Self-immolation

Self-immolation is the act of killing oneself, typically for political or religious reasons, particularly by burning. It is often used as an extreme form of protest or in acts of martyrdom. It has a centuries-long recognition as the most extreme form of protest achieved by humankind.

| Suicide |

|---|

|

Social aspects |

|

Related phenomena |

|

Organizations |

Etymology

The English word immolation originally meant (1534) "killing a sacrificial victim; sacrifice" and came to figuratively mean (1690) "destruction, especially by fire." Its etymology was from Latin immolare "to sprinkle with sacrificial meal (mola salsa); to sacrifice" in ancient Roman religion. Self-immolation "setting oneself on fire, especially as a form of protest" was first recorded in Lady Morgan's France (1817).[1][2]

History

See: List of political self-immolations

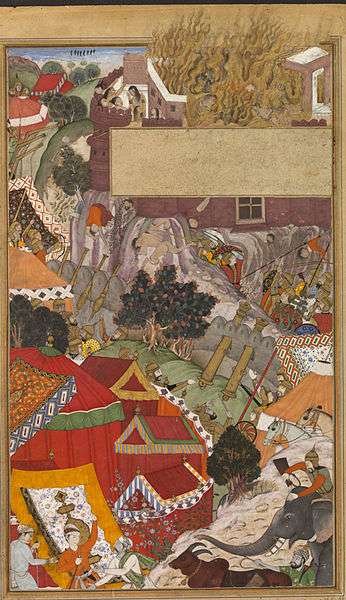

Self-immolation is tolerated by some elements of Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism, and it has been practiced for many centuries, especially in India, for various reasons, including jauhar, political protest, devotion, and renouncement. A historical example includes the practice of Sati when the Hindu goddess of the same name (see also Daksayani) legendarily set herself on fire after her father insulted her. Certain warrior cultures, such as those of the Charans and Rajputs, also practiced self-immolation.

The act of sacrificing one's own body, though not by fire, is a component of two well-known stories found in the ancient Buddhist text known as the Jataka Tales, which, according to Buddhist tradition, gives accounts of past incarnations of the Buddha. In the "Hungry Tigress" Jataka, Prince Sattva looked down from a cliff and saw a starving tigress that was going to eat her newborn cubs, and compassionately sacrificed his body in order to feed the tigers and spare their lives. In the "Sibi Jataka", King Śibi, or Shibi, was renowned for selflessness, and the gods Śakra and Vishvakarman tested him by transforming into a hawk and a dove. The dove fell on the king's lap while trying to escape the hawk, and sought refuge. Rather than surrender the dove, Śibi offered his own flesh equivalent in weight to the dove, and the hawk agreed. They had rigged the balance scale, and King Śibi continued cutting off his flesh until half his body was gone, when the gods revealed themselves, restored his body, and blessed him.

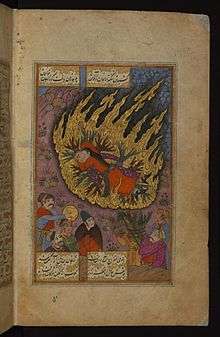

The Bodhisattva "Medicine King" (Bhaishajyaraja) chapter of the Lotus Sutra was associated with auto-cremation. In a previous life, 'Medicine King' Bodhisattva burnt his body as a supreme offering to the Buddha.[3][4][5] The Lotus Sutra describes the Bodhisattva Sarvarupasamdarsana drinking scented oils, wrapping his body in an oil-soaked cloth, and burning himself. His body flamed for 1,200 years, he was reincarnated, burned off his forearms for 72,000 years, which enabled many to achieve enlightenment, and his arms were miraculously restored.[6]

Zarmanochegas was a monk of the Sramana tradition (possibly, but not necessarily a Buddhist) who, according to ancient historians such as Strabo and Dio Cassius, met Nicholas of Damascus in Antioch around 13 ACE and burnt himself to death in Athens shortly thereafter.[7][8]

Self-immolation has a long history in Chinese Buddhism. The relevant terms are: wangshen Chinese: 亡身 "lose the body" or Chinese: 忘身 "forget the body", yishen Chinese: 遺身 "abandon the body", and sheshen Chinese: 捨身 "give up the body". James A. Benn explains the semantic range of Chinese Buddhist self-immolation.

But "abandoning the body" also covers a broad range of more extreme acts (not all of which necessarily result in death): feeding one's body to insects; slicing off one's flesh; burning one's fingers or arms; burning incense on the skin; starving, slicing, or drowning oneself; leaping from cliffs or trees; feeding one's body to wild animals; self-mummification (preparing for death so that the resulting corpse is impervious to decay); and of course, auto-cremation.[9]

The monk Fayu 法羽 (d. 396) carried out the earliest recorded Chinese self-immolation.[10] He first informed the "illegitimate" prince Yao Xu 姚緒—brother of Yao Chang who founded the non-Chinese Qiang state Later Qin (384-417)—that he intended to burn himself alive. Yao tried to dissuade Fayu, but he publicly swallowed incense chips, wrapped his body in oiled cloth, and chanted while setting fire to himself. The religious and lay witnesses were described as being "full of grief and admiration."

Following Fayu's example, many Buddhist monks and nuns have used self-immolation for political purposes. Based upon analysis of Chinese historical records from the 4th to the 20th centuries, Benn discovered, "Although some monks did offer their bodies in periods of relative prosperity and peace, we have seen a marked coincidence between acts of self-immolation and times of crisis, especially when secular powers were hostile towards Buddhism."[11] For example, Daoxuan's (c. 667) Xu Gaoseng Zhuan(續高僧傳, or Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks) records five monastics who self-immolated on the Zhongnan Mountains in response to the 574–577 persecution of Buddhism by Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou (known as the "Second Disaster of Wu").[12]

While self-immolation practices in China were based upon Indian Buddhist traditions, they acquired some distinctively Chinese aspects. An "unburned tongue" (cf. Anthony of Padua), which supposedly remained pink and moist owing to self-immolation while chanting the Lotus Sutra, was based on the belief in Śarīra "Buddhist relics; purportedly from a master's remains after cremation".[13] "Burning off fingers" was a kind of gradual self-immolation, often in commemoration of relics or textual recitations. The Tang Dynasty monk Wuran 無染 (d. c. 840) had a spiritual vision in which Manjusri told him to support the Buddhist community on Mount Wutai. After organizing meals for one million monks, Wuran burned off a finger in sacrifice, and eventually after ten million meals, had burned off all his fingers.[14] Xichen 息塵 (d. c. 937; with two fingers left) became a favorite of Emperor Gaozu of Later Jin for practicing finger burning to memorialize sutra recitations.[15] "Buddhist mummies" refers to monks and nuns who practiced self-mummification through extreme self-mortification, for instance, Daoxiu 道休 (d. 629).[16] "Spontaneous human combustion" was a rare form of self-immolation that Buddhists associated with samādhi "consciously leaving one's body at the time of enlightenment". The monk Ningyi 寧義 (d. 1583) stacked up firewood to burn himself, but, "As soon the torch was raised, his body started to burn 'like a rotten root' and was soon completely consumed. A wise person declared, 'He has entered the fiery samādhi." [17]

James A. Benn concludes that, "for many monks and laypeople in Chinese history, self-immolation was a form of Buddhist practice that modeled and expressed a particular bodily or somatic path that led towards Buddhahood."[11]

Jan Yun-Hua explains the medieval Chinese Buddhist precedents for self-immolation.[18]

Relying exclusively on authoritative Chinese Buddhist texts and, through the use of these texts, interpreting such acts exclusively in terms of doctrines and beliefs (e.g., self-immolation, much like an extreme renunciant might abstain from food until dying, could be an example of disdain for the body in favor of the life of the mind and wisdom) rather than in terms of their socio-political and historical context, the article allows its readers to interpret these deaths as acts that refer only to a distinct set of beliefs that happen to be foreign to the non-Buddhist.[18]

Jimmy Yu has shown that self-immolation cannot be interpreted based on Buddhist doctrine and beliefs alone but the practice must be understood in the larger context of the Chinese religious landscape. He examines many primary sources from the 16th and 17th century and demonstrates that bodily practices of self-harm, including self-immolation, was ritually performed not only by Buddhists but also by Daoists and literati officials who either exposed their naked body to the sun in a prolonged period of time as a form of self-sacrifice or burned themselves as a method of procuring rain.[19] In other words, self-immolation was a sanctioned part of Chinese culture that was public, scripted, and intelligible both to the person doing the act and to those who viewed and interpreted it, regardless of their various religion affiliations.

The Japanese ritual suicide seppuku (also called harakiri — ritual disembowelment) is another example of "self-immolation".

During the Great Schism of the Russian Church, entire villages of Old Believers burned themselves to death in an act known as "fire baptism" (self-burners: soshigateli).[20] Scattered instances of self-immolation have also been recorded by the Jesuit priests of France in the early 17th century. However, their practice of this was not intended to be fatal: they would burn certain parts of their bodies (limbs such as the forearm or the thigh) to symbolise the pain Jesus endured while upon the cross. A 1973 study by a prison doctor suggested that people who choose self-immolation as a form of suicide are more likely to be in a "disturbed state of consciousness", such as epilepsy.[21]

Political protest

The Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam saw the persecution of the country's majority religion under the administration of Catholic president Ngô Đình Diệm. Several Buddhist monks, including the most famous case of Thích Quảng Đức, immolated themselves by fire in protest. An important source of inspiration for the monks and nuns who self-immolated is the twenty-third chapter of the Lotus Sutra which recounts the life story of Bodhisattva Medicine King. In this section of the Sutra, Medicine King demonstrates his insight into Śūnyatā and the selfless nature of all things by ritualistically setting his own body aflame, which burned for 1,200 years to demonstrate the immeasurable power of the Buddhadharma. Thich Nhat Hanh adds: "The bodhisattva shone his light about him so that everyone could see as he could see, giving them the opportunity to see the deathless nature of the ultimate."[22]

The widespread coverage of the self-immolations of the Buddhist monks in mid-20th-century Western media established the practice as a type of a political protest in the Western mind. Self-immolations are often public and political events that catch the attention of the news media through their dramatic means. They are seen as a type of altruistic suicide for a collective cause, and are not intended to inflict physical harm on others or cause material damage.[23] They attract attention to a cause and those who undergo the act are glorified in martyrdom. Fire immolation does not guarantee death for the burned.

The example set by self-immolators in the mid 20th century did spark numerous similar acts between 1963 and 1971, most of which occurred in Asia and the United States in conjunction with protests opposing the Vietnam War. Researchers counted almost 100 self-immolations covered by The New York Times and The Times.[24] In 1968 the practice spread to the Soviet bloc with the self-immolation of Polish accountant and Armia Krajowa veteran Ryszard Siwiec, as well as those of two Czech students, Jan Palach and Jan Zajíc, and of toolmaker Evžen Plocek, in protest against the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia. As a protest against Soviet rule in Lithuania, 19-year-old Romas Kalanta set himself on fire in Kaunas. In 1978 Ukrainian dissident and former political prisoner Oleksa Hirnyk burnt himself near the tomb of the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko protesting against the russification of Ukraine under Soviet rule.

The practice continues, notably in India: as many as 1,451 and 1,584 self-immolations were reported there in 2000 and 2001, respectively.[25] A particularly high wave of self-immolation in India was recorded in 1990 protesting the Reservation in India.[23] Tamil Nadu has the highest number of self-immolations in India to date.

In Iran, most self-immolations have been performed by citizens protesting the tempestuous changes brought upon after the Iranian Revolution. Many of which have gone largely unreported by regime authority, but have been discussed and documented by established witnesses. Provinces that were involved more intensively in postwar problems feature higher rates of self-immolation.[26] These undocumented demonstrations of protest are deliberated upon worldwide, by professionals such as Iranian historians who appear on international broadcasts such as Voice of America, and use the immolations as propaganda to direct criticism towards the Censorship in Iran. One specifically well documented self-immolation transpired in 1993, 14 years after the revolution, and was performed by Homa Darabi, a self-proclaimed political activist affiliated with the Nation Party of Iran. Darabi is known for her political self-immolation in protest to the compulsory hijab. Self-immolation protests continue to take place against the regime to this day. Most recently accounted for is the September 2019 Death of Sahar Khodayari, protesting a possible sentence of six months in prison for having tried to enter a public stadium to watch a football game, against the national ban against women at such events. One month after her death, Iranian women were allowed to attend a soccer match in Iran for the first time in 40 years.[27][28]

Since 2009, there have been, as of June 2017, 148 confirmed and two disputed[29][30] self-immolations by Tibetans, with most of these protests (some 80%) ending in death. The Dalai Lama has said he does not encourage the protests, but he has spoken with respect and compassion for those who engage in self-immolation. The Chinese government, however, claims that he and the exiled Tibetan government are inciting these acts.[31] In 2013, the Dalai Lama questioned the effectiveness of self-immolation as a demonstration tactic. He has also expressed that the Tibetans are acting of their own free will and stated that he is powerless to influence them to stop carrying out immolation as a form of protest.[32]

A wave of self-immolation suicides occurred in conjunction with the Arab Spring protests in the Middle East and North Africa, with at least 14 recorded incidents. These suicides assisted in inciting the Arab Spring, including the 2010–2011 Tunisian revolution, the main catalyst of which was the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, the 2011 Algerian protests (including many self-immolations in Algeria), and the 2011 Egyptian revolution. There have also been suicide protests in Saudi Arabia, Mauritania, Syria[33][34]

See also

- Buddhist views on suicide

- Buddhist devotion#Other practices

- List of political self-immolations

- Self-immolations in Tunisia

- Self-immolation protests by Tibetans in China

References

- The Oxford English Dictionary, 2009, 2nd ed., v. 4.0, Oxford University Press.

- immolate, Oxford Dictionaries.

- Williams, Paul (1989), Mahāyāna Buddhism: the doctrinal foundations, 2nd Edition, Routledge, p. 160, ISBN 9780415356534

- Benn, James A (2007), Burning for the Buddha, University of Hawaii Press, p. 59, ISBN 0824823710

- Ohnuma, Reiko (1998), "The Gift of the Body and the Gift of Dharma", History of Religions, 37 (4): 324, JSTOR 3176401

- (Kubo, Tsugunari; Yuyama, Akira, trans. (2007). The Lotus Sutra (PDF). Berkeley, Calif.: Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research. pp. 280–284. ISBN 978-1-886439-39-9. Archived from the original on 21 May 2015.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Strabo, xv, 1, on the immolation of the Sramana in Athens (Paragraph 73).

- Dio Cassius, liv, 9; see also Halkias, Georgios "The Self-immolation of Kalanos and other Luminous Encounters among Greeks and Indian Buddhists in the Hellenistic world." Journal of the Oxford Centre for Buddhist Studies, Vol. VIII, 2015: 163–186

- Benn, James A. (2007), Burning for the Buddha: self-immolation in Chinese Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, 9–10.

- Benn (2007), 33–34.

- (2007), 199.

- Benn (2007), 80–82.

- Benn (2007), 144–147.

- Benn (2007), 135–36.

- Benn (2007), 149–150.

- Benn (2007), 97.

- Benn (2007), 179.

- thichnhattu. "The Self-Immolation of Thich Quang Duc". Buddhismtoday.com. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- Yu, Jimmy (2012), Sanctity and Self-Inflicted Violence in Chinese Religions, 1500–1700, Oxford University Press, 115–130.

- Coleman, Loren (2004). The Copycat Effect: How the Media and Popular Culture Trigger the Mayhem in Tomorrow's Headlines. New York: Paraview Pocket-Simon and Schuster. p. 46. ISBN 0-7434-8223-9.

- Prins, Herschel (2010). Offenders, Deviants or Patients?: Explorations in Clinical Criminology. Taylor & Francis. p. 291.

Topp ... suggested that such individuals ... have some capacity for splitting off feelings from consciousness.... One imagines that shock and asphyxiation would probably occur within a very short space of time so that the severe pain ... would not have to be endured for too long.

- Nhá̂t Hạnh. (2003). Opening the heart of the cosmos: Insights on the Lotus Sutra. Berkeley, CA: Parallax Press. p. 144.

- Biggs, Michael (2005). "Dying Without Killing: Self-Immolations, 1963–2002" (PDF). In Diego Gambetta (ed.). Making Sense of Suicide Missions. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929797-9.

- Maris, Ronald W.; Alan Lee Berman; Morton M. Silverman; Bruce Michael Bongar (2000). Comprehensive textbook of suicidology. Guilford Press. p. 306. ISBN 978-1-57230-541-0.

- Coleman, Loren (2004). The Copycat Effect: How the Media and Popular Culture Trigger the Mayhem in Tomorrow's Headlines. New York: Paraview Pocket-Simon and Schuster. p. 66. ISBN 0-7434-8223-9.

- "National Library of Medicine: Self-immolation in Iran".

- "Iranian female football fan who self-immolated outside court dies: official".

- "Iran football: Women attend first match in decades".

- Free Tibet. "Tibetan Monk Dies After Self-Immolating In Eastern Tibet". Retrieved 20 May 2017.

- "Tibetan dies after self-immolation, reports say". Fox News. 21 July 2013.

- "Teenage monk sets himself on fire on 53rd anniversary of failed Tibetan uprising". London: Telegraph. 13 March 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- "Dalai Lama doubts effect of Tibetan self-immolations". The Daily Telegraph. London. 13 June 2013.

- "Self-immolation spreads across Mideast inspiring protest".

- "Second Algerian dies from self-immolation: official".

Bibliography

- King, Sallie B. (2000). They Who Burned Themselves for Peace: Quaker and Buddhist Self-Immolators during the Vietnam War, Buddhist-Christian Studies 20, 127-150 – via JSTOR (subscription required)

- Kovan, Martin (2013). Thresholds of Transcendence: Buddhist Self-immolation and Mahāyānist Absolute Altruism, Part One. Journal of Buddhist Ethiks 20, 775-812

- Kovan, Martin (2014). Thresholds of Transcendence: Buddhist Self-immolation and Mahāyānist Absolute Altruism, Part Two. Journal of Buddhist Ethiks 21, 384-430

- Patler, Nicholas. Norman's Triumph: the Transcendent Language of Self-Immolation Quaker History, Fall 2015,18-39.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Self-immolation. |