Closely Watched Trains

Closely Watched Trains (Czech: Ostře sledované vlaky) is a 1966 Czechoslovak film directed by Jiří Menzel and is one of the best-known products of the Czechoslovak New Wave. It was released in the United Kingdom as Closely Observed Trains. It is a coming-of-age story about a young man working at a train station in German-occupied Czechoslovakia during World War II. The film is based on a 1965 novel by Bohumil Hrabal. It was produced by Barrandov Studios and filmed on location in Central Bohemia. Released outside Czechoslovakia during 1967, it won the Best Foreign Language Oscar at the 40th Academy Awards in 1968.[2]

| Closely Watched Trains | |

|---|---|

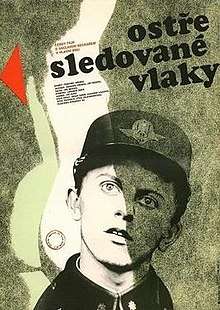

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jiří Menzel |

| Produced by | Zdeněk Oves |

| Screenplay by | Jiří Menzel |

| Based on | Closely Watched Trains by Bohumil Hrabal |

| Starring | Václav Neckář Jitka Bendová Josef Somr Vlastimil Brodský Vladimír Valenta |

| Music by | Jiří Šust |

| Cinematography | Jaromír Šofr |

| Edited by | Jiřina Lukešová |

Production company | Barrandov Studios Ceskoslovensky Film |

| Distributed by | Ústřední půjčovna filmů |

Release date |

|

Running time | 92 minutes |

| Country | Czechoslovakia |

| Language | Czech German |

| Box office | $1,500,000 (US/ Canada)[1] |

Plot

The young Miloš Hrma, who speaks with misplaced pride of his family of misfits and malingerers, is engaged as a newly trained station guard in a small railway station during the Second World War and the German occupation of Czechoslovakia. He admires himself in his new uniform, and looks forward, like his prematurely retired railwayman father, to avoiding real work. The sometimes pompous stationmaster is an enthusiastic pigeon-breeder with a kind wife, but is envious of the train dispatcher Hubička's success with women. Miloš holds an as-yet platonic love for the pretty, young conductor Máša. The experienced Hubička presses for details of their relationship and realizes that Miloš is still a virgin.

The idyll of the railway station is periodically disturbed by the arrival of the councillor, Zedníček, a Nazi collaborator, who spouts propaganda at the staff without success. At her initiative, Máša spends the night with Miloš, but in his youthful excitability he ejaculates prematurely before achieving penetration and then is unable to perform sexually; and the next day, despairing, he attempts suicide. He is saved, and a young doctor explains to him that ejaculatio praecox is normal at Miloš's age. The doctor recommends Miloš to "think of something else" (at which point Miloš volunteers an interest in football), and to seek the assistance of an experienced woman. During the nightshift, Hubička flirts with the young telegraphist, Zdenička, and imprints her thighs and buttocks with the office's rubber stamps. Her mother sees the stamps and complains to Hubička's superiors, and the ensuing scandal helps to frustrate the stationmaster's ambition of being promoted to inspector.

The Germans and their collaborators are on edge, since their trains are being attacked by the partisans. A glamorous Resistance agent (a circus artist in peacetime), code-named Viktoria Freie, delivers a time bomb to Hubička for use in blowing up a large ammunition train. At Hubička's request, the "experienced" Viktoria also helps Miloš to resolve his sexual problem.

The next day, at the crucial moment when the ammunition train is approaching, Hubička is caught up in a farcical disciplinary hearing, overseen by Zedníček, over his rubber-stamping of Zdenička's backside. In Hubička's place, Miloš, liberated by his experience with Viktoria from his former passivity, takes the time bomb and drops it from a semaphore gantry, that extends transversely above the tracks, onto the train. A machine-gunner on the train, spotting Miloš, sprays him with bullets, and his body falls onto the train. With the Nazi collaborator Zedníček winding up the disciplinary hearing, dismissing the Czech people as "nothing but laughing hyenas" (a phrase actually employed by the senior Nazi official Reinhard Heydrich[3]), the implicit retort to his jibe comes in the form of a huge series of explosions that destroys the train.[4] Now Hubička and the other railwaymen are indeed laughing — to express their joy at the blow to the Nazi occupiers — and it is left to a wistful Máša to pick up Miloš's uniform cap, hurled across the station by the power of the blast.

Cast

- Václav Neckář as Miloš Hrma

- Vlastimil Brodský as councilor Zedníček

- Jitka Bendová as conductor Máša

- Josef Somr as train dispatcher Hubička

- Libuše Havelková as stationmaster's wife

- Vladimír Valenta as stationmaster

- Jitka Zelenohorská as telegraphist Zdenička

- Naďa Urbánková as Viktoria Freie

- Jiří Menzel as Doctor Brabec

Production

The film is based on a 1965 novel of the same name by the noted Czech author Bohumil Hrabal, whose work Jiří Menzel had already begun to adapt in 1965 in the short The Death of Mr. Balthazar, a segment from the anthology film of Hrabal stories Pearls from the Deep.[3] Barrandov Studios first offered the film project to the more experienced directors Evald Schorm and Vera Chytilova, neither of whom saw a way to adapt the book to film,[5] before offering it to Menzel as his feature-film debut. Menzel and Hrabal worked together closely on the script, making a number of modifications to the novel.[5] Menzel's first choice for the lead role of Miloš was Vladimír Pucholt, who however was occupied filming Jiří Krejčík's Svatba jako řemen. At one point Menzel considered playing the role himself, but concluded that at almost 28 he was too old. Fifteen non-professional actors were tested, before the wife of Ladislav Fikar (a poet and publisher) came up with the suggestion of the pop singer Václav Neckář.[5] Menzel has related that he himself took on the cameo role of the doctor only at the last minute after the actor originally cast failed to show up for shooting. Filming began in late February and lasted until the end of April 1966. Locations were used in and around the station building in Loděnice.[6] The association between Menzel and Hrabal was to continue. They collaborated on the script of the long-banned film Larks on a String, filmed in 1969 but not released until 1990.

Reception

The film premiered in Czechoslovakia on 18 November 1966.[7] Release outside Czechoslovakia took place in the following year.

Critical response

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called Closely Watched Trains "as expert and moving in its way as was Jan Kadár's and Elmar Klos's The Shop on Main Street or Milos Forman's Loves of a Blonde," two roughly contemporary films from Czechoslovakia. Crowther wrote:

What it appears Mr. Menzel is aiming at all through his film is just a wonderfully sly, sardonic picture of the embarrassments of a youth coming of age in a peculiarly innocent yet worldly provincial environment. ... The charm of his film is in the quietness and slyness of his earthy comedy, the wonderful finesse of understatements, the wise and humorous understanding of primal sex. And it is in the brilliance with which he counterpoints the casual affairs of his country characters with the realness, the urgency and significance of those passing trains.[8]

Variety's reviewer wrote:

The 28-year-old Jiri Menzel registers a remarkable directorial debut. His sense for witty situations is as impressive as his adroit handling of the players. A special word of praise must go to Bohumil Hrabal, the creator of the literary original; the many amusing gags and imaginative situations are primarily his. The cast is composed of wonderful types down the line.[9]

In his study of the Czechoslovak New Wave, Peter Hames places the film in a broader context, connecting it inter alia to the most famous anti-hero of Czech literature, Jaroslav Hašek's The Good Soldier Švejk, a fictional World War 1 soldier whose artful evasion of duty and undermining of authority are sometimes held to epitomize characteristic Czech qualities:

In its attitudes, if not its form, Closely Observed Trains is the Czech film that comes closest to the humour and satire of The Good Soldier Švejk, not least because it is prepared to include the reality of the war as a necessary aspect of its comic vision. The attack on ideological dogmatism, bureaucracy and anachronistic moral values undoubtedly strikes wider targets than the period of Nazi Occupation. However, it would be wrong to reduce the film to a coded reflection on contemporary Czech society: the attitudes and ideas derive from the same conditions that originally inspired Hašek. Insofar as these conditions recur, under the Nazi Occupation or elsewhere, the response will be the same.[5]

Awards and honors

The film won several international awards:

- The Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, awarded in 1968 for films released in 1967[10]

- The Grand Prize at the 1966 Mannheim-Heidelberg International Filmfestival

- A nomination for the 1968 BAFTA Awards for Best Film and Best Soundtrack

- A nomination for the 1968 DGA Award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures

- A nomination for the 1967 Golden Globe for Best Foreign-Language Foreign Film

See also

- Czechoslovak New Wave

- List of submissions to the 40th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of Czechoslovakia submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

References

- Notes

- "Big Rental Films of 1968", Variety, 8 January 1969 p 15. Please note this figure is a rental accruing to distributors.

- "The 40th Academy Awards (1968) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 2011-11-12.

- Hames, Peter. The Czechoslovak New Wave. Second Edition, 2005, London and New York, Wallflower Press.

- Collective of editors (2004). Český hraný film IV./Czech Feature Film IV. (1961-1970). Prague: Národní filmový archiv. pp. 339–344. ISBN 80-7004-115-3.

- Hames.

- Taussig, Pavel (2010-05-07). "Ostře sledované vlaky". instinkt.tyden.cz (in Czech). Empresa Media. Archived from the original on 2012-03-29. Retrieved 2011-07-08.

- "Ostře sledované vlaky". Česko-Slovenská filmová databáze (in Czech). POMO Media Group. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- Crowther, Bosley (1967-10-16). "Closely Watched T/rains (1966)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- Staff writer (1966). "Ostre Sledovane Vlaky". Variety. Retrieved 2011-10-07.

- "Closely Watched Trains" Wins Foreign Language Film: 1968 Oscars

- Bibliography

- Hames, Peter. The Czechoslovak New Wave. Second Edition, 2005, London and New York, Wallflower Press.

- Škvorecký J. Jiří Menzel and the history of the «Closely watched trains». Boulder: East European Monographs, 1982

Further reading

- Menzel, Jiri & Hrabal, Bohumil (1971) Closely Observed Trains. (Modern Film Scripts.) London: Lorrimer

External links

- Closely Watched Trains on IMDb

- Closely Watched Trains at AllMovie

- Closely Watched Trains an essay by Richard Schickel at the Criterion Collection

- Closely Watched Trains on Criterion Channel