Bohemian Revolt

The Bohemian Revolt (German: Böhmischer Aufstand; Czech: České stavovské povstání; 1618–1620) was an uprising of the Bohemian estates against the rule of the Habsburg dynasty that began the Thirty Years' War. It was caused by both religious and power disputes. The estates were almost entirely Protestant, mostly Utraquist Hussite but there was also a substantial German population that endorsed Lutheranism. The dispute culminated after several battles in the final Battle of White Mountain, where the estates suffered a decisive defeat. This started re-Catholisation of the Czech lands, but also expanded the scope of the Thirty Years' War by drawing Denmark and Sweden into it. The conflict spread to the rest of Europe and devastated vast areas of central Europe, including the Czech lands, which were particularly stricken by its violent atrocities.

| Bohemian Revolt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Thirty Years' War | |||||||

The Second Defenestration of Prague | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Rebellion

Without heirs, Emperor Matthias sought to assure an orderly transition during his lifetime by having his dynastic heir (the fiercely Catholic Ferdinand of Styria, later Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor) elected to the separate royal thrones of Bohemia and Hungary.[1] Some of the Protestant leaders of Bohemia feared they would be losing the religious rights granted to them by Emperor Rudolf II in his Letter of Majesty (1609). They preferred the Protestant Frederick V, elector of the Palatinate (successor of Frederick IV, the creator of the Protestant Union). However, other Protestants supported the stance taken by the Catholics, and in 1617, Ferdinand was duly elected by the Bohemian Estates to become the Crown Prince, and automatically upon the death of Matthias, the next King of Bohemia.

The king-elect then sent two Catholic councillors (Vilem Slavata of Chlum and Jaroslav Bořita of Martinice) as his representatives to Prague Castle in May 1618. Ferdinand had wanted them to administer the government in his absence. On 23 May, an assembly of Protestants seized them and threw them (and also secretary Philip Fabricius) out of the palace window, which was some 17 metres (56 ft) off the ground. Remarkably, although injured, they survived. This event, known as the (Second) Defenestration of Prague, started the Bohemian Revolt. Soon afterward, the Bohemian conflict spread through all of the Bohemian Crown, including Bohemia, Silesia, Upper and Lower Lusatia, and Moravia. Moravia was already embroiled in a conflict between Catholics and Protestants. The religious conflict eventually spread across the whole continent of Europe, involving France, Sweden, and a number of other countries.

Had the Bohemian rebellion remained a local conflict, the war could have been over in fewer than thirty months. However, the death of Emperor Matthias emboldened the rebellious Protestant leaders, who had been on the verge of a settlement. The weaknesses of both Ferdinand (now officially on the throne after the death of Emperor Matthias) and of the Bohemians themselves led to the spread of the war to western Germany. Ferdinand was compelled to call on his cousin, King Philip III of Spain, for assistance. The Spanish Crown had interests in maintaining the Holy Roman Empire as a stable ally; a critical trade route, the "Spanish Road", extended from the Mediterranean to Brussels. To this end they invested an enormous sum of treasure in the hiring of free companies and mercenaries.

The Bohemians, desperate for allies against the Emperor, applied to be admitted into the Protestant Union, which was led by their original candidate for the Bohemian throne, the Calvinist Frederick V, Elector Palatine. The Bohemians hinted Frederick would become King of Bohemia if he allowed them to join the Union and come under its protection. However, similar offers were made by other members of the Bohemian Estates to the Duke of Savoy, the Elector of Saxony, and the Prince of Transylvania. The Austrians, who seemed to have intercepted every letter leaving Prague, made these duplicities public.[2] This unraveled much of the support for the Bohemians, particularly in the court of Saxony. Even James I of England refused to support Frederick, despite his wife being James' daughter. Overall, England was criticized for its inaction in the Thirty Years' War. In spite of these issues surrounding their support, the rebellion initially favoured the Bohemians. They were joined in the revolt by much of Upper Austria, whose nobility was then chiefly Lutheran and Calvinist. Lower Austria revolted soon after, and in 1619, Count Thurn led an army to the walls of Vienna itself.

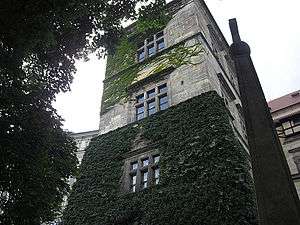

The window (second floor) where the Second Defenestration occurred. Note the monument to the right of the castle tower.

The window (second floor) where the Second Defenestration occurred. Note the monument to the right of the castle tower. Historical re-enactment of the Battle of White Mountain

Historical re-enactment of the Battle of White Mountain

Defeat of the revolt

The Spanish sent an army from Brussels under Ambrosio Spinola to support the Emperor. In addition, the Spanish ambassador to Vienna, Don Íñigo Vélez de Oñate, persuaded Protestant Saxony to intervene against Bohemia in exchange for control over Lusatia, in addition they would invest nearly two million ducats in the supply and payment of both the army and its free company contingents. The Saxons invaded, and the Spanish army in the west prevented the Protestant Union's forces from assisting. Oñate conspired to transfer the electoral title from the Palatinate to the Duke of Bavaria in exchange for his support and that of the Catholic League.

The Catholic League's army (which included René Descartes in its ranks as an observer) pacified Upper Austria, while Imperial forces under Johan Tzerclaes, Count of Tilly, pacified Lower Austria. The two armies united and moved north into Bohemia. Ferdinand II decisively defeated Frederick V at the Battle of White Mountain, near Prague, on 8 November 1620. In addition to becoming almost entirely Catholic, Bohemia would remain in Habsburg hands for nearly three hundred years.

This defeat led to the dissolution of the League of Evangelical Union and the loss of Frederick V's holdings. Frederick was outlawed from the Holy Roman Empire, and his territories, the Rhenish Palatinate, were given to Catholic nobles. His title of elector of the Palatinate was given to his distant cousin, Duke Maximilian of Bavaria. Frederick, now landless, made himself a prominent exile abroad and tried to curry support for his cause in Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark.

This was a serious blow to Protestant ambitions in the region. As the rebellion collapsed, the widespread confiscation of property and suppression of the Bohemian nobility ensured the country would return to the Catholic side after more than two centuries of Hussite and other religious dissent. However while Bohemia was effectively annexed by the Crown, other regions would continue their revolt for several years. This would have the effect of bringing in elements of the Protestant Union which had suffered a severe blow to their credibility via their refusal to support the Bohemian revolutionaries. In addition, the changes in territory meant that previously unaligned powers would find a resurgent Empire on their own borders, a circumstance that Kingdoms like Denmark found untenable.

See also

References

- "The Defenestration of Prague « Criticality". steveedney.wordpress.com. Retrieved 25 May 2008.

- T. Walter Wallbank; Alastair M. Taylor; Nels M. Bailkey; George F. Jewsbury; Clyde J. Lewis; Neil J. Hackett (1992). "15. The Development of the European State System: 1300–1650". In Bruce Borland (ed.). Civilization Past & Present Volume II. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 0-673-38869-7. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 23 May 2008.