Scythia

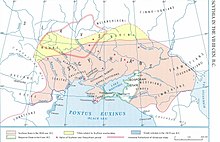

Scythia (UK: /ˈsɪðiə/, US: /ˈsɪθiə/;[2] from Greek: Σκυθική, romanized: Skythikē) was a region of Central Eurasia in classical antiquity, occupied by the Eastern Iranian Scythians,[1][3][4] encompassing Central Asia, parts of Eastern Europe east of the Vistula River with the eastern edges of the region vaguely defined by the Greeks. The Ancient Greeks gave the name Scythia (or Great Scythia) to all the lands north-east of Europe and the northern coast of the Black Sea.[5] During the Iron Age the region saw the flourishing of Scythian cultures.

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe

Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians

East Asia Europe East Asia Europe

Indo-Aryan Iranian

|

|

Religion and mythology

Indo-Aryan Iranian Others Europe

|

|

The Scythians – the Greeks' name for this initially nomadic people – inhabited Scythia from at least the 11th century BC to the 2nd century AD.[6] In the seventh century BC, the Scythians controlled large swaths of territory throughout Eurasia, from the Black Sea across Siberia to the borders of China.[7][8] Its location and extent varied over time, but it usually extended farther to the west and significantly farther to the east than is indicated on the map.[9] Some sources document that the Scythians were energetic but peaceful people.[10] Not much is known about them.

Scythia was a loose nomadic empire that originated as early as 8th century BC. The core of Scythians preferred a free-riding way of life.[11] No writing system that dates to the period has ever been attested, so majority of written information available today about the region and its inhabitants at the time stems from protohistorical writings of ancient civilizations which had connections to the region, primarily those of Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome and Ancient Persia. The most detailed western description is by Herodotus. He may not have travelled in Scythia and there is scholarly debate as to the accuracy of his knowledge, but modern archaeological finds have confirmed some of his ancient claims and he remains one of the most useful writers on ancient Scythia. He says the Scythians' own name for themselves was "Scoloti".[12]

Geography

The region known to classical authors as Scythia included:

- The Pontic–Caspian steppe: South-Eastern Ukraine, Southern Russia, Russian Volga, South-Ural regions and western Kazakhstan (inhabited by Scythians from at least the 8th century BC)[13]

- Genetic evidence for ranging clear across the plains (steppes) from Black Sea to Lake Baikal.[14]

- The Kazakh Steppe: northern Kazakhstan and the adjacent portions of Russia

- Sarmatia, corresponding to eastern Poland, Ukraine, southwestern Russia, and the northeastern Balkans,[15] ranging from the Vistula in the west to the mouth of the Danube, and eastward to the Volga

- Sakā Tigraxaudā ("the Sakas of the Pointed Caps"), corresponding to parts of Central Asia, including Kyrgyzstan, southeastern Kazakhstan, and the Tarim Basin

- Sistan or Sakastan, corresponding to southern Afghanistan, Sistan and Baluchestan Province of Iran, and Balochistan, Pakistan, extending from the Sistan Basin to the Indus River. Following successive invasions of the Indo-Greek kingdoms, the Indo-Scythians also expanded east, capturing territory in what is today the Punjab region.

- Parama Kamboja, corresponding to northern Afghanistan and parts of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan

- Alania, corresponding to the North Caucasus

- Scythia Minor, corresponding to the lower Danube river area west of the Black Sea, with a part in Romania and a part in Bulgaria

Maps

First Scythian kingdom

In the seventh century BCE, Scythians penetrated from the territories north of the Black Sea across the Caucasus. The early Scythian kingdoms were dominated by inter-ethnic forms of dependency based on subjugation of agricultural populations in eastern Transcaucasia, plunder and taxes (occasionally, as far as the region of Syria), regular tribute (Media), tribute disguised as gifts (Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt), and possibly also payments for military support (Neo-Assyrian Empire).

It is possible that the same dynasty ruled in Scythia during most of its history. The name of Koloksai, a legendary founder of a royal dynasty, is mentioned by Alcman in the seventh century BCE. Prototi and Madius, Scythian kings in the Near Eastern period of their history, and their successors in the north Pontic steppes belonged to the same dynasty. Herodotus lists five generations of a royal clan that probably reigned at the end of the seventh to sixth centuries BCE: prince Anacharsis, Saulius, Idanthyrsus, Gnurus, Lycus, and Spargapeithes.[16]

After being defeated and driven from the Near East, in the first half of the sixth century BCE, Scythians had to reconquer lands north of the Black Sea. In the second half of that century, Scythians succeeded in dominating the agricultural tribes of the forest steppe and placed them under tribute. As a result, their state was reconstructed with the appearance of the Second Scythian Kingdom which reached its zenith in the fourth century BCE. (see further: History of Xinjiang)

Second Scythian kingdom

Scythia's social development at the end of the 5th century BC and in the 4th century BC was linked to its privileged status of trade with Greeks, its efforts to control this trade, and the consequences partly stemming from these two. Aggressive external policy intensified exploitation of dependent populations and progressed the stratification among the nomadic rulers. Trading with Greeks also stimulated sedentarization processes.

The proximity of the Greek city-states on the Black Sea coast (Pontic Olbia, Cimmerian Bosporus, Chersonesos, Sindica, Tanais) was a powerful incentive for slavery in the Scythian society, but only in one direction: the sale of slaves to Greeks, instead of use in their economy. Accordingly, the trade became a stimulus for capture of slaves as war spoils in numerous wars.

Scythia from the late 5th to 3rd centuries BC

The Scythian state reached its greatest extent in the 4th century BC during the reign of Ateas. Isocrates[17] believed that Scythians, and also Thracians and Persians, were "the most able to power, and are the peoples with the greatest might". In the 4th century BC, under king Ateas, the tripartite structure of the state was eliminated, and the ruling power became more centralized. The later sources do not mention three basileuses any more. Strabo tells[18] that Ateas ruled over the majority of the North Pontic barbarians.

Written sources recount that before the 4th century BC the Scythian state expanded mainly to the west. In this respect Ateas continued the policy of his predecessors in the 5th century BC. During western expansion, Ateas fought the Triballi.[19] An area of Thrace was subjugated and levied with severe duties. During the 90-year life of Ateas (c. 429 BC – 339 BC) the Scythians settled firmly in Thrace and became an important factor in the politics of the Balkans. At the same time, both the nomadic and agricultural Scythian populations increased along the Dniester river. A war with the Bosporian Kingdom increased Scythian pressure on the Greek cities along the North Pontic littoral.

Materials from the site near Kamianka-Dniprovska, purportedly the capital of Ateas' state, show that metallurgists were free members of the society, even if burdened with imposed obligations. Metallurgy was the most advanced and the only distinct craft speciality among the Scythians. From the story of Polyaenus and Frontin, it follows that in the 4th century BC Scythia had a layer of dependent population, which consisted of impoverished Scythian nomads and local indigenous agricultural tribes, socially deprived, dependent and exploited, who did not participate in the wars, but were engaged in servile agriculture and cattle husbandry.

The year 339 BC proved a culminating year for the Second Scythian Kingdom, and the beginning of its decline. The war with Philip II of Macedon ended in a victory for Philip (the father of Alexander the Great). The Scythian king Ateas fell in battle well into his nineties.[20] Many royal kurgans (Chertomlyk, Kul-Oba, Aleksandropol, Krasnokut) date from after Ateas's time and previous traditions were continued; and life in the settlements of Western Scythia show that the state survived until the 250s BC. When in 331 BC Zopyrion, Alexander's viceroy in Thrace, "not wishing to sit idle", invaded Scythia and besieged Pontic Olbia, he suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of the Scythians and lost his life.[21]

The fall of the Second Scythian Kingdom came about in the second half of the 3rd century BC under the onslaught of Celts and Thracians from the west and of Sarmatians from the east. With their increased forces, the Sarmatians devastated significant parts of Scythia and, "annihilating the defeated, transformed a larger part of the country into a desert".[22]

The dependent forest-steppe tribes, subjected to exaction burdens, freed themselves at the first opportunity. The Dnieper and Southern Bug populace ruled by the Scythians did not become Scythians. They continued to live their original life, which was alien to Scythian ways. From the 3rd century BC for many centuries the histories of the steppe and forest-steppe zones of the North Pontic area diverged. The material cultures of the populations quickly lost their common features. And in the steppe, reflecting the end of nomad hegemony in Scythian society, the royal kurgans were no longer built. Archeologically, late Scythia appears first of all as a conglomerate of fortified and non-fortified settlements with abutting agricultural zones.

The development of Scythian society featured the following trends:

- The process of settlement intensified, as evidenced by the appearance of numerous kurgan burials in the steppe zone of the North Pontic-Caspian steppe. Some of them date to the end of the 5th century BC, but the majority belong to the 4th or 3rd centuries BC, reflecting the establishment of permanent pastoral coaching routes and a tendency to semi-nomadic pasturing. The Lower Dnieper area contained mostly unfortified settlements, while in Crimea and Western Scythia the agricultural population grew. The Dnieper settlements developed in what were previously nomadic winter villages, and in uninhabited lands.

- Social inequality increased, with the ascent of the nobility and further stratification among free Scythian nomads. The majority of royal kurgans date from the 4th century BC.

- The subjugation of the forest-steppe population increased, as traced in the archeological record. In the 4th century BC in the Dnieper forest-steppe zone, steppe-type burials appear. In addition to the nomadic advance in the north in search of the new pastures, they show an increase of pressure on the farmers of the forest-steppe belt. The Boryspil kurgans belong almost entirely to soldiers and sometimes even to women warriors. The heyday of steppe Scythia coincides with decline of the forest-steppe. From the second half of the 5th century BC, importing of antique goods to the Middle Dnieper decreased because of the pauperization of the dependent farmers. In the forest-steppe, kurgans of the 4th century BC are poorer than during previous times. At the same time, the cultural influence of the steppe nomads grew. The Senkov kurgans in the Kiev area, left by the local agricultural population, are low and contain poor female and empty male burials, in a striking contrast with the nearby Boryspil kurgans of the same era left by the Scythian conquerors.

- City life took root in Scythia.

- Trade with Northern Black Sea Greek cities grew, and increased the Hellenization of the Scythian aristocracy. After the defeat of Athens in the Peloponnesian war of 431 to 404 BC, Attican agriculture was ruined. Demosthenes wrote that Athens imported about 400,000 medimns (63,000 tons) of grain annually from the Bosporus. The Scythian nomadic aristocracy not only played a middleman role, but also actively participated in the trade in grain (produced by dependent farmers as well as slaves), skins and other goods.

Scythia's later history is mainly dominated by sedentary agrarian and city elements. As a result of the defeats suffered by Scythians, two separate states formed, the "Lesser Scythias": one in Thrace (Dobrudja), and the other in the Crimea and the Lower Dnieper area.[23]

Later Scythian kingdoms

Having settled this Scythia Minor in Thrace, the former Scythian nomads (or rather their nobility) abandoned their nomadic way of life, retaining their power over the agrarian population. This little polity should be distinguished from the Third Scythian Kingdom in Crimea and Lower Dnieper area, whose inhabitants likewise underwent a massive sedentarization. The interethnic dependence was replaced by developing forms of dependence within the society.

The enmity of the Third Scythian Kingdom, centred on Scythian Neapolis, towards the Greek settlements of the northern Black Sea steadily increased. The Scythian king apparently regarded the Greek colonies as unnecessary intermediaries in the wheat trade with mainland Greece. Besides, the settling cattlemen were attracted by the Greek agricultural belt in Southern Crimea. The later Scythia was both culturally and socio-economically far less advanced than its Greek neighbors such as Olvia or Chersonesos.

The continuity of the royal line is less clear in the Lesser Scythias of Crimea and Thrace than it had been previously. In the 2nd century BC, Olvia became a Scythian dependency. That event was marked in the city by minting of coins bearing the name of the Scythian king Skilurus. He was a son of a king and a father of a king, but the relation of his dynasty with the former dynasty is not known. Either Skilurus or his son and successor Palakus were buried in the mausoleum of Scythian Neapol that was used from c. 100 BC to c. 100 AD. However, the last burials are so poor that they do not seem to be royal, indicating a change in the dynasty or royal burials in another place.

Later, at the end of the 2nd century BC, Olvia was freed from Scythian domination, but became a subject to Mithridates I of Parthia. By the end of the 1st century BC, Olbia, rebuilt after its sack by the Getae, became a dependency of the Dacian barbarian kings, who minted their own coins in the city. Later from the 2nd century AD Olbia belonged to the Roman Empire. Scythia was the first state north of the Black Sea to collapse with the invasion of the Goths in the 2nd century AD (see Oium). At the end of the 2nd century AD, King Sauromates II critically defeated the Scythians and included the Crimea into his Kingdom of the Cimmerian Bosporus, a Roman client state.

Scythian kings

- Oricos (c. 500 BC) – was a Scythian king, the son of King Ariapeithes (or Ariapifa), the consanguinity brother of King Scylas.[16]

- Scylas (c. 500 BC) – Herodotus describes him as a Scythian whose mother was Greek, he was expelled by his people

- Octamasadas (c. 450 BC) – was put on the throne after Scylas

- Ateas (c. 429–339 BC) – defeated by the Macedonians; his empire fell apart

- Skilurus (c. 125–110 BC) – died during a war against Mithridates VI of Pontus

- Palacus (c. 100 BC) – the last Scythian ruler, defeated by Mithridates

Scythian tribes

Many different groupings of Scythian tribes include the following:

See also

- European Scythian campaign of Darius I

- Indo-Scythians

- Maeotian Swamp

- Sarmatia

- Scythian art

References

- Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (2014-11-14). "Scythian – ancient people". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 2017-03-27. Retrieved 8 May 2018.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (2014-04-16). "Scythian". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 2014-05-21. Retrieved 16 May 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

"Scythia (historical empire)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 11 September 2018.THIS IS A DIRECTORY PAGE. Britannica does not currently have an article on this topic.

- "Definition of 'Scythia' | Collins English Dictionary". www.collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2017-12-01. Retrieved 2017-12-01.

- "Scythia". Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- "The Scythians". history-world.org. Archived from the original on 2015-03-28.

- William Smith (ed.). "Scy´thia". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography (1854). Archived from the original on 2015-07-17.

- Thomas A. Lessman (2004). "World History Maps". Talessman's Atlas. Thomas Lessman. Archived from the original on 8 December 2013. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- Bell-Fialkoff, Andrew Villen, ed. (2000). The role of migration in the history of the Eurasian steppe : sedentary civilization vs. "barbarian" and nomad (1st ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 190. ISBN 0312212070. OCLC 909840823.

- Kennedy, Maev (2017-05-30). "British Museum to go more than skin deep with Scythian exhibition". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- Giovanni Boccaccio’s Famous Women translated by Virginia Brown 2001, p. 25; Cambridge and London, Harvard University Press; ISBN 0-674-01130-9 ".....extending from the Black Sea in a northerly direction towards Ocean." In Boccaccio's time the Baltic Sea was known also as Oceanus Sarmaticus.

- electricpulp.com. "SCYTHIANS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- "Great Empires of Central Asia, Part 3: Pirates on a Sea of Grass – The Strange Continent". The Strange Continent. 2017-10-28. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- Σκώλοτοι (Scōloti, Herodotus 4.6)

- Sinor, Denis (1990). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.

- Unterländer, 2017

- Harry Thurston Peck (1898). Harpers Dictionary of Classical Literature and Antiquities.

- Herodotus IV, 76

- Isocrates 436–338 BC, Panegyricus 67

- Strabo VII, 3, 18

- Polyaenus, Stratagems VII, 44, 1

- Trogus, Prologue, IX

- Justin, XII, 1, 4

- Diodorus, 11, 43, 7

- Strabo VII, 4, 5.

Further reading

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Scythia. |

- Ovid's poems Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto about his exile in Tomis contain some details of Scythia.

- Alekseev, A Yu.; Bokovenko, N.A.; Boltrik, Yu; Chugunov, K.A.; Cook, G.; Dergachev, V.A.; Kovalyukh, N.; Possnert, G.; van der Plicht, J.; Scott, E.M.; Semeetsov, A.; Skripkin, V.; Vasiliev, S.; Zaitseva, G. (2001), "Chronology of Eurasian Scythian Antiquities Born by New Archaeological and C14 Data", Radiocarbon, 43 (2B): 1085–1107, doi:10.1017/S0033822200041746

- Bunker, Emma C. (2002). Nomadic art of the eastern Eurasian steppes: the Eugene V. Thaw and other New York collections. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9780300096880.

- Khazanov, A.M. (1975), Золото скифов [Social history of Scythians] (in Russian)

- Karyshkovskij, Pyotr O. (1988), Монеты Ольвии, ISBN 5-12-000104-1

External links

- "Scythie : Une bibliographie introductive" [An Introductory Bibliography on Scythia], Bibliothèque des Sciences de l'Antiquité, Université Lille (in French)