The Ruin (Ukrainian history)

The Ruin (Ukrainian: Руїна, romanized: Ruyína) is a historical term introduced by the Cossack chronicle writer Samiylo Velychko (1670–1728) for the political situation in Ukrainian history during the second half of the 17th century.

| The Ruin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

Right-bank Ukraine |

Ottoman Ukraine (from 1669) |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

Ottoman Hetmans

| ||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Ukraine |

|

|

Early history

|

|

Modern history

|

|

Topics by history |

|

|

The timeframe of the period varies among historians:

- Some historians such as Nikolay Kostomarov define the period between 1663 and 1687, associating it with the three Moscow-appointed hetmans of the Left-bank Ukraine (Briukhovetsky, Mnohohrishny and Samoylovych).

- Other historians interpret the period between 1660 and 1687 from the Chudniv Treaty that led to division among the Cossack community.

- Borys Krupnytsky considered the timeframe as 1657–1687, from the death of hetman Bohdan Khmelnitsky in 1657, particularly the Pushkar-Barabash Mutiny, until the ascension of hetman Ivan Mazepa in 1687.

The period was characterised by continuous strife, civil war, and foreign intervention by neighbours of Ukraine. A Ukrainian saying of the time, "Від Богдана до Івана не було гетьмана" (From Bohdan to Ivan there was no hetman [in between]), accurately summarises the chaotic events of this period.

Background

The Ruin started after the death of hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky in 1657. Khmelnytsky had delivered Ukraine from centuries of Polish and Lithuanian domination through the campaigns of the Khmelnitsky Uprising (1648–1657) and Ukraine's Treaty of Pereyaslav (1654) with the Tsardom of Moscow. While Khmelnytsky had operated as a charismatic and influential leader, clearly one of the prominent figures in Ukrainian history, he did not establish clear rules of succession and his will favoured his son Yurii as the new hetman. Yurii Khmelnytsky (1641–1685), young and inexperienced, clearly lacked the charisma and the leadership qualities of his father, as he showed during his attempts to rule (1657, 1659–1663, 1677–1681, 1685).

At the time of Bohdan Khmelnytsky's death, the Cossack state had a territory of about 250,000 square miles (650,000 km2) and a population of around 1.2 to 1.5 million. Society consisted of the remaining non-Catholic nobles, the starshina or richer Cossack officers, the mass of the Cossacks and those peasants who did not bear arms. The Orthodox Church held 17% of the land; local nobles held 33%. The remaining 50% had been confiscated from the Poles and was up for grabs. Ukrainians comprised a frontier society with no natural borders, no tradition of statehood and a population committed to Cossack liberty or anarchy.

The confiscated lands could easily change hands in any conflict. There was an unresolved conflict between the mass of poorer cossacks and the wealthier group who aspired to semi-noble status. The state was weak and needed a protector, but of the regional powers, the Poles wanted to take the Ukrainian lands back, Muscovite-Russian autocracy fitted ill with Cossack ideals of liberty, the Crimean Khanate concentrated on Slavic slave-raiding and the Turks of the Ottoman Empire showed little concern for the Ukrainian frontier. The Swedish Empire's territory remained still too far away during this period, and the Don Cossacks and the Kalmucks stayed out of the conflict.

The history of Ukraine in this period became very complex. Basic themes included:

- the failure to find a single leader of Ukraine who could pursue a consistent policy

- the constant switching of alliances with outside powers who had their own interests

- the conflict between the richer and poorer Cossacks

- the influence of the Orthodox Church, which tended to favour coreligionist Moscow

Left and Right Banks 1648–1663

1648-57: Khmelnitsky: Crimea and Russia: Khmelnitsky started his rebellion in alliance with the Khanate of Crimea. When his acceptance of Russian overlordship in 1654 (Treaty of Pereiaslav) led to the Russo-Polish War (1654–1667), the Crimeans switched sides and began raiding Ukraine. In his last years Khmelnitsky backed away from Russia and was negotiating with Sweden and Transylvania.

1657-59: Vyhovsky and the Poles: At the time of Khmelnitsy's death his son Yurii was only 16, so the hetmanate was given to Ivan Vyhovsky (regent). He based his power on the richer cossacks ('starshina') and sought a rapprochement with Poland. This led to a rebellion of the more democratic cossacks Martyn Pushkar and Yakiv Barabash, which was defeated in June 1658, a civil war that cost about 50,000 lives. In September 1658 he signed the Treaty of Hadiach with Poland, which would have turned Ukraine into a third member of the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth, but the treaty was never implemented. The treaty led to a massive Russian invasion that was defeated at the Battle of Konotop on 29 June 1659. Faced with a revolt by several pro-Moscow colonels, Vyhovsky resigned and retired to Poland in October 1659.

1659-63: Yurii Khmelnitsky: Russia and Poland: The hetmanate passed to Bohdan's son Yurii Khmelnytsky who was now about 18. In 1659 he was forced to sign the Pereiaslav Articles, which were often confused with the treaty itself. They significantly increased Russian power. The next year, fighting resumed between Russia and Poland. Yurii hung back. After a number of Polish victories, Yurii agreed to return Ukraine to the commonwealth. This led the right-bank cossacks under Yakym Somko to depose him. Depressed by this effective partition of Ukraine, in January 1663 Yurii surrendered his hetman's mace and retired to a monastery.

Polish Right Bank 1663–1681

1663-65: Teteria and Poland: Pavlo Teteria, who held only the right bank, followed a strongly pro-Polish policy. When his invasion of the left bank failed, he returned to deal with the numerous rebellions that had broken out against the Poles. The behaviour of his Polish allies cost him what little support he had, and he resigned and fled to Poland.

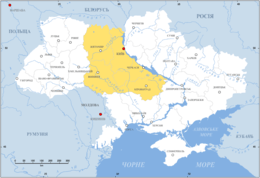

1665-76: Doroshenko and the Turks: The goal of Petro Doroshenko was to re-unite the two halves of Ukraine. He held frequent councils to cultivate the poorer cossacks and created a 20,000 man band of mercenaries to free himself from the starshina. In 1667, Russia and Poland, without consulting the cossacks, signed the Treaty of Andrusovo, which partitioned the cossack lands at the Dnieper river. The thinly populated southern area (Zaporozhia) was to be a Russo-Polish condominium, but it was in practice self-governing to the extent that it had a government. In response, Doroshenko turned to the Turks (Polish-Cossack-Tatar War (1666–1671)). In the fall of 1667 an Ottoman-Cossack force invaded Galicia and compelled the king to grant extensive autonomy to Doroshenko. He accepted a loose Ottoman overlordship, invaded the left bank, removed the rival hetman and in 1668 declared himself hetman of a united Ukraine. Crimea backed a rival hetman and the Poles backed Mykhailo Khanenko, with whom they invaded the right bank. Turning to meet the invaders, he placed Demian Mnohohrishny in control of the left bank, which quickly came under Russian control. In 1672 he helped the Turks annex Podolia. During the Russo-Turkish War (1676–1681) he aided the Turks against Russia. This involvement with non-Christians cost him his remaining support. On 19 September 1676, he gave up authority to Ivan Samoylovych of the left bank and went into exile in Russia.

1678-81: Yurii Khmelnitsky and the Turks: In 1678 the Turks, who had a large army in the area, appointed their prisoner Yurii Khmelnytsky as hetman. He participated in the second campaign of Chyhyryn and was deposed by the Turks in 1681.

At this point, English sources become thin. The Right Bank was severely depopulated, many of those who were not killed or enslaved by the Tatars having fled to the Left Bank or Sloboda Ukraine. Polish rule was gradually restored and the country began to fill up again.

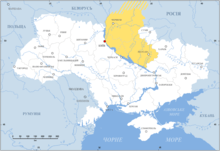

Russian Left Bank 1661–1687

1661-63: Somko and the Starshina: In 1660 the left bank cossacks deposed Yurii Khmelnitsky because of the Polish alliance and made Yakym Somko Acting Hetman. Yurii held on to the right bank, effectively partitioning the country. Somko favored the upper class provoking the opposition of the Zaporozhians under Bruikhevetsky. He also lost the support of Moscow. At the Chorna rada of 1663, he was replaced by Briukhovetsky and executed.

1663-68: Briukhovetsky and the Russians 1663–1668: Ivan Briukhovetsky was almost completely dependent on Russia. In 1665 he went to Moscow and signed the Moscow Articles of 1665. Russian tax collectors and soldiers were allowed in, a Russian was to be head of the church, a Russian representative was to be present at hetman elections and the Hetman was to go to Moscow for confirmation. Soldiers and tax collectors provoked resistance and the church resisted Muscovite influence. The Truce of Andrusovo (1667) seemed a Russian betrayal of cossack interests. A series of revolts broke out. Bruikovetsky back pedaled. In the spring of 1668, as Doroshenko's forces crossed the Dnieper, Bruikovetsky was beaten to death by a mob.

1668-72: Mnohohrishny and Left Bank Autonomy: On 9 June 1668 Doroshenko proclaimed himself hetman of a united Ukraine. In 1669 the Poles set up a rival hetman, Mykhailo Khanenko, and invaded the right bank. Turning to meet the invasion, Doroshenko placed Demian Mnohohrishny as acting hetman of the left bank. As Doroshenko weakened, and under Russian pressure, he accepted Russian supremacy. A stable relationship developed as Moscow moderated its demands and Mnohohrisny protected local interests. He made some progress in restoring law and order but could not control the starshina. Some of these denounced him to the Czar, who had him arrested, tortured and exiled to Siberia.

1672-87: Samoylovych and Russia: When Ivan Samoylovych was elected hetman he agreed to limited powers. He could not judge the starshina or carry on foreign relations without the consent of the starshina council. He disbanded the hired troops under the hetman's direct control. In 1674 and 1676 he and his Russian ally besieged Doroshenko at Chyhyryn. On September 19, 1676, Doroshenko surrendered to Samylovych, who declared himself hetman of a united Ukraine. But within two years the Turks drove him back across the Dnieper. Poland and Russia signed the Eternal Peace Treaty of 1686, which again recognized Polish rule of the right bank and removed the Poles from Zaporozhia, a major disappointment for Samoylovych. In 1687, 100,000 Russians and 50,000 Cossacks launched an attack on the Crimea (Crimean campaigns), which failed. Samoylovych was blamed, removed, and exiled to Siberia.

1687–1709: Mazepa and Stability: With the election of Ivan Mazepa as hetman, the Ruin effectively came to an end, and the history of the left bank merged with the Hetmanate as part of Russia. With the start of the Great Northern War in 1700, Russian demands began to seem excessive. In 1708 Mazepa allied himself with Charles XII of Sweden. At the Battle of Poltava, Charles, Mazepa and those cossacks that followed him were defeated and exiled to Turkey.

Results

- The attempt to create a Ruthenian Cossack state failed.

- Ukraine was partitioned between Russia and Poland along the Dnieper.

- Poland lost the left bank, became weakened and declined.

- Russia expanded to the south and somewhat to the southwest.

- There was a major shift of Ruthenian population from the devastated right bank to the left bank and Sloboda Ukraine, thereby increasing the area under peasant agriculture.

- Turkey briefly expanded its power into Ukraine (Doroshenko to about 1699).

List of Treaties

For reference, this is a list of treaties and agreements during the period.

- 1648: Cossacks ally with Crimea.

- 1648: Truce of Zamość: short-lived compromise

- 1649: Treaty of Zboriv: 40000 Registered Cossacks; no Polish soldiers or Jews in central Ukraine; not implemented

- 1651: Treaty of Bila Tserkva: 20000 Registered Cossacks; Jews and nobles to return; partly implemented

- 1654: Treaty of Pereyaslav: Cossack alliance with Russia; provokes Russo-Polish War (1654–1667).

- 1658: Treaty of Hadiach: Rejects 1654; Ukraine a third member of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth; 30000 registered Cossacks; never implemented.

- 1659: Pereyaslav Articles: re-alliance with Russia

- 1660: Treaty of Chudnov: re-alliance with Poland

- 1667: Truce of Andrusovo: Ukraine divided along Dnieper; but Kiev to Russia, Zaporozhia a condominium; Cossacks not consulted; ends Russo-Polish War; to expire in 13 years

- 1672: Treaty of Buchach: During Polish–Ottoman War (1672–1676);Podolia to Turkey; right bank to Doroshenko as Turkish vassal; not implemented;

- 1676: Treaty of Żurawno: confirms 1672 but more favorable to Poland;ends Turkish war

- 1686: Treaty of Perpetual Peace (1686) confirms 1667; Zaporozhia to Russia

- 1699: Treaty of Karlowitz: Poland regains Podolia

Sources

- Orest Subtelny, 'Ukraine, A History',2000: This article is largely a summary of Chapter 9.

- The Ruin (from Ukraine), Encyclopædia Britannica

- Encyclopedia of Ukraine