sweden for a final season. This culminated in April 1861 with a piano performance in Stockholm, attended by the Swedish royal family. The couple's first daughter, Zdeňka, was born in September 1861.[47]

Meanwhile, the defeat of Franz Joseph's army at Solferino in 1859 had weakened the Habsburg Empire, and led to the fall from power of von Bach.[52] This had gradually brought a more enlightened atmosphere to Prague, and by 1861 Smetana was seeing prospects of a better future for Czech nationalism and culture.[15][47] Before deciding his own future, in September Smetana set out on a concert tour of the Netherlands and Germany. He was still hoping to secure a reputation as a pianist, but once again he experienced failure.[47] Back in Prague, he conducted performances of Richard III and Wallenstein's Camp in the Žofín Island concert hall in January 1862, to a muted reception. Critics accused him of adhering too closely to the "New German" school represented primarily by Liszt;[53] Smetana responded that "a prophet is without honour in his own land."[47] In March 1862 he made a last brief visit to Gothenburg, but the city no longer held his interest; it appeared to him a provincial backwater and, whatever the difficulties, he now determined to seek his musical future in Prague: "My home has rooted itself into my heart so much that only there do I find real contentment. It is to this that I will sacrifice myself."[54]

National prominence

Seeking recognition

In 1861, it was announced that a Provisional Theatre would be built in Prague, as a home for Czech opera.[8] Smetana saw this as an opportunity to write and stage opera that would reflect Czech national character, similar to the portrayals of Russian life in Mikhail Glinka's operas.[15] He hoped that he might be considered for the theatre's conductorship, but the post went to Jan Nepomuk Maýr, apparently because the conservative faction in charge of the project considered Smetana a "dangerous modernist", in thrall to avant garde composers such as Liszt and Wagner.[55][56] Smetana then turned his attention to an opera competition, organised by Count Jan von Harrach, which offered prizes of 600 gulden each for the best comic and historical operas based on Czech culture.[55] With no useful model on which to base his work—Czech opera as a genre scarcely existed—Smetana had to create his own style. He engaged Karel Sabina, his comrade from the 1848 barricades, as his librettist,[57] and received Sabina's text in February 1862, a story of the 13th century invasion of Bohemia by Otto of Brandenburg. In April 1863 he submitted the score, under the title of The Brandenburgers in Bohemia.[57][58]

At this stage in his career, Smetana's command of the Czech language was poor. His generation of Czechs was educated in German,[59] and he had difficulty expressing himself in what was supposedly his native tongue.[58] To overcome these linguistic deficiencies he studied Czech grammar, and made a point of writing and speaking in Czech every day. He had become Chorus Master of the nationalistic Hlahol Choral Society soon after his return from Sweden, and as his fluency in the Czech language developed he composed patriotic choruses for the Society; The Three Riders and The Renegade were performed at concerts in early 1863.[60] In March of that year Smetana was elected president of the music section of Umělecká Beseda, a society for Czech artists.[58] By 1864 he was proficient enough in the Czech language to be appointed as music critic to the main Czech language newspaper Národní listy.[61] Meanwhile, Bettina had given birth to another daughter, Božena.[62]

On 23 April 1864, Smetana conducted Berlioz's choral symphony Roméo et Juliette at a concert celebrating the Shakespeare tercentenary, adding to the programme his own March for the Shakespearean Festival.[55][58] That year, Smetana's bid to become Director of the Prague Conservatory failed. He had set high hopes on this appointment: "My friends are trying to persuade me that this post might have been especially created for me," he wrote to a Swedish friend.[63] Again his hopes were thwarted by his association with the perceived radical Liszt, and the appointing committee chose the conservative patriot Josef Krejčí for the post.[64]

Almost three years passed before Smetana was declared the winner of Harrach's opera competition.[55] Before then, on 5 January 1866, The Brandenburgers had been performed to an enthusiastic reception at the Provisional Theatre—over strong opposition from Maýr, who had refused to rehearse or conduct the piece. The idiom was too advanced for Maýr's liking, and the opera was eventually staged under the composer's own direction.[55] "I was called on stage nine times," Smetana wrote, recording that the house was sold out and that the critics were full of praise.[65] Music historian Rosa Newmarch believes that, although The Brandenburgers has not stood the test of time, it contains all the germs of Smetana's operatic art.[66]

Opera maestro

In July 1863, Sabina had delivered the libretto for a second opera, a light comedy entitled The Bartered Bride, which Smetana composed during the next three years. Because of the success of The Brandenburgers, the management of the Provisional Theatre readily agreed to stage the new opera, which was premiered on 30 May 1866 in its original two-act version with spoken dialogue.[58] The opera went through several revisions and restructures before reaching the definitive three-act form that in due course established Smetana's international reputation.[67][68] The opera's first performance was a failure; it was held on one of the hottest evenings of the year, on the eve of the Austro-Prussian War, with Bohemia under imminent threat of invasion by Prussian troops. Unsurprisingly the occasion was poorly attended, and receipts failed to cover costs.[69] When presented at the Provisional Theatre in its final form, in September 1870, it was a tremendous public success.[70]

Back in 1866, as the composer of The Brandenburgers with its overtones of German military aggression, Smetana thought he might be targeted by the invading Prussians, so he absented himself from Prague until hostilities ceased.[69] He returned in September, and almost immediately achieved a long-standing ambition—appointment as principal conductor of the Provisional Theatre, at an annual salary of 1,200 gulden.[71] In the absence of a body of suitable Czech opera, Smetana in his first season presented standard works by Weber, Mozart, Donizetti, Rossini and Glinka, with a revival of his own Bartered Bride.[67][71] The quality of Smetana's production of Glinka's A Life for the Tsar angered Glinka's champion Mily Balakirev, who expressed himself forcefully. This caused prolonged hostility between the two men.[71][72] On 28 February 1868 Smetana conducted another national opera by another Slavic composer, Halka by Stanisław Moniuszko. On 16 May 1868 Smetana, representing Czech musicians, helped to lay the foundation stone for the future National Theatre;[70] he had written a Festive Overture for the occasion. That same evening Smetana's third opera, Dalibor, was premièred at Prague's New Town Theatre.[58] Although its initial reception was warm its reviews were poor, and Smetana resigned himself to its failure.[73]

Opposition

Early in his Provisional Theatre conductorship Smetana had made a powerful enemy in František Pivoda, the Director of the Prague School of Singing. Formerly a supporter of Smetana, Pivoda was aggrieved when the conductor recruited singing talent from abroad rather than from Pivoda's school.[74][75] In an increasingly bitter public correspondence, Pivoda claimed that Smetana was using his position to further his own career, at the expense of other composers.[76]

Pivoda then took issue with Dalibor, calling it an example of extreme "Wagnerism" and thus, unsuited as a model for Czech national opera.[77] "Wagnerism" meant the adoption of Wagner's theories of a continuous role for the orchestra and the building of an integrated musical drama, rather than a stringing together of lyrical numbers.[58][78] The Provisional Theatre's chairman, František Rieger, had first accused Smetana of Wagnerist tendencies after the first performance of The Brandenburgers,[65] and the issue eventually divided Prague's musical society. The music critic Otakar Hostinský believed that Wagner's theories should be the basis of the national opera, and argued that Dalibor was the beginning of the "correct" direction. The opposite camp, led by Pivoda, supported the principles of Italian opera, in which the voice rather than the orchestra was the predominant dramatic device.[58]

Even within the theatre itself there was division. Rieger led a campaign to eject Smetana from the conductorship and reappoint Maýr, and in December 1872 a petition signed by 86 subscribers to the theatre called for Smetana's resignation.[76] Strong support from vice-chairman Antonín Čísek, and an ultimatum from prominent musicians among whom was Antonín Dvořák, ensured Smetana's survival. In January 1873 he was reappointed, with a bigger salary and increased responsibility as Artistic Director.[58][76]

Smetana gradually brought more operas by emergent Czech composers to the theatre, but little of his own work.[76] By 1872 he had completed his monumental fourth opera, Libuše, his most ambitious work to date,[79] but was withholding its premiere for the future opening of the forthcoming National Theatre.[80] The machinations of Pivoda and his supporters distracted Smetana from composition,[76] and he had further vexation when The Bartered Bride was produced in Saint Petersburg, in January 1871. Although the audience was enthusiastic,[76] press reports were hostile, one describing the work as "no better than that of a gifted fourteen-year-old boy."[81] Smetana was deeply offended, and blamed his old adversary, Balakirev, for inciting negative feelings against the opera.[81]

Final decade

Deafness

In the respite following his reappointment, Smetana concentrated on his fifth opera, The Two Widows, composed between June 1873 and January 1874.[82] After its first performance at the Provisional Theatre on 27 March 1874, Smetana's supporters presented him with a decorative baton.[58] But his opponents continued to attack him, comparing his conductorship unfavourably with the Maýr regime and claiming that under Smetana "Czech opera sickens to death at least once annually."[82] By the summer Smetana was ill; a throat infection was followed by a rash and an apparent blockage to the ears. By mid-August, unable to work, he transferred his duties to his deputy, Adolf Čech. A press announcement stated that Smetana had "become ill as a result of nervous strain caused by certain people recently."[82]

In September, Smetana told the theatre he would resign his appointment unless his health improved.[83] He had become totally deaf in his right ear, and in October lost all hearing in his left ear also. After his subsequent resignation the theatre offered him an annual pension of 1,200 gulden for the continued right to perform his operas, an arrangement Smetana reluctantly accepted.[84] Money raised in Prague by former students, and by former lover Fröjda Benecke in Gothenburg, amounted to 1,244 gulden.[85] This allowed Smetana to seek medical treatment abroad, but to no avail.[58] In January 1875 Smetana wrote in his journal: "If my disease is incurable, then I should prefer to be liberated from this life."[86] His spirits were further lowered at this time by a deterioration in his relationship with Bettina, mainly over money matters.[87] "I cannot live under the same roof as a person who hates and persecutes me," Smetana informed her.[88] Although divorce was considered, the couple stayed unhappily together.[89]

Late flowering

In worsening health, Smetana continued to compose. In June 1876 he, Bettina, and their two daughters left Prague for Jabkenice, the home of his eldest daughter Žofie where, in tranquil surroundings, Smetana was able to work undisturbed.[90] Before leaving Prague he had begun a cycle of six symphonic poems, called Má vlast ("My Fatherland"),[91] and had completed the first two, Vyšehrad and Vltava, which had both been performed in Prague during 1875.[92] In Jabkenice Smetana composed four more movements, the complete cycle being first performed on 5 November 1882 under the baton of Adolf Čech.[93] Other major works composed in these years were the E minor String Quartet, From My Life, a series of Czech dances for piano, several choral pieces and three more operas: The Kiss, The Secret and The Devil's Wall, all of which received their first performances between 1876 and 1882.[93]

The long-delayed premiere of Smetana's opera Libuše finally arrived when the National Theatre opened on 11 June 1881. He had not initially been given tickets, but at the last minute was asked into the theatre director's box. The audience received the work enthusiastically, and Smetana was called to the stage repeatedly.[94][95] Shortly after this event the new theatre was destroyed by fire; despite his infirmities, Smetana helped to raise funds for the rebuilding.[93][96] The restored theatre reopened on 18 November 1883, again with Libuše[93]

These years saw Smetana's growing recognition as the principal exponent of Czech national music.[93] This status was celebrated by several events during Smetana's final years. On 4 January 1880, a special concert in Prague marked the 50th anniversary of his first public performance; Smetana attended, and played his Piano Trio in G minor from 1855. In May 1882 The Bartered Bride was given its 100th performance, an unprecedented event in the history of Czech opera. It was so popular that a repeat "100th performance" was staged.[93] A gala concert and banquet was arranged to honour Smetana's 60th birthday in March 1884, but he was too ill to attend.[93]

Illness and death

In 1879, Smetana had written to a friend, the Czech poet Jan Neruda, revealing fears of the onset of madness.[97] By the winter of 1882–83 he was experiencing depression, insomnia, and hallucinations, together with giddiness, cramp and a temporary loss of speech.[97] In 1883 he began writing a new symphonic suite, Prague Carnival, but could get no further than an Introduction and a Polonaise.[98] He started a new opera, Viola, based on the character in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night,[99] but wrote only fragments as his mental state gradually deteriorated.[98] In October 1883 his behaviour at a private reception in Prague disturbed his friends;[98] by the middle of February 1884 he had ceased to be coherent, and was periodically violent.[100] On 23 April his family, unable to nurse him any longer, removed him to the Kateřinky Lunatic Asylum in Prague, where he died on 12 May 1884.[93][100]

The hospital registered the cause of death as senile dementia.[100] However, Smetana's family believed that his physical and mental decline was due to syphilis.[100] An analysis of the autopsy report, published by the German neurologist Dr Ernst Levin in 1972, came to the same conclusion.[101] Tests carried out by Prof. Emanuel Vlček in the late 20th century on samples of muscular tissue from Smetana's exhumed body provided further evidence of the disease. However, this research has been challenged by Czech physician Dr Jiří Ramba, who has argued that Vlček's tests do not provide a basis for a reliable conclusion, citing the age and state of the tissues and highlighting reported symptoms of Smetana's that were incompatible with syphilis.[102]

Smetana's funeral took place on 15 May, at the Týn Church in Prague's Old Town. The subsequent procession to the Vyšehrad Cemetery was led by members of the Hlahol, bearing torches, and was followed by a large crowd.[100] The grave later became a place of pilgrimage for musical visitors to Prague.[103] On the funeral evening, a scheduled performance of The Bartered Bride at the National Theatre was allowed to proceed, the stage draped with black cloth as a mark of respect.[100]

.jpg)

.jpg)

Smetana was survived by Bettina, their daughters Zdeňka and Božena, and by Žofie. None of them played any significant role in Smetana's musical life. Bettina lived until 1908; Žofie, who had married Josef Schwarz in 1874, predeceased her stepmother, dying in 1902.[5] The younger daughters eventually married, living out their lives away from the public eye.[5] A permanent memorial to Smetana's life and work is the Bedřich Smetana Museum in Prague, founded in 1926 within the Charles University's Institute for Musicology.[104] In 1936 the museum moved to the former Waterworks building on the banks of the Vltava, and since 1976 has been part of the Czech Museum of Music.[104]

The asteroid 2047 Smetana was named in his honour.[105]

Music

The basic materials from which Smetana fashioned his art, according to Newmarch, were nationalism, realism and romanticism.[106] A particular feature of all his later music is its descriptive character—all his major compositions outside his operas are written to programmes, and many are specifically autobiographical.[107] Smetana's champions have recognised the major influences on his work as Liszt, Wagner and Berlioz—the "progressives"—while those same advocates have often played down the significance of "traditionalist" composers such as Rossini, Donizetti, Verdi and Meyerbeer.[108]

Piano works

All but a handful of Smetana's compositions before his departure for Gothenburg are piano works.[109] Some of these early pieces have been dismissed by music historian Harold Schonberg as "bombastic virtuoso rhetoric derived from Liszt".[110] Under Proksch, however, Smetana acquired more polish, as revealed in works such as the G minor Sonata of 1846 and the E-flat Polka of the same year. The set of Six Characteristic Pieces of 1848 was dedicated to Liszt, who described it as "the most outstanding, finely felt and finely finished pieces that have recently come to my note."[111] In this period Smetana planned a cycle of so-called "album leaves", short pieces in every major and minor key, after the manner of Chopin's Preludes.[112] The project became somewhat disorganised; in the pieces completed, some keys are repeated while others are unrepresented.[112][113] After Smetana's final return from Gothenburg, when he committed himself primarily to the development of Czech opera, he wrote nothing for the piano for 13 years.[113]

In his last decade Smetana composed three substantial piano cycles. The first, from 1875, was entitled Dreams. It was dedicated to former pupils of Smetana's, who had raised funds to cover medical expenses, and is also a tribute to the composer's models of the 1840s—Schumann, Chopin and Liszt.[113] Smetana's last major piano works were the two Czech Dances cycles of 1877 and 1879. The first of these had the purpose, as Smetana explained to his publisher, of "idealising the polka, as Chopin in his day did with the mazurka."[113] The second cycle is a medley of dances, each given a specific title so that people would know "...which dances with real names we Czechs have."[113]

Vocal and choral

Smetana's early songs are settings of German poems for single voice. Apart from his 1848 Song of Freedom, he did not begin to write pieces for a full choir until after his Gothenburg sojourn, when he composed numerous works for the Hlahol choral society, mostly for unaccompanied male voices.[114] Smetana's choral music is generally nationalistic in character, ranging in scale from the short Ceremonial Chorus written after the death of the composer's revolutionary friend Havlíček, to the setting of Song of the Sea, a substantial work with the character of a choral drama.[115]

Towards the end of his life Smetana returned to simple song-writing, with five Evening Songs (1879) to words by the poet Vítězslav Hálek. His final completed work, Our Song (1883), is the last of four settings of texts by Josef Srb-Debrnov. Despite the state of Smetana's health, this is a happy celebration of Czech song and dance. The piece was lost for many years, and only received its first performance after rediscovery in 1924.[116]

Chamber

Apart from a juvenile fantasia for violin and piano, Smetana composed only four chamber works, yet each had a deep personal significance.[117] The Piano Trio in G minor of 1855 was composed after the death of his daughter Bedřiška; its style is close to that of Robert Schumann, with hints of Liszt, and the overall tone is elegiac.[118] It was 20 years before he returned to the chamber genre with his first String Quartet. This E minor work, subtitled From My Life, was autobiographical in character, illustrating the composer's youthful enthusiasm for his art, his friendships and loves and, in a change of mood, the onset of his deafness represented by a long harmonic E in the final movement above ominous string tremolos.[119] His second String Quartet, in D minor, written in 1882–83 in defiance of his doctor's orders to refrain from all musical activity,[120][121] was composed in short snatches, "a swirl of music of a person who has lost his hearing."[122] It represents Smetana's frustrations with his life, but is not wholly gloomy, and includes a bright polka.[122] It was one of his final compositions; between the two quartets he wrote a violin and piano duet From the homeland, a mixture of melancholy and happiness with strong affinity to Czech folk material.[122]

Orchestral

Dissatisfied with his first large-scale orchestral work, the D major Overture of 1848,[123] Smetana studied passages from Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Weber and Berlioz before producing his Triumphal Symphony of 1853.[124] Though this is dismissed by Rosa Newmarch as "an epithalamium for a Habsburg Prince",[125] Smetana's biographer Brian Large identifies much in the piece that characterises the composer's more mature works.[126] Despite the symphony's rejection by the Court and the lukewarm reception on its premiere, Smetana did not abandon the work. It was well received in Gothenburg in 1860,[127] and a revised version was performed in Prague in 1882, without the "triumphal" tag, under Adolf Čech.[124] The piece is now sometimes called the Festive Symphony.

Smetana's visit to Liszt at Weimar in the summer of 1857, where he heard the latter's Faust Symphony and Die Ideale, caused a material reorientation of Smetana's orchestral music. These works gave Smetana answers to many compositional problems relating to the structure of orchestral music,[44] and suggested a means for expressing literary subjects by a synthesis between music and text, rather than by simple musical illustration.[124][128] These insights enabled Smetana to write the three Gothenburg symphonic poems, (Richard III, Wallenstein's Camp and Hakon Jarl),[124] works that transformed Smetana from a composer primarily of salon pieces to a modern neo-Romantic, capable of handling large-scale forces and demonstrating the latest musical concepts.[124]

From 1862 Smetana was largely occupied with opera and, apart from a few short pieces,[129] did not return to purely orchestral music before beginning Má vlast in 1872. In his introduction to the Collected Edition Score, František Bartol brackets Má vlast with the opera Libuše as "direct symbols of [the] consummating national struggle".[130] Má vlast is the first of Smetana's mature large-scale works that is independent of words, and its musical ideas are bolder than anything he had tried before.[131] To musicologist John Clapham, the cycle presents "a cross-section of Czech history and legend and impressions of its scenery, and ... conveys vividly to us Smetana's view of the ethos and greatness of the nation."[132] Despite its nationalistic associations this work has, according to Newmarch, carried Smetana's name further afield than anything he wrote, with the exception of The Bartered Bride Overture.[133] Smetana dedicated Má vlast to the city of Prague; after its first performance in November 1882 it was acclaimed by the Czech musical public as the true representation of Czech national style.[124] Its Vltava (or "The Moldau" in German) movement, depicting the river that runs through Prague towards its junction with the Elbe, is Smetana's best-known and most internationally popular orchestral composition.[134]

Opera

Smetana had virtually no precursors in Czech opera apart from František Škroup, whose works had rarely lasted beyond one or two performances.[135] In his mission to create a new canon, rather than using traditional folksong Smetana turned to the popular dance music of his youth, especially the polka, to establish his link with the vernacular.[135] He drew on existing European traditions, notably Slavonic and French,[135] but made only scarce use of arias, preferring to base his scores on ensembles and choruses.[136]

Although a follower of Wagner's reforms of the operatic genre, which he believed would be its salvation,[78] Smetana rejected accusations of excessive Wagnerism, claiming that he was sufficiently occupied with "Smetanism, for that is the only honest style!"[137] The predominantly "national" character of the first four operas is tempered by the lyrical romanticism of those written later,[138] particularly the last three, composed in the years of Smetana's deafness. The first of this final trio, The Kiss, written when Smetana was receiving painful medical treatment, is described by Newmarch as a work of serene beauty, in which tears and smiles alternate throughout the score.[139] Smetana's librettist for "The Kiss" was the young feminist Eliška Krásnohorská, who also supplied the texts for his final two operas. She dominated the ailing composer, who had no say in the subject-matter, the voice types or the balance between solos, duets and ensembles.[135] Nevertheless, critics have noted few signs of a decline in Smetana's powers in these works, while his increasing proficiency in the Czech language meant that his settings of the language are much superior to those of his earlier operas.[135]

Smetana's eight operas created the bedrock of the Czech opera repertory, but of these only The Bartered Bride is performed regularly outside the composer's homeland. After reaching Vienna in 1892,[140] and London in 1895,[141] it rapidly became part of the repertory of every major opera company worldwide. Newmarch argues that The Bartered Bride, while not a "gem of the first order", is nevertheless "a perfectly cut and polished stone of its kind."[141] Its trademark overture, which Newmarch says "lifts us off our feet with its madcap vivacity",[141] was composed in a piano version before Smetana received the draft libretto. Clapham believes that this has few precedents in the entire history of opera.[142] Smetana himself was later inclined to disparage his achievement: "The Bartered Bride was merely child's play, written straight off the reel".[141] In the view of German critic William Ritter, Smetana's creative powers reached their zenith with his third opera, Dalibor.[143]

Reception

Even in his own homeland the general public was slow to recognise Smetana. As a young composer and pianist he was well regarded in Prague musical circles, and had the approval of Liszt, Proksch and others, but the public's lack of acknowledgement was a principal factor behind his self-imposed exile in Sweden. After his return he was not taken particularly seriously,[60] and was hard put to get audiences for his new works, hence his "prophet without honour" remark after the nearly empty hall and indifferent reception of Richard III and Wallenstein's Camp at Žofín Island in January 1862.[144]

Smetana's first noteworthy public success was his initial opera The Brandenburgers in Bohemia, in 1866 when he was already 42 years old. His second opera, The Bartered Bride, survived the unfortunate mistiming of its opening night and became an enduring popular triumph. The different style of his third opera, Dalibor, closer to that of Wagnerian music drama, was not readily understood by the public and was condemned by critics who believed that Czech opera should be based on folk-song.[145][146] It disappeared from the repertory after only a handful of performances.[146] Thereafter the machinations that accompanied Smetana's tenure as Provisional Theatre conductor restricted his creative output until 1874.

.jpg)

In his final decade, the most fruitful of his compositional career despite his deafness and increasing ill-health, Smetana belatedly received national recognition. Of his later operas, The Two Widows and The Secret were warmly received,[147] while The Kiss was greeted by an "overwhelming ovation".[93] The ceremonial opera Libuše was received with thunderous applause for the composer; by this time (1881) the disputes around his music had declined, and the public was ready to honour him as the founder of Czech music.[148] Nevertheless, the first few performances in October 1882 of an evidently under-rehearsed The Devil's Wall were chaotic,[149] and the composer was left feeling "dishonoured and dispirited."[150] This disappointment was swiftly mitigated by the acclaim that followed the first performance of the complete Má vlast cycle in November: "Everyone rose to his feet and the same storm of unending applause was repeated after each of the six parts ... At the end of Blaník [the final part] the audience was beside itself and the people could not bring themselves to take leave of the composer."[151]

Smetana has a star on the "Walk of Fame" in Vienna, opened to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the opening of the Theater an der Wien.[152]

Character and reputation

Smetana's biographers describe him as physically frail and unimpressive in appearance yet, at least in his youth, he had a joie-de-vivre that women evidently found attractive.[153] He was also excitable, passionate and strong-willed, determined to make his career in music whatever the hardships, over the wishes of his father who wanted him to become a brewer or a civil servant.[19] Throughout his career he stood his ground; when under the severest of criticism for the "Wagnerism" in Dalibor he responded by writing Libuše, even more firmly based on the scale and concept of Wagnerian music drama.[154] His personal life became stressful; his marriage to Bettina was loveless, and effectively broke down altogether in the years of illness and relative poverty towards the end of his life.[155] Little of his relationships with his children is on record, although on the day that he was transferred to the asylum, Žofie was "crying as though her heart would break".[156]

There is broad agreement among most commentators that Smetana created a canon of Czech opera where none had previously existed, and that he developed a style of music in all his compositions that equated with the emergent Czech national spirit.[108][157][158] A modified view is presented by the music writer Michael Steen, who questions whether "nationalistic music" can in fact exist: "We should recognise that, whereas music is infinitely expressive, on its own it is not good at describing concrete, earthly objects or concepts."[159] He concludes that much is dependent upon what listeners are conditioned to hear.[159]

According to the musicologist John Tyrrell, Smetana's close identification with Czech nationalism and the tragic circumstances of his last years, have affected the objectivity of assessments of his work, particularly in his native land.[108] Tyrrell argues that the almost iconic status awarded to Smetana in his homeland "monumentalized him into a figure where any criticism of his life or work was discouraged" by the Czech authorities, even as late as the last part of the 20th century.[108] As a result, Tyrrell claims, a view of Czech music has been propagated that downplays the contributions of contemporaries and successors such as Dvořák, Janáček, Josef Suk and other, lesser known, composers.[108] This is at odds with perceptions in the outside world, where Dvořák is far more frequently played and much better known. Harold Schonberg observes that "Smetana was the one who founded Czech music, but Antonín Dvořák ... was the one who popularized it."[15]

Smetana has been regarded in his homeland as the father of Czech music.[160][161]

Legacy

Since Smetana's death in 1884, he and his music have become "an ever-unfolding symbol of the nation that necessarily adapts to the needs of shifting governments and administrations."[162]

On 2 March 2019, Google celebrated what would have been Smetana's 195th birthday with a Google doodle.[163]

See also

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Bedřich Smetana |

References

Notes

- "Smetana". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- {{Cite Oxford Dictionaries|Smetana, Bedřich|accessdate=13 August 2019}}

- "Smetana". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- Clapham (1972), pp. 9–11

- Large, p. 395

- Large, p. 3

- Steen, p. 694

- Ottlová, Marta; Pospíšil, Milan; Tyrrell, John; St Pierre, Kelly. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/omo/9781561592630.013.3000000151. Retrieved 7 August 2020. (subscription required)

- Clapham (1972), p. 12

- Newmarch, p. 54

- Large, p. 5

- Clapham (1972), pp. 13–14

- Large, pp. 6–7. Havlíček was also known as Karel Havlíček Borovský.

- Large, pp. 7–10

- Schonberg, p. 77

- Newmarch, p. 56

- Large, pp. 10–11

- Large, p. 17

- Large, p. 19

- Clapham (1972), pp. 15–16

- Newmarch, p. 57

- It is difficult to equate the value of a mid-19th century Austro-Hungarian gulden to 21st century dollars or sterling. A general assessment might be made on the basis of Smetana's annual salary in 1866, when he was appointed conductor of the Czech Provisional Theatre – 1,200 gulden. Clapham (1972), p. 34

- Clapham (1972), p. 17

- Large, pp. 29–35

- Clapham (1972), p. 19

- Large, p. 39

- Clapham (1972), p. 21

- Large, pp. 42–43

- Steen, p. 696

- Steen, pp. 695–96

- Ottlová, Marta. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (Section 2) (subscription required)

- Clapham (1972), p. 20

- Large, p. 48

- Large, pp. 48–49

- Large, pp. 51–54

- Large, pp. 57–62

- Clapham (1972), p. 22

- Large, pp. 63–65

- Large, pp. 67–69

- Ottlová, Marta. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (Section 3) (subscription required)

- Large, pp. 71–75

- Large. p. 78

- Clapham (1972), p. 25

- Large, p. 79

- Large, pp. 80–82

- Newmarch, p. 60

- Clapham (1972), pp. 28–30

- Large, pp. 84–94

- Large, pp. 95–97

- According to Gerald Abraham, Smetana had met Cornelius at Weimar two years previously, while the latter was working on Der Barbier. Reportedly the two composers discussed the need for "a modern type of comic opera as a complement to Wagner." Abraham, p. 29

- Large, pp. 98–99 and p. 160

- Large, p. 114

- Clapham (1980) p. 393

- Large, p. 120

- Clapham (1972), pp. 32–33

- Large, p. 126

- Large, pp. 140–43

- Ottlová, Marta. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (Section 4) (subscription required)

- Grout, p. 532

- Large, pp. 121–25

- Newmarch, p. 62

- Clapham (1972), p. 33

- Large, p. 134

- Clapham (1980), p. 394

- Large, p. 145

- Newmarch, p. 64

- Large, pp. 167–68

- Large, pp. 399–408

- Large, pp. 165–67

- Newmarch, p. 69

- Clapham (1972), pp. 34–36

- Large, pp. 209–10

- Large, p. 197

- Steen, p. 701

- Clapham (1980) p. 394

- Clapham (1972), pp. 38–40

- Newmarch, p. 71

- Newmarch, p. 65

- Clapham (1972), p. 99

- Large, p. 220

- Large, p. 171

- Clapham (1972), pp. 41–42

- Clapham (1972), pp. 43–45

- Clapham (1972), p. 44. It appears (Clapham, 1972, pp. 48–49) that this pension was withheld from time to time, causing Smetana much financial hardship.

- Large, pp. 294–95

- Large, p. 303

- Large, pp. 322–23

- Large, p. 374, from an undated letter to Bettina

- Large, p. 374

- Steen, p. 702

- Originally, the work was entitled simply Vlast ("Fatherland"). The pronoun had been added by May 1883. Large, pp. 266–67

- Clapham (1972), p. 47

- Ottlová, Marta. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (Section 5) (subscription required)

- Clapham (1972), p. 51

- Large, pp. 222–23

- Steen, pp. 702–03

- Large, pp. 370–72

- Clapham (1972), pp. 54–56

- Newmarch, p. 89

- Large, pp. 390–94

- Clapham (1972), p. 151

- Ramba, Jiří (2009). Slavné české lebky (Famous Czech Skulls) (in Czech) (2nd ed.). Prague: Galén. pp. 151–299. ISBN 978-80-7262-325-9.

- Newmarch, p. 90

- "Bedřich Smetana (1824–1884) – his life and work". Národní Muzeum. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "(2047) Smetana". (2047) Smetana In: Dictionary of Minor Planet Names. Springer. 2003. p. 166. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-29925-7_2048. ISBN 978-3-540-29925-7.

- Newmarch, pp. 90–91

- Newmarch, pp. 100–01

- Tyrrell, John. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (Section 10 (subscription required)

- See Large, pp. 425–30 Appendix G: Works in order of composition

- Schonberg, p. 78

- Large, p. 41

- Clapham (1972), pp. 58–64

- Ottlová, Marta. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (Section 9) (subscription required)

- Large, pp. 122–25

- Clapham (1972), pp. 87–89

- Large, p. 378

- Ottlová, Marta. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (Section 8)

- Clapham (1972), pp. 65–66

- Katz, Derek (1997). "Smetana's Second String Quartet: Voice of Madness or Triumph of Spirit". The Musical Quarterly. 81 (4): 516–36. doi:10.1093/mq/81.4.516. Retrieved 24 May 2009. (subscription required)

- Large, pp. 376–77

- Clapham (1972), p. 54

- Clapham (1972), pp. 68–70

- Large, p. 46

- Ottlová, Marta. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (Section 7) (subscription required)

- Newmarch, p. 59

- Large, p. 62

- Large, p. 108

- Large, p. 85

- Clapham (1972), p. 138

- Clapham (1972), pp. 76–84

- Large, p. 288

- Clapham (1972), p. 76

- Newmarch, p. 91

- Clapham, p. 80

- Tyrrell, John. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 12 May 2009. (Section 6) (subscription required)

- Grout, p. 534

- Letter to Adolf Čech 4 December 1882, quoted in Clapham (1972), p. 100

- Clapham (1972), p. 104

- Newmarch, pp. 83–84

- Tyrrell, John. "The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta)". Grove Music Online, ed. Laura Macy. Retrieved 10 June 2009. (subscription required)

- Newmarch, p. 67

- Clapham (1972), p. 94

- Newmarch, p. 72

- Large, p. 119

- Large, pp. 204–05

- Clapham (1972), p. 36

- Clapham (1972) p. 41 and p. 49

- Large, p. 348

- Clapham (1972), p. 53

- Large, p. 370

- Large, p. 268

- https://www.had.si/blog/2010/03/07/music-mile-vienna-vienna-walk-of-fame/

- Large, p. 3 and p. 10

- Large, p. 205

- Large, pp. 304–05

- Large, p. 391

- Clapham (1972), p. 123

- Large, preface p. xvii

- Steen, pp. 690–91

- Mordden, Ethan (29 May 1980). A Guide to Orchestral Music : The Handbook for Non-Musicians: The Handbook for Non-Musicians. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 204. ISBN 9780198020301. Retrieved 3 February 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- "BBC Music Magazine". BBC Magazines. 3 February 2018. p. 47. Retrieved 3 February 2018 – via Google Books.

- St Pierre, Kelly (2017). Bedřich Smetana: Myth, Music, and Propaganda. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. pp. 1–6, 109–111. ISBN 978-1-58046-510-6.

- "Bedřich Smetana's 195th Birthday". Google. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

Sources

- Abraham, Gerald (1968). Slavonic and Romantic Music. London: Faber and Faber.

- Clapham, John (1980). "Bedrich Smetana". In Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Special English edition). 17. London: Macmillan. pp. 391–403. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

- Clapham, John (1972). Smetana (Master Musicians series). London: J.M. Dent. ISBN 978-0-460-03133-2.

- Grout, Donald Jay; Wegel Williams, Hermine (2003). A Short History of Opera. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 534. ISBN 978-0-231-11958-0. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

Karel Sebor.

- Katz, Derek (1997). "Smetana's Second String Quartet: Voice of Madness or Triumph of Spirit". The Musical Quarterly. 81 (4): 516–36. doi:10.1093/mq/81.4.516. Retrieved 24 May 2009. (subscription required)

- Large, Brian (1970). Smetana. London: Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-0512-7.

- Newmarch, Rosa (1942). The Music of Czechoslovakia. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-306-77563-5. OCLC 3291947.

- Ottlová, Marta; Pospíšil, Milan; Tyrrell, John; St Pierre, Kelly. "Smetana, Bedrich". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/omo/9781561592630.013.3000000151. Retrieved 7 August 2020. (subscription required)

- Ramba, Jiří (2009). Slavné české lebky (Famous Czech Skulls) (in Czech) (2nd ed.). Prague: Galén. pp. 151–299. ISBN 978-80-7262-325-9.

- Schonberg, Harold C. (1975). The Lives of the Great Composers, Vol. II. London: Futura Publications. ISBN 978-0-86007-723-7.

- St Pierre, Kelly (2017). Bedřich Smetana: Myth, Music, and Propaganda. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-510-6.

- "Stálé expozice Národního muzea" (in Czech). Národní muzeum. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 6 June 2009.

- Steen, Michael (2003). The Lives and Times of the Great Composers. London: Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84046-679-9.

- Tyrrell, John. "The Bartered Bride (Prodaná nevěsta)". In Laura Macy (ed.). Grove Music Online. (subscription required)

- Tyrrell, John. "Smetana, Bedrich". In Laura Macy (ed.). Grove Music Online. (subscription required)

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Bedřich Smetana |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Bedřich Smetana. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bedřich Smetana. |

- Bedřich Smetana at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Free scores by Smetana at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Bedrich Smetana on IMDb