Religion in the Czech Republic

Religion in the Czech Republic was dominated by Christianity until at least the early 20th century, but today Czechia is characterised as being one of the least religious societies in the World.[2] Since the 1620 Battle of White Mountain religious sphere was accompanied by a widespread anti-Catholic sentiment even when the whole population nominally belonged to the Catholic Church. Overall, Christianity has steadily declined since the early 20th century and today remains only a minority. The Czech Republic has one of the oldest least religious populations in the world. Ever since the 1620 Battle of White Mountain, the Czech people have been historically characterised as "tolerant and even indifferent towards religion".[3] According to Jan Spousta, among the irreligious people, who form the vast majority of modern Czechs, not all are atheists; indeed there has been an increasing distancing from both Christian dogmatism and atheism, and at the same time ideas from Far Eastern religions have become widespread.[4]

Religion in the Czech Republic (2011)[1]

Christianisation in the 9th and 10th centuries introduced Roman Catholicism. After the Bohemian Reformation, most Czechs (about 85%) became followers of Jan Hus, Petr Chelčický and other regional Protestant Reformers. Taborites and Utraquists were major Hussite groups. During the Hussite Wars, Utraquists sided with the Catholic Church. Following the joint Utraquist—Catholic victory, Utraquism was accepted as a distinct form of Christianity to be practised in Bohemia by the Catholic Church while all remaining Hussite groups were prohibited. After the Reformation, some Bohemians went with the teachings of Martin Luther, especially Sudeten Germans. In the wake of the Reformation, Utraquist Hussites took a renewed increasingly anti-Catholic stance, while some of the defeated Hussite factions (notably Taborites) were revived. Bohemian Estates' defeat in the Battle of White Mountain brought radical religious changes and started a series of intense actions taken by the Habsburgs in order to bring the Czech population back to the Catholic Church. After the Habsburgs regained control of Bohemia, the whole population was forcibly converted to Roman Catholicism—even the Utraquist Hussites. All kinds of Protestant communities including the various branches of Hussites, Lutherans and Reformed were either expelled, killed, or converted to Roman Catholicism. Going forward, Czechs have become more wary and pessimistic of religion as such. A long history of resistance to the Catholic Church followed. It suffered a schism with the neo-Hussite Czechoslovak Hussite Church in 1920, lost the bulk of its adherents during the communist era and continues to lose in the modern, ongoing secularisation. Protestantism never recovered after the Counter-Reformation was introduced by the Austrian Habsburgs in 1620.

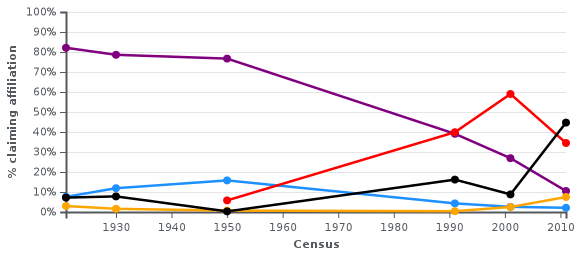

From 1991 to 2001 the population's proportion of members of the Roman Catholic Church decreased from 39.0% to 26.8%. Protestantism declined from 4% to 2%. According to the 2011 census, due to changes in the question categories, each category has seen a decrease: the proportion of people who have no religion declined from 59% to 34.5%, the Catholics declined from 26.8% to 10.5% and Protestants declined from 2% to 1%, 0.9% members of other Christian churches, 6.8% were believers but not members of religions, while 0.7% were believers and members of other certain religions. People who didn't answer the optional question rose from 8.8% to 44.7%.[1]

Statistics

Census results

| Religion | 1921 | 1930 | 1950 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Christianity | 8,974,423 | 89.7 | 9,668,948 | 90.5 | 8,287,957 | 93.1 | 4,486,296 | 43.5 | 3,028,941 | 29.5 | 1,317,087 | 12.6 |

| —Roman Catholic Church | 8,201,464 | 82.0 | 8,378,079 | 78.5 | 6,792,046 | 76.3 | 4,021,385 | 39.0 | 2,740,780 | 26.8 | 1,082,463 | 10.4 |

| ——Ruthenian Greek Catholic Church | 9,307 | 0.1 | 12,149 | 0.1 | 32,862 | 0.4 | 7,030 | 0.1 | 7,675 | 0.1 | 9,883 | 0.1 |

| —Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren | 231,199 | 2.3 | 290,994 | 2.7 | 401,729 | 4.5 | 203,996 | 2.0 | 117,212 | 1.1 | 51,858 | 0.5 |

| —Czechoslovak Hussite Church | 523,232 | 5.2 | 779,672 | 7.3 | 946,813 | 10.6 | 178,036 | 1.7 | 99,103 | 1.0 | 39,229 | 0.4 |

| —Silesian Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession | - | - | 46,777 | 0.4 | 57,741 | 0.6 | 33,130 | 0.3 | 14,020 | 0.1 | 8,158 | 0.1 |

| —German Evangelical Church in Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia | - | - | 130,981 | 1.2 | 6,401 | 0.1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| —Czech and Slovak Orthodox Church | 9,221 | 0.1 | 24,488 | 0.2 | 50,365 | 0.6 | 19,354 | 0.2 | 22,968 | 0.2 | 20,533 | 0.2 |

| —Jehovah's Witnesses | - | - | - | - | - | - | 14,575 | 0.1 | 23,162 | 0.2 | 13,069 | 0.1 |

| —Christian churches not exactly stated | - | - | 5,808 | 0.1 | - | - | 8,790 | 0.1 | 4,021 | 0.04 | 91,894 | 0.8 |

| Judaism | 125,083 | 1.3 | 117,551 | 1.1 | 8,038 | 0.1 | 1,292 | 0.01 | 1,515 | 0.01 | 1,474 | 0.01 |

| Believers identified with another certain religion | 168,046 | 1.7 | 53,743 | 0.5 | 57,287 | 0.6 | 36,146 | 0.4 | 257,641 | 2.5 | 75,190 | 0.7 |

| Believers not identified with a certain religion | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 705,368 | 6.8 |

| No religion | 716,515 | 7.2 | 834,144 | 7.8 | 519,962 | 5.8 | 4,112,864 | 39.9 | 6,039,991 | 59.0 | 3,604,095 | 34.5 |

| Not stated | 1,564 | 0.01 | 22,889 | 0.3 | 1,665,617 | 16.2 | 901,981 | 8.8 | 4,662,455 | 44.7 | ||

| Total population | 10,005,734 | 10,674,386 | 8,896,133 | 10,302,215 | 10,230,060 | 10,436,560 | ||||||

Other surveys

- The Eurobarometer Poll 2010 found that 16% of Czech citizens responded that "they believe there is a God", 44% responded that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" and 37% responded that "they don't believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force". 3% gave no response.[5]

- Eurobarometer found in 2015 that 38.6% of Czech citizens declared to be agnostics/irreligious.[6] Christianity accounted for 31.5% of Czech citizens. Roman Catholics were the largest Christian denomination, making up 27.1% of Czech citizens, while Protestants made up 1.0%, and other types of Christians were 3.4%. Atheists accounted for 25.8% of the population.[6]

- Pew Research Center found in 2015 that 72% of the population of Czech Republic declared to be irreligious—a category which includes atheists, agnostics and those who describe their religion as "nothing in particular"—, 26% were Christians, while 2% belonged to other faiths.[7] The Christians were divided between a 21% who were Roman Catholic, 4% other Christians and 1% who were Eastern Orthodox.[7] While unaffiliated people were divided between a 25% who were atheists, 1% agnostics and 46% who declare to believe to "nothing in particular". Also, 29% said that they believe in God, 43% had a belief in fate and 44% believed in the existence of the soul.[8]

Religions

Christianity

Christianity was the largest religion in the country, with virtually all Czechs being Christians until the 19th century. The Czechs gradually converted to Christianity from Slavic paganism between the 8th and the 10th century. Bořivoj I, Duke of Bohemia, baptised by the Saints Cyril and Methodius, was the first ruler of Bohemia to adopt Christianity as the state religion. Christianity has been on the decline since the 20th century and in 2011 only 12.6% of the Czechs declared to be Christians, of whom 10.5% were Catholics, 1% Protestants and 1.1% members of other Christian bodies.[1] In 1921, 77.5% of the Czech population was Roman Catholic, 7.7% belonged to the Czechoslovak Hussite Church that broke off the Catholic Church in 1920, 3.4% belonged to the Czech Brethren, 0.3% were other Protestants, 0.7% were religious Jews, 0.1% belonged to some other religious category, and a further 10.3% were irreligious.[9]

Roman Catholicism

The Catholic Church was the main form of Christianity historically practised by the Czechs, after their forced conversion under the Habsburgs, and throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Roman Catholicism was still the professed religion of 96.5% of the Czechs in 1910. A decline in the number of Czech Catholics began after World War I and the breakup of Austria-Hungary due to a popular anti-Austrian and anticlerical mass movement.[10] During the Czechoslovak unification under a communist regime, most of the properties of the Church were confiscated by the government, although some were later returned. After the communist regime fell, 39.0% of Czechs were found to be Catholic in 1991, but the faith has continued to rapidly decline since. As of 2011 only 10.5% of the Czechs considered themselves Roman Catholic, which is about the same as in Protestant-majority England.

The rapid trend away from Catholic identification and toward irreligion in the Czech Republic stands in stark contrast to the situation in neighboring Poland or Slovakia.

Protestantism

In the 15th century, the religious and social reformer Jan Hus formed a movement later named after him. Although Hus was named a heretic and burnt in Constance in 1415, his followers seceded from the Roman Catholic Church and in the Hussite Wars (1419–1434) defeated five crusades organised against them by the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund. Petr Chelčický continued with the Czech Hussite Reformation movement. During the next two centuries, most of Czechs were adherents of Hussitism.

After 1526 Bohemia came increasingly under Habsburg control as the Habsburgs became first the elected and then the hereditary rulers of Bohemia. The Defenestration of Prague and subsequent revolt against the Habsburgs in 1618 marked the start of the Thirty Years' War, which quickly spread throughout Central Europe. In 1620, the rebellion in Bohemia was crushed at the Battle of White Mountain, and the ties between Bohemia and the Habsburgs' hereditary lands in Austria were strengthened. The war had a devastating effect on the local population; the people were forced to convert to Roman Catholicism.

Protestantism constitutes a 1% small minority in the country in the 2010s, with only 0.5% of the Czechs adhering to the Evangelical Church of Czech Brethren, 0.4% to the Czechoslovak Hussite Church, and 0.1% to the Silesian Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession.[1] The Moravian Church, being historically tied to the region, is present too with a small number of members.

Buddhism

The 2001 census counted 6,817 registered Buddhists in the Czech republic.[1] Most of the Vietnamese ethnic minority, which make up the largest immigrant ethnic group in the country, are adherents of Mahayana Buddhism. The Vietnamese mostly dwell in the cities of Prague and Cheb. Thein An Buddhist Temple in the northern province of Varnsdorf was the first Vietnamese-style temple to be consecrated in the Czech Republic, in January 2008. There are also ten Korean Buddhist temples in the Czech Republic, with three each in Prague and Brno.[11]

Ethnic Czech Buddhists are otherwise mostly followers of Vajrayana Buddhism (Tibetan Buddhism). The Vajrayana practitioners are mainly centered on the Nyingma and Kagyu schools. The Karma Kagyu tradition has established about 50 centers and meditation groups. The Diamond Way tradition of Vajrayana Buddhism, founded and directed by Ole Nydahl is active in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia. A large temple of the school is going to be built in the city of Prague.[12]

Irreligion

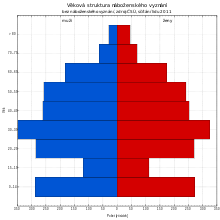

The Czech Republic is one of the least religious countries in the world. Vera Haberlová of STEM, for example, writes about 50% representation of atheists in Czech society. In doing so, however, it comes from simple inquiries to the question "Do you believe in God?", which also indicates a very simplistic evaluation, because a high percentage of respondents classified this way that also believe in some other "Higher Power."[15] Summary group of non-believers in God was, According to STEM survey in June 1996 Represented 48.8% of the Czech population and in July 1998 it was 47.6%. In 1994 According to STEM called themselves atheists are 21.5% of persons aged 18 years and 20.3% of those aged 15–17 years, while a further 38.2%, respectively.[15] 40.8% of people said they are not religious.[15]

According to the results of the 2001 census 7% more men were without religion than women. The age group most likely to have no religion (74%) is young people 0–30 years old, the least likely (28%) is people aged 60+ years. When categorised by education, the higher the educational level achieved, the more people were to state they had no religion.

There is an organised group of atheists in the Czech Republic, the Civic Association of Atheists, a member of the international organisation of atheists Atheist Alliance International (AAI). Not all irreligious Czechs are atheists; a number of non-religious people have adopted ideas from Far Eastern religions.[4]

References

- Official census data from the Czech Statistical Office:

- "Obyvatelstvo podle náboženského vyznání a pohlaví podle výsledků sčítání lidu v letech 1921, 1930, 1950, 1991 a 2001" [Population by denomination and sex: as measured by 1921, 1930, 1950, 1991 and 2001 censuses] (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2011.

- "Obyvatelstvo podle náboženské víry a pohlaví podle výsledků sčítání lidu v letech 1921, 1930, 1950, 1991, 2001 a 2011" [Population by religious belief and sex by 1921, 1930, 1950, 1991, 2001 and 2011 censuses].

- "2011 Census: Population by religious belief and by regions" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 November 2013.

- "2011 Census: Population by religious belief and by municipality size groups" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 February 2015.

- Hamplová, Done (2010). "Are Czechs the least religious of all?". The Guardian.

- Richard Felix Staar, Communist regimes in Eastern Europe, Issue 269, p. 90

- Spousta, Jan (2002). "Changes in Religious Values in the Czech Republic" (PDF). Czech Sociological Review. 38 (3). pp. 345–363.

- "Eurobarometer on Biotechnology 2010 – page 381" (PDF). Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- "DISCRIMINATION IN THE EU IN 2015", Special Eurobarometer, 437, European Union: European Commission, 2015, retrieved 15 October 2017 – via GESIS

- ANALYSIS (10 May 2017). "Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Religious Belief and National Belonging in Central and Eastern Europe: 1. Religious affiliation; Pew Research Center, 10 May 2017

- Grundriss der Statistik. II. Gesellschaftsstatistik by Wilhelm Winkler, p. 36

- Wolfram Kaiser; Helmut Wohnout (2004). Political Catholicism in Europe 1918-1945. Taylor & Francis. pp. 181–2. ISBN 978-0-203-64246-7.

- Korean Buddhist congregations in the Czech Republic, Buddha Dharma Education Association, 2006, retrieved 2010-05-01

- S.Parker (12 January 2013). "West Wight Sangha - Biggest Czech Buddhist Centre Being Built in Prague". west-wight-sangha.blogspot.it. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- Kaarina Aitamurto, Scott Simpson. Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Part II, 11: Neo-Paganism in the Czech Republic, Anna-Marie Dostalova. 2013. ISBN 1844656624

- Ryan Scott. Pagans help ring in the spring - Seasonal 'Beltane' rituals flourish in the Czech Republic. The Prague Post, 2011.

- "Problémy empirického zkoumání religiozity v české společnosti". Stem.cz. 2003-02-04. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

Further reading

- Vogel, Jiří (2017). "THE DECLINE OF CHURCHES IN THE CZECH REPUBLIC AND THE QUESTION OF SOCIAL IDENTITY". Danubius. XXXV: 437‐454.