Kingdom of Germany

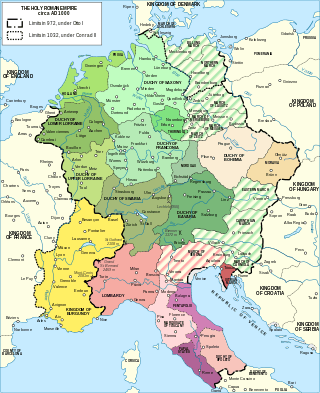

The Kingdom of Germany or German Kingdom (Latin: regnum Teutonicorum "Kingdom of the Teutons", regnum Teutonicum "Teutonic Kingdom",[1] regnum Alamanie[2]) is a historical name sometimes used to denote the mostly Germanic-speaking East Francia, which was formed by the Treaty of Verdun in 843, and was ruled by the Frankish Carolingian dynasty until 911, after which the kingship was elective. The initial electors were the German rulers of the stem duchies, who generally chose one of their own. After 962, when Otto I was crowned emperor, East Francia formed the bulk of the Holy Roman Empire along with Italy; it later included Bohemia (after 1004) and the Kingdom of Burgundy (after 1032).

Like medieval England and medieval France, medieval Germany consolidated from a conglomerate of smaller tribes, nations or polities by the High Middle Ages.[3] The term rex teutonicorum ("king of the Germans") first came into use in Italy around the year 1000.[4] It was popularized by the chancery of Pope Gregory VII during the Investiture Controversy (late 11th century), perhaps as a polemical tool against Emperor Henry IV.[5] In the twelfth century, in order to stress the imperial and transnational character of their office, the emperors began to employ the title rex Romanorum (king of the Romans) on their election (by the prince-electors, seven German bishops and noblemen). Distinct titulature for Germany, Italy and Burgundy, which traditionally had their own courts, laws, and chanceries,[6] gradually dropped from use.

The Archbishop of Mainz was ex officio arch-chancellor of Germany, as his colleagues the Archbishop of Cologne and Archbishop of Trier were, respectively, arch-chancellors of Italy and Burgundy. These titles continued in use until the end of the empire, but only the German chancery actually existed.[7]

Therefore, throughout the Middle Ages, the convention was that the (elected) king of Germany was also Emperor of the Romans. His title was royal (king of the Germans, or from 1237 king of the Romans) from his election to his coronation in Rome by the Pope; thereafter, he was emperor. After the death of Frederick II in 1250, the trend toward a "more clearly conceived German kingdom" found no real consolidation.[8] The title of "king of the Romans" became less and less reserved for the emperor-elect but uncrowned in Rome; the emperor-elect was either known as German king or simply styled himself "imperator" (see the example of Louis IV below). The reign was dated to begin either on the day of election (Philip of Swabia, Rudolf of Habsburg) or the day of the coronation (Otto IV, Henry VII, Louis IV, Charles IV). The election day became the starting date permanently with Sigismund.

Nevertheless, there are relatively few references to a German realm distinct from the Holy Roman Empire.[8]

Background

Carolingian East Francia, 843–911

The tripartite division of the Carolingian Empire effected by the Treaty of Verdun was challenged very early on with the death of the Emperor Lothair I in 855. He had divided his kingdom of Middle Francia between his three sons and immediately the northernmost of the three divisions, Lotharingia, was disputed between the kings of East and West Francia. The war over Lotharingia lasted until 925. Lothair II of Lotharingia died in 869 and the Treaty of Meerssen (870) divided his kingdom between East and West Francia, but the West Frankish sovereigns relinquished their rightful portion to East Francia by the Treaty of Ribemont in 880. Ribemont determined the border between France and Germany until the fourteenth century. The Lotharingian nobility tried to preserve their independence of East of West Frankish rule by switching allegiance at will with the death of king Louis the Child in 911, but in 925 Lotharingia was finally ceded to East Francia by Rudolph of West Francia and it thereafter formed the Duchy of Lorraine within the East Frankish kingdom.

Louis the German was known at the time as "Rex Germaniae" (King of Germany) as his brother was called King of Gaul. This was meant to distinguish the different parts of a theoretically single Frankish kingdom, although it is not known if this was meant to signify anything further.[9]

East Francia was itself divided into three parts at the death of Louis the German (875). Traditionally referred to as "Saxony", "Bavaria", and "Swabia" (or "Alemannia"), these kingdoms were ruled by the three sons of Louis in cooperation and were reunited by Charles the Fat in 882. Regional differences existed between the peoples of the different regions of the kingdom and each region could be readily described by contemporaries as a regnum, though each was certainly not a kingdom of its own. The common Germanic language and the tradition of common rule dating to 843 preserved political ties between the different regna and prevented the kingdom from coming apart after the death of Charles the Fat. The work of Louis the German to maintain his kingdom and give it a strong royal government also went a long way to creating an East Frankish (i.e. German) state.

Stem duchies

Within East Francia were large duchies, sometimes called kingdoms (regna) after their former status, which had a certain level of internal solidarity. Early among these were Saxony and Bavaria, which had been conquered by Charlemagne.[10] In German historiography they are called the jüngere Stammesherzogtümer, or "younger stem duchies",[11] The conventional five "younger stem duchies" of the Holy Roman Empire are Saxony, Bavaria, Franconia, Swabia and Lotharingia. Thuringia, while one of the "old stem duchies", is not counted among the young stem duchies because it had been absorbed into Saxony in 908, before the foundation of the Holy Roman Empire.

The conventional term "younger" serves to distinguish them from the (poorly documented) duchies under the Merovingian monarchs. Herwig Wolfram (1971) denied any real distinction between older and younger stem duchies, or between the stem duchies of Germany and similar territorial principalities in other parts of the Carolingian empire:

I am attempting to refute the whole hallowed doctrine of the difference between the beginnings of the West-Frankish, "French", principautés territoriales, and the East-Frankish, "German," stem-duchies ... Certainly, their names had already appeared during the Migrations. Yet, their political institutional, and biological structures had more often than not thoroughly changed. I have, moreover, refuted the basic difference between the so-called älteres Stammesfürstentum [older tribal principality] and jüngeres Stammesfürstentum [younger tribal principality], since I consider the duchies before and after Charlemagne to have been basically the same Frankish institution ...[12]

There has been debate in modern German historiography over the sense in which these duchies were "tribal", as in a people sharing a common descent ("stem"), being governed as units over long periods of time, sharing a tribal sense of solidarity, shared customs, etc.[10] In the context of modern German nationalism, Gerd Tellenbach (1939) emphasised the role of feudalism, both of the kings in the formation of the German kingdom and of the dukes in the formation of the stem duchies, against Martin Lintzel and Walter Schlesinger, who emphasised the role of the individual "stems" or "tribes" (Stämme).[13] The existence of a "tribal" self-designation among Saxons and Bavarians can be asserted for the 10th and 12th centuries, respectively, although they may have existed much earlier.[10]

After the death of the last Carolingian, Louis the Child, in 911, the stem duchies acknowledged the unity of the kingdom. The dukes gathered and elected Conrad I to be their king. According to Tellenbach's thesis, the dukes created the duchies during Conrad's reign.[14] No duke attempted to set up an independent kingdom. Even after the death of Conrad in 918, when the election of Henry the Fowler was disputed, his rival, Arnulf, Duke of Bavaria, did not establish a separate kingdom but claimed the whole,[15] before being forced by Henry to submit to royal authority.[10] Henry may even have promulgated a law stipulating that the kingdom would thereafter be united.[10] Arnulf continued to rule it like a king even after his submission, but after his death in 937 it was quickly brought under royal control by Henry's son Otto the Great.[11] The Ottonians worked to preserve the duchies as offices of the crown, but by the reign of Henry IV the dukes had made them functionally hereditary.[16]

Emergence of "German" terminology

Ottonians

The eastern division of the Treaty of Verdun was called the regnum Francorum Orientalium or Francia Orientalis: the Kingdom of the Eastern Franks or simply East Francia. It was the eastern half of the old Merovingian regnum Austrasiorum. The "east Franks" (or Austrasians) themselves were the people of Franconia, which had been settled by Franks. The other peoples of East Francia were Saxons, Frisians, Thuringii, and the like, referred to as Teutonici (or Germans) and sometimes as Franks as ethnic identities changed over the course of the ninth century.

An entry in the Annales Iuvavenses (or Salzburg Annals) for the year 919, roughly contemporary but surviving only in a twelfth-century copy, records that Baiuarii sponte se reddiderunt Arnolfo duci et regnare ei fecerunt in regno teutonicorum, i.e. that "Arnulf, Duke of the Bavarians, was elected to reign in the Kingdom of the Germans".[17] Historians disagree on whether this text is what was written in the lost original; also on the wider issue whether the idea of the Kingdom as German, rather than Frankish, dates from the tenth or the eleventh century;[18] but the idea of the kingdom as "German" is firmly established by the end of the eleventh century.[19] In the tenth century, German writers already tended toward using modified terms such as "Francia and Saxony" or "land of the Teutons".[20]

Any firm distinction between the kingdoms of Eastern Francia and Germany is to some extent the product of later retrospection. It is impossible to base this distinction on primary sources, as Eastern Francia remains in use long after Kingdom of Germany comes into use.[21] The 12th century imperial historian Otto von Freising reported that the election of Henry the Fowler was regarded as marking the beginning of the kingdom, though Otto himself disagreed with this. Thus:

From this point some reckon a kingdom of the Germans as supplanting that of the Franks. Hence, they say that Pope Leo in the decrees of the popes, called Henry's son Otto the first king of the Germans. For that Henry of whom we are speaking refused, it is said, the honor offered by the supreme pontiff. But it seems to me that the kingdom of the Germans — which today, as we see, has possession of Rome — is a part of the kingdom of the Franks. For, as is perfectly clear in what precedes, at the time of Charles the boundaries of the kingdom of the Franks included the whole of Gaul and all Germany, from the Rhine to Illyricum. When the realm was divided between his son's sons, one part was called eastern, the other western, yet both together were called the Kingdom of the Franks. So then in the eastern part, which is called the Kingdom of the Germans, Henry was the first of the race of Saxons to succeed to the throne when the line of Charles failed ... [western Franks discussed] ... Henry's son Otto, because he restored to the German East Franks the empire which had been usurped by the Lombards, is called the first king of the Germans — not, perhaps, because he was the first king to reign among the Germans.[22]

It is here and elsewhere that Otto distinguishes the first German king (Henry I) and the first German king to hold imperial power (Otto I).[23]

Henry II (r. 1002-1024) was the first to be called "King of the Germans" (rex Teutonicorum).[24] The Ottonians seem to have adopted the use of the "Teutonic" label as it helped them to counter critics who questioned their political legitimacy as non-Carolingian Franks by presenting themselves as rulers of all peoples north of the Alps and east of the Rhine. This "German kingdom" was considered by them as a subdivision of the Empire alongside Italy, Burgundy and Bohemia.[25]

Salians and Staufer

In the late eleventh century the term "Kingdom of the Germans" (Regnum Teutonicorum) had become utilised more favourably in Germany due to a growing sense of national identity;[26] by the twelfth century, German historian Otto of Freising had to explain that East Francia was "now called the Kingdom of the Germans".[20]

In 1028, after his coronation as Emperor in 1027, Conrad II had his son, Henry III, elected King by the prince electors. When, in 1035, Conrad attempted to depose Adalbero, Duke of Carinthia, Henry, acting on the advice of his tutor, Egilbert, Bishop of Freising, refused to allow it, as Adalbero was a vassal of the King, not the Emperor. The German magnates, having legally elected Henry, would not recognise the deposition unless their king did also. After many angry protests, Conrad finally knelt before his son and pleaded for his desired consent, which was finally given.[27]

However, Conrad II used the simple title "king" or on occasion "king of the Franks and Lombards" before Imperial coronation, while his son Henry III introduced the title "King of the Romans" before the Imperial coronation.[28] His grandson Henry IV used both "king of the Franks and Lombards"[29] and King of the Romans before Imperial coronation.

Beginning in the late eleventh century, during the Investiture Controversy, the Papal curia began to use the term regnum teutonicorum to refer to the realm of Henry IV in an effort to reduce him to the level of the other kings of Europe, while he himself began to use the title rex Romanorum or King of the Romans to emphasise his divine right to the imperium Romanum. This title was employed most frequently by the German kings themselves, though they did deign to employ "Teutonic" titles when it was diplomatic, such as Frederick Barbarossa's letter to the Pope referring to his receiving the coronam Theutonici regni (crown of the German kingdom). Foreign kings and ecclesiastics continued to refer to the regnum Alemanniae and règne or royaume d'Allemagne. The terms imperium/imperator or empire/emperor were often employed for the German kingdom and its rulers, which indicates a recognition of their imperial stature but combined with "Teutonic" and "Alemannic" references a denial of their Romanitas and universal rule. The term regnum Germaniae begins to appear even in German sources at the beginning of the fourteenth century.[30]

When Pope Gregory VII started using the term Regnum Teutonicorum, the concept of a "distinct territorial kingdom" separate from Kingdom of Italy was already widely recognised on both sides of the Alps, and this entity was at least externally perceived as "German" in nature. Contemporary writers representing various German vassal rulers also adopted this terminology. In the Papal-Imperial Concordat of Worms of 1122, which put an end to the Investiture Controversy, the authority of the Emperor regarding Church offices in this "German kingdom" was legally distinguished from his authority in "other parts of the Empire". The Imperial chancery did adopt the "German" titles, albeit inconsistently.[31]

In the 13th century the term Regnum Teutonicorum started being replaced in Germany by the similar Regnum Alemanniae, possibly due to French or Papal influence, or alternatively due to the Staufer emperors' base of power in the Duchy of Swabia, also known as Alamannia. Emperor Frederick II even proclaimed his son Henry VII as Rex Alemannie (King of Germany), to rule Germany under him while he ruled the rest of the empire. The Kaiserchronik explicitly describes Henry as having rule of a separate German kingdom (siniu Tiuschen riche) under the empire. Henry's successor Konrad IV was also called king-designate of Germany by a contemporary writer.[31]

The Count Palatine of the Rhine was legally authorised to judge on the princes' affairs should the king leave Germany ("von teutchem lande"). In the Sachsenspiegel and Schwabenspiegel of the Medieval German law, the vassal princes were only required to provide service to the Empire and attend court within the German lands; Frederick II or his successors were unable to call upon the German lords to Bohemia, Italy or their other domains. Royal and Imperial legislation were sometimes specifically binding only within the borders of Germany, excluding the rest of the Empire.[32]

Post-Staufer period

German writers after the Staufen period used variants of the term "Regnum Alemanniae" to indicate the weakened reach of the emperors who now confined themselves mainly to German matters. Anti-king Henry Raspe also described himself as "king of Germany and prince of the Romans". There were also scattered references to a political community of "Germans" excluding the rest of the empire. For instance, in 1349, Charles IV met the nobles and burghers of "regnum Alamannie", in 1355 he summoned the electors and burghers "in regno Alemannie". However, this tendency to refer to a "German" polity after the collapse of the Staufen empire did not develop further in the following period.[8][31]

The term "regnum" was sometimes used to refer a distinct political entity within the "imperium", but sometimes they were used interchangeably, and sometimes they were combined in phrases like "Regnum Romanorum". In the German language it was most common to simply use the term "German lands" rather than "kingdom".[33] In 1349 Charles IV (King of the Romans) appointed the Duke of Brabant's son to govern on his behalf "in our kingdom of the Romans throughout Germania or Theutonia".[32]

There were persistent proposals, including one that Ptolemy of Lucca claimed was discussed between Pope Nicholas III and Rudolf I, to create a hereditary German kingdom independent from the Holy Empire. This idea was met with horror in Germany.[31] When Rudolf I was elected, the emotional attachment the German people had with the superior dignity of the universalistic Roman title had become so firmly established that it was unacceptable to separate the German kingship from it.[34] There was a strong reluctance by the Emperors to use "German" titles due to strong attachment to Roman symbolism, and it seemed to be actively avoided. References to "German" titles were less rare but still uncommon among vassals and chroniclers.[35]

From 1250 onward, the association between "Germans" and the whole Empire became stronger. As post-Staufer German monarchs were too weak to secure coronation as emperor, German writers became concerned that Germany was losing the prestige of Imperial status. The lack of concentration of power in one ruler or region also made the monarchy more attractive to all Germans. These led to more interest in connecting German identity to being heirs of Imperial Rome (Translatio Imperii), by right of their military strength as defenders of Christendom. At the same time, the replacement of Latin with German in official documents entrenched the German character of the empire at large. In 1474 the term "Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation" appeared, becoming more common after 1512. However, even after 1560, only 1 in 9 official documents mention "Germany", and most omitted the rest as well and simply called it "the Empire". In 1544 the Cosmographia (Sebastian Münster) was published, which used "Germany" (Teütschland) as synonymous with the empire as a whole. Johann Jacob Moser also used "German" as a synonym for "Imperial". This conflated definition of "German" even included non-German speakers.[36]

Ultimately, Maximilian I changed the style of the emperor in 1508, with papal approval: after his German coronation, his style was Dei gratia Romanorum imperator electus semper augustus. That is, he was "emperor elect": a term that did not imply that he was emperor-in-waiting or not yet fully emperor, but only that he was emperor by virtue of the election rather than papal coronation (by tradition, the style of rex Romanorum electus was retained between the election and the German coronation). At the same time, the custom of having the heir-apparent elected as king of the Romans in the emperor's lifetime resumed. For this reason, the title "king of the Romans" (rex Romanorum, sometimes "king of the Germans" or rex Teutonicorum) came to mean heir-apparent, the successor elected while the emperor was still alive.[37]

After the Imperial Reform and Reformation settlement, the German part of the Holy Roman Empire was divided into Reichskreise (Imperial Circles), which effectively defined Germany against imperial territories outside the Imperial Circles: imperial Italy, the Bohemian Kingdom, and the Old Swiss Confederacy.[38] Brendan Simms called the Imperial circles as "an embryonic German collective-security system" and "a potential vehicle for national unity against outsiders".[39]

Nevertheless, there are relatively few references to a German realm distinct from the Holy Roman Empire.[8]

See also

- King of the Romans

- List of German monarchs

- List of Holy Roman Emperors

Notes

- The Latin expression regnum Teutonicum corresponds to German-language deutsches Reich in literal translation; however, in German usage, the term deutsches Reich is reserved for the German national state of 1871–1945, see: Matthias Springer, "Italia docet: Bemerkungen zu den Wörtern francus, theodiscus und teutonicus" in: Dieter Hägermann, Wolfgang Haubrichs, Jörg Jarnut (eds.), Akkulturation: Probleme einer germanisch-romanischen Kultursynthese in Spätantike und frühem Mittelalter, Walter de Gruyter (2013), 68–98 (73f.).

- Len Scales (26 April 2012). The Shaping of German Identity: Authority and Crisis, 1245-1414. Cambridge University Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-521-57333-7. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "a conglomerate, an assemblage of a number of once separate and independent... gentes [peoples] and regna [kingdoms]." Gillingham (1991), p. 124, who also calls it "a single, indivisible political unit throughout the middle ages." He uses "medieval Germany" to mean the tenth to fifteenth centuries for the purposes of his paper. Robinson, "Pope Gregory", p. 729.

- Müller-Mertens 1999, p. 265.

- Robinson, "Pope Gregory", p. 729.

- Cristopher Cope, Phoenix Frustrated: the lost kingdom of Burgundy, p. 287

- Whaley, Germany and the Holy Roman Empire, pp. 20–22. The titles in Latin were sacri imperii per Italiam archicancellarius, sacri imperii per Germaniam archicancellarius and sacri imperii per Galliam et regnum Arelatense archicancellarius.

- Len Scales (26 April 2012). The Shaping of German Identity: Authority and Crisis, 1245-1414. Cambridge University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-521-57333-7. Retrieved 3 April 2013.

- Wilson, Peter, Heart of Europe (2016), p. 256

- Reynolds, Kingdoms and Communities, pp. 290–91.

- glossed as "more recent tribal duchies" in Patrick J. Geary, Phantoms of Remembrance: Memory and Oblivion at the End of the First Millennium (Princeont, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), p. 44.

- Herwig Wolfram, "The Shaping of the Early Medieval Principality as a Type of Non-royal Rulership", Viator, 2 (1971), p. 41.

- "The stem duchy did not arise out of the will of the leaderless stem but rather out of the duke's determination to rule. The duke himself was the political organization of the hitherto unorganized and leaderless stem." Gerd Tellenbach, Königtum und Stämme in der Werdezeit des Deutschen Reiches, Quellen und Studien zur Verfassungsgeschichte des Deutschen Reiches in Mittelalter und Neuzeit, vol. 7, pt. 4 (Weimar, 1939), p. 92, quoted and translated in Freed, "Reflections on the Medieval German Nobility", p. 555.

- This thesis was popularised for English scholars by Geoffrey Barraclough, The Origins of Modern Germany, 2nd ed. (New York: 1947).

- That he claimed the whole, and not just Bavaria, has been doubted by Geary, Phantoms of Remembrance, p. 44.

- James Westfall Thompson, "German Feudalism", The American Historical Review, 28, 3 (1923), p. 454.

- See Gillingham, Kingdom of Germany, p. 8 & Reindal, "Herzog Arnulf".

- Reynolds, Kingdoms and Communities, pp. 290-2; Beumann, "Die Bedeutung des Kaisertums", pp. 343-7.

- Avercorn, "Process of Nationbuilding", p. 186; Gillingham, Kingdom of Germany, p, 8; Reynolds, Kingdoms and Communities, p. 291.

- Len Scales (2012). The Shaping of German Identity: Authority and Crisis, 1245-1414. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 158–159.

- Reynolds, Kingdoms and Communities, pp. 289–98.

- Mierow, The Two Cities, pp. 376–7.

- See Otto's list of emperors, Mierow, The Two Cities, p. 451.

- Joachim Whaley (2018). "1". The Holy Roman Empire: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0191065641.

- Wilson, Peter, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire (2016), p. 257

- Heinrich August Winkler (2006). Germany: 1789-1933 Volume 1 of Germany: The Long Road West, Heinrich August Winkler. Oxford University Press. pp. 5–6. ISBN 0199265976.

- Wolfram, Herwig (2006). Conrad II, 990-1039: Emperor of Three Kingdoms. Translated by Kaiser, Denise A. Pennsylvania University Press. p. 86-87.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stefan Weinfurter (1999). The Salian Century: Main Currents in an Age of Transition. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0812235088.

- H. E. J. Cowdrey (1998). Pope Gregory VII, 1073-1085. Clarendon Press. p. 175. ISBN 0191584592.

- Averkorn 2001, p. 187.

- Len Scales (2012). The Shaping of German Identity: Authority and Crisis, 1245-1414. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 160-162, 165-169.

- Len Scales (2012). The Shaping of German Identity: Authority and Crisis, 1245-1414. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 185-188.

- Len Scales (2012). The Shaping of German Identity: Authority and Crisis, 1245-1414. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 180-182.

- James Vc Bryce (1863). The Holy Roman Empire by James Bryce. T. & G. Shrimpton, 1864. pp. 92–93.

- Len Scales (2012). The Shaping of German Identity: Authority and Crisis, 1245-1414. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 174-175.

- Wilson, Peter, Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire (2016), p. 255-259

- "the Holy Roman Empire".

- Bryce, p. 243

- Simms, Brendan (2013). Europe: The Struggle for Supremacy, 1453 to the Present. Penguin UK. p. 32. ISBN 1846147255.

Bibliography

- Arnold, Benjamin (1985). German Knighthood, 1050–1300. Oxford: Clarendon Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Benjamin (1991). Princes and Territories in Medieval Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Benjamin (1997). Medieval Germany, 500–1300: A Political Interpretation. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Arnold, Benjamin (2004). Power and Property in Medieval Germany: Economic and Social Change, c. 900–1300. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Averkorn, Raphaela (2001). "The Process of Nationbuilding in Medieval Germany: A Brief Overview". In Hálfdanarson, Gudmunður; Isaacs, Ann Katherine (eds.). Nations and Nationalities in Historical Perspective. University of Pisa.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barraclough, Geoffrey (1947). The Origins of Modern Germany (2nd ed.). Oxford: Basil Blackwell.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bernhardt, John W. (1993). Itinerant Kingship and Royal Monasteries in Early Medieval Germany, c. 936–1075. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beumann, H., "Die Bedeutung des Kaisertums für die Entstehung der deutschen Nation im Spiegel der Bezeichnungen von Reich und Herrscher", in Nationes, 1 (1978), pp 317–366

- Viscount James Bryce. The Holy Roman Empire.

- Du Boulay, F. R. H. (1983). Germany in the Later Middle Ages. New York: St Martin's Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fuhrmann, Horst (1986). Germany in the High Middle Ages, c.1050–1200. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fuhrmann, Horst (1994). "Quis Teutonicos constituit iudices nationum? The Trouble with Henry". Speculum. 69 (2): 344–58. doi:10.2307/2865086.

- Gagliardo, John G. (1980). Reich and Nation: The Holy Roman Empire as Idea and Reality, 1763–1806. University of Indiana Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gillingham, John (1971). The Kingdom of Germany in the High Middle Ages (900–1200). Historical Association Pamphlets, General Series, No. 77. London: Historical Association.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gillingham, John (1991). "Elective Kingship and the Unity of Medieval Germany". German History. 9 (2): 124–35. doi:10.1177/026635549100900202.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hampe, Karl (1973). Germany under the Salian and Hohenstaufen Emperors. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Haverkamp, Alfred (1992). Medieval Germany, 1056–1273 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Heer, Friedrich (1968). The Holy Roman Empire. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Leyser, Karl J. (1979). Rule and Conflict in an Early Medieval Society : Ottonian Saxony. London: Arnold.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lyon, Jonathan R. (2013). Princely Brothers and Sisters: The Sibling Bond in German Politics, 1100–1250. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, Otis C. (1985). Two German Crowns: Monarchy and Empire in Medieval Germany. Lima, OH: Wyndham Hall Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Müller-Mertens, Eckhard (1970). Regnum Teutonicum: Aufkommen und Verbreitung der deutschen Reichs- und Königsauffassung im früheren Mittelalter. Hermann Böhlaus.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Müller-Mertens, Eckhard (1999). "The Ottonians as Kings and Emperors". In Reuter, Timothy (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 3: c.900 – c.1024. Cambridge University Press. pp. 233–66.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Osiander, Andreas (2007). Before the State: Systemic Political Change in the West from the Greeks to the French Revolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reindal, R. (1954). "Herzog Arnulf und das Regnum Bavariae". Zeitschrift für bayerische Landesgeschichte. 17: 187–252.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reuter, Timothy (1991). Germany in the Early Middle Ages, c. 800–1056. London: Longman.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reynolds, Susan (1997). Kingdoms and Communities in Western Europe, 900–1300 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Ian S. (1979). "Pope Gregory VII, the Princes and the Pactum, 1077–1080". The English Historical Review. 94 (373): 721–56. doi:10.1093/ehr/xciv.ccclxxiii.721.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Ian S. (2000). Henry IV of Germany. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Thompson, James Westfall (1928). Feudal Germany. 2 vols. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Whaley, Joachim (2012). Germany and the Holy Roman Empire. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Peter (2016). Heart of Europe: A History of the Holy Roman Empire. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)